Abstract

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder report elevated parenting stress. The current study examined bidirectional effects between parenting stress and three domains of child functioning (ASD symptoms, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems) across four time points in 188 families of children with ASD (ages 5–12 years). Mother and father reports of parenting stress and child functioning were used in cross-lag models to examine bidirectional associations between parenting stress and child functioning. Results indicated parent-driven effects for child internalizing behavior problems, while child externalizing behavior problems and ASD symptoms evidenced both parent-driven and child-driven effects, in different ways for mothers versus fathers. Overall, findings have important implications for interventions for families of children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism, Parent stress, Behavior problems, Father, Mother

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) report a higher level of parenting stress than parents of children without developmental disabilities (DD) and parents of children with other types of DD (Estes et al. 2009; Hastings 2003; Hayes and Watson 2013). In addition to ASD symptoms, which include impairments in social interaction and communication, along with restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2013), children with ASD exhibit high rates of co-occurring internalizing (e.g., anxiety and depressed mood) and externalizing (e.g., hyperactivity and aggression) behavior problems (Kaat and Lecavalier 2013; White et al. 2009). Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated associations between the child with ASD’s severity of ASD symptoms and behavior problems and mother and father parenting stress (e.g., Benson 2006; Davis and Carter 2008; Lecavalier et al. 2006; Hartley et al. 2011). In these studies, and ASD literature more broadly, it is generally assumed that the child’s severity of ASD symptoms and behavior problems drive increases in parenting stress. Yet, transactional models of child development (Hastings 2002; Sameroff 2009) suggest that child and parent interactions are linked in ongoing reciprocal ways. Within a transactional model, the child with ASD’s symptoms and behavior problems contribute to increased parenting stress, which inadvertently alters parenting behaviors in ways that reinforce the child’s ASD symptoms and behavior problems (Guralnick 2011). The current study adds to the small body of longitudinal research examining bidirectional effects between parenting stress and child functioning in families of children with ASD. We build on previous studies by examining how associations differ by domain of child functioning (i.e., ASD symptoms vs. internalizing behavior problems vs. externalizing behavior problems) and for mothers versus fathers of children with ASD.

To date, only a handful of longitudinal studies have tested bidirectional relations between parenting stress and the functioning of children with ASD or other DD (Neece et al. 2012; Woodman et al. 2015; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2014). The majority of these studies focused on children with developmental delays broadly. Overall, bidirectional associations between parenting stress and child behavior problems were reported, but the direction of effects differed by child developmental stage and domain of child functioning. In a 15-year longitudinal study of families of children with developmental delays (Woodman et al. 2015), child internalizing behavior problems and parenting stress were bidirectionally related in early childhood (ages 3–5 years), whereas child externalizing behavior problems and parenting stress were not associated (in either direction). Neece and colleagues (2012) similarly found that bidirectional effects between overall child behavior problems (summed rating of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems) and parenting stress were strongest in early childhood (aged 3–9 years) in their sample of families of children with developmental delays. In contrast to early childhood, Woodman et al. (2015) only observed child-driven effects (i.e., child behavior problems predicted later parenting stress but not vice versa) for both internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in mid to late childhood (ages 5–10 years). In late childhood to early adolescence (ages 10–15 years), child-driven effects were observed for externalizing behavior problems, but there was not an association between child internalizing behavior problems and parenting stress. Finally, only parent-driven effects (i.e., parenting stress predicted later child behavior problems but not vice versa) occurred for both child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in mid to late adolescence (Woodman et al. 2015). In summary, in families of children with developmental delay, there is evidence for reciprocal influences between parents and children in early childhood, child-driven effects in mid childhood to early adolescence, and parent-driven effects in mid to late adolescence. Moreover, child internalizing behavior problems appear to have stronger effects on parenting stress early in childhood, whereas child externalizing behavior problems have stronger effects on parenting stress in late childhood and early adolescence.

Only one published longitudinal study (Zaidman-Zait et al. 2014) has examined bidirectional links between parenting stress and child functioning in families of children with ASD. This study examined early childhood (ages 3–6 years). In contrast to the pattern seen for families of children with developmental delay, Zaidman-Zait et al. (2014) found only parent-driven effects for both child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (i.e., parenting stress predicted later increases in child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems but not vice versa). It is possible that the heightened level of parenting stress reported by parents of children with ASD, relative to parents with other types of DD (e.g., Estes et al. 2013; Hayes and Watson 2013), means that parenting stress is a particularly strong determinant of child functioning in families of children with ASD. Given globally high parenting stress, parents of children with ASD may be more reactive to their child’s behavioral challenges. Alternatively, it is possible that children with ASD are more sensitive to negative parenting responses that stem from parenting stress than are children with other types of DD; as a result, children with ASD may show greater change in behavior problems following high parenting stress responses.

Further research in ASD samples is needed to explore whether the direction of associations between child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and parent stress is similar at later child developmental stages. Research is also needed to examine whether the severity of child ASD symptoms are linked in bidirectional ways with parenting stress. To-date, longitudinal studies examining bidirectional effects between child functioning and parenting stress have been limited to internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Previous longitudinal investigations of the association between child ASD symptom severity and parenting stress have reported an effect of severity of child ASD symptoms on later parenting stress (Estes et al. 2013). However, the opposite direction of effects (i.e., effect of parenting stress on later child ASD symptom severity) was not examined, and thus it is not clear if parenting stress also drives increases in child ASD symptom severity. Finally, there is a need to examine whether transactional links between parenting stress and child functioning differ for mothers versus fathers of children with ASD. In previous studies, mothers of children with ASD reported higher parenting stress than fathers (Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Lounds et al. 2007). Given our hypothesis that a context of globally high parenting stress may mean that parenting stress is a strong determinant of child functioning, it possible that mothers will evidence more parent-driven pathways than fathers of children with ASD.

