Abstract

Background/Aim: A prospective randomized open label parallel trial, comparing the quality of life (QoL) after endoscopic placement of a self-expandable metal stent or primary tumor resection, in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer was performed. Patients and Methods: Thirty-three patients affected with stage IV colorectal cancer and unresectable metastases were randomly assigned into two groups: Group 1 (16 patients), that underwent self-expandable metal stent positioning and Group 2 (17 patients), in which primary tumor resection was performed. Karnofsky performance scale and QoL assessment using the EQ-5D-5L™ questionnaire was administered before treatment and thereafter at 1, 3 and 6 months. Results: At 1 month, index values showed a statistically significant deterioration of the QoL in patients of Group 2 when compared to those of Group 1 (p=0.001; 95%CI=0.065-0.211) whereas, at 6 months, index values showed a statistically significant deterioration of the QoL in patients of Group 1 (p<0.025; 95%CI=0.017-0.238). Conclusion: QoL in patients affected with stage IV colorectal cancer has a bimodal fluctuation pattern: at 1-month it was better in patients that received stent, but at 6-months it was significantly better in patients submitted to surgical resection.

Keywords: Advanced colorectal cancer, surgical resection, endoscopic stent positioning, targeted therapy

Colorectal cancer is a commonly diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of death in Italy. More than 25% of the patients present with an initial diagnosis of stage IV cancer. Simultaneous resection of the primary tumor and metastases, although conceptually curative, is unfeasible in more than 80% of the patients because they are affected with unresectable metastases (1-3). Median overall survival managed with best supportive care alone is about 5 to 6 months (4). Conversely, systemic therapy provides meaningful improvements in median survival and progression-free survival. Overall, with the judicious use of novel cytotoxic and biological agents (5-8), the median overall survival has been extended to approximately 2 years (9-11).

Despite the optimal improvement in survival with the use of novel cytotoxic and biological agents, these patients might present with symptoms of subacute large bowel obstruction, which mandate a palliative treatment either surgical or endoscopic.

Quality of life (QoL) is crucial to evaluate the appropriateness of the various treatment modalities especially in patients affected with advanced colorectal cancer because major complications related to the primary tumor, metastases and therapy with novel cytotoxic and biological agents might be directly linked with a significant adverse effect on QoL. Theoretically, a non-invasive intervention with an estimated low complication rate could potentially result in a favorable QoL as a result of better tolerance. The effects on QoL in patients with metastatic stage IV colorectal cancer has been evaluated in studies of various designs, and in different settings (12-14). Well established questionnaires give the opportunity to include many patients and reach reliable and validated results in a practical manner. These studies give the opportunity to explore patient’s experiences in an in-depth manner.

QoL assessment of patients affected with stage IV colorectal cancer should be a priority in order to propose a personalized treatment for each patient. Improvement in the median survival rate associated with a good perceived QoL is the goal to be achieved.

A prospective randomized open label parallel trial, comparing the QoL after endoscopic placement of a self-expandable metal stent or after primary tumor resection, in patients affected with stage IV colorectal cancer and symptoms of subacute bowel obstruction was performed.

Patients and Methods

All patients presenting with stage IV colorectal cancer and unresectable metastases at our Institution from February 2013 to January 2019 were enrollment into this prospective randomized open label parallel trial. All analyses were carried out according to the principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and a formal ethic approval from our Institutional Research Committee was obtained. The protocol was properly registered at a public trial registry, www.clinicaltrials.gov (Trial identifier NCT03451643). A written informed consent for the treatment and the analysis of data for scientific purposes was obtained from patients.

A computerized database was then created to prospectively collect all clinical, pathological, intra- and post-operative outcomes, quality of life (EQ-5D™) and long-term survival.

Inclusion criteria were: aged less than 85 years, pre-treatment histological diagnosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma, computed tomographic (CT) scan showing unresectable metastases, symptoms of subacute large bowel obstruction (defined as continued passage of flatus and/or fecis beyond 6-12 h after the onset of symptoms namely colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and abdominal distension relieved by conservative treatment), lumen reduction ranging between 70% and 99% at colonoscopy, a Karnofsky Performance Scale Index (15) greater than 60%.

