Abstract

One of the major roles of interventional EUS is biliary decompression as an alternative to ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Among EUS-guided biliary drainage, EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with transmural stenting (EUS-HGS) may be the most promising procedure since this procedure can overcome the limitation of ERCP. However, EUS-HGS has disadvantages, and the safety issue is still not resolved. In this review, the clinical outcomes and limitations of EUS-HGS will be discussed.

Keywords: Adverse event, EUS, hepaticogastrostomy

INTRODUCTION

EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with transmural stenting EUS-HGS has the following advantages over endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD).[1,2] ERBD is not available when the papilla is not accessible endoscopically. However, EUS-HGS is possible even in surgically altered anatomy or inaccessible papilla. One of the major concerns of ERBD is procedure-related acute pancreatitis. In EUS-HGS, traumatic papillary irritation which can develop acute pancreatitis may be avoided. The stent patency might be longer in EUS-HGS than in ERBD since the stents are not needed to be placed across the stricture site. EUS-HGS shows similar efficacy compared to PTBD when performed by expertise, and may be more comfortable and physiologic to the patients than PTBD because of internal drainage. The overall number of reinterventions seems to be lower after EUS-HGS than after PTBD.[1,3] However, EUS-HGS is still limited because of the complexity of this procedure and the lack of dedicated device for EUS-HGS. Because of the anatomical proximity to the mediastinum, very serious adverse events can occur in EUS-HGS.

EFFICACY OF EUS-GUIDED HEPATICOGASTROSTOMY

Based on 27 clinical studies, the technical and clinical success rates of EUS-HGS were reported to be 96% (range, 65%–100%) and 90% (range, 66%–100%), respectively [Table 1]. The success rate of EUS-HGS was comparable to ERBD and PTBD procedures.[1,2] The technical and clinical success rates of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) were similar to EUS-HGS; however, EUS-CDS has been more widely used because the extrahepatic biliary access through EUS is closer and easier. Nevertheless, EUS-HGS may be preferred over EUS-CDS as an alternative to ERBD, given the clinical situation where ERBD is not feasible. In cases of surgically altered anatomy or duodenal obstruction, EUS-HGS will be the primary choice.

Table 1.

Studies about EUS-HGS

| References, years | Study design | Total number | Technical success, n (%) | Clinical success, n (%) | Early adverse events, n (%) | Profiles of early adverse events (n) | Mean stent patency (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burmester et al., 2003[4] | Retrospective | 1 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | Nil | N/A |

| Kahaleh et al., 2006[5] | Retrospective | 2 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 | Nil | N/A |

| Will et al., 2007[6] | Prospective | 4 | 4 (100) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | Cholangitis (1) | N/A |

| Bories et al., 2007[7] | Retrospective | 11 | 10 (91) | 10 (100) | 4 (36) | Ileus (1) Biloma (1) Stent migration (1) Cholangitis (1) |

388 (95% CI: 203-574) |

| Artifon et al., 2007[8] | Retrospective | 1 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | Nil | N/A |

| Ramírez-Luna et al., 2011[9] | Prospective | 2 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | Stent migration (1) | N/A (range 4-240) |

| Park et al., 2011[10] | Prospective | 31 | 31 (100) | 27 (87) | 6 (19) | Pneumoperitoneum (4) Bleeding (2) |

132 |

| Kim et al., 2012[11] | Retrospective | 4 | 3 (75) | 2 (66) | 1 (25) | Peritonitis (1) | N/A |

| Vila et al., 2012[12] | Retrospective | 34 | 22 (65) | N/A | 11 (29) | Biloma (3) Bleeding (3) Perforation (2) Liver hematoma (2) Abscess (1) |

N/A |

| Park et al., 2013[13] | Prospective | 15 | 14 (93) | 14 (100) | 2 (13) | Biloma (1) Intraperitoneal stent migration (1) | N/A |

| Kawakubo et al., 2014[14] | Retrospective | 20 | 19 (95) | N/A | 7 (35) | Bile leak (2) Stent misplacement (2) Bleeding (1) Cholangitis (1) Biloma (1) |