Current Study

The goal of the current study was to examine the bidirectional associations between parenting stress and the severity of child ASD symptoms and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems across four time points, spanning 3 years in mid to late childhood (children with ASD originally aged 5–12 years). There was one overall research question with two sub-questions: What is the direction of effects between parenting stress and the functioning of children with ASD? (a) Do these effects differ based on the domain of child functioning—ASD symptoms, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems? (b) Do these effects differ for mothers versus fathers? Based on prior research (Zaidman-Zait et al. 2014), we expected to find stronger parent-driven effects (i.e., parenting stress would positively predict later child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems) than child-driven effects. In contrast, severity of child ASD symptoms was hypothesized to be a stronger predictor of later parenting stress than vice versa given prior evidence (Estes et al. 2013). Given previous reports that mothers’ have higher parenting stress than fathers of children with ASD (e.g., Dabrowska and Pisula 2010), parent-driven effects (i.e., parenting stress positively predicting later change in child functioning) were hypothesized to be stronger in mothers than in fathers.

Method

Participants in this study were part of an ongoing longitudinal study in Midwestern, United States. The original sample consisted of 188 families whose child had received a diagnosis of ASD and was aged 5–12 years. Participants were recruited through school mailings, postings on websites, listservs, and agencies that service families of children with ASD. Parents provided medical or educational records to document that the child had received a diagnosis of ASD and this diagnostic evaluation had to have included the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al. 1989, ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012). All but five children had a Total t score ≤ 60 on the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino and Gruber 2012) based on parent report. However, based on review of all information (i.e., medical/educational records, ADOS scores, and teacher report of SRS-2) it was ultimately determined that these children met diagnostic criteria for ASD and were included in the sample. Study inclusion criteria also included parents being in a long-term committed relationship (≥ 3 years) in which they cohabited, and both parents agreeing to be in the study.

The current study is based on four waves of data collection that occurred over the course of 3 years, referred to as Time 1 (T1), Time 2 (T2), Time 3 (T3), and Time 4 (T4), which were spaced approximately 12 months apart. Table 1 provides a summary of parent and child socio-demographic information for the 188 families at T1. Parents had an average age of 39.68 years (SD = 5.98); mothers (M = 38.7, SD = 5.6) and fathers (M = 40.7, SD = 6.2). The target child with ASD had an average age of 7.90 years (SD = 2.3). The majority of target children were male (86%), less than half had intellectual disability (34.6%), and 10.7% were of ethnic/racial minority status. Across the four time points, 22% of the families dropped out of the study (T2 = 171, T3 = 151, T4 = 146). The reasons for dropping out of the study included: moved (n = 6), could not be reached (n = 12), declined (n = 15), and divorced/separated (n = 8). Families who dropped out of the study did not significantly differ from those who remained in the study in maternal age (t (187) = 1.12 p = .27), child age (t (187) = 1.16, p = .0.35), maternal years of education (t (187) = 0.28 p = .0.78), paternal years of education (t (187) = 0.31 p = .0.76), household income (t (187) = - 0.38, p = .0.71), child SRS-2 Total score (t (187) = 1.08, p = .0.29) or CBCL Total score (t (187) = - 0.53, p = .0.58).

Table 1.

Family socio-demographic information at Time 1

| Families of children with ASD (N = 188) | |

|---|---|

| Parents | |

| Mother’s age, years (M [SD]) | 38.7 (5.6) |

| Father’s age, years (M [SD]) | 40.7 (6.2) |

| Income (M [SD]) | US$80– 89,000 (US$30,000) |

| Education (n (%)) | |

| > High school | 13 (3.5%) |

| High school degree/GED | 33 (17.3%) |

| Some college | 60 (16.0%) |

| College degree | 167 (44.4%) |

| Some graduate | 22 (5.9%) |

| Graduate degree | 72 (19.1%) |

| Race/ethnicity (n [%]) | |

| Caucasian, non-Hispanic | 334 (88.8%) |

| Hispanic | 25 (6.6%) |

| African-American | 4 (1.1%) |

| American Indian | 1 (0.3%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9 (2.4%) |

| Multiple | 3 (0.3%) |

| Child w/ASD | |

| Age, years (M [SD]) | 7.90 (2.3) |

| Male (n [%]) | 161 (86%) |

| Intellectual disability (n (%)) | 65 (34.6%) |

| CBCL internalizing behavior problems (M [SD]) | 63.0 (9.6) |

| CBCL externalizing behavior problems (M [SD]) | 60.1 (11.1) |

| SRS-2 total (M [SD]) | 77.8 (10.6) |

Means and standard deviations from CBCL and SRS taken from mother report self-report at Time 1

ASD autism spectrum disorder, SD standard deviation, CBCL t-scores on child behavior checklist internalizing and externalizing subscales, SRS social responsiveness total t-score

Procedure

The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board. Data used in the present study were obtained through parent self-report questionnaires collected at each of the four time points that asked about child functioning and parenting stress, among other family experiences. Mothers and fathers completed these measures independently during 2.5 h home/or lab visits. Parents were paid $50 for their participation in this portion of the study at each time point.

