Abstract

Background: The aetiology of urgency urinary incontinence is a matter of debate. Current treatment options are based on the hypothesis of a neurological disorder of bladder innervation. However, it has also been hypothesised that one main cause is the reduced function of the bladder-holding apparatus, that is, insufficient suspension of the vesico-urethral junction. This study compared the effects of surgical apical vaginal elevation with those of solifenacin on urgency urinary incontinence in women. Patients and Methods: Women with mixed and urgency urinary incontinence were randomised to either an established pharmacological arm (10 mg/day solifenacin) or the surgical arm (bilateral uterosacral ligament replacement, cervicosacropexy, CESA; or vaginosacropexy, VASA. Clinical and objective outcomes were assessed at 4 months after each type of intervention. Results: The study was terminated early; 55 patients were operated on and 41 patients received pharmacological treatment. After surgical treatment, 23 patients (42%, 95% confidence intervaI=29-55%) became continent compared to four patients (10%, 95% confidence intervaI=1-19%) during solifenacin treatment. Conclusion: Compared to pharmacological treatment, the surgical repair of the apical vaginal end restored urinary continence in significantly more patients.

Keywords: Urgency urinary incontinence, mixed urinary incontinence, uterosacral ligaments, pelvic organ prolapse, cervicosacropexy (CESA), vaginosacropexy (VASA)

The aetiology and pathophysiology of urinary incontinence (UI) in women are controversial. Stress UI (SUI) can effectively be treated with the surgical application of suburethral tapes; urgency UI (UUI) is considered a neurological dysfunction of bladder innervation and is predominantly treated with different medications, including anticholinergic agents (1-3). Invasive treatment options for UUI, including botulinum toxin A or sacral nerve stimulation, inhibit the depolarisation of the detrusor muscle, resulting in ‘chemical denervation’ of the bladder or induction of somatic afferent inhibition of sensory processing in the spinal cord, respectively (4,5). In contrast to these inhibitions of detrusor muscle function, the aim of surgical treatment should be stabilisation of the bladder-holding apparatus (6-8).

In quadrupeds, the bladder lies in the front abdomen, and the urethra is located above the level of the bladder in the upper part of the vagina. The vagina itself has no supportive function for the bladder (9). By contrast, the upright body position leads to a sudden reversal of conditions in humans, that is, the level of the urethra lies below the bladder. Consequently, the bladder lies on the anterior vaginal wall, which is stabilised by the cervix (uterus) and its holding apparatus. Considering these anatomical conditions, the bladder base, and thus the transition from the bladder to the urethra (vesico-urethral junction), rests on the upper anterior vagina. A prolapse of this upper anterior vaginal wall or ‘lowering’ in this area can therefore lead to dysfunction (opening of the vesico-urethral junction) and involuntary loss of urine.

As many surgeries for prolapse restored urinary continence, it was hypothesised that resolving UI as well as continence is dependent on the intact fixation of the upper vagina (10,11). According to DeLancey, Ulmsten and Petros, SUI and UUI arise from the same anatomical defect: the laxity of the anterior vaginal wall (6-8). However, due to different surgical apical fixations and thus a lack of standardisation, these urinary continence-restoring effects are difficult to reproduce and evaluate. These surgeries were limited to patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP), and the continence-restoring effects were considered as positive ‘side-effects’.

The bony dimensions of the small pelvis are almost identical among women of different ethnicities; thus, the surgical procedure can be standardised (12,13). In the treatment of SUI, suspension of the lower anterior vaginal wall (suburethral part) through tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tapes (TOT) has been successful (14-16). Assuming that stretch receptors are located at the bladder base, this area corresponds to the upper part of the vagina. In the case of UUI, these receptors are stretched prematurely and lead to urgency (17).

To stabilise the base of the bladder, the apical vaginal end should be suspended first. Descending or ‘lowering’ of the uterus, therefore, leads to a change in tensioning of the vagina and its anterior wall. The vagina itself is practically suspended between the cervix and introitus similar to a hammock, and any laxity of the upper vaginal wall might lead to opening of the vesico-urethral junction.

The uterosacral ligaments (USL) are the main holding structures of the cervix in the small pelvis. To restore the physiological fixation of the apical vagina, standardised surgical procedures have been developed to replace the USL bilaterally. Depending on the presence of the uterus, these procedures are called cervicosacropexy (CESA) and vaginosacropexy (VASA). By replacing the USL with polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) tapes of identical lengths and shape at identical anatomical fixation sides, the anterior vaginal wall can be elevated, supporting the bladder base and bladder neck (18,19). Notably, this surgical procedure led to urinary continence in a considerable number of patients with mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) or UUI (12,20-22).

