Abstract

The Arctic is undergoing unprecedented environmental change. Rapid warming, decline in sea ice extent, increase in riverine input, ocean acidification and changes in primary productivity are creating a crucible for multiple concurrent environmental stressors, with unknown consequences for the entire arctic ecosystem. Here, we synthesized 30 years of data on the stable carbon isotope (δ13C) signatures in dissolved inorganic carbon (δ13C‐DIC; 1977–2014), marine and riverine particulate organic carbon (δ13C‐POC; 1986–2013) and tissues of marine mammals in the Arctic. δ13C values in consumers can change as a result of environmentally driven variation in the δ13C values at the base of the food web or alteration in the trophic structure, thus providing a method to assess the sensitivity of food webs to environmental change. Our synthesis reveals a spatially heterogeneous and temporally evolving δ13C baseline, with spatial gradients in the δ13C‐POC values between arctic shelves and arctic basins likely driven by differences in productivity and riverine and coastal influence. We report a decline in δ13C‐DIC values (−0.011‰ per year) in the Arctic, reflecting increasing anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) in the Arctic Ocean (i.e. Suess effect), which is larger than predicted. The larger decline in δ13C‐POC values and δ13C in arctic marine mammals reflects the anthropogenic CO2 signal as well as the influence of a changing arctic environment. Combining the influence of changing sea ice conditions and isotopic fractionation by phytoplankton, we explain the decadal decline in δ13C‐POC values in the Arctic Ocean and partially explain the δ13C values in marine mammals with consideration of time‐varying integration of δ13C values. The response of the arctic ecosystem to ongoing environmental change is stronger than we would predict theoretically, which has tremendous implications for the study of food webs in the rapidly changing Arctic Ocean.

Keywords: base of the food web, dissolved inorganic carbon, isoscape, marine mammals, particulate organic matter, sea ice decline, Suess effect, δ13C

Warming of the Arctic has led to changes in multiple environmental factors that control the carbon isotope ratio at the base of the food web. Here, we present the first comprehensive spatial and temporal assessment of the carbon isotopic baseline for the Arctic Ocean, which is essential for understanding and predicting changes in Arctic food web structure. The response of the Arctic ecosystem to ongoing environmental change presented here is stronger than we would predict theoretically.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Arctic is changing rapidly (IPCC, 2013), warming twice as fast as the global average (Carmack et al., 2015; Hoegh‐Guldberg & Bruno, 2010) and causing sea ice to decline in both extent and thickness (Kwok, 2018; Lind, Ingvaldsen, & Furevik, 2018). Sea ice underpins the entire arctic ecosystem and the decline in this seasonal habitat is affecting the entire food web. Primary production has increased by 30% from 1998 to 2012 owing to an increase in light under reduced ice conditions (Arrigo & van Dijken, 2015). Arctic predators, such as seals and polar bears, that rely on sea ice for foraging, moulting and breeding are also adversely affected by the loss of sea ice (Laidre et al., 2008). Other climate‐induced changes are occurring in tandem and include acidification (Yamamoto, Kawamiya, Ishida, Yamanaka, & Watanabe, 2012), shifts in wind patterns and enhanced wind field in the Western Arctic (Overland & Wang, 2010), increased coastal erosion, river flow and melting of permafrost and glaciers (Haine et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2009; Mars & Houseknecht, 2007). These multiple concurrent stressors have far‐reaching implications for the arctic marine ecosystem at multiple trophic levels, and there is an urgent need to understand the ecosystem response in this unique polar habitat.

