Abstract

Objective:

The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) is used worldwide to assess three styles (authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive) and seven dimensions of parenting. In this study, we adapted the short version of the PSDQ for use in Brazil and investigated its validity and reliability.

Methods:

Participants were 451 mothers of children aged 3 to 18 years, though sample size varied with analyses. The translation and adaptation of the PSDQ followed a rigorous methodological approach. Then, we investigated the content, criterion, and construct validity of the adapted instrument.

Results:

The scale content validity index (S-CVI) was considered adequate (0.97). There was evidence of internal validity, with the PSDQ dimensions showing strong correlations with their higher-order parenting styles. Confirmatory factor analysis endorsed the three-factor, second-order solution (i.e., three styles consisting of seven dimensions). The PSDQ showed convergent validity with the validated Brazilian version of the Parenting Styles Inventory (Inventário de Estilos Parentais – IEP), as well as external validity, as it was associated with several instruments measuring sociodemographic and behavioral/emotional-problem variables.

Conclusion:

The PSDQ is an effective and reliable psychometric instrument to assess childrearing strategies according to Baumrind’s model of parenting styles.

Keywords: Child psychiatry, tests/interviews – psychometric, other psychological issue, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, psychotherapy

Introduction

Parenting – the way parents deal with rules, behavior, and affection of their children – can influence the course of the child’s emotional, psychosocial, and behavioral development.1 Parenting behaviors are classically categorized into two dimensions: one of parental control (e.g., discipline, monitoring, and autonomy-granting) and the other of affection toward the child (e.g., warmth, acceptance, and responsiveness).2 The extent to which parents demonstrate behaviors in each of these two parenting dimensions is used to classify their parenting style as authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive.3 Parents who predominantly display control behaviors and less affection are categorized as authoritarian; parents who show both control and affection are defined as authoritative or democratic; and parents who use behavioral strategies focused on affection and very few on parental control are categorized as permissive.2,3

Parenting styles correlate with children’s psychosocial outcomes, with the authoritative/democratic style being most correlated with advantageous outcomes.3-5 The authoritarian style has been found to correlate with higher levels of anxiety and depression, poor emotional control, and oppositional defiant behaviors in children.4,6 The role of the permissive style in children’s outcomes is more controversial than those related to the other parenting styles. Although child and parental characteristics are also involved, the permissive style is thought to increase internalizing disorders,7 and children with permissive parents are more likely to have deficits in self-control abilities.8 Altogether, the reasons for studying parenting itself and considering parenting when investigating child development and health outcomes are overwhelming.

The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ)9,10 was developed to measure parenting within the typologies and definitions described by Baumrind et al.3,4 The instrument is used worldwide for the measurement of several parenting aspects as well as broader parenting styles.11 The original version of the instrument showed good reliability and validity,10 but several studies use selected items of the questionnaire or shortened versions.11 In a review of the reliability and validity of the PSDQ, the authors suggested that cross-cultural comparisons and more in-depth psychometric analyses were needed.11

The theoretical background on parenting is not as solid, with some parenting styles defined as consisting of two dimensions12 and others consisting of 18 dimensions.13 Some studies contemplate four types of parenting styles, defined as the interaction of acceptance and strictness dimensions, but do not cite this as Baumrind’s typology.14,15

In Brazil, research on parenting styles is still incipient when compared to other countries. Some instruments designed to assess parenting have been adapted for the Brazilian population, but their methodological limitations are noteworthy. First, most of the instruments available were not based on Baumrind’s theory, which has the strongest empirical foundation.16 Two studies with Brazilian populations investigated parenting styles according with Baumrind’s two-dimensions model, but the instruments used were only translated for Brazilian Portuguese, not cross-culturally adapted, and were not originally based on Baumrind’s model.14,15 One instrument was based on the two dimensions of Baumrind’s model,17 but the questionnaire was for adolescents only. Also, the psychometric properties of the Brazilian instruments are not always satisfactory,18 and the age range investigated has been fairly broad: 6 to 10 years,19 10 to 18 years,20 adolescence,12,21 and 14 to 69 years.13

In this study, we aimed to translate and adapt the self-report, short-form (32-item) version of the PSDQ10,22 to the Brazilian context and investigate its reliability and validity for use in Brazil.

Methods

Ethics

The present study was approved by the institutional review board of the Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil (CAAE: 57376016.8.0000.5134).

Participants

The sample consisted of 451 mothers of children aged 3 to 18 years, recruited from local schools, the researcher’s social network, an online platform, and an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) clinic at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, Brazil. All participants consented to have their data used in this study. Participants consisted of mothers of children with ADHD (n=203) and of typically developing children (n=248). These groups did not differ regarding age (t 449 = 0.61, p = 0.540), education (t 449 = 1.30, p = 0.193), or socioeconomic status (t 449 = 1.33, p = 0.186). In multiple-child families, only one child was considered in this study. We collapsed data across all sets to increase statistical power. Considering the full sample and correlation methods, our sample had 0.99 power to detect large and moderate effects and 0.56 power to detect small effects.

