Abstract

Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions include an explicit focus on coaching parents to use therapy techniques in daily routines and are considered best practice for young children with autism. Unfortunately, these approaches are not widely used in community settings, possibly due to the clinical expertise and training required. This article presents the work of the Bond, Regulate, Interact, Develop, Guide, Engage (BRIDGE Collaborative), a multidisciplinary group of service providers (including speech-language pathologists), parents, funding agency representatives, and researchers dedicated to improving the lives of young children with autism spectrum disorder and their families. The group selected and adapted a parent coaching naturalistic developmental behavioral intervention specifically for use with toddlers and their families for community implementation. Lessons learned from the implementation process include the importance of therapist background knowledge, the complexity of working with parents of young children, and needed supports for those working closely with parents, including specific engagement strategies and the incorporation of reflective practice.

Keywords: Naturalistic developmental behavioral intervention, parent coaching, early intervention, reflective practice

NATURALISTIC DEVELOPMENTAL BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

Recent work from leading experts in the field of autism intervention has identified naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions (NDBIs) as empirically and theoretically supported approaches for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).1 Although behavioral and developmental treatments have traditionally come from highly diverse fields, current best practice acknowledges that there is much to learn from both approaches and that key ingredients across methodologies can be successfully integrated. This integration allows children who receive NDBIs to benefit from consistent skill acquisition guided by more structured behavioral techniques within the context of engaging interactions that build on the richness of the developmental process. Ensuring that intervention is rooted in our knowledge of development is especially important now, as signs of autism are being identified at increasingly younger ages and children may be receiving specialized treatment as early as their first birthday.2

Although not designed specifically for speech-language pathology, the framework of NDBIs is consistent with best practices for young children and with practices often used in speech-language pathology services.3,4 Common features of NDBIs include individualized treatment goals, child-initiated teaching episodes, ongoing measurement of progress, environmental arrangement to promote interaction, use of behavioral learning principles (including prompting and reinforcement), modeling desired behaviors around the child’s focus of interest, and imitating the child’s language and gestures, among other components. Each of these elements can be used to support a child’s communication skills, including expressive speech and language, receptive language, gesture production, and pragmatic skills. Different branded approaches implement this collection of elements slightly differently (e.g., Early Start Denver Model,5,6 Pivotal Response Training,7,8 Project ImPACT [Improving Parents as Communication Teachers]9), but all focus on the use of intervention strategies in the context of the play and daily routines that are central to the lives of young children.

BENEFITS OF PARENT-IMPLEMENTED INTERVENTION

In synthesizing theory and reviewing empirical evidence regarding early intervention outcomes, it is clear that best practice recommendations emphasize the involvement of parents and caregivers in intervention delivered to young children with ASD.10 To that end, NDBIs often focus on parent coaching, in which interventionists teach the parents of a child with ASD how to use treatment strategies to increase the quantity (time per day) and quality (in the context of a meaningful relationship) of the intervention a child receives. As part of best practice, parent involvement in intervention includes collaborating with clinicians to set goals and priorities for intervention as well as acquiring the tools and strategies to target those goals in the context of home and daily routines. This approach can promote children’s successful use of skills across environments and overtime when they are given repeated opportunities to practice new skills in the variety of contexts they encounter with their parents.11 In addition to the positive impacts of parent-implemented intervention on children,5,10,12 research consistently demonstrates positive impacts of parent-implemented intervention on parents, including reduced parental stress, improved parent responsiveness, and enhanced parent competency in promoting child learning,13–15 among other benefits.

Despite broad endorsement of blended, parent-implemented developmental behavioral interventions for young children as best practice, these approaches remain severely underutilized in community settings.16,17 A main contributor to this underutilization may be the challenges of adequately preparing the broad range of service providers who span the multiple disciplines involved in early intervention to deliver and sustain high-quality, parent-mediated treatments. To successfully use these approaches, service providers not only need to become adept at the intervention techniques themselves, but must also learn to effectively engage and support parents in learning to use the strategies. Too often, professionals trained in early childhood intervention, including speech-language pathologists, overlook the importance of working closely with parents to promote children’s skills. Additionally, they may lack the necessary training to understand how to successfully integrate parents into the intervention process in a meaningful way.

