Abstract

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are at risk for poor couple relationship quality. The goal of the current study was to understand actor and partner associations between daily level of parenting stress and perceived couple interactions using a 14-day daily diary in 186 families of children with ASD. A comparison group of 182 families of children without a neurodevelopmental disability was included to determine if actor and partner associations differed in a context of child ASD. On each day of the 14-day diary, parents independently rated their daily level of parenting stress (7-point scale) and reported on the perceived presence of different types of positive (e.g., hugged and kissed) and negative (e.g., critical comment) couple interactions. Multilevel models were used to examine actor and partner effects, and their interaction, in mothers and fathers and by group (ASD versus comparison). Results indicated that actor daily level of parenting stress negatively co-varied with perceived positive couple interactions in mothers in both groups. In contrast, actor daily level of parenting stress positively co-varied with perceived positive couple interactions in fathers in the ASD group. There was a significant interaction between actor and partner daily level of parenting stress for perceived negative couple interactions in both mothers and fathers. Specifically, one’s own daily level of parenting stress was more strongly positively related to her/his perceived negative couple interactions on days when her/his partner also had high parenting stress. This interaction was stronger in mothers in the ASD versus comparison group. Implications for family interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Autism, Marital, Couple, Parenting Stress, Partner

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disability currently estimated to occur in 1 in 58 children in the U.S. (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018). Children with ASD evidence social communication impairments, sensory sensitivities, and restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychological Association, 2013), as well as co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., Choi & Kovshoff, 2013). This profile of ASD symptoms and co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems, and especially externalizing behavior problems, is associated with an elevated level of parenting stress in mothers and fathers (Estes et al., 2013; Lecavalier, Leone, & Wiltz, 2006). Parents of children with ASD have also been shown to be at risk for poor couple relationship outcomes including more dissatisfying and conflictual couple relationships (e.g., Gau et al., 2012; Hartley et al., 2017) and an increased risk of divorce (Berg, Cheng-Shi, Acharya, Stolbach, & Msall, 2016; Hartley et al., 2010) relative to peers who have children without disabilities. Studies have examined the link between one’s own level of parenting stress and perceived couple relationship experiences in parents of children with ASD (e.g., Hartley, Barker, Baker, Seltzer, & Greenberg, 2012; Lickenbrock, Ekas, & Whitman, 2011). However, virtually nothing is known about cross-partner associations between daily level of stress and perceived couple interaction experiences in families of children with ASD, or the extent to which partners may mitigate or exacerbate the link between one’s own daily level of parenting stress and perceived couple relationship experiences. We examined these questions using a 14-day daily diary with 186 families of children with ASD and a comparison group of 182 families of children without disabilities.

The family systems perspective posits that the experiences of individuals and subsystems within a family are interdependent and interrelated (e.g., Fine & Finchman, 2013). Within this perspective, stressful parenting experiences are expected to be associated with stressful couple relationship experiences in mutually reinforcing bidirectional ways. Specifically, within a stress spillover hypothesis, negative affect and tension originating in one family domain (e.g., parenting domain) carries into other domains (e.g., couple domain), creating a succession of negative and frustrating experiences (e.g., Cox, Paley, & Harter, 2001). Research examining non-parenting stressors (e.g., financial or work stress) suggests that when stressed, individuals engage in fewer positive couple interactions such as offering support and positive affect (Neff & Karney, 2004), and more negative couple interactions such as avoiding her/his partner and argumentative communication (e.g., Jackson et al., 2016). Moreover, when individuals experience higher stress than is typical, they have been found to use a maladaptive attributional style in which they are more likely to blame their partner for couple problems (Neff & Karney, 2004). Thus, when stressed, individuals may both engage in fewer positive and more negative couple interactions, and interpret partner behaviors in a negative way.

In line with the stress spillover hypothesis, parents in a context of high child-related challenges report more dissatisfying and lower quality couple relationships. For example, parents of children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been found to use more maladaptive and argumentative communication (Sochos & Yahya, 2015) and to have an increased risk for divorce (Wymbs et al., 2008) relative to parents of children without ADHD. Similarly, child externalizing behavior problems have been found to predict increased couple conflict across time in samples of parents from the general population (e.g., Schermerhorn, Cummings, DeCarlo, & Davies, 2007). Parents of children with ASD have similarly been found to report lower couple relationship satisfaction or quality (e.g. Gau et al., 2012), more frequent, severe and unresolved couple conflicts (Hartley et al., 2017), and a higher rate of divorce (e.g., Hartley et al., 2010) than parents of children without a neurodevelopmental disability. Moreover, research has examined the association between one’s own level of parenting stress and his/her perceived couple relationship quality in the context of child ASD. Parents of children with ASD who reported a higher global level of parenting stress also reported lower global couple relationship quality (Langley, Totsika, & Hastings, 2017). In addition, experiencing a day with a high level of parenting stress predicted perceiving fewer positive couple interactions (e.g., meaningful conversations with partner) the next day in mothers, but not fathers, of children with ASD (Hartley, Papp, & Bolt, 2016). Thus, actor (i.e., one’s own) stress from parenting appears to spillover into couple interactions in the context of child ASD.

According to the family systems perspective, however, stress spillover between the parenting and couple domain is best understood when jointly considering both parents in the family system (Fine & Finchman, 2013). Stress crossover effects are expected to occur where stress in one partner influences the couple relationship experiences of the other partner within interdependent relationships (e.g. Falconier, Nussbeck, Bodenmann, Schneider, & Bradbury, 2015; Neff & Karney, 2007). To date, crossover research has focused on the direct effect of partner (i.e., one’s partner’s) level of stress on the actor (one’s own) perceived couple relationship experiences in samples based on the general population. Across these studies, having a partner with a high level of stress was associated with actor subjective ratings of a lower quality couple relationship (e.g., feeling less positive about the relationship) (e.g., Falconier et al., 2015; Neff & Karney, 2004; Randall & Bodenmann, 2017; Thompson & Bolger, 1999). For example, in a longitudinal study of 139 newly married couples, on occasions when one’s partner reported a relatively higher level of stress, the actor reported being less satisfied with the marriage (Neff & Karney, 2007). Similarly, in a daily diary study, on days that one’s partner reported a more depressed mood, the actor was less positive about the couple relationship (Thompson & Bolger, 1999). Such crossover effects may also occur in couples who have a child with ASD, such that partner daily level of parenting stress may co-vary from one-day-to-the-next with actor subjective perceptions of daily positive and negative couple interactions.