The overall profile of mothers and children in the sample is described in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

| Mothers’ characteristics (n=451) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 38.44 (6.51) |

| Educational attainment (years), mean (SD) | 11.20 (4.55) |

| Household size, mean (SD) | 3.79 (1.05) |

| Origin of recruitment | |

| Local community (schools, social network) | 313 (69) |

| ADHD clinic | 111 (25) |

| Online platform | 27 (6) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 60/390 (15) |

| Married | 262/390 (67) |

| Divorced | 40/390 (10) |

| Widowed | 12/390 (3) |

| Cohabitating | 14/390 (4) |

| Other | 2/390 (< 1) |

| Economic class* | |

| B2 (1,387.89) | 10 (2) |

| C1 (755.18) | 419 (93) |

| C2 (453.37) | 5 (1) |

| D-E (200.56) | 17 (4) |

| Children’s characteristics (n=451) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 8.69 (2.84) |

| Educational attainment (years), mean (SD) | 3.47 (2.58) |

| Male gender | 274/451 (61) |

| ADHD | 203/451 (45) |

| Typically developing | 248/451 (55) |

| Type of school | |

| Public | 247/430 (57) |

| Private | 183/430 (43) |

| Lives with | |

| Both parents | 248/311 (80) |

| Mother alone | 63/311 (20) |

Data presented as n (%) and n/N (%), unless otherwise specified. N varies due to missing data.

ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SD = standard deviation.

According to the Brazilian Economic Classification Criterion.22 Average household income in U.S. dollars presented in parenthesis.

Participants’ assessment

Parenting Style and Dimension Questionnaire – Short Version (PSDQ)

The Short Version of the PSDQ consists of 32 items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). On each item, the parent must inform the frequency with which he or she uses the specific behavior described. The 32 items can be grouped into three styles and seven dimensions of parenting.23 The authoritative parenting style includes 15 items, which are divided into three dimensions: support and affection, regulation, and autonomy. The authoritarian style has 12 items and consists of three dimensions: physical coercion, verbal hostility, and punishment. The permissive style consists of one dimension, indulgence, which is composed of five items. The parenting dimensions are calculated as the arithmetic mean of the scale items, and the parenting styles are the arithmetic mean of its dimensions. Therefore, the score in all dimensions and styles ranges from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more use of its dimensions or styles.

Parenting Styles Inventory (Inventário de Estilos Parentais – IEP)

The IEP is an inventory created to assess techniques and strategies used by parents to raise their children.21 The instrument consists of 42 items distributed equally across seven educational practices: A) positive monitoring; B) moral behavior; C) inconsistent punishment; D) negligence; E) lax discipline; F) negative monitoring; and G) physical abuse. The instrument can be administered to parents (answering about themselves) or to adolescents (rating their parents’ behavior). Respondents indicate the frequency of each practice on a three-point scale: never = 0; sometimes = 1; and always = 2. The sum of scores yields educational practice indices.

Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria

The Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria (Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil – CCEB) assigns weighted points to household data (presence and number of appliances and facilities, educational attainment of the head of household) to generate a score that categorizes households into one of six economic classes: A, B1, B2, C1, C2, and D-E.22

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham – Version IV (SNAP-IV)

Parents completed the Brazilian version of the SNAP-IV, a 26-item questionnaire corresponding to criterion A of the DSM-IV for ADHD and for symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).24 Parents rate inattentive, hyperactive, impulsive, and defiant behaviors of their children using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). In this study, we used the scores for inattentive symptoms (which consists of the sum of ratings of nine items), hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (also consisting of the sum of ratings of nine items), oppositional defiant symptoms (the sum of ratings of eight items), and an ADHD score, which consists of the sum of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive scores.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

Parents completed this form, which gathers information about a child’s behavioral and emotional problems.25 The CBCL is composed of 113 items, and parents rate their child’s behavior on a three-point Likert scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). In this study, we used the t-scores for internalizing problems (emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints, withdrawn, and sleep problems) and externalizing behavior (attention problems, aggressive behavior, rule-breaking, and aggressive behavior), corrected for age and gender (mean = 50, standard deviation = 10).