62 |

| Paik et al., 2014[15] | Prospective | 28 | 27 (96) | 24 (89) | 0 | Nil | 150a (95% CI: 5-295) |

| Artifon et al., 2015[16] | RCT | 25 | 24 (96) | 22 (92) | 5 (20) | Bacteremia (1) Biloma (2) Bleeding (3) |

N/A |

| Umeda et al., 2015[17] | Prospective | 23 | 23 (100) | 23 (100) | 4 (17) | Abdominal pain (3) Bleeding (1) |

120a (range 15-270) |

| Poincloux et al., 2015[18] | Retrospective | 66 | 65 (98) | 61 (94) | 10 (15) | Bile leak (5)b Pneumoperitoneum (2) Liver hematoma (1) Severe sepsis and death (2) |

N/A |

| Park et al., 2015[19] | RCT | 20 | 20 (100) | 18 (90) | 5 (25) | Mild (2) Moderate (3) |

121 |

| Khashab et al., 2016[20] | Retrospective | 61 | 56 (92) | 50 (89) | 12 (20) | Peritonitis (3) Bile leak (2) Cholangitis (2) Intraperitoneal stent migration (2) Bleeding (1) Hepatic collection (1) Shared wire (1) |

N/A |

| Ogura et al., 2016[21] | Retrospective | 26 | 26 (100) | 24 (92) | 0 | Nil | 133a |

| Guo et al., 2016 | Retrospective | 7 | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 1 | Sepsis (1) | N/A |

| Nakai et al., 2016[22] | Retrospective | 33 | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | 3 (9) | Bleeding (1) Abscess (1) Cholangitis (1) |

255a |

| Paik et al., 2017[23] | Retrospective | 16 | 16 (100) | 13 (81) | 2 (13) | Intraperitoneal stent migration (1) Cholecystitis (1) | 402 (95% CI: 97-707) |

| Minaga et al., 2017[24] | Retrospective | 30 | 29 (97) | 22 (76) | 3 (10) | Bile peritonitis (3) | 63a (range 31-201) |

| Cho et al., 2017[25] | Prospective | 21 | 21 (100) | 18 (86) | 4 (19) | Pneumoperitoneum (2) Bleeding (1) Abdominal pain (1) | 166 (95% CI: 95-238) |

| Amano et al., 2017[26] | Prospective | 9 | 9 (100) | 9 (100) | 1 (11) | Abdominal pain (1) | N/A |

| Sportes et al., 2017[3] | Retrospective | 31 | 31 (100) | 25 (81) | 5 (16) | Severe sepsis (2)c Bile leak (2) Bleeding and death (1) |

N/A |

| Moryoussef et al., 2017[27] | Prospective | 18 | 17 (94) | 13 (76) | 1 (6) | Bleeding and death (1) | N/A |

| Oh et al., 2017[28] | Retrospective | 129 | 120 (93) | 105 (88) | 32 (25) | Bacteremia (16) Bleeding (5) Bile peritonitis (4) Pneumoperitoneum (4) Intraperitoneal stent migration (3) |

137 |

| Honjo et al., 2018[29] | Retrospective | 49 | 49 (100) | N/A | 11 (22) | Abdominal pain (6) Bleeding (5) |

N/A |

| Okuno et al., 2018[30] | Prospective | 20 | 20 (100) | 19 (95) | 3 (15) | Cholangitis (3) | 87a |

| Miyano et al., 2018[31] | Retrospective | 41 | 41 (100) | 41 (100) | 6 (15) | Bile peritonitis (4) Cholangitis (1) Stent migration (1) |

112 |

| Paik et al., 2018[2] | RCT | 32 | 31 (97) | 26 (84) | 2 (6) | Pneumoperitoneum (1) Cholangitis (1) |