The ratio of stable carbon isotopes, 13C and 12C, expressed as δ13C (‰), provides a powerful tool for studying food webs. The δ13C values of particulate organic carbon (POC), consisting of fresh phytoplankton, microzooplankton, bacteria and marine and terrestrial detritus, (Fry & Sherr, 1989; Lobbes, Fitznar, & Kattner, 2000; Michener & Kaufman, 2007; Wassmann et al., 2004), represent the base of the food web or ‘baseline’. The δ13C values of POC (δ13C‐POC) are generally transferred with a 13C enrichment of 1‰–2‰ between each trophic level, creating an inextricable link between the base of the food web and consumers (Fry, Anderson, Entzeroth, Bird, & Parker, 1984). Spatial trends in δ13C‐POC values controlled by environmental factors have been used to decipher the foraging and migratory patterns of consumers on a regional scale (Hoffman, 2016; Iken, Bluhm, & Dunton, 2010; Polito et al., 2017; Wassenaar, 2019) and more recently on a global scale in the construction of global ‘isoscapes’ (Bird et al., 2018; Bowen & West, 2008; Firmin, 2016; Graham, Koch, Newsome, McMahon, & Aurioles, 2010; McMahon, Hamady, & Thorrold, 2013b). However, spatial and temporal trends in the δ13C values of high trophic levels may also reflect changes in food web structure such as loss or addition of species, consumer's diet or a combination of factors. To disentangle the drivers of spatial and temporal trends in the δ13C values of consumers in the Arctic, it is crucial to establish spatial and temporal variations in δ13C values at the base of the food web, allowing the sensitivity of marine arctic consumers to environmental change to be quantified.

It is challenging to isolate phytoplankton‐POC for analysis and so the nominal definition of δ13C‐POC values typically assumes that the bulk of POC is derived from phytoplankton only, although δ13C‐POC values can be influenced by other factors such as bacterial activity and detritus (Michener & Kaufman, 2007). While the detrital fraction of POC may be degraded by bacteria, potentially altering the δ13C values of that fraction, we assume that photosynthetic phytoplankton are responsible for transforming the bulk of δ13C‐POC values in time and space. δ13C value of phytoplankton, which underpins the δ13C‐POC values, is controlled by fractionation during photosynthesis. This equates to the difference between the δ13C values of the carbon source, either dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) or carbon dioxide (CO2), and the δ13C‐POC values (Cassar, Laws, Bidigare, & Popp, 2004; Young, Bruggeman, Rickaby, Erez, & Conte, 2013). Factors such as phytoplankton growth rate, availability or concentration of carbon, light and nutrient availability affect isotopic fractionation and the δ13C‐POC values (Burkhardt, Riebesell, & Zondervan, 1999; Keeley & Sandquist, 1992). As such, environmental conditions can create distinct patterns in these values. δ13C‐POC values become enriched in 13C in an environment where replenishment of the CO2 pool is slow or restricted, for example, during periods of rapid phytoplankton growth (Rau, Takahashi, Des Marais, Repeta, & Martin, 1992) or in sea ice associated with sympagic primary production (Budge et al., 2008; Hobson et al., 2002; Søreide et al., 2013; Wang, Budge, Gradinger, Iken, & Wooller, 2014). Conversely, an increase in CO2 concentration will lead to a carbon pool depleted in 13C (Rau et al., 1992) creating a 13C‐deplete POC pool. Terrestrially derived POC delivered via rivers and coastal erosion also tends to be depleted in 13C relative to marine‐derived POC (Boutton, 1991; Keeley & Sandquist, 1992). While global isoscapes capture the large‐scale spatial trends in δ13C values related to oceanographic provinces (shelf vs. open ocean) and latitude (Bird et al., 2018; Bowen & West, 2008; Graham et al., 2010; McMahon et al., 2013b), they do not include the Arctic Ocean. We expect the δ13C values of POC in the Arctic to be influenced by the strong regional trends in sea ice, productivity and terrestrial influence including riverine input and coastal erosion, all of which vary along the water mass circulation pathways from the inflow shelves, which receive water from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, to the arctic basins and interior shelves (Sakshaug, 2004; Tremblay & Gagnon, 2009; Varela, Crawford, Wrohan, Wyatt, & Carmack, 2013).

Imprinted on the regional trends is a temporal trend in δ13C values worldwide. Enhanced atmospheric CO2 since the industrial period (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008) is causing an increase in oceanic CO2 (Sabine et al., 2004) and a decline in the δ13C values of DIC (δ13C‐DIC), known as the Suess effect, as a result of 13C‐depleted anthropogenic CO2 (Quay, Sonnerup, Westby, Stutsman, & McNichol, 2003). δ13C‐DIC values in the Arctic Ocean are predicted to change at a rate of −0.006‰ to −0.008‰ per year, compared to the global average of −0.017‰ per year (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008). However, several studies have already shown that decadal trends in the δ13C values of marine mammals in the Arctic (Misarti, Finney, Maschner, & Wooller, 2009; Nelson, Quakenbush, Mahoney, Taras, & Wooller, 2018; Newsome et al., 2007; Schell, 2001) are larger than the Suess effect alone, implying that other factors are altering their δ13C signatures on decadal timescales.