Measures

Parenting Stress

Mothers and fathers completed the Burden Interview (Zarit et al. 1980), which measures personal distress and difficulty associated with parenting and caring for children. Sample items include: “I feel strained in my interactions with my child,” and “I feel stress between trying to give to my child as well as to other family responsibilities, job, etc.” The Burden Interview consists of 29-items, rated on a four-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (extremely). In the present study, the total score was used as a global measure of parenting stress with higher scores indicating greater levels of parenting stress. This measure has been used with parents of children with DD (Greenberg et al. 1993) and ASD (Hartley et al. 2016, 2011) and has demonstrated strong reliability and good concurrent validity in this sample when compared to other self-report measures of parenting stress [Blinded for Review]. Moreover, the Burden Interview has been shown to be sensitive to change across time and in relation to fluctuation in the behavior problems of grown children with ASD (Orsmond et al. 2006). In the present sample, at Time 1, the Cronbach’s alphas for the total score were 0.87 and 0.86 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Child Behavior Problems

The child with ASD’s level of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1½–5 years (preschool form) and ages 6–18 years (school age form) (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). The CBCL has been widely in the general population (Achenbach 2009) and children with ASD (Mazefsky et al. 2011) in the assessment of child behavior problems and emotional difficulties. Items on the CBCL are rated on a three-point Likert scale (0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = Very true or often true), and create a Total Internalizing Behavior Problem and Total Externalizing Behavior Problem t-score (M = 50 and SD = 10), which were analyzed in the present study. The CBCL has been shown to have strong discriminant, convergent, and predictive validity, as well as high inter-rater between mothers and fathers and strong test-retest reliability (Achenbach and Rescola 2000, 2001). For the preschool form, at Time 1, the Total Internalizing Behavior Problem subscale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 for mothers and 0.84 for fathers; the Total Externalizing Behavior Problem subscale had an alpha score of 0.93 for mothers and 0.92 for fathers. Alpha coefficients for the school-age form at Time 1 were 0.85 on the Total Internalizing Behavior Problems subscale for both mothers and fathers; the Externalizing Behavior Problems subscale had an alpha coefficient of 0.90 for mothers and 0.89 for fathers. The CBCL has been found to capture change across time and in relation to referred and nonreferred samples of children with anxiety disorders and externalizing disorders (Nakamura et al. 2009).

Autism Symptoms

Severity of the child’s ASD symptoms was assessed via the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2; Constantino and Gruber 2012). The SRS is a 65-item measure that assesses the level of social impairment associated with ASD. Respondents are asked to rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Not true, 2 = Sometimes true, 3 = Often true, and 4 = Almost always true). The Total raw score for the SRS-2 ranges from 0 to 195, with higher scores indicating a higher severity of impairment. The internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and test-retest reliability of the SRS-2 has been shown to be strong (Constantino and Gruber 2012). Additionally, the SRS-2 has demonstrated criterion validity with the ADI-R, with correlations between 0.52 and 0.79 (Constantino and Gruber 2012). The SRS has been shown to clinically differentiate between typically developing populations and populations with ASD, and to change in response to intervention (Constantino et al. 2009). In the present sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the SRS-2 Total score was 0.87 for mothers and 0.85 fathers, respectively.

Data Analytic Plan

Boxplots and descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of study variables. Paired sample t-tests were then used to examine mother-father, within-couple, differences in main study variables across T1-T4. The main study question was examined using three multi-group cross-lag panel analyses conducted in structural equation modeling (SEM) in MPlus software (Muthen and Muthen 2012). Specifically, SEM models examined the possible bidirectional relations between parenting stress and the child with ASD’s internalizing behavior problems, externalizing behavior problems and ASD symptoms from one time point to the next, while controlling for previous individual differences between constructs across the four discrete measurement occasions (T1-T4). Mother reported variables (parenting stress and child functioning) were utilized in the models examining mother effects and father reported variables (parenting stress and child functioning) were used in models examining father effects. Models examined the effect of the preceding time point (i.e., 12 months earlier). Means and standard deviations for key measures at each time point are included in Table 2. In order to separately examine effects for mothers and fathers, a dichotomous grouping variable was created (mothers=0 and fathers = 1). The three multi-group cross-panel SEM models each focused on one of the domains of child functioning: internalizing behavior problems, externalizing behavior problems, and ASD symptoms. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to account for missing data (Little 2013) missing at random across the four time-points. Multiple fit indices were examined to assess the overall fit of the data. The Chi square statistic, a global fit index, was used in addition to the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) with values between 0.05 and 0.08 indicating a measure of close fit and values less than 0.08 indicating adequate fit. Further, incremental fit indices such as the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were also examined. For CFI and TFI, values above 0.90 are considered acceptable fit values (Hu and Bentler 1999; Little 2012).

Table 2.

Means for predictor and outcome variables by parent gender

| Variable | Mothers (M/SD) | Fathers (M/SD) | T value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting stress | |||

| Time 1 | 22.71 (8.8) | 20.59 (8.0) | 3.16** |

| Time 2 | 22.59 (9.0) | 20.45 (8.3) | 2.88** |

| Time 3 | 22.76 (9.0) | 19.89 (9.0) | 3.15** |

| Time4 | 23.02 (9.9) | 20.76 (9.1) | 2.23* |

| Child externalizing behaviors | |||

| Time 1 | 60.05 (11.1) | 59.62 (10.3) | 0.68 |

| Time 2 | 57.07 (11.0) | 57.76 (10.1) | − 0.87 |

| Time 3 | 56.60 (10.7) | 56.93 (10.2) | − 0.41 |

| Time 4 | 56.56 (10.6) | 56.69 (11.2) | − 0.16 |

| Child internalizing behaviors | |||

| Time 1 | 62.99 (9.6) | 61.97 (9.4) | 1.37 |

| Time 2 | 61.14 (10.2) | 60.64 (9.2) | 0.60 |

| Time 3 | 61.15 (9.5) | 59.43 (9.7) | 1.64 |

| Time 4 | 61.30 (9.2) | 60.65 (9.2) | 0.71 |

| Child ASD symptoms | |||

| Time 1 | 77.84 (10.6) | 76.23 (9.9) | 2.25* |

| Time 2 | 75.45 (10.3) | 74.15 (10.7) | 1.53 |

| Time 3 | 75.58 (10.9) | 73.41 (11.6) | 2.33* |

| Time 4 | 74.82 (11.7) | 74.10 (11.2) | 0.83 |

ASD autism spectrum disorder

p < .05;

