Abstract

Accumulation of microtubule associated protein tau in the substantia nigra is associated with several tauopathies including progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). A number of studies have used mutant tau transgenic mouse model to mimic the neuropathology of tauopathies and disease phenotypes. However, tau expression in these transgenic mouse models is not specific to brain subregions, and may not recapitulate subcortical disease phenotypes of PSP. It is necessary to develop a new disease modeling system for cell and region-specific expression of pathogenic tau for modeling PSP in mouse brain. In this study, we developed a novel strategy to express P301L mutant tau to the dopaminergic neurons of substantia nigra by coupling tyrosine hydroxylase promoter Cre-driver mice with a Cre-inducible adeno-associated virus (iAAV). The results showed that P301L mutant tau was successfully transduced in the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra at the presence of Cre recombinase and iAAV. Furthermore, the iAAV-tau-injected mice displayed severe motor deficits including impaired movement ability, motor balance, and motor coordination compared to the control groups over a short time-course. Immunochemical analysis revealed that tau gene transfer significantly resulted in loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive dopaminergic neurons and elevated phosphorylated tau in the substantia nigra. Our development of dopaminergic neuron-specific neurodegenerative mouse model with tauopathy will be helpful for studying the underlying mechanism of pathological protein propagation as well as development of new therapies.

Keywords: adeno-associated virus, microtubule-associated protein tau, neurodegenerative diseases, substantia nigra, tauopathies

INTRODUCTION

Abnormal accumulation of the microtubule-associated protein tau is the primary neuropathological hallmark in several neurodegenerative diseases known as tauopathies such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Scheltens et al., 2016), corticobasal degeneration (CBD) (Ali and Josephs, 2018), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) (Williams and Lees, 2009; Boxer et al., 2017) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (Cairns et al., 2007; Ghetti et al., 2015). Growing evidence demonstrates that in all of these diseases toxic tau aggregates are expressed in the substantia nigra (SN) and other sensorimotor coordinating regions where the majority of the dopaminergic neurons in the brain are located (Dickson et al., 2010; Kovacs, 2015). There is a gradual deterioration of these cells causally related to tau abnormalities, which can contribute to progressive clinical symptoms of diseases including movement difficulty, dementia, and supranuclear gaze palsy (Fahn et al., 2011; Ghetti, et al. 2015).

Mutations in the tau gene are strongly linked to tauopathies including FTD, CBD, PSP and AD (Coppola et al., 2012; Kouri et al., 2014; Boxer et al., 2017). They can either alter the sequence of tau, or change the alternative splicing sites, which might cause loss of functions or toxic gain of functions and thereby lead to neurodegeneration (Wang and Mandelkow,2016). Of these mutations, P301L tau is particularly pathogenic as it can accelerate tau aggregation both in vitro and in vivo (Hong et al., 1998; Khlistunova et al., 2006). In addition, a number of studies revealed that transgenic mice expressing P301L tau can develop neurofibrillary tangle-like tau aggregation and behavioral phenotypes, which mimic the phenotypes of neurodegenerative diseases (Lewis et al., 2000; Asai et al., 2014). The tau expression in transgenic mouse models, however, is generally ubiquitous in the brain regions (Asai et al., 2014). To ensure the mutant tau expression will be primarily restricted to dopamine neurons in the SN, we developed specific targeting of P301L tau expression to the SN by coupling tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) promoter Cre-driver mice with Cre-inducible adeno-associated virus (iAAV). We further studied the related movement behaviors in mice and evaluated the causal relationship between tau abnormalities and degeneration of dopaminergic neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male B6.Cg-Tg(TH-Cre)1Tmd/J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (USA) and were bred with C57BL/6 female mice according to the Jackson Laboratory Resource Manual guidelines. These TH-Cre transgenic mice have the rat tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) promoter directing expression of Cre recombinase to catecholaminergic cells, and are useful for studying dopaminergic cell function (Savitt et al., 2005). 20-week-old TH-Cre hemizygous mice were next chosen and subdivided into three groups with similar proportions of males and females for further injections and behavioral tests. The sample size of saline-injected group, GFP-injected group and Tau-injected group for animal behavioral tests is 17, 11, 15, respectively. All animal procedures followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Stereotaxic AAV injections

The DNA pAAV-EF1a-FLEX-mCherry was a gift from Karl Deisseroth (Addgene plasmid # 20299). The mCherry in the construct was replaced with the cDNA of GFP, human WT tau, or the P301L form of human tau (four repeat microtubule-binding domains, 4R2N) using endonuclease sites Nhel and AscI to make AAV-FLEX-GFP, AAV-FLEX-WT tau, or AAV-FLEX-P301L tau plasmids. Of them, AAV-FLEX-GFP and AAV-FLEX-P301L tau plasmids were packaged by SignaGen Laboratories (SignaGen Laboratories, USA) to create recombinant pseudotyped AAV2/6 virus, while AAV-FLEX-WT tau was only used for HEK293 cells transfection in vitro. A unilateral injection of 2 μl containing approximately 1 × 1012 genome copies of AAV was administrated as described (Isingrini, et al. 2017). The experimental group was injected with AAV2/6-Ef1a-FLEX-P301L human tau and the control group was injected with AAV2/6-EF1a-FLEX-GFP or saline using a robotic stereotaxic injection system (Neurostar, Tubingen, Germany) to target the substantial nigra based on the coordinates (AP −3.10, ML −1.12, DV −4.34) shown in Fig. 1B. Mice were anesthetized with 1–5% isoflurane gas combined with oxygen during the surgery.