The main objective of this study was to quantify how regional differences and temporal trends in the arctic environment have altered the δ13C values in DIC and POC, representing the base of the food web or ‘baseline’. We compared these trends at the base of the food web to trends in δ13C values in arctic marine mammals to investigate how environmental change (e.g. Suess effect, loss of sea ice) may alter δ13C values in the entire food web. We synthesized published data from 1977 to 2014 on δ13C values of DIC and dissolved CO2, and δ13C‐POC values in the surface ocean (POCwater) and in sea ice (POCice) across the entire Arctic Ocean, alongside data from arctic rivers (POCriv). We quantified regional differences in the δ13C values in POC and discuss the underlying environmental drivers of the observed spatial heterogeneity. We then quantified the decadal trends in δ13C values of DIC and CO2, and δ13C values of POC in the Arctic Ocean, comparing the rate of change to the Suess effect and observed trends in tissues of arctic marine mammals from the post‐industrial period.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data collation

Data on bulk δ13C‐POCwater, δ13C‐POCice and δ13C‐POCriv values, focusing on suspended particulate organic matter above the thermocline, were collated from tables and figures in 37 original manuscripts and two open access databases for both marine (PANGAEA; http://www.pangaea.de) and riverine (articGRO; https://arcticgreatrivers.org/) environments, in Arctic and sub‐Arctic regions, as defined by the Köppen–Geiger climate classification (Kottek, Grieser, Beck, Rudolf, & Rubel, 2006). The database included 354 data points for marine δ13C‐POCwater values (Brown et al., 2014; Connelly, McClelland, Crump, Kellogg, & Dunton, 2015; Forest et al., 2010; Griffith et al., 2012; Guo, Tanaka, Wang, Tanaka, & Murata, 2004; Hallanger et al., 2011; Hobson, Ambrose, & Renaud, 1995; Hobson et al., 2002; Iken et al., 2010; Iken, Bluhm, & Gradinger, 2005; Ivanov, Lein, Zakharova, & Savvichev, 2012; Kohlbach et al., 2016; Kuliński, Kędra, Legeżyńska, Gluchowska, & Zaborska, 2014; Kuzyk, Macdonald, Tremblay, & Stern, 2010; Lin et al., 2014; Lovvorn et al., 2005; O'Brien, Macdonald, Melling, & Iseki, 2006; Parsons et al., 1989; Roy et al., 2015; Sarà et al., 2007; Schubert & Calvert, 2001; Smith, Henrichs, & Rho, 2002; Søreide et al., 2008; Søreide, Hop, Carroll, Falk‐Petersen, & Hegseth, 2006; Tamelander, Reigstad, Hop, & Ratkova, 2009; Tamelander et al., 2006; Tremblay, Michel, Hobson, Gosselin, & Price, 2006; Zhang et al., 2012), 69 data points for δ13C‐POCice values (Forest et al., 2010; Hobson et al., 1995; 2002; Iken et al., 2005; Kohlbach et al., 2016; Lovvorn et al., 2005; Roy et al., 2015; Schubert & Calvert, 2001; Søreide et al., 2006, 2008; Tamelander et al., 2006; Tremblay et al., 2006) and 383 data points for riverine δ13C‐POCriv values (Goni, Yunker, Macdonald, & Eglinton, 2000; Holmes, McClelland, Tank, Spencer, & Shiklomanov, 2018; Kuzyk et al., 2010; Lobbes et al., 2000). Data were available over different temporal scales: marine δ13C‐POCwater values from 1986 to 2013, δ13C‐POCice from 1993 to 2012 and riverine δ13C‐POCriv values from 1987 to 2016.

