Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is world’s most deadly pathogen. Unlike less virulent mycobacteria, Mtb produces 1-tuberculosinyladenosine (1-TbAd), an unusual terpene nucleoside of unknown function. Here we show that 1-TbAd is a naturally evolved phagolysosome disruptor. 1-TbAd is highly prevalent among patient-derived Mtb strains, where it is among the most abundant lipids produced. Synthesis of TbAd analogs and their testing in cells demonstrates that their biological action is dependent on lipid linkage to the 1-position of adenosine, which creates a strong conjugate base. Further, C20 lipid moieties confer passage through membranes. 1-TbAd selectively accumulates in acidic compartments, where it neutralizes pH and swells lysosomes, obliterating their multi-lamellar structure. During macrophage infection, a 1-TbAd biosynthesis gene (Rv3378c) confers marked phagosomal swelling and intraphagosomal inclusions, demonstrating an essential role in regulating the Mtb cellular microenvironment. Whereas macrophages kill intracellular bacteria through phagosome acidification, Mtb abundantly coats itself with antacid.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) kills more humans than any other pathogen1. Whereas most bacterial pathogens cause acute disease, Mtb usually undergoes a years-long infection cycle. Mtb persists in humans in part through parasitism of macrophage phagosomes. Survival in this intracellular niche is accomplished by limiting phagosomal maturation and intracellular killing mechanisms2–4, while offering partial cloaking from immune cells and access to lipids and other host nutrients5,6. Because Mtb interactions with the host play out over years and at diverse anatomical sites, pinpointing specific events that determine tuberculosis (TB) disease outcome is challenging. However, a successful approach has been the comparative profiling of mycobacteria of varying virulence to discover factors selectively present in highly virulent species. Mycobacterial species naturally differ in their potential to infect, persist, and cause TB disease and transmit among hosts. With an estimated 1.7 billion infections worldwide1, only Mtb has broadly colonized the human species, and humans represent its only natural host. These observations highlight the need to identify factors selectively expressed in Mtb but not in other mycobacterial species.

Comparative genomics and transcriptomics have isolated factors selectively present in Mtb, such as the ESX-1 transporter7. Whereas genetic techniques are widely used, comparative chemical biology screens are uncommon in mycobacteria. We developed a high-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS)-based lipidomics platform for analysis of all chloroform/methanol-extractable mycobacterial lipids 8,9. Comparative lipidomics of Mtb and BCG identified a previously unknown, Mtb-specific lipid missed by genomics approaches: 1-tuberculosinyladenosine (1-TbAd, 1)10. Cyclization of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate into tuberculosinyl pyrophosphate (TPP) occurs via the enzyme, Rv3377c, and tuberculosinyl transferase (Rv3378c) generates 1-TbAd, which can chemically rearrange to N6-TbAd (2)10–12. So far 1-TbAd has been detected only in Mtb12, so its expression correlates with evolved virulence. However, 1-TbAd has been studied only in laboratory-adapted strains12,13, and the extent to which it is produced by patient-derived Mtb strains remains unknown.

Further, 1-TbAd’s function remains unknown. Transposon inactivation of Rv3377c or Rv3378c reduced Mtb uptake, phagosomal acidification and killing of Mtb in mouse macrophages14. Therefore, 1-TbAd might influence some aspects of these processes in host cells. However, any host receptor, receptor-independent-mechanism, or other target of 1-TbAd in host cells remains unknown. Commonly used bioinformatic predictors were not helpful for understanding 1-TbAd function, as we could not identify orthologous biosynthetic genes or similar 1-linked purines in other species. Therefore, we tested diverse candidate mechanisms of 1-TbAd action on human cells. Unexpectedly, 1-TbAd acts as antacid that directly protects Mtb from acid pH and physically remodels Mtb phagolysosomes. Whereas Mtb was previously known to resist acidification via exclusion of lysosomal fusion with infected phagosomes,4,6,15, here we propose that Mtb also resists its normally acidic microenvironment by shedding massive quantities of antacid.

Results

High prevalence of 1-TbAd among clinical Mtb strains

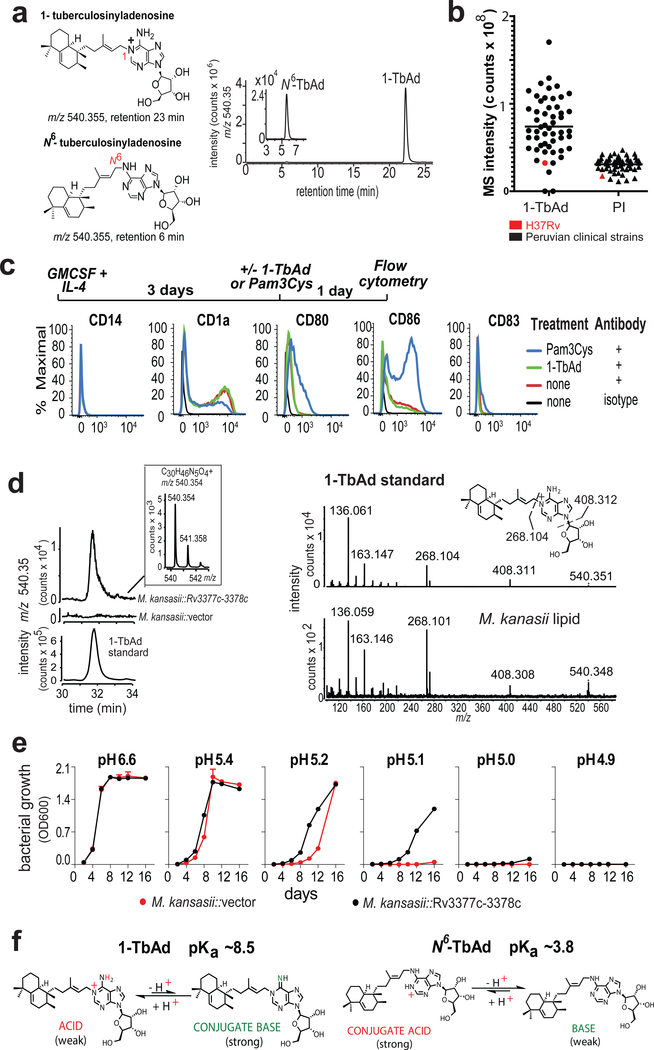

1-TbAd was identified in the laboratory strain H37Rv10–12. To determine if 1-TbAd is produced in patient-derived Mtb strains, we cultured 52 sputum isolates from Peruvian TB patients. Complex lipid extracts were subjected to positive mode HPLC-MS, where ion chromatograms matching the mass (m/z 540.4) and retention time values of 1-TbAd (23 min) and N6-TbAd (6 min) tracked key compounds (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Using phosphatidylinositol (3) (PI, m/z 870.6) as a loading control, we detected strong signals for 1-TbAd in 50 of 52 patient-derived Mtb strains (Fig. 1b), leading to several conclusions. 1-TbAd is highly prevalent (96%) but not universally present among strains. Among the 50 1-TbAd+ strains, mean 1-TbAd signals were higher than for PI, an abundant membrane lipid. Patient-derived strains expressed 1-TbAd at higher mean intensity (78×106) than strain H37Rv (31×106), indicating that prior studies on laboratory strains10,12 underestimated production by clinical strains.

Figure 1. Testing signaling-dependent and signaling independent effects of TbAd on human cells.

a) 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd were detected as HPLC-MS ion-chromatograms. b) Raw MS counts for 1-TbAd and phosphatidylinositol (PI) were measured in 52 clinical strains and the laboratory strain H37Rv. c) Human monocytes were treated with cytokines followed by a TLR2 agonist (Pam3Cys) or 1-TbAd and subjected to flow measurement of activation markers in 3 independent experiments showing similar results. d) The Rv3377c-Rv3378c locus was transferred into M. kansasii, conferring production of a molecule with equivalent mass, retention and CIDMS fragments found in 1-TbAd. e) M. kansasii was grown in liquid media at various pH values in duplicate with low variance (coefficient of variation < 2 % for all but one measurement) in three independent experiments. f) pKa’s are derived from measurements of dimethylallyladenosine and related compounds(21, 22), which indicate that 1-TbAd is predominantly charged but in equilibrium with its uncharged conjugate base at neutral pH. Thus, 1-TbAd but not N6-TbAd exists as a strong conjugate base.

