Abstract

Background

The number of incidental meningiomas has increased because of the increased availability of neuroimaging. Lack of prospective data on the natural history makes the optimal management unclear. We conducted a 5-year prospective study of incidental meningiomas to identify risk factors for tumor growth.

Methods

Sixty-four of 70 consecutive patients with incidental meningioma were included. Clinical and radiological status was obtained at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. GammaPlan and mixed linear regression modeling were utilized for volumetric analysis with primary endpoint tumor growth.

Results

None of the patients developed tumor-related symptoms during the study period, although 48 (75%) tumors increased (>15%), 13 (20.3%) remained unchanged, and 3 (4.7%) decreased (>15%) in volume. Mean time to growth was 2.2 years (range, 0.5-5.0 years).

The growth pattern was quasi-exponential in 26%, linear in 17%, sigmoidal in 35%, parabolic in 17%, and continuous reduction in 5%. There was significant correlation among growth rate, larger baseline tumor volume (P < .001), and age in years (<55 y: 0.10 cm3/y, 55-75 y: 0.24 cm3/y, and >75 y: 0.85 cm3/y).

Conclusion

The majority of meningiomas will eventually grow. However, more than 60% display a self-limiting growth pattern. Our study provides level-2 evidence that asymptomatic tumors can be safely managed utilizing serial imaging until persistent radiological and/or symptomatic growth.

Keywords: asymptomatic meningioma, incidental meningioma, natural history, prospective study, volumetric tumor growth

Meningioma is the most common benign intracranial tumor,1 most commonly affecting women and the elderly.2 Owing to an aging population and increased use of MRI, the number of patients diagnosed with incidental meningiomas has increased. Recent studies have shown that incidental meningiomas are present on brain MRI scans of 0.9% to 1.0% of the general population.3,4 Autopsy studies have shown an incidence of meningioma of about 2% to 3%. The size of tumors has also increased with advancing age,5 implying that a large number of incidental meningiomas may remain asymptomatic despite growth.

Benign meningiomas have a propensity to recur if surgical removal is incomplete.6 The gold-standard treatment of benign symptomatic meningioma is complete surgical excision of the tumor and its dural base. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) may be used for meningiomas of limited size, and this modality is often used to treat remnants or recurrent tumors. The optimal treatment of incidental meningioma is less clear. Because these tumors are asymptomatic, data on their natural history have been sparse and good evidence-based guidelines for follow-up and treatment are lacking.

There are no prospective studies comparing long-term outcome between observation and early treatment. A retrospective study comparing up-front SRS with observation concluded that despite a risk of adverse effects of 13.3%, proactive SRS may be a reasonable option.7 Another study comparing surgical resection with the natural course advocated conservative treatment to avoid surgical morbidity.8 Most neurosurgical practices opt for a conservative approach for incidental tumors. They are usually followed by repeated imaging and treated at the time of radiological and/or symptomatic progression. Nevertheless, there are many discrepancies in management strategies of incidental meningiomas. A newly published survey of the management of incidental meningioma highlights the variations in management and the need for prospective studies to establish guidelines.9

Several retrospective studies have been conducted,7,8,10–26 often using nonstandardized definitions for tumor growth. Unsurprisingly, the reported growth rates vary within a wide range: from 11.4% to 74.2% of tumors, of which 0% to 55.8% became symptomatic. The majority of studies conclude that close observation is safe, although some advocate surgery for younger patients,10 patients age 60 and younger,15 or patients younger than 70 years.14 One study recommended Gamma Knife surgery (GKS; Elekta) for cavernous sinus location.20 The conclusions of 4 reviews based on these studies are as follows: 1) neurosurgical consultation is recommended for all meningiomas as some even small tumors must be treated because of risk of symptoms,27 2) conservative treatment is recommended, especially for tumors smaller than 2 cm,28 3) initial close follow-up is recommended; however, further follow-up intervals can be tailored according to tumor behavior,29 and 4) volumetric growth rates may predict histological diagnosis and clinical outcome.30 Nevertheless, lack of prospective data and randomized trials still leave optimal management unclear.

We have conducted a 5-year prospective follow-up study of all incidental meningioma patients referred from a population of 1 million during a 1.5-year period to define the natural history and to identify potential risk factors for tumor growth.

Material and Methods

Study Design

We have conducted a longitudinal prospective study of patients with incidental meningioma and included a retrospective arm for comparison. Primary endpoints were radiological or symptomatic tumor progression resulting in treatment. The indication for treatment was set at a weekly multidisciplinary neuro-oncology meeting depending on tumor volume, tumor location, and patient factors. Patients treated conservatively despite growing tumors remained in the study.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Prospective Arm

During the period June 2009 until January 2011, all patients with incidental meningioma referred to the neurosurgical department at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, were assessed for inclusion in the prospective arm of the study. Incidental meningioma was defined as an asymptomatic meningioma detected unexpectedly or discovered under investigation for mild and unspecific symptoms such as headache or dizziness. These symptoms either resolved spontaneously before referral or were deemed to have other causes and could not be explained by the size and/or location of the tumor. The decision as to whether the meningioma was incidental was made at the multidisciplinary weekly held tumor board meeting. All patients were followed clinically and radiologically at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, and thereafter at 3, 4, and 5 years.

Inclusion criteria included the following:

1) meningioma diagnosed on MRI by a neuroradiologist;

2) incidental and asymptomatic lesion;

3) age 18 years or older; and

4) signed written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included the following:

1) radiological uncertainty of diagnosis;

2) prior diagnosis of primary brain tumor;

3) patient declined to participate; or

4) prior treatment for meningioma.