Criteria for exclusion were a white blood cells count less than 4,000/l, a platelet count less than 70,000/l, patients with renal failure (i.e. albumin to creatinine ratio >30 mg/mmol and estimated glomerular filtration rate <30-44 ml/min/1.73 m2), patients with major alterations in liver function tests (i.e. total bilirubin >25.6 μmol/l, AST >5 U/l, ALT >5 U/L, PT-INR >1.5).

Out of 70 patients with Stage IV colorectal cancer, unresectable metastases and symptoms of subacute large bowel obstruction, 33 were enrolled in the present trial. The remaining 37 patients were excluded from the study because of a poor Karnofsky Performance Scale Index (19 patients), serum bilirubin levels above 25.6 μmol/l (11 patients), low platelet and white blood cell count (6 patients), and renal insufficiency (7 patients). In 15 patients there were more than one of the above-mentioned reasons to be excluded from the study and 9 of them also refused to have surgery. The remaining 33 patients were randomly assigned into two treatment groups: Group 1 comprised 16 patients who underwent placement of a self-expandable metal stent and Group 2 comprised 17 patients who received primary tumor resection.

Endoscopic stenting. Bowel preparation consisted of 1 l of water with PLENVU® (polyethylene glycol 3350, sodium ascorbate, sodium sulfate, ascorbic acid, sodium chloride and potassium chloride for oral solution) powder administered according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Few hours before the endoscopy a low-pressure water enema was performed. The procedure was performed under light sedation with benzodiazepine at a dosage dependent on the patient’s body weight.

Briefly, we adopted a modification of previously described techniques; a pediatric nasogastroscope (4.8 mm in diameter) was used to pass the obstruction (16,17). Under direct vision, the guidewire was passed through the nasogostrocope above the obstructed bowel segment (18). Fluoroscopy was also used to follow the course of the guidewire and the deployment of the stent. The time during which fluoroscopy was used was much shorter than the time required with the standard technique. This made the procedure much simpler, faster, and theoretically with reduced risk of perforation or bleeding. The SEMS apparatus (Precision Stent System Microvasive, Boston Scientific Corporation, Boston, MA, USA) was placed at the level of the obstruction through the previously inserted guidewire, and was finally deployed under fluoroscopic guidance. The length of the stent ranged from 9 to 12 cm. We used uncovered stents: initially Ultraflex OTS stent, and later Wallflex TTS stents (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA, USA). The majority of the patients had one stent placed. In one patient two stents were required.

Surgery. Open surgery was performed in 14 patients, and laparoscopic surgery in three patients, after colonic preparation (as described above). No terminal colostomy or ileostomy was performed.

Chemotherapy. The patients received chemotherapy with leucovorin (400 mg/m2) and 5-fluorouracil (2 g/m2). Patients with wild type K-Ras received also bevacizumab (26 patients). Twenty patients received also cetuximab, associated (16 patients) or not (4 patients) to bevacizumab. Bevacizumab was infused at a dosage of 5 mg/kg every two weeks, cetuximab was infused at a dosage of 250 mg/m2 every two weeks, followed by leucovorin at the dosage of 400 mg/m2 over 2 h. The treatment was immediately followed by 5-fluouracil at a dosage of 2 g/m2.

Karnofsky performance scale and Quality of life (QoL) assessment. The Karnofsky performance scale (19) was used to reclassify patients’ functional impairment after treatment. The EQ-5D-5L™ questionnaire (©EuroQol Group, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) was administered before treatment and thereafter at 1, 3 and 6 months in order to measure the QoL of our patients after the endoscopic or surgical treatment in the following areas of investigations (mobility, self-care activities, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/ depression) with each dimension graded into 5 levels (i.e., no problem/slight problem/moderate problem/severe problem/ extreme problem). The health state can therefore be defined by a 5-digit number by combining one level from each of the five dimensions and then converted into the EQ-5D-5L index values according to the data from the general Italian population matched for age (20). Furthermore, to help patients explain how good or bad their health state was, a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS™) with endpoints labelled “the best health you can imagine” graded 100 and “the worst health you can imagine” graded 0 was administered and the results were furtherly analyzed.