Extending a prior study that detected 1-TbAd only in Mtb12, a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) analysis identified orthologs of Rv3377c and Rv3378c only in species highly related to Mtb. We were unable to identify species with orthologs among environmental mycobacteria distant from the Mtb complex or any other bacterium, including common non-mycobacterial lung pathogens (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Although these genetic results do not rule out convergent evolution of TbAd-like molecules based on unrelated genes, the likely conclusion is that TbAd biosynthesis is restricted to virulent mycobacterial species. Mtb-specific expression of TbAd biosynthesis genes and broad clinical prevalence of 1-TbAd provided a strong rationale to determine TbAd’s function.

TbAd biosynthetic genes in pH regulation

Macrophages are host cells for Mtb residence and play key roles in killing Mtb4. The known roles of adenosine and other purinergic receptors on macrophages and the adenosine moiety in TbAd16,17 led to testing of its activating properties on mixed human myeloid cells. However, 1-TbAd did not alter markers of monocytes (CD14), activation (CD80, CD86) or maturation (CD1a, CD83), which tested MyD88, MAP kinase and other activation pathways (Fig. 1c). We considered quorum sensing, but found no correlation 1-TbAd concentrations with growth. (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Based on the observed high 1-TbAd production (Fig. 1b) and reinterpretation of a transposon screen showing that Rv3377c and Rv3378c controlled Mtb phagosomal acidification14, we hypothesized that 1-TbAd might act as an exotoxin that controls the pH of phagolysosomes. This hypothesis was plausible because only Mtb blocks phagosomal acidification4, and only Mtb is known to produce 1-TbAd12 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Two landmark studies previously showed that Mtb blocks vesicular ATPase (vATPase) fusion with infected phagosomes. This deacidification mechanism is now considered a central means of evasion of cellular killing by macrophages2,3. Resetting pH from 5 to 6.2 inhibits downstream anti-bacterial effector functions15,18, including acid hydrolases, reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates4,19 as well as autophagy, which is a major cellular pathway controlling Mtb survival20.

In contrast to deacidification via vATPase exclusion2,3, two observations indicated that TbAd likely operated via a previously unknown mechanism. First, we transferred Rv3377c-Rv3378c into M. kansasii, which conferred biosynthesis of a molecule with the mass, retention time and collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectrum (Fig. 1d) of 1-TbAd. Gene transfer did not affect growth in media at neutral pH, but did increase survival under pH stress (Fig. 1e). Increased growth was observed at pH 5.4–5.1, which can be achieved in activated macrophages, but is not found during virulent Mtb infection, where pH is 6–6.26. Taken together, increased Mtb survival after knock-out of Rv3377c-Rv3378c14 and knock-in to M. kansasii provided strong links of TbAd biosynthetic genes with mycobacterial growth and survival. Importantly, the M. kansasii experiment indicated that TbAd biosynthetic genes act on Mtb itself, so key effects occurred independently of vATPases and all other host cell factors. A second clue to a possible function is that 1-TbAd is a strong conjugate base, so it has intrinsic antacid properties. Model compounds 21,22 indicate that the pKa of 1-TbAd is ~8.5. The lipid linkage to the 1-position of adenosine renders the molecule acidic and therefore in equilibrium with its conjugate base, which is a strong base. (Fig. 1f). Thus, the abundant shedding of 1-TbAd into the extrabacterial space10 could act as an antacid, locally neutralizing the acidic phagolysosomal microenvironment.

Massive biosynthesis of 1-TbAd by Mtb

Unlike receptor-mediated amplification, base-mediated pH neutralization is stoichiometric: one molecule of basic 1-TbAd captures one proton (Fig. 1f). De novo synthesis of 1-TbAd requires 26 steps (Supplementary Fig. 2), so neutralization of pH by ~0.7 pH units would be metabolically expensive. Mitigating this concern, Mtb strains showed high absolute MS signals (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and produce 1-TbAd constitutively under many conditions10,11 and at low and high bacterial density (Supplementary Fig. 1d). pH-dependent effector molecules in phagolysosomes are directly adjacent to intracellular mycobacteria, and phagosomes have a small volume (~10−15L) (23). Thus, effective pH neutralization could plausibly be generated in close proximity to Mtb.

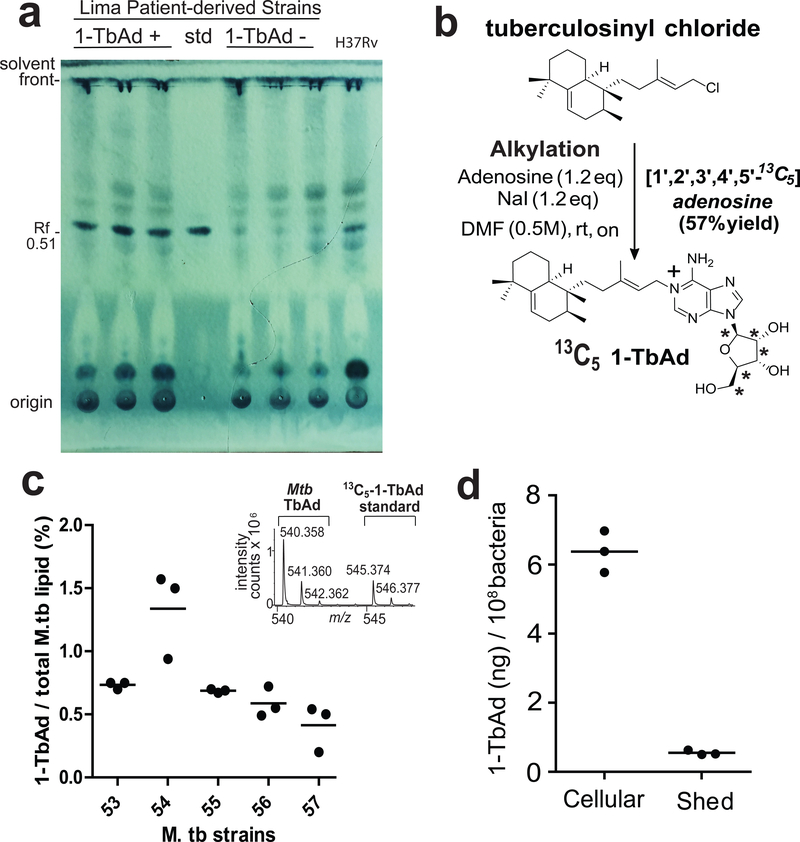

To assess if 1-TbAd biosynthesis was quantitatively sufficient for its proposed cellular effect, we measured 1-TbAd among additional patient-derived Mtb strains. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) of total lipids from three TbAd+ but not TbAd− strains showed dark spots with the same retention factor (Rf) as the 1-TbAd standard (0.51). This spot was among the darkest spots seen in total Mtb lipid extracts (Fig. 2a). After synthesis of [13C5]-1-TbAd (4) (m/z 545.374) as an internal standard (Fig. 2b) quantitative analysis demonstrated that 1-TbAd comprised ~1 percent of total Mtb lipids in clinical strains (Fig 2c). We measured ~7 ng 1-TbAd per 108 bacteria, with 91% cell-associated and 9% shed (Fig. 2d). Assuming one bacterium per phagosome23, intraphagosomal concentrations could plausibly reach micromolar concentrations and cause ~ 0.7 pH unit effect (Fig. S3)6,14. Overall, these experiments document massive biosynthesis and accumulation, establishing 1-TbAd as one of the most abundant Mtb lipids.

Figure 2. Quantitative measurements of 1-TbAd using an internal standard on a per cell basis.

a) Total lipids from three 1-TbAd+ and three 1-TbAd- strains were separated on normal phase silica TLC using chloroform/acetic acid/methanol/water mixtures in comparison to a 1-TbAd standard and a H37Rv lab strain. Lipids were subjected to charring after spraying with a phosphomolybdic acid solution. b) Labeled 1-TbAd was synthesized using 13C5 labeled adenosine whose mass spectral peaks did not overlap with those of natural 1-TbAd, allowing its use an in internal control. c) Total lipids from 5 patient-derived Mtb strains were weighed and subjected to HPLC-MS measurement in triplicate using the 13C-labeled internal standard to provide absolute mass values, which were expressed as the percentage of input lipid from 3 biologically independent samples.. d) For one representative clinical strain, lipids were extracted from the cell pellet (cellular) or conditioned media (shed) and measured as in c), expressed on a per cell basis based on colony forming unit (cfu) measurements from the input culture.