220 |

| Total | 810 | 774 (96) | 510 (90) | 143 (18) |

aMedian stent patency, bThere were three procedure-related deaths, cThere was one procedure-related death at day 1. RCT: Randomized controlled trial, CI: Confidence interval, N/A: Not applicable

Theoretically, because EUS-HGS stents are placed away from the malignant stricture, the stent patency seems to be longer in EUS-HGS than in ERBD. However, stent patency of EUS-HGS was reported variously, ranging from 62 days to 402 days [Table 1]. Although EUS-HGS may have fewer chance of tumor ingrowth or overgrowth, it can have more cases of stent migration and clogging by food material, and these reasons may shorten the stent patency of EUS-HGS. The location and degree of biliary stricture, presence of gastric or duodenal obstruction, ileus, type and length of the placed stent, and the presence of liver metastasis may affect the stent patency of EUS-HGS. There has been only one prospective study comparing the stent patency between EUS-guided biliary drainage (EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS) and ERBD,[2] and the stent patency was significantly longer in EUS-guided biliary drainage than in ERBD (6-month stent patency 85% vs. 49%, P = 0.001). Ogura et al. reported that EUS-HGS had significantly longer stent patency than EUS-CDS in patients with duodenal obstruction (median 133 vs. 37 days; hazard ratio 0.391, 95% confidence interval 0.156–0.981, P = 0.045), and duodenobiliary reflux caused by duodenal obstruction may contribute shorter stent patency of EUS-CDS.[21] However, in the recent study of our group, there was no significant difference in stent patency between EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS in subgroup analysis of patients with duodenal invasion.[2] EUS-CDS can be performed in patients with type II or III duodenal obstruction (intact duodenal bulb). Further prospective studies comparing EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS among patients with type II or III duodenal obstruction would be warranted.

SAFETY OF EUS-GUIDED HEPATICOGASTROSTOMY

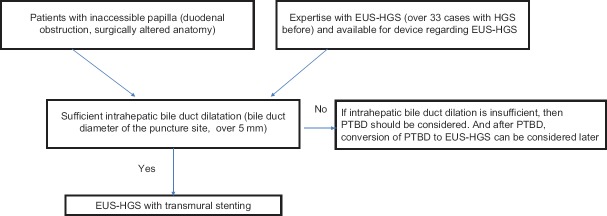

As many clinical data related to EUS-HGS have been reported, this procedure seems to be a safe procedure, and produces fewer procedure-related adverse events than PTBD.[1,32] The overall rate of adverse events was 18% [range, 0%–50%, Table 1]. Common adverse events of EUS-HGS include abdominal pain, self-limiting pneumoperitoneum, bile leak, cholangitis, and bleeding. In rare cases, serious adverse events such as perforation, intraperitoneal migration of the stent, and mediastinitis may happen. Even there have been six deaths associated with EUS-HGS, three of which were associated with bile leak, and the remaining three associated with sepsis.[3,18] EUS-HGS has more types of adverse events than EUS-CDS, and some of them are life-threatening.[15,33] For beginners, more adverse events occur in EUS-HGS than in EUS-CDS.[12] Therefore, EUS-HGS should be tried after sufficient experience of EUS-guided tissue acquisition, pseudocyst drainage, and EUS-CDS. The learning curve of EUS-HGS is still unclear; however, a recent study revealed that over 33 cases might be required to reach the plateau phase for successful EUS-HGS [Figure 1].[28]

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm for EUS-HGS. *When patient have insufficient intrahepatic ductal dilatation and indwelling percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheter, the conversion of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage to EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy may be considered after failed internalization of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage

In order to prevent procedure-related adverse events in EUS-HGS, it is important to reduce the number of accessory changes and shorten the procedure time. For this purpose, a dedicated device for one-step EUS-BD without additional fistula dilation has been introduced, which may result in shortened procedural time with less procedure-related adverse events.[19]