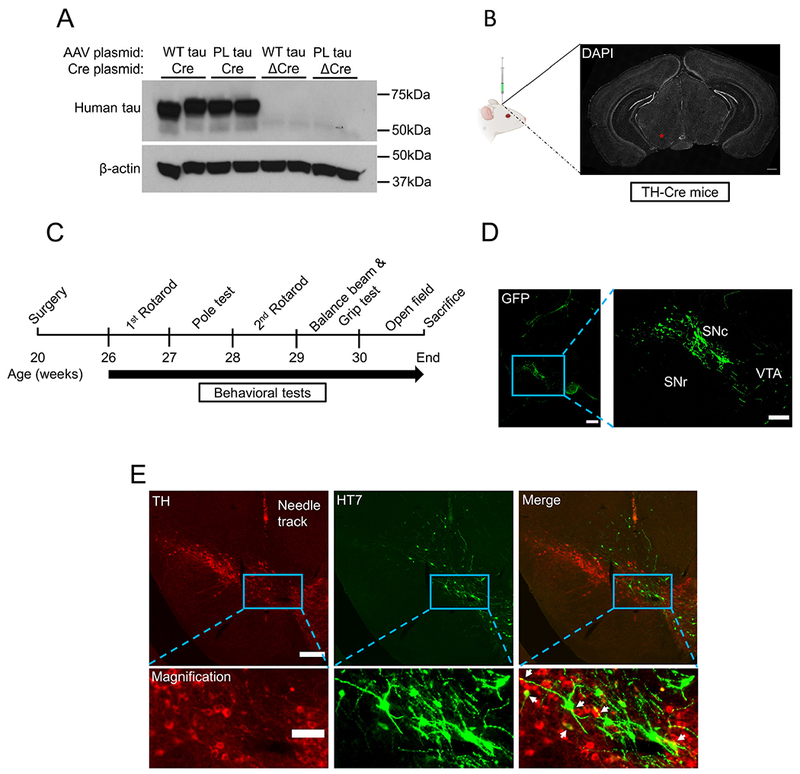

Fig. 1.

iAAV-mediated delivery of transgenes in mouse substantia nigra. (A) In vitro validation of Cre-dependent transgenes expression in HEK293 cells by western blot. Co-transfection of AAV-FLEX-WT tau (positive control) and AAV-FLEX-P301L tau plasmid with Cre expression plasmid showed a robust expression of human tau using monoclonal HT7 antibody. No tau gene expression was observed when Cre was replaced with ΔCre plasmid, which expresses inactive Cre recombinase. (B) Unilateral injection of saline, AAV2/6-FLEX-GFP, or AAV2/6-FLEX-P301L tau in the SN of 20-week-old TH-Cre mice. The injection site (coordinates: −3.10 mm AP, −1.12 mm ML, −4.34 mm DV) is indicated by a red asterisk, where the substantia nigra is located. (C) Experimental paradigm. Mice underwent surgery at postnatal week 20 and behavioral tests were performed from week 26 to week 30 as shown. (D) Expression of Cre-dependent GFP in tyrosine hydroxylase promoter Cre-driver mice. The TH expressing dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA), rather than nondopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), can express GFP fluorescence. (E) Expression of Cre-dependent tau in tyrosine hydroxylase promoter Cre-driver mice. Targeted human P301L tau was specifically immunostained with HT7 antibody in TH cells of the substantia nigra (indicated by white arrowheads). Scale bars: A, 500 μm; C, 200 μm (left) and 100 μm (right); D, 100 μm and 20 μm (magnification).

Behavioral tests

All behavioral tests were performed in an empty testing room within the animal vivarium, during the light cycle between the hours of 9 am–6 pm. For all tests, animals were habituated in the test room for at least 1 hour before the start of testing. A test-free period of 3–5 d was used between behavioral tests. The lighting, humidity, temperature, and ventilation were kept as constant as possible in the testing room. All behavioral analyses were performed in a blinded manner.

Rotarod test.

Latency to fall was measured using a rotarod apparatus at 6 weeks post injection (WPI) and again at 8WPI four times/day for three consecutive days (Jaworski et al., 2009). They were placed such that they were walking away from the user and climbing “up” the spinning spindle. On the first day, the mice were trained by being placed on the rotarod while it is running at a constant 4 rpm for four 90 second runs. On the subsequent testing days, the rotarod was set to accelerate from 4 to 40 rpm in 5 min. The time at which a mouse falls from the rotor onto the plank below was recorded as the latency to fall. There was a 20-minute interval between each trial during which the apparatus was cleaned with 20% EtOH and allowed to completely dry.

Pole test.

The pole test was performed as described with minor modifications (Karuppagounder et al., 2016). Briefly, mice were tested for latency to descend a 55 cm high, 10 mm diameter vertical pole at 7 WPI for five trials/day for four consecutive days. Each mouse was habituated to the pole for the first two days prior to testing. During testing, mice were placed facedown at the top of the pole and allowed to descend after gripping the pole with all four paws. The time between the release of the mouse’s tail to the moment its front paws reach the bedding below was recorded as the latency to descend. The max default value of 120 s was assigned if mice were unable to complete the tasks.

Balance beam test.

Balance beam test was carried out as previously described (Luong et al., 2011). Each mouse was habituated for the first day prior to testing. After training, mice were placed onto a 15 mm-wide, 80 cm-long balance beam and the time to cross the balance was recorded for three trials/day for two consecutive days.

Grip strength test.

Grip strength of mice was tested using a Grip Strength Meter (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) at 9 WPI for four consecutive trials on one day. Mice were held by the base of their tail and allowed to grasp the metal grip grid of the apparatus with only their forelimb paws. They were then pulled back horizontally until the grip was released, and the maximal force achieved was recorded.