Influence on lysosomal pH in cells

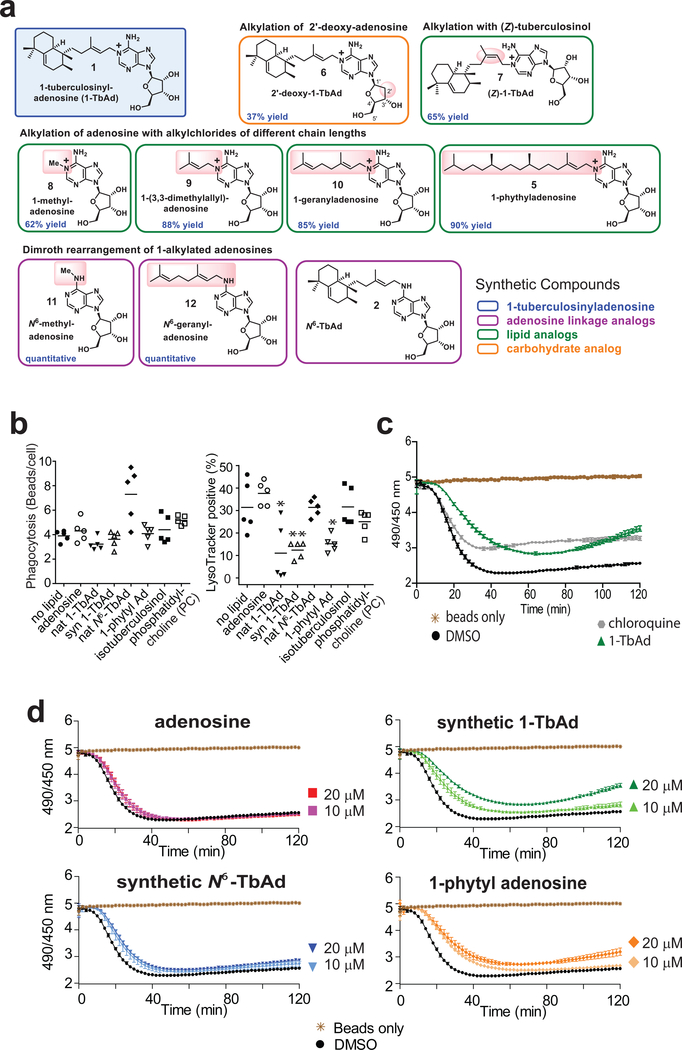

Next, we tested 1-TbAd’s effect on phagocytosis and lysosomal pH in macrophage-like (THP-1) cells. Because trace contaminants in Mtb-derived 1-TbAd can confound cellular assays, we synthesized 1-TbAd as well as nine analogs (compounds 5–12) for testing in parallel to Mtb-derived material24 (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4). Lysotracker is a red fluorescent dye that accumulates in acidic compartments. Pre-feeding cells with green fluorescent beads allows concomitant measurement of phagocytosis (Supplementary Fig. 5). Green beads were rarely seen outside the perimeter of cells in diffraction interference contrast (DIC) images and could be excluded when present, (Supplementary Figs. 5, left panels, 6a). To assess cellular entry, a pilot study showed that ~81% of beads were ringed with LAMP-1 staining and that 1-TbAd pre-treatment did not alter this ratio (Supplementary Fig. 6a). For the larger study with 7 tested compounds (Supplementary Fig. 5), fluorescence results from 5 fields (>100 cells) showed similar results in three assays (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Using total bead uptake as a measure of phagocytosis, we found no statistically significant changes in any condition. For measurement of lysotracker+ compartments, two negative controls, phosphatidylcholine (13) and isotuberculosinol (14), showed no effect. Both natural and synthetic 1-TbAd significantly reduced the number of lysotracker+ compartments (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 5, 6b). 1-phytyladenosine (5), which contains a straight chain polyprenyl group substituted for the ringed tuberculosinyl unit in 1-TbAd, showed a similar effect, indicating that the halimane core is not essential. Adenosine (15) and N6-TbAd, which lack the 1-linkage that confers proton capture (Figs. 1e, 3b), had no effect on lysotracker staining.

Figure 3. Effect of synthetic analogs of 1-TbAd on lysosomal pH in THP-1 cells and Macrophages.

a) Synthetic 1-TbAd and analogs that differ in the linkage or nature of the lipid or carbohydrate were prepared as described in Supplementary Fig. 4. b) Phagocytosis of green fluorescent beads and the pH-sensitive lysotracker dye in human THP-1 cells was monitored by confocal microscopy in three independent experiments,, each evaluating 5 low power sections with all outcomes shown in Supplementary Figs. 5–6. P values were calculated with the two-tailed Student’s T test and standard deviations are shown. c-d) Carboxyfluorescein beads were added to murine bone marrow-derived macrophages seeded in a 96-well plate, or to wells containing only media, and fluorescence was tracked with a microplate reader every 2 minutes for 2 hours. Compounds at indicated concentrations were added at the start of the assay. Data are shown as means with standard deviations from 5 or 6 replicate wells, which are representative of three independent experiments.

Extending this preliminary study of THP-1 cells, we next undertook studies of primary mouse bone marrow macrophages treated with carboxyfluorescein. The latter approach allows more direct assessment of pH through comparison of fluorescence at pHdependent (excitation 490 nm, emission 520 nm) and pH-independent (excitation 450 nm, emission 520 nm) wavelengths (25). Feeding carboxyfluorescein silica beads to fresh macrophages provides a readout of relative pH as phagosomes mature over time (26). 1-TbAd and chloroquine (16), a positive control for a lysosomotropic base, showed similar outcomes. Chloroquine provided a more rapid effect, but slightly lower peak effect on baseline fluorescence (Fig. 3c). Control wells with beads treated with 1-TbAd demonstrated the lack of direct effect on fluorescence (Fig. 3d). In wells with macrophages, addition of 1-TbAd and 1-phytyladenosine (5) delayed and reduced acidification of phagosomes in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas adenosine had little effect (Fig. 3d). Overall, in human and mouse cells, the outcomes of two pH assays matched the prediction that 1-linked but not N6-linked adenosines could raise pH. The role C20 lipid moieties was hypothesized to provide the hydrophobicity needed to traverse membranes. However, assays in live cells do not establish this conclusion because compounds could have been actively ingested.