CHALLENGES IN PARENT COACHING AND ENGAGEMENT

Though parent involvement is central to promoting progress for young children with an array of challenges, parents vary in their motivation, skills, abilities, and capacity to engage in parent-implemented interventions for children with ASD. Working with newly diagnosed children with ASD and their parents presents several unique challenges for parent engagement and coaching. For example, the process of receiving a diagnosis of autism or developmental delay may be similar to the experience of bereavement,18,19 and parents’ responses may be similar to those following a trauma or crisis.20,21 This may make it challenging for them to engage in treatment and learn new skills. Although no research has specifically examined the links between parental stress/mental health problems and engagement in their children’s ASD treatment, stress and mental health problems have been linked explicitly to poorer child outcomes in other populations.22 Furthermore, one study found that high parent stress was linked to compromised decision making by therapists regarding appropriate behavior targets in a behavioral intervention.23 Thus, parent stress can impact parents’ engagement through the delivery of the actual intervention itself. Logistically, parents may have multiple children to care for, which can make it challenging to fully participate in intervention sessions. Families may come from a culture where playful interaction with children is not typical, making it difficult or uncomfortable for them to engage in animated play with their child. Furthermore, by the time children receive access to treatment, parents may appear flat or have difficulty playing with their child, because they may have been trying for 9, 12, or even 24 months to engage with them with limited child response. Together, these issues require interventionists to be skilled at understanding what may affect parents’ participation in intervention while discovering ways to increase parent engagement.

Parents’ perceptions of the efficacy of the intervention can also contribute to their engagement in ASD treatment.24,25 When families believe the intervention can result in meaningful change in their child’s functioning, they are more likely to be motivated to engage in the service. In addition, there is some evidence that higher perceived burden of the intervention on the family may reduce treatment engagement.26 Parents’ perceptions about themselves can also impact treatment engagement. For example, when parents believe that their involvement is beneficial and they are equal decision makers in treatment, they are more likely to be active participants in services.27 Relatedly, when parents feel effective in their involvement in the treatment, they are more likely to be involved in it.28

THE BRIDGE COLLABORATIVE

Studies have suggested that approaching parent coaching as a provider-parent collaboration, engaging in shared decision making and enabling collaborative problem solving can facilitate parent engagement in parent coaching interventions and improve treatment outcomes.23,29,30 Supporting interventionists in building effective relationships with parents to promote their child’s development has been a primary goal of a multidisciplinary group of interventionists, parents, researchers, and funding agency representatives, called the BRIDGE Collaborative, over the past 10 years. The BRIDGE Collaborative is a community-academic partnership dedicated to improving the lives of young children with ASD and their families by building capacity for families to receive a particular NDBI in the community.31,32 The following sections highlight key points and data from the work of the collaborative to inform the delivery of effective intervention with young children with ASD, including providing best-practice training that accounts for interventionists’ background knowledge and theoretical orientation, integrating reflective practice to support the intervention process and utilizing specific strategies to explicitly engage parents in the process of treatment.

PROJECT IMPACT FOR TODDLERS

The initial work of the BRIDGE Collaborative involved reviewing an extensive survey of existing approaches to early intervention to support young children and their families, including both those supported in the literature and those widely in use in the community. After considerable examination and an iterative process of community input (e.g., public conferences with intervention developers, surveys, focus groups of parents and providers), the group selected the NDBI Project ImPACT for community implementation.33,34 Project ImPACT is a parent-mediated intervention that focuses on targeting children’s communication, play, social engagement, and imitation skills in the natural environment of daily routines. The effectiveness of Project ImPACT is empirically supported for both in-person and distance parent-training/delivery models.9,35–37 Primary reasons for the selection of this model were the broad applicability to early intervention professionals across multiple disciplines (including speech-language pathology), the parent-implemented approach, the framework of targeting specific child goals in the context of on-going parent-child interactions in daily routines, and the overall fit with shared values across community stakeholders.33 Through pilot testing, expert and clinician feedback, and consultation with Project ImPACT developers, the BRIDGE Collaborative created a toddler-specific adaptation of the approach that included a new parent coaching manual as well as interventionist training materials. This adapted package is called Project ImPACT for Toddlers, and specifically addresses the needs of children 12 to 36 months for whom there are social communication concerns, as well as their families. Though the individual elements of Project ImPACT for Toddlers may seem highly similar to other intervention approaches (e.g., follow the child’s lead, arrange the environment to create natural opportunities to respond), it also focuses specifically on equipping professionals to work closely and collaboratively with parents, which is emphasized throughout the materials and in the training that interventionists receive. Furthermore, the BRIDGE Collaborative integrated reflective practice into the training model to optimally support providers as they engage in the challenging work of working with families of young children with ASD.