To relate the temporal trend in δ13C‐POCwater values to the predicted decline of δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values, a compilation of data on δ13C‐DIC values was extracted from three publications (Bauch, Polyak, & Ortiz, 2015; Schmittner et al., 2013; Young et al., 2013) and two databases (Becker et al., 2016; Key et al., 2015). δ13C‐CO2 values were determined from the δ13C‐DIC values and absolute temperature following the Equation (1) (Rau, Riebesell, & Wolf‐Gladrow, 1996). δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values included 1,333 data points covering 1977–2014.

| (1) |

where T is the temperature in Kelvin.

To determine if the temporal trend in δ13C‐POC values was reflected in higher trophic levels within the Arctic Ocean, δ13C data were collated from arctic marine mammals covering years following the industrial period (post 1950). We collated δ13C data from teeth of ringed seals (Pusa hispida) from 1986 to 2006 from East Greenland (Aubail, Dietz, Rigét, Simon‐Bouhet, & Caurant, 2010) and northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) from 1950 to 2000 from the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska (Newsome et al., 2007). Additionally, δ13C data were collated from teeth of Beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from 1963 to 2008 from the Hudson Bay and from 1976 to 2001 from the Baffin Bay (Matthews & Ferguson, 2014), and baleen plates of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) from 1950 to 1998 from the Bering and Chukchi Seas (Schell, 2001).

2.2. Data treatment

We analysed the δ13C‐POCwater, δ13C‐POCice, δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values in 17 marine arctic regions (Figure 1; Table 1). In addition, the δ13C‐POCwater values from arctic rivers were grouped into two large riverine regions: the Siberian rivers and the North American rivers (Figure 1; Table 1). The regions were defined based on their location, and physical and biological characteristics. Most of the data were collected in summer and δ13C‐POCwater did not vary seasonally (Appendix S1). In order to achieve the best spatial coverage, data from all seasons and years were combined for the spatial comparison. Regional means were calculated for δ13C‐POCwater, δ13C‐POCice, δ13C‐POCriv, δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Map indicating the locations of the arctic regions considered in this study. Circulation pathways are highlighted and modified from Carmack and Wassmann (2006). The yellow arrows represent the intermediate Pacific water and the red arrows represent the Atlantic water. White arrows indicate the mouths of the arctic rivers. The black circles point to the approximate location of the North Water Polynia in the Northern Baffin bay, North‐East Water Polynia in Northeast Greenland and Svalbard marine coastal area. Chu., Churchill River; Gr.Wh., Great Whale River; Hay., Hayes River; Inn., Innuksuac River; Li.Wh., Little Whale River; Nas., Nastapoca River; Nel., Nelson River; Win., Winisk River; Bathymetry and coast lines were from the software Ocean Data View (Schlitzer, 2016)

Table 1.

Location and description of marine regions and rivers, and regional means ± SD of δ13C values in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), ocean dissolved CO2, POCwater, POCice and POCriv

| Marine regions | Description | Regional mean ± SD (n = number of observations) | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C‐DIC (‰) | δ13C‐CO2 (‰) | δ13C‐POCwater (‰) | δ13C‐POCice (‰) | |||

| Outer shelves | ||||||

| South Iceland | Atlantic influenced | 1.3 ± 0.2 (n = 560) | −9.3 ± 0.2 (n = 560) | −19.9 ± 3.3 (n = 4) | NA | Becker et al. (2016); Key et al. (2015); Sarà et al. (2007); Schmittner et al. (2013); Young et al. ( 2013) |

| Norwegian sea | Atlantic influenced | 1.4 ± 0.4 (n = 183) | −10.0 ± 0.4 (n = 183) | NA | NA | Bauch et al. (2015); Becker et al. (2016); Key et al. (2015) |

| Southeast Greenland | Atlantic influenced | 1.3 ± 0.1 (n = 267) | −9.9 ± 0.2 (n = 267) | NA | NA | Becker et al. (2016); Key et al. (2015) |

| Hudson bay | Atlantic influenced; fresh water influenced | NA | NA | −24.7 ± 1.3 (n = 19) | NA | Kuzyk et al. (2010) |

| Bering sea | Pacific influenced | 1.3 ± 0.6 (n = 11) | −9.8 ± 0.8 (n = 11) | −23.9 ± 0.7 (n = 62) | −21.5 ± 0.9 (n = 2) | Guo et al. (2004); Lin et al. (2014); Lovvorn et al. (2005); Schmittner et al. (2013); Smith et al. (2002); Young et al. (2013); Zhang et al. (2012) |