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

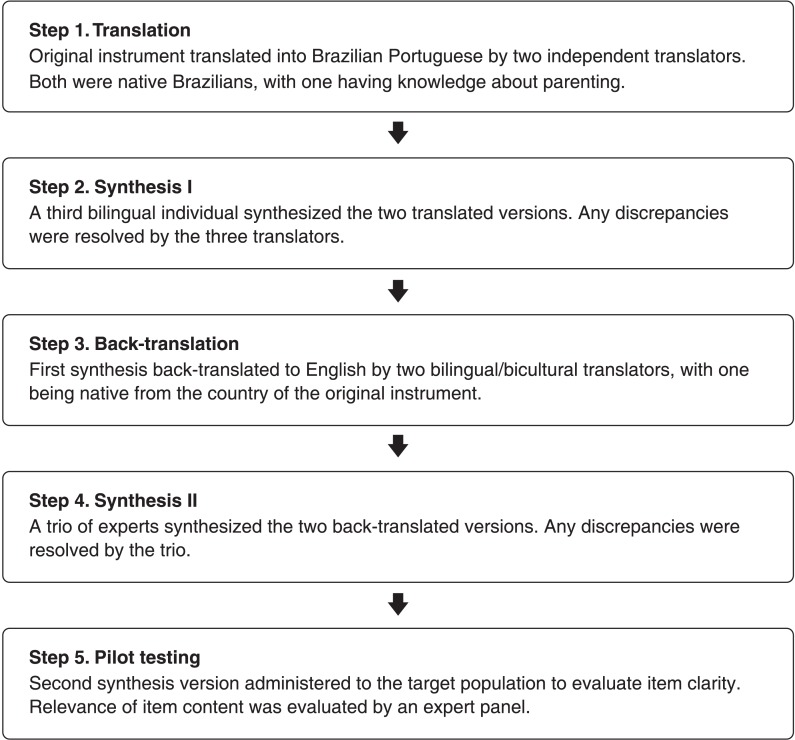

The translation and adaptation of the PSDQ were conducted as a five-step process, following the methodological approach summarized by Sousa & Rojjanasrirat,26 as seen in Figure 1. Briefly, the first step was the development of two independent translations of the original instrument to Brazilian Portuguese. In the second step, a third bilingual individual compared the translated versions for ambiguity and discrepancy of words, sentences, and meanings. Discrepancies were then resolved by all translators, who agreed on a first synthesis version. This version was then independently back-translated to English by two other bilingual/bicultural translators. The fourth step was the comparison of the two back-translated versions to the original version by a trio of experts with extensive clinical experience in psychology, who analyzed format, wording, grammatical structure, similarity in meaning, and relevance. No item had to go through the previous steps again, and a pre-final version of the PSDQ in Brazilian Portuguese was approved.

Figure 1. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation process (according to Sousa & Rojjanasrirat26).

For the fifth step, pilot testing, the pre-final version of the PSDQ was evaluated by 13 parents (age, 31 to 63 years; mean, 47.5±11.8; three fathers, 10 mothers). Parents had completed at least primary and secondary education (mean educational attainment, 12.4±2.7 years). Parents indicated whether the questionnaire items were clear using a dichotomous scale (i.e., clear vs. unclear). An item was deemed sufficiently clear for the target population when 80% of the pilot sample evaluated the item as clear.24 In our sample, six items were not evaluated as sufficiently clear (items 2, 3, 6, 16, 19, and 28). The translation and adaptation process was reapplied to those items until they met the clarity criteria.

Validity and reliability analysis

The preliminary final version was submitted to an expert panel of seven specialists, including two graduate researchers and five clinical psychologists, for determination of the concept and content equivalence of the items (content validity). Each member of the panel was asked to determine whether the instructions, response format, and items were clear. Then, the expert panel classified each item on its relevance, using the following scale: 1 = not relevant; 2 = little relevant; 3 = relevant; 4 = extremely relevant. After scoring, a content validity index (CVI) was generated for each item and for the overall scale (S-CVI).

Due to the ordinal nature of the scale (e.g., a Likert-type scale of fewer than seven points), we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the weighted least squares means and variance (WLSMV) estimator. Four theoretical models of the PSDQ, previously described for the population of Portugal by Pedro et al.,27 were analyzed through CFA to ascertain whether they fit this sample, considering Brazil’s national conditions and cultural background. A range of indices was used to assess how well the data fit the proposed model: the chi-square value and corresponding p-value, the relative chi-square statistic; the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); the comparative fit index (CFI); and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). In our sample, the subject-to-item ratio was 14/1.

To investigate convergent validity, we tested for correlation between raw data on the PSDQ styles and the seven parental educational practices of the Brazilian IEP. This procedure was conducted in a smaller maternal subsample (n=19). Due to the small sample size, correlations were performed by using a resampling strategy (bootstrapping, k = 5,000). We also analyzed the correlation of the Brazilian version of the PSDQ with sociodemographic variables (child’s age and gender, mother’s age, and educational attainment), family’s socioeconomic status, and children’s behavioral problems.

To analyze the reliability of the PSDQ, we assessed both internal consistency (McDonald’s omega) and test-retest stability with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), by the two-way mixed model. Test-retest reliability was assessed by comparing two reports of 15 parents, obtained with a mean interval of 5.64±4.35 weeks. Data were analyzed in SPSS version 20, Mplus version 6.12, and JASP version 0.8.1.1.

Results

Table 2 presents the original items and their final translation and cross-cultural adaptation for the Brazilian population. Table 2 also lists item CVIs and the overall S-CVI, with almost all items showing adequate evidence for content validity. The CVI was higher than 0.80 for all items, except for item 24 (“I spoil our child”), which had a CVI of 0.71. The S-CVI was 0.97.

