Abstract

Background

Chest pain center (CPC) accreditation plays an important role in the management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). However, no evidence shows whether the outcomes of AMI patients are improved with CPC accreditation in China.

Methods and Results

This retrospective analysis is based on a predesigned nationwide registry, CCC‐ACS (Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China‐Acute Coronary Syndrome). The primary outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including all‐cause death, reinfarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and heart failure. A total of 15 344 AMI patients, from 40 CPC‐accredited hospitals, were enrolled, including 7544 admitted before and 7800 after accreditation. In propensity score matching, 6700 patients in each group were matched. The incidence of 7‐day MACE (6.7% versus 8.0%; P=0.003) and all‐cause death (1.1% versus 1.6%; P=0.021) was lower after accreditation. In multivariate adjusted mixed‐effects Cox proportional hazards models, CPC accreditation was associated with significantly decreased risk of MACE (hazard ratio: 0.78; 95% CI, 0.68–0.91) and all‐cause death (hazard ratio: 0.71; 95% CI, 0.51–0.99). The risk of MACE and all‐cause death both followed a reverse J‐shaped trend: the risk of MACE and all‐cause death decreased gradually after achieving CPC accreditation, with minimal risk occurring in the first year, but increased in the second year and after.

Conclusions

Based on a large‐scale national registry data set, CPC accreditation was associated with better in‐hospital outcomes for AMI patients. However, the benefits seemed to attenuate over time, and reaccreditation may be essential for maintaining AMI care quality and outcomes.

Keywords: accreditation, acute myocardial infarction, chest pain center, China, in‐hospital outcomes

Subject Categories: Quality and Outcomes, Coronary Artery Disease

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This is the first study focus on the association of chest pain center accreditation with improved in‐hospital major adverse cardiovascular events of acute myocardial infarction patients in China based on a large‐scale national registry covering 15 344 patients from 40 hospitals.

What are the Clinical Implications?

This study demonstrated and confirmed the importance and effectiveness of chest pain center development and accreditation in China.

Hazards for the risk of outcomes during the in‐hospital period as a function of the duration of accreditation followed a reverse J‐shaped trend, with the maximum associated effectiveness occurring up until the first year after accreditation, supporting the rationale of the recently established CPC reaccreditation project to ensure a long‐lasting effect after initial CPC accreditation.

Introduction

Since 1981, when the concept of the chest pain center (CPC) was introduced, studies have shown that CPC is associated with improving timing of chest pain diagnosis, reperfusion time of ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and reduced readmissions and costs.1, 2, 3, 4 Accreditation by the Society of Chest Pain Centers (now known as the American College of Cardiology [ACC] accreditation committee) has further standardized CPCs in the United States, and the ACC accreditation committee has promoted international accreditation standards since 2010.5, 6, 7 Several countries have also established their national CPC accreditation projects, such as the Chest Pain Unit Certification Working Group issued by the German Society of Cardiology.8, 9, 10

The incidence and mortality of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are increasing in China, and the in‐hospital mortality of STEMI patients has not improved over the past decade.11, 12, 13 The development of CPCs in China was initiated in 2010, and the headquarters of China Chest Pain Centers, which oversees CPC accreditation, was officially established in July 2016 to coordinate social resources and promote the rapid development of CPCs.14, 15 To date, evidence has not shown whether the outcomes of AMI patients are improved by CPC accreditation in China. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether patients admitted for AMI after CPC accreditation had better in‐hospital outcomes than those admitted before accreditation and to further study the temporal associations of the accreditation process on AMI quality improvement.

Methods

For the concern about intellectual property and patient privacy, the data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Study Design

The CCC‐ACS (Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China–Acute Coronary Syndrome) project is a nationwide registry and quality improvement study with an ongoing database focusing on quality of acute coronary syndrome care. Details of the study design and methodology of the CCC‐ACS project have been described elsewhere.16 A standard procedure was used during data collecting from the patients’ medical records, and third‐party research associates performed regular quality audits to ensure the accuracy and completeness of research data. Institutional review board approval was granted for this research by the ethics committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, and no informed consent was required.