We hypothesised that in patients with UUI, elevation of the vagina would reduce the premature stretching of the bladder base and thereby reduce urgency. To investigate the effect of apical fixation on UUI symptoms, we conducted this randomised clinical trial (URGE 1 study). The effects of standardised bilateral USL replacement (CESA and VASA) on UUI were compared with those of standard pharmacological treatment (solifenacin). The main study aim was the re-establishment of urinary continence through either method. This study was approved by the local Ethical Committee, and all patients were aware of its experimental character.

Patients and Methods

Women with UUI or MUI who consulted the Division of Urogynaecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Cologne (tertiary unit), between November 2012 and June 2016 for primary treatment were requested to participate in the study. Clinical evaluation included medical history, frequency and volume charts, measurement of postvoid residual urine, urine analysis, and pelvic floor ultrasound. POP was defined according to the Pelvic Organ Quantification (POP-Q) system described by Bump et al. (23). In addition, digital palpation was performed with the patients in the standing position.

UI was determined based on the patient’s subjective complaints, rather than on urodynamic studies (which could not routinely be conducted for all patients). All patients were requested to complete validated UI questionnaires from the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence (ICIQ-UI) (24), and Urgency Perceptive Score (25) and the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score were calculated (26). The clinical diagnoses of SUI, UUI, and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) were based on the patients’ responses to the questions in the ICIQ-SF questionnaire. To obtain more detailed information, we deliberately decided to add some questions on micturition frequency and type of urine loss. Therefore, the clinical diagnoses were defined using question 4 in the ICIQ-SF questionnaire (‘When does urine leak?’), as follows: SUI was diagnosed if the patient had urinary leakage on coughing, sneezing, or physical activity/exercise; UUI was diagnosed as involuntary urinary leakage without physical activity or if patients had urinary leakage before they could reach the toilet in time. For statistical evaluation, the patients were requested to describe their urge to urinate, which was categorised as follows: ‘I am usually not able to hold urine’ (category: <3 minutes), ‘I am usually able to hold urine until I reach the toilet if I go immediately’ (category: 3 to <10 minutes), and ‘I am usually able to finish what I am doing before going to the toilet’ (category: >10 minutes). MUI was diagnosed if the patient had both SUI and UUI (24).The patients were classified as ‘continent’ if there were no symptoms of UI postoperatively.

Women with UUI or MUI, no prior urogynaecological surgery, and POP-Q stage 0 and 1 were included in this study. Patients with SUI only, with prior urogynaecological surgery (including suburethral slings, colposuspension, anterior colporrhaphia, apical fixation, intravesical botulinum toxin A injections and sacral neuromodulation), or prior pharmacological therapy were excluded from this study.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The patients were informed about the experimental nature of the study. Based on the results of previous studies, patients were informed of the likelihood of restoration of urinary continence being approximately 40% after CESA and VASA (12). If there was no improvement afterwards, they were to receive the standard pharmacological medication. Furthermore, it was explained to them that in the case of failure after CESA or VASA surgery, there was the possibility of TOT placement, with an overall continence rate of 76% (21).

The patients were randomised to the standard or control arm according to the random generated randomisation list (www.random.org/lists/) provided by the study coordinator. Due to the nature of this study, in which a comparison was made between the participants taking medication and those undergoing surgery, a double-blind design was not possible. To maintain blinding in these circumstances, the investigator and the participants were blinded to the knowledge of who was to undergo each type of intervention until after they had been examined. On the basis of sample size calculation, 120 patients were required to be randomised to either the standard arm (pharmacological treatment) or control arm (bilateral USL replacement CESA and VASA surgery). The patients in the standard arm received 10 mg/day solifenacin for 4 months, whereas those in the control arm underwent bilateral USL replacement. The patients were examined 2, 4, 8, and 16 weeks after the start of each intervention. The subjective and objective outcomes at week 16 were included in analysis.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne, Germany, on November 6, 2012 (no: 11-016). This study was registered under the clinical trial identifier NCT01737411 (Surgical vs. Medical Treatment of Urge Urinary Incontinence in Women). In autumn 2016, the study had to be terminated because most patients opted to undergo laparoscopic CESA or VASA. On the basis of these data, the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty agreed to the early termination of the study, after the randomisation of 96 patients at the end of 2016.