TRAINING MODEL

Project ImPACT for Toddlers involves an explicit focus on coaching parents as well as blending key ingredients from differing theoretical approaches (i.e., developmental and behavioral). Although this approach is consistent with best-practice recommendations,10 many providers and community members expressed concerns about effectively combining strategies from the disparate theoretical orientations as well as challenges in fully embracing the parent coaching model. To address these issues, a training program integrating best practices from the adult learning and health care provider behavior change literature was created with the goal of maximizing impact on providers’ clinical practice, including parent coaching skills. The Project ImPACT for Toddlers training model alternates brief didactic information sessions and hands-on practice with feedback. This allows therapists to learn a small chunk of the intervention content each week and quickly provides the opportunity to practice implementing that same content the following week. This process repeats six times, for a total of 12 sessions (six didactic and six coaching). The training content does not focus exclusively on the intervention strategies, but also on the requisite background and accompanying skills to use the intervention effectively (e.g., knowledge of early social-communication development and effective parent coaching techniques). In a parallel process to the intervention’s approach to teaching parents, the hands-on practice sessions provide the opportunity for trainees to see the trainer demonstrate the strategies covered the previous week with a child and then try the strategies themselves while receiving feedback from the trainer. This dynamic and interactive training and chunking of new information is consistent with best practice in the field.38

Following the initial 12-week training (alternating didactic and coaching sessions), the training model recommends an additional 3-month period of practice of the strategies and bimonthly coaching from a supervisor to provide continued support and skill development in using the intervention. During this time, attendance at reflective practice meetings is also encouraged. Depending on the needs of the trainees, coaching sessions can be conducted within the context of ongoing care or can be scheduled explicitly for the purpose of coaching (either individually or with a group). The extended training time provides an opportunity for the trainer to observe the therapist implementing the strategies over time as confidence and skills develop.