Study Population

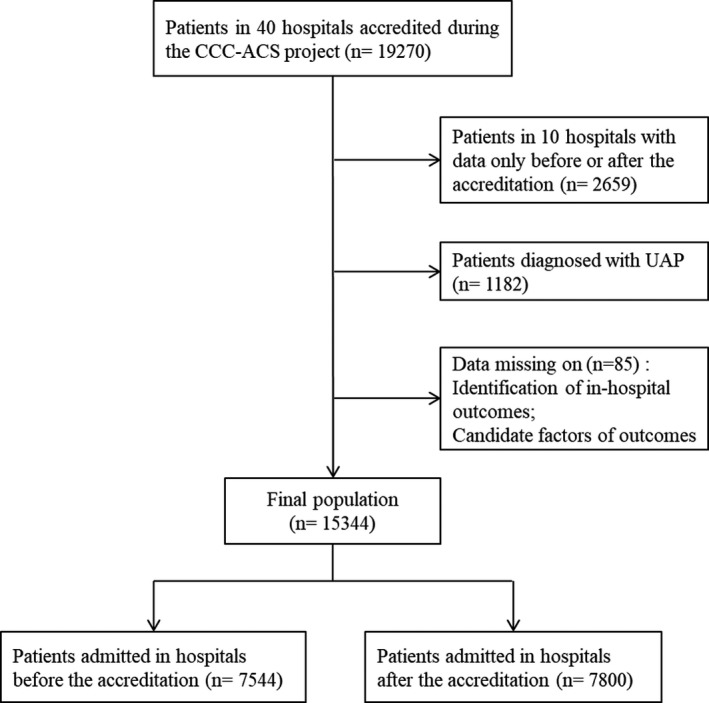

From November 1, 2014, to June 30, 2017, a total of 63 641 patients diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome from 150 hospitals were registered in the database, among which 19 270 patients from 40 accredited hospitals during this period were included in this study. We excluded 2659 patients who were admitted to 10 hospitals with data only before or after accreditation and 1182 patients diagnosed with unstable angina pectoris. In addition, 85 patients with missing data about key variables for the identification of in‐hospital outcomes and candidate factors were excluded. Finally, 15 344 patients were included in the final analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection of the study population. CCC‐ACS indicates Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China‐Acute Coronary Syndrome; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

In‐Hospital Outcomes

In this study, the primary outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including all‐cause death, reinfarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and heart failure during hospitalization. The secondary outcome was in‐hospital all‐cause death. Only those incidents that occurred within 7 days of admission were taken into account for the analysis because the main effect of the CPC was reflected a short time after the first medical contact; there will be more censored data because of hospital discharge.

Statistical Analysis

Hospital information, demographic characteristics, medical history, clinical procedures, and 7‐day in‐hospital outcomes of the participants were compared by hospital status of accreditation (before and after) when each patient was admitted. Continuous variables were shown as mean±SD. Categorical variables were presented as the number (percentage). Differences in various characteristics among the groups were compared using the Student t test and χ2 test.

The differences of 7‐day in‐hospital outcomes between the 2 groups were compared in a propensity score–matched population to minimize selection bias from the real world. Patients admitted to hospitals before accreditation were matched at a 1:1 ratio with randomly selected patients admitted to hospitals after accreditation, on the basis of nearest neighbor in terms of Mahalanobis distance with a caliper of 0.02. Propensity score was estimated with a logistic regression model with the variables of age; sex; hospital location (first‐line municipality, provincial capital, or prefecture‐level city); first medical contact site (no or yes); department arrived (emergency and catheter lab, or outpatient and others); comorbidities including smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia; heart failure history; renal failure history; previous myocardial infarction (MI); previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting; type of MI; Killip classes; preadmission use of aspirin; preadmission use of P2Y12 receptor inhibitors; and preadmission use of statins.

The incidence of 7‐day in‐hospital outcomes by hospital status of accreditation in the whole study population and in the propensity score–matched subset were compared. Because some variables were not comparable between the 2 groups even after propensity score matching, we used mixed‐effects Cox proportional hazards models containing Gaussian random effects, also known as frailty models, to compare the risk by adjusting other confounders in the logistic regression model, considering that this data set contained hospital‐level information and the data structure was hierarchical.