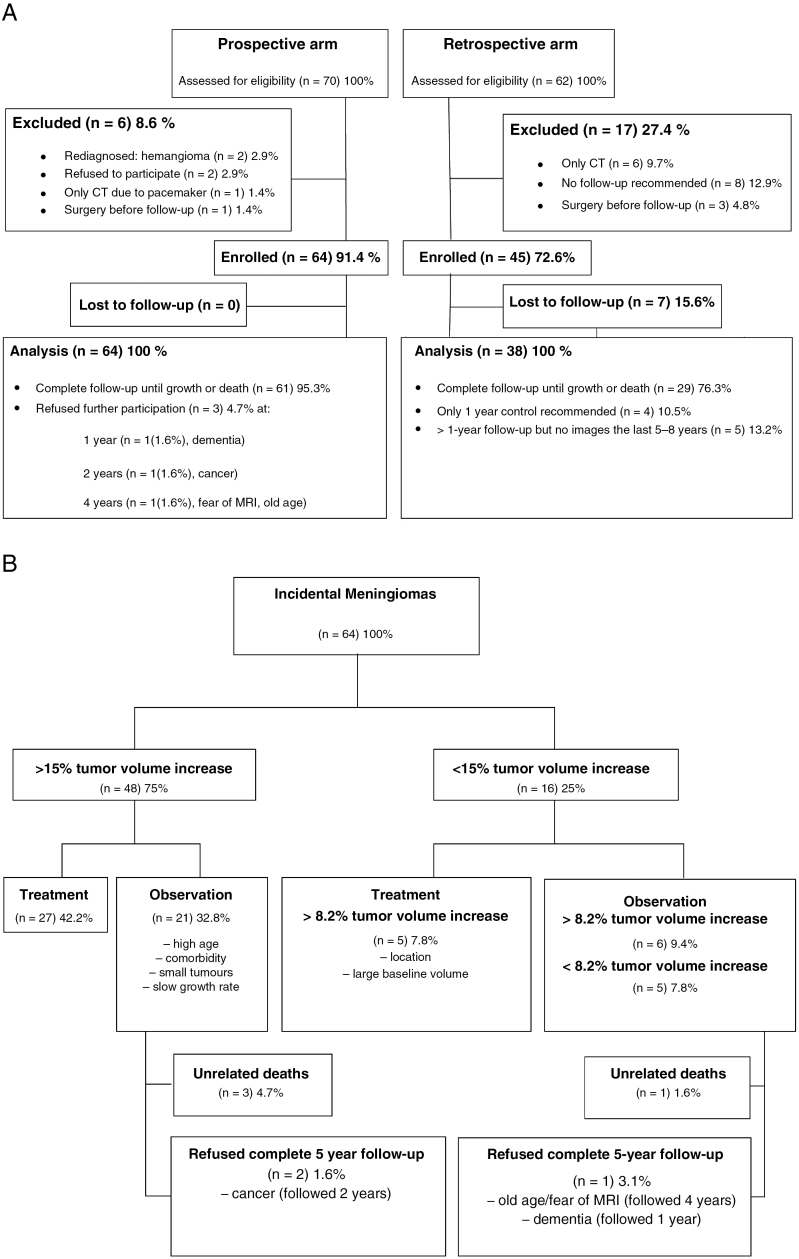

Seventy patients were assessed for eligibility; of these 64 (91.2%) were enrolled. In 2 patients the diagnoses were revised following reevaluation of MRI. One patient with a pacemaker was excluded because the CT scans were deemed unsuitable for accurate volume measurements. Two patients declined to participate, and 1 patient underwent surgery before the first follow-up (Fig. 1A). Patient and tumor characteristics of the prospective arm are presented in Table 1. The treatment algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 1B.

Fig. 1.

A, Flowchart illustrating the exclusion and enrollment of incidental meningioma patients, 70 prospective and 62 retrospective patients, referred to the Department of Neurosurgery, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. B, Treatment algorithm for the 64 enrolled prospective patients.

Table 1.

Distribution of Baseline Characteristics for 64 Patients With 66 Incidental Meningiomas Referred to the Department of Neurosurgery, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway From May 2009 Until September 2010

| Patient/Tumor Characteristics | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Tumor volume in cm3, mean (range) | 4.9 (0.03-35.2) |

| Single vs multiple meningiomas, n (%) | 63 (98.4) vs 1 (1.6) |

| Round vs irregular tumor shape, n (%) | 48 (72.7) vs 18 (27.3) |

| Presence of: n (%) | 66 (100.0) |

| Peritumoral edema | 3 (4.7) |

| Cyst | 3 (4.7) |

| Hyperostosis | 8 (12.5) |

| Calcification | 30 (45.5) |

| Involvement of falx/venous sinus | 24 (37.5) |

| MRI T2-signal hyperintensity | 28 (42.4) |

| Localization, n (%) | 64 (100.0) |

| Convexity | 16 (25.0) |

| Falx | 8 (12.5) |

| Infratentorial | 9 (14.0) |

| CP angle | 6 (9.4) |

| Clivus | 4 (6.3) |

| Other | 23 (34.8) |

| Skull base/Non–skull base | 24 (36.4)/42 (65.6) |

| Reason for first MRI, n (%) | 64 (100.0) |

| Headache | 14 (21.9) |

| Dizziness | 12 (18.8) |

| Head injury | 5 (7.8) |

| Screening other disease | 4 (6.3) |

| Syncope | 3 (4.7) |

| Sinusitis | 2 (3.1) |

| Unrelated neurological symptoms | 17 (26.6) |

| Other | 7 (10.9) |

| Height in m, mean (range) | 1.66 (1.53-1.87) |

| Weight in kg, mean (range) | 70.1 (46-108) |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean (range) | 24.8 (18-36.3) |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 64 (34-85) |

| Females, n (%) | 47 (73) |

| Prior or current use of oral contraceptives vs not | 20/47 (42.6) vs 27/47 (57.4) |

| Prior or current use of estrogen replacement therapy vs not | 14/47 (29.8) vs 33/47 (70.2) |

| No. of pregnancies, n (%) (missing value: 1 of 47) | 46 (100.0) |

| 0 | 3 (6.5) |

| 1 | 2 (4.3) |

| 2 | 13 (28.3) |

| 3 | 13 (28.3) |

| 4 | 8 (17.4) |

| 5-7 | 7 (15.2) |

| Mean (SEM) | 3.11 |

| No children, n (%) | 47 (100.0) |

| 0 | 4 (8.5) |

| 1 | 1 (2.1) |

| 2 | 15 (31.9) |

| 3 | 12 (25.5) |

| 4 | 9 (19.1) |

| 5-7 | 6 (12.8) |

| Mean (SEM) | 2.89 |

Abbreviations: CP: cerebellopontine angel; SEM: standard error of the mean.