Follow-up evaluation. Patients were followed-up on an outpatient basis every month. Hematochemical tests, abdominal CT scan and chest X-ray were performed every three months for the first year, and thereafter every year.

Statistical analysis. We analyzed our data with a computer software program (SPSS Ver. 25.0.0.1; SPSS Chicago, IL, USA for MacOS High Sierra ver. 10.13.4, Apple Inc. 1983-2018 Cupertino, CA, USA). Due to sample sizes, non-parametric tests were applied. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyze continuous variables. The Chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Due to the heterogeneity of the sample, data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, median, interquartile range (IQR) and mode (21). Actuarial survival rate was assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method at 1-year. Standard error (SE) of survival rate was estimated at each censored case. Actuarial survival was limited at 1-year because analysis of longer time periods was statistically inappropriate due to the small number of patients and the consequent high standard deviations. Cox regression analysis was applied to assess the influence of demographics, clinical data and hematological tests on survival rates. Variables that significantly differed at the level of significance <0.05 (chemotherapy suspension) were entered into the model, and the quality of their fit was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Differences with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

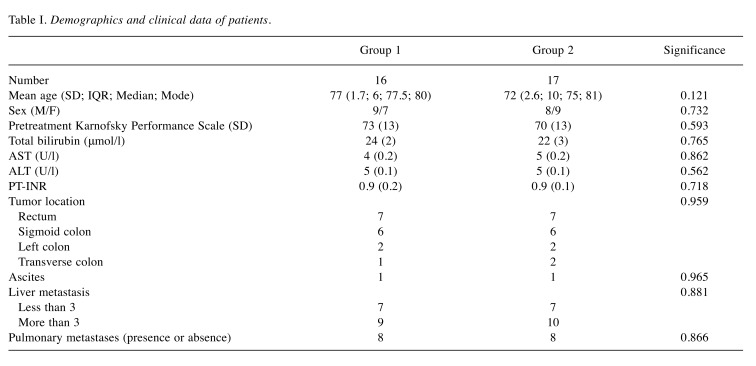

Demographics and clinical findings. There were 17 males and 16 females. Mean age at presentation was 74.4±1.6 years (min. 44-max. 89 years; median 76 years; IQR 9; mode 76). Demographic and clinical data of the two groups are summarized in Table I. No significant differences among the two groups were noted. The educational status of our population was similar. The majority of them (22-67%) had a basic education (primary, intermediate and secondary) and 11 (33%) had college or master of science education.

Table I. Demographics and clinical data of patients.

Early results. There was no postoperative mortality or major complications within 30 days. Overall, we recorded a minor complication; ne patient in Group 1 had rectal bleeding for 2 days which spontaneously resolved. Oral feeding was resumed significantly earlier in Group 1 patients when compared to Group 2 patients (p<0.001; 95%CI=–1.847 - –1.329).

Overall length of stay was 7±3.6 days (min. 2-max. 19; mode 3 days, IQR 6). Hospitalization was significantly shorter in Group 1 (mean 4±1.4 days; min. 2-max. 8) when compared to Group 2 patients (mean 9.8±2.6 days; min. 7-max. 19) (p<0.001; 95%CI=–7.401 - –4.364).

Long-term results. No patients were lost to follow-up (mean 9.7±4.2 months; min. 4-max. 20; mode 5 months, IQR 6). There were no major or life-threatening complications related to chemotherapy, but five (15%) patients stopped chemotherapy because of a significant deterioration in the liver function tests after the first cycle. Symptoms, potentially related to chemotherapy (fatigue, partial hair loss, decreased liver function) were common (60%-20 patients), and equally distributed in the two groups (12 Group 1 and 8 Group 2).

No differences were observed in survival rates among the two groups (p=0.234). One-year actuarial survival rate of Group 1 was 25% (SE=0.10) whereas in Group 2 was 29% (SE=0.11).