| Gulf of Alaska | Pacific influenced | 0.8 ± 0.2 (n = 50) | −10.3 ± 0.3 (n = 50) | NA | NA | Schmittner et al. (2013); Young et al. (2013) |

| Inflow shelves | ||||||

| Barents sea | Atlantic influenced | 1.0 ± 0.4 (n = 10) | −10.3 ± 0.5 (n = 10) | −23.7 ± 1.6 (n = 12) | −19.3 ± 2.6 (n = 12) | Becker et al. (2016); Søreide et al. (2006); Tamelander et al. (2006, 2009) |

| Svalbard | Northwest of the Barents sea inflow shelf | 1.3 ± 0.4 (n = 17) | −10.0 ± 0.4 (n = 17) | −24.5 ± 0.9 (n = 12) | −23.0 ± 0.7 (n = 6) | Becker et al. (2016); Søreide et al. (2006, 2008); Tamelander et al. (2009) |

| Svalbard fjords | Fresh water influenced; Northwest of the Barents sea inflow shelf | NA | NA | −26.5 ± 1.2 (n = 11) | NA | Hallanger et al. (2011); Kuliński et al. (2014) |

| Chukchi sea | Pacific influenced | 0.8 ± 0.5 (n = 21) | −10.8 ± 0.7 (n = 21) | −22.7 ± 0.1 (n = 36) | NA | Bauch et al. (2015); Iken et al. (2010); Ivanov et al. (2012); Zhang et al. (2012) |

| Interior shelves | ||||||

| Siberian coast | Fresh water influenced; consists of the East Siberian sea | NA | NA | −24.5 ± 0.5 (n = 7) | NA | Iken et al. (2010); Ivanov et al. (2012) |

| Beaufort sea | Fresh water influenced; North American coast | NA | NA | −26.7 ± 2.2 (n = 43) | −26.4 ± 0.5 (n = 8) | Connelly et al. (2015); Forest et al. (2010); Iken et al. (2005); O'Brien et al. (2006); Parsons et al. (1989); Zhang et al. (2012) |

| Outflow shelves | ||||||

| Fram strait | Northeast of Greenland | 1.3 ± 0.4 (n = 102) | −10.5 ± 0.4 (n = 102) | NA | NA | Bauch et al. (2015); Becker et al. (2016) |

| North‐East Water Polynia | Recurring mesoscale areas of open water within areas of pack ice (Sakshaug, 2004); Northeast of Greenland | NA | NA | −27.7 ± 0.6 (n = 3) | −18.6 ± 0.2 (n = 3) | Hobson et al. (1995) |

| North Water Polynia | Recurring mesoscale areas of open water within areas of pack ice (Sakshaug, 2004); North Baffin bay | NA | NA | −21.9 ± 0.6 (n = 30) | −17.7 ± 3.5 (n = 20) | Hobson et al. (2002); Tremblay et al. (2006) |

| Canadian archipelago | Complex straits and channels, terrestrial influence | NA | NA | −25.9 ± 1.4 (n = 21) | −18.9 ± 2.3 (n = 9) | Roy et al. (2015) |

| Arctic basins | ||||||

| Arctic oceanic basins | Includes Amundsen, Nansen and Canadian basins | 1.0 ± 0.2 (n = 134) | −11.1 ± 0.2 (n = 134) | −26.3 ± 1.6 (n = 88) | −22.1 ± 2.4 (n = 9) | Bauch et al. (2015); Brown et al. (2014); Griffith et al. (2012); Ivanov et al. (2012); Kohlbach et al. (2016); Schubert and Calvert (2001); Søreide et al. (2006); Tamelander et al. (2009); Zhang et al. (2012) |

| Riverine regions | Description | δ13C‐POCriv (‰) | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siberian rivers | Includes the large rivers of Lena, Ob and Yenisei and smaller rivers of Kolyma, Indigirka, Yana, Olenek, Vakina and Mezen | NA | NA | −29.5 ± 2.1 (n = 237) | NA | Holmes et al. (2018); Lobbes et al. (2000) |

| North American rivers | Consists of the large rivers of Mackenzie and Yukon, as well as the smaller rivers surrounded the Hudson Bay (Figure 1) | NA | NA | −29.5 ± 1.7 (n = 146) | NA | Goni et al. (2000); Holmes et al. (2018); Kuzyk et al. (2010) |

