Abstract

EUS-guided biliary drainage (BD) is an option to treat obstructive jaundice when ERCP drainage fails. These procedures represent alternatives to surgery and percutaneous transhepatic BD and have been made possible through the continuous development and improvement of EUS scopes and accessories. The development of linear sectorial array EUS scopes in early 1990 brought a new approach to the diagnostic and therapeutic dimensions of echoendoscopy capabilities, opening the possibility to perform puncture over a direct ultrasonographic view. Despite the high success rate and low morbidity of BD obtained by ERCP, difficulty can arise with an ingrown stent tumor, tumor gut compression, periampullary diverticula, and anatomic variation. The EUS-guided technique requires puncture and contrast of the left biliary tree. When performed from the gastric wall, access is obtained through hepatic segment III. Diathermic dilation of the puncturing tract is performed using a 6F cystotome and a plastic or metallic stent. The technical success of hepaticogastrostomy is near 98%, and complications are present in 15%–20% of cases. The most common complications include pneumoperitoneum, bilioperitoneum, infection, and stent dysfunction. To prevent bile leakage, we used a special partially covered stent (70% covered and 30% uncovered). Over the last 15 years, the technique has typically been performed in reference centers, by groups experienced with ERCP. This seems to be a general guideline for safer execution of the procedure.

Keywords: Biliary drainage, EUS, hepaticogastrostomy

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic biliary stenting is the method used most commonly to treat obstructive jaundice. In 3%–12% of cases, selective cannulation of the major papilla fails and surgery or percutaneous biliary drainage (BD) is required. Percutaneous techniques of BD (PTBD) have a high rate of complication as bleeding or peritoneal bile leakage (20%–30%), and the morbidity and the mortality of surgery for such palliative procedures are, respectively, of 35%–50% and 10%–15%. A new technique for BD using EUS- and EUS-guided puncture of the bile duct (common bile duct or left hepatic duct) is now possible. Using EUS guidance and dedicated accessories, it is now possible to create biliodigestive anastomosis.

The aim of this chapter is:

To describe the material needed for hepaticogastrostomy

To describe the technique of EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy

To describe the place of these techniques today in comparison with ERCP.

MATERIALS

Interventional echoendoscopes

Around 1990, the Pentax-Corporation developed an electronic convex curved linear array echoendoscope (FG32UA) with an imaging plane in the long axis of the device that overlaps with the instrumentation plane. This EUS scope, equipped with a 2.0 mm working channel, enabled fine-needle biopsy under EUS guidance (EUS fine-needle aspiration [FNA]). However, the relatively small working channel of the FG 32UA was a drawback for pseudocyst drainage because it necessitated exchange of the EUS scope for a therapeutic duodenoscope to insert either a stent or nasocystic drain. To enable stent placement using an EUS scope, the EUS interventional echoendoscopes (FG 38X, EG 38UT and EG 3870UTK) were developed by Pentax-Hitachi. The FG 38X has a working channel of 3.2 mm, which allows for the insertion of an 8.5-F stent or nasocystic drain. The EG38UT and EG3870UTK have a larger working channel of 3.8 mm, with an elevator that allows for the placement of a 10F stent.[1,2,3] More recently, a new generation of therapeutic EUS scope (EG38UJ10) is available with a 4.0 mm working channel [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

New therapeutic EUS scope with large working channel (4.0 mm)

The Olympus Corporation has also developed convex array EUS scopes. UCT160-OL5, offer a large working channel (3.7 mm). The UCT160-OL5 provides a 150° ultrasound scanning range when connected to the EU-C60 ultrasound center.

The Fujinon corporation has also developed a therapeutic EUS scope. The EG-580UT, an ultrasound endoscope with Forceps Elevator Assist which enables convex scanning, was developed for therapeutic interventions. The endoscope has a large working channel of 3.8 mm and is equipped with an Albarran lever.