USE OF THE INTERVENTION

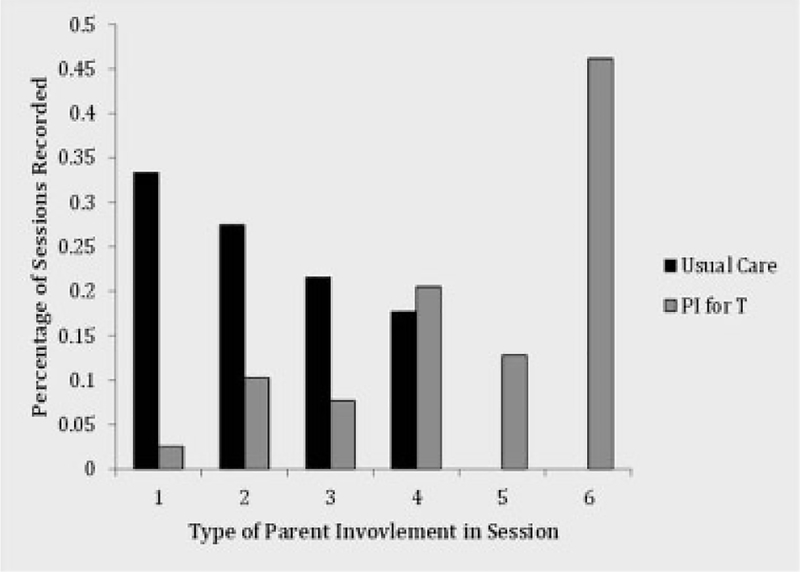

Initial data demonstrate a promising influence on the ability of the Project ImPACT for Toddlers training to promote the use of parent coaching in community early intervention programs. In a small comparison trial, intervention sessions for therapists who had been trained in Project ImPACT for Toddlers as well as those who were delivering usual care were recorded conducting therapy once a month for a period of 4 months. Recordings were categorized by the level of parent involvement and coaching included in the session, from parents observing the therapist providing intervention only to full parent implementation of the techniques with didactic explanations and explicit coaching from the interventionist. Sessions were recorded across 25 therapists, including speech-language pathologists in both the Project ImPACT for Toddlers group and usual care group. Nearly 80% of the sessions (n = 39) from Project ImPACT for Toddlers–trained therapists contained parent coaching, while less than 20% of the usual care recordings contained coaching (n = 51; see Fig. 1, parent coaching considered as types 4 to 6). Importantly, almost 50% of sessions by Project ImPACT for Toddlers–trained interventionists involved the highest quality parent coaching (defined as coaching with feedback and didactic instruction regarding intervention strategies) compared with 0% of sessions from providers in usual care. Fig. 1 contains the full comparison of parent coaching present across the intervention sessions from both groups (as well as definitions of parent coaching types). These data support the positive influence of the Project ImPACT for Toddlers training model on the therapists’ use of parent coaching strategies.

Figure 1.

Parent involvement in intervention sessions across usual care and Project ImPACT for Toddlers (PI for T). Note: Therapists trained in PI for T have a greater proportion of sessions where best-practice parent coaching is present versus those therapists delivering usual care intervention. Parent involvement types:1 = parent observation of session only; 2 = parent-child interaction during session, no coaching from therapist; 3 = therapist models and labels therapy techniques while parent observes; 4 = didactic explanation of techniques to parent; 5 = parent-child interaction during session, with coaching and feedback from therapist on how to use techniques; 6 = parent-child interaction during session, with coaching and feedback from therapist on how to use techniques and didactic instruction on techniques to parent.