Subgroup analyses of 7‐day in‐hospital outcomes were then performed according to important characteristics, including age (<65 or ≥65 years), sex (male or female), city type (provincial capital or prefecture‐level city), first medical contact site (no or yes), department arrived (emergency and catheter lab, or outpatient and others), type of MI (STEMI or non‐STEMI), Killip class I (no or yes), previous MI (no or yes), and previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting (no or yes).

Considering the quality improvement effect of the CCC‐ACS project itself along with time, we performed sensitivity analyses in patients admitted to hospitals without accreditations during the project and those contemporarily admitted in hospitals after accreditation. Propensity score was also estimated with a logistic regression model with all of the listed variables included plus the admission date. Cox proportional hazards models were then used to compare the risk of 7‐day in‐hospital outcomes.

A 2‐tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. R software (http://www.R-project.org) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 15 344 patients were enrolled in this study from 40 hospitals, including 7544 admitted before the accreditation and 7800 after accreditation. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared with patients admitted to hospitals when not accredited, those admitted after accreditation were mainly from hospitals in cities of provincial capitals, had the hospital as the first medical facility, and arrived in the emergency department and catheter lab. The postaccreditation group had more patients diagnosed with STEMI and had a higher proportion of patients with Killip class I. Comparing comorbidities, patients in the postaccreditation group were less likely to have hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure history, and previous MI but more likely to have previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting. In addition, there were fewer patients to be treated with statins in the postaccreditation group regarding preadmission medications.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| Variable | Unmatched | Propensity Score Matched | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Accreditation | After Accreditation | P Value | Before Accreditation | After Accreditation | P Value | |

| n | 7544 | 7800 | 6700 | 6700 | ||

| Age, y | 62.48 (12.61) | 62.52 (12.52) | 0.838 | 62.36 (12.62) | 62.42 (12.67) | 0.782 |

| Female sex | 1796 (23.8) | 1808 (23.2) | 0.369 | 1564 (23.3) | 1566 (23.4) | 0.984 |

| Hospital location: provincial capital | 4554 (60.4) | 5122 (65.7) | <0.001 | 4240 (63.3) | 4301 (64.2) | 0.281 |

| First medical facility: hospital | 3712 (49.2) | 4124 (52.9) | <0.001 | 3367 (50.3) | 3366 (50.2) | 1.000 |

| Department: Emergency/catheter lab | 5278 (70.0) | 6046 (77.5) | <0.001 | 5025 (75.0) | 4995 (74.6) | 0.564 |

| Type of MI | ||||||

| STEMI | 5296 (70.2) | 5659 (72.6) | 0.001 | 4824 (72.0) | 4831 (72.1) | 0.908 |

| Killip class | ||||||

| I | 5298 (70.2) | 5797 (74.3) | <0.001 | 4835 (72.2) | 4879 (72.8) | 0.651 |

| II to III | 1966 (26.1) | 1735 (22.2) | 1624 (24.2) | 1593 (23.8) | ||

| IV | 280 (3.7) | 268 (3.4) | 241 (3.6) | 228 (3.4) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Current smoking | 3577 (47.4) | 3760 (48.2) | 0.335 | 3213 (48.0) | 3198 (47.7) | 0.809 |

| Hypertension | 4052 (53.7) | 3992 (51.2) | 0.002 | 3534 (52.7) | 3389 (50.6) | 0.013 |

| Dyslipidemia | 543 (7.2) | 358 (4.6) | <0.001 | 344 (5.1) | 352 (5.3) | 0.785 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1694 (22.5) | 1733 (22.2) | 0.739 | 1477 (22.0) | 1500 (22.4) | 0.648 |

| Heart failure history | 120 (1.6) | 71 (0.9) | <0.001 | 65 (1.0) | 69 (1.0) | 0.795 |

| Renal failure history | 84 (1.1) | 85 (1.1) | 0.949 | 74 (1.1) | 70 (1.0) | 0.802 |

| Previous MI | 575 (7.6) | 453 (5.8) | <0.001 | 395 (5.9) | 412 (6.1) | 0.561 |

| Previous PCI or CABG | 446 (5.9) | 519 (6.7) | 0.063 | 391 (5.8) | 412 (6.1) | 0.467 |

| Preadmission medication | ||||||

| Aspirin | 1288 (17.1) | 1259 (16.1) | 0.126 | 1081 (16.1) | 1104 (16.5) | 0.607 |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitors | 935 (12.4) | 929 (11.9) | 0.372 | 794 (11.9) | 820 (12.2) | 0.507 |

| Statins | 908 (12.0) | 815 (10.4) | 0.002 | 714 (10.7) | 738 (11.0) | 0.523 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or n (%). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