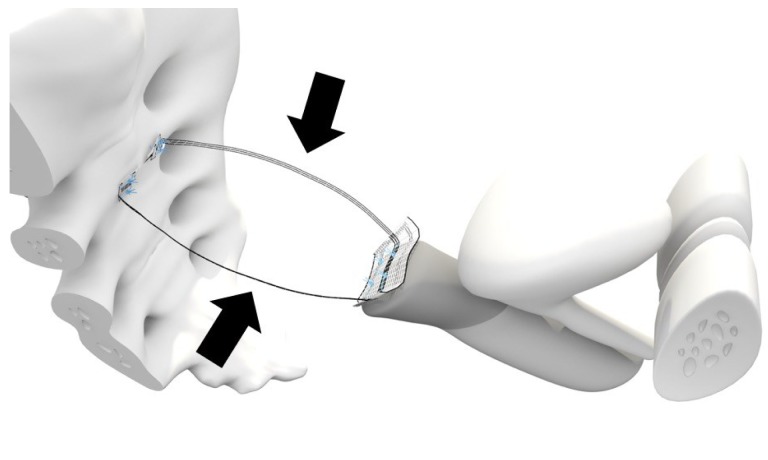

CESA and VASA are surgical techniques developed to standardise the restoration of the physiological fixation of the apical vagina, thereby supporting the bladder base. Specifically, designed PVDF structures of defined lengths (Dynamesh CESA: 8.8 cm, Dynamesh VASA: 9.3 cm, FEG, Aachen, Germany) and shape (width 0.4 cm) were placed in the peritoneal fold of the left and right USL. These PVDF structures were sutured to the cervical stump or the vaginal stump (depending on the presence of the uterus or cervix), and they were fixed on the left and right sides of the sacral vertebra at the prevertebral fascia (at the level of S1/S2) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Half-sagittal view of bilateral uterosacral ligament (USL) replacement in the small pelvis. One part of the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) structure was sutured to the cervix. The parts of the PVDF structure (Dynamesh CESA; FEG Textiltechnik mbH, Aachen, Germany) that replaced the USL (arrows) had a length of 8.8 cm. They were sutured at the cervix, placed below the peritoneal fold of the USL on the left and right side of the prevertebral fascia in front of S1/S2 and were sutured at the sacrum.

The groups were compared using a nonparametric test, with the significance level set at p<0.05. As mentioned previously, 120 patients were randomised to the standard or control arm. Because of the premature termination of this study after the randomisation of 96 patients, the significance level was set at 0.0244 according to the O´Brien-Fleming alpha-spending function. Data were analysed using the intention-to-treat method. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 23 (IBM Corp. in Armonk, NY, USA), and ADDPLAN 6.0 (ICON plc., Dublin, Ireland).

Results

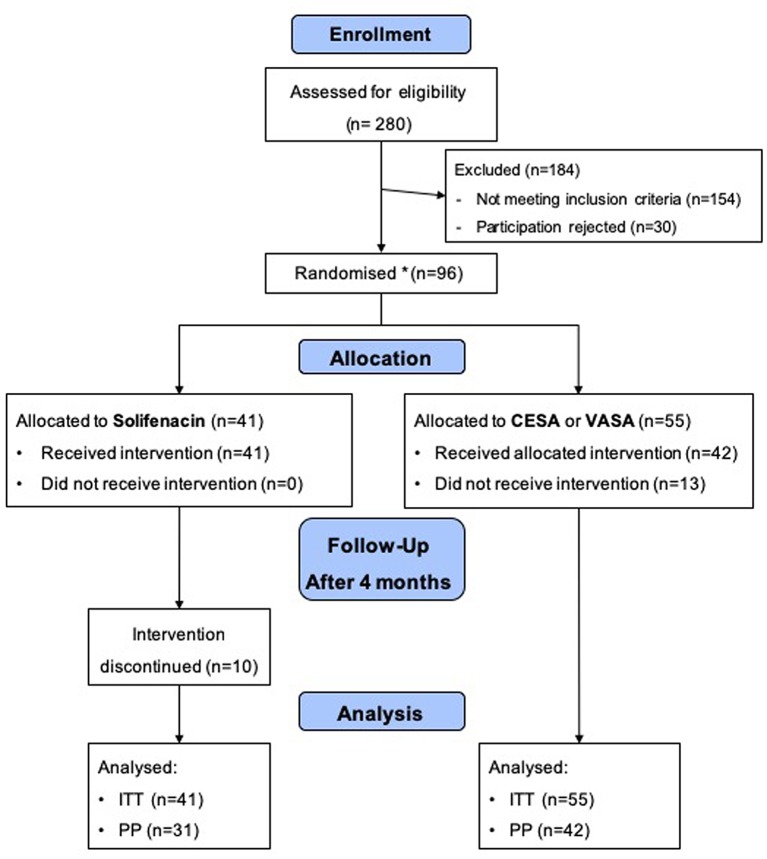

In total, 280 women with UUI or MUI presented to our Department between November 2012 and June 2016. Most of these patients underwent pre-treatment (anti-incontinence surgery or prolapse surgery) and were not eligible for participation. A total of 96 patients met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. Finally, 55 patients were randomised to the surgical treatment arm (CESA or VASA surgery) and 41 patients to the pharmacological treatment arm (solifenacin), respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flowchart of the URGE 1 study. CESA, Cervicosacropexy; VASA, vaginosacropexy; ITT: intention to treat; PP: per protocol. The study was terminated earlier to avoid a treatment bias between open abdominal and laparoscopic CESA and VASA surgery.