Lysosomotropism predicts TbAd behavior

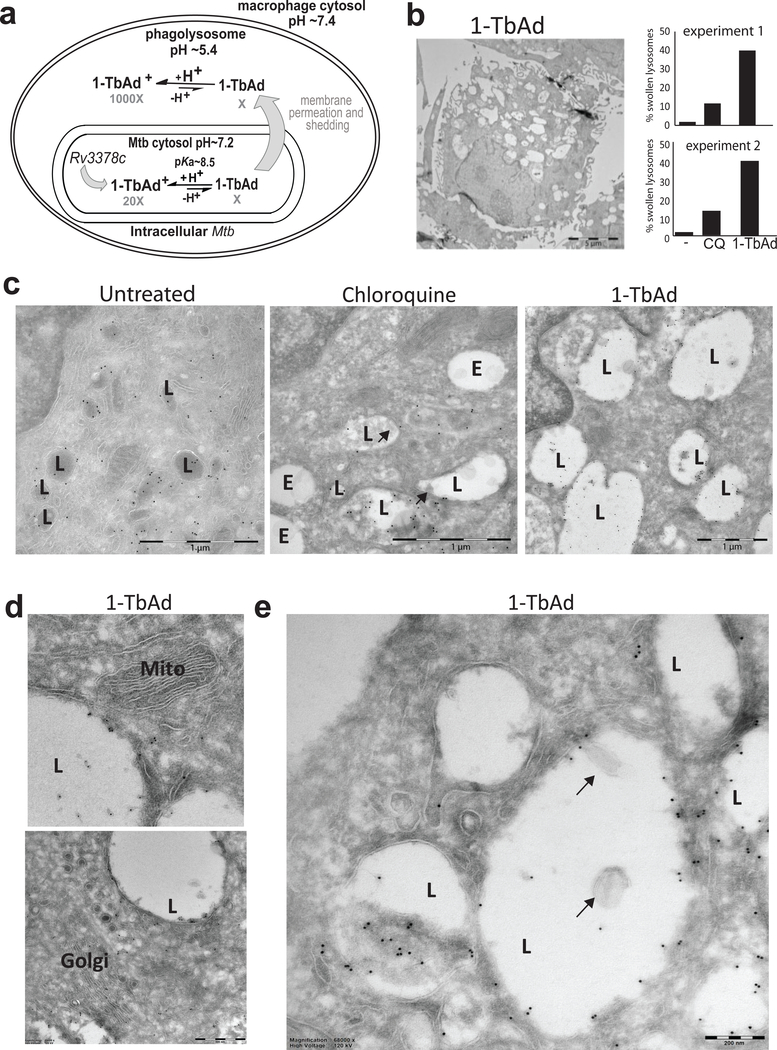

We combined these clear structure-activity relationships (SAR) with descriptions of lysosomotropic drug behavior by DeDuve27 to generate a detailed model for 1-TbAd function (Fig. 4a). 1-TbAd is in equilibrium with its uncharged conjugate base (Fig. 2e), which is proposed to permeate mycobacterial membranes to reach the phagosomes (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 7). In an acidic environment (pH 5.5–6.2), 1-TbAd (pKa ~8.5) but not N6-TbAd (pKa ~3.8) neutralizes pH, creating 1-TbAd+, a charged, membrane-impermeable species that is trapped (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Intraphagosomal protonation is predicted to generate a concentration gradient of uncharged base across the mycobacterial membrane, where permeation and trapping continue until equilibrium is reached. This process is proposed to create a large intraphagosomal pool of 1-TbAd+, whose relative size is predicted by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 7b). Whereas extracellular drugs, such as chloroquine, cross membranes into cells and enter lysosomes27, we propose the reverse topology: natural molecules made in the mycobacterial cytosol escape outwards and are trapped within maturing phagosomes (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

Figure 4. 1-TbAd is a lysosomotropic antacid.

a) Experiments test a compartmentalization model in which Rv3378c generates intrabacterial 1-TbAd, and the uncharged conjugate base permeates membranes. Low pH in phagolysosomes drives protonation, which incrementally raises pH and generates a charged species, 1-TbAd+, which cannot cross membranes.. b) Human macrophages generated with M-CSF and GM-CSF were treated for 2 hours with 1-TbAd (20 μM) or chloroquine (CQ) (20 μM) stained with anti-CD63 immunogold and assessed by transmission electron microscopy. An individual macrophage was counted as having swollen lysosomes when > 30 percent of cytosol was involved with CD63+ electron-lucent structures, as depicted in this low magnification image of a 1-TbAd treated cell. Images of > 150 cells were counted and subjected to the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test and adjusted by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (p=5.4×10−10 for control versus 1-TbAd and p=3.2×10−5 for chloroquine versus 1-TbAd). Actual sample sizes were n=54 or 48 for controls, n=45 or 48 1-TbAd-treated, and n=70 or 46 chloroquine-treated in trial one or two, respectively. c) High magnification images (bar, 1 μm) depict lysosomes (L), as defined by anti-CD63 staining at the limiting membrane, and endosomes (E), which are electron-lucent structures lacking anti-CD63 staining. Results are representative of three biologically independent experiments with similar outcomes. d) Mitochondria (Mito) and Golgi stacks (Golgi) are recognized by membrane arrangements, which unlike lysosomes, did not show swelling or increased electron lucency. e) Higher magnification (bar, 200 nm) images show inclusions in lysosomes that contain membranes (arrows) or non-membrane bound inclusions.

High-throughput screens28 and lysosomotropic models27 emphasize that a pKa ~8, as in the case of 1-TbAd, is optimal for lysosomotropism. Compounds with substantially higher pKa’s remain charged and impermeant, whereas those with lower pKa’s, like N6-TbAd, permeate membranes but do not efficiently capture protons. (Fig. Supplementary Fig. 5). These models led us to more extensively compare 1-TbAd function with chloroquine, a known lysosomotropic base27. Chloroquine is widely used against malaria, systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. These medical indications rely on its lack of signaling, low toxicity, and tropism to lysosomes29. In experimental medicine, chloroquine’s antacid effects block antigen presentation by MHC II, Toll-like receptor activation and autophagy29.

Electron microscopy of human macrophages

In electron microscopy (EM), macrophage lysosomes appear as highly electron-dense structures (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 8a-b). Chloroquine or 1-TbAd transformed these small, electron-dense compartments into large, electron-lucent compartments that, despite complete loss of their multi-lamellar and electron-dense appearance, could still be recognized as lysosomes based on immunogold staining of CD63, a lysosome marker (Fig. 4b–c, Supplementary Fig. 8). This process was widespread (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Figs. 8a,c,e), such that we designated cells as having swollen lysosomes when the electron-lucent compartments involve more than one-third of the cytoplasm (Figs. 4b). Both the nature of intraphagosomal inclusions and the broad extent of cellular involvement is visualized through side by side comparison of low and high magnification images with pseudo-coloring of lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 8). Analysis of > 100 cells per condition, 1-TbAd showed statistically significant effects on lysosomes compared to no treatment (Fig. 4b).

For chloroquine this structural transformation is known to involve accumulation in acidic compartments and secondary osmotic effects 20,27,29. 1-TbAd showed stronger effects than chloroquine on human macrophages (Fig. 4b). The lysosomotropic model predicts that non-acidic organelles, such as early endosomes, Golgi bodies and mitochondria, would be relatively unaffected27, as observed in our assays (Fig. 4d). For chloroquine and 1-TbAd we noted the appearance of small, mildly electron dense inclusions, including membrane-containing intralysosomal bodies (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 8), which for chloroquine, results from autophagy blockade20,27,29. Last, a negative control, tuberculosinol (17), produced no discernable effects on lysosomes, again suggesting the importance of the 1-adenosine linkage (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Testing vesicle permeation

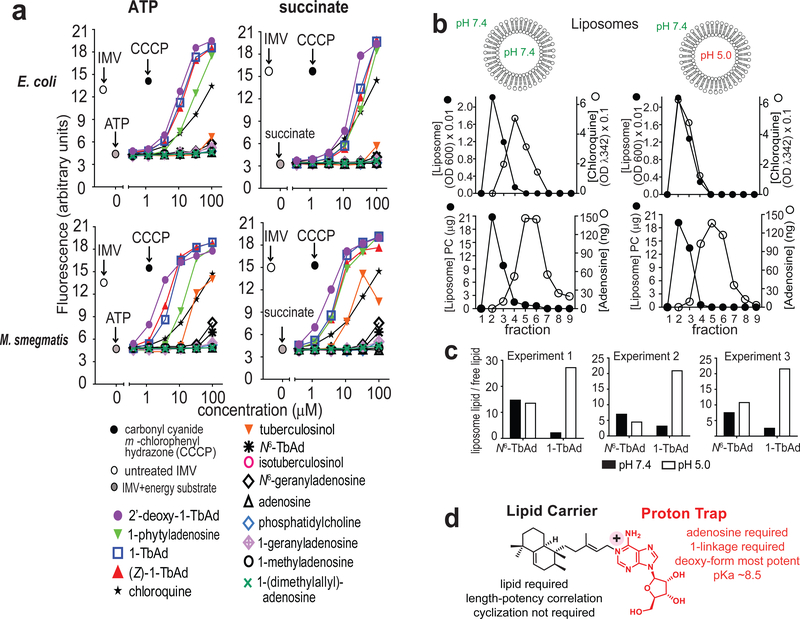

Lysosomotropism requires membrane permeation (Fig. 4a), but lysotracker suppression in THP-1 cells (Fig. 3b) and macrophages (Fig. 3d) might have occurred through active cellular uptake. To measure transmembrane diffusion, we turned to model membrane systems. For inverted membrane vesicles (IMVs)30, inversion orients proton pumps so that the interior spontaneously acidifies in response to added energy substrates, ATP or succinate. The reporter, 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxy acridine (AMCA), is quenched by acid. Quenching is reversed by penetration of lysosomotropic substances into the IMV. Compounds that disrupt membranes cause decreased fluorescence, providing a control for membrane leakage30. Unlike cells (Figs. 3, 4, Supplementary Fig. 5), IMVs have no active cytoskeleton-mediated drug uptake. As a positive control, chloroquine showed reporter quenching with half maximal effect at ~20 μM, matching its expected function and potency27–29 (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5. Transmembrane permeation by TbAd analogs.

