Abstract.

Poliovirus (PV) environmental surveillance was established in Haiti in three sites each in Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves, where sewage and fecal-influenced environmental open water channel samples were collected monthly from March 2016 to February 2017. The primary objective was to monitor for the emergence of vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs) and the importation and transmission of wild polioviruses (WPVs). A secondary objective was to compare two environmental sample processing methods, the gold standard two-phase separation method and a filter method (bag-mediated filtration system [BMFS]). In addition, non-polio enteroviruses (NPEVs) were characterized by next-generation sequencing using Illumina MiSeq to provide insight on surrogates for PVs. No WPVs or VDPVs were detected at any site with either concentration method. Sabin (vaccine) strain PV type 2 and Sabin strain PV type 1 were found in Port-au-Prince, in March and April samples, respectively. Non-polio enteroviruses were isolated in 75–100% and 0–58% of samples, by either processing method during the reporting period in Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves, respectively. Further analysis of 24 paired Port-au-Prince samples confirmed the detection of a human NPEV and echovirus types E-3, E-6, E-7, E-11, E-19, E-20, and E-29. The comparison of the BMFS filtration method to the two-phase separation method found no significant difference in sensitivity between the two methods (mid-P-value = 0.55). The experience of one calendar year of sampling has informed the appropriateness of the initially chosen sampling sites, importance of an adequate PV surrogate, and robustness of two processing methods.

INTRODUCTION

The goal to eradicate polio was declared by the World Health Assembly in 1988.1,2 The Global Polio Eradication Initiative has used four eradication strategies to reduce the number of polio cases globally from an estimated 350,000 in 1988 to 33 in 2018: 1) high polio vaccination coverage through routine services, 2) supplementary polio immunization activities, 3) outbreak response polio immunization activities in areas where poliovirus (PV) is known or suspected to be circulating, and 4) acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance.3,4 Vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs), vaccine polioviruses that have genetically drifted and phenotypically reverted to become neurovirulent, can emerge from oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV; types 1, 2, or 3) in areas with suboptimal polio vaccination coverage. Wild poliovirus (WPV) was eliminated from the Americas,1 with the last WPV case in the region reported in Peru in 1991.5,6

In 2000–2001, an outbreak of circulating VDPV type 1 (cVDPV1) occurred on the island of Hispaniola, with cases reported in both Haiti (eight cases) and the Dominican Republic (13 cases).7 During the Hispaniola outbreak, to complement AFP surveillance, environmental samples (e.g., wastewater) were collected for PV testing where cVDPV1 cases had been reported and in areas considered high risk. VDPVs type 1, genetically related to those isolated from stool of VDPV1 positive AFP cases, were isolated from environmental samples in Haiti, notably one in Port-au-Prince prior to the detection of clinical cases, and the Dominican Republic demonstrating that environmental surveillance can detect transmission.8

Environmental surveillance can detect PVs excreted by infected humans (the only known PV reservoir) in sewage or fecal-influenced environmental waters, whereas AFP surveillance depends on the notification of clinical disease in individuals. Thereby, environmental surveillance provides a complement to AFP surveillance and became an important component of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) 2013–2018 Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan.9 In July 2014, in response to the 2013–2018 plan, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Technical Advisory Group recommended that PAHO propose options for environmental surveillance in selected settings in the region and urged the implementation of environmental surveillance to support validating the elimination of WPV and absence of VDPVs.10 Consistent with the region’s prioritization, Haiti was among the priority countries listed in the WHO’s Polio Environmental Surveillance Expansion Plan, 2014–2018.9,11

Environmental surveillance was established in Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves, Haiti, in March 2016 with the primary objective to monitor for the emergence and transmission of VDPVs, as well as the importation and transmission of WPVs. Haiti has no established sewer networks; thus, environmental surveillance was conducted at open water canals and a wastewater treatment facility. Characterization was conducted on detected non-polio enteroviruses (NPEVs) and physicochemical parameters of the samples as a main objective to screen environmental sites. The second objective was to compare two environmental sample processing methods: the gold standard two-phase separation method and a filter method (e.g., bag-mediated filtration system [BMFS]). The two-phase method is presently the recommended method of the WHO Global Polio Laboratory Network,11–16 whereas the BMFS has been piloted in Kenya (Nicolette Zhou, personal communication), Mexico, and Pakistan.17,18

With the exception of environmental sampling related to the 2000–2001 cVDPV1 outbreak,8 environmental surveillance for PVs has not been conducted in Hispaniola. This article summarizes the establishment of environmental surveillance during a calendar year (March 2016–February 2017) from two open canals and one wastewater treatment plant in Port-au-Prince, and from three open canals in Gonaïves, Haiti. The results regarding NPEVs as a PV surrogate and the comparison between the two-phase and BMFS concentration methods are presented.

METHODS

The protocol for the presented work was approved by the Haitian Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (Ministry of Public Health and Population [MSPP]) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta (CDC-Atlanta). The human subjects’ research coordinator of the Center for Global Health, CDC-Atlanta, reviewed the protocol and deemed the work to be exempt from institutional review board approval because it was not human subjects research (e.g., no human specimens were collected).

Environmental surveillance site selection.