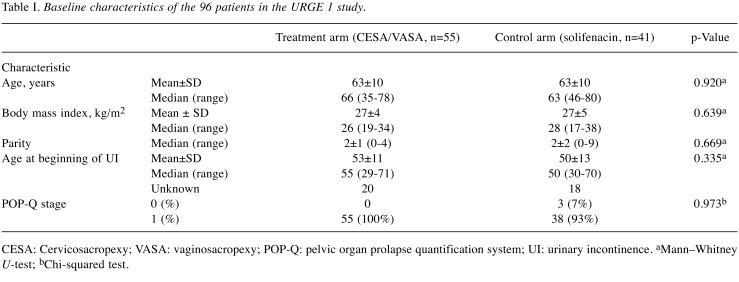

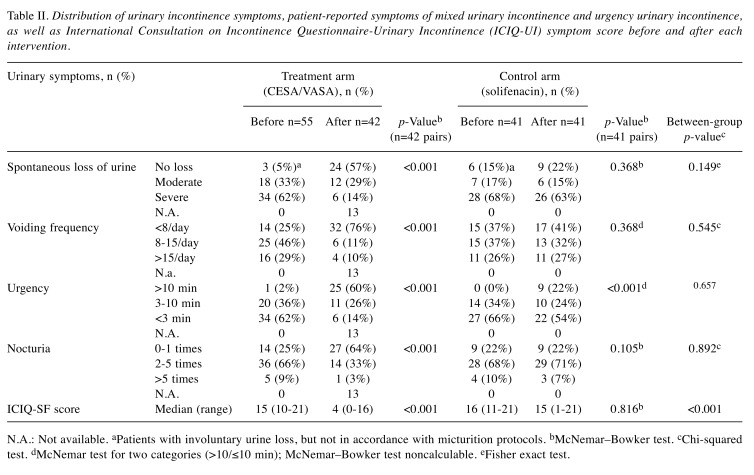

The baseline clinical parameters and UI symptoms before interventions were not statistically different between the surgical and pharmacological arms (Table I and Table II).

Table I. Baseline characteristics of the 96 patients in the URGE 1 study.

CESA: Cervicosacropexy; VASA: vaginosacropexy; POP-Q: pelvic organ prolapse quantification system; UI: urinary incontinence. aMann–Whitney U-test; bChi-squared test.

Table II. Distribution of urinary incontinence symptoms, patient-reported symptoms of mixed urinary incontinence and urgency urinary incontinence, as well as International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence (ICIQ-UI) symptom score before and after each intervention.

N.A.: Not available. aPatients with involuntary urine loss, but not in accordance with micturition protocols. bMcNemar–Bowker test. cChi-squared test. dMcNemar test for two categories (>10/≤10 min); McNemar–Bowker test noncalculable. eFisher exact test.

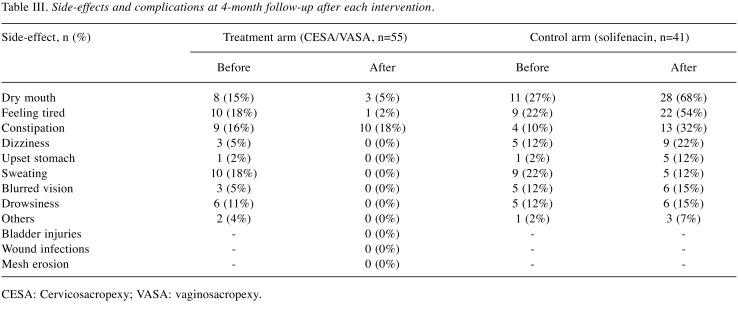

Moreover, 23 of the randomised 96 patients were considered drop outs: 13 patients in the surgical arm did not undergo intervention, and 10 patients discontinued solifenacin treatment within the first 4 weeks (Figure 2). None of the 13 patients in the surgical arm underwent surgery due to different reasons, such as other intermittent diseases or the demand for laparoscopic CESA or VASA. Patients in the pharmacological arm discontinued solifenacin treatment because of the lack of effects on incontinence or the development of side-effects (Table III.