Open field test.

Spontaneous locomotor activity was measured using an automated Noldus Ethovision XT apparatus (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands) at 10 WPI (Maeda et al., 2016). Mice were placed in a 50 cm × 50 cm box and their locomotion was tracked for 60 min. The total distance and the average velocity during testing period were measured.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were sacrificed immediately after completion of all behavioral tests. Animals were transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a rate of 10 ml/min for 10 min, followed by an equal volume of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at the same rate. Brains were harvested, post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA and soaked in 15% sucrose solution for one night. Coronal sections were collected from AP −2.6 to −3.6 at a thickness of 30 μm and stamped on glass slides in 10 series. Before staining, antigen retrieval was performed in 10% formic acid for 20 mins at room temperature and rinsed 2 times with PBS. Brain sections were blocked in blocking buffer (4% NGS, 4% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% Triton-X) at room temperature for 1 h. Immunohistochemical staining was further performed using antibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000; Millipore), human tau (HT7, mouse monoclonal, 1:500; ThermoFisher Scientific), phosphorylated tau (AT8 and CP13, mouse monoclonal, 1:500; ThermoFisher Scientific) overnight at 4 °C. On the following day, the primary antibodies were removed and slices were rinsed 3 times with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS. Sections were incubated with the secondary antibodies (Alexa 488 and Alexa 546) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 3 washes with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS. The sections were mounted with ProLong Gold (ThermoFisher Scientific) and cured overnight in darkness for microscopic imaging.

Image capture and TH neurons counting in the SN

Images were captured with a motorized Nikon deconvolution wide-field Epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments, Japan) (Fig. 1B, D and E; Fig. 3A) and Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser microscope (Fig. 3F and G) (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany) using 10×, 20× and 40× objectives. The wide-field images in Figs. 1B, D, E and 3A were automatically assembled by NIS-Elements software. 4 sections evenly spaced throughout the SN per animal with 4 total animals were analyzed for each group displayed (AAV-FLEX-GFP and AAV-FLEX-P301L tau). The number of TH expressing neurons alone or co-stained with GFP or human tau in the SN was quantified using ImageJ software in a blinded manner as described (Grames et al., 2018). The average number of TH neurons per mm2 was finally compared between groups.

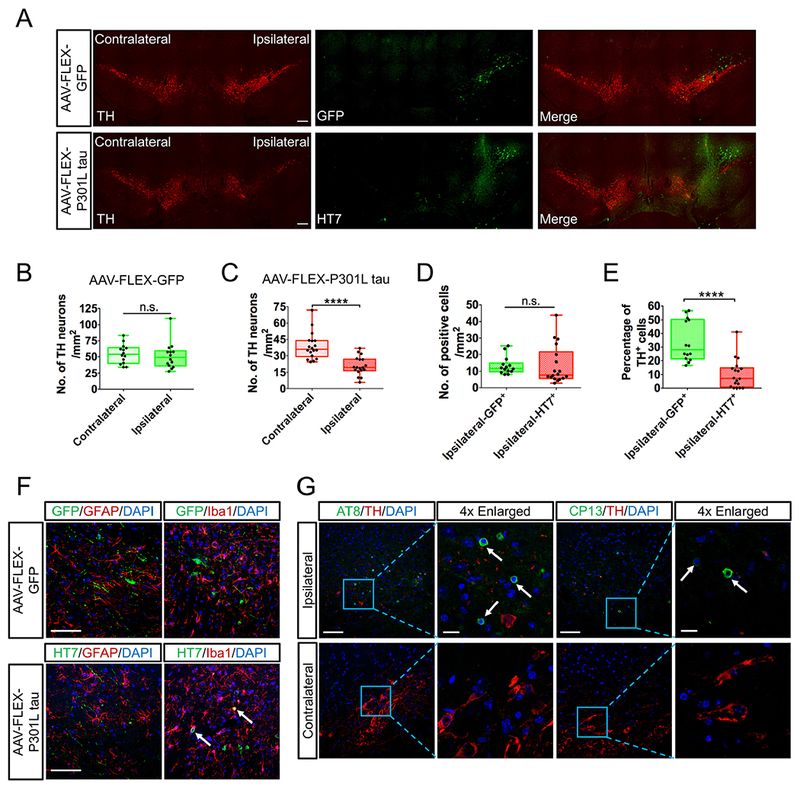

Fig. 3.

P301L tau transfer causes significant loss of TH neurons and degeneration of SN. (A) Immunohistochemistry of tyrosine hydroxylase and transgenes (GFP or P301L tau) in the substantia nigra. TH was preserved in both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides in the GFP-injected mice, whereas P301L tau expression obliterated TH on the ipsilateral side of injection. (B-C) Comparison of total TH positive cells between contralateral and ipsilateral side in SN for AAV-FLEX-GFP (B) and AAV-FLEX-P301L tau (C) group. Tau transfer reduced 50% of TH neurons in the ipsilateral side relative to contralateral side. (D) Number of transduced cells by AAV-FLEX-GFP or AAV-FLEX-P301L tau vector. The number of cells expressing GFP or tau are comparable, suggesting the similar transduction efficiency in each group. (E) Percentage of TH+ GFP+ cells in total GFP+ cells and TH+ HT7+ cells in total HT7+ cells, respectively. Fewer tau positive cells are simultaneously expressing TH, revealing the cytotoxicity of tau in dopaminergic neurons. (C-E) N = 4 animals per group for quantification. (F) Immunohistochemistry of astrocyte stained by GFAP or microglia stained by Iba1 with transgenes (GFP or P301L tau) in the substantia nigra. No transfected cells were co-localized with astrocyte or microglia in the GFP-injected side, whereas some of HT7+ cells were co-localized with Iba1+ microglia (indicated by white arrows), suggesting the engulfment of tau-induced degenerative neurons by microglia. (G) Tau pathology was detected with phosphorylated tau antibodies (AT8 and CP13, indicated by white arrows) in the substantia nigra of Tau-injected ipsilateral side. Scale bars: A, 200 μm; F, 100 μm; G, 100 μm and 20 μm (4 × Enlarged). Data are presented by box and whisker plots which show the median and the 25th to 75th percentiles; ****p < 0.0001, n.s., no significance, using Wilcoxon matched pairs test (B-C) or using Mann–Whitney U test (D-E).