Retrospective Arm

All patients referred to the weekly held multidisciplinary neuro-oncology meeting between January 2007 and May 2009 were reviewed. Sixty-two patients with asymptomatic meningiomas were identified, of whom 38 (61.3%) could be evaluated retrospectively for the natural history. Of the remaining 24 (38.7%) patients, 7 were lost to follow-up, no follow-up was recommended because of advanced age or low risk of growth in 8, follow-up was performed with CT scans only (n = 6), or the tumors were treated immediately (n = 3) (see flowchart in Fig. 1A). Mean age was 61 (range, 23-90 years). There were 30 women and 8 men (ratio 3.8:1). Mean baseline volume was 5.4 cm3 (range, 0.1–25.1 cm3). Follow-up ranged from 1 to 10 years, although in dissimilar intervals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of Patients With Incidental Meningiomas Increasing More Than 15% in Tumor Volume and Number of Patients Available for Volume Assessment at Baseline and During Follow-Up Time Points for the Prospective Study Arm (n = 64) and the Retrospective Study Arm (n = 38) at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, Between January 2007 and January 2011

| Follow-Up (Years)→ Study↓ |

0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective | |||||||||||||||

| Availablea | n | 64 | 64 | 52 | 43 | 38 | 30 | 27 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| (%) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (81.3 | (67.2) | (59.4) | (46.9) | (42.2) | (39.1) | (39.1) | ||||||

| Treated Ib | n | 8 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 | ||||||

| (%) | (12.5) | (10.9) | (7.8) | (9.4) | (42.2) | ||||||||||

| Treated IIc | n | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||||||

| (%) | (6.3) | (1.6) | (7.8) | ||||||||||||

| Unrelated deaths | n | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | ||||||||||

| (%) | (1.6) | (4.7) | (6.2) | ||||||||||||

| Refused | n | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |||||||||

| (%) | (1.6) | (1.6) | (1.6) | (4.7) | |||||||||||

| Retrospective | |||||||||||||||

| Availablea | n | 38 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 32 | 31 | 26 | 23 | 19 | 14 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| (%) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100) | (86.8) | (84.2) | (81.6) | (68.4) | (60.5) | (50.0) | (36.8) | (26.3) | (18.4) | (10.5) | (5.3) | |

| Treated Ib | n | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 | |||

| (%) | (5.3) | (2.6) | (2.6) | (10.5) | (2.6) | (5.3) | (5.3) | (2.6) | (2.6) | (2.6) | (42.1) | ||||

| Unrelated deaths | n | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||

| (%) | (2.6) | (2.6) | (2.6) | (7.9) | |||||||||||

| Lost to follow-up | n | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 | ||||

| (%) | (7.9) | (2.6) | (2.6) | (5.3) | (5.3) | (5.3) | (5.3) | (5.3) | (5.3) | (44.7) |

aTumors unchanged or followed despite growth.

bTumors treated because of more than 15% volume increase.

cTumors treated because of more than 8.2% volume increase.

Ethical Consideration

Approval for this study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Committee for Medical Research (REK, 2009/5821).

Clinical and Radiological Assessment at Baseline

All patients in the prospective arm were assessed by a neurosurgeon at the time of first radiological follow-up. Indication for the initial MRI examination, neurological symptoms and clinical findings, age, gender, and BMI were collected. Use of oral contraceptives, hormone-replacement therapy, and number of pregnancies and children were noted in female patients. Radiological characteristics, tumor location, multiplicity, volume, shape, MRI T2-signal intensity, peritumoral edema, calcification, cystic components, hyperostosis, and falx or venous sinus involvement were evaluated.

Clinical and Radiological Assessment at Follow-Up

Patients included in the study were followed clinically and underwent gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. At each follow-up the patient was asked about clinical symptoms. New neurological symptoms and changes in preexisting complaints were registered. GammaPlan software (Elekta) was used for the evaluation of volumetric changes in tumor volume and surrounding edema.

Primary Endpoint: Tumor Growth

Overall tumor growth was determined using 3 methods:

1) a more than 15%11,12 and more than 8.2%,13,16 respectively, increase in tumor volume, in concordance with previous studies;

2) tumor volume increase measured as cm3 per year; and

3) tumor doubling time (Td) per number of doublings per year.

Survival data and the cause of death were recorded. Progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the length of time the lesion remained unchanged (ie, ≤15% increase in volume without treatment), was recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as counts, percentages (%), means, SDs, medians, ranges, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Prognostic factors for tumor growth were analyzed using mixed linear regression modeling (MLM)31 with the 8 time points (0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months) assuming an autoregressive correlation structure of first order. In all models tumor volume, time, age, and gender were included as covariates.

Analyses of tumor volume changes (cm3 per year) were performed adding only 1 of the other potential prognostic factors at a time as covariates: tumor location, shape, MRI T2-signal intensity, presence of peritumoral edema, calcification, cysts, involvement of falx or sinus, hyperostosis, BMI, use of oral contraceptives or hormone-replacement therapy, and number of pregnancies and number of children. Interactions between each of these and time since initial MRI were tested. Variables were defined as either continuous (age, baseline tumor volume, BMI, number of pregnancies and children) or dichotomous (peritumoral edema, non–skull base location, female gender, calcification, cystic, falx or sinus involvement, hyperostosis, MRI T2-signal hyperintensity, irregular tumor form, use of oral contraceptives, and hormone-replacement therapy).

We calculated overall tumor growth using previously described formulas (ie, increase in volume by 15% or 8.2%).

Td was calculated by Td = (t2–t1) × log(2)/log(q2/q1), where t1 represents the baseline date or time of diagnosis, t2 is the last follow-up point, and q1 and q2 are volumes at baseline and last follow-up, respectively. The number of Td per year was calculated as 1/Td. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to calculate overall and PFS. Statistical significance was set at P ≤.05. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS, version 24 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Part 1—The Prospective Study Arm

Sixty-one of 64 (95.3%) patients completed the scheduled follow-up until the primary endpoint was reached.

Thirty-two patients underwent surgery or GKS and 4 (6.3%) died of unrelated causes (2 of cardiac disease, 2 of cancer). Three of the deceased patients had tumor growth but none were treated. One was deemed unfit for treatment, and 2 had small tumors and were managed with continued observation. The fourth deceased patient’s meningioma shrunk in size.

Three patients failed to complete the 5-year follow-up. One developed dementia and was followed for 1 year, during which the tumor increased 8.2% in volume. The other patient had progressive malignant disease diagnosed after inclusion and thus withdrew from the study. She was followed 2 years for a tumor that grew more than 15% in size. The third patient was followed for 4 years, during which the tumor showed a reduction in size. The patient withdrew from the study because of severe claustrophobia.

Thus, the numbers of patients available for volume assessment at baseline and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years were 64, 64, 52, 43, 38, 30, 27, and 25, respectively (Table 2).