After propensity score matching, postmatching absolute standardized differences were <10% for all covariates. The mirrored histograms before and after matching are shown in Figure S1 to present the propensity score distribution status. A total of 6700 patients in each group were matched. The characteristics of the 2 groups were recompared. In the propensity score–matched population, there were no significant differences of baseline characteristics between the 2 groups except for hypertension comorbidity (Table 1).

Seven‐Day In‐Hospital Outcomes

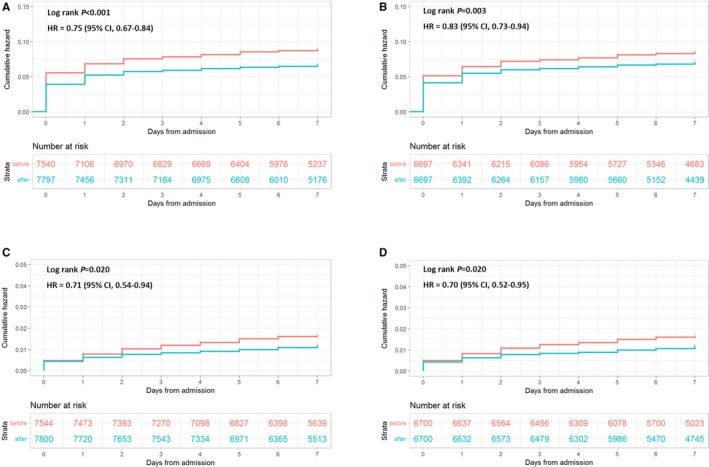

In‐hospital outcomes within 7 days of admission were compared according to accreditation status (Table 2). In the whole study population, the incidence of MACE was significantly lower in patients admitted after accreditation compared with those admitted before accreditation (6.4% versus 8.4%; P<0.001), mainly due to heart failure. The incidence of all‐cause death was also significantly lower after versus before accreditation (1.1% versus 1.6%; P=0.016). Cumulative hazards of MACE and all‐cause death were also lower in the postaccreditation group compared with the preaccreditation group (log rank P<0.001 and P=0.020, respectively; Figure 2A and 2C).

Table 2.

In‐Hospital Outcomes Within 7 Days After Hospitalizationa

| Variable | Unmatched | Propensity Score Matched | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Accreditation | After Accreditation | P Value | Before Accreditation | After Accreditation | P Value | |

| n | 7544 | 7800 | 6700 | 6700 | ||

| MACE, n (%) | 636 (8.4) | 498 (6.4) | <0.001 | 539 (8.0) | 448 (6.7) | 0.003 |

| All‐cause death, n (%) | 120 (1.6) | 88 (1.1) | 0.016 | 107 (1.6) | 75 (1.1) | 0.021 |

| Cardiac death, n (%) | 114 (1.5) | 85 (1.1) | 0.025 | 101 (1.5) | 72 (1.1) | 0.032 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 18 (0.2) | 11 (0.1) | 0.228 | 14 (0.2) | 10 (0.1) | 0.540 |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) | 10 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 0.579 | 9 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 0.802 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 12 (0.2) | 8 (0.1) | 0.456 | 11 (0.2) | 7 (0.1) | 0.479 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 547 (7.3) | 419 (5.4) | <0.001 | 459 (6.9) | 378 (5.6) | 0.004 |

Data are expressed as n (%). MACE indicates major adverse cardiovascular events.