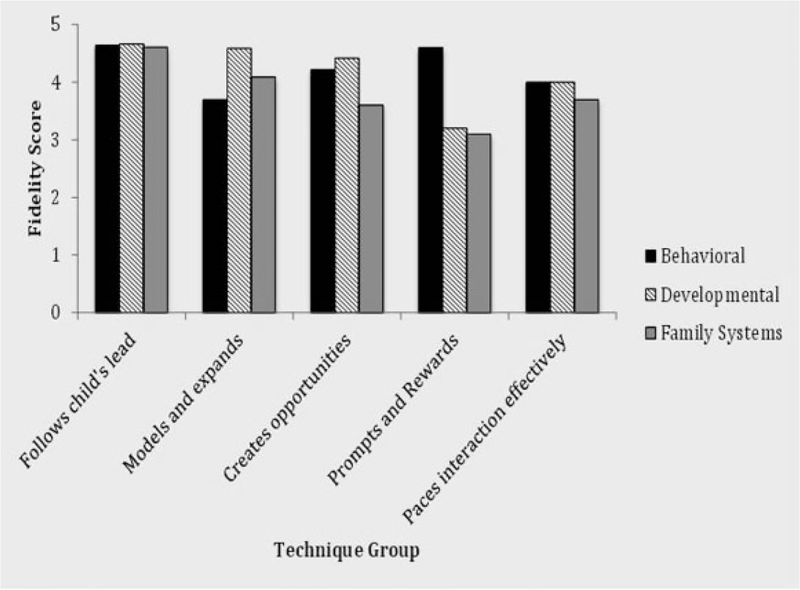

One interesting facet of interventionists’ ability to use Project ImPACT for Toddlers is the influence that background knowledge has on use of specific techniques. In an early pilot study of Project ImPACT for Toddlers in community settings, service providers from a variety of backgrounds in multiple disciplines received training in the intervention and then returned to their service settings to use the approach with families. As part of training, providers completed a demographics survey that included information about their prior training and theoretical background. Providers fell into three groups or orientations: behavioral, developmental, or general family systems. Behavioral providers reported that the majority of their prior training was based in applied behavior analysis (n = 3), whereas those who reported developmental backgrounds had more experience with relationship-based techniques (n = 4). Individuals endorsing general family systems reported counseling and mental health therapy backgrounds (n = 3). Providers also came from a range of primary disciplines, including speech-language pathology (n = 4, two behavioral and two developmental). Video recorded sessions where providers practiced implementing Project ImPACT for Toddlers were scored for intervention fidelity, which is the therapist’s use of each of the individual components that makes up the model. Each component was scored on a 1 to 5 scale where 1 = does not use the component and 5 = uses consistently and competently.

Careful examination of the fidelity data (Fig. 2) revealed that though there were some common areas of strength across all interventionists, the strategies that therapists had trouble using correctly varied systematically according to their theoretical orientation. That is, therapists who self-reported their training as primarily behavioral had different areas of weakness than those therapists who reported their training as predominantly developmental. For example, behavioral therapists, on average, consistently adjusted the level of prompting in accordance with the child’s responding to best promote spontaneous use of skills, but developmentally trained therapists did not. On the other hand, developmentally trained therapists were better able to provide developmentally appropriate expansions on children’s subtle communication and play behaviors, which was an area of difficulty for behaviorally trained therapists. Strategies such as letting the child choose the activity, staying face to face with the child during interaction, imitating child behavior, and modeling language around the child’s focus of attention to give meaning to their actions were used appropriately by all therapists.39 This information was incorporated into subsequent trainings for Project ImPACT for Toddlers to help therapists from varying backgrounds learn unfamiliar strategies. Additionally, this information highlights the fact that self-knowledge of preexisting theoretical biases in conjunction with systematic measurement of strategy can support interventionists as they learn blended interventions.

Figure 2.

Average fidelity score by therapist background. Note: Individual fidelity items are scored on a 1 to 5 scale where 1 = does not implement and 5 = implements consistently and competently. Fidelity items are grouped by similarity/purpose of the techniques. The pattern of fidelity scores indicates differential implementation across types of therapist theoretical backgrounds.

USING REFLECTIVE PRACTICE TO SUPPORT EARLY INTERVENTION PROVIDERS

During the course of the development of Project ImPACT for Toddlers, early childhood practice guidelines began to emphasize the need for reflective practice to support early intervention professionals in their work with complex families. Expanding on more traditional models of supervision, reflective practice is defined by Zero to Three as relationship-based learning occurring between providers and supervisors.40 This relationship builds professional growth and development within one’s own discipline by attending to the emotional content and impact on the provider of the work as well as how provider’s reactions affect the work. This model of mentoring mobilizes a powerful dynamic relationship between supervisor and staff that goes far beyond directional guidance. There is an important qualitative difference in the mentor relationship that parallels the therapeutic process, requiring the ability to listen and wait while allowing the supervisee to discover solutions, concepts, and perceptions independently. The foundational underpinning of reflective practice involves a supportive relationship between a more seasoned professional and an interventionist that is responsive (involves attunement to the supervisee and nonverbal and affective signals), reliable (holds regular meeting time as a priority), and respectful (seeks to understand one another at a deeper level through openness, active listening, and sensitivity).41 Many of the community members in the BRIDGE Collaborative had used reflective practice and understood the value for supporting the practice of parent coaching, particularly with families of young children who may still be processing the information that their children have challenges. Additionally, the team felt that the incorporation of reflective practice in Project ImPACT for Toddlers might further support therapists who were not comfortable or had limited training in engaging parents in the intervention sessions.