Table III. Side-effects and complications at 4-month follow-up after each intervention.

CESA: Cervicosacropexy; VASA: vaginosacropexy.

Intraoperatively, one patient had severe bleeding, which was managed conservatively (vessel compression). No severe bladder or ureteral lesions were noted. No mesh erosions occurred during follow-up.

After CESA and VASA, there was a significant reduction in the number of patients with UI and a significant difference in ICIQ-SF scores (Table II). The status of the patients was classified as ‘continent’ if there were no symptoms postoperatively.

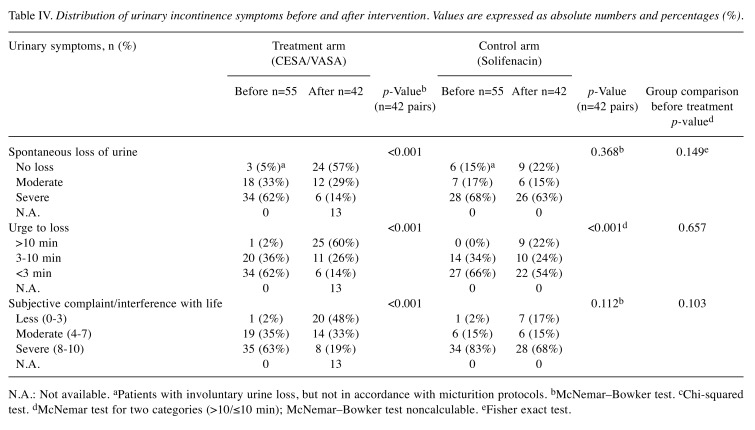

In 23 of the 55 patients in the surgical arm, CESA or VASA surgery resulted in the re-establishment of continence [42%, 95% confidence interval (CI)=29-55%]. These patients reported no more episodes of spontaneous urine loss and no loss of urine when they felt the first urge to urinate. Moreover, four out of the 41 patients in the pharmacological arm reported a continent status under solifenacin treatment (10%, 95% CI=1-19%). Their main UI symptom before solifenacin treatment was an increased daytime voiding frequency of 10 or more voids. According to the completed questionnaires, these four patients described their ability to ‘hold urine’ as ‘If I go immediately, I reach the toilet without losing urine’, which was categorised as loss of urine within 10 min (Table IV). The difference in the outcomes (before and after treatment) between the two intervention arms was highly significant (p=0.0006). Per-protocol analysis revealed that the difference remained significant. The results showed that this difference was 55% (95% CI=40-70%) after CESA or VASA and only 13% (95% CI=1-25%) during solifenacin treatment (p=0.0003) (Table IV).

Table IV. Distribution of urinary incontinence symptoms before and after intervention. Values are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages (%).

N.A.: Not available. aPatients with involuntary urine loss, but not in accordance with micturition protocols. bMcNemar–Bowker test. cChi-squared test. dMcNemar test for two categories (>10/≤10 min); McNemar–Bowker test noncalculable. eFisher exact test.

Regarding MUI, 15 out of the 55 patients with MUI became continent again after CESA or VASA surgery (27%, 95% CI=16-39%). Their UUI as well as SUI symptoms disappeared completely. During solifenacin treatment, only one patient with MUI reported continence (2%, 95% CI=0-7%). Even after adjusting the acceptable significance level to 0.0244, significant differences were found between the two intervention arms (p=0.0012). According to the per-protocol analysis, the success rate in the surgical and pharmacological arms was 36% (95% CI=21-50%) and 3% (95% CI=0-9%; p=0.0009), respectively. The distribution of UI symptoms before and after each intervention is listed in Table IV. The difference in preoperative and postoperative UI symptoms was only significant for the surgical arm. Neither the UI symptoms, age at surgery, or parity significantly influenced the cure rate in the surgical treatment arm.

Discussion

This study was based on the hypothesis that the ‘tension’ of the anterior vaginal wall is of importance for urinary continence (6-8). It was assumed that reducing the apical tension, defined as the lowering of the uterus (cervix) or vaginal vault, would lead to the expansion of the bladder base and, thereby, alleviation of irritation of the bladder’s stretch receptors. It is assumed that this ‘stretching’ results in urgency and UUI (27).

Current treatment options for UUI focus on the ‘chemical or peripheral denervation’ of these bladder receptors (27). These treatments options, however, mainly lead to a reduction of incontinence episodes, thereby indicating the importance of some other factors in urinary continence.