a) Fluorescence spectroscopy assays of E. coli and M. smegmatis (M. smeg) inverted membrane vesicles (IMVs) used ATP or succinate to generate a pH gradient, followed by addition of the indicated compound. Four representative assays are shown from a total of 6 assays that found similar results and which were conducted in a blinded fashion. b-c) Liposomes with a neutral or acidic interior were treated with negative control compounds (adenosine, N6-TbAd), a positive control (chloroquine), or 1-TbAd, then subjected to size exclusion chromatography. Liposomes (black) were measured using absorbance at 600 nm, and chloroquine was measured at 342 nm. Adenosine-containing compounds were measured using MS. 1-TbAd at pH 5.0 differed significantly from all other treatments (p < 0.01) by least-squares means post test with adjustment by Tukey’s method after fitting a linear model and factorial ANOVA. d) Summary of cellular, IMV and liposome-based analysis of TbAd analogs identifies separate roles on the lipid carrier and proton trap site at the 1-position of adenosine.

All four 1-linked adenosines (1, 5–7) carrying C20 lipids were more potent than chloroquine, and none of the N6-linked adenosines (2, 11, 12) showed suppression (Fig. 5a). These results suggest direct membrane permeation and rule in the 1-linkage as the essential chemical feature (Fig. 4a). Stereochemical changes in the 1-linked lipid ((Z)1-TbAd) (7), or an acyclic lipid (1-phytyladenosine, 5), had little effect, as long as a C20 lipid was present. However, C10, C5 or C1 lipid analogs (8–10) showed that potency declines as chain length decreases, consistent with the lipid moiety generating a hydrophobic effect (Figs. 3a, 5a). Carbohydrate-modified, 2’-deoxy-1-TbAd (6), was more potent than 1-TbAd and chloroquine. Thus, hydrophobicity and potency are correlated among analogs. This result suggests that hydrophobicity drives biological action and provides an approach to future synthesis of yet more potent compounds.. Similar results were observed when using ATP or succinate as energy substrates, and using M. smegmatis or E. coli IMVs (Fig. 5a). The SAR in IMVs generally matched the patterns seen in human (Figs. 3a, 4) and mouse cells (Fig. 3c–d).

Prior studies suggested that beads coated with the free alcohol component of TbAd could alter the pH of phagosomes31. However, isotuberculosinol (14) and tuberculosinol (17) are not predicted to have basic properties, and they showed few effects in lysotracker studies (Fig. 3b), EM images (Fig. S9) and E. coli IMVs (Fig. 5a). However, IMV assays with M. smegmatis membranes (Fig. 5a) did show some effect with synthetic tuberculosinol. These somewhat differing results might be explained if the tuberculosinyl moiety mediates some unknown but specific interaction with mycobacterial membranes.

Protein-free model membranes

To exclude artifacts from inhibitors binding to protein targets in IMVs, testing of protein-free membranes was required. Therefore, we generated liposomes with differing interior pH values (5.0 and 7.4) (Fig. 5b). Lysosomotropism predicts that externally applied compounds selectively penetrate acidic but not neutral liposomes. Fulfilling this prediction, chloroquine co-migrated with acidic but not neutral liposomes on a size-exclusion column. A negative control, adenosine, failed to bind to either liposome type. 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd showed some adhesion to neutral and acidic liposomes (Fig. 5b), which was likely mediated by their identical lipid moieties (Fig. 1a). Only 1-TbAd was preferentially captured by liposomes with an acidic interior (Fig. 5c). This reductionist system rules in a purely chemical mechanism: 1-TbAd is a membrane permeable antacid, where the 1-linked lipid moiety provides intrinsic transmembrane tropism for acidic compartments (Fig. 5d). Overall, 1-TbAd is a naturally evolved phagolysosome disrupter, whose action mimics the widely used lysosomotropic drug chloroquine.

Generation of Mtb lacking Rv3378c and 1-TbAd

To identify non-redundant functions of the 1-TbAd biosynthesis pathway during cellular infection, we deleted the tuberculosinyl transferase gene, Rv3378c, in the H37Rv strain (MtbΔRv3378c) (Supplementary Fig. 10a). We confirmed gene deletion and replacement with the hygromycin resistance cassette through polymerase chain reaction analysis, as well as the complete abrogation 1-TbAd biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. 10b). For genetic complementation (MtbΔRv3378c::Rv3378c), we used a single copy chromosomal integration of Rv3378c under control of a mycobacterial optimized promoter. We observed full restoration of 1-TbAd production to wild type levels after subculture and selection of a high producing Mtb clone (Supplementary Fig. 10b).

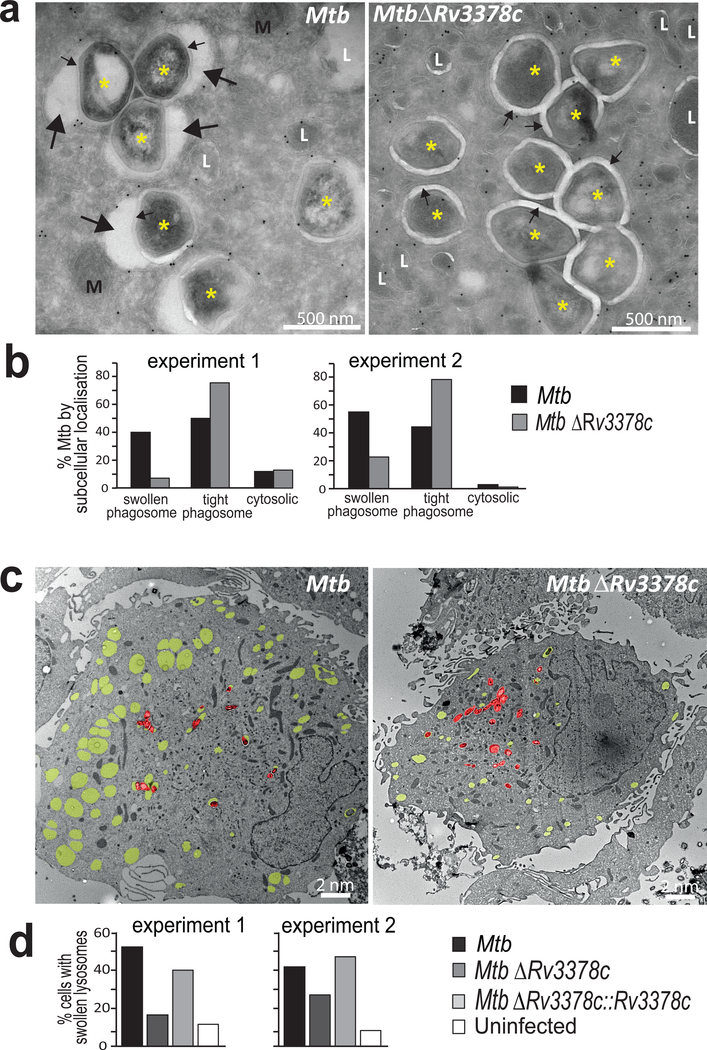

Role of biosynthetic genes in live macrophage infection

After 4 days of infection, human macrophages were examined by transmission EM. High magnification images depicting trans-bacterial sections revealed infected phagosomes. Tranverse sections show that mycobacterial cytosol (*) is surrounded by the cell wall, phagosomal space, limiting phagosomal membrane and macrophage cytosol (Fig. 6a). For MtbΔRv3378c, most intraphagosomal bacteria were surrounded by an electronlucent ring of uniform thickness (~20 nm), the mycobacterial polysaccharide capsule (Fig. 6a, small arrows)32. For MtbΔRv3378c the phagosomal membrane is typically tightly wrapped around the 20 nm mycobacterial capsule (tight phagosome).