Table 2. Original version of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – Short Version (PSDQ) and its adaptation for the Brazilian context, with CVIs.

| Item | Original version | Brazilian version | CVI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I am responsive to our child’s feelings or needs. | Eu respondo aos sentimentos ou necessidades do(a) meu (minha) filho(a). | 1.00 |

| 2 | I use physical punishment as a way of disciplining our child. | Eu uso castigos físicos como forma de disciplinar meu (minha) filho(a). | 1.00 |

| 3 | I take our child’s desires into account before asking the child to do something. | Eu levo em conta a vontade do(a) meu (minha) filho(a) antes de lhe pedir para fazer alguma coisa. | 1.00 |

| 4 | When our child asks why (he)(she) has to conform, I state: because I said so or I am your parent and I want you to. | Quando meu (minha) filho(a) pergunta por que tem que obedecer, eu digo: “Porque eu disse que sim” ou “Porque eu sou seu (sua) pai/mãe e eu quero assim”. | 1.00 |

| 5 | I explain to our child how we feel about the child’s good and bad behavior. | Eu explico ao(à) meu (minha) filho(a) como me sinto em relação ao seu bom e ao seu mau comportamento. | 1.00 |

| 6 | I spank when our child is disobedient. | Quando meu (minha) filho(a) é desobediente, eu dou uma palmada nele(a). | 1.00 |

| 7 | I encourage our child to talk about the child’s troubles. | Eu encorajo meu (minha) filho(a) a conversar sobre seus problemas. | 1.00 |

| 8 | I find it difficult to discipline our child. | Eu acho difícil disciplinar meu (minha) filho(a). | 1.00 |

| 9 | I encourage our child to freely express (himself)(herself) even when disagreeing with parents. | Eu encorajo meu (minha) filho(a) a se expressar abertamente, mesmo quando eu não concordo com ele(a). | 1.00 |

| 10 | I punish by taking privileges away from our child with little if any explanations. | Eu castigo meu (minha) filho(a) lhe tirando privilégios com pouca ou nenhuma explicação. | 1.00 |

| 11 | I emphasize the reasons for rules. | Eu explico os motivos para as regras. | 1.00 |

| 12 | I give comfort and understanding when our child is upset. | Eu dou conforto e compreensão ao(à) meu (minha) filho(a) quando ele(a) está chateado(a). | 1.00 |

| 13 | I yell or shout when our child misbehaves. | Eu grito ou berro quando meu (minha) filho(a) se comporta mal. | 1.00 |

| 14 | I give praise when our child is good. | Eu parabenizo meu (minha) filho(a) quando ele(a) se comporta bem. | 1.00 |

| 15 | I give into our child when the child causes a commotion about something. | Eu acabo cedendo quando meu (minha) filho(a) faz birra por alguma coisa. | 1.00 |

| 16 | I explode in anger towards our child. | Eu tenho explosões de raiva com meu (minha) filho(a). | 1.00 |

| 17 | I threaten our child with punishment more often than actually giving it. | Eu ameaço castigar meu (minha) filho(a) mais vezes do que realmente o(a) castigo. | 1.00 |

| 18 | I take into account our child’s preferences in making plans for the family. | Eu levo em consideração as preferências do(a) meu (minha) filho(a) ao fazer planos para a família. | 1.00 |

| 19 | I grab our child when he/she is being disobedient. | Eu seguro com força meu (minha) filho(a) quando ele(a) é desobediente. | 0.86 |

| 20 | I state punishments to our child and do not actually do them. | Eu determino castigos para meu (minha) filho(a), mas não os cumpro realmente. | 1.00 |

| 21 | I show respect for our child’s opinions by encouraging our child to express them. | Eu mostro respeito pelas opiniões do(a) meu (minha) filho(a) lhe encorajando a expressá-las. | 1.00 |

| 22 | I allow our child to give input into family rules. | Eu permito que meu (minha) filho(a) dê opiniões nas regras da família. | 1.00 |

| 23 | I scold and criticize to make our child improve. | Eu repreendo e critico duramente meu (minha) filho(a) para fazê-lo(a) melhorar. | 1.00 |

| 24 | I spoil our child. | Eu mimo meu (minha) filho(a). | 0.71 |

| 25 | I give our child reasons why rules should be obeyed. | Eu explico ao(à) meu (minha) filho(a) as razões pelas quais as regras devem ser obedecidas. | 1.00 |

| 26 | I use threats as punishment with little or no justification. | Eu uso ameaças como forma de castigo com pouca ou nenhuma justificativa. | 0.86 |

| 27 | I have warm and intimate times together with our child. | Eu tenho momentos calorosos e especiais com o(a) meu (minha) filho(a). | 1.00 |

| 28 | I punish by putting our child off somewhere alone with little if any explanations. | Como uma forma de castigo, eu coloco meu (minha) filho(a) em algum lugar sozinho(a), mas sem dar muita explicação. | 1.00 |

| 29 | I help our child to understand the impact of behavior by encouraging our child to talk about the consequences of his/her own actions. | Eu ajudo meu (minha) filho(a) a entender o impacto do seu comportamento lhe encorajando a falar sobre as consequências de suas ações. | 1.00 |

| 30 | I scold or criticize when our child’s behavior doesn’t meet our expectations. | Eu repreendo e critico duramente meu (minha) filho(a) quando seu comportamento não atinge minhas expectativas. | 1.00 |