In addition to a direct crossover effect, it is possible that stress in one’s partner moderates the impact of one’s own stress on her/his perceived positive and negative couple interactions. However, this pathway has received much less research attention. Within couples who have a child with ASD, having a partner with a low level of parenting stress may mitigate the negative impact of one’s own stressful parenting day on her/his perceived couple interactions; the non-stressed partner may offer support and warmth to the stressed partner or thwart potential couple arguments by ‘letting things go’. Indeed, there is evidence that individuals who are generally satisfied with their couple relationship reframe their partner’s occasional negative behavior (e.g., attribute the negative behavior to a stressful day) in order to maintain a positive couple relationship (e.g., Neff & Karney, 2004). For example, among newlyweds, Neff and Karney (2007) found that wives’ level of stress was not associated with lower marital satisfaction on occasions when husbands’ had a relatively low level of stress. In contrast, having a partner who is also experiencing a high level of parenting stress may exacerbate the impact of one’s own high level of parenting stress on her/his perceived positive and negative couple interactions. When both partners experience a high parenting stress day, a cycle of escalating maladaptive couple interactions may occur in which both partners reciprocate negative couple interactions as they blame partners for couple problems (Neff & Karney, 2004). In support of this idea, there is evidence that when individuals report a high level of stress they were more likely to reciprocate the negative behaviors of her/his partner (Sears, Repetti, Reynolds, Robles, & Krull, 2016). Thus, an escalating pattern of negative couple interactions may occur on days that both parents of children with ASD in a couple experience a high level of parenting stress.

Partner Stress in ASD versus Comparison Families

In studies on the general population, acute stress (i.e., stress from short-term and immediate stressors) spillover between family domains was found to be more prominent when individuals were in a context of a chronic stressor (i.e., ongoing stressor) (e.g., Almeida, Wethington, & Chandler, 1999; Karney, Story, & Bradbury, 2005). When faced with ongoing stressors, individuals have been posited to have limited psychological resources (i.e. motivation and energy to stay optimistic and regulate emotions and thoughts in adaptive ways) for dealing with an added acute stressor or day that was particularly stressful (DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1988; Jackson et al., 2016; Karney, Story, & Bradbury, 2005). Indeed, experiencing an acute stressor or high stress day has been found to take the greatest toll on the mood, health, and interpersonal relationships of individuals undergoing chronic stressors including those who are part of a stigmatized/marginalized group, have low household income, or have a health condition (DeLongis et al., 1988; Jackson et al., 2016; Karney, Story, & Bradbury, 2005). For example, in a sample of 172 newly wed couples, wives who were experiencing chronic stressors (i.e., ongoing stressful interpersonal relationships or financial, work, or health stressors) were more reactive to acute stressors (e.g., short-term problems such as meeting a deadline) resulting in more negative perceptions of their couple relationship than were wives not undergoing chronic stressors (Neff & Karney, 2004). There is also evidence that the crossover effect of partner level of acute daily stress on actor daily mood is stronger if the actor is undergoing a chronic stressor (Larson & Almeida, 1999; Neff & Karney, 2007). Within interdependent dyadic relationships, such as the couple relationship or parent-child relationship, daily diary studies have found that individuals undergoing chronic stress were most strongly influenced by his/her partner’s negative mood and negative couple interactions (Neff & Karney, 2005; Neff & Karney, 2007). Thus, given the context of chronically high parenting stress associated with child ASD (e.g., Estes et al., 2013), these parents may be more strongly influenced by having a partner experience a high stress day (via both direct and moderating pathways) relative to parents of children without neurodevelopmental disabilities.

Gender and Partner Stress

In studies on the general population, the impact of partner stress on actor couple relationship experiences has been found to vary by gender. Specifically, partner level of stress has been shown to be more strongly associated with actor couple relationship experiences in men than in women (e.g., Falconier et al., 2015; Neff & Karney, 2007). Reasons for this difference have been theorized to stem from women being more likely to explicitly communicate about their stress to their partner; as a result, when women have a high level of stress, it may impact both partners in the couple more than when men have a high level of stress (Falconier et al., 2015; Neff & Karney, 2005). Moreover, men have been found to respond in less supportive ways when partners are stressed than women (Neff & Karney, 2005); thus, a high level of stress in women (as compared to men) may lead to more maladaptive couple interactions. For instance, men have been found to use criticism and partner blaming in response to partner stress, while women offer more support and warmth than men (Neff & Karney, 2005). It is unclear if a similar pattern of gender differences occurs in the context of child ASD.

Current Study

The goal of the current study was to determine if: 1) partner daily level of parenting stress was associated with actor perceived positive and negative couple interactions; 2) partner daily level of parenting stress moderated the association between actor daily level of parenting stress and her/his perceived positive and negative couple interactions; and 3) the above associations differed for couples who have a child with ASD as compared to couples who have a child without neurodevelopmental disabilities and by parent gender. These associations were examined at a within-couple level using a 14-day daily diary in a sample of 186 couples who had a child with ASD and comparison group of 182 couples who had a child without a neurodevelopmental disability. On each day of the 14-day diary, parents independently rated their subjective level of daily parenting stress (7-point scale) and reported on their subjective perception of the number of types of positive (e.g., had a meaningful conversation or hugged and kissed) and negative (e.g., avoided, ignored, or made a critical comment) couple interactions they had, each ranging from 0 to 8. Perceived positive couple interactions and perceived negative couple interactions were examined separately based on evidence that these are unique dimensions, each with their own contribution to couple relationship satisfaction or quality (e.g., Boerner, Jopp, Carr, Sosinsky, & Kim, 2014), and that both are influenced by partner level of stress (e.g., Neff & Karney, 2004).

We hypothesized that partner daily level of parenting stress would be related to actor perceived number of types of positive and negative couple interactions, in negative and positive directions respectively. Partner daily level of parenting stress was also predicted to moderate the association between actor daily level of parenting stress and actor perceived number of types of positive and negative couple interactions. Specifically, actor daily level of parenting stress was expected to be more strongly positively associated with her/his perception of maladaptive couple interactions (i.e., fewer perceived positive and more negative) when her/his partner also experienced a day with a high level of parenting stress. We hypothesized that the above associations would be stronger in the ASD group than in the comparison group, given previous evidence that acute stress crossover is more likely in a context of chronic high stress (e.g., Karney et al., 2005; Neff & Karney, 2007). Finally, we hypothesized that for both groups (ASD and comparison), partner daily level of parenting stress would be more strongly associated with actor perceived number of types of positive and negative couple interactions in fathers than in mothers. This hypothesis was based on findings on the general population that women discuss their stress more often with partners than men and women are less likely to be supported by their partners when stressed compared to men (Falconier et al., 2015; Neff & Karney, 2005).