Western blot

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells were co-transfected with 5 μg AAV plasmids and 5 μg Cre plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with a ratio of 1 μg plasmid to 3 μl Lipo2000 according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 2 days, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific). Protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Protein extracts (20 μg) were separated and loaded to 10% SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting using rabbit anti-tau (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse anti-β-actin (1:5000; Millipore) antibodies.

Statistical analysis

All data were assessed for normal distribution by Shapiro–Wilk test. Bartlett’s test was used for equality of variance. We used ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons for statistical tests of behavioral assays, all of which were found meet parametric parameters. For immunohistochemistry results, the data were not normally distributed, therefore we performed the Wilcoxon matched pairs test for dependent samples (Contralateral vs Ipsilateral, Fig. 3B and C) and the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples (GFP vs Tau, Fig. 3D and E) by Prism 6.0 as indicated. P values <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Refined expression of transgenes in SN region by iAAVs in TH-Cre mice

To develop a refined mouse model in which the transgenes were delivered only in the region of interest, we used adult TH promoter Cre-driver mice (age ~20 weeks), which were divided into three groups for further treatment. Under control of the TH promoter, it has been proven that the Cre recombinase protein can be selectively expressed in TH positive neurons in the SN (Grames et al., 2018). Cre-inducible tau gene expression was first validated in human embryonic kidney 293 cells by western blot. Cre recombinase protein flips a non-sense, inverted orientation of transgene to a sense orientation for protein expression in the FLEX-AAV vector (Illiano et al., 2017). Human tau was detected when co-expression of AAV-EFIa-FLEX-WT tau and AAV-EF1a-FLEX-P301L tau plasmid with Cre expression plasmid. In contrast, tau expression was not detected in presence of ΔCre, an inactive version of Cre recombinase (Fig. 1A). Next, animals were then injected with saline, AAV2/6-EF1a-FLEX-GFP (iAAV-GFP) or AAV2/6-EF1a-FLEX-P301L tau (iAAV-tau) unilaterally in the SN with the adapted coordinate (−3.1mm AP, −1.12 mm ML, −4.34 mm DV) (Fig. 1B). Animals were tested for motor behavioral assays from 6 weeks post-injection (WPI) to 10 WPI, after which mice were sacrificed to collect brain tissues (Fig. 1C).

Next, we performed immunostaining to confirm the transgene expression in dopaminergic neurons by injection of iAAV GFP vector. As shown in Fig. 1D, dopaminergic neurons in the SN pars compacta (SNc) are efficiently transduced. Of note, the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which is close to the SN and contains TH+ cells, can also be transduced. In contrast, the iAAV system clearly avoids the nondopaminergic neurons in the SN pars reticulata (SNr), demonstrating the selective expression of the transgene only in the TH-expressing cells (Fig. 1D). Finally, the iAAV-dependent expression of P301L mutant tau was successfully observed in TH+ neurons of the SN using human tau-specific monoclonal antibody HT7 (Fig. 1E). Taken together, a combination of TH-Cre mice with stereotaxic injection of iAAV-tau will successfully induce P301L tau expression in the TH+ dopaminergic neurons of the SN region.

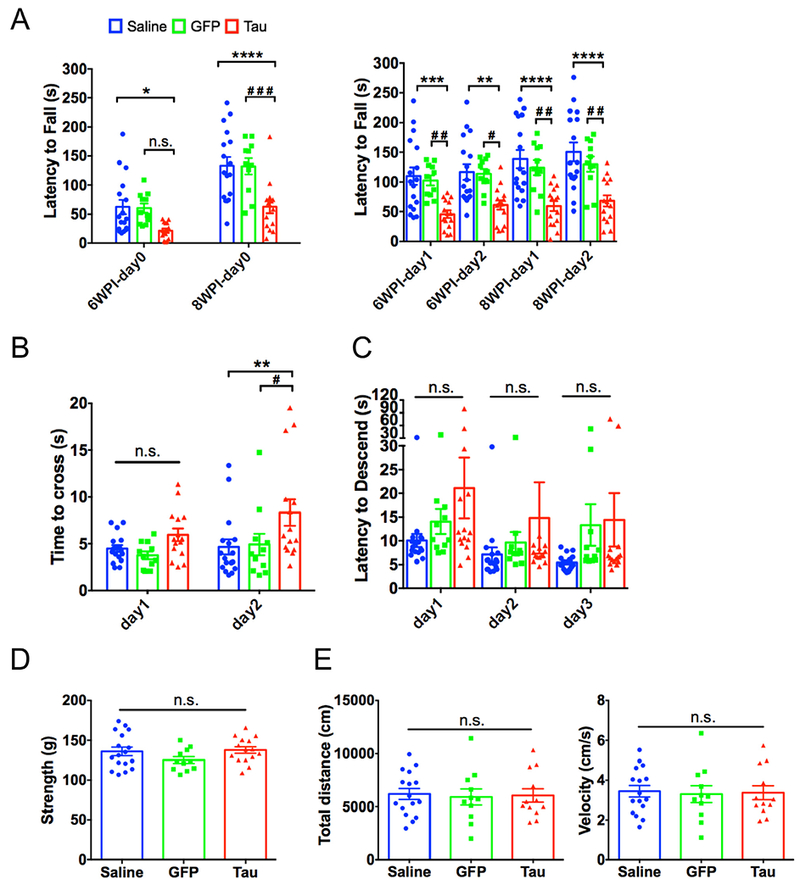

iAAV-mediated transfer of P301L tau to the dopaminergic neurons in the SN region causes motor deficits in TH-Cre mice