Patients may have had >1 outcome in each category but were counted only once for overall events.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Kaplan–Meier curve estimates of outcomes within 7 days after hospitalization. Data for MACE in the whole study population (A) and the propensity score–matched population (B). Data for all‐cause death in the whole study population (C) and the propensity score‐matched population (D). HR indicates hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

After propensity score matching, the incidence of 7‐day in‐hospital MACE (6.7% versus 8.0%; P=0.003) and all‐cause death (1.1% versus 1.6%; P=0.021) was still lower in the postaccreditation group (log rank P=0.003 and P=0.020, respectively; Table 2, Figure 2B and 2D).

In mixed‐effects Cox proportional hazards models, CPC accreditation was associated with statistically significantly decreased risk of MACE (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.78; 95% CI, 0.68–0.91; P=0.001) and all‐cause death (HR: 0.71; 95% CI, 0.51–0.99; P=0.042) after multivariate analysis adjusted for possible confounders (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes Within 7 Days After Hospitalization Associated With Accreditation: Unadjusted and Multivariate Adjusted Analyses With and Without Propensity Score Matching

| Variable | Unmatched | Propensity Score Matched | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Accreditation | After Accreditation | Before Accreditation | After Accreditation | |

| MACE | ||||

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.79 (0.68–0.9) | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.74–0.98) |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.029 | ||

| Age‐ and sex‐adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) | 1.00 | 0.81 (0.7–0.94) |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.006 | ||

| Multivariate adjusted HR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 0.77 (0.67–0.88) | 1.00 | 0.78 (0.68–0.91) |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| All‐cause death | ||||

| Crude HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.67 (0.49–0.91) | 1.00 | 0.67 (0.48–0.93) |

| P value | 0.011 | 0.017 | ||

| Age‐ and sex‐adjusted HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.64 (0.47–0.88) | 1.00 | 0.64 (0.46–0.89) |

| P value | 0.005 | 0.009 | ||

| Multivariate‐adjusted HR (95% CI)a | 1.00 | 0.69 (0.5–0.95) | 1.00 | 0.71 (0.51–0.99) |

| P value | 0.022 | 0.042 | ||

HR indicates hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted for age, sex, the level of the city where the hospital is located, first medical contact site or not, comorbidities including smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, heart failure history, renal failure history, previous MI, previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting, type of MI, Killip classes, preadmission use of aspirin, preadmission use of P2Y12 receptor inhibitors, and preadmission use of statins.

Hazards for the risk of outcomes during the in‐hospital period by the duration of accreditation in the propensity score–matched population are presented in Figure 3. The risk of MACE and all‐cause death for those patients admitted after the accreditation both follow a reverse J‐shaped trend: the risk of both MACE and all‐cause death decreases gradually with CPC accreditation, with the minimal risk occurring in patients admitted from 6 months to the first year after accreditation, and then risk increases in the second year and after.

Figure 3.

Hazard for the risk of outcomes within 7 days after hospitalization by the duration of accreditation. Data for MACE in the whole study population (A) and the propensity score–matched population (B). Data for all‐cause death in the whole study population (C) and the propensity score–matched population (D). MACE indicates major adverse cardiovascular events.

Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses for MACE and all‐cause death based on baseline information were performed in the propensity score–matched population (Figures S2 and S3). The main results were not significantly changed in most subgroups. No interactions were found in most subgroups except for MACE risk by the type of MI (P=0.002 for interaction) and the disease history of previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting (P=0.049 for interaction); the associated risk of MACE was decreased more significantly after CPC accreditation in patients diagnosed with STEMI (HR: 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58–0.84) compared with those diagnosed with non‐STEMI (HR: 0.97; 95% CI, 0.75–1.26).

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses included 36 911 patients admitted to hospitals without accreditations during the project and 8858 patients contemporarily admitted in hospitals after accreditation (Figure S4). After propensity score matching at a 1:1 ratio, postmatching absolute standardized differences were <10% for all covariates except for admission date. The mirrored histograms are shown in Figure S5 to present the propensity score distribution status.

Baseline characteristics between no accreditation and postaccreditation groups before propensity score matching were not significantly different from the main results except those regarding hospital location, type of MI, and history of diabetes mellitus (Table S1). The results for the risk of in‐hospital outcomes within 7 days after admission did not significantly change except for the comparison of all‐cause death, with a P value not significantly different (Tables S2 and S3; Figure S6).