Methods

Participants

Participants were involved in a longitudinal study, approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board, originally including 197 couples who had a child with ASD and a comparison group of 182 couples who had a child without a neurodevelopmental disability. Analyses focused on data collected at Time 1. Families were recruited through research registries, fliers posted at ASD clinics, community settings, and school mailings. Target children in both groups (ASD and comparison) were aged 5–12 years. Couples had to be in a committed, long-standing relationship (≥ 3 years). If couples had more than one child with ASD, the eldest was the target child to capture the first ASD parenting experience. Diagnosis of ASD was confirmed using educational or medical records; the Autism Diagnosis Observation Schedule (Gotham, Risi, Pickles, & Lord, 2006) had to have been used in the diagnostic assessment. The Social Responsiveness Scale-Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012) was completed by parents to confirm an elevated level of ASD symptoms. In the ASD group, five children had a total SRS-2 T-score < 60 and were excluded from analyses. In the comparison group, screening questions were used to ensure that couples did not have any children diagnosed with or suspected to have a neurodevelopmental disability, nor had any children received special education or birth-to-3 early intervention services. Eight target children in the comparison group had a total SRS-2 T-score ≥ 60, and were removed from analyses. An additional six families in the ASD group did not complete the 14-day daily diary.

Table 1 displays socio-demographics for the 186 families in the ASD group and 174 families in the comparison group included in analyses. Independent sample t-tests and chi-square statistics indicated no significant group differences in parent age, race/ethnicity, family size, or child age or gender. The ASD group had significantly lower maternal education and household income than the comparison group. Maternal education and household income were controlled in analyses. It is possible that group differences reflect mothers in the ASD group selecting out of higher education and paid employment due to heightened childcare demands in line with previous studies (e.g., Leiter, Krauss, Anderson, & Wells, 2004). Indeed, ASD group mothers reported fewer weekday hours (M = 9.12, SD = 3.11) in paid employment than comparison group mothers (M=10.89, SD = 3.04), t (358) = 5.46,p <.01.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics for the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Comparison Group

| ASD Group (N = 186) |

Comparison Group (N= 174) |

t value, f value or χ2, p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | |||

| Age (M[SD]) | 38.48 (5.50) | 38.80 (5.78) | t (358) = −0.54, p = .59 |

| Education (N[%]) | χ2 (5, 354) = 11.91, p = 04 | ||

| No HS degree | 4 (2.2%) | 4 (2.3%) | |

| HS degree or equivalent | 11 (5.9%) | 10 (5.7%) | |

| Some college | 35 (l8.8%) | 19 (10.9%) | |

| Associate’s or Bachelor’s | 88 (47.3%) | 69 (39.6%) | |

| Some graduate school | 11 (5.9%) | 13 (7.5%) | |

| Graduate degree | 37 (19.9%) | 59 (33.9%) | |

| Daily Level of Parenting Stress (M[SD]) | 2.45 (1.10) | 1.48 (0.69) | F (1, 358) = 10.46, p < |

| Daily Positive Couple Interactions | 2.85 (1.88) | 3.46 (1.95) | .001 |

| (M[SD]) | 0.95 (1.35) | 0.83 (1.21) | F (1, 358) = 3.68, p < .001 |

| Daily Negative Couple Interactions | F (1, 358) = 1.21, p = .23 | ||

| (M[SD]) | |||

| Father | |||

| Age (M[SD]) | 40.67 (6.19) | 40.50 (6.50) | t (358) = 0.25, p = .80 |

| Education (N[%]) | χ2 (5, 354) = 7.74, p = .17 | ||

| No HS degree | 10 (5.4%) | 4 (2.3%) | |

| HS degree or equivalent | 22 (11.8%) | 14 (7.5%) | |

| Some college | 28 (15.1%) | 23 (13.8%) | |

| Associate’s or Bachelor’s | 82 (44.1%) | 77 (44.3%) | |

| Some graduate school | 11 (5.9%) | 8 (4.6%) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 33 (17.8%) | 48 (27.6%) | |

| Daily Level of Parenting Stress (M[SD]) | 1.99 (0.88) | 1.43 (0.57) | F (1, 358) = 6.96, p < .001 |

| Daily Positive Couple Interactions | 3.28 (1.39) | 3.60 (1.34) | F (1, 358) = −3.39, p < |

| (M[SD]) | 0.77 (0.69) | 0.68 (0.68) | .001 |

| Daily Negative Couple Interactions | F (1, 358) = 0.14, p = .90 | ||

| (M[SD]) | |||

| Couple | |||

| Household income (M[SD]) | 9.09 (3.19) | 10.66 (2.83) | t (358) = −4.92, p < .01 |

| Couple relationship length (m[SD]) | 11.22 (5.15) | 11.93 (4.61) | t (358) = −1.43, p = .15 |

| Target Child | |||

| Race/Ethnicity (N[%]) | χ2 (6, 353) = 1.17, p = .98 | ||

| White, Non-Latino | 138 (74.2%) | 134 | |

| Latino | 21 (25.8%) | (73.0%) | |

| Asian | 8 (4.3%) | 20 (23.0%) | |

| American Indian | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (4.0%) | |

| Pacific Islander | 4 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Black | 6 (3.2%) | 4 (2.3%) | |

| Multiple ethnicities | 7 (3.8%) | 7 (4.0%) | |

| 6 (3.4%) | |||

| Age (M[SD]) | 7.88 (2.3) | 7.94 (2.4) | t (358) = −0.24, p = .81 |

| Gender (N[%]) | |||

| Male | 154 (86.5%) | 146 (83.9%) | χ2(1, 359) = 1.06, p < .55 |

| Female | 24 (13.5%) | 28 (16.1%) | |

| ID (N[%]) | 64 (35.4%) | 0 (0%) | χ2 (1, 359) = 75.01, p < |

| .01 | |||

| SRS-2 (M[SD]) | 77.69 (10.99) | 49.94 (8.34) | t (358) = 26.85, p < .01 |

Note. HS = High school. ID = Intellectual Disability. SRS-2 = Social Responsiveness Scale Second Edition.

Procedure

Parents independently completed a 14-day daily diary (about 10 mins/day) via secured online surveys or using an iPod touch that did not require internet connection. Parents within each couple were instructed to complete diary entries at the same designated time (which they chose) each day. Parents were sent a reminder email 30 minutes prior to this time each day.

Measurements

Socio-demographics.

Family socio-demographics were reported on by parents and included in analyses to control for group (i.e., ASD versus comparison) differences and the effect of these variables on perceived positive and negative couple interactions. Parent education was coded: 0 = less than high school degree, 1 = high school diploma or General Equivalency Diploma, 2 = some college, 3 = college degree, 4 = some graduate school, and 5 = graduate/ professional degree. Length of couple relationship was based on start of the relationship and coded in years. Target child age was coded in years. Household income was coded from 0 ($1 - $9,999) to 13 ($160,000 +), increasing by $10 to $20K intervals.

Daily level of parenting stress.