In order to evaluate whether mutant tau expression could cause dysfunction of SN, thereby leading to motor deficits (Klein et al., 2008), we performed several motor-related behavioral tests. For the rotarod test, latency to fall was tested for three consecutive days at 6 and 8 WPI (Chew et al., 2015). At day 0 with a constant rotation speed, the time to fall off was decreased in iAAV-P301L tau (Tau)-injected mice compared to the saline- or GFP-injected mice at 6 WPI, and the reduction is more significant at 8 WPI (two-way ANOVA F(2,80) = 15.27, p < 0.0001; Sidak post-hoc comparisons: Saline vs Tau, p = 0.0330 at 6 WPI and p < 0.0001 at 8 WPI; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.0896 at 6 WPI and p = 0.0004 at 8 WPI Fig. 2A). Similarly, in each of the accelerating rotarod tests (day 1 and 2), latency to fall was significantly reduced in Tau-injected mice compared to that in saline- or GFP-injected mice particularly at 8 WPI, indicating a decrease in performance overtime (two-way ANOVA F (2,160) = 40.48, p < 0.0001; Sidak post-hoc comparisons: 6 WPI-day 1: Saline vs Tau, p = 0.0004; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.0071; 6 WPI-day 2: Saline vs Tau, p = 0.0025; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.0140; 8 WPI-day 1: Saline vs Tau, p < 0.0001; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.0016; 8 WPI-day 2: Saline vs Tau, p < 0.0001; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.0028 Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Motor behavioral assays of transgenes targeted mice. (A) Mean latency to fall (s) in the rotarod test with constant speed (4 rpm) at day 0 and accelerating speed at day 1 and 2 (4 to 40 rpm in 5 mins) after 6 weeks post-injection (WPI) and 8 WPI in injected TH-Cre mice. N = 17, 11, and 15 for saline, GFP or Tau group. (B) Time to cross the beam (s) in the balance beam test over 2 consecutive days (day 1 and 2) injected TH-Cre mice. N = 17, 11, and 15 for saline, GFP or Tau group. (C) Latency to descend (s) from the upside of the wooden pole in pole test over 3 consecutive days in injected TH-Cre mice. N = 17, 11, and 15 for saline, GFP or Tau group. (D) The grip strength (g) of injected TH-Cre mice. N = 17, 11, and 15 for saline, GFP or Tau group. (E) Spontaneous locomotor activity in open field of injected TH-Cre mice. N = 16, 11, and 15 for saline, GFP or Tau group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, *p or #p < 0.05, **p or ##p < 0.01, ***p or ###p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, n.s., no significance, using two-way ANOVA with Sidak post-hoc tests (A-C) or using one-way ANOVA with Sidak post-hoc tests (D-E) for multiple comparisons tests.

Furthermore, Tau-injected mice also displayed motor impairments in both the balance beam test and pole test, which are commonly used to assess motor coordination and balance in mice (Illiano et al., 2017; Karl et al., 2003). At day 1 in the balance beam test, Tau-injected mice spent more time crossing the narrow beam than saline- or GFP-injected mice did, although no significance was found (two-way ANOVA F(2,80) = 6.214, p = 0.0031; Sidak post-hoc comparisons: Saline vs Tau, p = 0.5235; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.2754 Fig. 2B). As expected, significantly increased time to cross the beam was observed in Tau-injected mice at test day 2 when compared to the control groups (Sidak post-hoc comparisons: Saline vs Tau, p = 0.0081; GFP vs Tau, p = 0.0358 Fig. 2B). In the pole test, mice were placed on the top of a vertical wooden pole and the time spent to walk down it was recorded (Karuppagounder et al., 2016). There was no difference in the latency to descend between the Tau-injected group and the control groups at every test day (day 1 to 3), but the injection effect was still observed (two-way ANOVA F(2,120) = 3.887, p = 0.0231 Fig. 2C), suggesting the affected performance in Tau-injected mice.

Last, the strength in the grip test was unaltered in Tau-injected mice (one-way ANOVA F(2,40) = 1.705, p = 0.1948 Fig. 2D). The locomotor activity in the open field test was also comparable between the three groups (total distance: one-way ANOVA F(2,36) = 0.0495, p = 0.9517; velocity: one-way ANOVA F (2,36) = 0.0449, p = 0.9561 Fig. 2E). Taken together, these behavioral results show that iAAV-mediated expression of P301L mutant tau in the dopaminergic neurons of the SN caused severe motor deficits in TH-Cre mice.