Discussion

Our study found that AMI patients admitted to hospitals with CPC accreditation had better in‐hospital outcomes than those admitted to hospitals without accreditation, based on a large‐scale national registry data set, even after propensity score matching and using Cox proportional hazards models. To our knowledge, this study is the first to focus on this issue in China. This is especially important because a previous study found no improvement of outcome for STEMI patients from 2001 to 2011.11 The results of this study confirm the importance and effectiveness of CPC development and accreditation for AMI patients in China.

The most compelling reason for hospitals and programs to obtain accreditations is better patient outcomes, but prior studies focusing on the impact of accreditation were inconclusive. A recent study including >4 million patients aged ≥65 years showed no patient mortality benefit for hospitals with a Joint Commission certification compared with those accredited by another independent accrediting organization.17 Another recent analysis showed that there might be differences in treatment and mortality for stroke patients according to which organization provided certification.18 However, regarding AMI patients, previous studies have shown that CPC accreditation was associated with better performance on core measurements,19 which is the fundamental goal for CPC accreditation.20, 21, 22, 23 These findings suggested that the improvements in care processes with CPC accreditation are further associated with improved short‐term outcomes for AMI patients.

Our study found that CPC accreditation was associated with statistically significant risk reduction of MACE and all‐cause death after adjustment. Although the main contributor to MACE improvement was heart failure, all‐cause mortality was also significantly improved with CPC accreditation, even in Cox proportional hazards models, which means the conclusion was solid. Although the history of CPC accreditation in China is relatively short, this study suggested that there were favorable associations with clinical outcomes. Further implementation and optimization of accreditation standards, focused especially on core measurements for care management of AMI patients, may be warranted.

In 2010, the China Expert Consensus on the Construction of Chest Pain Centers was published and played a crucial role in promoting the development of CPCs at that time.15 The first CPC in China with the regional collaborative network as its core concept was established in March 2011 in Guangzhou. With the scope of collaboration with resources and promoting the rapid development of CPCs, the China Cardiovascular Association and the Chinese Society of Cardiology collaboratively established the China Chest Pain Center in July 2016. After its establishment, this CPC assumed responsibility for most of the organization, management, and coordination originally undertaken by the China Chest Pain Center Accreditation Office. More details on the process, benchmarks, requirements, and so forth, according to CPC certification in China are provided in Data S1 for reference.

An important insight from this study is that the hazards for the risk of outcomes during the in‐hospital period as a function of the duration of accreditation followed a reverse J‐shaped trend, with the maximum associated effectiveness occurring up until the first year after accreditation. This finding supports the rationale of the recently established reaccreditation project, which may promote a long‐lasting effect after initial CPC accreditation and help to limit subsequent declines in associated benefits for AMI care and outcomes with CPC accreditation after the first year. In January 2018, considering continuing quality improvement, the headquarters of China CPCs formally established a reaccreditation protocol and standard that demands a 3‐year validation period for the initial CPC accreditation. The validation period for the reaccreditation of CPCs will be 5 years, and reaccreditation should be performed every 5 years.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective observational study; even using propensity score matching, we could not eliminate bias from unobserved variables. A follow‐up study with a more robust design, such as prospective cluster randomization, would be warranted. Second, the difference in outcomes was largely driven by difference in heart failure and all‐cause death, which should be taken into consideration in the interpretation of results. Third, hospitals involved in CCC‐ACS projects cannot reflect the whole picture of China's hospitals with and without CPC accreditation; furthermore, this study focuses on only AMI rather than all acute chest pain diagnoses and diseases. Last, our analysis was able to focus on only in‐hospital outcomes rather than effect of accreditation on long‐term outcome improvements, which can be further studied in the future.

Conclusions

Based on a large‐scale national registry data set, CPC accreditation was associated with better in‐hospital outcomes for AMI patients. However, because there was some attenuation in associated benefits over time, reaccreditation may be essential to maintain the quality of AMI care after initial CPC accreditation.

