Abstract

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with aggressive disease characteristics resulting in multiple relapses after initial treatment. Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent approved in the US for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL following bortezomib based on results from 3 multicenter phase II studies (2 including relapsed/refractory aggressive NHL and 1 focusing on MCL post-bortezomib). The purpose of this report is to provide longer follow-up on the MCL-001 study (follow-ups were 6.8 [NHL-002], 7.6 [NHL-003], and 52.2 [MCL-001] months). The 206 relapsed MCL patients treated with single-agent lenalidomide (25 mg/day PO, days 1 to 21 every 28-days) had a median age of 67 years (63% ≥65 years), 91% with stage III/IV disease, and 50% with ≥4 previous treatment regimens. With a median follow-up of X, the combined best overall response rate (ORR) was 33% (including 11% with complete remission [CR]/CR unconfirmed CRu). Lenalidomide produced rapid and durable responses with a median time to response of 2.2 months and median duration of response (DOR) of 16.6 months (95% CI: 11.1%–29.8%). The safety profile was consistent and manageable; myelosuppression was the most common adverse event (AE). Overall, single-agent lenalidomide showed consistent efficacy and safety in multiple phase II studies of heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, including those previously treated with bortezomib.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) comprises a diverse group of hematologic malignancies, of which 85% to 90% have a B-cell origin.1 Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) accounted for fewer than 10% of all cases NHL and had an age-adjusted incidence of 0.55 per 100 000 person-years during the period 1992–2004.2–4 The overall median survival in advanced non-blastoid MCL has improved, in large part through use of dose-intensified anthracycline- and cytarabine-based regimens, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, novel targeted agents, and various dose-intensive/high-dose strategies.5,6 Other considerations include the development of more effective salvage regimens, potentially as a bridge to allogeneic transplantation, the only potentially curative option, in eligible patients.7 For all non-blastoid MCL patients, median overall survival (OS) continues to be 4 to 5 years with first-line therapy and 1 to 2 years for relapsed/refractory disease.5,8 Although most patients respond to first-line treatment, the duration of response (DOR) is relatively short, and successive relapses may be accompanied by chemoresistance.8 As such, the goals of therapy are to enhance responses to treatment, extend DOR, and ultimately improve survival.

No standard of care or reliably curative treatment is currently available for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.9,10 The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor temsirolimus was approved for relapsed/refractory MCL in the European Union (EU) in 2009 based on significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared to investigator’s choice.11 With approvals for MCL in both the US and EU, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and ibrutinib also have distinct mechanisms of action.12–17 The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib was approved for relapsed/refractory MCL18,19 based on results from the phase II PINNACLE trial that demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 32% and median DOR of 9.2 months.20,21 Bortezomib was subsequently approved in the US (2014) and EU (2015) for first-line treatment of MCL with VR-CAP (bortezomib/rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/prednisone) showing significantly improved PFS compared to R-CHOP (rituximab/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone) in this setting (25 months vs. 14 months; P < .001).22 Ibrutinib, a small molecule inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, was approved in the US and EU based on phase II results showing a 68% ORR and median DOR of 17.5 months.23

Lenalidomide is an oral immunomodulatory agent with antineoplastic and antiproliferative effects against MCL cells, producing growth inhibition and apoptosis in established MCL cell lines and freshly isolated MCL cells from patients with relapsed/refractory disease.24,25 The objective of this report is to consolidate the data from three phase II clinical trials (one of which served as the basis for FDA approval of lenalidomide in 2013) and to provide long-term efficacy and safety data for lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory MCL. Results from each study were combined to examine consistency among the studies with longer follow-up, as well as to determine in this group of heavily pretreated MCL patients with advanced-stage disease whether prior bortezomib would affect the outcome of subsequent treatment with lenalidomide.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Patients

All relevant institutional review boards or ethics committees approved the research methods used in these studies and all patients were provided written informed consent prior to enrolling. The studies were conducted in accordance with general ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, and Title 21 of the US Code of Federal Regulations. These trials were registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #, , and .