Daily level of parenting stress was assessed by a single item, “Did you feel stressed by the caregiving activities related to your son or daughter?”, rated 1 (No) to 7 (Yes, Extremely) in reference to the past 24 hours. In the current sample, the mean daily level of parenting stress across the 14 days was previously found (Hartley et al., 2016) to be significantly positively correlated (ASD group: r = .65,p < .01 and comparison group: r = 67,p < .01) with the total score from the Zarit Burden Interview (Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985), a global measure of parenting stress. This single-item measure of daily level of parenting stress was previously found (Hartley et al., 2016) to be significantly positively correlated with parent’s report of the severity of same-day child behavior problems.

Positive and negative couple interactions.

On each day of the 14-day daily diary, parents reported on their subjective perception of having engaged in (0 = No, 1 = Yes) eight types of positive couple interactions and eight types of negative couple interactions in the past 24 hours. These interactions could occur in person or via text/email/phone. Perceived positive couple interactions included: gave a compliment, kissed or hugged, had sex, did a fun activity, shared a joke or funny story, communicated a positive feeling toward, had a meaningful conversation, and ‘other’. Perceived negative couple interactions included: interrupted when talking, made a critical comment about, avoided talking to or being around, did not do something he/she wanted you to do, expressed frustration or anger toward, was impatient or short-tempered with, did not fully listen to, and ‘other’. Total number of types of perceived positive and negative couple interactions a day was used in analyses.

This measure of perceived daily positive and negative couple relationship interactions has been used in previous daily diary investigations with parents of children with ASD (i.e., Hartley, Papp, Blumenstock, Floyd, & Goetz, 2016) and in other populations (Quittner et al., 1998). The measure was found to have adequate internal consistency (Cronbach α ranging .71 to .77) in parents of children with chronic illnesses (Quittner et al., 1998), and in a previous study reporting on the current sample for perceived positive couple interactions (ASD group: Cronbach α = 0.70; comparison group: Cronbach α = 0.71) and negative couple interactions (ASD group: Cronbach α = .68; comparison group: Cronbach α = 0.67) (Hartley et al., 2016). In the current sample, the average daily (i.e., mean across the 14-day daily diary) perceived positive couple interactions was significantly positively correlated with a global measure of couple relationship satisfaction – the Couple Satisfaction Index (CSI; Funk & Rogge, 2007) – in mothers (r = .47, p < .01) and fathers (r = .39,p < .01). The average daily perceived negative couple interactions was negatively correlated with the CSI at a significant level in mothers (r = −.28,p < .01), and at a trend-level in fathers (r = −.21, p = .09). The CSI is a 32-item measure that has been previously used in parents of children with ASD (e.g., Ekas, Timmons, Pruitt, Ghilain, & Alessandri, 2015) and shown to have good reliability and validity (Funk & Rogge, 2007).

Data Analysis Plan

Only daily diary entries made on the same date by both partners in the couple, and only entries spaced 18–26 hours apart, were included in analyses. This resulted in the inclusion of 93.2% of all diary entries. Of these diary entries, 4.3% of entries had one or more missing item of interest; however, these diary entries were included in multilevel models (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013) as Hierarchical Linear Model (HLM v. 7; Raudenbush et al., 2011) is able to handle missing Level 1 data. Participants with missing data items did not differ significantly in socio-demographics variables (parent age, household income, parent education, couple relationship length, child age, and child severity of ASD symptoms) from those without missing data items. Prior to conducting the multilevel models, histograms were used to check the normalcy of variables. Descriptive statistics and one-way multivariate analysis of co-variance (MANCOVA), controlling for family demographics that differed by group, were used to examine differences in study variables between the ASD and comparison groups.

The research questions were examined using two dyadic multilevel models (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013) in HLM software. The dependent variables were number of types of perceived positive couple interactions and perceived negative couple interactions. These models assessed actor and partner associations separately for mothers and fathers in one model. The models also controlled for the nested structure of couple data, and examined within-person daily associations while controlling for between-person differences in socio-demographics and mean daily level of parenting stress, in line with Hoffman (2015) recommendations. In both multilevel models, the Level 1 intercept was removed to create separate mother and father intercepts at Level 2. In order to interpret differences in effects for mothers versus fathers, mothers were coded 0 for all husband variables and vice versa. Level 1 variables included: mother (dummy coded: 1 = mothers, 0 = fathers) and father (dummy coded: 1 = fathers, 0 = mothers), day of the daily diary (i.e., 0–13), actor daily level of parenting stress, and partner daily level of parenting stress. A partner moderation variable was included in Level 1, computed as the interaction of actor daily level of parenting stress x partner daily level of parenting stress. Level 1 dummy variables were un-centered and continuous variables were group-centered (i.e., centered around each individual’s distribution for that variable). Level 2 variables included: group (contrast coded: 1 = ASD, −1 = comparison), child age, household income, and couple relationship length. In addition, mean daily level of parenting stress was included at Level 2 in order to control for between-person differences in global (or average) level of parenting stress. Level 2 contrast variables were un-centered and continuous variables were grand-mean centered. The HLM equation predicting perceived positive couple interactions is below.

Level 1: Positive Couple Interactions = β1 (mother dummy) + β2 (father dummy) + β3 (mother day; Day 1 = 0) + β4 (father day; Day 1 = 0) + β5 (mother actor daily level of parenting stress) + β6 (father actor daily level of parenting stress) + β7 (mother partner daily level of parenting stress + β8 (father partner daily level of parenting stress,) + β9 (mother actor daily parenting stress level x partner daily parenting stress level) + β10 (father actor daily parenting stress level x partner daily parenting stress level) + R

Level 2: β1 = γ10 + γ11 (group; dichotomously coded) + γ12 (household income) + γ13 (education level) + γ14 (relationship length) + γ15 (child age) + γ16 (mean mother daily level of parenting) + u1

β2 = γ20 + γ21 (group; dichotomously coded) + γ22 (household income) + γ23 (education level) + γ24 (relationship length) + γ25 (child age) + γ26 (mean mother daily level of parenting) + u2

β3 = γ30 + u3

β4 = γ40 + u4

β5 = γ50 + γ51 (group; dichotomously coded) + u5 β6 = γ60 + γ61 (group; dichotomously coded) + u6