p < .01

Results

Measures of child functioning and parenting stress had a normal distribution, without skew. Paired sample t-tests indicated a significant difference between mother and father report of parenting stress at T1 (t = 3.16, p < 0.01), T2 (t=2.88, p = 0.01), and T3 (t=3.15, p< 0.01), and T4 (t = 2.23, p = 0.03). At all time-points, mothers reported higher parenting stress than fathers. There were no significant differences between mother and father report of child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems across the four time points. In terms of ASD symptoms, mothers and fathers differed on their reports at T1 (t = 2.25, p < 0.05) and T3 (t = 6.11, p < 0.001); there were no significant mother-father differences at the other time points. The results of the three cross-lagged models testing the bidirectional effects parenting stress and child functioning are described below. Based on suggestions from initial modification indices, additional lagged paths were added to all three models. Paths for T1 predicting T3 and T2 predicting T4 were added for parenting stress and internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, and ASD symptoms. There were significant lagged effects for both mothers and fathers in terms of parenting stress and child internalizing behavior problems (see Table 3). There were also significant lagged effects for mothers and fathers with regards to parenting stress and externalizing behavior problems (Table 4) and ASD symptoms (Table 5). Cross-effects for all models remained significant despite the addition of lagged paths. The most parsimonious model was used since additional lagged paths did not produce a significant improvement in model fit. Final standardized estimates for each final model are described below.

Table 3.

Panel analysis for mother and father parenting stress and child internalizing behavior problems

| Time point | β mother report (SE) | β father report (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-effects | Internalizing behavior problems → Later parenting stress | |

| 1→2 | 0.09+ | 0.06 |

| 2→3 | − 0.05 | 0.08 |

| 3→4 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Parenting stress → Later internalizing behavior problems | ||

| 1→2 | 0.20** | 0.29*** |

| 2→3 | 0.21** | 0.08 |

| 3→4 | 0.09 | 0.19* |

| Lagged-effects Internalizing behavior | ||

| 1→3 | 0.35*** | 0.09 |

| 2→4 | 0.25*** | 0.43*** |

| Parenting stress | ||

| 1→3 | 0.38*** | 0.23** |

| 2→4 | 0.33*** | 0.26* |

Values reported in this table are standardized estimates

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Table 4.

Panel analysis for mother and father parenting stress and child externalizing behavior problems

| Time point | β mother report (SE) | β father report (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-effects | Externalizing behavior problems → later parenting stress | |

| 1→2 | 0.08+ | − 0.08+ |

| 2→3 | 0.04 | − 0.03 |

| 3→4 | 0.07 | 0.20*** |

| Parenting stress → later externalizing behavior problems | ||

| 1→2 | 0.21** | 0.12 |

| 2→3 | 0.36** | 0.16* |

| 3→4 | − 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Lagged-effects Externalizing behavior | ||

| 1→3 | 0.42*** | 0.21** |

| 2→4 | 0.18** | 0.34*** |

| Parenting stress | ||

| 1→3 | 0.35*** | 0.24** |

| 2→4 | 0.32*** | 0.21* |

Values reported in this table are standardized estimates

p< 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01,

p< 0.001

Table 5.

Panel analysis for mother and father parenting stress and child ASD symptoms

| Time point | β mother report (SE) | β father report (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-effects | ASD symptoms → later parenting stress | |

| 1→2 | 0.07 | 0.12** |

| 2→3 | 0.09+ | 0.00 |

| 3→4 | 0.14** | 0.05 |

| Parenting stress → ASD symptoms | ||

| 1→2 | 0.15* | 0.18* |

| 2→3 | 0.13+ | 0.25** |

| 3→4 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Lagged-effects ASD symptoms | ||