| 31 | I explain the consequences of the child’s behavior. | Eu explico ao(à) meu (minha) filho(a) as consequências do seu comportamento. | 0.86 |

| 32 | I slap our child when the child misbehaves. | Eu dou uma palmada no(a) meu (minha) filho(a) quando ele(a) se comporta mal. | 0.86 |

| CVI | 0.97 |

CVI = content validity index.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which tests the overall significance of all correlations within the correlation matrix, was significant (χ2 496 = 4,685.127, p < 0.001), indicating that it the factor analytic model was appropriate for this set of data. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy indicated that the strength of the relationships among variables was high (KMO = 0.851). Thus, it was acceptable to proceed with the analysis. Widely adopted guidelines are available to gauge how well a model fits the data. Concerning the chi-square/degrees of freedom (df) index, a value of less than 2 indicates good fit. An RMSEA value of 0.08 or lower also indicates that a model can be considered adequate to fit the data. A CFI and TLI with values of 0.90 can be considered as adequately fitting the data. Each index of model fit is shown for the four models in Table 3: model 1 tested the original three-factor, second-order solution (i.e., three styles consisting of seven dimensions); model 2 tested a three first-order factors solution (i.e., three styles only); model 3 tested a two first-order factors solution (i.e., positive parenting vs. negative parenting); and model 4 tested a unidimensional first-order factor solution. Only model 1 was considered suitable in this study (Table 3).

Table 3. Fit indices for confirmatory factor analysis models.

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | - | 1,242.661* | 1,633.083* | 1,735.849* | 365.701* |

| df | - | 455 | 461 | 463 | 464 |

| χ2/df | < 3 | 2.73 | 3.54 | 3.75 | 7.87 |

| CFI | > 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.63 |

| TLI | > 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.61 |

| RMSEA | < 0.080 | 0.062 (0.058-0.066) | 0.075 (0.071-0.079) | 0.078 (0.074-0.082) | 0.123 (0.120-0.127) |

| Results | Suitable | Unsuitable | Unsuitable | Unsuitable |

Model 1 = three-factor, second-order solution; Model 2 = three first-order factors solution; Model 3 = two first-order factors solution; Model 4 = unidimensional first-order factor solution.

CFI = comparative fit index; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index.

p < 0.05.

Association between PSDQ styles and IEP

Correlations between PSDQ and IEP are shown in Table 4. We found that the PSDQ authoritative style was not associated with the educational practices measured by the IEP, not even the positive ones (i.e., positive monitoring and moral behavior). The PSDQ authoritarian style correlated with four of five negative parenting practices of the IEP. The PSDQ permissive style correlated negatively with the IEP moral behavior and negligence categories, and positively with lax discipline and physical abuse.

Table 4. PSDQ styles and their correlation with IEP educational practices.

| PSDQ styles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IEP styles | 1. Authoritative | 2. Authoritarian | 3. Permissive |

| Positive monitoring | 0.235 | -0.157 | -0.246 |

| Moral behavior | 0.071 | -0.378 | -0.657† |

| Inconsistent punishment | -0.088 | 0.461* | 0.223 |

| Negligence | -0.035 | -0.388 | -0.468* |

| Lax discipline | 0.194 | 0.821† | 0.789† |

| Negative monitoring | 0.326 | 0.511* | 0.384 |

| Physical abuse | 0.205 | 0.679† | 0.492* |

IEP = Inventário de Estilos Parentais (Parenting Styles Inventory); PSDQ = Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – Short Version.

Results are based on 5,000 bootstrap samples (n=19).

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Association of PSDQ styles and dimensions with sociodemographic variables and children’s behavioral/emotional problems

These results are shown in Table 5. Regarding demographic characteristics, we observed that maternal warmth and support tended to decrease while verbal hostility tended to increase with the child’s age. The authoritarian style and, mainly, the physical coercion dimension were negatively associated with maternal age. Maternal education was positively associated with authoritative parenting, but negatively associated with authoritarian parenting. Mothers with higher education showed higher warmth and support and regulation, as well as less physical coercion, verbal hostility, and punishment. The permissive parenting style was not associated with demographic characteristics. Additionally, family economic status was not associated with any parenting styles and dimensions in this sample, except for a weak positive association with the warmth and support dimension.