β7 = γ70 + γ71 (group; dichotomously coded) + u7

β8 = γ80 + γ81 (group; dichotomously coded) + u8

β9 = γ90 + γ91 (group; dichotomously coded) + u9

β10 = γ10 + γ101 (group; dichotomously coded) + u10

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The ASD (M = 13.72, SD = 2.27) and comparison (M = 13.66, SD = 2.31) groups completed a similar number of daily diary entries. Descriptive statistics indicated a normal distribution of variables, with the exception of number of types of perceived negative couple interactions (skewness of 1.77 [SE = 0.05]; kurtosis of 3.08 [SE = 0.07]). A square-root transformation was created with a Poisson distribution. The pattern of results did not change when using the transformed versus untransformed score; thus, results are only reported for the untransformed score to aid in interpretability of effects. Table 1 displays the mean and standard deviation for the mean daily level of parenting stress, perceived positive couple interactions and perceived negative couple interactions. The omnibus MANCOVA, with covariates of maternal education and household income, examining differences in mothers and fathers by group was significant ( Λ = 0.69, F (1, 358) = 20.94, p < .001). Mothers and fathers in the ASD group evidenced a higher mean daily level of parenting stress than parents in the comparison group (mothers: F (1, 358) = 92.69, p < .001; fathers: F (1, 358) = 50.52, p < .001). Mothers and fathers in the ASD group also evidenced a lower mean daily number of types of perceived positive couple interactions than parents in the comparison group (mothers: F (1, 358) = 13.94,p < .001; fathers: F (1, 358) = 11.77, p = .001), but a similar mean daily number of types of perceived negative couple interactions (mothers: F (1, 358) = 0.44, p = .51; fathers: F (1, 358) = 0.08 p = .67), which we have previously reported (Hartley, DaWalt, & Schultz, 2017). Paired sample t-tests indicated that within-couples, mother and father mean daily level of parenting stress were significantly positively associated in both the ASD (r = .36,p < .001) and comparison (r = .34, p < .001) groups. Similarly, within-couples, mother and father mean daily number of types of perceived positive (ASD: r = .52,p < .001; comparison: r = .53,p < .001) and negative (ASD: r = .31 , p < .001; comparison: r =.40, p <.001) couple interactions were significantly positively associated in the ASD and comparison groups.

Actor and Partner Daily Level of Parenting Stress and Perceived Couple Interactions

Positive Couple Interactions.

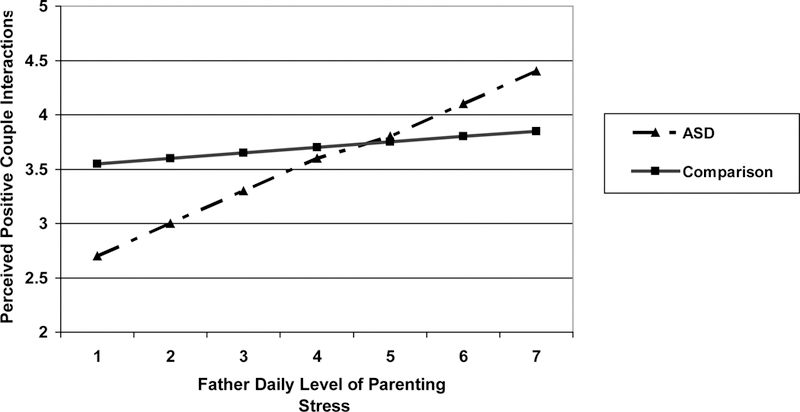

Table 2 displays the results of the multilevel model examining actor and partner daily level of parenting stress and number of types of perceived positive couple interactions in the ASD and comparison groups. At a between-person level, there was a significant group effect for the intercept (i.e., Day 1) of daily number of types of perceived positive couple interactions for fathers and a trend-level effect for mothers; in both cases, the comparison group reported a higher intercept (i.e., Day 1) number of types of perceived positive couple interactions than the ASD group. Fathers who had a lower household income and who had been in their couple relationship for a shorter length of time reported a higher initial (i.e., Day 1) number of types of perceived positive couple interactions. After controlling for between-person effects, at a within-person level, mother’s daily level of parenting stress significantly negatively co-varied with her own daily number of types of perceived positive couple interactions. In direct contrast, fathers’ daily level of parenting stress significantly positively co-varied with his daily number of types of perceived positive couple interactions. A chi-square statistic indicated that there was a significant difference in this association between mothers and fathers (χ2 (1) = 4.92, p = .03). There was a significant effect of group status (i.e., ASD vs. comparison) on the association between actor daily level of parenting stress and number of types of perceived positive couple interactions for fathers. As shown in Figure 1, the positive association between father’s daily level of parenting stress and his perceived positive couple interactions only occurred in the ASD group. Father’s daily level of parenting stress was not associated with his perceived positive couple interactions in the comparison group. Indeed, a test for difference in simple slopes (bdifference = .27−.05 = 0.22, SE pooled = .07, t (357) = .22 / .07 = 3.14, p = .02) indicated a significant difference in the slope for the association between father’s daily level of parenting stress and his perceived positive couple interactions between the ASD and comparison groups.

Table 2.

Actor and Partner Daily Level of Parenting Stress and Number of Types of Perceived Positive and Negative Couple Interactions in Mothers and Fathers in the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Comparison groups.

| Positive Couple Interactions | Negative Couple Interactions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Father | Mother | Father | |||||

| Unstandardized coefficients (standard error) |

F value | Unstandardize d coefficients (standard error) |

F value | Unstandardized coefficients (standard error) |

F value | Unstandardized coefficients (standard error) |

F value | |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Day | 0.02 (0.01) | 2.89* | 0.01 (.001) | 1.16 | −0.02 (0.01) | 2.84* | −0.02 (0.01) | 2.56* |

| Actor Daily Parenting Stress | −0.12 (0.06) | −2.06* | 0.14 (0.07) | 2.04* | 0.05 (0.04) | 1.22 | 0.07 (0.05) | 1.27 |

| X Group | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.36 | 0.07 (0.04) | 1.99* | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.61 | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.51 |

| Partner Daily Parenting Stress | −0.02 (0.06) | 0.26 | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.89 | −0.009 (0.05) | −0.20 | −0.05 (0.04) | −1.09 |

| X Group | −0.05(0.06) | 0.79 | 0.03 (0.06) | 0.60 | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.32 | 0.004 (0.04) | 0.09 |

| Actor X Partner Daily Parenting Stress | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.95 | −0.04 (0.03) | 1.54 | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.96* | 0.04 (0.02) | 2.05* |

| X Group | −0.001 (0.02) | −0.09 | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.58 | −0.01 (0.004) | −2.08* | 0.004 (0.02) | 0.22 |