Overall Tumor Growth Rate

Applying the 15% volume increase to define tumor growth, 48 (75.0%) tumors increased in volume, 13 (20.3%) remained unchanged, and 3 (4.7%) became smaller. Utilizing an 8.2% cut-off, 55 (85.9%) increased in volume, 6 (9.4%) remained unchanged, and 3 (4.7%) reduced. The numbers of growing tumors treated with surgery or GKS at each evaluation point are presented in Table 2.

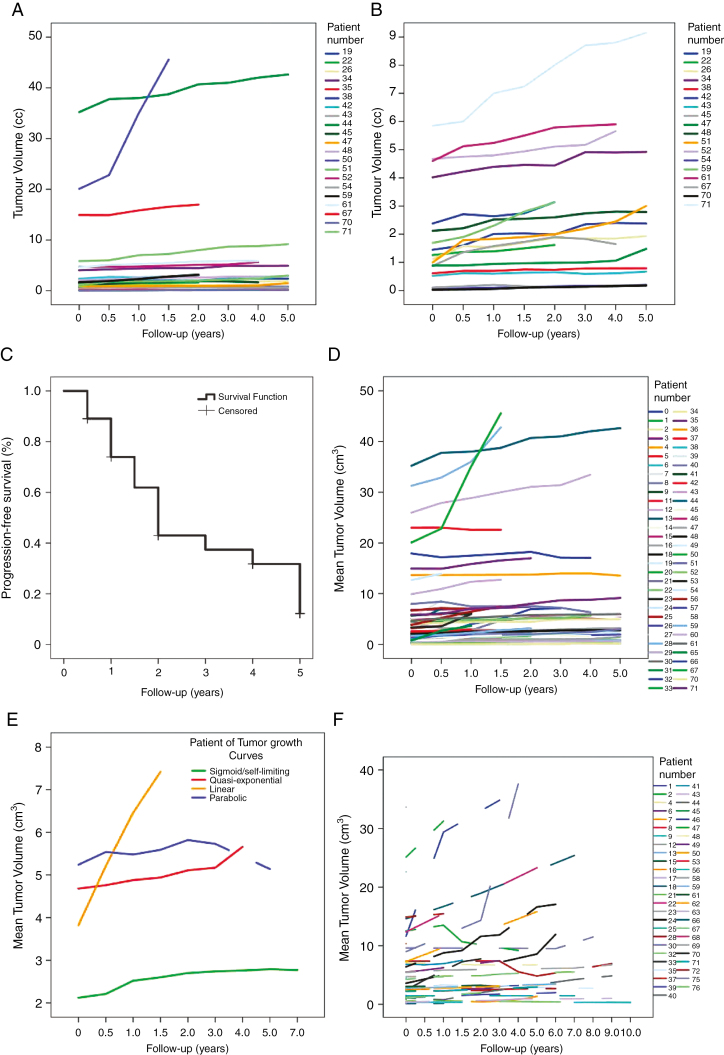

Of the 48 patients whose tumors increased more than 15% in volume, 27 underwent surgical resection or GKS. The remaining 21 were kept in the observation group because of advanced age, comorbidities, small baseline volume, or slow growth rate. Fig. 2A demonstrates the individual growth curves for these tumors. In Fig. 2B the 3 largest tumors have been excluded to separate the curves for the smaller lesions more clearly. Patients who were observed despite tumor growth were significantly older than the treated patients, 70 years vs 61 years, (P = .027).

Fig. 2.

A, Individual tumor growth curves for all 21 of 48 tumors that increased more than 15% in volume but were continued on conservative treatment because of high age, comorbidity, small tumor volume, or slow growth rate. B, Individual tumor growth curves for 18 of the 21 tumors that increased more than 15% in volume but continued on conservative treatment excluding the 3 largest tumors to better separate the individual curves for the small tumors. C, Kaplan–Meier progression-free survival curve for 64 patients with incidental meningioma followed prospectively for 5 years or until death or documented tumor volume increase of more than 15%. D, Individual tumor growth curves for all 64 prospective patients. E, The principle growth curves observed for the 64 prospective and 38 retrospective tumors included in the study: quasi-exponential, linear, sigmoid, and parabolic growth pattern. F, Individual tumor growth curves for all 38 retrospective patients.

In 16 patients tumor enlargement was less than 15%. Five of these patients had tumors that increased more than 8.2% in volume and were treated with surgery or GKS because of their anatomic location or large baseline tumor volume. The remaining 11 patients, including 6 with lesions showing at least an 8.2% increase in volume, were managed conservatively (Fig. 1B).

PFS

Utilizing the 15% tumor volume increase as definition for growth, median PFS was 2.0 years (95% CI: 1.67 to 2.33). The life tables show 89.1% PFS at 6 months, 73.9% at 1 year, 61.9% at 18 months, 43.0% at 2 years, 37.4% at 3 years, 31.8% at 4 years, and 12.2% at 5 years (Fig. 2C).

Mean Tumor Growth Rate per Year

Mean overall tumor growth rate was 0.33 cm3 per year (95% CI: 0.14 to 0.52; P < .001) when corrected for age, gender, and baseline tumor volume (Fig. 2D).

Baseline Predictors for the Growth Rate of Meningiomas

There was a significant correlation between larger baseline tumor volume and growth rate both as a continuous and a categorical variable (P < .001, Table 3).

Table 3.

Results from Mixed Linear Regression Analysesa of Volumetric Tumor Growth in cm3 and Baseline Predictors for Growth of Untreated Incidental Meningiomas in 64 Prospective Patients Followed From June 2009 to January 2011 and 38 Retrospective Patients Between January 2007 to May 2009 at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway

| Tumor Volume (cm3) (Range, 0.03-35.2) | Prospective Study (N = 64) | Retrospective Study (N = 38) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory Variables | b | 95% CI | P Value | b | 95% CI | P Value |

| Model 1b | ||||||

| Time (years) | 0.33 | (0.14, 0.52) | .001 | 0.50 | (0.15, 0.85) | .005 |

| Age (years) | 0.01 | (–0.03, 0.05) | .490 | 0.11 | (–0.03, 0.26) | .119 |

| Male (vs female) | 0.33 | (–0.74, 1.41) | .537 | 1.46 | (–6.88, 3.95) | .584 |

| Tumor volume (cm3) | 1.12 | (1.05, 1.18) | <.001 | 0.13 | (–0.01, 0.28) | .063 |