The decadal variation of regional marine δ13C‐POCwater values in arctic regions was assessed where data were available for at least three different years covering a period of at least 5 years. This included the following regions: arctic basins, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea and Bering Sea. Svalbard and the Barents Sea, which had similar δ13C‐POCwater values and δ13C‐POCice values (Table S2: ANOVA3 and 4), were combined into the ‘European Arctic’ to achieve the best temporal coverage. The mean decadal trend (all regions combined) was calculated for δ13C‐POCwater, δ13C‐POCice, δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Quantile–quantile plots of the residuals were plotted to check how closely the data follow a normal distribution (Becker, Chambers, & Wilks, 1988). The data were normally distributed, and therefore, we used a one‐way ANOVA (α = 0.005; Zuur, Ieno, & Smith, 2007) followed by post hoc Tukey pairwise comparison tests in R (R Core Team, 2018) to spatially compare: (a) the δ13C‐POCwater data between arctic shelves and arctic basins (ANOVA1), between arctic shelves and arctic rivers (ANOVA2) and between all arctic shelves (ANOVA3); and (b) the δ13C‐POCice values between all marine arctic regions where data were available (ANOVA4). We used a two‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey pairwise comparison test to compare the δ13C‐POCice values with δ13C‐POCwater values (factor ‘origin’) for regions (factor ‘region’) where both data sets were available (ANOVA5). Arctic regions with less than five data points were excluded from statistical analyses. Relevant p‐values of the post hoc Tukey pairwise comparison tests following ANOVA1 to 5 are shown in Table S2.

We applied linear models in R (R Core Team, 2018) to quantitatively assess the latitudinal gradient in δ13C‐DIC, δ13C‐CO2 and δ13C‐POCwater values, and the temporal trends in δ13C values of marine POCwater, POCice, DIC, dissolved CO2 and arctic marine mammals. The significance and robustness of the linear models were assessed based on the p‐values of the slopes and intercepts, the R 2, the F‐values and df (Table S3; Zuur et al., 2007).

3. RESULTS

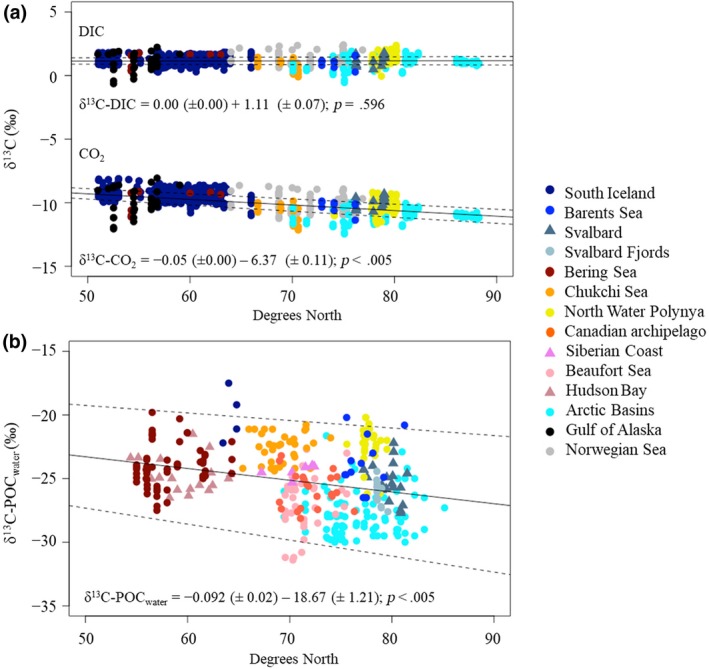

3.1. Spatial trends in the δ13C of the baseline

The Atlantic and Pacific waters entering the Arctic via the South Iceland and Norwegian Sea, and Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea, respectively (Figure 1; Table 1), had similar δ13C‐CO2 values and were depleted by up to 2‰ relative to the δ13C‐CO2 values in the arctic basins (Table 1). We observed a significant depletion in δ13C‐CO2 and δ13C‐POCwater values with increasing latitude (Figure 2). δ13C‐DIC did not vary with latitude (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Stable carbon isotope values (δ13C, in ‰) of (a) marine dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC; n = 1,333) and marine dissolved CO2 (n = 1,333) and (b) marine POCwater (n = 354) in the surface waters with latitude; each dot is a single data point; the solid line represents the slope of the linear regression; dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval of the linear regression. The equations and p‐values of the linear regressions are shown on the figure. Trends are considered significant when p < .005