P301L tau expression leads to significant loss of TH+ cells and tau pathology in the SN

At 10 WPI after completion of all the behavioral assays, brain tissues were collected for immunohistochemical analysis. The SN sections were immunostained for the transgenes (GFP or Tau) and TH as the marker of dopaminergic neurons. In the GFP-injected mice, partial transgenic GFP was also found in TH− neurons, which is likely due to the non-specific Cre expression in TH negative cells in the SN region. In the Tau-injected mice, we observed significant loss of TH+ neurons in the ipsilateral SN region relative to the contralateral SN region (Fig. 3A). In contrast, there was no difference in the number of TH+ cells between the two SN regions in the GFP-injected mice (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that there was around 50% loss of TH+ cells in the Tau-injected ipsilateral SN region relative to the contralateral SN region, whereas there is no difference in GFP-injected ipsilateral SN region relative to the contralateral SN region (TH cells: Ipsilateral-GFP vs Contralateral-GFP, W = 45.00, p = 0.1726; Ipsilateral-Tau vs Contralateral-Tau, Wilcoxon matched pairs test, W = 171.0, p < 0.0001 Fig. 3B and C), which is consistent with the images displayed in Fig. 3A. In addition, there was no difference in the number of total GFP+ and HT7+ cells in the injected side (Ipsilateral-GFP vs Ipsilateral-Tau, Mann-Whitney U test, U (268, 260) = 89.00, p = 0.1670 Fig. 3D). We did, however, find significant reduction of the ratio of HT7+ TH+ cells to total HT7+ cells as compared to that of GFP+ TH+ cells to total GFP+ cells (Ipsilateral-GFP+ vs Ipsilateral-HT7+ , Mann-Whitney U test, U (340, 188) = 17.00, p < 0.0001 Fig. 3E). This result further confirms that expression of mutant tau could result in neuronal degeneration of SN, and loss of TH+ HT7+ cells. These degenerative neurons caused by tau expression might be further engulfed by microglia, as we only observed the co-localization of HT7+ cells with Iba1+ microglia other than GFAP+ astrocyte (Fig. 3F). Finally, increased phosphorylated tau was observed using AT8 (detecting pSer202 and pSer205 tau) and CP13 antibodies (detecting pSer202 tau) in the Tau-injected ipsilateral SN region, suggesting the presence of abnormal posttranslational modification of tau which might lead to tau accumulations (Fig. 3G). No neurofibrillary tangles indicated by Thioflavin-S were found in the Tau-injected mice (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we set out to develop a cell and region-specific tau transgene expression model by combining iAAV vectors with TH-Cre-driver mice in the dopaminergic neurons of SN as a potential PSP mouse model. Clearly, non-specific neuronal transduction was avoided here with Cre-targeted approach along the needle track and in the nondopaminergic neurons such as SNr (Fig. 1D), which were usually transduced by conventional AAV vectors (Rolland et al., 2017). Pinpoint targeting of mutant tau into the dopaminergic neurons in the SN in the mouse was also achieved using pseudotyped recombinant AAVs (rAAV 2/6), which have been emerged as a widely used tool for the delivery of transgenes to neurons of the CNS. Furthermore, under these expression conditions, significant behavioral deficits and some loss of TH-cells in SN were observed after a short interval. Novelty lies on our ability to provide a comprehensive estimation of a mouse model for refined targeting of tau into dopamine neurons in a mouse model. Future studies can be conducted based on our mouse model using different AAV serotypes as well as Cre-drivers for further investigating tau-related pathology development as well as behavioral changes.

Despite the transgene expression was expected in all TH+ cells, we still observed some GFP expression in TH− cells (Fig. 3A). A similar result was also reported in other studies using the TH-Cre driver mice (Savitt et al., 2005). One possibility is that the TH promoter-driven Cre protein expression here is derived from rat, whose expression pattern might not be completely identical to endogenous TH expression in mouse brains even their promoter sequences are highly conserved within mammals (Banerjee et al., 2014). It is also due to the discrepancy between the sensitivity of detecting TH+ cells by immunohistochemistry and the efficiency of TH-Cre induced recombination in the same cells (Savitt et al., 2005; Stuber et al., 2015). For example, Cre-mediated recombination can occur in TH− cells with very weak TH promoter activation (Atasoy et al., 2008). Additionally, the estimated transduction efficiency was not as expected in TH+ neurons within the SN region (Fig. 3D). One explanation is that it is more appropriate to evaluate the transduction efficiency in much earlier time point (for example, one week after injection) to avoid secondary spread of transgene from primary infected cells or loss of infected TH+ cells caused by mutant tau. Another possibility is that the efficiency might also depend on the vector dose, AAV serotype, as well as the promoter strength. Several studies have suggested a robust neuronal transduction efficiency of targeting diseases-related proteins to the SN in rat brains by utilizing AAV9 vectors (Klein et al., 2008; Grames et al., 2018). However, this may also increase the non-specific transfer to glial cells as well as anterograde transduction (Royo et al., 2008; Foust et al., 2009; Rothermel et al., 2013). Therefore, further optimization of all the conditions including promoter specificity and viral efficiency in the Cre-targeted system would be needed to improve upon the results that we have obtained.

Although P301L tau and similar mutants have been widely used to study tau pathology in animal models, current transgenic mouse models take 4 months of age or even longer to develop motor dysfunctions (Lewis et al., 2000; Maeda et al., 2016). Our model is more robust in development of motor deficits over a short time-course (6-week period), presumably due to its specific targeting of dopaminergic neurons in the SN region, the central area of motor coordination (Klein et al., 2005). This is supported by abnormal performance of Tau-injected mice in the rotarod and balance beam tests (Fig. 2A and B), which reflect the motor coordination and balance (Karl et al., 2003), whereas they have normal muscle strength and locomotor activity as determined in forelimb grip and open field tests (Fig. 2D and E). In addition, significant motor deficit caused by the unilateral injection of mutant tau suggests a successful lesion of the dopaminergic system in mouse brain. We assumed that there was an incomplete compensation of dopamine transmission by the contralateral side. Unilateral injection of other pathogenic proteins (e.g., α-synuclein) into the SN was also reported to disrupt the dopaminergic system and cause significant motor deficits (Albert et al., 2019). Given the unilateral design in our mouse model, future study on the assessment of the turning behavior is warranted to evaluate the inter-hemispheric imbalance in dopaminergic transmission, which can be correlated with the extent of the lesion.