Three sampling sites within each of two cities, Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves, were selected considering the Global Polio Eradication Initiative recommendations: 1) open canals or water channels downstream of households if a converging sewer network is not established or known, 2) watershed with a population of 100,000 to 300,000 individuals, 3) collection during “maximum effluent flow” (e.g., collection from 6 to 8 am), and 4) capacity to maintain sample integrity in a reverse-cold chain and to deliver samples to the laboratory within 48 hours of collection (Figure 1).19 Aerial maps for each city were used to assist in the site selection process (provided by Novel-t, www.novel-t.ch), where the catchment area and hydrology dynamics were derived from a 30-m terrain model (digital elevation model); geographic coordinates for each site were measured by a handheld GPS device (Montana® 600; Garmin International, Olathe, KS); and watershed populations were estimated from a WorldPop spatial demographic dataset (Department of Geography and Environment, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom).20

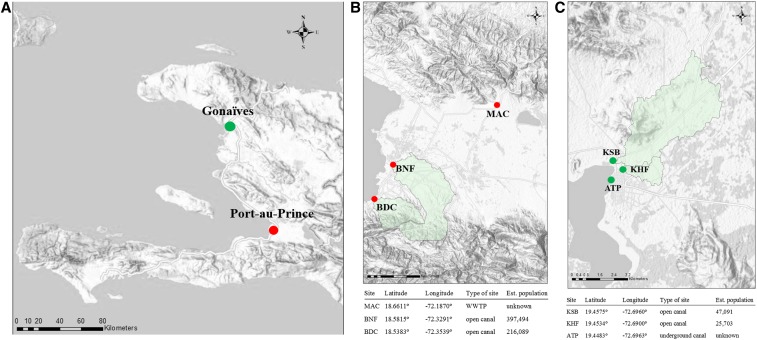

Figure 1.

Haiti poliovirus environmental surveillance sampling sites from March 2016 to February 2017 and associated geographical and estimated population data: (A) Haiti and the cities of Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves; (B) sampling sites in Port-au-Prince: MAC = Morne á Cabri, BNF = Bois Neuf, and BDC = Bois de Chêne; and (C) sampling sites in Gonaïves: KSB = Key Soleil Bridge, KHF = Key Soleil Health Facility, and ATP = Authorité Portuaire. Watersheds for each sampling site are indicated in green shading, except for ATP and MAC where the watershed boundaries could not be determined.

Port-au-Prince sampling sites.

Three sampling sites were established in Port-au-Prince: Morne à Cabri (MAC, 18.6611°, −72.1870°), Bois de Neuf (BNF, 18.5815°, −72.3291°), and Bois de Chêne (BDC, 18.5383°, −72.3539°) (Figure 1B). The MAC sampling site, a wastewater treatment facility operated by the Direction Nationale de l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement (National Directorate for Potable Water and Sanitation), is located on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. The population contributing to the facility could not be defined or estimated. The facility receives raw sewage trucked in from private septic pits, public latrines, and canals, primarily from the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area. The BNF sampling site is the Canal Saint Georges (open canal) at the intersection with Boulevard des Americans (National Route 9) near the Cité Gérard and BNF neighborhoods. The watershed population was estimated to be 397,494. The BDC sampling site is the open canal at the intersection of Rue BDC and Harry Truman Boulevard in Cité de Dieu. The watershed population was estimated to be 216,089.

Gonaïves sampling sites.

Three sampling sites were established in Gonaïves: Key Soleil Bridge (KSB, 19.4575°, −72.6960°), Key Soleil Health Facility (KHF, 19.4534°, −72.6900°), and Autorité Portuaire (ATP, 19.4483°, −72.6963°) (Figure 1C). The KSB sampling site is the open canal downstream from the intersection of Rue Egalité and Avenue Rachette. The watershed population was estimated to be 47,091. The KHF sampling site is the open canal next to a health facility at the intersection of Rue Christophe and Avenue Roland 2. The watershed population was estimated to be 25,703. The ATP sampling site is an underground canal at the intersection of Rue Louverture and Rue du Quai; the canal was accessed via an opening in the street at the intersection of the two streets. It was not possible to estimate the watershed population for this canal because of the hydrological flow being concealed by concrete. The watershed populations at the sampling sites in Gonaïves were much smaller than those recommended in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative environmental surveillance guidelines; however, the city was chosen for sampling because it has the second largest population in the country, in addition to the city’s risk for VDPV emergence and PV circulation due to suboptimal polio vaccination coverage.

Sample collection and frequency.

The Haitian project coordinator and sample collectors were local staff of the MSPP. The project coordinator and sample collectors were trained by CDC-Atlanta and PAHO/WHO staff before the initiation of activities, on sample collection and personal protection procedures through classroom and on-site field training.19 CDC-Atlanta and PAHO/WHO conducted two supervision visits during the 12-month period (March 2016–February 2017).

Two, one-liter wastewater samples were collected approximately every 4 weeks at each sampling site during March 2016–February 2017 using the grab method with a swing sampler (NASCO, Fort Atkinson, WI) with 1-L Nalgene® bottles. Time, date of collection, and sample temperature, as well as weather conditions on collection day and the previous day, were recorded. All samples were stored at 2–8°C immediately after collection and transported on the same day to the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique. On arrival at the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique, the samples were stored at −20°C until shipment on dry ice to the CDC in Atlanta. The samples were maintained at −20°C until processing for virological analyses.

Water quality analyses and additional environmental parameters.

Thirty milliliters of sample from each site was set aside at the time of collection for water quality analyses. Total coliforms and Escherichia coli were analyzed in these sample aliquots for the months of April, May, June, August, September, and November 2016 (Port-au-Prince sites, total n = 16; MAC [n = 6], and BNF and BDC [n = 5 each]; Gonaïves sites, total n = 18; KSB, KHF, and ATP [n = 6 each]). Physicochemical parameters, pH, total dissolved solids, and turbidity were measured in sample aliquots for the same months (Port-au-Prince, total n = 18, MAC, BNF, and BDC [n = 6 each]; Gonaïves, total n = 18, KSB, KHF, and ATP [n = 6 each]). Sample temperature was measured for all samples (with the exception of the February collection). The sample temperature was measured in the field before the samples were placed in the 2–8°C reverse-cold chain, whereas the remaining parameters were tested in the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique environmental laboratory within 24 hours of collection. Total coliforms and E. coli were tested using the defined substrate technology test kit, Colilert®-18 (IDEXX® Laboratories, Westbrook, ME), according to the manufacturer’s directions for the most probable number (MPN) value per 100 mL. Total dissolved solids were measured in parts per million (ppm), and pH was measured using the Hanna portable waterproof meter (Woonsocket, RI). Turbidity in nephelometric turbidity units (NTU) was measured using the Hach portable turbidimeter (Ames, IA).