Needles and accessories for drainage

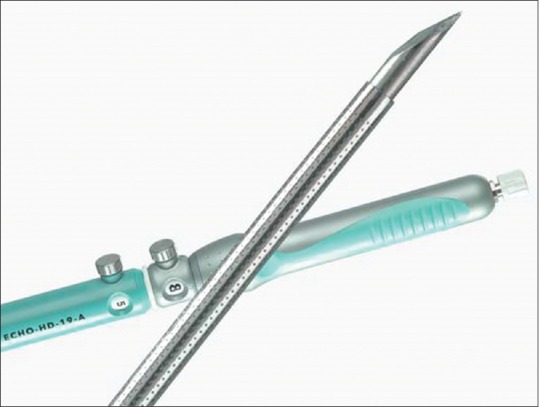

Using a 19G FNA needle (Wilson-Cook Corporation), a 0.035-inch guidewire can be inserted through the needle into the dilated bile duct. However, one of the main problems during these new techniques mainly hepaticogastrostomy is the difficulty manipulating the wire guide through the 19 gauge EUS needle. The main issue was “stripping” of the wire coating, which in turn created a risk of leaving a part of the wire coating in the patient and also the impossibility of continuing the procedure and inserting the stent. To solve this problem, we worked with Cook Medical to design a special needle called the EchoTip® Access Needle* [Figure 2]. This needle is original because the stylet is sharp, and it is relatively easy to insert the needle into the bile duct, the pancreatic duct, or a pseudocyst. When the stylet is withdrawn, the needle left in place is smooth and the manipulation of the wire guide is easy and the device is designed to decrease the possibility of the wire stripping.

Figure 2.

EchoTip® Access Needle (Cook medical, Wiston Salem, US)

Technique for biliary duct drainage under EUS guidance

The proximity of the EUS device to the obstruction area results in a higher resolution than computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, and EUS is a minimally invasive procedure with a lower complication rate compared with ERCP. EUS-guided cholangiography and pancreatography were first described by Wiersema et al. Subsequently, EUS-guided transmural BD was reported by Giovannini et al. as well as by Burmester et al.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

Technique of left hepaticogastrostomy under EUS guidance

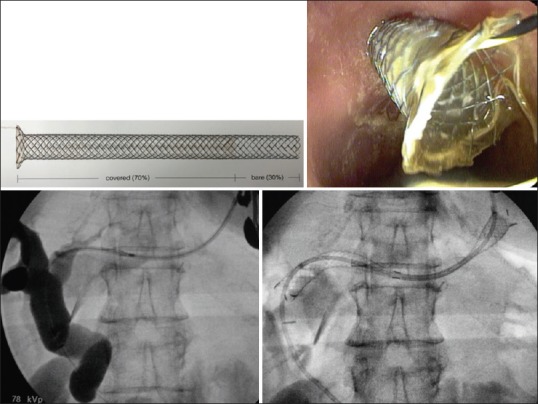

EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy was first reported by Burmester et al.[6] in 2003. The technique is also similar to EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. By using an interventional echoendoscope, the dilated left hepatic duct (segment III) was well visualized. Hepaticogastrostomy under EUS guidance was then performed under combined fluoroscopic and ultrasound guidance, with the tip of the echoendoscope positioned such that the inflated balloon was in the middle part of the small curvature of the stomach. A needle (19G, EchoTip® Access Needle, Cook Ireland Ltd., Limerick, Ireland) is inserted transgastrically into the distal part of the left hepatic duct, and contrast medium is injected for demonstrating dilated biliary ducts. The needle is exchanged over guidewire; a 6F cystostome is then used to enlarge the channel between the stomach and the left hepatic duct. The cystostome is introduced by using cutting current. After exchange over a guidewire (0.035-inch diameter), a dedicated hepaticogastrostomy stent is introduced; this stent is a partially covered metallic stent (70% covered to prevent the bile leakage and 30% uncovered to prevent the migration; the uncovered part is introduced in the bile duct). We use the GIOBOR metallic stent (TaeWoong Taewoong-Medical Co, Seoul, South Korea) or the Hanaro stent (Mi-TECH Mi-TECH-Medical Co, Seoul, South Korea). Hepaticogastrostomy is sometimes combined with the placement of an additional plastic stent (7F, 10 cm double pigtails) to prevent the migration of the metallic stent [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Hepaticogastrostomy using a GIOBOR stent (Taewong Medical, Seoul, South Korea)

Place of the biliodigestive anastomosis guided by EUS in comparison with ERCP

ERCP is the gold standard technique for the drainage of obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic cancer. Success rate of biliary stenting using ERCP is around 80%–85%, but ERCP may fail to selectively cannulate the papilla or fail to reach the papilla at all, in the case of duodenal obstruction.