As part of reflective practice, therapists learn to use a parallel process to create reflective partnerships with parents, which can assist with the collaborative relationship, thereby improving child outcomes. The practice fosters empathy by allowing therapists to step back and broaden their perspective beyond speech-language therapy and improve the quality of intervention through examination of beliefs and emotions about themselves and others within an interaction and in reflecting about difficult cases. Within this supervision process, therapists build competency in addressing professional challenges in the workplace, cultivate resilience, self-reflect, and clarify thinking to reduce stress and prevent burnout, a key issue impacting community-based services. If the conceptualization of the context of speech-language therapy is broadened to include parents, therapists are mobilizing child development by holding in mind the parent and child relationship.

BENEFITS OF REFLECTIVE PRACTICE FOR SPEECH-LANGUAGE PATHOLOGISTS

Reflective practice for speech-language pathologists has the potential to promote a qualitative difference in practice that builds competency in processing emotions that arise in this challenging work. Reflective practice allows therapists to build a collaborative relationship with the supervisor, to support the navigation of clinical challenges, and to cultivate a deeper understanding of the relational framework in the parent-child relationship.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE IN PROJECT IMPACT FOR TODDLERS

Because of the benefits of reflective practice in early intervention, regular meetings based on the philosophy and strategies of reflective practice were incorporated into a recent Project ImPACT for Toddlers training. Reflective practice sessions began after the conclusion of training on the primary material. These meetings provided an opportunity for therapists who were using Project ImPACT for Toddlers to come together and discuss their successes and challenges in implementing the approach with families, as well as explore their own reactions and experiences with the approach. Formal monthly meetings were held for 3 months with agency leaders, and then leaders were encouraged to return to their own agencies and incorporate the process of reflection with their therapists, either formally (through routine meetings) or informally (through casual conversations). Agency leaders and therapists (n = 32) completed a survey approximately 3 months after the end of their Project ImPACT for Toddlers training and answered several questions specifically about their perspectives on reflective practice. A total of 84% of interventionists agreed that reflective practice meetings were valuable and 92% reported that the meetings supported their learning and use of Project ImPACT for Toddlers strategies. Unfortunately, less than 30% of interventionists reported that reflective practice meetings were ongoing within their agencies, indicating a need for focus on sustainment of this important practice and a method by which to support feasibility. Therapists reported several reasons for not continuing reflective practice meetings, with the majority focusing on the limited time and scheduling difficulties (therapists) as well as the cost of providing additional supervision time for direct service providers (agency leaders).

FURTHER PROMOTION OF PARENT ENGAGEMENT IN INTERVENTION

The use of parent-coaching models and the motivation to involve parents in intervention is not unique to ASD. Researchers and clinicians across multiple children’s service sectors have worked to identify strategies that can best engage parents. Some of these strategies were integrated into Project ImPACT for Toddlers from a toolkit designed for children’s mental health treatment.42,43 Examples of these strategies, as well as example language to implement the strategies, include: (1) listening actively to the parent (e.g., “It sounds like …” or “Let me see if I got this right …”); (2) approaching the parent as a partner, for example by making suggestions rather than giving directions (e.g., “One thing I’ve seen work for others is …” or “You might want to think about …”) or by talking explicitly about partnership (e.g., “Let’s work together to …” or “You and I are partners …”); (3) seeking and utilizing parent input in service delivery, particularly around planning for practice between sessions (e.g., “What do you think about what I said?” or “We covered x and y today; which would you like to focus on at home?”); (4) attending to parents’ strengths and efforts (e.g., “I’m so glad you shared that.” or “That is such a great idea to …”); and (5) working with the parent to identify and address barriers to practice between sessions (e.g., “What will be hard about trying x …?” or “Let’s think about a solution to that challenge together.”). Our preliminary qualitative results indicate that providers find these strategies helpful in promoting parent engagement in the intervention and are able to use them successfully in sessions.43

The specific challenges with social communication for children with ASD may result in parents who appear to have “given up” trying to engage their child, because their past attempts have been met with little success. Additional strategies to address such challenges are explicitly taught in Project ImPACT for Toddlers. These tools include a strategy aiming to find an activity the child responds well to with the interventionist and then providing specific and careful guidance to the parent to replicate that activity. For example, if the child responds to peekaboo by pulling a towel off the interventionist’s face, the experience can be replicated with the parent. By experiencing moments of effective engagement, parents are more likely to increase the amount of time and energy they provide engaging their child. As an additional strategy, interventionists were explicitly encouraged to identify their errors or missteps during interactions with a child, even if over seemingly minor details. For example, if an interventionist displays an energy level that is too high to match a child’s sensory status, the comment, “Uh-oh. Why am I so loud and fast right now? I need to slow down,” allows parents to see what works, what does not, and how to adjust it. In doing so, interventionists model to the parents that making mistakes are normative and to be expected, thereby encouraging parents to attempt to implement novel strategies where they are likely to make mistakes.