Ambient air temperature and monthly rainfall data for the time period were obtained from the World Bank Group, Climate Knowledge Portal.21

Concentration of virus in environmental samples.

All samples were processed in parallel for the two virus concentration methods at CDC-Atlanta. Before processing, duplicate 1-L environmental water samples for each environmental site were thawed at room temperature for 24 to 48 hours before processing, combined into a sterile glass beaker with a stir bar to mix for 15 to 30 minutes, and split into duplicate aliquots for each method.

Two-phase separation method.

A volume of 500 mL was concentrated using the two-phase separation method as described in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative Guidelines on Environmental Surveillance for Detection of PV.19 Briefly, the environmental sample was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 1,500 × g. The supernatant was collected and adjusted to a pH 7 to 7.5. The resulting pellet, if any, was retained and stored at 4°C for later addition to the concentrate. Dextran T40 (22% w/w; Pharmacosmos, Holbaek, Denmark), polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG) (29% w/w; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 5 M sodium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) were then added to the supernatant and mixed thoroughly for one hour at 4°C. To allow complete separation, the supernatant–polymer mixture was added to a separatory funnel and incubated overnight at 4°C. After incubation, the lower phase and interphase were collected (approximately 12–15 mL). The stored pellet was added to the concentrate for an average final volume of 14.8 mL. The resulting concentrate was treated with chloroform (20% v/v), agitated for 20 minutes, and concentrated by centrifugation (1,500 × g, 20 minutes, 4°C). Antibiotics (300 IU/mL penicillin and 300 µg/mL streptomycin) were added to the isolated supernatant. The concentrates were inoculated into cell culture for PV isolation the same day, as described below.

Filtration method (BMFS).

The remaining environmental sample (median: 1250 mL, range: 748–1,440 mL) was processed using the BMFS. The lower range of volume processed (e.g., 748 mL) was because of samples with large amounts of sludge or particulates that could not be processed through the BMFS filter medium. The BMFS was described previously for “in-field” virus concentration,22,23 where modifications for “in-laboratory” for this study are briefly described here. Using a peristaltic pump (Masterflex, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL), samples were passed through the ViroCap™ pleated cartridge filter (Scientific Methods, Granger, IN) placed within the reusable filter housing sump (Protolabs, Maple Plain, MN) and a reinforced polypropylene lid (Pentek, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ). The elution solution of 1.5% beef extract–0.05 M glycine solution (pH 9.5) was then added to the filter media. The elution solution was held in the filter housing for 15 minutes, followed by eluting the sample using a bilge pump. The resulting eluted samples (∼70 to 90 mL) were confirmed to have had a pH 9.2 or above and then adjusted to pH 7.0–7.5 using HCl. Secondary concentration was performed with 14% (w/v) PEG 8000 and 1.17% (w/v) NaCl, where the sample and PEG/NaCl were combined, mixed overnight at 4°C, and concentrated by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 4°C, 30 minutes). The final pellet from the secondary PEG/NaCl step was resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0) to a volume of 15 mL to match the final volume of the two-phase separation concentrate. The resulting concentrate was treated with chloroform (20% v/v), agitated for 20 minutes, and the phases separated by centrifugation (1,500 × g, 20 minutes, 4°C). Antibiotics (300 IU/mL penicillin and 300 µg/mL streptomycin) were added to the isolated, upper aqueous phase. The concentrates were inoculated into cell culture for PV isolation the same day, as described in the following text.

Virus isolation.

Polio and other enteroviruses were isolated according to the recommended WHO PV isolation protocol using cell cultures of L20B cells (recombinant murine cells that express human PV receptor) and human rhabdomyosarcoma cells (RD; ATCC CCL-136), followed by detection and intra-typic differentiation of polioviruses by real-time RT-PCR.19,24

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and phylogenetic analysis of enteroviruses.

A total of 54 samples were selected for genotypic characterization: RD cell concentrates from the first passage samples that were confirmed as NPEV by real-time RT-PCR. These included 24 paired two-phase and BMFS samples from Port-au-Prince and three paired samples from Gonaïves. A modification of a published NGS protocol was adapted for high-throughput sequencing of enteroviruses.25 Briefly, viral nucleic acids were extracted from cell culture supernatants using a MagMAX Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit and a KingFisher Flex Purification System (ThermoFisher, Grand Island, NY) with DNase steps to remove DNA. The RNA was subjected to reverse transcription with a primer with eight random nucleotides in the 3′ end, sequence-independent single-primer amplification, and the Illumina library was constructed by using the Nextera XT kit (Illumina; San Diego, CA).26 Normalized library DNA was sequenced using a 500-cycle (2 × 250-bp paired-end) MiSeq v2 kit on an Illumina MiSeq. Bioinformatic analysis was conducted with an in-house CDC NGS pipeline (VPipe) that performs read quality control, de novo assembly to generate contigs, and BLASTn and BLASTx taxonomic classifications to the closest enterovirus, as previously described.25 The consensus enterovirus sequence for each sample was aligned to the closest GenBank reference sequence using MAFFT to annotate the VP1 region.27 In addition to the NGS sequencing of NPEVs, Sanger sequencing was performed for five PV-positive samples by standard Global Polio Laboratory Network methods.28 Five polioviruses were bidirectionally sequenced for their complete VP1 regions (900 to 903 base pairs) using an established PV sequencing method.29 A total of 82 enterovirus VP1 (NPEVs and PVs) were aligned using MAFFT, followed by phylogenetic analysis using RAxML v.8.30 All sequences were deposited in the GenBank sequence database, accession numbers MK000145-233.