| 1→3 | 0.41*** | 0.28*** |

| 2→4 | 0.22** | 0.41*** |

| Parenting stress | ||

| 1→3 | 0.37*** | 0.26*** |

| 2→4 | 0.32*** | 0.21* |

Values reported in this table are standardized estimates

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

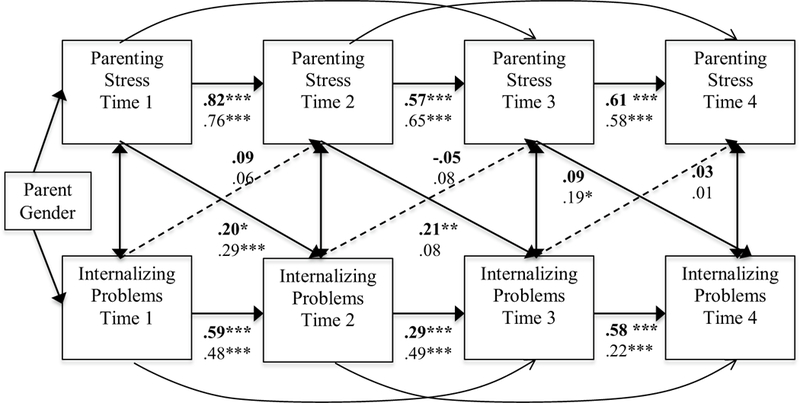

Child Internalizing Behavior Problems

Table 3 displays parameter estimates for cross-lagged effects between parenting stress and child internalizing behavior problems. Model fit indices for parenting stress and child internalizing behavior problems demonstrated fair fit: χ2 (32) = 43.96, p = 0.08, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, and RMSEA = 0.05. Cross-lagged panel analysis for the model using mother-report data demonstrated high stability across all time-points for parenting stress (T1-T2: β = 0.82, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β = 0.57, p < 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.61, p < 0.001) and child internalizing behavior problems (T1-T2: β=0.59, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β=0.29, p < 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.58, p < 0.001). Figure 1 shows cross-lagged effects for mother-report data of parenting stress and child internalizing behavior problems. Cross-lagged panel analysis for the model using father-report data also showed adequate stability across time points for parenting stress (T1-T2: β = 0.76, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β=0.65, p < 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.58, p < 0.001) and internalizing behavior problems (T1-T2: β = 0.48, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β = 0.49, p < 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.22, p < 0.01). Figure 1 shows cross-lagged effects for father-report data of parenting stress and child internalizing behavior problems. As shown in Table 3, there were no significant cross-lagged effects from child internalizing behavior problems to later parenting stress for mothers or fathers. Although, there was a trend-level cross-lagged effect from T1 child internalizing behavior problems to T2 parenting stress in mothers (β = 0.09, p = 0.07). In contrast, there were several significant cross-lagged effects from early parenting stress to later child internalizing behavior problems for both mothers (T1-T2: β = 0.20, p = 0.01; T2-T3: β = 0.21, p = 0.01) and fathers (T1-T2: β = 0.29, p < 0.001; T3-T4: β = 0.19, p = 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Cross-lag model for child internalizing behavior problems and parenting stress. Bold values displayed on top are mothers and non-bold values on bottom are fathers. Significant effects are marked in solid lines if an effect was present for mothers, fathers, or both. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

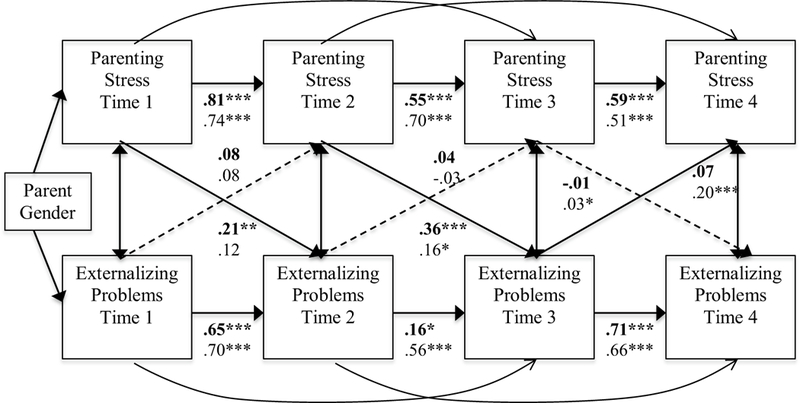

Child Externalizing Behavior Problems

Model fit for the multi-group cross-lagged panel SEM examining parenting stress and externalizing behavior problems was adequate: χ2 (32) = 31.18, p = 0.50, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, and RMSEA = 0.00. Figure 2 shows the cross-lagged model for mothers. The model demonstrated stability effects across all time-points for parenting stress (T1-T2: β = 0.81, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β = 0.55, p < 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.59, p < 0.001), and child externalizing behavior problems (T1-T2: β = 0.65, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β = 0.16, p = 0.05; and T3-T4: β = 0.71, p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the cross-lagged model for fathers. The model showed high stability across all time points for parenting stress (T1-T2: β = 0.74, p < 0.001; T2-T3: β = 0.70, p < 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.51, p < 0.001) and externalizing behavior problems (T1-T2: β = 0.70, p< 0.001; T2-T3: β = 0.56, p< 0.001; and T3-T4: β = 0.66, p < .0.001). Mother and father report crossed-lag effects from T1 to T4 are listed in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, T3 child externalizing behavior significantly predicted parenting stress at T4 for fathers. There were also trend-level cross-lagged effects from T1 child externalizing behavior problems to T2 parenting stress for mothers (β = 0.08, p = 0.06) and fathers (β = 0.08, p = 0.07). In the opposite direction, there were significant cross-lagged effects from parenting stress to later child externalizing behavior problems for mothers from T1 to T2 (β = 0.21, p = 0.01) and T2 to T3 (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). There was a significant cross-lagged effect from T2 parenting stress to T3 child externalizing behavior problems for fathers (T2-T3: β = 0.16, p = 0.03).

Fig. 2.

Cross-lag model for child externalizing behavior problems and parenting stress. Bold values displayed on top are mothers and non-bold values on bottom are fathers. Significant effects are marked in solid lines if an effect was present for mothers, fathers, or both. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