Previously published studies provide detailed patient eligibility criteria.26–28 In brief, eligible patients were ≥18 years of age with biopsy-proven aggressive NHL, including MCL; MCL was confirmed by immunohistochemical measurement of cyclin D1 overexpression or fluorescence in situ hybridization staining for t(11;14)(q13;q32). Patients had relapsed/refractory disease, with at least 1 prior treatment, and were allowed to enroll if relapse occurred following autologous stem cell transplantation. For patients in the MCL-001 study, eligibility criteria included prior therapy with an anthracycline or mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, as well as bortezomib failure (defined as relapse or progressive disease within 12 months from last bortezomib dose following complete response [CR] or partial response [PR] or refractory with <PR after ≥2 cycles of bortezomib).28

2.2 |. Study design

About 206 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL originated from three phase II studies: NHL-002, NHL-003, and MCL-001. NHL-002 was a multicenter, open-label, single-arm trial in 49 patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive NHL (15 with MCL) conducted at 8 centers in the United States and Canada from August 2005 to September 2006 ().26,29 NHL-003 was a global, multicenter, open-label, single-arm study in 217 patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive NHL (57 with MCL) conducted at 48 participating centers in Western Europe (n = 28), the United States (n = 17), and Canada (n = 3) from November 2006 through March 2008 ().27,30 The NHL-002 and NHL-003 studies were completed with final locked data having data cutoffs dates of June 23, 2008 and April 27, 2011, respectively. MCL-001 was a global, multicenter, single-arm, open-label trial conducted at 45 study sites (18 in the United States, 18 in Europe, 8 in Asia, and 1 in Colombia) from January 2009 to March 20, 2013 that included 134 relapsed/refractory patients with MCL (EMERGE, ).28,31 MCL-001 analyses were based on database with data cut-off of April 06, 2016.

Single-agent lenalidomide was administered orally at a dose of 25 mg/day on days 1 to 21 of each 28-day cycle as tolerated for up to 52 weeks (NHL-002) or until disease progression (NHL-003 and MCL-001). Patients with a creatinine clearance 30 to 59 mL/min received 10 mg/day initial dosing in the MCL-001 study.

2.3 |. Assessments and statistical analysis

The primary endpoint for each study was the best ORR (including complete response [CR], CR unconfirmed [CRu], and PR) while receiving lenalidomide, as well as DOR for the MCL-001 study. Efficacy endpoints were measured by 1999 International Workshop Lymphoma Response Criteria (IWLRC) for NHL-002 and NHL-003 and modified IWLRC for the MCL-001 study.20,32,33 Secondary endpoints included time to response, PFS, OS, and safety. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate time-to-event outcomes.34 Efficacy results presented here include a combination of investigator review for NHL-002 and independent central review committee assessment for NHL-003 and MCL-001. Adverse events (AEs) were assessed per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

This study analyzed 206 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who received single-agent lenalidomide in the NHL-002, NHL-003, and MCL-001 studies. Of the 49 patients from NHL-002 who received single-agent lenalidomide, 15 (31%) had relapsed/refractory MCL. Fifty-seven (26%) of 217 patients enrolled in NHL-003 had relapsed/refractory MCL. Patients from the NHL 002/003 trials received lenalidomide until disease progression (maximum of 52 weeks for NHL-002).26,27 The MCL cohort from the NHL-002/003 studies had a median age of 68 years (range, 33–84), with most patients demonstrating good ECOG performance status (0–1, 90%) but with Ann Arbor stage III/IV disease (88%, Table 1). Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens (range, 1–13), with 56% receiving their last anti-lymphoma therapy less than 6 months prior.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics and treatment history of patients with relapsed/refractory MCL treated with lenalidomide

| Characteristic, n (%) | NHL-002/NHL-003 (n = 72) | MCL-001 (n = 134) | Post-bortezomib (n = 157) | All MCL patients (N = 206) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Median (range) | 68 (33–84) | 67 (43–83) | 68 (43–84) | 67 (33–84) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 45 (63) | 85 (63) | 99 (63) | 130 (63) |

| Male | 52 (72) | 108 (81) | 124 (79) | 160 (78) |

| MCL stage disease | ||||

| I/II | 8 (11) | 10 (7) | 12 (8) | 18 (9) |

| III/IV | 63 (88) | 124 (93) | 144 (92) | 187 (91) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0–1 | 65 (90) | 116 (87) | 135 (86) | 181 (88) |

| ≥2 | 7 (10) | 18 (13) | 22 (14) | 25 (12) |

| MIPI score | ||||

| High (≥ 6.2) | 32 (44) | 39 (29) | 54 (34) | 71 (34) |

| Intermediate (5.7–<6.2) | 24 (33) | 51 (38) | 55 (35) | 75 (36) |

| Low (<5.7) | 14 (19) | 39 (29) | 42 (27) | 53 (26) |

| Missing | 2 (3) | 5 (4) | 6 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Elevated LDH (>250 U/L) | ||||

| Yes | 40 (56) | 47 (35) | 62 (39) | 87 (42) |

| No | 31 (43) | 84 (63) | 92 (59) | 115 (56) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Baseline WBC group (109/L) | ||||