Statistical analyses.

For each site and environmental parameter, descriptive statistics were calculated using SAS software (version 9.3). The exact McNemar’s test (mid-P-value = < 0.05) was used to compare isolation of enteroviruses from the two-phase separation and filtration methods (SAS version 9.3).31

RESULTS

Sample collection, water quality analyses, and additional environmental parameters.

For the Port-au-Prince sites (Figure 1A and B), all samples (n = 36) were stored with frozen ice packs after collection and received by the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique within 2 hours of the last sample being collected. The canal samples from the BDC and BNF sites were collected at a median time of 10:10 am, whereas the median collection time for sewage at the MAC wastewater treatment facility was 1:37 pm. For the Gonaïves sites (Figure 1A and C), samples (n = 36) were stored with ice packs after collection and received by the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique within 4 hours of the last sample being collected. Samples from ATP, KSB, and KHF were collected at a median time of 1:00 pm.

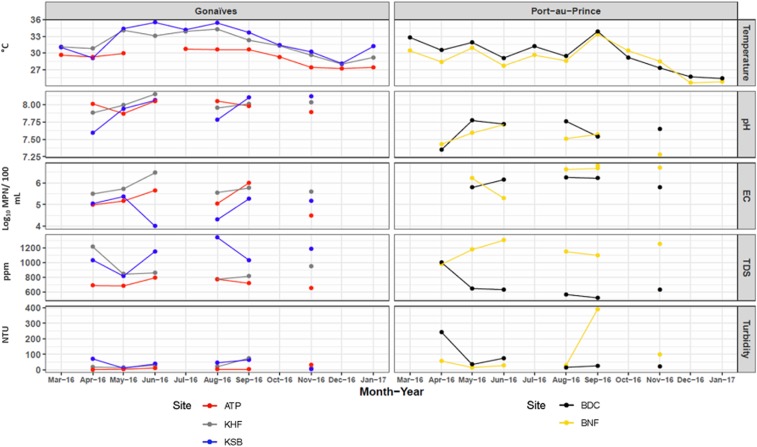

The monthly environmental sample characteristics measured from each site in Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves are shown in Figure 2, with the exception of MAC due to the site’s sample type. Bacterial concentrations of the open canals and sewage samples from all sites in Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves were typical of wastewater containing fecal matter, including E. coli concentrations similar to raw sewage (1 × 106 MPN per 100 mL; Figure 2, Supplemental Table 1).32 Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves demonstrated an overall annual water temperature fluctuation of less than a 10°C difference (Port-au-Prince, n = 33: 24.6–35.1°C; Gonaïves, n = 33: 27.2–35.4°C), as well as a stable, neutral pH range (Port-au-Prince: 7.3–7.8; Gonaïves, n = 15: 7.6–8.2), during the year of study (Figure 2). The particulate analysis for total dissolved solids and turbidity resulted in the Port-au-Prince sewage sampling site (MAC) having the highest median values at 2,295 ppm and 6,180 NTU (data not shown), respectively, as compared with the open water canal sites (Port-au-Prince: BDC and BNF; Gonaïves: ATP, KHF, and KSB). For detailed observations regarding the water quality analysis for all sites, refer to Supplemental Table 1 for the monthly median with lower and upper quartile data from March 2016 to February 2017.

Figure 2.

Water quality analysis from sites in Gonaïves and Port-au-Prince with illustrated physicochemical parameters and Escherichia coli concentrations for months when the data were collected (Morne à Cabri data not shown). EC = E. coli; ATP = Autorité Portuaire; KHF = Key Soleil Health Facility; KSB = Key Soleil Bridge; BDC = Bois de Chêne; BNF = Bois Neuf; TDS = total dissolved solids; ppm = parts per million; NTU = nephelometric turbidity unit.

Enterovirus detection.