LIMITATIONS OF EUS-GUIDED HEPATICOGASTROSTOMY

Because EUS-HGS is still technically challenging, it is available only in a small number of hospitals so far. There remains a risk of losing access since only a short length of the guide wire left coiled inside the intrahepatic during the exchange of accessories.[34] For a beginner of EUS-HGS, conversion of PTBD to EUS-HGS would provide an additional advantage to achieve the plateau of learning curve for EUS-HGS.[23] By opacification of the intrahepatic through a PTBD catheter, the practitioner more easily finds the optimal puncture site of the intrahepatic. Even if EUS-HGS fails, the risk of adverse events such as cholangitis or bile leak may decrease because of the indwelling catheter.

In advanced hilar stricture or isolated right intrahepatic bile duct obstruction, EUS-HGS has some technical limitations draining the right intrahepatic. However, several techniques of EUS-HGS have been introduced to drain right lobe as follows: (1) Bridging method that inserts uncovered metal stent between right and left intrahepatic first, then inserts the covered metal stent between left intrahepatic and stomach[35] and (2) hepaticoduodenostomy that access right intrahepatic in the duodenum.[36] However, right-sided biliary access may be difficult because of the acute angulation of the access route.

The long distance of the track through the liver parenchyma between the puncture site in the gastric wall and the intrahepatic contributes procedure-related adverse events.[37] The fistula dilation is also a difficult step, and the use of noncoaxial electrocautery during fistula dilation is a risk factor for procedure-related adverse events.[10,20] Another big problem is that the stent could migrate into the peritoneal cavity since there is a free space between the liver and the stomach. The movement of the liver during respiration may also lead to stent migration.[20] To prevent stent migration, the distance between the liver and stomach should be as close as possible, and intrachannel stent release technique should be applied while the HGS stent is deployed.[15,38] Moreover, to prevent stent migration by shortening of the stent, a long stent of 10 cm or more and over 3 cm gastric end of the stent are recommended.[22] In order for EUS-HGS to become more popular, the development of dedicated accessories and devices, and standardization of EUS-HGS technique is mandatory.