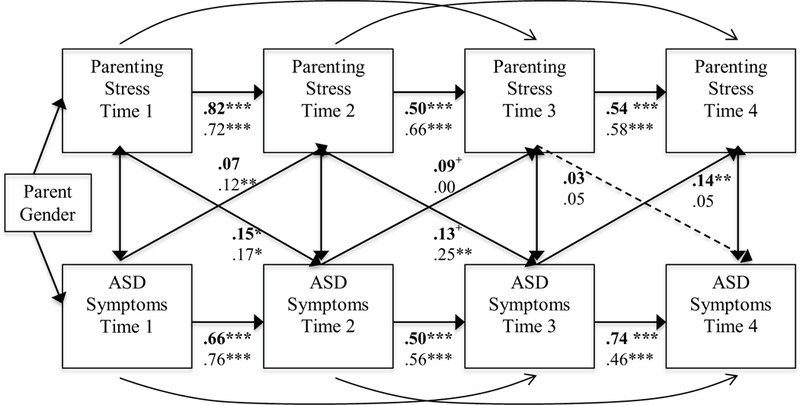

ASD Symptoms

Table 5 displays the estimates for cross-lagged effects between parenting stress and child ASD symptoms. Results indicated good fit to the data: χ2 (32) = 50.14, p = 0.02, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, and RMSEA = 0.05 (CI = 0.02–0.08). Parenting stress was adequately stable for mothers and fathers across time points (mother T1-T2: β = 0.82, p < 0.001, T2-T3: β = 0.50, p < 0.001, T3-T4: β = 0.54, p < 0.001; father T1-T2: β = 0.72, p < 0.001, T2-T3: β = 0.66, p < 0.001, T3-T4: β = 0.58, p < 0.001). Child ASD symptoms were also stable across time points (mother T1-T2: β = 0.66, p < 0.001, T2-T3: β = 0.41, p < 0.001, T3-T4: β = 0.53, p < 0.001; father T1-T2: β = 0.76, p < 0.001, T2-T3: β = 0.56, p < 0.001, T3-T4: β = 0.46, p < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 3, there were significant cross-lagged effects from early child ASD symptoms to later parenting stress in mothers at two time points (T2-T3: β = 0.09, p = 0.06, T3-T4: β = 0.14, p < 0.01). There was also a significant cross-lagged effect from T1 child ASD symptoms to T2 parenting stress for fathers (T1-T2: β = 0.12, p = 0.01). In the opposite direction, there was a significant cross-lagged effect from T1 parenting stress to T2 child ASD symptoms for mothers and fathers (mother: β = 0.15, p = 0.04; father: β=0.17, p=0.03). There was also a cross-lagged effect from T2 parenting stress to T3 child ASD symptoms for fathers (β = 0.25, p < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Cross-lag model for autistic symptoms and parenting stress. Bold values displayed on top are mothers and non-bold values on bottom are fathers. Significant effects are marked in solid lines if an effect was present for mothers, fathers, or both. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Few longitudinal studies have examined the potential bidirectional associations between parenting stress and child functioning in families of children with ASD (e.g., Zaidman- Zait et al. 2014). Instead, it is generally assumed that this pattern of associations flows in only one direction; specifically, that the child with ASD’s behavior problems and ASD symptoms contribute to high parenting stress (e.g., Estes et al. 2013). Yet in other studies, parenting stress has been found to predict greater increases in child behavior problems at a later time point, but not vice versa (Osborne and Reed 2009). It is evident from the literature that the strength and direction of these associations may vary on account of methodological approaches and sample characteristics. The current study employed a multi-group cross-lagged panel design to examine the directional association between parenting stress and three domains of child functioning—ASD symptoms, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems—across four time points, spanning 3 years, in families of children with ASD who were in mid to late childhood. The study also built on previous studies by simultaneously evaluating and comparing the direction of effects for mothers versus fathers of children with ASD.

Overall, results from the study support a transactional model (Hastings 2002; Sameroff 2009), in which there are bidirectional associations between parenting stress and the behavior problems and ASD symptoms of children with ASD. However, the direction of effects between parenting stress and child functioning was contingent on domain of child functioning and changed across time. In regards to child internalizing behavior problems (e.g., social withdrawal and depressed mood), we found a parent-driven pattern. Specifically, parenting stress positively predicted later increases in internalizing behavior problems in children with ASD from one time point to the next, but not vice versa. This pattern of parent-driven effects occurred in both mothers and fathers, but was most prominent in mothers of children with ASD. A similar finding was reported by Zaidman-Zait et al. (2014) in their sample of young children with ASD. Thus, the internalizing behavior problems of children with ASD appear to be triggered by high parenting stress across middle to late childhood. In particular, high parenting stress in mothers may lead to increases in the child with ASD’s internalized behavior problems given findings that mothers often experience greater stress due to differences in role specialization (i.e., caregiver demands related to child care) in families of children with ASD (Hartley et al. 2014).

In contrast to child internalizing behavior problems, we detected a pattern of associations between child externalizing behavior problems and ASD symptoms and parenting stress that resulted in separate effects for mothers and fathers of children with ASD and differed across time points. In regards to child externalizing behavior problems, early on, parenting stress led to increases in child externalizing behavior problems in mothers and fathers of children with ASD. This pattern suggests that a context of high parenting stress may not only lead to child internalizing behavior problems such as withdrawal and avoidance, but also to child externalizing behavior problems such as aggression and impulsivity in children with ASD. In the opposite direction, child externalizing behavior problems led to increases in parenting stress in fathers of children with ASD at the last time point. Thus, with increasing age, the externalizing behaviors of older children with ASD may become increasingly irksome and difficult to manage for fathers. It is not clear why this same effect was not seen in mothers. In previous studies on children with ASD and adolescents with ASD, fathers reported having more difficulty than mothers setting limits and managing difficult child behaviors (Falk et al. 2014). These difficulties may be especially triggered by externalizing child behaviors and become more prominent as the son or daughter with ASD ages.

In our sample, child ASD symptoms led to increases in parenting stress for mothers and fathers of children with ASD, with these child-driven effects stronger earlier on for fathers and later on for mothers. Thus, unlike child behavior problems (both internalizing and externalizing), child ASD symptoms drove increases in parenting stress early on in the study. Child ASD symptom severity has been found to predict parenting stress in previous studies of young children with ASD (Estes et al. 2009, 2013), suggesting that parents may be particularly distressed by ASD symptoms during early to middle childhood. In the opposite direction, in early time points in our study, parenting stress in mothers and fathers also positively predicted later child ASD symptoms. Thus, in a reciprocal process, parents may be stressed by their child’s ASD symptoms, which in turn, alters parenting responses in ways that increase the severity of child ASD symptoms.