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Intercept | 3.33 (0.14) | 24.28** | 3.30 (0.15) | 22.44** | 0.87 (0.08) | 10.89** | 0.71 (0.08) | 8.43** |

| Group | −0.16 (0.11) | 1.87+ | −0.48 (0.15) | −3.25** | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.37 | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.54 |

| Child Age | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.50 | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.21 | 0.004 (0.02) | 0.21 | −0.001 (0.02) | −0.4 |

| Parent Education | −0.10 (0.06) | −1.68 | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.99 | 0.03 (0.03) | 1.01 | 0.005 (0.03) | 0.18 |

| Household Income | 0.002 (0.02) | 0.06 | −0.06 (0.03) | −1.98* | −0.03 (0.02) | −1.64 | −0.04 (0.02) | −2.28* |

| Relationship Length | −0.02 (0.02) | −1.34 | −0.04 (0.02) | −2.03* | −0.02 (0.009) | −2.27* | −0.01 (0.009) | −1.55 |

| Mean Parent Daily Parenting Stress | −0.13 (0.13) | −0.98 | 0.04 (0.13) | 0.73 | 0.19 (0.08) | 2.40* | 0.14 (0.07) | 2.03* |

Note.

p < .08,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Group: ASD = 1, comparison = −1. Daily time spent with partner (as reported by each parent) was significantly correlated with number of types of perceived positive couple interactions (r = .22, p = .02) but not perceived negative couple interactions (r = .14, r = .21). As a follow-up, we r-ran the above models to include daily time spent with partner in Level 1. The pattern of significant associations remained the same when this variable was included.

Figure 1.

Father Daily Level of Parenting Stress and Perceived Positive Couple Interactions in the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) versus comparison group.

There was not a significant association between partner daily level of parenting stress and actor same-day perceived positive couple interactions in mothers or in fathers. The moderation variable - actor x partner daily level of parenting stress – was also not significantly associated with perceived positive couple interactions in mothers or in fathers.

Negative Couple Interactions.

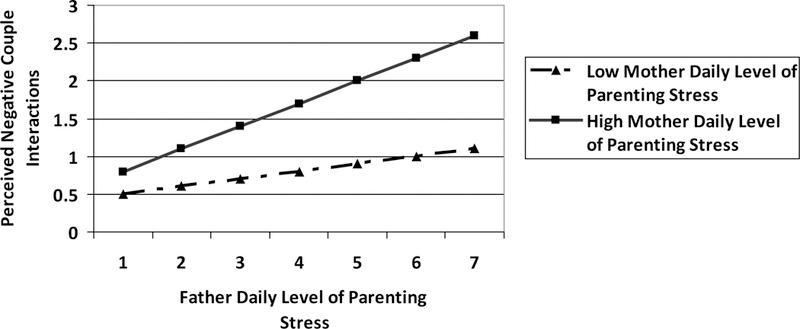

Table 2 also displays the results of the multilevel model examining actor and partner daily level of parenting stress and number of types of perceived negative couple interactions in the ASD and comparison groups. At a between-person level, household income and mean daily level of parenting stress were significantly related to fathers’ intercept (i.e., Day 1) for perceived negative couple interactions, in negative and positive directions, respectively. Relationship length and mean daily level of parenting stress were significantly related to between-person difference in mothers’ intercept for perceived negative couple interactions, in negative and positive directions, respectively. After controlling for between-person effects, there were no significant within-person associations between actor or partner daily level of parenting stress and perceived negative couple interactions in mothers or in fathers. The moderation variable – actor daily level of parenting stress x partner daily level of parenting stress - was significantly associated with perceived negative couple interactions in both fathers and mothers. Chi-square statistics indicated that there was not a significant difference in the strength of this association between mothers and fathers (χ2 (1) = 1.29, p = .59). A test for difference in simple slopes (bdifference = .03 −.01 = 0.02, SE pooled = .006, t (355) = .02 / .006 = 3.33, p = .02) indicated a significant difference in the slopes for the association between father daily level of parenting stress and perceived negative couple interactions on days when mothers reported high (1 SD above the mean) versus low (1 SD below the mean) parenting stress. As shown in Figure 2, father daily level of parenting stress was only positively related to his perceived negative couple interactions on days when his partner reported high (1 SD above the mean) rather than low (1 SD below the mean) daily level of parenting stress.

Figure 2.

Moderating Effect of Mother Daily Level of Parenting Stress on the relation between Father’s Daily Level of Parenting Stress and Perceived Negative Couple Interactions

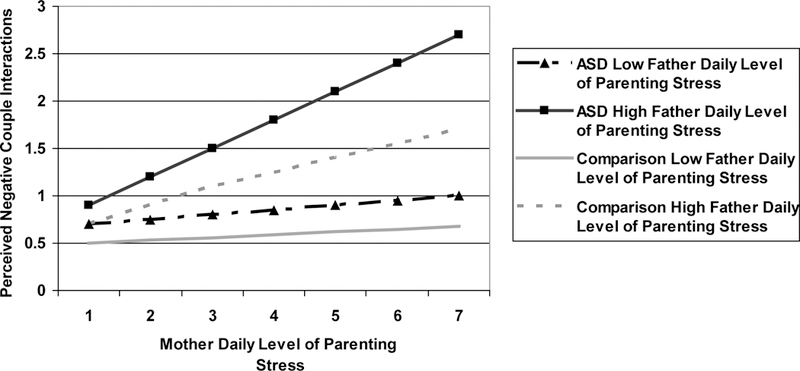

Group status significantly altered this moderation effect in mothers, with the interaction more evident in the ASD than comparison group. As shown in Figure 3, in both the ASD and comparison groups, mother daily level of parenting stress was only positively related to her perceived negative couple interactions on days when her partner reported high (1 SD above the mean) rather than low (1 SD below the mean) daily level of parenting stress. However, the difference in simple slopes for the association between mother daily level of parenting stress and her perceived negative couple interactions on days when fathers reported high (1 SD above mean) versus low (1 SD below mean) daily level of stress was significant for ASD mothers (bdifference = 0.30 −0.05 = 0.25, SE pooled = .06, t = 0.25 / 0.06 = 4.17, p = .01), but at trend-level for comparison mothers (bdifference = 0.16 −0.03 = 0.13, SE pooled = .05, t = 0.13 / 0.05 = 2.60, p = .07).

Figure 3.

Moderating Effect of Father Daily Level of Parenting Stress on the relation between Mother’s Daily Level of Parenting Stress and Perceived Negative Couple Interactions in the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and comparison groups.

Discussion

Parents of children with ASD are at increased risk for both a high level of parenting stress (e.g., Estes et al., 2013) and poor couple relationship outcomes (e.g. Gau et al., 2012; Hartley et al., 2010; Hartley et al., 2017). Using a family system perspective (Fine & Finchman, 2013), and drawing on the concept of stress spillover (Almeida et al., 1999) and crossover (e.g., Falconier et al., 2015), the goal of the current study was to examine same-day associations between daily level parenting stress and perceived couple interaction experiences of mothers and fathers in couples who had a child with ASD. The study built on previous research by examining both actor and partner associations, as well as their interaction, and separately in mothers versus fathers. Moreover, we included a comparison group of parents of children without neurodevelopmental disabilities to inform whether daily spillover between the parenting and couple domains is stronger in a context of high parenting stress associated with child ASD.