| <6.7 | 44 (61) | 67 (50) | 81 (52) | 111 (54) |

| 6.7–<10 | 15 (21) | 41 (31) | 46 (29) | 56 (27) |

| 10–<15 | 5 (7) | 9 (7) | 10 (6) | 14 (7) |

| ≥15 | 8 (11) | 12 (9) | 15 (10) | 20 (10) |

| Missing | 0 | 5 (4) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Tumor burdena | ||||

| High | 30 (42) | 78 (58) | 90 (57) | 108 (52) |

| Low | 33 (46) | 54 (40) | 61 (39) | 87 (42) |

| Missing | 9 (13) | 2 (1) | 6 (4) | 11 (5) |

| Bulky diseaseb | ||||

| Yes | 18 (25) | 44 (33) | 53 (34) | 62 (30) |

| No | 45 (63) | 88 (66) | 98 (62) | 133 (65) |

| Missing | 9 (13) | 2 (1) | 6 (4) | 11 (5) |

| Renal groupc | ||||

| Normal | 40 (56) | 99 (74) | 110 (70) | 139 (67) |

| Moderate | 16 (22) | 28 (21) | 35 (22) | 44 (21) |

| Severe | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Missing | 15 (21) | 6 (4) | 11 (7) | 21 (10) |

| Prior treatment regimens | ||||

| Median (range) | 3 (1–13) | 4 (2–10) | 4 (2–13) | 4 (1–13) |

| Number of regimens | 11 (15) | 0 | 0 | 11 (5) |

| 1 | 12 (17) | 29 (22) | 30 (19) | 41 (20) |

| 2 | 15 (21) | 35 (26) | 41 (26) | 50 (24) |

| 3 | 34 (47) | 70 (52) | 86 (55) | 104 (50) |

| 4 | ||||

| Median time from last prior therapy (range) | 4.1 (0–58.5) | 3.1 (0.3–37.7) | 2.9 (0.1–37.7) | 3.3 (0–58.5) |

| Best response to last prior therapy | ||||

| CR | 22 (31) | 21 (16) | 26 (17) | 43 (21) |

| Cru | 0 | 1 (1) | 1(1) | 1 (<1) |

| PR | 18 (25) | 30 (22) | 31 (20) | 48 (23) |

| SD | 12 (17) | 27 (20) | 33 (21) | 39 (19) |

| PD | 12 (17) | 48 (36) | 55 (35) | 60 (29) |

| Missing | 8 (11) | 7 (5) | 11 (7) | 15 (7) |

| Prior lines of therapy | ||||

| <3 | 23 (32) | 29 (22) | 30 (19) | 52 (25) |

| ≥3 | 49 (68) | 105 (78) | 127 (81) | 154 (75) |

| Relapsed after vs. refractory to last prior therapy | ||||

| Relapsed | 40 (56) | 52 (39) | 58 (37) | 92 (45) |

| Refractory | 26 (36) | 75 (56) | 90 (57) | 101 (49) |

| Missing | 6 (8) | 7 (5) | 9 (6) | 13 (6) |

| Prior therapies | ||||

| Anthracycline-containing | 65 (90) | 133 (99) | 155 (99) | 198 (96) |

| Bortezomib | 23 (32) | 134 (100) | 157 (100) | 157 (76) |

| Rituximab | 67 (93) | 134 (100) | 156 (99) | 201 (98) |

| Relapsed after vs. refractory to prior bortezomib | ||||

| Relapsed | 10 (14) | 51 (38) | 61 (39) | 61 (30) |

| Refractory | 13 (18) | 81 (60) | 94 (60) | 94 (46) |

| Received prior HDT or DITd | 23 (32) | 44 (33) | 49 (31) | 67 (33) |

| Time from last prior systemic anti-lymphoma therapy | ||||

| <6 months | 40 (56) | 96 (72) | 114 (73) | 136 (66) |

| ≥6 months | 32 (44) | 38 (28) | 43 (27) | 70 (34) |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CRu, unconfirmed complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; hyperCVAD, fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MIPI, MCL International Prognostic Index; N/A, not applicable; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; R, rituximab; SD, stable disease; WBC, white blood cells.

High tumor burden was defined by at least 1 lesion ≥5 cm in diameter or at least 3 lesions ≥3 cm in diameter.

Bulky disease was defined at least 1 lesion ≥7 cm in longest diameter.

Creatinine clearance: normal ≥60 mL/min; moderate ≥30 to <60 mL/min; severe <30 mL/min.

High-dose therapy (HDT) or dose-intensive therapy (DIT) included stem cell transplant, hyperCVAD, or R-hyperCVAD.