Table 5. PSDQ styles and dimensions and their correlation with sociodemographic variables, children’s behavioral/emotional problems, and reliability.

| PSDQ styles | PSDQ dimensions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | 1. Authoritative | 2. Authoritarian | 3. Permissive | 1A. Warmth and support | 1B. Regulation | 1C. Autonomy | 2A. Physical coercion | 2B. Verbal hostility | 2C. Punitive | 3A. Indulgent |

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Child’s age (n=451) | -0.090 | 0.030 | -0.030 | -0.145† | -0.030 | -0.030 | -0.102* | 0.111* | 0.020 | -0.030 |

| Mother’s age (n=427) | 0.050 | -0.120* | -0.020 | 0.020 | 0.030 | 0.060 | -0.120* | -0.103* | -0.070 | -0.020 |

| Mother’s educational attainment (n=424) | 0.133† | -0.154† | -0.080 | 0.129† | 0.113* | 0.070 | -0.161† | -0.090 | -0.155† | -0.080 |

| Socioeconomic score (CCEB) (n=451) | 0.060 | 0.030 | 0.010 | 0.097* | 0.060 | 0.030 | 0.070 | < 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.010 |

| Child’s behavioral/emotional problems | ||||||||||

| Inattention (SNAP-IV) (n=451) | -0.138† | 0.263† | 0.246† | -0.090 | -0.148† | -0.129† | 0.248† | 0.223† | 0.150† | 0.246† |

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity (SNAP-IV) (n=451) | -0.104* | 0.348† | 0.223† | -0.109* | -0.115* | -0.057 | 0.336† | 0.263† | 0.257† | 0.223† |

| ADHD symptoms (SNAP-IV) (n=451) | -0.132† | 0.341† | 0.263† | -0.105* | -0.138† | -0.106* | 0.320† | 0.280† | 0.220† | 0.263† |

| ODD symptoms (SNAP-IV) (n=451) | -0.138† | 0.361† | 0.268† | -0.142† | -0.133† | -0.094* | 0.344† | 0.264† | 0.297† | 0.268† |

| Internalizing score (CBCL) (n=325) | -0.114* | 0.219† | 0.217† | -0.154† | -0.101 | -0.039 | 0.124* | 0.238† | 0.128* | 0.217† |

| Externalizing score (CBCL) (n=325) | -0.203† | 0.511† | 0.396† | -0.268† | -0.139* | -0.122* | 0.391† | 0.415† | 0.426† | 0.396† |

| Reliability | ||||||||||

| Internal consistency | 0.855 | 0.838 | 0.637 | 0.739 | 0.764 | 0.682 | 0.786 | 0.761 | 0.610 | 0.637 |

| Test-retest (95%CI) | 0.738 (0.221-0.912) | 0.872 (0.619-0.957) | 0.930 (0.792-0.977) | 0.761 (0.289-0.920) | 0.691 (0.080-0.896) | 0.834 (0.506-0.944) | 0.803 (0.413-0.934) | 0.853 (0.564-0.951) | 0.790 (0.520-0.870) | 0.930 (0.792-0.977) |

95%CI = 95% confidence interval; ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CBCL = child behavior checklist; CCEB = Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; PSDQ = Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – Short Version; SNAP-IV = Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham – Version IV.

n varies due to missing data.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

We found significant associations of child behavioral and emotional problems with parenting. Children’s inattentive ADHD problems showed a negative association with the authoritative style and its autonomy dimension, and a positive association with the authoritarian style and its three dimensions, as well as with the permissive style. Children’s hyperactive-impulsive problems showed the same pattern of association with the PSDQ styles and dimensions, although the authoritative dimension which correlated negatively with children’s hyperactive-impulsive level was warmth and support, not autonomy. Overall, lower levels of children’s ADHD problems were related to use of the authoritative parenting style, while higher levels were associated with the use of authoritarian and permissive styles. The same pattern was observed for children’s oppositional defiant behaviors. Regarding the broader categories of children’s behavioral and emotional problems, we observed that internalizing problems were positively related to the authoritarian and permissive styles and their dimensions, and negatively associated with the warmth and support dimension. The same pattern of associations was observed for externalizing problems, with even stronger correlations, particularly for the authoritarian style.

Reliability

Reliability results are shown in Table 5. The PSDQ McDonalds’ omega was 0.775 for the complete questionnaire, which is moderately good. The authoritative and authoritarian styles showed higher internal consistency, while the permissive style showed lower internal consistency. None of the PSDQ dimensions showed unacceptable or poor (i.e., ω < 0.6) internal consistency. Test-retest stability was tested by ICCs. All PSDQ styles and dimensions showed excellent ICCs (i.e., ≥ 75), except for the regulation and punitive dimensions, which showed good ICCs (i.e., ≥ 60). Two outliers were removed in the punitive dimension due to their substantial impact on the results.

Discussion

This study aimed to adapt the PSDQ to the Brazilian context and to test the reliability and validity of this version of the scale on a sample of 451 mothers. Besides conducting translation and cross-cultural adaptation through a rigorous method, the present study found significant evidence of validity and reliability for the Brazilian version of the PSDQ.

Validity refers to the degree to which the scale items represent a construct.28 Content validity was measured using CVIs. The minimum optimal CVI is 0.78 for each item29 and 0.90 for the whole scale (S-CVI).30 The questionnaire obtained an S-CVI of 0.97, which is satisfactory. Item 24 (“I spoil our child”) was considered poor in content validity, but was not excluded due to the good final index of the scale.