Sources of Funding

The CCC‐ACS (Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China‐Acute Coronary Syndrome) project is a collaborative program of the American Heart Association (AHA) and Chinese Society of Cardiology. The AHA was funded by Pfizer for the quality‐improvement initiative through an independent grant for learning and change.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Group information: hospitals for phase 1 (investigator).

Data S1. Details on the process, benchmarks, and requirements for chest pain center accreditation in China

Table S1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population in Sensitivity Analyses

Table S2. In‐Hospital Outcomes Within 7 Days After Hospitalization* in Sensitivity Analyses

Table S3. Independent Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Propensity Score–Matched Population in Sensitivity Analyses

Figure S1. Mirrored histogram before (A) and after (B) propensity score matching. The x‐axis shows the number of patients in each group. The y‐axis shows the propensity score. The red bar presents the preaccreditation group, and the blue bar shows the postaccreditation group.

Figure S2. Subgroup analyses for MACE in the propensity score–matched population. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; cath, catheter; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure S3. Subgroup analyses for all‐cause death in the propensity score–matched population. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; cath, catheter; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure S4. Flow diagram of selection of the study population in sensitivity analyses. CCC‐ACS indicates Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China‐Acute Coronary Syndrome; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Figure S5. Mirrored histogram before (A) and after (B) propensity score matching in sensitivity analyses. The x‐axis shows the number of patients in each group. The y‐axis shows the propensity score. The red bar presents the no‐accreditation group, and the blue bar shows the postaccreditation group.

Figure S6. Cumulative Kaplan–Meier curve estimates of outcomes within 7 days after hospitalization in sensitivity analyses. Data for MACE in the whole study population (A) and the propensity score–matched population (B). Data for all‐cause death in the whole study population (C) and the propensity score–matched population (D). HR indicates hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all participating hospitals for their contributions to the CCC‐ACS (Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China‐Acute Coronary Syndrome) project.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013384 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013384.)