Furthermore, significant decrease of TH+ cells in the SN region was observed only in the Tau-injected side (Fig. 3A and C), suggesting a potential degeneration of TH+ cells probably resulting from tau expression. This was supported by the observation of Iba1+ HT7+ but not GFAP+ HT7+ cells in Tau-injected side but not in contralateral side. This is likely due to the engulfment of Tau+ degenerative neurons by microglia. Previous studies reported a selective loss of TH+ cells in the SN due to AAV infection or GFP expression (Albert et al., 2017). There was however no difference in the number of TH+ cells in ipsilateral and contralateral side of the GFP-injected mice in this study (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that AAV2/6 pseudotyped virus or GFP expression has no significant toxic effects on the injected side in our mouse model. We speculated that this toxicity might be mitigated due to the lower titer of AAV (approximately 1 × 1012 genome copy numbers per injection) used in our study. The potential detrimental effects of the AAV as well as the control transgene expression still need to be considered, as Cre-dependent AAV vectors expressing non-coding RNA could be better controls (Albert et al., 2019). In our study, the total number of GFP+ cells in GFP-injected side and the total number of HT7+ cells in Tau-injected side was comparable (Fig. 3D), revealing a similar transduction efficiency for both groups. However, the percentage of HT7+ TH+ cells in total HT7+ cells (10.26 ± 2.54%) was significantly lower than the percentage of GFP+ TH+ cells in total GFP+ cells (34.08 ± 4.00%) (Fig. 3E). These results are consistent with previous studies, suggesting that tau gene transfer might cause the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the SN region, therefore leading to the loss of TH marker (Klein et al., 2005, 2008). In addition, immunostaining by PHF1 and AT8 antibodies revealed an elevated phosphorylated form of tau in the SN. This is important because accumulative evidence reveals that highly phosphorylated tau, particularly AT8 positive tau, could lead to fibrillary deposits which are a key pathological feature of tauopathies (Santacruz et al., 2005; Berger et al., 2007; Noble et al., 2013). These cells were not positive for Thioflavin-S (data not shown), suggesting that these are not of filamentous tau accumulation. There was also no transgene expression observed in other brain regions such as the striatum after GFP/P301L tau gene transfer in SN, demonstrating no GFP/tau spread within 10WPI in our mouse model.

Overall, here we report the successful expression of P301L mutant tau in the dopaminergic neurons of the SN region by combining TH promoter Cre-driver mice with iAAV, which develops motor deficits in 6 WPI and loss of dopaminergic neurons in 10 WPI. This cell and region-specific tau expression mouse model can serve as an alternative tauopathy mouse model for PSP, CBD, and FTD with Parkinsonism (Wang and Mandelkow, 2016), and will be helpful for in vivo assessment of pathobiology and therapeutic targets for these tauopathies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Mr. Samuel Hersh and the members of Laboratory of Molecular NeuroTherapeutics for helpful suggestions and manuscript editing, and Dr. Angela Ho (Boston University) for providing Cre and ΔCre plasmids.

FUNDING

This work is funded in part by CurePSP Foundation (TI), BrightFocus Foundation (A2016551S) (TI), Coins for Alzheimer Research Trust (TI), Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (TI), NIH R01AG054672 (TI), RF1AG054199 (TI), 1R56AG057469 (TI), 5T32GM008541 (SH).

Abbreviations:

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CBD

corticobasal degeneration

- FTD

frontotemporal dementia

- PSP

progressive supranuclear palsy

- SN

substantia nigra

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SNr

substantia nigra pars reticulate

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- WPI

weeks post-injection

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTEREST

We declare no conflict of interest in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Albert K, Voutilainen MH, Domanskyi A, Airavaara M (2017) AAV vector-mediated gene delivery to substantia nigra dopamine neurons: implications for gene therapy and disease models. Genes Basel:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert K, Voutilainen MH, Domanskyi A, Piepponen TP, Ahola S, Tuominen RK, Richie C, Harvey BK, et al. (2019) Downregulation of tyrosine hydroxylase phenotype after AAV injection above substantia nigra: caution in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res 97:346–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F, Josephs KA (2018) Corticobasal degeneration: key emerging issues. J Neurol 265:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai H, Ikezu S, Woodbury ME, Yonemoto GM, Cui L, Ikezu T (2014) Accelerated neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in transgenic mice expressing P301L tau mutant and tau-tubulin kinase 1. Am J Pathol 184:808–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy D, Aponte Y, Su HH, Sternson SM (2008) A FLEX switch targets Channelrhodopsin-2 to multiple cell types for imaging and long-range circuit mapping. J Neurosci 28:7025–7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee K, Wang M, Cai E, Fujiwara N, Baker H, Cave JW (2014) Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase transcription by hnRNP K and DNA secondary structure. Nat Commun 5:5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Z, Roder H, Hanna A, Carlson A, Rangachari V, Yue M, Wszolek Z, Ashe K, et al. (2007) Accumulation of pathological tau species and memory loss in a conditional model of tauopathy. J Neurosci 27:3650–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer AL, Yu JT, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Lang AE, Hoglinger GU (2017) Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: new diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol 16:552–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Lee VM, Hatanpaa KJ, White 3rd CL, Schneider JA, et al. (2007) Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 114:5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J, Gendron TF, Prudencio M, Sasaguri H, Zhang YJ, Castanedes-Casey M, Lee CW, Jansen-West K, et al. (2015) Neurodegeneration. C9ORF72 repeat expansions in mice cause TDP-43 pathology, neuronal loss, and behavioral deficits. Science 348:1151–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G, Chinnathambi S, Lee JJ, Dombroski BA, Baker MC, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Lee SE, Klein E, et al. (2012) Evidence for a role of the rare p. A152T variant in MAPT in increasing the risk for FTD-spectrum and Alzheimer’s diseases. Hum Mol Genet 21:3500–3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Ahmed Z, Algom AA, Tsuboi Y, Josephs KA (2010) Neuropathology of variants of progressive supranuclear palsy. Curr Opin Neurol 23:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S, Jankovic J, Hallett M (2011) Principles and practice of movement disorders. Edinburgh; New York: Elsevier/Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK (2009) Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol 27:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, Johnson KA, Dickerson BC, Goedert M (2015) Invited review: Frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: a chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41:24–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grames MS, Dayton RD, Jackson KL, Richard AD, Lu X, Klein RL (2018) Cre-dependent AAV vectors for highly targeted expression of disease-related proteins and neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra. FASEB J 32:4420–4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, Wszolek Z, Reed L, Miller BI, Geschwind DH, Bird TD, et al. (1998) Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science 282:1914–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illiano P, Bass CE, Fichera L, Mus L, Budygin EA, Sotnikova TD, Leo D , Espinoza S, et al. (2017) Recombinant Adeno-associated virus-mediated rescue of function in a mouse model of dopamine transporter deficiency syndrome. Sci Rep 7:46280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isingrini E, Guinaudie C, Perret L C, Rainer Q, Moquin L, Gratton A, Giros B (2017) Genetic elimination of dopamine vesicular stocks in the nigrostriatal pathway replicates Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms without neuronal degeneration in adult mice. Sci Rep 7:12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski T, Dewachter I, Lechat B, Croes S, Termont A, Demedts D, Borghgraef P, Devijver H, et al. (2009) AAV-tau mediates pyramidal neurodegeneration by cell-cycle re-entry without neurofibrillary tangle formation in wild-type mice. PLoS One 4 e7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl T, Pabst R, von Horsten S (2003) Behavioral phenotyping of mice in pharmacological and toxicological research. Exp Toxicol Pathol 55:69 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppagounder SS, Xiong Y, Lee Y, Lawless MC, Kim D, Nordquist E, Martin I, Ge P, et al. (2016) LRRK2 G2019S transgenic mice display increased susceptibility to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-mediated neurotoxicity. J Chem Neuroanat 76:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khlistunova I, Biernat J, Wang Y, Pickhardt M, von Bergen M, Gazova Z, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM (2006) Inducible expression of Tau repeat domain in cell models of tauopathy: aggregation is toxic to cells but can be reversed by inhibitor drugs. J Biol Chem 281:1205–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Dayton RD, Lin WL, Dickson DW (2005) Tau gene transfer, but not alpha-synuclein, induces both progressive dopamine neuron degeneration and rotational behavior in the rat. Neurobiol Dis 20:64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Dayton RD, Tatom JB, Diaczynsky CG, Salvatore MF (2008) Tau expression levels from various adeno-associated virus vector serotypes produce graded neurodegenerative disease states. Eur J Neurosci 27:1615–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri N, Carlomagno Y, Baker M, Liesinger AM, Caselli RJ, Wszolek ZK, Petrucelli L, Boeve BF, et al. (2014) Novel mutation in MAPT exon 13 (p. N410H) causes corticobasal degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 127:271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs GG (2015) Invited review: neuropathology of tauopathies: principles and practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41:3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, Van Slegtenhorst M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Paul Murphy M, et al. (2000) Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet 25:402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luong TN, Carlisle HJ, Southwell A, Patterson PH (2011) Assessment of motor balance and coordination in mice using the balance beam. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Djukic B, Taneja P, Yu GQ, Lo I, Davis A, Craft R, Guo W, et al. (2016) Expression of A152T human tau causes age-dependent neuronal dysfunction and loss in transgenic mice. EMBO Rep 17:530–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble W, Hanger DP, Miller CC, Lovestone S (2013) The importance of tau phosphorylation for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurol 4:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland AS, Kareva T, Kholodilov N, Burke RE (2017) A quantitative evaluation of a 2.5-kb rat tyrosine hydroxylase promoter to target expression in ventral mesencephalic dopamine neurons in vivo. Neuroscience 346:126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel M, Brunert D, Zabawa C, Diaz-Quesada M, Wachowiak M (2013) Transgene expression in target-defined neuron populations mediated by retrograde infection with adeno-associated viral vectors. J Neurosci 33:15195–15206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo NC, Vandenberghe LH, Ma JY, Hauspurg A, Yu L, Maronski M, Johnston J, Dichter MA, et al. (2008) Specific AAV serotypes stably transduce primary hippocampal and cortical cultures with high efficiency and low toxicity. Brain Res 1190:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, Paulson J, Kotilinek L, Ingelsson M, Guimaraes A, DeTure M, et al. (2005) Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science 309:476–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitt JM, Jang SS, Mu W, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2005) Bcl-x is required for proper development of the mouse substantia nigra. J Neurosci 25:6721–6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, de Strooper B, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, Van der Flier WM (2016) Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 388:505–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber GD, Stamatakis AM, Kantak PA (2015) Considerations when using cre-driver rodent lines for studying ventral tegmental area circuitry. Neuron 85:439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mandelkow E (2016) Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 17:5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lees AJ (2009) Progressive supranuclear palsy: clinicopathological concepts and diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol 8:270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]