The percutaneous procedure is the accepted alternative, but these new techniques of BD using EUS guidance represent an additional alternative. PTBD have a high rate of complication as bleeding or peritoneal bile leakage (20%–30%) and the morbidity and the mortality of surgery for such palliative procedures are, respectively, of 35%–50% and 10%–15%. One previous study prospectively compared EUS-BD (choledochoduodenostomy [CD]) and PTBD. Twenty-five individuals were randomized (13 EUS-CD and 12 PTBD). All procedures were technically and clinically successful in both groups. After 7-day follow-up, there was a significant reduction in total bilirubin in both groups (EUS-CD, 16.4–3.3; P = 0.002 and PTBD, 17.2–3.8; P = 0.01), although no difference was noted comparing the two groups (EUS-CD to PTBD; 3.3 vs. 3.8; P = 0.2). There was no difference between groups in the rates of complications (P = 0.44, EUS-CD [2/13; 15.3%], PTBD [3/12; 25%]). Costs were also similar in both groups ($5673-EUS-CD vs. $7570-PTBD; P = 0.39). The authors concluded that EUS-CD can be an effective and safe alternative to PTBD with similar success, complication rate, cost, and quality of life.[11]

The advantages of EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy over PTBD include puncture of the biliary tree with real-time US when using color-Doppler information to limit the possibility of vascular injury, the lack of ascites in the interventional field when present in the peritoneum, and the lack of an external drain. There are some reports about that the extrahepatic approach has a greater chance of complication than the intrahepatic approach. However, Itoi et al. reported the limitations of intrahepatic approach as follows: (i) nonapposed gastric wall and the left liver lobe, with a certain displacement between the puncture site of the gastric wall and intrahepatic bile duct, resulting in possibility of procedure failure, (ii) risk of mediastinitis with a transesophageal approach, (iii) difficulty of puncture in case of liver cirrhosis, (iv) risk of injuring the portal vein, and (v) necessitating the use of small caliber stents or MS with a small-diameter delivery device.

To date, 42 studies with 1192 patients about EUS-BD have been reported. The cumulative technical success rate (TSR), functional success rate (FSR), and adverse-event rate are 94.71%, 91.66%, and 23.32%, respectively. The common adverse events associated with EUS-BD were bleeding (4.03%), bile leakage (4.03%), pneumoperitoneum (3.02%), stent migration (2.68%), cholangitis (2.43%), abdominal pain (1.51%), and peritonitis (1.26%).[12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]

One meta-analysis that compared transduodenal (TD) and transgastric (TG) approaches for EUS-BD regarding efficacy and safety included ten studies. Compared with the TG approach, the TSR, FSR, and adverse-event rate of the TD approach had pooled odds ratios of 1.36 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–2.81; P > 0.05), 0.84 (95% CI, 0.50–1.42; P > 0.05) and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.36–1.03; P > 0.05), respectively, which indicated no significant difference in the TSR, FSR, or adverse-event rate between groups.[32]

What stent should be used?

From a clinical standpoint, the most relevant technical choice appears to be the type of stent. It is difficult to draw significant conclusions from the published reports since no formal comparisons have been made between the different types of stents. Covered (total or partially) self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) appears to be a better option for three reasons. First, on full expansion, SEMS effectively covered the puncture/dilation tract, which would in theory prevent the bile leakage. Second, their larger diameter provides better long-term patency, which would decrease the need for stent revisions. Finally, if dysfunction by ingrowth or clogging occurs, management is somewhat less challenging than with plastic stents because a new stent (plastic or SEMS) can easily be inserted through the occluded SEMS in place. In contrast, exchanging a clogged plastic transmural stent usually requires over-the-wire replacement because free-hand removal involves the risk of track disruption with subsequent guidewire passage into the peritoneum. Uncovered SEMS could allow the leak of bile to peritoneum and possible biloma formation. These presumed advantages of covered SEMS must be balanced against the fact that transmural SEMS insertion and deployment are somewhat more demanding than they are at ERCP. In particular, the serious risk of foreshortening and bile peritonitis should be prevented with careful attention to detail.

For hepaticogastrostomy, we use now a new dedicated stent; this stent is partially covered metallic stent(70% covered to prevent the bile leakage and 30% uncovered to prevent the migration). We use the GIOBOR metallic stent (TaeWoong Taewoong-Medical Co, Seoul, South Korea) or the Hanaro stent (Mi-TECH Mi-TECH-Medical Co., Seoul, South Korea). Hepaticogastrostomy is sometimes combined with the placement of an additional plastic stent (7F, 10 cm double pigtail) to prevent the migration of the metallic stent.

CONCLUSION

EUS-BD is a useful tool in case of failure of ERCP with a high rate of technical success and clinical efficacy. Morbidity rate is high during BD requiring experienced team. Although data have demonstrated EUS-BD can be safe and effective, EUS-BD drainage remains one of the most technically challenging therapeutic EUS interventions. Hepaticogastrostomy is the technique of choice in case of malignant duodenal involvement or altered anatomy.