Using CFA, we tested four factor models described by Pedro et al.27 Only model 1, which tested the original three-factor, second-order solution (i.e., three styles consisting of seven dimensions), was considered suitable in our study. Again, the results of CFA suggest that the Brazilian version of the PSDQ is related to Baumrind’s theory of parenting.2,3

Convergent validity was tested by investigation of the association of the PSDQ styles with the seven parental educational practices of the Brazilian validated IEP. Although the IEP is not based on Baumrind’s theory,23 some of its dimensions are similar to those of the PSDQ. Sampaio & Gomide21 describe lax discipline as not fulfilling rules established by parents, a behavior which is common in the permissive style in Baumrind’s theory, wherein parents lack control of their children.16 The physical abuse dimension of the IEP is described as the use of physical punishment as a form of control of children’s behavior,23 a strategy also used by parents who have an authoritarian style according to Baumrind.2 The moral behavior dimension is described as the ability of parents to convey to their children values such as honesty, generosity, and a sense of justice, helping children to discriminate between right and wrong.21 Negligence, according to Sampaio & Gomide,21 occurs when parents omit their responsibilities to their children or when parents do not attend to their children’s needs. The positive monitoring and negative monitoring dimensions of IEP are not similar to any aspect of Baumrind’s theory. No significant correlations were found between the authoritative scale of PSDQ and any of the dimensions of the IEP. The authoritarian scale was significantly and moderately correlated with the lax discipline and physical abuse dimensions of IEP. There was a strong correlation between the authoritarian scale and negative practices measured by the IEP. For example, the association with the physical abuse scale of the IEP is consistent with Baumrind’s theory, considering that authoritarian parents use physical coercion when their children misbehave. The permissive scale was positively and strongly correlated with the IEP lax discipline dimension, and negatively and moderately correlated with the moral behavior dimension. Both correlations are consistent with Baumrind’s theory, wherein permissive parents are less demanding and avoid using control over their children.23

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, we observed that older and more educated mothers with younger children seem to be more authoritative and less authoritarian. Previous studies also found similar correlations of parenting with maternal education31,32 and children’s age.33 Parenting styles were also associated with children’s behavior problems. As in other studies,34,35 we observed that children’s ADHD problems, such as inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity, were related to higher maternal scores in the authoritarian and permissive styles and lower scores in the authoritative style. The same pattern of association was observed for children’s oppositional defiant behaviors. There is evidence suggesting a clear interaction between negative parenting and oppositional behavior.34 In fact, negative parenting may occur exactly in response to genetically influenced child traits.11 On the other hand, positive parenting practices are beneficial for externalizing behavioral symptoms.36 Using the internalizing and externalizing CBCL dimensions, we found, again, that negative parenting (i.e., authoritarian and permissive strategies) was related to higher behavioral problems in children, while positive parenting (i.e., authoritative strategies) was associated with less behavioral problems, as previously described.3,4,11,37

Reliability aims to verify how much an individual’s score represents the reality and the extent to which this result remains constant over time. Internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, is recognized as acceptable when the coefficient is higher than 0.7.38 However, some researchers consider coefficients above 0.6 to be acceptable for scales with few items or screening tests.38 In this study, the PSDQ Cronbach’s alpha was 0.745 for the complete questionnaire, and none of the PSDQ styles and dimensions showed unacceptable (i.e., < 0.5) internal consistency (range, 0.591 to 0.848). Therefore, the PSDQ showed mainly acceptable to good internal consistency. Additionally, most PSDQ styles and dimensions showed excellent ICCs (i.e., ≥ 75), except for the regulation and punitive dimensions, which showed good ICCs (i.e., ≥ 60). These reliability properties are similar to those obtained for the PSDQ in different countries, including in the original validation of the instrument.10,23,27,37

This study has some limitations. First, the PSDQ was only adapted for self-report use. Further studies with both self-report and spousal report could be more in line with the original idea of the PSDQ, which is an instrument that can be used by mothers or fathers to report their own practices or their spouse’s practices.21 Second, the sample included only mothers, and the range of socioeconomic classes was not representative of the Brazilian population. Future studies with mothers, fathers, and other guardians from different socioeconomic levels could be more representative of Brazilian family structures. Third, although the sample size of the pilot study in the fifth step of adaptation of the scale was in accordance with the guideline used in this study,26 some authors recommend a larger sample to increase item clarity.39 Fourth, there is no consensus on the sample size and statistical power necessary for conducing CFA; therefore, we cannot state that our sample was ideal for this specific analysis. Another limitation was the lower reliability of the permissive style and the punitive dimension. As in the Portuguese version,27 we hypothesize that the Brazilian population may consider permissive items as a natural difficulty in raising children or as positive practices (e.g., “I find it difficult to discipline our child,” “I state punishments to our child and do not actually do them”). Further studies are necessary to overcome the aforementioned limitations. Finally, the merging of clinical and non-clinical samples, as was done for our analysis, is a matter of extensive debate. It is well established in the literature that children’s behavior can change parenting strategies,34 but some authors note that, in validation studies, clinical samples may help increase validity and enable assessment of the construct in a continuum.40

In conclusion, the PSDQ was translated and adapted for use in Brazil through a rigorous methodology, and the resulting version has shown relatively good validity and reliability. This study provides an effective, reliable psychometric instrument to assess childrearing strategies according to Baumrind’s model of parenting styles.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Clyde C. Robinson for granting permission to translate and validate the PSDQ for use in Brazil.