| Analyses of Interactionsc | ||||||

| Baseline Tumor Volume (cm3) | ||||||

| Time × volume | 0.06 | (0.04, 0.08) | <.001 | 0.15 | (0.10, 0.21) | <.001 |

| Time-Effect Within Volume Category | ||||||

| Volume < 4.2 cm3 | 0.23 | (–0.04, 0.49) | 0.00 | (–0.39, 0.40) | ||

| Volume 4.2–8.2 cm3 | 0.17 | (–0.31, 0.65) | 0.44 | (–0.18, 1.06) | ||

| Volume >8.2 cm3 | 1.65 | (1.08, 2.21) | 2.13 | (1.37, 2.89) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Time × age | 0.01 | (0.003, 0.09) | .011 | |||

| Time-Effect Within Age Category | ||||||

| <55 years | 0.10 | (–0.28, 0.48) | ||||

| 55-75 years | 0.24 | (–0.02, 0.49) | ||||

| >75 years | 0.86 | (0.46, 1.26) | ||||

| Hyperostosis (yes vs no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.37 | (0.12, 2.61) | .031 | |||

| Time × Hyperostosis | .100 |

Abbreviations: b, regression coefficient; P, from F-test for time adjusted for age, gender, time, and baseline tumor volume.Bold values represents significant P values.

aA first-order autoregressive correlation structure was assumed for all models.

bModel 1: Estimates from model with only the main effects of age, gender, baseline tumor volume, and time.

cAnalyses of interactions: Adding 1 variable (tumor location, shape, MRI T2-signal intensity, presence of peritumoral edema, calcification, cysts, hyperostosis, involvement of falx or sinus) at the time to the variables in model 1 and testing interaction of this with time. Results shown only for significant interactions.

Higher age was significantly associated with faster tumor growth rate measured as volume increase (cm3 per year) as a continuous and categorical variable. For patients younger than 55 years, the tumors grew at a rate of 0.10 cm3 per year (–0.28 to 0.48). For patients between 55 and 75 years, tumors grew at a rate of 0.24 cm3 per year (–0.02 to 0.49). Finally, for patients older than 75 years the tumor growth rate was 0.86 cm3 per year (0.47 to 1.26), P = .014. Notably, tumor volume at diagnosis was significantly higher for elderly patients, with mean (SD) 8.3 cm3 (10.4 cm3) for the 25 patients older than 70 years vs 3.3 cm3 (4.1 cm3) for the 39 patients younger than 70 years, P < .001.

Tumors with hyperostosis were significantly larger than tumors without hyperostosis (P = .031), but the growth rate was similar (Table 3). Meningiomas involving falx or venous sinuses demonstrated a trend toward higher growth rates (P = .086).

Gender, BMI, use of oral contraceptives, estrogen-replacement therapy, number of pregnancies or children, MRI T2-signal hyperintensity, calcification, tumor shape, and presence of peritumoral edema did not affect tumor growth rate significantly.

Tumor Td and Number of Doublings per Year

The mean tumor Td was 23.0 years (range, 0.3–396) and the number of tumor doublings per year was 0.4, ranging from 0 to 3.1. Tumor Td was higher for tumors larger than 4.2 cm3 (mean: 47.0 years; SD: 97 years) vs smaller tumors (mean: 11.6 years, SD: 31 years, P = .001). The calculation is based on tumor volume at baseline and at last follow-up. However, tumor Td was highly dependent on the follow-up interval chosen. None of the tumors displayed exponential growth with a constant Td. This finding is supported by the individual tumor growth curves (Fig. 2D).

Patterns of Tumor Growth

Investigating patterns of growth (excluding the 10 patients [15.6%] with only 2 evaluation time points), 5 principal growth curves were identified:

1) quasi-exponential growth,

2) linear growth,

3) sigmoid/self-limiting growth,

4) parabolic (reduction in volume after initial increase), and

5) continuous reduction (Fig. 2E).

Quasi-exponential growth pattern, that is, increasing growth rate with time, was observed in 14 patients (25.9%), constant/linear in 9 (16.7%), sigmoidal/self-limiting in 19 (35.2%), parabolic in 9 (16.7%), and continuous reduction in 3 (5.6%) of the tumors.

Of the 54 tumors with more than 1 follow-up, 33 (61.1%) displayed self-limiting growth (sigmoid, parable, or reduction), including 13 of 25 tumors that were eventually treated (52%) and 20 of 29 untreated tumors (69%). The mean follow-up time for tumors displaying self-limiting growth was significantly longer (P = .040) than for tumors with linear/semi-exponential growth (ie, 3.8 years [SD: 1.9] vs 2.8 years [SD: 1.6]).

Clinical Outcome/Symptomatic Growth

None of the patients in the prospective arm developed tumor-related symptoms during the study period.

Atypical Meningioma

Two (3.1%) of the 64 prospective patients were found to have atypical meningioma after surgical excision and histopathological examination. One patient displayed quasi-exponential growth whereas the other showed a sigmoid growth pattern.

Part 2–The Retrospective Study Arm

In the retrospective cohort, the median PFS (using a greater than 15% volume increase as an endpoint) was 6 years (95% CI 5.0–7.0). The life tables show 94.7% PFS at 1 year, 91.8% at 2 years, 79.9% at 3 years, 73.8% at 4 years, 61.0% at 5 years, and 16.3% at 10 years. Twenty-four of the meningiomas (63.2%) increased more than 15% and 26 (68.4%) more than 8.2%. Two (5.3%) tumors reduced more than 15% and 3 (7.9%) more than 8.2%. The mean overall tumor growth rate was 0.50 cm3 per year (95% CI 0.15 to 0.85, P = .005) (Fig. 2F).

Baseline Predictors for Fast Tumor Growth and Tumor Growth Curves

There was a significant correlation between growth rate and baseline tumor volume both as a continuous and a categorical variable (P < .001). The tumor growth rate increased by 0.15 (95% CI: 0.01 to 0.21) cm3 per year per cm increase in baseline tumor volume. There was no significant correlation between age and tumor growth rate (Table 3).

The growth-rate curve was quasi-exponential in 9 (23.7%), constant/linear in 4 (10.5%), sigmoidal/self-limiting in 8 (21.1%), parabolic (reducing after initial growth) in 3 (7.9%), and continuous reduction in 2 (5.3%). One tumor (2.6%) started to grow after initial volume reduction.

The clinical data obtained from the medical records of patients in the retrospective arm were limited and not suitable for analysis of symptom progression. One (2.6%) of the 38 retrospective patients was diagnosed with atypical meningioma after undergoing surgery. Three patients (7.9%) had died of unrelated causes.