In the MCL-001 study, eligible patients had received prior anthracycline (or mitoxantrone), cyclophosphamide, and rituximab and had relapsed or progressive disease within 12 months after bortezomib or were refractory to bortezomib.28 The MCL-001 study cohort of 134 patients had a median age of 67 years, with predominantly advanced-stage disease (93% stage III/IV, Table 1). Patients had received a median of 4 prior therapies (range, 2–10), with 78% who had received ≥3 prior treatment regimens.

Because of the similar study design and patient populations in each of these studies, the 3 MCL study populations from NHL-002, NHL-003, and MCL-001 trials have been combined for this analysis. The combined patient populations from NHL-002/003 and the MCL-001 studies showed consistent baseline patient profiles, with or without prior bortezomib. Overall, 63% of MCL patients were 65 years of age or older, 71% had an intermediate to high MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score; 52% showed high tumor burden); 30% presented with bulky disease; at study entry; and 33% had prior high-dose therapy (HDT) or dose-intensive therapy (DIT) including stem cell transplant, hyperCVAD, or R-hyperCVAD. None had received prior ibrutinib.

3.2 |. Efficacy

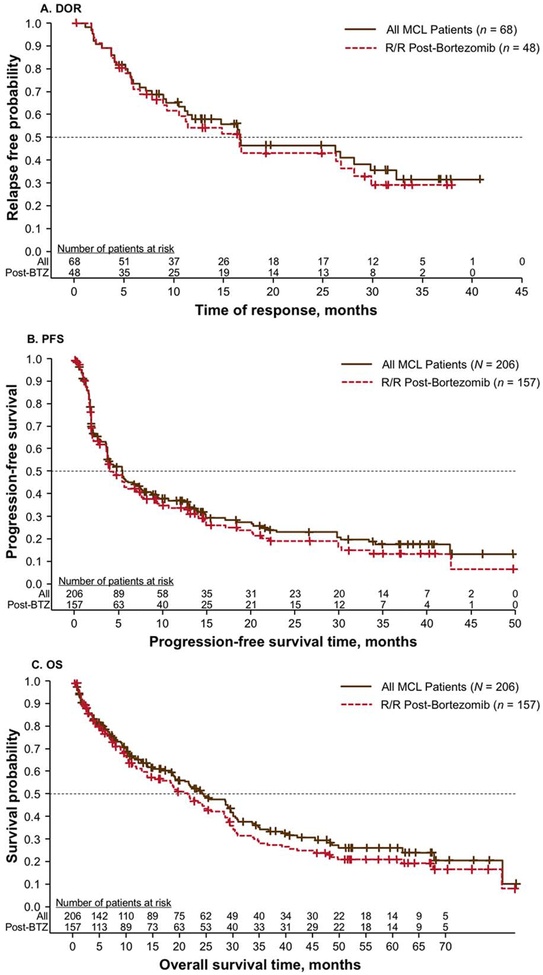

In the combined group of all 206 MCL patients, lenalidomide produced CR/CRu in 11% of patients and PR in 22% of patients, resulting in an ORR of 33% (Table 2). Stable disease was also reached in 32% of patients. The median time to first response was rapid at 2.2 months for all responding patients and 2.0 months for CR/CRu patients. The median DOR was 16.6 months for all responders and 28.1 months for patients with CR/CRu (Figure 1A). Kaplan-Meier estimates for PFS and OS showed a median of 5.5 and 24.4 months, respectively (Figure 1B,C).

TABLE 2.

Efficacy results based on central review for relapsed/refractory MCL patients treated with lenalidomide

| Efficacy parameter | NHL-002/NHL-003a (n = 72) | MCL-001 (n = 134) | Post-bortezomib (n = 157) | All MCL patients (N = 206) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORRb, n (%) | 28 (39) | 40 (30) | 48 (31) | 68 (33) |

| CR/CRu | 10 (14) | 12 (9) | 14 (9) | 22 (11) |

| PR | 18 (25) | 28 (21) | 34 (22) | 46 (22) |

| SD, n (%) | 27 (38) | 38 (28) | 48 (31) | 65 (32) |

| PD, n (%) | 16 (22) | 34 (25) | 39 (25) | 50 (24) |

| Median TTR, months (range) | 1.9 (1.6–24.2) | 3.5 (1.7–15.9) | 2.3 (1.6–15.9) | 2.2 (1.6–24.2) |

| CR/CRu patients | 1.9 (1.6–20.9) | 2.2 (1.8–5.5) | 2.1 (1.6–5.5) | 2.0 (1.6–20.9) |

| Median DOR, months (95% CI) | 16.3 (7.1–NR) | 16.6 (10.4–29.8) | 16.6 (8.9–28.1) | 16.6 (11.1–29.8) |