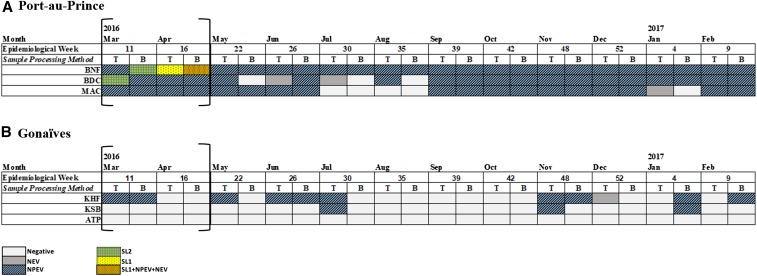

Sabin-like polioviruses were isolated from samples collected in March and April 2016 in Port-au-Prince sites (Figure 3). In March, type 2 Sabin-like PVs were isolated from a BNF sample using the BMFS and from a BDC sample using the two-phase separation method. Notably, the sample processed using the two-phase separation method isolated two type 2 Sabin-like PVs as determined from NGS. In April, type 1 Sabin-like PVs were isolated from both methods in a BNF sample. Sabin type 2 was detected prior to the switch of trivalent OPV (tOPV) to bivalent OPV (bOPV). Sequencing of the VP1 regions showed three and four nucleotide differences, respectively, from the reference Sabin strains; therefore, none of the isolates met the definition of a VDPV.33 No SL viruses were isolated from samples collected in Gonaïves (Figure 3). NPEVs were isolated from samples in 12 of 12 (100%), 11 of 12 (92%), and 9 of 12 (75%) months at the BNF, BDC, and MAC sampling sites in Port-au-Prince, respectively, by either concentration method (Figure 3). Non-polio enteroviruses were isolated from samples collected in 7 of 12 (58%) months at KHF in Gonaïves; however, they were inconsistently isolated at KSB (3 of 12 months, 25%) and none were detected at ATP (0 of 12 months, 0%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Enteroviruses isolated during March 2016 to February 2017 from six environmental surveillance sites in Haiti. No wild or vaccine-derived polioviruses were isolated. The brackets note the time period of a national mass vaccination campaign with trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (types 1, 2, and 3) targeting children aged 0–59 months. T = two-phase separation method; B = bag-mediated filtration system; NEV = non-enterovirus; NPEV = non-polio enterovirus; SL1 = Sabin-like 1; SL2 = Sabin-like 2. ATP = Autorité Portuaire; KHF = Key Soleil Health Facility; KSB = Key Soleil Bridge; BDC = Bois de Chêne; BNF = Bois Neuf; MAC = Morne á Cabri.

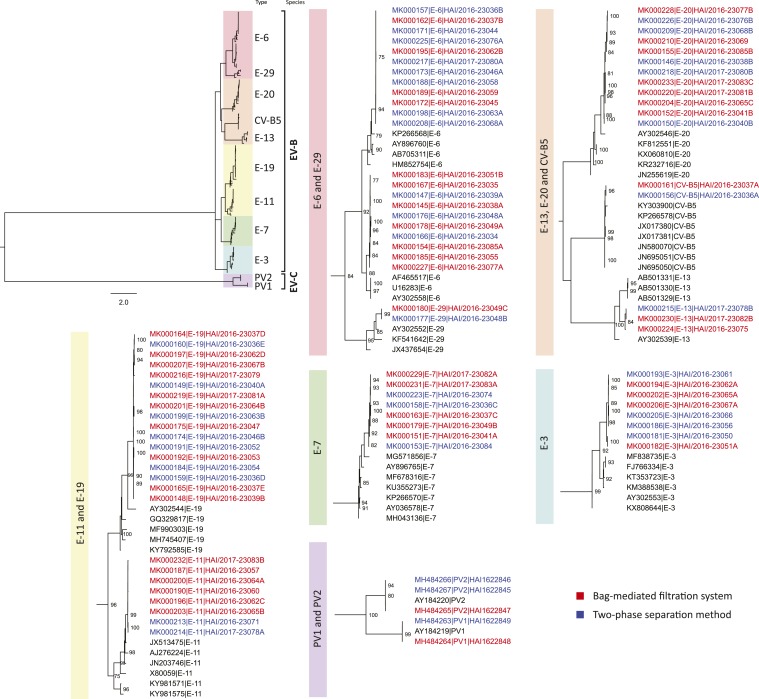

Next-generation sequencing was conducted on a subset of samples from which NPEVs were detected in the paired two-phase and BMFS samples (54 samples [24 paired samples from Port-au-Prince and three paired samples from Gonaïves]). More than 40 million reads were generated (Figure 4, Supplemental Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3). In addition, two samples from Port-au-Prince collected in March 2016 in which SL2 was detected, BNF (BMFS) and BDC (two-phase), were also sequenced by NGS. A total of 82 individual enteroviruses were sequenced: 2 coxsackievirus B5, 8 echovirus type 3 (E-3), 22 E-6, 8 E-7, 8 E-11, 3 E-13, 17 E-19, 12 E-20, and 2 E-29. At least one human NPEV was identified by NGS in 50 of the 54 (93%) samples; four samples from Port-au-Prince using two-phase method and one sample using BMFS that were positive for NPEV using the virus isolation algorithm and real-time RT-PCR had no readable sequences. The two SL2-positive samples from Port-au-Prince (BNF–BMFS and BDC–two-phase) had discordant results in their paired samples (BNF–two-phase and BDC–BMFS) that isolated E-7 and E-6 sequences, respectively. Echovirus types 6, 19, and 20 were consistently found, with at least one of these detected each month (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 4.

Enterovirus VP1 phylogeny of viruses detected through environmental surveillance in Haiti using two different processing methods. Sequences obtained from viruses isolated after the bag-mediated filtration system are listed in red text, and after the two-phase separation method are listed in blue text. Representative GenBank references are listed in black text. A broad-perspective tree is displayed on the top left, whereas the detailed clade-level trees present NPEV sequence accession number, type, and strain name. CV = Coxsackievirus; EV = Enterovirus; E = Echovirus; PV = Poliovirus.

Method comparison.

A total of 36 method sample pairs (each from Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves, for 72 samples total) were available for comparison of the two-phase separation method and the BMFS. The two-phase method concentrated a set volume of 500 mL. The BMFS concentrated a median of 1,250 mL (min = 748 mL, max = 1,440 mL). The final concentrate volume for the two-phase separation method and BMFS averaged 14.8 and 15.0 mL, respectively. Thus, the concentration factors for the two-phase separation method and BMFS were 33.9 and 83.3, respectively. Concordance between methods for detecting or not detecting any enterovirus occurred in 62 of 72 samples; 30 were paired negative results (Table 1). There was no statistical difference between the two methods for the detection of any enterovirus (mid-P-value = 0.55). The sensitivity of BMFS for the detection of any enterovirus compared with the “gold standard” method (e.g., two-phase separation method) was 84% (70–93%). The specificity of BMFS for the detection of any enterovirus compared with two-phase separation was 88% (73–95%). There was no statistical difference between the two methods for the detection of Sabin-like PV (mid-P-value = 0.75), but the number of detections was very low for both methods (Table 2). The same number of enteroviruses was found in 14 of 27 (51.9%) paired samples by the two concentration methods, and NGS identified similar enterovirus types in 16 of the 27 paired samples (59.3%) (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). In eight of the paired samples, the BMFS found at least one more type of enterovirus, whereas in two paired samples, the two-phase method found one more enterovirus type (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Comparison of the two-phase separation method and bag-mediated filtration system (BMFS), sensitivity, and specificity for the isolation of any enterovirus as determined by the exact McNemar’s test, where statistical significance was mid-P-value < 0.05

| Positive two-phase separation | Negative two-phase separation | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive BMFS | 32 | 4 | 36 |

| Negative BMFS | 6 | 30 | 36 |

| Total | 38 | 34 | 72 |

BMFS = bag-mediated filtration system. mid-P-value = 0.55. Sensitivity (CI) = 84% (70–93%). Specificity (CI) = 88% (73–95%).