Factors influencing survival. Cox regression analysis showed that suspension of chemotherapy because of deterioration of liver function tests was the most important factor negatively influencing survival (p<0.002; OR=9.490; 95%CI=2.258- 39.885). Patients who stopped chemotherapy died within 5 months. Overalls seven patients had longer than 1-year survival (2 in Group 1 and 5 in Group 2).

Karnofsky performance scale and Quality of Life (QoL). Preoperative Karnofsky performance scale used to classify patients’ functional impairment showed no difference between the two groups (73±13 and 70±13, respectively for Group 1 and 2; p=0.533; 95%CI=–7.043-12.117). A significant difference in the Karnofsky performance scale was observed at 1 month (65±11 and 56±12, respectively for Group 1 and 2; p=0.032; 95%CI=0.837-17.398), whereas no differences were recorded at 3 and 6 months (3 months: 61±9 and 58±8, respectively for Group 1 and 2; p=0.335; 95%CI=–3.264-9.294. 6 months: 58±6 and 52±9, respectively for Group 1 and 2; p=0.132; 95%CI=–1.733- 12.382). Harmonized to the Italian population, preoperative index values were similar among the groups (p=0.911; 95%CI=–0.055-0.062). At 1-month, index values showed a statistically significant deterioration in the QoL of patients in Group 2 when compared to those in Group 1 (p=0.001; 95%CI=0.065-0.211). Index values were similar among the two groups at 3 months (p=0.079; 95%CI=–0.007-0.119). At 6 months, index values showed a statistically significant deterioration in the QoL of patients in Group 1 when compared to those in Group 2 (p<0.025; 95%CI=0.017- 0.238). Visual analog scale showed that there is no variation in the two groups of patients between the preoperative and postoperative period at 1, 3 and 6 months.

Discussion

Despite the increased public attention to screening and the awareness of the importance of early diagnosis, several patients present with advanced colorectal cancer and unresectable metastases at the time of diagnosis (1,2); 10 to 20% have also symptoms of subacute large bowel obstruction and 8 to 29% of complete obstruction (22). Surgery conducted for these patients has a 15 to 20% death rate and a 50% complication rate (23).

Retrospective data seem to favor a noncurative resection of the primary tumor in advanced colorectal cancer patients with minimal symptoms, Ahmed et al. (24) showed, in fact, a hazard ratio for survival of 0.67 for minimally symptomatic patients versus 0.75 for symptomatic patients. In patients with symptoms of subacute large bowel obstruction, controversies exist about the role of primary tumor resection. Several studies have reported that the median and overall survival rates can be increased by using chemotherapy alone without removing the primary lesion (25-30). In addition, stent insertion, which is expected to develop fewer complications, is restrictively chosen to relieve the symptoms of the obstructive lesion (31). Our main goal was to provide optimal palliation in terms of QoL and proper comprehensive treatment. Our patients were aware of their advanced disease. We are aware that QoL and patient’s perception of the disease and the imminent death are complex areas to study. Therefore, use of literature reviews and combining studies with different methods, studying closely related aims, can strengthen the evidence, thus the areas where knowledge is lacking, can be identified. The studies measuring QoL should use the same design, relevant samples, repeated measures and validated questionnaires. Our study, although it had a small sample size, used validated questionnaires with repeated measures and all patients completed the surveys. We presumed that in our patients, although they felt safe being under surveillance, education and comprehension of the disease might have caused additional insecurity and concerns among some of them.

Patients who received a a self-expandable metal stent reported a better QoL at an earlier time point, because of an early recovery and rapid discharge from the hospital. Conversely, a longer hospitalization and delayed oral feeding of patients who underwent surgery, negatively influenced the QoL at 1-month. Obviously, the laparoscopic approach, which is associated with a shorter hospitalization, faster refeeding, less postoperative pain and rapid resume to daily activities might, at least theoretically, improve 1-month QoL (32-36). However, in our series the majority of patients underwent an open palliative tumor resection. We choose an open approach because preoperative studies have demonstrated local invasion with infiltration of the surrounding structures, thus increasing the risk of a laparoscopic resection.