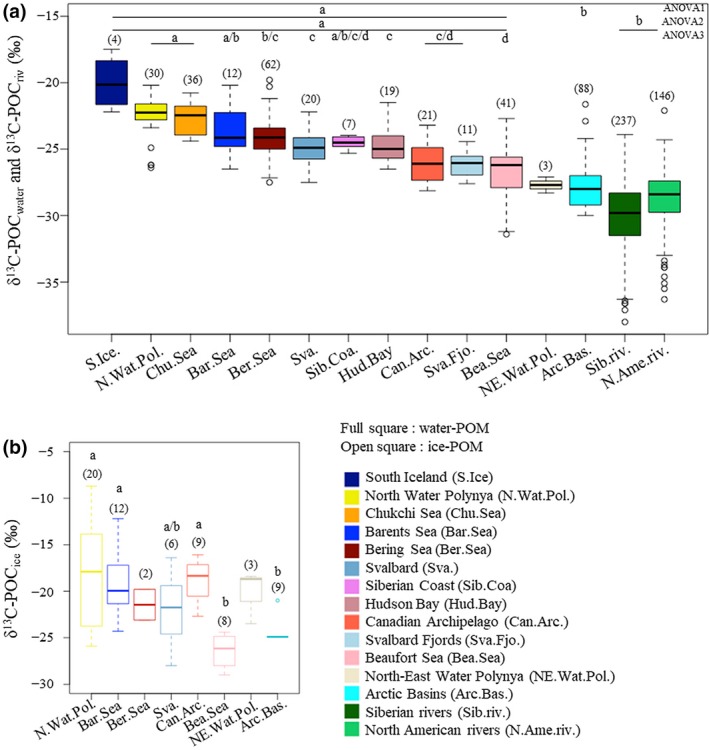

We analysed the δ13C‐POCwater, δ13C‐POCice and δ13C‐CO2 values in 17 marine arctic regions (Figure 1; Table 1). δ13C values of POCwater varied significantly between arctic regions (Figure 3a). POCwater from arctic shelves was significantly enriched in 13C compared to POCwater from arctic basins and POCriv (Figure 3a; Table S2: ANOVA1 and ANOVA2). The δ13C‐POCwater values were 13C depleted in arctic shelves (Beaufort Sea, Svalbard fjords, Canadian archipelago and the Hudson Bay) influenced by fresh water (Table 1; Figure 1) relative to the inflow (Chukchi Sea and Barents Sea) shelves and the North Water Polynya (Figure 3a; Table S2: ANOVA3).

Figure 3.

Regional stable carbon isotope values (δ13C, in ‰) of (a) POCwater and POCriv and (b) POCice; Numbers of observations are shown as number on top of the boxplots. Results of post hoc Tukey tests following (a) ANOVA1 to ANOVA3 and (b) ANOVA4 are expressed as letters on top of the boxplots. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < .005) between regions. The p‐values of each test are shown in Table S2

δ13C‐POCice values followed the same regional trend as δ13C‐POCwater values, with δ13C‐POCice values enriched in 13C in the inflow and outflow shelves (Barents Sea, North Water Polynya) compared to the interior shelf Beaufort Sea and the arctic basins (Figure 3b; Table S2: ANOVA4).

3.2. Comparison between δ13C of POCice and POCwater

Generally, δ13C values of POCice were significantly 13C‐enriched compared to those of POCwater (p < .005; Table S2: ANOVA5), with δ13C‐POCwater being enriched by 4.4‰ in the Barents Sea, by 4.2‰ in the North Water Polynya and by 7.0‰ in the Canadian archipelago (Table 1). There were no significant differences between POCice and POCwater in the Svalbard region, the arctic basins and the Beaufort Sea (Table S2: ANOVA5). δ13C‐POCice values were highly variable in most of the arctic regions (Figure 3b).