CONCLUSIONS

Best practice for young children with ASD involves the blended use of key ingredients from both developmental and behavioral approaches in the context of a parent-mediated intervention. Project ImPACT for Toddlers is one approach to address the need for increased parent coaching in community intervention, including speech-language therapy sessions. Through dynamic training, awareness of theoretical biases, integration of reflective practice, and use of explicit parent engagement techniques, interventionists can learn to build a relationship with the parents and caregivers of children they treat to ultimately improve children’s communication and developmental outcomes.

Learning Outcomes:

As a result of this activity, the reader will be able to (1) summarize the rationale for blended developmental and behavioral approaches to autism intervention; (2) discuss the importance and impact of parent coaching in intervention for young children with autism; (3) identify the challenges of working with parents of young and newly diagnosed children with autism; and (4) evaluate the influence of theoretical orientation on implementation of blended approaches and available support for working with parents.

DISCLOSURES

Financial: This research was supported in part by grants from the Institute of Education Science (R324A130145) and Autism Speaks (8136).

Nonfinancial: All authors are members of the BRIDGE Collaborative. The authors have no additional nonfinancial interests to disclose related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, et al. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45(08):2411–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Psychopathol 2008;20(03):775–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Effects of prelinguistic milieu teaching and parent responsivity education on dyads involving children with intellectual disabilities. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2002;45(06):1158–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingersoll B, Meyer K, Bonter N, Jelinek S. A comparison of developmental social-pragmatic and naturalistic behavioral interventions on language use and social engagement in children with autism. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2012;55(05):1301–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics 2010;125(01):e17–e23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson G, Jones EJH, Merkle K, et al. Early behavioral intervention is associated with normalized brain activity in young children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51(11):1150–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koegel RL, Koegel LK. Pivotal Response Treatments for Autism: Communication, Social, and Academic Development. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koegel RL, Schreibman L, Good A, Cerniglia L, Murphy C, Koegel LK, eds. How to Teach Pivotal Behaviors to Children with Autism: A Training Manual. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingersoll B, Wainer A. Initial efficacy of project ImPACT: a parent-mediated social communication intervention for young children with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43(12):2943–2952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Choueiri R, et al. Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics 2015;136(Suppl 1):S60–S81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter AS, Messinger DS, Stone WL, Celimli S, Nahmias AS, Yoder P. A randomized controlled trial of Hanen’s “More Than Words” in toddlers with early autism symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011;52(07):741–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Remington B, Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, et al. Early intensive behavioral intervention: outcomes for children with autism and their parents after two years. Am J Ment Retard 2007;112(06):418–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estes A, Vismara L, Mercado C, et al. The impact of parent-delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2014;44(02):353–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shire SY, Gulsrud A, Kasari C. Increasing responsive parent-child interactions and joint engagement: comparing the influence of parent-mediated intervention and parent psychoeducation. J Autism Dev Disord 2016;46(05):1737–1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang R, Machalicek W, Rispoli M, Regester A. Training parents to implement communication interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Evid Based Commun Assess Interv 2009;3(03):174–190 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maglione MA, Gans D, Das L, Timbie J, Kasari C; Technical Expert Panel; HRSA Autism Intervention Research—Behavioral (AIR-B) Network. Nonmedical interventions for children with ASD: recommended guidelines and further research needs. Pediatrics 2012;130(Suppl 2):S169–S178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. J Autism Dev Disord 2007;37(10):1902–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elder JH, D’Alessandro T. Supporting families of children with autism spectrum disorders: questions parents ask and what nurses need to know. Pediatr Nurs 2009;35(04):240–245, 253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Searcy K, Cary C. Understanding and Connecting with Parents of Children with Developmental Delays. Long Beach, CA: California Speech