In our study we also found that patients who had resection of the primary tumor had better QoL 6 months after surgery. This result might be related to the presence of a specific symptomatology related to the metal stent positioning i.e. tenesmus, incomplete evacuation and small rectal bleeding. In addition, in this group of patients the persistence of the colorectal tumor may associate with an even shorter life-expectancy.

The results of this study are important to define the optimal therapeutic strategy. Patients eligible for systemic chemotherapy should be submitted to endoscopic stent positioning to avoid delays in chemotherapy administration, whereas surgery should be proposed to patients with contraindication to chemotherapy in order to guarantee a better QoL at mid-term. This schema is proposed because resection of the primary tumor combined with targeted therapy, had a beneficial role in the survival of our patients.

In our series, visual analog scale was unable to offer significant data on QoL. We believe that this was due to the difficulty of the patients with fluctuations in their discomfort perception of the advanced terminal disease to express in a numeric scale their real physical and mental status. Patients may have difficulties to judge how to rate their discomfort on the visual analog scale line (37).

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, this is a single-center study with a small number of patients and with significant heterogeneity in the presentation of stage IV colorectal cancer. Secondly, life expectancy in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer and altered liver function is significantly reduced and an aggressive surgical and chemotherapeutic approach can negatively affect QoL and survival.

In conclusion, QoL of patients affected with stage IV colorectal cancer with symptoms of bowel obstruction has a bimodal fluctuation pattern: at 1-month it was better in patients that received stent but at 6-months it was significantly better in patients submitted to surgical resection.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Enrico Fiori (Conception, design and data analysis), Antonietta Lamazza (Analysis and interpretation of data), Antonio V. Sterpetti (Conception, design and data analysis), Daniele Crocetti (Analysis, interpretation of data and writing the manuscript), Francesca De Felice (Conception and design), Marco di Muzio (Collection of data), Andrea Mingoli (Conception design and data analysis), Paolo Sapienza (Conception, design and writing the manuscript), Giorgio De Toma (Conception and design).