Figure 6. Infection of human macrophages for 4 days with Mtb or the Rv3378c-deletion mutant, which lacks TbAd production.

a) High magnification images of macrophage cytosol containing Mtb (*), mitochondria (M), lysosomes (L), capsular layer (small arrow) or intraphagosomal area with inclusions (large arrow). b) Greater than 150 intracellular Mtb were evaluated at high power for their localization in the cytosol, tight phagosomes (small arrows) or large phagosomes (p=7.0×10−15 for swollen versus tight phagosomes). c) Low magnification images show yellow pseudocoloring for swollen lysosomes (CD63 immunogold, electron lucent) and red pseudocoloring highlights individual Mtb bacilli. d) Greater than 150 cells were evaluated as having swollen lysosomes when one-third of the cytosolic area showed electron-lucent CD63+ compartments (p < 0.001 for Mtb versus MtbΔRv3378c; p < 0.05 for MtbΔRv3378c versus MtbΔRv3378c::Rv3378c). All p values in b and d were calculated with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with independent experiments treated as strata and were adjusted using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg.

In contrast, for wild-type Mtb, phagosomal membranes typically showed numerous large (~20–250 nm) ectopic blebs (Fig. 6a, large arrows) outside the capsular ring. I n some cases these blebs nearly surround the bacterium, creating the appearance of a loosely wrapped (swollen) phagosome with many non-bacterial, intraphagosomal inclusions. Inspection of >150 phagosomes in each of two experiments showed that Rv3378c expression resulted in a 4.5-or 4.9-fold increase in the ratio of swollen to tight phagosomes(Fig. 6b). The swollen phagosomes provided clear evidence for compartment autonomous effects of Rv3378c expression (Fig. 4a). Low power analysis revealed expression of Rv3378c was associated with many swollen phagosomes that lacked visible bacteria (Fig. 6c). The broader involvement of compartments was somewhat surprising, because it suggested that 1-TbAd produced in one compartment could more broadly affect lysosomes in cells.

Therefore, we undertook more detailed and quantitative analysis of low magnification images of infected cells with visible bacteria (Fig. 6c, red pseudocolor). Individual cells were scored as having swollen lysosomes when one-third of the cytosol was involved (Fig. 6c, yellow pseudocolor). Compared to uninfected macrophages, Mtb-infected human macrophages showed marked increases with swollen lysosomes (Fig. 6d). Rv3378c deletion significantly reduced swelling, and complementation restored the phenotype to the baseline value. Although we cannot rule out undetected bacteria in swollen lysosomes, the multiplicity of infection used (2 bacteria/cell) and the large number of swollen compartments suggested non-compartment autonomous effects. We conclude that effects downstream of Rv3378c play an essential role in the physical remodeling of the local intraphagosomal growth niche of Mtb. Phenotypes from wild-type Mtb (Fig. 6) mimicked key aspects seen after treatment with pure 1-TbAd (Fig. 4c–e), and they match the predicted effects of release of any lysosomotropic substance27 and the known effects of chloroquine29.

Discussion

Based on 1-TbAd’s shed nature and restriction to virulent mycobacteria in the Mtb complex, we initially considered comparisons to bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins, like lipopolysaccharide, which mediates rapid and extreme host cellular response. Although no experiment can rule out receptor-mediated signaling, we found no evidence for generalized cellular activation in response to 1-TbAd. Mechanistically, increased growth of 1-TbAd+ M. kansasii at acidic pH is critical, because it rules in macrophageindependent effects on mycobacterial growth and specifically connects survival to pH. Rather than a generalized cellular toxin, 1-TbAd is a lysosomotrope, causing gross phagosome disruption and raising pH in THP-1 cells and macrophages. This conclusion is strengthened by comparison to the known lysosomotrope, chloroquine27,29, as well as consistent patterns among TbAd analogs that directly implicate the 1-linkage, which confers its antacid property.

Thus, 1-TbAd mediates a previously unknown effect involving neutralization and local remodeling of Mtb’s intracellular acidic growth niche within macrophages. Because 1-TbAd is initially released only at the surface of live mycobacteria, the model predicts the strongest effects within infected phagolysosomes. Therefore, finding broadly swollen lysosomes, including many compartments with no detectable bacilli was initially surprising. However, the reverse lysosomotropic model allows that steady production over time by intracellular bacteria could lead to 1-TbAd penetration to all acidic compartments, a hypothesis that can now be tested with kinetic studies.

Massive production of 1-TbAd, among 96% of tested patient strains is notable. Extending work in which TbAds were detected in mice12, these findings support the feasibility of developing 1-TbAd as a marker of TB disease. Also, the high production among patient strains highlights one surprising aspect of this work12, which is the failure of such an abundant molecule to be detected during decades of TB research. Overall, the high biosynthesis is well matched to an unamplified, stoichiometric mechanism of action that involves proton capture.

Modified adenosines and related purines have evolved repeatedly in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells, but 1-linked adenosines are rare in nature10,33. 1-linked adenosines can non-enzymatically rearrange to N6-variants 12, which occurs in vivo during infection in mice11. The instability of 1-linked purines might account for their rarity in nature, but they are stable in acid environments, as in the mechanism proposed here. SAR studies with synthetic analogs directly demonstrate that the 1-linkage, the unusual and defining chemical feature of 1-TbAd, controls its biological activity. Thus, the revised model is that among the last two steps of the natural TbAd biosynthetic pathway, 1-TbAd is the active metabolite that controls lysosomal function. N6-TbAd largely lacks this function, but might have utility as a species-specific diagnostic marker of infection.

Phagolysosomal acidification is a key outcome of the γ-interferon mediated interactions between macrophages and T cells. The role of acidification as an upstream controller of phagolysosome maturation and intracellular killing has been recognized for decades4,15, as has evidence for Mtb’s manipulation of this pathway2,3. Acidification blockade by Mtb is currently considered an immunoevasion mechanism resulting from bacterial blockade of vATPase delivery to infected phagosomes6. Whereas the previously known mechanism limits proton pumping into infected compartments, we propose that antacid-release is a complementary mechanism that acts within phagosomes to scavenge protons that do arrive.

Lysosomal acidification controls the final mechanisms of intercellular lipid and protein degradation that are common to autophagy pathways. Autophagic degradation is co-opted during Mtb infection to generate intracellular inclusions29,34, and chloroquine is perhaps the most widely used autophagy inhibitor in experimental settings29. Here we outline similar pKa’s, potency and biological function of 1-TbAd and chloroquine, pointing to a candidate role of 1-TbAd in autophagy inhibition. These observations support future development of synthetic 1-TbAd and analogs as lysosome disrupting drugs. Related to this, both chloroquine and Mtb acid blockade limits MHC class II peptide loading29, so 1-TbAd now becomes a candidate to influence MHC II mediated human T cell response.

Selective expression of 1-TbAd by Mtb, but not less virulent species, provides a correlative basis for proposing that 1-TbAd could be an evolved virulence factor. The Rv3377c-Rv3378c pathway is known only in an obligate human pathogen that continually grows under host immune pressure. Escape from acid mediated killing could plausibly outweigh the metabolic costs of 1-TbAd biosynthesis. This hypothesis is supported by experimental data: transposon deletion of either Rv3377c or Rv3378c diminishes Mtb survival in mouse macrophages14, and knock-in of these two genes confers a growth advantage in M. kansasii. Thus, these biological studies are consistent with the conclusion that the pH-neutralization mechanism identified here controls some aspect of Mtb growth and survival. The overarching questions going forward will be the extent to which this acid-neutralization mechanism controls Mtb outcomes during natural infection in vivo, and whether it acts in the distinct phases of acute infection, persistence or transmission.

Methods

Patient derived Mtb strains.