and Hearing Association; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders J, Morgan S. Family stress and adjustment as perceived by parents of children with autism or down syndrome: implications for intervention. Child Fam Behav Ther 1997;19:15–32 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seligman MEP, Darling RB. Ordinary Families, Special Children: A Systems Approach to Childhood Disability. New York, NY: Guilford; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbins FR, Dunlap G, Plienis AJ. Family characteristics, family training, and the progress of young children with autism. J Early Interv 1991;15(02):173–184 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss K, Vicari S, Valeri G, D’Elia L, Arima S, Fava L. Parent inclusion in Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention: the influence of parental stress, parent treatment fidelity and parent-mediated generalization of behavior targets on child outcomes. Res Dev Disabil 2012;33(02):688–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowker A, D’Angelo NM, Hicks R, Wells K. Treatments for autism: parental choices and perceptions of change. J Autism Dev Disord 2011;41(10):1373–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore TR, Symons FJ. Adherence to treatment in a behavioral intervention curriculum for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Behav Modif 2011;35(06):570–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hock R, Kinsman A, Ortaglia A. Examining treatment adherence among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Disabil Health J 2015;8(03):407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell PH, Strickland BB, Forme CL. Enhancing parent participation in the individualized family service plan. Top Early Child Spec Educ 1992;11(04):112–124 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solish A, Perry A. Parents’ involvement in their children’s behavioral intervention programs: parent and therapist perspectives. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2008;2(04):728–738 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brookman-Frazee LI, Koegel RL. Using parent/clinician partnership in parent education programs for children with autism. J Posit Behav Interv 2004;6(04):195–213 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burrell TL, Borrego J. Parents’ involvement in ASD treatment: what is their role? Cognit Behav Pract 2012;19(03):423–432 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B, et al. Community-academic partnerships: a systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q 2016;94(01):163–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer AC, Lewis K, Feder JD, Reed S. Building a research-community collaborative to improve community care for infants and toddlers at-risk for autism spectrum disorders. J Community Psychol 2012;40(06):715–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stahmer AC, Brookman-Frazee L, Lee E, Searcy K, Reed S. Parent and multi-disciplinary provider perspectives on earliest intervention for children at-risk for autism spectrum disorders. Infants Young Child 2011;24(04):344–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingersoll B, Dvortscak A. Teaching Social Communication to Children with Autism. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadnick NA, Stahmer A, Brookman-Frazee L. Preliminary effectiveness of Project ImPACT: a parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder delivered in a community program. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45(07):2092–2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wainer AL, Ingersoll BR. Disseminating ASD interventions: a pilot study of a distance learning program for parents and professionals. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43(01):11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wainer AL, Ingersoll BR. Increasing access to an ASD imitation intervention via a telehealth parent training program. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45(12):3877–3890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015; 10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee E, Stahmer AC, Reed S, Searcy K, Brookman-Frazee LI. Differential learning of a blended intervention approach among therapists of varied backgrounds. Paper presented at: International Meeting for Autism Research; May 12–14, 2011; San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fenichel E. Learning through Supervision and Mentorship to Support the Development of Infants, Toddlers, and Their Families: A Source Book. Arlington, VA: Zero to Three; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegel D. Parenting from the Inside Out. London, UK: Penguin Publishing; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haine-Schlagel R, Martinez JI, Roesch SC, Bustos CE, Janicki C. Randomized trial of the Parent and Caregiver Active Participation Toolkit for child mental health treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;21:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haine-Schlagel R, Rieth SR, Dickson KS, Brookman-Frazee LI, Stahmer AC. Mixed method feedback on the integration of parent engagement strategies into an evidence-based parent coaching intervention for young children at risk for ASD. Paper presented at: 2017 International Meeting for Autism Research; May 10–13, 2017, San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]