CONCLUSIONS

EUS-HGS is a very attractive procedure because it can be performed by the same practitioners of ERCP, and it is possible for endoscopically inaccessible papilla. The clinical studies about EUS-HGS after failed ERCP have shown comparative efficacy with fewer adverse events compared to PTBD. However, since most of the procedures in these studies have been done by experts, EUS-HGS should be performed after sufficient practice and experiences of EUS and ERCP, and surgeons and interventional radiologist should also be available to help with the procedure-related adverse events.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee TH, Choi JH, Park do H, et al. Similar efficacies of endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous drainage for malignant distal biliary obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1011–9.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paik WH, Lee TH, Park DH, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage versus ERCP for the primary palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:987–97. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sportes A, Camus M, Greget M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy versus percutaneous transhepatic drainage for malignant biliary obstruction after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A retrospective expertise-based study from two centers. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:483–93. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17702096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burmester E, Niehaus J, Leineweber T, et al. EUS-cholangio-drainage of the bile duct: Report of 4 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:246–51. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahaleh M, Hernandez AJ, Tokar J, et al. Interventional EUS-guided cholangiography: Evaluation of a technique in evolution. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Will U, Thieme A, Fueldner F, et al. Treatment of biliary obstruction in selected patients by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided transluminal biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2007;39:292–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, et al. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: Results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:287–91. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artifon EL, Chaves DM, Ishioka S, et al. Echoguided hepatico-gastrostomy: A case report. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2007;62:799–802. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322007000600023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramírez-Luna MA, Téllez-Ávila FI, Giovannini M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliodigestive drainage is a good alternative in patients with unresectable cancer. Endoscopy. 2011;43:826–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park DH, Jang JW, Lee SS, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: Predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim TH, Kim SH, Oh HJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage with placement of a fully covered metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2526–32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vila JJ, Pérez-Miranda M, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided cholangiopancreatography for biliary and pancreatic duct drainage: A Spanish national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park DH, Jeong SU, Lee BU, et al. Prospective evaluation of a treatment algorithm with enhanced guidewire manipulation protocol for EUS-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Kato H, et al. Multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:328–34. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik WH, Park DH, Choi JH, et al. Simplified fistula dilation technique and modified stent deployment maneuver for EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5051–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artifon EL, Marson FP, Gaidhane M, et al. Hepaticogastrostomy or choledochoduodenostomy for distal malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP: Is there any difference? Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:950–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umeda J, Itoi T, Tsuchiya T, et al. A newly designed plastic stent for EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy: A prospective preliminary feasibility study (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:390–6.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poincloux L, Rouquette O, Buc E, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP: Cumulative experience of 101 procedures at a single center. Endoscopy. 2015;47:794–801. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park DH, Lee TH, Paik WH, et al. Feasibility and safety of a novel dedicated device for one-step EUS-guided biliary drainage: A randomized trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1461–6. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Penas I, et al. International multicenter comparative trial of transluminal EUS-guided biliary drainage via hepatogastrostomy vs. choledochoduodenostomy approaches. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E175–81. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-109083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogura T, Chiba Y, Masuda D, et al. Comparison of the clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy and hepaticogastrostomy for bile duct obstruction with duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy. 2016;48:156–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Yamamoto N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of a long, partially covered metal stent for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2016;48:1125–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-116595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paik WH, Lee NK, Nakai Y, et al. Conversion of external percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage to endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy after failed standard internal stenting for malignant biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2017;49:544–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minaga K, Takenaka M, Kitano M, et al. Rescue EUS-guided intrahepatic biliary drainage for malignant hilar biliary stricture after failed transpapillary re-intervention. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4764–72. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho DH, Lee SS, Oh D, et al. Long-term outcomes of a newly developed hybrid metal stent for EUS-guided biliary drainage (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1067–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amano M, Ogura T, Onda S, et al. Prospective clinical study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage using novel balloon catheter (with video) J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:716–20. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moryoussef F, Sportes A, Leblanc S, et al. Is EUS-guided drainage a suitable alternative technique in case of proximal biliary obstruction? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:537–44. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17702614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh D, Park DH, Song TJ, et al. Optimal biliary access point and learning curve for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy with transmural stenting. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:42–53. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16671671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honjo M, Itoi T, Tsuchiya T, et al. Safety and efficacy of ultra-tapered mechanical dilator for EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy and pancreatic duct drainage compared with electrocautery dilator (with video) Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:376–82. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_2_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuno N, Hara K, Mizuno N, et al. Efficacy of the 6-mm fully covered self-expandable metal stent during endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy as a primary biliary drainage for the cases estimated difficult endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A prospective clinical study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1413–21. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyano A, Ogura T, Yamamoto K, et al. Clinical impact of the intra-scope channel stent release technique in preventing stent migration during EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:1312–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3758-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharaiha RZ, Khan MA, Kamal F, et al. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage in comparison with percutaneous biliary drainage when ERCP fails: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogura T, Higuchi K. Technical tips for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3945–51. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savides TJ, Varadarajulu S Palazzo L; EUS 2008 Working Group. EUS 2008 working group document: Evaluation of EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogura T, Sano T, Onda S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for right hepatic bile duct obstruction: Novel technical tips. Endoscopy. 2015;47:72–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park DH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage of hilar biliary obstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:664–8. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulay BR, Lo SK. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018;28:171–85. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderloni A, Attili F, Carrara S, et al. Intra-channel stent release technique for fluoroless endoscopic ultrasound-guided lumen-apposing metal stent placement: Changing the paradigm. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E25–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-122009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]