| CR/CRu patients | NR (NR–NR) | 24.4 (5.1–NR) | 24.4 (11.0–NR) | 28.1 (11.0–NR) |

| PR patients | 8.0 (4.1–32.4) | 14.8 (7.7–29.8) | 11.1 (5.8–26.7) | 11.1 (6.5–26.7) |

| Median PFS, months (95% CI) | 5.8 (3.7–13.5) | 4.0 (3.7–7.2) | 4.5 (3.7–7.2) | 5.5 (3.7–7.4) |

| Median OS, months (95% CI) | NR (NR–NR) | 19.5 (13.7–25.6) | 21.5 (13.7–28.4) | 24.4 (19.0–30.0) |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; CRu, unconfirmed complete response; DOR, duration of response; NR, not reached; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; TTR, time to response. NHL-002/003 data were locked at June 23, 2008 and April 27, 2011, respectively; data cut-off for MCL-001 was April 06, 2016.

Includes data from investigator assessment in NHL-002.

Reflects best response rates. Response data for 23 patients were missing.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for DOR (A), PFS (B), and OS (C) in combined analyses of relapsed/refractory MCL patients and in those who received prior bortezomib. Abbreviations: BTZ, bortezomib; DOR, duration of response; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; R/R, relapsed/refractory.

Similar efficacy results were shown across studies and for patients who had received prior bortezomib therapy. A total of 157 patients were previously treated with bortezomib, including 134 patients from MCL-001 and 23 patients from NHL-002/003. This cohort had an ORR of 31% (9% CR/CRu), with a median time to response of 2.3 months and median DOR of 16.6 months. Median DOR for those with CR/CRu was 24.4 months. Overall median PFS and OS were 4.5 and 21.5 months, respectively. The median follow-up times for NHL-002, NHL-003, and MCL-001 were 13.2, 12.1, and 5.8 months for PFS and 6.8, 7.6, and 52.2 months for OS, respectively.

3.3 |. Response rates across MCL subgroups

ORR with single-agent lenalidomide in the combined cohort was consistent across subgroups as defined by baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, or prior therapy (Table 3). Patients with adverse prognostic factors, including high MIPI score,35 high tumor burden, or bulky disease, and those who relapsed after or were refractory to bortezomib, or who received prior high-dose or high-intensity chemotherapy, had ORRs comparable to the ORR for the entire MCL cohort. One of the highest ORR was observed in patients who received lenalidomide starting ≥6 months after their last anti-lymphoma therapy (47%), and one of the lowest ORR included elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, >250 U/L; 20%)

TABLE 3.

ORR with single-agent lenalidomide in MCL patients from NHL-002, NHL-003, and MCL-001 studies as defined by baseline characteristics and prior therapy

| Characteristic | Groups | n | ORR by subgroup, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 206 | 68 (33) | |

| Age | <65 years | 76 | 25 (33) |

| ≥65 years | 130 | 43 (33) | |

| Sex | Male | 160 | 47 (29) |

| Female | 46 | 21 (46) | |

| MCL stage | I/II | 18 | 5 (28) |

| III/IV | 187 | 62 (33) | |

| ECOG performance status | 0–1 | 181 | 60 (33) |

| 2–4 | 25 | 8 (32) | |

| MIPI score | High (≥6.2) | 71 | 24 (34) |

| Intermediate (5.7–<6.2) | 75 | 23 (31) | |

| Low (<5.7) | 53 | 20 (38) | |

| Missing | 7 | 1 (14) | |

| Elevated LDH (>250 U/L) | Yes | 87 | 17 (20) |

| No | 115 | 51 (44) | |

| Missing | 4 | 0 | |

| Baseline WBC group (109/L) | <6.7 | 111 | 43 (39) |

| 6.7–<10 | 56 | 14 (25) | |

| 10–<15 | 14 | 8 (57) | |

| ≥15 | 20 | 2 (10) | |

| Time from initial diagnosis to first dose | <3 years | 78 | 21 (27) |

| ≥3 years | 128 | 47 (37) | |

| Bone marrow involvement at any time prior to study initiation | Positive | 84 | 25 (30) |

| Negative | 90 | 28 (31) | |

| Indeterminate | 9 | 6 (67) | |

| Missing | 23 | 9 (39) | |

| Tumor burdena | High | 108 | 36 (33) |

| Low | 87 | 32 (37) | |

| Missing | 11 | 0 | |

| Bulky diseaseb | Yes | 62 | 22 (35) |

| No | 133 | 46 (35) | |

| Missing | 11 | 0 | |

| Renal function | Normal | 139 | 45 (32) |

| Moderate | 44 | 12 (27) | |

| Severe | 2 | 1 (50) | |

| Missing | 21 | 10 (48) | |

| Number of regimens | <3 | 52 | 17 (33) |

| ≥3 | 154 | 51 (33) | |

| Relapsed after vs. refractory to last prior therapy | Relapsed | 92 | 35 (38) |