Mtb strains were cultivated from the sputum of human TB patients recruited in or near Lima Peru by Socios en Salud under oversight from the Institutional Committee of Ethics in Research (CIEI) of the Peruvian Institutes of Health, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Harvard Faculty of Medicine, and the Partners Healthcare IRB. Peruvian patients provided oral and written informed consent in Spanish.

Flow cytometry of human myeloid cells.

Monocyte-derived DCs were prepared by plating human monocytes in a 24-well plate (1 × 106) with 30 ng/mL of GM-CSF (Peprotech 300–03) and 40 ng/mL of IL-4 (200–04; Peprotech) for 3 days. The cells were then treated with either synthetic 1-TbAd, natural 1-TbAd, Pam3Cys-SKKKK (L2000, EMC Microcollections), or media for another day. Cells were then washed and collected for FACS analysis. For cell surface protein detection, cells were stained with mouse antihuman CD1a (OKT6; in-house purified); CD80 (557223), CD86 (555655), CD14 (550376; BD Pharmingen), and isotype controls for IgG1 (P3; in-house purified) or IgG2a (14–4724-B1, eBioscience) followed by a FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab’)2 (A-10683, ThermoFisher Scientific), then measured by a FACS Canto Flow Cytometer (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo.

Acidification and phagocytosis.

THP-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, Lglutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, β-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM HEPES. Green fluorescent beads (silica, 3 μM, excitation/emission: 485/510 nm, Kisker Biotech). The beads were washed 5 times with PBS and stored in 0.5% BSA in PBS (108 beads/mL) at 4 °C. Beads were then resuspended in complete media plus 10% human serum (Gemini) for 10 min before the phagocytosis assay. To generate macrophage-like cells, THP-1 cells were plated on cover slips in 24-well plates (3 × 105) and treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, p1585; Sigma-Aldrich), 50 nM, for 72 hours. The differentiated cells were washed twice, then rested in fresh media for 4 hours, followed by lipid treatment for 2 hours. Lipid samples were vortexed and sonicated for 2 minutes before being added to the cells. Cells were then fed with excess fluorescent beads (4 beads/cell) and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 1 min before incubation at 37 ˚C. After 30 min, cells were washed with PBS three times to remove extracellular beads, then treated with 250 nM Lysotracker-red DND-99 (L7528, ThermoFisher Scientific) at 37˚C for 60 min. To assess washing and surface adherence, pilot studies showed that beads were rarely found outside the margin of cells (< 2 %) and more that 80 percent of beads penetrated to LAMP-1+ compartments. Cells were washed, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min before the cover slips were mounted on the slides. Slides were analyzed on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-UC1 confocal microscope by counting 5 low power fields (~200 cells).

pH measurement in mouse macrophages.

To generate carboxyfluorescein beads for analysis of phagosomal pH, 50 μg of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen, CA) was added to 12.5 mg of carboxylated, 3 μm silica beads (Kisker Biotech, Germany) that had been covalently linked to human IgG (Sigma, MO) and defatted BSA26. After incubation on a neutator for 90 minutes at room temperature, the carboxyfluorescein beads were washed and stored in PBS at 4°C. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated from C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, ME), and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Gibco, CA), 15% L-cell conditioned media, 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, MO), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco, CA) and antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin) (Gibco, CA), at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. 2 × 105 macrophages/well were seeded into 96-well clear bottom black plates for assays (Corning Costar, NY). Assays were performed one-two days after seeding in the 96-well plates. Macrophages were washed 3 times with assay buffer (PBS, pH 7.2, 5% FBS, 5 mM dextrose, 1 mM CaCl2, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2), and assay buffer containing indicated concentrations of compounds, whose identities were blinded to the experimentalist, added back to each well as appropriate. Carboxyfluorescein beads at ~2–5 beads/macrophage in assay buffer containing compounds were then added, and bottom reads at 450 nm/520 nm and 490 nm/520 nm acquired every 2 minutes for 2 hours on a Biotek Synergy H1 microplate reader. A total of 5–6 replicate wells/condition were used, with temperature maintained at 37°C. The ratio of the carboxyfluorescein fluorescence signal at excitation 490 nm (pHsensitive) versus 450 nm (pH-insensitive) provides a readout of relative pH26. Animal procedures adhered to the NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”, with animal protocol (#B2016–37) approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tufts University in accordance with Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, US Department of Agriculture, and US Public Health Service guidelines.

Electron microscopy.

For EM studies, human monocytes (5 × 106) were treated with MCSF (25 ng/ml) and GM-CSF (2.5 ng/ml) for 6 days and treated with lipids or infected with Mtb. The infected cells were incubated 4h and washed to remove extracellular bacteria. The cells were incubated for 4 days and fixed with 2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.4M PHEM buffer (240mM PIPES, 100mM HEPES, 40mM EGTA, 8mM MgCl2). For the lipid treatment experiments, the cells were treated for 2h with 20uM lipid and the fixed cells were processed for EM as published35. For infection experiments, infected cells were incubated 4h and washed to remove extracellular bacteria. The cells were incubated for 4 days and fixed with 2% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.4M PHEM buffer (240mM PIPES, 100mM HEPES, 40mM EGTA, 8mM MgCl235. For EM, samples were embedded in gelatin blocks and plunge frozen in liquid nitrogen, and 60 nm ultrathin sections were produced at −120 °C. Then immunogold labeling was performed using antibodies against CD63 (Sanquin), CD107A (Biolegend), EEA1 (Thermo Scientific), rabbit anti mouse bridging antibody and 10 nm gold particles conjugated to protein A (Utrecht University). Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and were analyzed in a blinded manner using TEM (FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit Biotwin) at 100 kV.

Genomic analysis and statistics.

To discover possible orthologs, sequences of Rv3377c or Rv3378c from the NCBI Mtb H37Rv reference genome (NC_000962.3) were used to interrogate whole-genome sequences with the basic local alignment search tool (blastn) set at these parameters: base match score of 2, base mismatch score of −3, Evalue threshold of 10, minimum word size of 11, gap penalty of 5, and gap extension penalty of 2.

Liposome assays.

Phosphatidylcholine (Sigma P5394, 1.8 μmol) and cholesterol (C8667; Sigma, 0.73 μmol) were mixed in chloroform in a 50 mL glass tube. The solvent was evaporated under nitrogen to yield a thin film, which was then hydrated in citrate buffer (500 μL) with the desired pH (5.0 or 7.4) by vortexing, followed by 6 freeze-thaw cycles. Vesicle size was homogenized by using a liposome extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) through polycarbonate membranes (0.2 μM and 0.1 μM). Liposomes were dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4, 1 liter) overnight using a Slide-A-Lyzer MINI Dialysis Device with a 10 kDa cutoff value (100 μL device, Thermo Scientific). After dialysis, two batches of liposomes were adjusted to equal concentration (OD = 0.25 at 600 nm). The final liposomes were examined by TecnaiG2 Spirit BioTWIN electron microscopy at the Harvard Medical School Core EM Facility. Liposomes (25 μL) and chloroquine (Sigma C662825, 50 μM PBS solution) were mixed in a small glass insert, placed in an Eppendorf tube and incubated in a Thermomixer at 37 °C. After 2 hours, the mixtures were loaded onto a MicroSpin G-50 column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with PBS and nine 100 μL fractions were collected. The amount of liposomes in each fraction was determined by optical density. The liposomes were dispersed with 3 μL of Triton X-100 (10%) and the amount of chloroquine in each fraction was measured by the absorption at 342 nm. For adenosine (Sigma A9251) uptake, 25 μL of a PBS solution was mixed with 25 μL of liposomes, as described above except the final quantification steps. The collected fractions (100 μL each) were mixed with 0.5 mL of chloroform/methanol (1:2 v/v), vortexed, and dried under nitrogen. Each dried fraction was re-dissolved in a mobile phase of hexane/isopropyl alcohol (70:30 v:v) and loaded to a 1200 series HPLC system using a normal phase column (Varian MonoChrom Diol: 3 μm x 150 mm x 2 mm) and analyzed by using an Agilent 6520 Accurate Mass Q-Tof mass spectrometer, based on published methods (8). PC (m/z 760.58, used as a surrogate for liposome content) and adenosine (m/z 268.10) were quantified by comparing the peak area of extracted-ion chromatograms with external standards. For 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd uptake, the experiment was performed in triplicate. 1 μg of lipid sonicate (25 μL) was mixed with 25 μL of liposomes and incubated at 37 °C. After 2 h, the mixtures were loaded onto a MicroSpin G-50 column. Due to lipid adherence to the liposomes, the eluate consisted of two fractions: a liposome-associated lipid fraction (lipids co-elute with liposomes) and a liposome free lipid fraction (lipids that stay on the column). The PBS eluate (500 μL) and column contents (Sephadex G-50) were treated with chloroform/methanol (1:2) 2 mL and 0.5 mL, respectively. The PBS eluate and the column extracts were analyzed by LCMS-QToF as described above. Both 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd were detected as m/z 540.35, at retention times of 23 and 5 minutes, respectively.