Literature Review

We identified 20 retrospective studies evaluating the natural history of incidental meningiomas and predictors for growth. A total of 1557 patients were included. A summary of the studies is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Literature Review of 20 Retrospective Studies Evaluating Natural History and Predictors for Tumor Growth Including 1557 Incidental Meningiomas

| First Author, YearRef | No. of Patients | Mean Age (y) (Range) | Mean Follow-Up (Range) | Definition of TG (TD/TV Increase) | Total % TG | Symptomatic TG (%) | Median PFS, PFS at 3, 5 y (%) Mean Time to TG | GR/Tumor DT | Prognostic Factors for Increased GR | Recommendations Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romani, 201826 | 136 | 65 | 43 m | TD: 3 mm | 27.2 | 20 | – | – | Peritumoral edema MRI T2-hyperintensity No calcification |

Prospective studies needed |

| Kim, 20187 | C: 201 GKS: 153 |

57.5 | 57 m | TV: 30% | C: 70.1 GKS: 5.9 |

55.8 | PFS: 45 m (95% CI 60-74) 3-y PFS: 60.2 5-y PFS: 38.5 10-y PFS: 7.9 |

– | Young age MRI T2-hyperintensity No calcification |

Proactive GKS |

| Jadid, 201510 | 65 | 66.6 | 74 m | TD: 2 mm | 35.4 | – | 10-y PFS: 50% Median 2.9 y (range, 1-9 y) |

– | None | Re for young patients |

| Hashimoto, 201211 | 110 | 66.8 | 46.9 m | TV: 15% | 63 | Skull base: 2.6 Non–skull base: 8 | – | GR: 1.2 cm3/y DT: 112-181 m |

Non–skull base location | C for skull base tumors |

| Oya, 201113 | 244 | 60.5 | 3.8 y | TD: 2 mm TV: 8.2% |

TD: 44 TV: 70 |

– | 4-y PFS: 60% | GR: 0.05-0.53 cm3/y | Age <60 y Peritumoral edema MRI T2-hyperintensity No calcification Large volume Male gender Symptomatic |

C (closer follow-up if <60 y with tumors >25 mm with T2-hyperintensity and no calcification) |

| Rubin, 201114 | 56 | 64 | 65 m | – | 38 | 0 | Mean 63 m (range, 15-131 m) | GR: 4±3 mm/y | Young age No calcification |

C if >70 y until growth, Re if <70 y |

| Nakasu, 201116 | 31 | 57.5 | 7.5 y | TV: 8.2% | 74.2 | – | – | – | Young age No calcification WHO grade 1 |

Sigmoid TG rather than unlimited TG |

| Hashiba, 200912 | 70 | 61.6 | 39.3 m | TV: 15% | 62.9 | – | – | TD: 93.6 m | No calcification | Complex TG pattern, not always exponential |

| Nabika, 200717 | 36 | 72.1 | – | – | 30.6 | – | – | GR: 0.24 cm3/y | MRI T2 hyper-intensity No calcification |

C (based on radiology, GR and surgical accessibility) |

| Yano, 20068 | C: 351 R: 213 |

(17–88) | – | – | 37.3 | 6.4 | Mean 7.8 y (range, 5.2-12.9 y) |

GR: 1.9 mm/y | MRI T2-hyperintensity No calcification |

C to avoid surgical morbidity |

| Herscovici, 200415 | 43 | 65 | 67 m | TD: 2 mm | 37 | 0 | – | GR: 4 mm/y | Young age Sphenoid ridge location |

C if >60 y, Re if <60 and TG |

| Nakamura, 200331 | 47 | 60.9 | 43 m | – | – | – | – | GR: 0.796 cm3/y TD: 21.6 y |

Young age MRI T2-hyperintensity No calcification |

C until symptoms appear |

| Iwai, 200320 | 53 | 30.5 | 30.8 m | – | 43 | 3.7 | – | GR: 0.1 cm/ y | – | GKS for cavernous sinus meningioma |

| Kuratsu, 200024 | 63 | (22-88) | (12-96 m) | – | 31.7 | – | Mean 27 .8 m (range, 12-87 m) |

– | No calcification MRI T2-hyperintensity |

Re should be considered if <70 y |

| Yoneoka, 200025 | 37 | 61.0 | – | – | 24.3% >1 cc/y |

– | Mean 3.0 ± 0.5 y | – | Young age | C (the majority may be observed) |

| Niiro, 200019 | 40 | 76.1 | 38.4 m | TD: 5 mm | 35 | 12.5 | Mean 32.1 m (range, 10-88 m) |

– | Large tumor size No calcification |

C (at 2-3 m to rule out malignancy, then 6- to 12-m intervals in elderly) |

| Igarashi, 199923 | 23 | 47 | 5.1 y | – | – | 66.7 if TD >14 mm | – | – | Noncystic | C if cystic or TD <14 mm, closer follow-up if not |

| Go, 199822 | 29 | 67 | 74 m | – | 11.4 | 2.9 | – | – | No calcification | – |

| Olivero, 199521 | 45 | 66 | 32 m | – | 22.2 | 0 | Mean 47 m (range, 6 m-15 y) | GR: 0.24 cm/y | None | C |

| Firsching, 199018 | 17 | (43-83) | 21 m | – | – | – | – | GR: 3.6%/y | – | C |

| Present study | R: 38 P: 64 |

61 64 |

5.2 y 5 y |

TV: 15% TV: 15 % |

63.2 75 |

– 0 |

PFS: 6 y (95% CI 5-7) PFS: 2 y (95% CI 1-2.3) |

GR: 0.5 cm3/y GR: 0.33 cm3/y |

Large tumor size Large tumor size High age |

C C |

Abbreviations: C, conservative treatment; DT, tumor doubling time; GKS, Gamma Knife treatment; GR, tumor growth rate; m, months; P, prospective arm; PFS: progression-free survival; Re, resection; R, retrospective arm; TD, tumor diameter; TG, tumor growth; TV, tumor volume; y, years; –: not available.