| Refractory | 101 | 29 (29) | |

| Missing | 13 | 4 (31) | |

| Relapsed after vs. refractory to prior bortezomib | Relapsed | 61 | 21 (34) |

| Refractory | 94 | 27 (29) | |

| Received prior HDT or DITc | Yes | 67 | 26 (39) |

| No | 139 | 42 (30) | |

| Time since last prior systemic antilymphoma therapy | <6 months | 136 | 35 (26) |

| ≥6 months | 70 | 33 (47) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; hyperCVAD, fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MIPI, MCL International Prognostic Index; R, rituximab; WBC, white blood cells. NHL-002/003 data were locked at June 23, 2008 and April 27, 2011, respectively; data cut-off for MCL-001 was April 06, 2016.

High tumor burden was defined by at least 1 lesion ≥5 cm in diameter or at least 3 lesions ≥3 cm in diameter.

Bulky disease was defined by at least 1 lesion ≥7 cm in longest diameter.

High-dose therapy (HDT) or dose-intensive therapy (DIT) included stem cell transplant, hyperCVAD, or R-hyperCVAD.

3.4 |. Safety

Lenalidomide was initiated at a dose of 25 mg daily on days 1 to 21 of each 28-day cycle in these phases II trials, and at 10 mg for patients with moderate renal insufficiency characterized by creatinine clearance ≥30 to <60 mL/min (MCL-001 only). Management of toxicities included dose interruption and reduction to the next lowest dose level in 5-mg increments. Overall, the average daily dose of single-agent lenalidomide was 21 mg for all MCL patients and 20 mg for those who had previously received bortezomib. The corresponding median duration of treatment for these combined cohorts was 106 and 101 days, respectively. As of data cut-off, 26% of MCL patients had received ≥12 cycles of lenalidomide. The dose of lenalidomide was interrupted or reduced due to AEs in 59% of all MCL patients and in 58% of those previously treated with bortezomib. In general, dose interruptions or reductions occurred during the first treatment cycle and lasted for a median of 1 week. Discontinuations due to AEs related to lenalidomide occurred in 13% of all MCL patients. Additional dose intensity, modification, and discontinuation information following lenalidomide treatment is available in the Supporting Information.

The safety profile of single-agent lenalidomide in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL was consistent and predictable. Myelosuppression was the most common grade 3/4 toxicity, with neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia occurring in 42%, 28%, and 11% of patients, respectively. The incidence of grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia was 6%. The most common grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicities in MCL patients were fatigue (7%), diarrhea (6%), dyspnea (5%), and pneumonia (4%). Six patients (3%) had grade ≥3 deep vein thrombosis, with 1 case requiring dose interruption. Four patients (2%) had pulmonary embolism that resolved without dose interruption. Tumor flare reaction was reported in 14 MCL patients (7%; grade 1/2). Overall, 113 patients (55%) died during treatment or within 30 days of receiving their last dose of lenalidomide. The most common causes of death were due to MCL (n = 78), other known causes (n = 22), unknown causes (n = 11), and toxicity (n = 2). Detailed grade 3/4 adverse event (≥5% of MCL patients) results for each cohort are available in the Supporting Information.

Thirteen patients (6%) had invasive secondary primary malignancies (SPMs) as of the data cut-off date, but no specific cancer pattern was evident. These patients had a median of 3 (range, 1–5) prior regimens. Invasive SPMs included hematologic malignances in 3 patients (1 each of acute myeloid leukemia [AML], myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS], and MDS to AML) and solid tumors in 10 patients (1 each of bladder cancer/metastases to the liver of unknown origin, bladder transitional cell carcinoma, breast cancer, esophageal carcinoma, metastatic colon cancer, metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, meningioma, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, and small cell lung cancer). The median time to onset of any invasive SPM for 13 patients was 15.4 months (range, 1.2–52.1). Twelve patients with subsequent SPMs had responded to lenalidomide with at least SD, including 3 patients achieving a CR/CRu, and 1 patient who experienced progressive disease.