Based on the assumption that the bony dimensions of the small pelvis do not differ significantly among women, a comprehensible surgical technique (bilateral apical fixation) to replace the USL was developed (13). To compare the effects of this surgical stabilisation of the bladder base/upper vaginal third (surgical treatment option), this surgical technique was randomised against a pharmacological treatment (according to the current neurological hypothesis).

The results of this study demonstrated that the bilateral apical fixation of the apical vagina led to urinary continence in 42% of the patients. The effects of anticholinergic treatment, however, were limited to an improvement in urinary symptoms, which was occasionally interpreted as continence in 10% of the patients. This difference was highly significant, favouring CESA and VASA, and this led to the early termination of the study after 96 randomised patients (80% of the calculated number of patients).

However, before further conclusions can be drawn, the following aspects and limitations of the study warrant further discussion. From the methodological point of view, two aspects need to be discussed: the number of patients actually treated and the final assessment of symptoms.

In order to detect a 10% difference between the treatment and control arms, we had planned to randomise 120 patients. Due to the early termination of the study, the randomisation list was not fully processed, which resulted in an imbalance in the treatment arms. Therefore, we adjusted the significance level. Since the p-values arising from the analysis were below this adjusted level, early evaluation (termination) and assessment seemed justified.

The different reasons for drop outs in both study arms may be a reason for a bias. However, the patients who discontinued pharmacological therapy would probably have to be considered as nonresponders. On the other hand, the patients randomised to the surgical treatment arm but who preferred laparoscopy instead of laparotomy should not be considered as cases of surgical treatment failure. This would have led to even greater differences in cure and continence rates. This study was terminated earlier in order to avoid a treatment bias between the open abdominal and laparoscopic CESA/VASA surgery.

Furthermore, the assessment of clinical outcomes was based on the patients’ subjective complaints. ‘Placebo effects’ have been reported, especially in pharmacological studies evaluating the treatment of UI (28). As an example, a decrease in the number of UI episodes of one or two per day has been reported under anticholinergics, but this decrease has also been reported under placebo (1,29). In studies with surgical treatment, patients’ expectations are even higher, and their subjective treatment outcomes may be more positive than those judged by an objective observer. This possibility cannot be ruled out but a deliberate misjudgement of the patients’ treatments would not have been in their interest, because of further treatment options, either pharmacological treatment or TOT.

We would have liked to use objective measurement parameters but studies have shown that the results of urodynamic measurements do not correspond to clinical findings (30,31). For example, detrusor overactivity can be found as frequently in continent patients as well as in incontinent patients. Our urodynamic studies did not reveal a suitable parameter for the objectification of therapeutic success (22). For these reasons, we abstained from urodynamic examination and relied on the subjective complaints of the patients.

CESA and VASA surgeries corrected the genital prolapse (postoperative POP-Q stage 0) (12,20,22). It was difficult to understand and believe that apical fixation of the vagina re-established continence in patients with UUI, especially those with a ‘minor’ prolapse (POP-Q stage 1). The gynaecologist’s determination of a genital prolapse is based on the clinical examination of patients with an empty bladder on the gynaecological examination chair. However, most patients are not incontinent in the supine position (with an empty bladder) but only in the upright body position (with a filled bladder). Therefore, we decided to perform all gynaecological examinations additionally in the upright body position (standing) with a not-emptied bladder. The differences between the examinations on the examination chair and in the standing position were sometimes so striking that women with POP-Q stage 0 had the lowest point of the bladder (POP-Q point Ba) at +1 cm (POP-Q stage 2) in the upright body position. In that respect, all patients in the study had a ‘masked’ prolapse. If POP-Q stage 0 is defined as the normal physiological position, it must be concluded that the apical holding apparatus was defective in all our patients with UUI.

The results were surprising, as we only expected an improvement in UUI symptoms after CESA or VASA. In the patients with MUI, we assumed that these patients needed a TOT to support the urethra (21). In principle, apical stabilisation (CESA or VASA) should be able to effectively treat both forms of UI. This can be explained by the ‘elevating effect’ after bilateral USL replacement, which also affects the lower third of the vagina. In this context, an additional repair of level 3 by TOT was found to lead to urinary continence in approximately 75% of patients with MUI and UUI (21,32). However, we also observed that UUI symptoms only disappeared when a TOT was inserted after apical fixation (e.g. CESA or VASA surgery) (own observation). One must assume that the stabilisation of the anterior vaginal wall depends critically on apical suspension. The correction of this suspension alone can lead to continence.