Discussion

This study suggests that the majority of incidental meningiomas will eventually grow, usually within 3 years of diagnosis. However, the growth is usually slow and self-limiting. We observed 5 main growth patterns for meningiomas: quasi-exponential, linear, sigmoid, parabolic, and continuous reduction. Notably, more than 60% of the studied tumors were growing in a self-limiting (ie, continuous reduction, sigmoid, or parabolic growth) pattern. Similarly, the mean tumor Td was significantly longer in larger tumors compared to smaller tumors, indicating a slowing of the growth rate with a self-limiting growth pattern over time. The development and growth of meningiomas is clearly a dynamic process. Multiple volume measurements over an extended period of time are required to define the natural history. In this context 5 years of follow-up is relatively short, and therefore we believe the 5 patterns of growth observed could merely represent 5 stages in the natural history of meningiomas. In other words meningiomas might start growing in a quasi-exponential or linear pattern prior to entering a stage of self-limiting growth pattern (sigmoid or parabolic) followed by end-stage continuous shrinkage. A complex growth pattern for incidental meningiomas including sigmoid rather than exponential growth has previously been described by Hashiba et al12 and Nakasu and colleagues.11,12,16,32 Spontaneous reduction in meningioma size has been described earlier.33

There was a large discrepancy in PFS in the retrospective and the prospective arm, 6 vs 2 years, respectively. The prospective patients were followed with close 6-month intervals for the first 2 years and once yearly thereafter. In the retrospective arm the first follow-up was at 1, 2, or 3 years and the next follow-up interval varied from 1 to 7 years. Moreover, the total follow-up was often shorter than 5 years. The detection of tumor growth may thus have been missed completely or delayed in the retrospective arm. The large number of excluded patients and patients lost to follow-up in the retrospective arm may have led further to an underestimation of the primary endpoint and thereby explain the longer PFS observed. Measurement, inclusion, and lost to follow-up bias may also explain the generally longer PFS (ranging from 3.8 to 5.3 years) and lower percentage of tumor growth (ranging from 11.4% to 74.2%) reported in previous retrospective studies presented in Table 4 compared with our prospective arm.

We established that larger tumor volume is clearly associated with higher tumor growth rates despite longer tumor Tds in both arms of our study. This is consistent with earlier retrospective studies.13,19,24 Interestingly, in contrast with previous reports,13–16,25,32 we found that the growth rate was higher in older patients. This may reflect the fact that older patients generally have larger baseline tumor volumes and/or a lack of long-term follow-up in elderly patients in the previous retrospective studies. Several of these studies have identified young age as a predictor of faster tumor growth13–16,25,32 and advocated early treatment for younger patients.14,15 Our study does not support this view.

Previous studies also found higher growth rates associated with male gender,13 noncalcified tumors,8,12–14,16,17,19,22,24,32 noncystic tumors,23 high T2-signal intensity,8,13,17,32 and non–skull base location.11 We were unable to confirm the prognostic value of these factors in either arm of the present study. The significance of these reported risk factors varies markedly in the earlier studies and few are consistently reproduced. Calcification is the most consistent finding defining stable tumors. We could not demonstrate this in our study, but only a few patients in the prospective arm of the study underwent CT scans, which are more reliable than MRI in visualizing calcification. Thus, the importance of evaluating calcification of incidental meningiomas may be underestimated in our study.

A large prospective study and meta-analysis showed that estrogen-only menopausal hormone therapy significantly increases the risk of all CNS tumors, including meningioma. However, this was not seen with estrogen-progesterone hormone therapy.34 Similar to previous reports, our data set had a high female-to-male ratio, 2.8:1. We did not, however, find any correlation between tumor size or tumor growth rate and exposure to female hormones, including menopausal hormone-replacement treatment, contraceptives, number of pregnancies and children, or BMI. This lack of correlation might be due to a lack of statistical power.

To justify treatment of an asymptomatic benign lesion, the risk of developing neurological symptoms as a result of conservative treatment should exceed the risk of surgery or SRS. Even though the majority of the meningiomas grew over time, none of our patients developed tumor-related symptoms during follow-up. Most retrospective studies have demonstrated a low risk for symptomatic growth (2.6% to 12.5% of the patients), and the results of Olivero et al21 and Rubin and colleagues14 are in line with our data as none of their patients had symptomatic tumor growth.

The risk of a radiologically diagnosed meningioma being anaplastic (WHO grade 2) or malignant (WHO grade 3) is generally low: 5%,35 while 1 study reported one-fourth of growing incidental meningiomas to be atypical or malignant.36 In the present study, only 3% of the meningiomas turned out to be atypical in both arms of the study. None of these atypical meningiomas were symptomatic at the time of treatment and the indication for surgery was based solely on radiological progression.

The psychological burden associated with an untreated lesion has been an argument for early treatment.10 However, owing to the inherent tendency of meningioma to recur after surgical treatments, long-term postoperative follow-up will have a similar psychological impact as conservative management. Although no studies have investigated quality of life in these patients, incidental meningiomas have been shown not to impair neurocognition.37

In this age group concomitant serious medical conditions are relatively common. In the current study 6.3% and 7.9% died from other causes within the 5 years of follow-up in the prospective and retrospective arms, respectively. Poor general health or prognosis will often strengthen the argument for conservative management.

A Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology review1 of meningioma treatment concluded that incidental, asymptomatic, radiologically presumed meningiomas may be managed with observation, during which treatment may be withheld until symptoms develop, sustained growth occurs, or concerns of encroachment on sensitive structures arise. Thus, the decision to treat or observe an incidental meningioma depends on the surgeon’s preference usually based on the patient’s age, comorbidity, tumor size, growth rate, and proximity to eloquent area/critical structures. The European Association of Neuro-Oncology guidelines restate that there is no level-1 (randomized, controlled trials) or level-2 (prospective studies) evidence to support guidelines for observational management. They recommend MRI at 6 months, then annually for 5 years, and every second year thereafter based on level-3 evidence.38

Sughrue et al28 identified 22 published studies reporting on 675 patients with untreated meningiomas followed by serial MRI and recommended observation in the early course of treatment for small asymptomatic meningiomas, especially those with an initial diameter less than 2 cm. A review by Chamoun and colleagues29 concluded that 24.3% to 57.1% of asymptomatic meningiomas grow. It argued to reserve surgical interventions for large symptomatic lesions, documented tumor growth, and suspicion for malignancy based on imaging characteristics and/or patient’s medical history.

In line with several retrospective studies,8,13,17–19,21,23–25 our results support conservative management with close follow-up for all incidental meningiomas as radiological growth precedes symptom development in all patients independent of patient age, tumor volume, and location. Importantly, 25% of the meningiomas in our study remained unchanged or even reduced in size during the 5 years follow-up. In the present study, meningiomas were usually treated at the time of documented growth. However, more than half stabilized or reduced in size after initial growth before the time of treatment. Notably, 44% of the patients with growing tumors were managed by further observation. None of these individuals developed tumor-related symptoms. Our results demonstrate that a self-limiting growth pattern is the natural development of more than 60% of all meningiomas. This includes 52% of the treated meningiomas, thus one has to examine the growth carefully before treating. This denotes merit for conservative management until symptom development, as recommended by Nakamura et al.32 This will allow many tumors to reach their stabile size as shown in the recent study. We recommend close MRI follow-up every 6-12 months initially as most tumors progress within the first 3 years. Further follow-up intervals may be increased according to the initial growth pattern, patient age, and tumor size.