References

- 1. Goodacre S, Nicholl J, Dixon S, Cross E, Angelini K, Arnold J, Revill S, Locker T, Capewell SJ, Quinney D, Campbell S, Morris F. Randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of a chest pain observation unit compared with routine care. BMJ. 2004;328:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Keller T, Post F, Tzikas S, Schneider A, Arnolds S, Scheiba O, Blankenberg S, Münzel T, Genth‐Zotz S. Improved outcome in acute coronary syndrome by establishing a chest pain unit. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Graff LG, Dallara J, Ross MA, Joseph AJ, Itzcovitz J, Andelman RP, Emerman C, Turbiner S, Espinosa JA, Severance H. Impact on the care of the emergency department chest pain patient from the chest pain evaluation registry (CHEPER) study. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steurer J, Held U, Schmid D, Ruckstuhl J, Bachmann LM. Clinical value of diagnostic instruments for ruling out acute coronary syndrome in patients with chest pain: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peacock WF, Kontos MC, Amsterdam E, Cannon CP, Diercks D, Garvey L, Graff L IV, Holmes D, Holmes KS, McCord J, Newby K, Roe M, Dadkhah S, Siler‐Fisher A, Ross M. Impact of Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care accreditation on quality: an ACTION Registry®‐Get With The Guidelines™ analysis. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2013;12:116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joseph AJ, Cohen AG, Bahr RD. A formal, standardized and evidence‐based approach to Chest Pain Center development and process improvement: the Society of Chest Pain Centers and Providers accreditation process. J Cardiovasc Manag. 2003;14:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bahr RD. Milestones in the development of the first chest pain center and development of the new Society of Chest Pain Centers and Providers. Md Med. 2001;Spring(Suppl):106–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breuckmann F, Burt DR, Melching K, Erbel R, Heusch G, Senges J, Garvey JL. Chest pain centers: a comparison of accreditation programs in Germany and the United States. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2015;14:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Münzel T, Post F. The development of chest pain units in Germany. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:657–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Post F, Gori T, Senges J, Giannitsis E, Katus H, Münzel T. Establishment and progress of the chest pain unit certification process in Germany and the local experiences of Mainz. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:682–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li J, Li X, Wang Q, Hu S, Wang Y, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM, Jiang L; China PEACE Collaborative Group . ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE‐Retrospective Acute Myocardial Infarction Study): a retrospective analysis of hospital data. Lancet. 2015;385:441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, Chen W, Wang L, Liu S, Li Y, Wang L, Liu Y, Yin P, Liu J, Yu S, Tan F, Barber RM, Coates MM, Dicker D, Fraser M, González‐Medina D, Hamavid H, Hao Y, Hu G, Jiang G, Kan H, Lopez AD, Phillips MR, She J, Vos T, Wan X, Xu G, Yan LL, Yu C, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Zou X, Naghavi M, Wang Y, Murray CJ, Yang G, Liang X. Cause‐specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990–2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387:251–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Recent hospitalization trends for acute myocardial infarction in Beijing. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3188–3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Huo Y. Early reperfusion strategy for acute myocardial infarction: a need for clinical implementation. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:629–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan Z, Yong H. Current status and future prospects of chest pain center accreditation in China. China Acad J Electron Publ House. 2017;9:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hao Y, Liu J, Liu J, Smith SC Jr, Huo Y, Fonarow GC, Ma C, Ge J, Taubert KA, Morgan L, Guo Y, Zhang Q, Wang W, Zhao D; CCC‐ACS Investigators . Rationale and design of the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China (CCC) project: a national effort to prompt quality enhancement for acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2016;179:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lam MB, Figueroa JF, Feyman Y, Reimold KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Association between patient outcomes and accreditation in US hospitals: observational study. BMJ. 2018;363:k4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Man S, Cox M, Patel P, Smith EE, Reeves MJ, Saver JL, Bhatt DL, Xian Y, Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC. Differences in acute ischemic stroke quality of care and outcomes by primary stroke center certification organization. Stroke. 2017;48:412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ross MA, Amsterdam E, Peacock WF, Graff L, Fesmire F, Garvey JL, Kelly S, Holmes K, Karunaratne HB, Toth M, Dadkhah S, McCord J. Chest pain center accreditation is associated with better performance of centers for medicare and medicaid services core measures for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bahr RD, Copeland C, Strong J. Chest pain centers–Part 1. Chest pain centers: past, present and future. J Cardiovasc Manag. 2002;13:19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bahr RD, Copeland C, Strong J. Chest pain centers–Part 2. The strategy of the chest pain center. J Cardiovasc Manag. 2002;13:21–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bahr RD, Copeland C, Strong J. Chest pain centers–Part 3. Evaluation in the hospital ED or chest pain center (CPC). J Cardiovasc Manag. 2002;13:23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bahr RD, Copeland C, Strong J. Chest pain centers–Part 4. Executive summary: issues with APC's and observation services. J Cardiovasc Manag. 2002;13:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Group information: hospitals for phase 1 (investigator).

Data S1. Details on the process, benchmarks, and requirements for chest pain center accreditation in China

Table S1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population in Sensitivity Analyses

Table S2. In‐Hospital Outcomes Within 7 Days After Hospitalization* in Sensitivity Analyses

Table S3. Independent Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Propensity Score–Matched Population in Sensitivity Analyses

Figure S1. Mirrored histogram before (A) and after (B) propensity score matching. The x‐axis shows the number of patients in each group. The y‐axis shows the propensity score. The red bar presents the preaccreditation group, and the blue bar shows the postaccreditation group.

Figure S2. Subgroup analyses for MACE in the propensity score–matched population. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; cath, catheter; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure S3. Subgroup analyses for all‐cause death in the propensity score–matched population. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; cath, catheter; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure S4. Flow diagram of selection of the study population in sensitivity analyses. CCC‐ACS indicates Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China‐Acute Coronary Syndrome; UAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Figure S5. Mirrored histogram before (A) and after (B) propensity score matching in sensitivity analyses. The x‐axis shows the number of patients in each group. The y‐axis shows the propensity score. The red bar presents the no‐accreditation group, and the blue bar shows the postaccreditation group.

Figure S6. Cumulative Kaplan–Meier curve estimates of outcomes within 7 days after hospitalization in sensitivity analyses. Data for MACE in the whole study population (A) and the propensity score–matched population (B). Data for all‐cause death in the whole study population (C) and the propensity score–matched population (D). HR indicates hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.