From the anatomical point of view, both CESA and VASA elevate the apical vaginal end and lead to stabilisation of the urethral-vesical junction. From previous studies, we knew that this elevation must be bilateral to establish urinary continence in these patients (12,21,22,33,34). How that leads to continence remains a matter of speculation. It can be speculated that the bilateral elevation of the bladder base directs the vertical vector of a filled bladder from the posterior part of the bladder to the more anterior parts. Therefore, the pressure on the stretch receptors at the bladder base is diminished, as is the pressure on the urethral entrance to the bladder.

Considering that several studies have reported a cure for UI after anterior colporrhaphy, one can assume that the anatomical correction in level 2 will further contribute to regain urinary continence (10,35,36).

Conclusion

The findings of this study strongly indicate that re-establishing pelvic floor anatomy can lead to restoration of urinary continence, and the results indicate the importance of the anterior compartment for MUI and UUI.

Bilateral USL replacement (according to the CESA or VASA surgical technique) was performed in a standardised and comprehensible manner—with a minimum amount of material and structures of defined size, shape, and lengths at defined fixation sites. This standardisation allows for good comparability of clinical outcomes among further studies.

Conflicts of Interest

W. Jäger and S. Ludwig received travel bursaries from FEG Textiltechnik mbH Company (Aachen, Germany). I. Becker and P. Mallmann declare that they have no conflicts of interest in regard to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

SL: manuscript writing, project development, and data collection. IB: statistical analysis. PM: project development, manuscript writing. WJ: project development, manuscript writing, and data collection.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Mrs. Jessica Schmidt and Mrs. Zook-Nym Hess for their efforts in the outpatient ward. Our special thanks go to Mrs. Elke Neumann for her continuous help in data monitoring and maintaining contact with the study patients; she was always willing to listen to patients’ needs and problems.