Table 2.

Comparison of the two-phase separation and bag-mediated filtration system (BMFS) methods and specificity for the isolation of Sabin-like poliovirus as determined by the exact McNemar’s test, where statistical significance was mid-P-value < 0.05

| Positive two-phase separation | Negative two-phase separation | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive BMFS | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Negative BMFS | 1 | 69 | 70 |

| Total | 2 | 70 | 72 |

BMFS = bag-mediated filtration system. mid-P-value = 0.75. Specificity (CI) = 99% (92–100%).

DISCUSSION

Poliovirus environmental surveillance was established in two cities in Haiti to complement AFP surveillance in populations considered to be at risk for VDPV emergence, as well as WPV importation and circulation. Open canals and a wastewater treatment plant were sampled in lieu of a structured sewer network. The limited detection of SL PVs to confirm the sensitivity of the sites to detect PV, whether due to catchment population or low vaccine coverage, provided an opportunity to evaluate the use of NPEVs as a PV surrogate. In addition, the evaluation of two concentration methods and additional water quality analysis during the first year of surveillance provided an opportunity to improve environmental surveillance knowledge, to define criteria for appropriate environmental sampling sites, and to improve the overall viral surveillance knowledge by characterizing detected NPEVs.

During March 2016–February 2017, no WPVs or VDPVs were detected at any site with either concentration method. Sabin type 2 was detected in Port-au-Prince in samples collected in March 2016 at the BNF and BDC sites, using the BMFS and two-phase concentration methods, respectively. Sabin type 1 was found using both methods in April 2016 at the BNF site. These detections coincided with Haiti’s final national tOPV (serotypes 1, 2, and 3) vaccination campaigns before global cessation of tOPV use and the switch to bOPV (serotypes 1 and 3).34,35 The lack of PV detection, even Sabin strains, for the remainder of the year raises the question of whether the vaccine coverage was sufficient for detection, as well as a variety of other factors that would impact virus detection in the environment (e.g., sanitary management practices of human fecal waste and population density). Other countries, such as Angola, Cameroon, and Chad, have had similar low Sabin strain detection in environmental surveillance, except around the time of mass polio vaccination campaigns.36

Non-polio enteroviruses were isolated in 75–100% of all the samples, by either processing method during the reporting period for the three sites in Port-au-Prince. Further analysis of 24 paired samples in Port-au-Prince using NGS confirmed the detection of a number of NPEVs, primarily echoviruses. The bias for the detection of echoviruses and other species B enteroviruses was most likely due to the RD cell line being used as part of the WHO virus isolation algorithm.37 Environmental surveillance studies in Northern Italy and North India isolated mainly Enterovirus B types (e.g., Coxsackie B viruses and echoviruses),38,39 whereas studies that included an additional cell line beyond RD cells (e.g., HEp2 and HT29) isolated a wider variety of enteroviruses.16,40 The detection of human NPEVs confirms that the selected sites are impacted by human sewage. In Gonaïves, only the KHF site met this NPEV positive isolation criterion (greater than or equal to 50% for over a 6-month period), with NPEVs being isolated from 75% of samples, of which three paired samples analyzed by NGS yielded echoviruses 3, 6, and 11. Subsequently, the sites in Gonaïves have been reviewed and new sites investigated, emphasizing that the establishment of environmental surveillance is a dynamic process that can take many months, and, once established, requires continuous monitoring for quality and sensitivity. NPEV detection in samples provides a dependable proxy for PVs and for environmental surveillance site sensitivity, as polioviruses and the NPEVs have similar structure, stability, and survival characteristics. For a given environmental surveillance sampling site to be considered sufficiently sensitive, the NPEV positive isolation rate should be ≥ 50% for over a 6-month period (M. Steven Oberste–personal communication).

Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves monthly averages for rainfall from March 2016 to December 2016 (2017 data not available) shifted from typical “wet” and “dry” months, where April to June and October and November are months typically with higher rainfall averages. Port-au-Prince experienced higher rainfall averages from March to May (average 348 mm) and August to November (196 mm) than from June to July (89 mm) and December (16 mm), whereas Gonaïves experienced higher rainfall averages from March to May (average 228 mm) and August to November (202 mm) than from June to July (72 mm) and December (46 mm).21 The fluctuations in rainfall did not illustrate an impact water quality parameters. Based on the water quality criteria developed by various international agencies, the pH ranges of all Haiti sampling sites were technically of adequate quality (6.5 to 8.5), but the temperature was greater than the acceptable range for drinking (25°C).41 The turbidity and total dissolved solids levels were reflective of surface waters, whereas the total coliform and E. coli concentrations were beyond recreational limits41 and within the ranges found in sewage and wastewater.32 Thus, the Haiti environmental samples were consistent with general surface water quality characterizations that suggest minimal external industrial influences, beyond the fecal matter contributions, that would potentially impact virus survival and/or detection. Such water quality analyses provided additional confirmation of fecal influence because the sampling sites were not part of an established sewer network. Although this suite of water quality analyses are not included in the WHO protocol for the establishment or monitoring of environmental surveillance sites, their use in Haiti served to confirm the presence of sewage and could be useful in site reselection in the event no polioviruses or NPEVs were detected.