The theoretical increased risk of late treatment of asymptomatic but growing meningiomas vs early treatment must be addressed in future prospective, randomized trials. Only such trials stratified according to age, tumor location, size, and treatment strategy can evaluate the long-term outcome of conservative treatment until symptomatic growth vs early treatment.

We believe our study enhances the knowledge of the natural history of incidental meningioma as the first prospective data published with a high compliance and low drop-out rate. We acknowledge limitations of our study, including a relatively small number of patients and the nonrandomized design. However, these results provide level-2 evidence for recommending conservative treatment until documented growth and/or symptom devolvement for patients with radiologically verified meningioma within the age and size range of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the University of Bergen and Helse-Vest.

Acknowledgment

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies annual meeting October 1-5, 2017, in Venice, Italy; at the Congress of Neurological Sciences annual meeting, October 7-11, 2017, in Boston, MA, USA; and at the Leksell Gamma Knife Society Meeting Series, December 18, 2018, in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1. Rogers L, Barani I, Chamberlain M, et al. Meningiomas: knowledge base, treatment outcomes, and uncertainties. A RANO review. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(1):4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mawrin C, Chung C, Preusser M. Biology and clinical management challenges in meningioma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e106–e 115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Håberg AK, Hammer TA, Kvistad KA, et al. Incidental intracranial findings and their clinical impact; the HUNT MRI study in a general population of 1006 participants between 50-66 years. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1821–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakasu S, Hirano A, Shimura T, Llena JF.. Incidental meningiomas in autopsy study. Surg Neurol. 1987;27(4):319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20(1):22–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim KH, Kang SJ, Choi JW, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes of proactive Gamma Knife surgery for asymptomatic meningiomas compared with the natural course without intervention [published online ahead of print May 1, 2018]. J Neurosurg. doi: 10.3171/2017.12.JNS171943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yano S, Kuratsu J; Kumamoto Brain Tumor Research Group Indications for surgery in patients with asymptomatic meningiomas based on an extensive experience. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(4):538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohammad MH, Chavredakis E, Zakaria R, Brodbelt A, Jenkinson MD. A national survey of the management of patients with incidental meningioma in the United Kingdom. Br J Neurosurg. 2017;31(4):459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jadid KD, Feychting M, Höijer J, Hylin S, Kihlström L, Mathiesen T. Long-term follow-up of incidentally discovered meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015;157(2):225–230; discussion 230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashimoto N, Rabo CS, Okita Y, et al. Slower growth of skull base meningiomas compared with non–skull base meningiomas based on volumetric and biological studies. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(3):574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hashiba T, Hashimoto N, Izumoto S, et al. Serial volumetric assessment of the natural history and growth pattern of incidentally discovered meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(4):675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oya S, Kim SH, Sade B, Lee JH.. The natural history of intracranial meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(5):1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rubin G, Herscovici Z, Laviv Y, Jackson S, Rappaport ZH.. Outcome of untreated meningiomas. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13(3):157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herscovici Z, Rappaport Z, Sulkes J, Danaila L,Rubin G.. Natural history of conservatively treated meningiomas. Neurology. 2004;63(6):1133–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakasu S, Nakasu Y, Fukami T, Jito J, Nozaki K.. Growth curve analysis of asymptomatic and symptomatic meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2011;102(2):303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nabika S, Kiya K, Satoh H, Mizoue T, Oshita J, Kondo H.. Strategy for the treatment of incidental meningiomas [article in Japanese]. No Shinkei Geka. 2007;35(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Firsching RP, Fischer A, Peters R, Thun F, Klug N.. Growth rate of incidental meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1990;73(4):545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niiro M, Yatsushiro K, Nakamura K, Kawahara Y, Kuratsu J.. Natural history of elderly patients with asymptomatic meningiomas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):25–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, Morikawa T, et al. The treatment for asymptomatic meningiomas in the era of radiosurgery [article in Japanese]. No Shinkei Geka. 2003;31(8):891–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olivero WC, Lister JR, Elwood PW. The natural history and growth rate of asymptomatic meningiomas: a review of 60 patients. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(2):222–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Go RS, Taylor BV, Kimmel DW. The natural history of asymptomatic meningiomas in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1718–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Igarashi T, Saeki N, Yamaura A. Long-term magnetic resonance imaging follow-up of asymptomatic sellar tumors—Their natural history and surgical indications. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1999;39(8):592–598; discussion 598–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuratsu J, Kochi M, Ushio Y. Incidence and clinical features of asymptomatic meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(5):766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yoneoka Y, Fujii Y, Tanaka R. Growth of incidental meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142(5):507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Romani R, Ryan G, Benner C, Pollock J. Non-operative meningiomas: long-term follow-up of 136 patients [published online ahead of print June 6, 2018]. Acta Neurochir (Wien). doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abeloos L, Lefranc F. What should be done in the event of incidental meningioma? [article in French] Neurochirurgie. 2011;57(2): 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, Aranda D, Barani IJ, McDermott MW, Parsa AT.. Treatment decision making based on the published natural history and growth rate of small meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(5):1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chamoun R, Krisht KM, Couldwell WT. Incidental meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31(6):E19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fountain DM, Soon WC, Matys T, Guilfoyle MR, Kirollos R, Santarius T.. Volumetric growth rates of meningioma and its correlation with histological diagnosis and clinical outcome: a systematic review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017;159(3):435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Breslow NE,, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakamura M, Roser F, Michel J, Jacobs C, Samii M. The natural history of incidental meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(1):62–70; discussion 70-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hirota K, Fujita T, Akagawa H, Onda H, Kasuya H.. Spontaneous regression together with increased calcification of incidental meningioma. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benson VS, Kirichek O, Beral V, Green J.. Menopausal hormone therapy and central nervous system tumor risk: large UK prospective study and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(10):2369–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kasuya H, Kubo O, Kato K, Krischek B.. Histological characteristics of incidentally-found growing meningiomas. J Med Invest. 2012;59(3-4):241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Butts AM, Weigand S, Brown PD, et al. Neurocognition in individuals with incidentally-identified meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2017;134(1):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goldbrunner R, Minniti G, Preusser M, et al. EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of meningiomas. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):e383–e391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]