We found important associations between one’s own daily level of parenting stress and her/his perceived couple interactions in models controlling for average-level partner daily stress. These actor associations differed for mothers versus fathers. For mothers in both the ASD and comparison groups, one’s own daily level of parenting stress negatively co-varied with her number of types of perceived positive couple interactions. This finding is consistent with previous studies that parenting stress is related to lower couple relationship quality in both the general population (e.g., Falconier et al., 2015) and parents of children with ASD (Langley et al., 2017). On days marked by high parenting stress, mothers may not have the energy or desire to initiate positive couple interactions and may engage in attributional processes that overlook or discredit the efforts of their partners in this regard. In contrast to this pattern, fathers’ own daily level of parenting stress positively co-varied with his perceived positive couple interaction experiences in the ASD group. Thus, on days when fathers of children with ASD experienced a high level of parenting stress, they were also more likely to perceive having a relatively greater variety of positive couple interactions. One interpretation of this mother-father difference is that daily stress spillover occurs between the parenting and couple domains in expected ways in mothers regardless of child ASD status. On the other hand, when fathers of children with ASD are faced with a day with high parenting stress, they may initiate more positive couple interactions, perhaps as a means of coping with this stress (e.g., seek out meaningful conversations and physical contact with partner). In research on the general population, women have been found to provide more support to stressed partners than men (Falconier et al., 2015; Neff & Karney, 2005). Thus, it is also possible that mothers of children with ASD offered more positive couple interactions when fathers were stressed as a means of helping fathers cope. This pattern was not seen in fathers in the comparison group. Thus, the increase in perceived positive couple interactions in the face of a stressful day in fathers may be most prominent when undergoing chronic parenting stress, such as that seen with child ASD (e.g., Estes et al., 2013).

In contrast to our hypothesis, partner daily level of parenting stress was not directly associated with one’s own perceived positive or negative couple interactions in mothers or fathers, in either the ASD or comparison group. Instead, in accordance with our hypothesis, there was a significant interaction between actor daily level of parenting stress and partner daily level of parenting stress on perceived negative couple interactions in both mothers and fathers. In contrast to our hypothesis, the moderating effect of partner daily level of parenting stress on the association between actor daily level of parenting stress and actor perceived negative couple interactions was of similar strength across genders. For both mothers and fathers, one’s own daily level of parenting stress was only positively related to perceiving that they had a greater variety of negative couple interactions when her/his partner also reported a high daily level of parenting stress. This finding is consistent with previous studies on the general population which also found that the association between stress and the couple relationship is heightened if both partners in the couple are undergoing a higher than typical level of stress (e.g., Falconier et al., 2015; Neff & Karney, 2005). In previous studies, individuals within a couple were more likely to reciprocate the negative behaviors of her/his partner when they were stressed (e.g., Sears et al., 2016). Thus, if both parents of children with ASD are having a high parenting stress day, an escalating pattern of negative couple behaviors may occur that day. In addition to actually having more types of negative couple interactions, experiencing a stressful parenting day may also make parents of children with ASD prone to attributional processes in which they blame partners for couple problems, further contributing to the subjective experience of negative couple interactions, as seen in the general population (Neff & Karney, 2004).

In mothers, the interaction of actor daily level of parenting stress X partner daily level of parenting stress on perceived negative couple interactions was stronger in the ASD group than the comparison group. Thus, in support of our hypothesis, partners appear to play a particularly strong role in shaping the impact of a high parenting stress day in a context of child ASD. This vulnerability to partner level of daily stress (i.e. acute stress) may stem from the chronically high level of parenting stress reported by parents of children with ASD (e.g. Estes et al., 2013). Indeed, in previous studies, in contexts of other types of chronic stressors individuals were more strongly influenced by the negative emotions of her/his partners within interdependent relationships (e.g., Larson & Almeida, 1999; Neff & Karney, 2007).

There are several strengths to the current study. We examined associations between actor and partner daily level of parenting stress and perceived positive and negative couple interactions separately in mothers and fathers. Yet, we controlled for the linked nature of couple data through our multilevel models. Our daily diary methodology minimizes error in retrospective reporting associated with global ratings covering long periods of time and allowed us to capture associations as they naturally unfold in an everyday context. Both perceived positive and perceived negative couple interactions were assessed given evidence that these dimensions uniquely contribute to couple relationship quality (e.g., Boerner et al., 2014), and both are influenced by partner level of stress (e.g., Neff & Karney, 2004).

The current study is not without limitations. The sample was predominately white, non- Hispanic and of middle socioeconomic status, which reduces the generalizability of findings. We focused on same-day associations between daily level of parenting stress and perceived couple interactions. The current study stems from theory and evidence that actor and partner stress shape perceived couple experiences and are shaped by these experiences(Hartley et al., 2016). In our future work, we will need to examine time-ordered associations using lagged models to see if these associations occur from one-day-to-the-next. The current study captured mothers’ and fathers’ subjective perceptions of number of types of positive and negative couple interactions. This was done given that parents are likely to differ in their perceptions of couple interactions on a given day. Moreover, while some items asked about interactions that involve actions by both partners (e.g., kiss/hug partner that day), other items asked about interactions that may only have been done by one partner (e.g., ignored partner that day). In the current study, we cannot disentangle actual couple interactions from attributional processes which may influence the extent to which parents are aware of and/or give credit/blame to their partner for couple behaviors. Indeed, as has been seen in the general population (Neff & Karney, 2004), stress is likely to shape both actual couple interactions and attributions of these interactions. The current study is also limited in that it assessed the number of different types of positive and negative couple interactions and did not capture how many interactions of any one type were experienced. The role of diversity or variation in couple interactions relative to total number is not clear in the literature and should be examined in future research. Future research should also take into account objective measures of couple relationship functioning.

Future studies need to identify personality traits and mental health conditions that may shape the impact of actor and partner daily level of stress on actual couple interactions and/or alter attributions for partner behaviors. Future studies should also consider other life stressors (e.g., work stress) or the pile up of multiple stressors in a context of child ASD.