As part of increasing the effectiveness of environmental surveillance, an alternative concentration method (BMFS) to the two-phase separation method was evaluated and no significant difference between the methods was found based on the enterovirus isolation (Table 1, mid-P-value = 0.55). A higher number of NPEV types was detected by BMFS (46 types; Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3), possibly explained by BMFS’s higher concentration factor (83.33), than by two-phase separation (33.90) because of higher starting volume and the additional secondary concentration step. Nevertheless, the difference was not significant. Although each method is effective in concentrating samples to isolate PV and other enteroviruses, the technical approach is different. The two-phase separation method, a type of “aqueous two-phase system,” was developed by Norrby and Albertsson as a simple way to concentrate PV while maintaining the integrity and infectivity of the viral particle.42 This method uses physicochemical properties of the agent and/or solutes to partition the polymers (polyethylene glycol and dextran) into separate two aqueous phases, where hydrophobicity, surface charge, concentration, size, and bioaffinity play a major role in partitioning the virus between the two phases.43 The BMFS uses an electropositive charged filter that adsorbs viruses and particulates with negative charges; the adsorbed viruses are thereafter eluted from the filter. Future PV environmental surveillance projects will evaluate other concentration methods.

Increasing environmental surveillance effectiveness is a key goal of the environmental surveillance expansion plan and implementing PV environmental surveillance in a country with no established sewer network provided an opportunity to find solutions to limitations.11 The main limitation in Haiti was that no prior data were available for the identified sampling sites regarding human viruses and sewage contributions. Although the biological and physicochemical water parameters could not differentiate between human or animal waste, the E. coli concentrations confirmed the presence of fecal material. Another limitation was catchment population relative to the target population size of 100,000 to 300,000 specified in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative environmental surveillance guidelines.19 Gonaïves was included in the sampling because it is the second most populous city in Haiti, despite not having the minimal recommended population. In addition, the collection times for Gonaïves sites and the Port-au-Prince MAC site were not always consistent with the recommendation of collecting samples during the morning flow period (before 9 am) because of logistics issues.19 Thus, peak morning flushing of sewage and any associated polioviruses may have been missed. Lessons learned in establishing environmental surveillance in Port-au-Prince and Gonaives have been useful for establishing sites in Cap Haitien and Saint Marc. Another limitation was when MAC samples consisted of thick sludge and large particulates, posing a challenge for both the two-phase separation method and the BMFS. As enteroviruses are charged and have an affinity to attach to particles, the detection rate may have been higher if such particulates could have been processed.

As global polio eradication nears and VDPVs continue to emerge and circulate, environmental surveillance has become a critical adjunct to AFP surveillance. Environmental surveillance for polioviruses in Haiti was successfully established in three sampling sites in each of Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves. The experience of 1 calendar year of sampling has informed the appropriateness of the initially chosen sampling sites, importance of careful monitoring of an adequate PV surrogate, and robustness of two processing methods. Alternative sampling sites in Haiti will be investigated to replace those not meeting performance standards for the continuing years of environmental surveillance.

Supplemental tables and figure

Acknowledgments:

We thank our CDC laboratory colleagues Naomi Dybdahl-Sissoko and Hong Pang for their assistance in cell line management, Elizabeth Henderson for guidance regarding sample and database management, Nancy Gerloff for sharing her molecular knowledge, Claire Capshew for her assistance in preparing the field protocols and supplies, and Steve Oberste for his expertise and review of the manuscript. We appreciate the maps produced by Yoann Mira, Mark Staples, and Philippe Veltsos from Novel-T Sàrl from the environmental surveillance map catalogue (http://maps.novel-t.ch): sponsored and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with special thanks to Vincent Seaman and to Blair-Freese. We also extend our appreciation to our University of Washington colleagues who developed the BMFS, including J. Scott Meschke, Jeffry Shirai, Nicola Beck, Alexandra Kossik, Nicolette Zhou, and Christine Fagnant-Sperati, for their continued feedback and guidance on BMFS. We thank the Ministry of Public Health and Population Haiti for its collaboration and Marie Jose Laraque for her assistance with shipping samples to Atlanta. We thank Howard Gary, formerly of the Global Immunization Division (GID), CDC-Atlanta, for the initial conception of the protocol. We also thank Kathleen Wannemuehler and Kotwoallama “Reine” Zerbo from GID for their statistical expertise.