In general, parenting stress appeared to have a lower impact on the functioning of children with ASD at later rather than earlier time points in our study. It may be that contexts other than the family have an increasing influence on the functioning of children with ASD into older childhood and emerging adolescence. Indeed, in previous studies the influence of school and peers on providing social support in relation to emotional problems has been shown to increase during adolescence (Helsen et al. 2000; Teacher-Ryan and Patrick 2001). Overall, mother and father parenting stress and the child’s ASD symptoms, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems remained moderately stable across 3 years, which is consistent with previous studies (Baker et al. 2003; Lecavalier et al. 2006; Zaidman-Zait et al. 2014). Thus, parents who initially had high parenting stress generally continued to have high stress across the 3 years. Similarly, children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and ASD symptoms demonstrated moderate stability across the 3 years. Although mothers reported a higher level of parenting stress than fathers, at a within-couple level, mother and father ratings of child ASD symptoms, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems were largely comparable at all time points. However, there were mother-father differences in report of child ASD symptoms, which has also been seen in previous studies (Falk et al. 2014), and may reflect differences between mothers and fathers in time spent in childcare and unique parenting experiences with their child with ASD (Hartley et al. 2011).

There were several strengths to the present study. The study is one of the few to separately assess mother and father reported measures of child functioning and parenting stress in a longitudinal design, and the first to examine bidirectional effects related to three domains of child functioning (i.e., ASD symptoms in addition to internalizing and externalizing behavior problems). Standardized measures of child functioning were obtained separately from mothers and fathers. The study also has limitations. Shared method variance (i.e., single and same reporter) on measures of parenting stress and child functioning is a concern. Parents experiencing higher parenting stress may be more likely to negatively rate their child’s functioning. Additionally, though significant differences between mother and father reports of autism symptoms emerged over the course of the study, measures of child functioning may not be sensitive to naturally occurring variation within children’s home environments and changing contexts over time (e.g., school environments), both of which contribute to changes in child behavior (Blair et al. 2014). Though the analytic approach used in this study allowed us to “control” for previous levels of these variables, they limit our ability to model change in these constructs over time and account for unobserved confounds (e.g., parent well-being, number of children, and support services) that may also account for variation in children’s behavioral functioning and association between parenting and child functioning. Future research should include self-report of internalizing and externalizing functioning for older children, and/or other methods of measurement (e.g., physiological measures), to more fully capture experiences (e.g., anxious thoughts) not easily observable by parents. The study sample was largely White European and of middle socio-economic status, which limits the generalizability of findings. Children with ASD were also largely male (86%). Females with ASD are argued to be under-identified and under-represented in research (Kreiser and White 2014), and have been shown to present with a slightly different profile of ASD symptoms and co-occurring behaviors (Solomon et al. 2012). It is possible that our measures were less sensitive at capturing the functioning of females with ASD and/or the pattern of associations between parenting stress and child functioning seen in the current study may not reflect that of families of females with ASD. In addition, only families with two co-residing parents were recruited for the study. Thus, findings may not generalize to those of single-parent families. Finally, the sample size did not allow us to examine how bidirectional effects between parenting stress and child functioning may differ based on family characteristics such as child gender or ID status or parent social support, or family major life events (e.g., moving, parent health condition, parent new job).

Implications and Future Directions

Findings from the current study have important implications for interventions and supports for children with ASD and their families. Family-based interventions that are directed at both parents and children with ASD may be optimal given the reciprocal ties between parenting stress and child functioning. For example, such family-based interventions could include parent training to teach parents how to cope with parenting stress (e.g., mindfulness practices or relaxation strategies) and how to respond to challenging child behaviors in adaptive ways. Indeed, mindfulness-based intervention strategies have found to reduce parent psychological distress in families of children with ASD (Dykens et al. 2014; Ferraioli and Harris 2013; Lunsky et al. 2017). Moreover, parents could be educated about the domains of child functioning that trigger of parenting stress, and at what child developmental stages. In turn, parent trainings could educate parents on ways to avoid a negative feedback loop whereby parenting stress leads to negative parenting responses that inadvertently reinforce challenging child behaviors. Indeed, parenting stress in both mothers and fathers appeared to be a critical driver of increases in child ASD symptoms, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems especially in middle to older childhood.

Future research should examine variables that moderate or mediate the association between parenting stress and the functioning of children with ASD. In terms of parent characteristics, moderating or mediating variables may include parents’ marital relationship, parenting practices, and support resources. In terms of child characteristics, the child’s ID status and gender may influence the link between parenting stress and child functioning across time. Gender differences in particular, as they relate to the presentation of pathology and the autism phenotype is an area in need of further research. Research has yielded mixed findings suggesting subtle differences in autism symptomatology among boys and girls, with boys evidencing more restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs) and deficits in social reciprocity (Hartley and Sikora 2009). While gender differences in social and communication skills may level off in childhood and adolescence, boys may continue to demonstrate greater externalizing behavior problems and social problems compared to girls with ASD, who may present with milder RRBs and more internalizing behavior problems as they get older (Hartley and Sikora 2009; Mandy et al. 2012). Future research should focus on examining sex differences as they relate to pathology over time in order to improve the detection and treatment of girls with ASD. Additionally, future research should consider which types of ASD symptoms (e.g., repetitive and restricted behaviors vs. social communication impairments) and internalizing (e.g., inattention vs. depressed mood) and externalizing behavior problems (e.g., aggression vs. hyperactivity) that are most strongly linked to parenting stress. While this study was able to detect associations between these variables over time, the ability of measures to capture subtle changes in child functioning in response to the developmental changes in behavior and contextual influences necessitates further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was based on a longitudinal study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) R01 (R01MH099190); S. Hartley, P.I.). The study was supported by core grant to the Waisman Center from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54 HD090256 to A. Messing). Additional support was also provided by the Waisman Center Postdoctoral Training Program in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities National Institutes of Child and Human Development (NICHD) T32 (T32HD07489). We are indebted to our colleagues and students and to the children and families who participated in this research.