At this time, we advocate that these procedures should only be performed in appropriately selected patients by experienced endoscopists trained in both, EUS and ERCP, with well-trained surgical backup available.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giovannini M, Pesenti CH, Bories E, et al. Interventional EUS: Difficult pancreaticobiliary access. Endoscopy. 2006;38(Suppl 1):S93–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-946665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahaleh M. EUS-guided cholangio-drainage and rendezvous techniques. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;9:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimm H, Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. Endosonography-guided drainage of a pancreatic pseudocyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:170–1. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannini M. EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;9:32–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannini M. Ultrasound-guided endoscopic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:183–200. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6918(03)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burmester E, Niehaus J, Leineweber T, et al. EUS-cholangio-drainage of the bile duct: Report of 4 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:246–51. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannini M, Dotti M, Bories E, et al. Hepaticogastrostomy by echo-endoscopy as a palliative treatment in a patient with metastatic biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1076–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, et al. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: Results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:287–91. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Téllez-Ávila FI, Duarte-Medrano G, Gallardo-Cabrera V, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transhepatic antegrade self-expandable metal stent placement in a patient with surgically altered anatomy. Endoscopy. 2015;47(Suppl 1):E643–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park DH, Koo JE, Oh J, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with one-step placement of a fully covered metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction: A prospective feasibility study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2168–74. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artifon EL, Aparicio D, Paione JB, et al. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:768–74. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825f264c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Miranda M, de la Serna C, Diez-Redondo P, et al. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography as a salvage drainage procedure for obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:212–22. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i6.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson JA, Hoffman B, Hawes RH, et al. EUS in patients with surgically altered upper GI anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:947–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park DH, Song TJ, Eum J, et al. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with a fully covered metal stent as the biliary diversion technique for an occluded biliary metal stent after a failed ERCP (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Püspök A, Lomoschitz F, Dejaco C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided therapy of benign and malignant biliary obstruction: A case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1743–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, et al. Temporary endosonography-guided biliary drainage for transgastrointestinal deployment of a self-expandable metallic stent. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:637–40. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita N, Sugawara T, Noda Y, et al. Snare-over-the-wire technique for safe exchange of a stent following endosonography-guided biliary drainage. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2008.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Miranda M, De la Serna C, Diez-Redondo MP, et al. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography (ESCP) as the primary approach for ductal drainage after failed ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:AB136. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i6.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Will U, Thieme A, Fueldner F, et al. Treatment of biliary obstruction in selected patients by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided transluminal biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2007;39:292–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maranki J, Hernandez AJ, Arslan B, et al. Interventional endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholangiography: Long-term experience of an emerging alternative to percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Endoscopy. 2009;41:532–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eum J, Park DH, Ryu CH, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with a fully covered metal stent as a novel route for natural orifice transluminal endoscopic biliary interventions: A pilot study (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horaguchi J, Fujita N, Noda Y, et al. Endosonography-guided biliary drainage in cases with difficult transpapillary endoscopic biliary drainage. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:239–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artifon EL, Chaves DM, Ishioka S, et al. Echoguided hepatico-gastrostomy: A case report. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2007;62:799–802. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322007000600023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chopin-Laly X, Ponchon T, Guibal A, et al. Endoscopic biliogastric stenting: A salvage procedure. Surgery. 2009;145:123. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iglesias-García J, Lariño-Noia J, Seijo-Ríos S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound for cholangiocarcinoma re-evaluation after wallstent placement. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:236–7. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082008000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins FP, Rossini LG, Ferrari AP. Migration of a covered metallic stent following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy: Fatal complication. Endoscopy. 2010;42(Suppl 2):E126–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary procedures: Report of 38 cases. Endoscopy. 2008;40(Suppl 1):A55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artifon EL, Takada J, Okawa L, et al. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for biliary drainage in unresectable pancreatic cancer: A case series. JOP. 2010;11:597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hara K, Yamao K, Niwa Y, et al. Prospective clinical study of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant lower biliary tract obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1239–45. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramírez-Luna MA, Téllez-Ávila FI, Giovannini M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliodigestive drainage is a good alternative in patients with unresectable cancer. Endoscopy. 2011;43:826–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park DH, Jang JW, Lee SS, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: Predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Artifon EL, Okawa L, Takada J, et al. EUS-guided choledochoantrostomy: An alternative for biliary drainage in unresectable pancreatic cancer with duodenal invasion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]