References

- 1.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. PMID: 24639052. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson AB, Arnoletti JP, Bekaii-Saab T. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Colon Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(11):1238–1290. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0104. PMID: 22056656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiori E, Lamazza A, De Cesare A, Bononi M, Volpino P, Schillaci A, Cavallaro A, Cangemi V. Palliative management of malignant rectosigmoidal obstruction. colostomy vs endoscopic stenting. a randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(1):265–268. PMID: 15015606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheithauer W, Rosen H, Kornek GV. Randomised comparison of combination chemotherapy plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. BMJ. 1993;306(6880):752–755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6880.752. PMID: 7683942. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.306.6880.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poultsides GA, Servais EL, Saltz LB. Outcome of primary tumor in patients with synchronous Stage IV colorectal cancer receiving combination chemotherapy without surgery as initial treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(20):3379–3384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9817. PMID: 19487380. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCahill LE, Yothers G, Sharif S. Primary mFOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab without resection of the primary tumor for patients presenting with surgically unresectable metastatic colon cancer and an intact asymptomatic colon cancer: definitive analysis of NSABP trial C-10. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(26):3223–3228. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4044. PMID: 22869888. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ. K-RAS mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. PMID: 18946061. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu CY, Bailey CE, You YN. Time trend analysis of primary tumor resection for stage IV colorectal cancer. Less surgery improved survival. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(3):245–251. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2253. PMID: 25588105. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tournigand C, André T, Achille E. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):229–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.113. PMID: 14657227. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. PMID: 15175435. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. PMID: 19339720. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laghousi D, Jafari E, Nikbakht H. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among patients with colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(3):453–461. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.02.04. PMID: 31183195. DOI: 10.21037/jgo.2019.02.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pattamatta M, Smeets BJJ, Evers SMAA. Quality of life and costs of patients prior to colorectal surgery. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;17:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2019.1628641. PMID: 31190575. DOI: 10.1080/14737167.2019.1628641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques RP, Heudtlass P, Pais HL. Patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life for cetuximab versus bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: a prospective cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145(7):1719–1728. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02924-0. PMID: 31037398. DOI: 10.1007/s00432-019-02924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: Reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncology. 1984;2(3):187–193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187. PMID: 6699671. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamazza A, Fiori E, Schillaci A, Sterpetti AV. A new technique for self-expandable metal stent placement in patients with colorectal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(3):1045–1048. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2522-y. PMID: 30300253. DOI: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamazza A, Sterpetti AV, De Cesare A. Endoscopic placement of self-expanding stents in patients with symptomatic leakage after colorectal resection for cancer: long term results. Endoscopy. 2015;47(3):270–272. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391403. PMID: 25668426. DOI: 10.1055/s-0034-1391403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamazza A, Fiori E, Sterpetti AV. Self expanding metal stents in the treatment of benign anastomotic stricture after rectal resection for cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(4):150–153. doi: 10.1111/codi.12488. PMID: 24206040. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York. Columbia University Press. 1949:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scalone L, Cortesi PA, Ciampichini R. Italian population-based values of EQ-5D health states. Value Health. 2013;16(5):814–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.008. PMID: 23947975. DOI: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitley E, Ball J. Statistics review 1: presenting and summarizing data. Crit Care. 2002;6(1):66–71. doi: 10.1186/cc1455. PMID: 11940268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JH, Shon DH, Cahng BI. Complete single stage management of left colon cancer obstruction with new devices. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(5):1381–1387. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8232-3. PMID: 16151681. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-004-8232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JY, Kim JS, Hur H. Complication and relevant factors after an ileostomy for fecal diversion in a patient with rectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2009;25:81–87. DOI: 10.3393/jksc.2009.25.2.81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed S, Shahid RK, Leis A. Should non curative resection of the primary tumor be performed in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(5):420–441. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1469. PMID: 24155639. DOI: 10.3747/co.20.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(16):2938–2947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2938. PMID: 10944126. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham D, Pyrhönen S, James RD. Randomised trial of irinotecan plus supportive care versus supportive care alone after fluorouracil failure for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998;352(9138):1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02309-5. PMID: 9807987. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. PMID: 15175435. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiori E, Lamazza A, De Masi E. Association of liver steatosis with colorectal cancer and adenoma in patients with metabolic syndrome. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(4):2211–2214. PMID: 25862880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polistena A, Cucina A, Dinicola S. MMP7 expression in colorectal tumours of different stages. In Vivo. 2014;28(1):105–110. PMID: 24425843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tebala GD, Natili A, Gallucci A, Brachini G, Khan AQ, Tebala D, Mingoli A. Emergent treatment of complicated colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:827–838. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S158335. PMID: 29719419. DOI: 10.2147/CMAR.S158335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruo L, Gougoutas C, Paty PB. Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(5):722–728. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00136-4. PMID: 12742204. DOI: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polistena A, Cavallaro G, D'Ermo G. Clinical and surgical aspects of high and low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery in laparoscopic resection for advanced colorectal cancer in elderly patients. Minerva Chir. 2013;68(3):281–288. PMID: 23774093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crocetti D, Cavallaro G, Tarallo MR, Chiappini A, Polistena A, Sapienza P, Fiori E, De Toma G. Preservation of left colic artery with lymph node dissection of IMA root during laparoscopic surgery for rectosigmoid cancer. Results of a retrospective analysis. Clin Ter. 2019;170(2):e124–e128. doi: 10.7417/CT.2019.2121. PMID: 30993308. DOI: 10.7417/CT.2019.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crocetti D, Sapienza P, Sterpetti AV. Surgery for symptomatic colon lipoma: a systematic review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(11):6271–6276. PMID: 25368224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crocetti D, Sapienza P, Pedullà G, De Toma G. Reducing the risk of trocar site hernias. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96(7):558. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2014.96.7.558. PMID: 25245752. DOI: 10.1308/rcsann.2014.96.7.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cisano C, Sapienza P, Crocetti D, de Toma G. Z-entry technique reduces the risk of trocar-site hernias in obese patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98(5):340–341. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0114. PMID: 27087329. DOI: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faiz KW. VAS--visual analog scale. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2014;134(3):323. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.13.1145. PMID: 24518484. DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.13.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]