Funding This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) R01MH099190, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) U54HD090256, and National Institute of Child and Human Development (NICHD) T32HD07489.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent It was obtained by all participating families in this study and obtained individually by participants throughout each visit.

References

- Achenbach TM (2009). Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Development, findings, theory, and applications. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center of Children, Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fifth Ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C, & Low C (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(4–5), 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PR (2006). The impact of child symptom severity on depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: The mediating role of stress proliferation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(5). 685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC, & Berry DJ (2014). Two approached to estimating the effect of parenting on the development of executive function in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Abbachi AM, Lavesser PD, Reed H, Givens L, Chiang L, & Todd RD (2009). Developmental course of autistic social impairment in males. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 127–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, & Gruber CP (2012). The social responsiveness scale manual. Second Edition (SRS-2). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska A, & Pisula E (2010). Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(3), 266–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NO, & Carter AS (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Fisher MH, Taylor JL, Lambert W, & Miodrag N (2014). Reducing distress in mothers of children with autism and other disabilities: A randomized trial. Pediatrics, 134(2), 454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Munson J, Dawson G, Koehler E, Zhou XH, & Abbott R (2009). Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism, 13(4), 375–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Olson E, Sullivan K, Greenson J, Winter J, Dawson G, & Munson J (2013). Parenting-related stress and psychological distress in mothers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain and Development, 35(2), 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk NH, Norris K, & Quinn MG (2014). The factors predicting stress, anxiety, and depression in the parents of children with autism. Journal on Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3185–3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraioli SJ, & Harris SL (2013). Comparative effects of mindfulness and skills-based parent training programs for parents of children with autism: Feasibility and preliminary outcome data. Mindfulness, 4(2), 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, & Greenley JR (1993). Aging parents of adults with disabilities: The gratifications and frustrations of later-life caregiving. The Gerontologist, 33(4), 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ (2011). Why early intervention works: A systems perspective. Infants and Young Children, 24(1), 6–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, & Floyd FJ (2011). Marital satisfaction and parenting experiences of mothers and fathers of adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(1), 81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Mihaila I, Otalora-Fadner HS, & Bussanich PM (2014). Division of labor in families of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Family Relations, 63(5), 627–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Papp LM, & Bolt D (2016). Spillover of marital interactions and parenting stress in families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 00, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, & Sikora DM (2009). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: An examination of developmental functioning, autistic symptoms, and coexisting behavior problems in toddlers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(12), 1715–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP (2002). Parental stress and behaviour problems of children with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(3), 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP (2003). Child behaviour problems and partner mental health as correlates of stress in mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(4–5), 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, & Watson SL (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3). 629–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsen M, Vollebergh W, & Meeus W (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 29(3), 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaat AJ, & Lecavalier L (2013). Disruptive behavior disorders in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the prevalence, presentation, and treatment. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(12), 1579–1594. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiser NL, & White SW (2014). ASD in females: Are we overstating the gender difference in diagnosis? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(1), 67–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, Leone S, & Wiltz J (2006). The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(3), 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little PTD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, & Bishop S (2012). Edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part I) In Modules 1–4 (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second). Torrance: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, Heemsbergen J, Jordan H, Maw- hood L, & Schopler E (1989). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: A standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19, 185–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounds J, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, & Shattuck PT (2007). Transition and change in adolescents and young adults with autism: Longitudinal effects on maternal well-being. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112(6), 401–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunsky Y, Hastings RP, Weiss JA, Palucka AM, Hutton S, & White K (2017). Comparative effects of mindfulness and support and information group interventions for parents of adults with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(6), 1769–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandy W, Chilvers R, Chowdhury U, Salter G, Seigal A, & Skuse D (2012). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder:Evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1304–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Anderson R, Conner CM, & Minshew N (2011). Child behavior checklist scores for school-aged children with autism: Preliminary evidence of patterns suggesting the need for referral. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(1), 31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, & Muthén LK (2012). Software Mplus Version 8.0. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Ebesutani C, Bernstein A, & Chorpita BF (2009). A psychometric analysis of the child behavior checklist DSM- oriented scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 178–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, & Baker BL (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond GI, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, & Krauss MW (2006). Mother-child relationship quality among adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111(2), 121–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne LA, & Reed P (2009). The relationship between parenting stress and behavior problems of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Exceptional Children, 76(1), 54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A (2009). The transactional model. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Miller M, Taylor SL, Hinshaw SP, & Carter CS (2012). Autism symptoms and internalizing psychopathology in girls and boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(1), 48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teacher- Ryan AM, & Patrick H (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents’ motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437–460. [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, & Scahill L (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 216–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman AC, Mawdsley HP, & Hauser-Cram P (2015). Parenting stress and child behavior problems within families of children with developmental disabilities: Transactional relations across 15 years. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 264–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidman-Zait A, Mirenda P, Duku E, Szatmari P, Georgiades S, Volden J, & Fombonne E (2014). Examination of bidirectional relationships between parent stress and two types of problem behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1908–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, & Bach-Peterson J (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20(6), 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]