A 63-year-old Asian Indian female presented with complaints of visual loss in her left eye (OS) while on systemic chemotherapy for central nervous system (CNS) primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (6 weeks after completion of the sixth cycle of R-MPV – rituximab, methotrexate (3.5 g/m2), procarbazine, and vincristine).[1] Her visual acuity was 20/50 in the right eye (OD) and counting fingers at 1 m OS. Examination revealed vitritis in OD and a large, hazy indistinct yellowish submacular lesion in OS [Fig. 1]. Fluorescein angiography (FA) showed diffuse hyperfluorescence in the macular region in the late phase. Swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) revealed a uniform, subretinal hyper-reflective band above the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The patient received intravitreal methotrexate 400 μg/0.1 mL and was asked to continue further cycles of systemic chemotherapy.[2] Intravitreal methotrexate was repeated after 2 weeks. Four weeks after the first injection, there was a complete regression of the submacular deposition. By 8 weeks of follow-up, she had received a total of 10 cycles of R-MPV. Her visual acuity improved to 20/20. At this time, there was no residual CNS disease on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. SS-OCT revealed complete resolution of the hyper-reflective subretinal band with no disruption in that area [Fig. 2]. At her last follow-up 6 months from presentation, her visual acuity is 20/20 in both eyes, and there is no ocular or CNS disease.

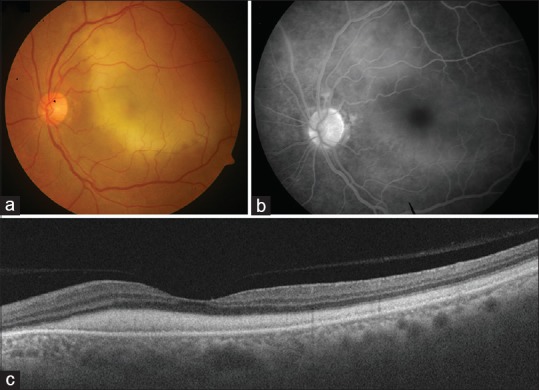

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph of the left eye of the patient described in the report showing presence of a large, diffuse yellowish submacular lesion (a). There is no evidence of any chorioretinal lesion. Fluorescein angiography (FA) shows presence of a diffuse hyperfluorescence in the macular region, corresponding to the yellowish submacular lesion (b). Swept-source optical coherence tomography shows presence of a diffuse sheet-like deposition of subretinal material in the macular region (c)

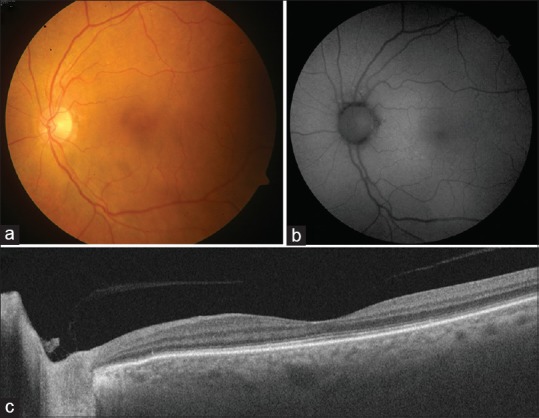

Figure 2.

Follow-up fundus photography of the left eye at 6 weeks after initial presentation showing complete resolution of the yellowish submacular lesion after initiation of intravitreal and systemic chemotherapy (a). Fundus autofluorescence imaging does not reveal any abnormal autofluorescence patterns indicating lack of retinal pigment epithelial damage (b). Follow-up swept-source optical coherence tomography shows resolution of the submacular deposits and normalization of foveal anatomy (c)

In 2014, Pang et al.[3] described a unique series of three patients who developed similar subretinal yellowish deposition and were later diagnosed to be suffering from CNS lymphoma or primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (“paraneoplastic cloudy vitelliform submaculopathy”). A paraneoplastic process, by definition, is an immune-mediated entity due to non-metastatic systemic effects accompanying a malignancy.[4] However, as seen in our patient, the submacular deposits likely represented a malignant process. Given the clinical and multimodal imaging appearance, these submacular deposits do not appear to be composed of lipofuscin like other acquired “vitelliform” lesions.[5] Hence, we propose that this entity be termed as “neoplastic lymphomatous submaculopathy.”

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Morris PG, Correa DD, Yahalom J, Raizer JJ, Schiff D, Grant B, et al. Rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, and vincristine followed by consolidation reduced-dose whole-brain radiotherapy and cytarabine in newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: Final results and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3971–3979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulido JS, Johnston PB, Nowakowski GS, Castellino A, Raja H. The diagnosis and treatment of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A review. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2018;4:18. doi: 10.1186/s40942-018-0120-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pang CE, Shields CL, Jumper JM, Yannuzzi LA. Paraneoplastic cloudy vitelliform submaculopathy in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:1253–61.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maverakis E, Goodarzi H, Wehrli LN, Ono Y, Garcia MS. The etiology of paraneoplastic autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42:135–44. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freund KB, Laud K, Lima LH, Spaide RF, Zweifel S, Yannuzzi LA. Acquired vitelliform lesions: Correlation of clinical findings and multiple imaging analyses. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 2011;31:13–25. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181ea48ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]