4 |. DISCUSSION

The availability of new treatments is changing the treatment approach for patients with MCL. Since these agents are now being moved upfront for the initial treatment of MCL, it is important to understand the longer-term outcomes and toxicities of these agents. These data will help design the optimal approach for the MCL patient. In this report, we provide long-term outcome data by combining the analysis of 3 phase II trials. We demonstrate that the ORR to lenalidomide across these studies was 33%, including 11% of patients with CR/CRu. Responses appeared after a median of 2.2 months, lasting for a median of 16.6 months. The ORR is noteworthy, given that patients were heavily pretreated, having previously received a median of 4 treatment regimens, and 63% were ≥65 years of age.

Response to single-agent lenalidomide occurred independently of baseline characteristics and prior treatment history. Comparable ORRs were observed in patients with high tumor burden, bulky disease, or high MIPI, as in the entire MCL cohort. Moreover, ORR with lenalidomide remained consistent in patients who relapsed after or were refractory to bortezomib, and in those who had received prior high-dose or high-intensity therapy. The safety profile of lenalidomide was consistent, predictable, and manageable in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL, consisting mostly of myelosuppression. Dose interruption is recommended for most grade 3/4 AEs, and following sufficient resolution, lenalidomide can be restarted at a reduced dose level or at the same dose level, depending on the nature of the AE.

Other approved therapeutic agents used for relapsed/refractory MCL include bortezomib (approved in the US and EU), ibrutinib (approved in the US and EU), and temsirolimus (approved in the EU). Bortezomib, the first agent approved in the US for treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL, produced a similar ORR (32%) to lenalidomide, although in a population that had mostly received 1 to 2 prior lines of therapy.20,21 Moreover, although not directly comparative, the median DOR with lenalidomide was substantially longer than the 9.2 months reported for bortezomib in the relapsed/refractory MCL population. The most common grade 3/4 AEs for bortezomib included 67% lymphopenia and 13% peripheral neuropathy.20,21 The phase II pivotal study of ibrutinib was performed in 111 patients with a median of 3 prior treatments (range, 1–5), demonstrating a 68% ORR (21% CR) and median DOR of 17.5 months; of the 27 patients previously treated with lenalidomide, 17 (63%) had a response to ibrutinib.23 The safety profile showed a lower incidence of grade 3/4 hematologic AEs (16% neutropenia, 11% thrombocytopenia, 10% anemia), with a few grade 3/4 non-hematologic events (6% diarrhea, 5% abdominal pain, 5% fatigue, requiring continued evaluation with additional study. Grade 3 bleeding events were 2% subdural hematomas, 2% hematuria, and 1% lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Five percent of patients experienced atrial fibrillation. Temsirolimus treatment in 54 patients with a median of 3 prior treatments (range, 2–7) showed a 22% ORR (1 CR), with a median DOR of 7.1 months and grade 3/4 AEs of 59% thrombocytopenia, 15% neutropenia, 20% anemia, 13% asthenia, and 9% infections; most dose reductions were due to thrombocytopenia.36 Bortezomib and temsirolimus were the first agents to show efficacy with an acceptable safety profile in relapsed/refractory MCL. Lenalidomide and ibrutinib both resulted in longer DOR compared to bortezomib and temsirolimus while demonstrating somewhat unique safety profiles; ibrutinib resulted in longer ORR compared to the other 3 drugs. Although no direct comparative studies have been performed and the patient populations from each study are varied and not directly comparable, it is interesting to consider the use of each approved agent based on its efficacy and safety profile, as well as individual patient profiles. Overall, each shows activity in MCL patients who have received several prior therapies.

Recent phase II studies of lenalidomide combined with rituximab (R2) have shown enhanced activity when used in combination in MCL patients both in the first-line and relapsed/refractory settings.37,38 In relapsed/refractory patients, R2 (lenalidomide 20 mg/day, days 1–21/28 with standard-dose rituximab 375 mg/m2/week in cycle 1) demonstrated a 57% ORR (36% CR) and median DOR of 18.9 months.38 Median PFS was 11.1 months and median OS was 24.3 months. R2 was also active in rituximab-resistant patients at doses of lenalidomide 10 mg/day for 2 cycles plus rituximab 375 mg/m2 weekly in cycles 3–5, and followed by continued lenalidomide.39 In 43 patients, R2 treatment resulted in 63% ORR, with a significantly longer median PFS compared with patient’s antecedent regimen where resistance to rituximab was defined (22.2 vs. 9.1 months; P = .0004). First-line R2 (12 cycles of lenalidomide 20 mg/day, days 1–21/28 day cycle plus rituximab 375 mg/m2 weekly during cycle 1, and day 1 of every other subsequent cycle [9 cycles total]) plus lower-dose R2 maintenance (lenalidomide 15 mg/day, days 1–21/28 plus rituximab every other cycle until PD) in 38 patients showed a very high 92% ORR with 64% of patients achieving a CR. Median PFS had not been reached, although 2-year PFS and OS were estimated at 85% and 97%, respectively.37

In summary, long-term data for single-agent lenalidomide demonstrates consistent activity and safety in multiple phase II studies of heavily pretreated patients with advanced-stage relapsed/refractory MCL.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were supported by Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ. The authors received editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript from Bio Connections LLC, funded by Celgene Corporation.