Implications

Findings highlight the importance of understanding parent experiences as a function of the family system, including stress spillover across the parenting and couple subsystems, as well as cross-partner effects. For mothers (in both groups), a stressful parenting day was associated with subjectively experiencing fewer positive couple interactions. In contrast, when fathers of children with ASD had a stressful parenting day, they experienced more positive couple interactions. Thus, in line with gender findings from the general population (e.g., Neff & Karney, 2005), experiencing a stressful parenting day has different associations for one’s own perceived couple interactions in mothers versus fathers of children with ASD. We also found that, within couples, whether a stressful parenting day is associated with greater perceived negative couple interactions was influenced by one’s partner. Having a partner who is also experiencing a stressful parenting day appeared to exacerbate the spillover of stress. High parenting stress in both parents in the couple could foster an escalating pattern of perceived negative couple interactions, such that both partners initiate negative couple interactions (e.g., critical comments or ignoring), and/or respond in negative ways to their partner’s negative behaviors, and both may blame partners for couple problems. This was true for both mothers and fathers and in ASD and comparison groups. However, the association was stronger in mothers of children with ASD than mothers in the comparison group, suggesting that a context of chronic high parenting stress may mean that parents are more sensitive to her/his partner’s daily level of stress. Psychoeducational programs that increase awareness about stress spillover between the parenting and couple domains may help foster positive family experiences in families of children with ASD. For example, strategies could be aimed at breaking the cycle of escalating negative couple relationship behaviors when both parents are experiencing a day with high parenting stress.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH009190 to S. Hartley) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54 HD090256 to Q. Chang).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors Goetz, Rodriguez, and Hartley declare no conflict of interest.

Parts of this study were presented at the 51st Annual Gatlinburg Conference on Research and Theory in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Contributor Information

Greta L. Goetz, Department of Human Development and Family Studies and Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Geovanna Rodriguez, Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison..

Sigan L. Hartley, Department of Human Development and Family Studies and Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, & Chandler AL (1999). Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent-child dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 49–61. doi: 10.2307/353882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of developmental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Berg KL, Cheng-Shi S, Acharya K, Stolbach BC, & Msall ME (2016). Disparities in adversity among children with autism spectrum disorder: A population-based study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 58, 1124–1131. doi: 10.1111/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Jopp DS, Carr D, Sosinsky L, & Kim SK (2014). “His” and “her” marriage? The role of positive and negative marital characteristics in global marital satisfaction among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 579–589. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, & Laurenceau J (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network. Retrieved August 1, 2018, from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html.

- Choi KK, & Kovshoff H (2013). Do maternal attributions play a role in the acceptability of behavioural interventions for problem behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders?. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 984–996. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, & Gruber CP (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, & Harter K (2001). Interparental conflict and parent-child relationships. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications, 249–272. doi: 10.1017/CB09780511527838.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1988). The impact of daily stress on health and mood: psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of personality and social psychology, 54(3), 486. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Timmons L, Pruitt M, Ghilain C, & Alessandri M (2015). The power of positivity: Predictors of relationship satisfaction for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1997–2007. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Olson E, Sullivan K, Greenson J, Winter J, Dawson G, & Munson J (2013). Parenting-related stress and psychological distress in mothers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain & Development, 35, 133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconier MK, Nussbeck F, Bodenmann G, Schneider H, & Bradbury T (2015). Stress From Daily Hassles in Couples: Its Effects on Intradyadic Stress, Relationship Satisfaction, and Physical and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 41, 221–235. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M, & Finchman F (2013). Handbook of Family Theories: A Content-Based Approach. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, & Rogge RD (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 572. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Chou M, Chiang H, Lee J, Wong C, Chou W, & Wu Y (2012). Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, & Lord C (2006). The autism diagnostic observation schedule: Revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 613–627. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Baker JK, Seltzer MM, & Greenberg JS (2012). Marital satisfaction and life circumstances of grown children with autism across 7 years. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 688–693. doi: 10.1037/a0029354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Greenberg J, Orsmond G, & Bolt D (2010). The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 449–457. doi: 10.1037/a0019847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, DaWalt LS, & Schultz HM (2017). Daily Couple Experiences and Parent Affect in Families of Children with Versus Without Autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(6), 1645–1658. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3088-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Papp LM, Blumenstock SM, Floyd F, & Goetz GL (2016). The effect of daily challenges in children with autism on parents’ couple problem-solving interactions. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(6), 732. doi: 10.1037/fam0000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Papp LM, & Bolt D (2016). Spillover of Marital Interactions and Parenting Stress in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1152552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Papp LM, Mihaila I, Bussanich PM, Goetz G, & Hickey EJ (2017). Couple Conflict in Parents of Children with versus without Autism: Self-Reported and Observed Findings. Journal of child and family studies, 26(8), 2152–2165. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0737-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L (2015). Longitudinal analysis: Modeling within-person fluctuation and change. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GL, Trail TE, Kennedy DP, Williamson HC, Bradbury TN, & Karney BR (2016). The salience and severity of relationship problems among low-income couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 2–11. doi: 10.1037/13619-016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Story LB, & Bradbury TN (2005). Marriages in context: Interactions between chronic and acute stress among newlyweds. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Langley E, Totsika V, & Hastings RP (2017). Parental relationship satisfaction in families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A multilevel analysis. Autism Research, 10(7), 1259–1268. doi: 10.1002/aur.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, & Almeida DM (1999). Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 5–20. doi: 10.2307/353879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, Leone S, & Wiltz J (2006). The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50, 172–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter V, Krauss MW, Anderson B, & Wells N (2004). The consequences of caring: Effects of mothering a child with special needs. Journal of Family Issues, 25(3), 379–403. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03257415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lickenbrock DM, Ekas NV, & Whitman TL (2011). Feeling good, feeling bad: Influences of maternal perceptions of the child and marital adjustment on well-being in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 848–858. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, & Karney BR (2004). How does context affect intimate relationships? linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(2), 134–148. doi: 10.1177/0146167203255984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, & Karney BR (2005). Gender differences in social support: A question of skill or responsiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 79–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, & Karney BR (2007). Stress crossover in newlywed marriage: A longitudinal and dyadic perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 594–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quittner AL, Espelage DL, Opipari LC, Carter B, Eid N, & Eigen H (1998). Role strain in couples with and without a child with a chronic illness: associations with marital satisfaction, intimacy, and daily mood. Health Psychology, 17, 112–117. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, & Bodenmann G (2017). Stress and its associations with relationship satisfaction. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong AS, Fai YF, Congdon RT, & du Toit M (2011). HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn AC, Cummings EM, DeCarlo CA, & Davies PT (2007). Children’s influence in the marital relationship. Journal of Family psychology, 21, 259. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears MS, Repetti RL, Reynolds BM, Robles TF, & Krull JL (2016). Spillover in the home: Effects of family conflict on parents’ behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 127–141. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sochos A, & Yahya F (2015). Attachment style and relationship difficulties in parents of children with ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3711–3722. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0179-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, & Bolger N (1999). Emotional transmission in couples under stress. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 38–48. doi: 10.2307/353881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wymbs BT, Pelham WE Jr., Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Wilson TK, & Greenhouse JB (2008). Rate and predictors of divorce among parents of youths with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 735–744. doi: 10.1037/a0012719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Orr NK, & Zarit JM (1985). The hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: Families under stress. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]