IMV assays.

Synthetic TbAd-like compounds were tested in triplicate in a blinded fashion in four types of IMV assays using succinate or ATP as energy substrates and E. coli or M. smegmatis membranes in two independent experiments as described previously (16).

Knock-in of genes to M. kansasii.

M. kansasii ATCC 12478 was transformed with an integrative vector (pMV306) that either carried no insert (empty vector; EV), or a 2.4-kb PCR fragment containing Rv3377–8c under the control of a constitutive hsp60 promoter (Rv3377-Rv3378c). Cell-associated lipids were extracted and subjected to mass spectrometry analyses (10). To measure M. kansasii survival at different pH, organisims were maintained at mid-log phase (OD600 0.2–0.5), passed through 22-G and 25-G needles, centrifuged at 450 x g/5min to remove clumps, and resuspended in 20 ml media with altered pH (prepared using 2M HCl) at a theoretical OD600 0.01. Cultures were grown for 16 days in biological triplicates. At each time point, a volume of 100 μl was taken in duplicate from each culture to measure the OD600 on a 96-well tissueculture plate (Falcon) using the Infinite M200 Pro NanoQuant spectrophotometer (Tecan).

Deletion and complementation of Rv3378c.

Mtb strain H37Rv was used for complete deletion of Rv3378c using recombineering gene-replacement strategy36. A targeting construct consisting of 500bp flanking regions of Rv3378c and loxP-hygromycin-LoxP cassette was synthesized and cloned into a pUC57 vector. The linear DNA substrate was amplified from the vector, and electrophoretically transformed into the Mtb H37Rv strain carrying the pNit-recET-SacB-kan plasmid and induced to express recombinase. Transformed bacteria were plated on to 7H10 agar plates containing 50ug/ml hygromycin for selection of recombinants. The recombinants were further selected for absence of pNit-recET-SacB-kan plasmid by growing the colonies on 7H10 plates containing 5% sucrose and hygromycin (50 μg/mL) and subsequently testing the colonies for absence of growth on 7H10 plates with kanamycin (25 μg/mL). The recombinant colonies were screened by PCR for target gene deletion and replacement by hygromycin cassette. The PCR screening was performed using primers that amplify 5-prime junction, 3-prime junction. The entire target gene locus for positive PCR product indicating target gene replacement and negative for the target gene. Complementation was performed by integrating a single copy of the gene under the control of MOP promoter in the pJEB402 vector37.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

The authors thank Henk van Veen and Wikky Tigchelaar for EM, Peter Reinink for phylogenetic graphs and Sara Suliman for advice. Work was supported by AI116604 (DBM and NNvdW), AI111224 (DBM and MM), GM065307 (EO), CA158191 (EO), AI114952 (ST), Dutch Science Foundation (AJM and JB) and a CIHR Foundation Grant (MAB).

Footnotes

Data availability statement. IRBs require confidentiality of patient data and biological material. Distribution of M. tuberculosis strains is subject to biosafety approvals. Otherwise, all data and reagents are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report (2018).

- 2.Armstrong JA, Hart PD, Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J Exp Med 134, 713–740 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturgill-Koszycki S. et al. , Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science 263, 678–681 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandal OH, Nathan CF, Ehrt S, Acid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 191, 4714–4721 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKinney JD et al. , Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406, 735–738 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell DG, Phagosomes, fatty acids and tuberculosis. Nat.Cell Biol 5, 776–778 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behr MA et al. , Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by wholegenome DNA microarray. Science 284, 1520–1523 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Layre E. et al. , A comparative lipidomics platform for chemotaxonomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chemistry & biology 18, 1537–1549 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galagan JE et al. , The Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory network and hypoxia. Nature 499, 178–183 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Layre E. et al. , Molecular profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies tuberculosinyl nucleoside products of the virulence-associated enzyme Rv3378c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 2978–2983 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan SJ et al. , Biomarkers for Tuberculosis Based on Secreted, SpeciesSpecific, Bacterial Small Molecules. J Infect Dis 212, 1827–1834 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young DC et al. , In vivo biosynthesis of terpene nucleosides provides unique chemical markers of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Chemistry & biology 22, 516–526 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layre E, de Jong A, Moody DB, Human T cells use CD1 and MR1 to recognize lipids and small molecules. Current opinion in chemical biology 23c, 31–38 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pethe K. et al. , Isolation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants defective in the arrest of phagosome maturation. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 101, 13642–13647 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandal OH, Pierini LM, Schnappinger D, Nathan CF, Ehrt S, A membrane protein preserves intrabacterial pH in intraphagosomal Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature medicine 14, 849–854 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyl A, Riefler M, Romanov GA, Schmulling T, Properties, functions and evolution of cytokinin receptors. European journal of cell biology 91, 246–256 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cekic C, Linden J, Purinergic regulation of the immune system. Nature reviews 16, 177–192 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacMicking JD, Cell-autonomous effector mechanisms against mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohde K, Yates RM, Purdy GE, Russell DG, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the environment within the phagosome. Immunol Rev 219, 37–54 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deretic V. et al. , Immunologic manifestations of autophagy. J Clin Invest 125, 75–84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapinos LE, Operschall BP, Larsen E, Sigel H, Understanding the acid-base properties of adenosine: the intrinsic basicities of N1, N3 and N7. Chemistry (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany) 17, 8156–8164 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin MG, Reese CB, Some aspects of the chemistry of N(1)-and N(6)-dimethylallyl derivatives of adenosine and adenine. J Chem Soc Perkin 1 14, 1731–1738 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB, Livesey JH, Kettle AJ, Modeling the reactions of superoxide and myeloperoxidase in the neutrophil phagosome: implications for microbial killing. The Journal of biological chemistry 281, 39860–39869 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buter J. et al. , Stereoselective Synthesis of 1-Tuberculosinyl Adenosine; a Virulence Factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Org Chem 81, 6686–6696 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan S, Yates RM, Russell DG, Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Readouts of Bacterial Fitness and the Environment Within the Phagosome. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J 1519, 333–347 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podinovskaia M, Lee W, Caldwell S, Russell DG, Infection of macrophages with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces global modifications to phagosomal function. Cell Microbiol 15, 843–859 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Duve C. et al. , Commentary. Lysosomotropic agents. Biochem Pharmacol 23, 2495–2531 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadanaciva S. et al. , A high content screening assay for identifying lysosomotropic compounds. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA 25, 715–723 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plantone D, Koudriavtseva T, Current and Future Use of Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine in Infectious, Immune, Neoplastic, and Neurological Diseases: A Mini-Review. Clin Drug Investig, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng X. et al. , Antiinfectives targeting enzymes and the proton motive force. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E7073–7082 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann FM et al. , Edaxadiene: a new bioactive diterpene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 17526–17527 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sani M. et al. , Direct visualization by cryo-EM of the mycobacterial capsular layer: a labile structure containing ESX-1-secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog 6, e1000794 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samanovic MI et al. , Proteasomal control of cytokinin synthesis protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis against nitric oxide. Molecular cell 57, 984–994 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deretic V, Autophagy in tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4, a018481 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Wel N. et al. , M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell 129, 1287–1298 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy KC, Papavinasasundaram K, Sassetti CM, Mycobacterial recombineering. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J 1285, 177–199 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guinn KM et al. , Individual RD1-region genes are required for export of ESAT-6/CFP-10 and for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 51, 359–370 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.