Funding information

Celgene Corporation, Summit, New Jersey

Footnotes

Prior presentation: Results were previously presented in part as posters for the 2013 ASCO and EHA meetings.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Witzig, Goy, and Drach served as consultants/advisors to Celgene Corporation; Drach received compensation for this role. Witzig, Tuscano, and Goy received research funding from Celgene Corporation. Witzig provided expert testimony for Celgene (personally uncompensated). Tuscano and Drach received honoraria from Celgene. Takeshita, Casadebaig Bravo, Zhang, and Fu are employees of Celgene and have received stock and stock options in Celgene. Luigi Zinzani, Habermann, Ramchandren, and Kalayoglu Besisik have no financial relationships to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shankland KR, Armitage JO, Hancock BW. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2012;380:848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghielmini M, Zucca E. How I treat mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;114:1469–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood. 2006;107:265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Wang H, Fang W, et al. Incidence trends of mantle cell lymphoma in the United States between 1992 and 2004. Cancer. 2008;113:791–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrmann A, Hoster E, Zwingers T, et al. Improvement of overall survival in advanced stage mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inamdar AA, Goy A, Ayoub NM, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma in the era of precision medicine-diagnosis, biomarkers and therapeutic agents. Oncotarget. 2016;7:48692–48731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruger WH, Hirt C, Basara N, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for mantle cell lymphoma-final report from the prospective trials of the East German Study Group Haematology/Oncology (OSHO). Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1587–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goy A, Kahl B. Mantle cell lymphoma: the promise of new treatment options. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;80:69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campo E, Rule S. Mantle cell lymphoma: evolving management strategies. Blood. 2015;125:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKay P, Leach M, Jackson R, et al. Guidelines for the investigation and management of mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012; 159:405–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.TORISEL (temsirolimus) prescribing information. United Kingdom: Pfizer Limited; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.VELCADE (Bortezomib) Prescribing Information. Belgium: Janssen-Cilag International NV; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.VELCADE (Bortezomib) for Injection Prescribing Information. Cambridge, MA: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.IMBRUVICA (Ibrutinib) Prescribing Information. Belgium: Janssen-Cilag International NV; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.IMBRUVICA (Ibrutinib) Prescribing Information. Sunnyvale, CA: Pharmacyclics LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.REVLIMID (Lenalidomide) Prescribing Information. United Kingdom: Celgene Europe Limited; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.REVLIMID (Lenalidomide) Prescribing Information. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goy A, Younes A, McLaughlin P, et al. Phase II study of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connor OA. Marked clinical activity of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with follicular and mantle-cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2005;6:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4867–4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goy A, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: updated time-to-event analyses of the multicenter phase 2 PINNACLE study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:520–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian Z, Zhang L, Cai Z, et al. Lenalidomide synergizes with dexamethasone to induce growth arrest and apoptosis of mantle cell lymphoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Leuk Res. 2011;35:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Qian Z, Cai Z, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of lenalidomide and rituximab on mantle cell lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiernik PH, Lossos IS, Tuscano JM, et al. Lenalidomide monotherapy in relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4952–4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witzig TE, Vose JM, Zinzani PL, et al. An international phase II trial of single-agent lenalidomide for relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1622–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3688–3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Habermann TM, Lossos IS, Justice G, et al. Lenalidomide oral monotherapy produces a high response rate in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinzani PL, Vose JM, Czuczman MS, et al. Long-term follow-up of lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: subset analysis of the NHL-003 study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2892–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goy A, Kalayoglu Besisik S, Drach J, et al. Longer-term follow-up and outcome by tumour cell proliferation rate (Ki-67) in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma treated with lenalidomide on MCL-001(EMERGE) pivotal trial. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kane RC, Dagher R, Farrell A, et al. Bortezomib for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5291–5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hess G, Herbrecht R, Romaguera J, et al. Phase III study to evaluate temsirolimus compared with investigator’s choice therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3822–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruan J, Martin P, Shah B, et al. Lenalidomide plus rituximab as initial treatment for mantle cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373: 1835–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang M, Fayad L, Wagner-Bartak N, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with rituximab for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13:716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chong EA, Ahmadi T, Aqui N, et al. Combination of lenalidomide and rituximab overcomes rituximab-resistance in patients with indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1835–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.