Note: Supplemental tables and figure appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kew O, 2014. Enteroviruses. Kaslow RA, Stanberry LR, Le Duc JW, eds. Viral Infections of Humans. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO , 1988. Global Eradication of Poliomyelitis by the Year 2000. Geneva, Switzerland: Forty-first World Health Assembly. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan F, Datta Deblina S, Quddus A, Vertefeuille JF, Burns CC, Jorba J, Wassilak SG, 2018. Progress toward polio eradication—worldwide, January 2016–March 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 524–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC , 1995. Progress toward global poliomyelitis eradication, 1985–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 44: 273–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Quadros CA, Andrus JK, Olive J-M, de Macedo CG, Henderson DA, 1992. Polio eradication from the western hemisphere. Annu Rev Public Health 13: 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins FC, de Quadros CA, 1997. Certification of the eradication of indigenous transmission of wild poliovirus in the Americas. J Infect Dis 175 (Suppl 1): S281–S285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC , 2000. Public health dispatch: outbreak of poliomyelitis – Dominican republic and Haiti, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 49: 1094–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinje J, et al. 2004. Isolation and characterization of circulating Type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus from sewage and stream waters in Hsipaniola. J Infect Dis 189: 1168–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO , 2013. Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013–2018. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 10.PAHO , 2014. Report from the Technical Advisory Group on Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, XXII Meeting. Washington, DC: PAHO. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO , 2015. Polio Environmental Surveillance Expansion Plan–Global Expansion Plan under the Endgame Strategy 2013–2018. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hovi T, et al. 2005. Environmental surveillance of wild poliovirus circulation in Egypt—balancing between detection sensitivity and workload. J Virol Methods 126: 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hovi T, Stenvik M, Partanen H, Kangas A, 2001. Poliovirus surveillance by examining sewage specimens. Quantitative recovery of virus after introduction into sewerage at remote upstream location. Epidemiol Infect 127: 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poyry T, Stenvik M, Hovi T, 1988. Viruses in sewage waters during and after a poliomyelitis outbreak and subsequent nationwide oral poliovirus vaccination campaign in Finland. Appl Environ Microbiol 54: 371–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esteves-Jaramillo A, et al. 2014. Detection of vaccine-derived polioviruses in Mexico using environmental surveillance. J Infect Dis 210 (Suppl 1): S315–S323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndiaye AK, Diop PA, Diop OM, 2014. Environmental surveillance of poliovirus and non-polio enterovirus in urban sewage in Dakar, Senegal (2007–2013). Pan Afr Med J 19: 243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou NA, Fagnant CS, Shirai JH, Sharif S, Zaidi S, Rehman L, 2018. Evaluation of the bag-mediated filtration system as a novel tool for poliovirus environmental surveillance: results from a comparative field study in Pakistan. PLoS One 13: e0200551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estivariz CF, Placeholder O, 2019. Poliovirus environmental surveillance in Mexico: comparison of two-phase and BMFS methods. Food Environ Virol, Accepted. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO , 2015. Global Polio Eradication Initiative: Guidelines on Environmental Surveillance for Detection of Polioviruses, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novel-t, PATH , Environmental Surveillance, Supporting Polio Eradication. Available at: https://www.es.world/#!/catalog. Accessed September 9, 2019.

- 21.World Bank Group , 2019. Climate Change Knowledge Portal. Available at: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/. Accessed April 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fagnant CS, Beck NK, Yang M-F, Barnes KS, Boyle DS, Meschke JS, 2014. Development of a novel bag-mediated filtration system for environmental recovery of poliovirus. J Water Health 12: 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagnant CS, et al. 2017. Improvement of the bag-mediated filtration system for sampling wastewater and wastewater-impacted waters. Food Environ Virol 10: 72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerloff N, et al. 2018. Diagnostic assay development for poliovirus eradication. J Clin Microbiol 56: e01624–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montmayeur AM, et al. 2017. High-throughput next-generation sequencing of polioviruses. J Clinical Microbiol 55: 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng TFF, Kondov NO, Deng X, Van Eenennaam A, Neibergs HL, Delwart E, 2015. A metagenomics and case-control study to identify viruses associated with bovine respiratory disease. J Virol 89: 5340–5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katoh K, Standley DM, 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burns CC, Kilpatrick DR, Iber JC, Chen Q, Kew OM, 2016. Molecular properties of poliovirus isolates: nucleotide sequence analysis, typing by PCR and real-time RT-PCR. Martín J, ed. Poliovirus: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer, 177–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilpatrick DR, et al. 2011. Poliovirus serotype-specific VP1 sequencing primers. J Virol Methods 174: 128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stamatakis A, 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNemar Q, 1947. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika 12: 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tchobanoglous G, Burton FL, Stensel HD, 2003. Wastewater Engineering–Treatment and Reuse. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns CC, Diop OM, Sutter RW, Kew OM, 2014. Vaccine-derived polioviruses. J Infect Dis 210 (Suppl 1): S283–S293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hampton LM, et al. 2016. Cessation of trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine and introduction of inactivated poliovirus vaccine—worldwide, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65: 934–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diop OM, Asghar H, Gavrilin E, Moeletsi NG, Rey Benito G, Paladin F, Pattamadilok S, Zhang Y, Goel A, Quddus A, 2017. Virologic monitoring of poliovirus type 2 after oral poliovirus vaccine type 2 withdrawal in April 2016–worldwide, 2016–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66: 530–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO , 2018. Mise a jour hedbomadaire sur l’Initiative d’Eradication de la Polio en Afrique Centrale (Weekly Update for the Polio Eradication Initiative in Central Africa). Libreville, Gabon: Intercountry Support Team for Central Africa. World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO , 2004. Polio Laboratory Manual. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pellegrinelli L, Bubba L, Primache V, Pariani E, Battistone A, Delogu R, Fiore S, Binda S, 2017. Surveillance of poliomyelitis in Northern Italy: results of acute flaccid paralysis surveillance and environmental surveillance, 2012–2015. Hum Vaccin Immunother 13: 332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiwari S, Dhole TN, 2018. Assessment of enteroviruses from sewage water and clinical samples during eradication phase of polio in North India. Virol J 15: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benschop KSM, van der Avoort HG, Jusic E, Vennema H, van Binnendijk R, Duizer E, 2017. Polio and measles down the drain: environmental enterovirus surveillance in The Netherlands, 2005 to 2015. Appl Environ Microbiol 83: e00558–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sargaonkar A, Deshpande V, 2003. Development of an overall index of pollution for surface water based on a general classification scheme in Indian context. Environ Monit Assess 89: 43–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norrby ECJ, Albertsson PA, 1960. Concentration of poliovirus by an aqueous polymer two-phase system. Nature 188: 1047–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asenjo JA, Andrews BA, 2011. Aqueous two-phase systems for protein separation: a perspective. J Chromatogr 1218: 8826–8835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.