References

- 1.McLeod BD, Weisz JR, Wood JJ. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:986–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967;75:43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumrind D, Black AE. Socialization practices associated with dimensions of competence in preschool boys and girls. Child Dev. 1967;38:291–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK, et al. The relations of parental warmth and positive expressiveness to children’s empathy-related responding and social functioning: a longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2002;73:893–915. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamborn SD, Mounts N, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1991;62:1049–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams LR, Degnan KA, Perez-Edgar KE, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Pine DS, et al. Impact of behavioral inhibition and parenting style on internalizing and externalizing problems from early childhood through adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:1063–75. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9331-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piotrowski JT, Lapierre MA, Linebarger DL. Investigating correlates of self-regulation in early childhood with a representative sample of english-speaking American families. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22:423–36. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9595-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Roper SO, Hart CH. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: development of a new measure. Psychol Rep. 1995;77:819–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ). In: Touliatos J, Perlmutter BF, Straus MA, editors. Handbook of family measurement techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001. pp. 319–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivari MG, Tagliabue S, Confalonieri E. Parenting style and dimensions questionnaire: a review of reliability and validity. Marriage Fam Rev. 2013;49:465–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa FT da, Teixeira MAP, Gomes WB. Responsividade e exigência: duas escalas para avaliar estilos parentais. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2000;13:465–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valentini F. Estudo das propriedades psicométricas do Inventário de Estilos Parentais de Young no Brasil, [thesis]. Natal: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez I, García JF. Internalization of values and self-esteem among Brazilian teenagers from authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful homes. Adolescence. 2008;43:13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paiva FS, Bastos RR, Ronzani TM. Parenting styles and alcohol consumption among Brazilian adolescents. J Health Psychol. 2012;17:1011–21. doi: 10.1177/1359105311428535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power TG. Parenting dimensions and styles: a brief history and recommendations for future research. Child Obes. 2013;9:S14–21. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teixeira MAP, Bardagi MP, Gomes WB. Refinamento de um Instrumento para avaliar responsividade e exigência parental percebidas na adolescência. Aval Psicol. 2004;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasquali L, Gouveia VV, dos Santos WS, da Fonsêca PN, de Andrade JM, de Lima TJS. Perceptions of parents questionnaire: evidence of a measure of parenting styles. Paideia (Ribeirão Preto). 2012;22:155–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benetti SPC, Balbinotti MAA. Elaboração e estudo de propriedades psicométricas do Inventário de Práticas Parentais. Psico-USF. 2003;8:103–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez I, García JF, Camino L, Camino CP dos S. Socialização parental: adaptação ao Brasil da escala ESPA29. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2011;24:640–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampaio ITA, Gomide PIC. Inventário de Estilos Parentais (IEP) – Gomide (2006) Percurso de padronização e normatização. Psicol Argum. 2007;25:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet]. 2014 www.abep.org/criterio-brasil [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miguel I, Valentim JP, Carugati F. Questionário de estilos e dimensões parentais – versão reduzida: adaptação portuguesa do Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – Short Form. Psychologica. 2009;51:169–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattos P, Serra-Pineiro MA, Rohde LA, Pinto D. A Brazilian version of the MTA-SNAP-IV for evaluation of symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional-defiant disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2006;28:290–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The child behavior checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:265–71. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-8-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedro MF, Carapito E, Ribeiro MT. Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – versão portuguesa de autorrelato. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2015;28:302–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorenstein C, Wang YP, Hungerbühler I. Instrumentos de avaliação em saúde mental. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35:382–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:489–97. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn JB, Duncan G. Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers’ parenting, mental health, and social support? J Marriage Fam. 1994;56:441–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belsky J, Bell B, Bradley RH, Stallard N, Stewart-Brown SL. Socioeconomic risk, parenting during the preschool years and child health age 6 years. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:508–13. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frick PJ, Christian RE, Wootton JM. Age trends in the association between parenting practices and conduct problems. Behav Modif. 1999;23:106–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modesto-Lowe V, Danforth JS, Brooks D. ADHD: does parenting style matter? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:865–72. doi: 10.1177/0009922808319963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yousefia S, Far AS, Abdolahian E. Parenting stress and parenting styles in mothers of ADHD with mothers of normal children. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:1666–71. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Healey DM, Flory JD, Miller CJ, Halperin JM. Maternal positive parenting style is associated with better functioning in hyperactive/inattentive preschool children. Infant Child Dev. 2011;20:148–61. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinaldi CM, Howe N. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Child Res Q. 2012;27:266–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitrushina M, Boone KB, Razani J, Delia LF. Handbook of normative data for neuropsychological assessment. Oxford: Oxford University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomaszewski Farias S, Cahn-Weiner DA, Harvey DJ, Reed BR, Mungas D, Kramer JH, et al. Longitudinal changes in memory and executive functioning are associated with longitudinal change in instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;23:446–61. doi: 10.1080/13854040802360558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]