References

- 1.Alhasso AA, McKinlay J, Patrick K, Stewart L. Anticholinergic drugs versus non-drug active therapies for overactive bladder syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD003193. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003193.pub3. PMID: 17054163. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003193.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson KE, Chapple CR, Cardozo L, Cruz F, Hashim H, Michel MC, Tannenbaum C, Wein AJ. Pharmacological treatment of overactive bladder: Report from the international consultation on incontinence. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19(4):380–394. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32832ce8a4. PMID: 19448545. DOI: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32832ce8a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steers WD. Pathophysiology of overactive bladder and urge urinary incontinence. Rev Urol. 2002;4 (Suppl 4):S7–S18. PMID: 16986023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anger JT, Weinberg A, Suttorp MJ, Litwin MS, Shekelle PG. Outcomes of intravesical botulinum toxin for idiopathic overactive bladder symptoms: A systematic review of the literature. J Urol. 2010;183(6):2258–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.009. PMID: 20400142. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasavada PS, Rackley RR. Electrical stimulation in storage and emptying failure. In: Campbell-Walsh Urology 10th edition. Wein AJ KL, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW and Peters CA (eds.) Elsevier Health Science Inc. Philadelphia. 2011:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLancey JO. Structural support of the urethra as it relates to stress urinary incontinence: The hammock hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(6):1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70346-9. discussion 1720-1713 PMID: 8203431. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petros PE, Ulmsten UI. An integral theory of female urinary incontinence. Experimental and clinical considerations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1990;153:7–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.1990.tb08027.x. PMID: 2093278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulmsten U, Petros P. Surgery for female urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;4(3):456–462. PMID: 1623156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLancey JO. The anatomy of the pelvic floor. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;6(4):313–316. PMID: 7742491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boer TA, Salvatore S, Cardozo L, Chapple C, Kelleher C, van Kerrebroeck P, Kirby MG, Koelbl H, Espuna-Pons M, Milsom I, Tubaro A, Wagg A, Vierhout ME. Pelvic organ prolapse and overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):30–39. doi: 10.1002/nau.20858. PMID: 20025017. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen JK, Bhatia NN. Resolution of motor urge incontinence after surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse. J Urol. 2001;166(6):2263–2266. PMID: 11696748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager W, Mirenska O, Brugge S. Surgical treatment of mixed and urge urinary incontinence in women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;74(2):157–164. doi: 10.1159/000339972. PMID: 22890409. DOI: 10.1159/000339972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizk DE, Czechowski J, Ekelund L. Dynamic assessment of pelvic floor and bony pelvis morphologic condition with the use of magnetic resonance imaging in a multiethnic, nulliparous, and healthy female population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.041. PMID: 15295346. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delorme E. Transobturator urethral suspension: Mini-invasive procedure in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women. Prog Urol. 2001;11(6):1306–1313. PMID: 11859672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulmsten U. An introduction to tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) – a new surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S3–S4. doi: 10.1007/pl00014599. PMID: 11450978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford AA, Rogerson L, Cody JD, Ogah J. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD006375–CD006375. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub3. PMID: 26130017. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petros PE, Ulmsten U. Bladder instability in women: A premature activation of the micturition reflex. Neurourol Urodyn. 1993;12(3):235–239. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930120305. PMID: 8330046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jäger W. Vagino-sacropexy (VASA) and vagino-recto-sacropexy (VARESA). In: Alkatout I and Mettler l, (eds). Hysterectomy - A Comprehensive Surgical Approach. Cham, Springer International Publishing. Switzerland. 2016:1137–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jäger W. Cham, Springer International Publishing. Switzerland. 2016. Cervico-sacropexy (CESA) and cervico-recto-sacropexy (CERESA). In: Hysterectomy – A Comprehensive Surgical Approach. Alkatout I and Mettler l (eds) pp. 1117–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager W, Ludwig S, Stumm M, Mallmann P. Standardized bilateral mesh supported uterosacral ligament replacement - cervicosacropexy (CESA) and vagino-sacropexy (VASA) operations for female genital prolapse. Pelviperineology. 2016;35(1) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludwig S, Stumm M, Neumann E, Becker I, Jäger W. Surgical treatment of urgency urinary incontinence, OAB (WET), mixed urinary incontinence, and total incontinence by cervicosacropexy or vaginosacropexy. Gynecol Obstet. 2016;6:404–404. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0932.1000404. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajshekhar S, Mukhopadhyay S, Morris E. Early safety and efficacy outcomes of a novel technique of sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of apical prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;135(2):182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.05.007. PMID: 27498595. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, Shull BL, Smith AR. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. PMID: 8694033. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(4):322–330. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. PMID: 15227649. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardozo L, Coyne KS, Versi E. Validation of the urgency perception scale. BJU Int. 2005;95(4):591–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05345.x. PMID: 15705086. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homma Y, Koyama N. Minimal clinically important change in urinary incontinence detected by a quality of life assessment tool in overactive bladder syndrome with urge incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(3):228–235. doi: 10.1002/nau.20195. PMID: 16532466. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, Cartwright R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17097. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.97. PMID: 28681849. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyle K, Batzer FR. Is a placebo-controlled surgical trial an oxymoron. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(3):278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.12.006. PMID: 17478356. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herschorn S, Chapple CR, Abrams P, Arlandis S, Mitcheson D, Lee KS, Ridder A, Stoelzel M, Paireddy A, van Maanen R, Robinson D. Efficacy and safety of combinations of mirabegron and solifenacin compared with monotherapy and placebo in patients with overactive bladder (synergy study) BJU Int. 2017;120(4):562–575. doi: 10.1111/bju.13882. PMID: 28418102. DOI: 10.1111/bju.13882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caruso DJ, Kanagarajah P, Cohen BL, Ayyathurai R, Gomez C, Gousse AE. What is the predictive value of urodynamics to reproduce clinical findings of urinary frequency, urge urinary incontinence, and/or stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(10):1205–1209. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1180-7. PMID: 20559620. DOI: 10.1007/s00192-010-1180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haddad JM, Monaco HE, Kwon C, Bernardo WM, Guidi HG, Baracat EC. Predictive value of clinical history compared with urodynamic study in 1,179 women. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2016;62(1):54–58. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.62.01.54. PMID: 27008494. DOI: 10.1590/1806-9282.62.01.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig S, Stumm M, Mallmann P, Jager W. TOT 8/4: A way to standardize the surgical procedure of a transobturator tape. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2016/4941304. PMID: 26981532. DOI: 10.1155/2016/4941304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amundsen CL, Flynn BJ, Webster GD. Anatomical correction of vaginal vault prolapse by uterosacral ligament fixation in women who also require a pubovaginal sling. J Urol. 2003;169(5):1770–1774. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000061472.94183.26. PMID: 12686830. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000061472.94183.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barber MD, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL, Bump RC. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site-specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1402–1410. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.111298. discussion 1410-1401 PMID: 11120503. DOI: 10.1067/mob.2000.111298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basu M, Wise B, Duckett J. Urgency resolution following prolapse surgery: Is voiding important. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(8):1309–1313. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2010-x. PMID: 23232824. DOI: 10.1007/s00192-012-2010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fayyad AM, Redhead E, Awan N, Kyrgiou M, Prashar S, Hill SR. Symptomatic and quality of life outcomes after site-specific fascial reattachment for pelvic organ prolapse repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(2):191–197. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0424-7. PMID: 17874216. DOI: 10.1007/s00192-007-0424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]