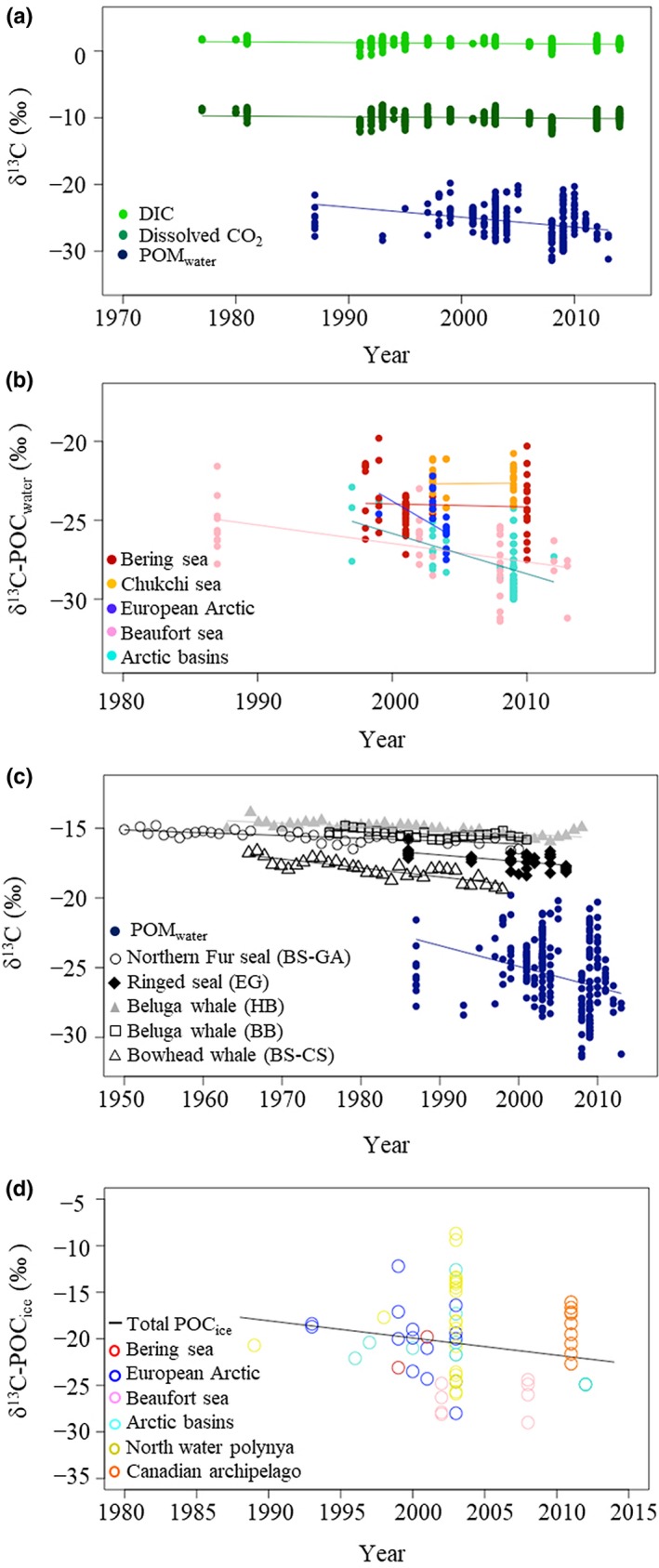

3.3. Temporal trends in the δ13C of the baseline and Arctic marine mammals

In all arctic regions combined, δ13C‐DIC (1977–2014), δ13C‐CO2 (1977–2014) and δ13C‐POCwater (1986–2013) values became significantly 13C depleted by 0.011 ± 0.001, 0.011 ± 0.002 and 0.149 ± 0.020‰ per year respectively (Figure 4a; Table 2). The temporal trends in δ13C‐POCwater values were statistically significant in the Beaufort Sea (−0.117 ± 0.033‰ per year; 1987–2013) and in the arctic basins (−0.256 ± 0.057‰ per year; 1997–2012) and not statistically significant in the European Arctic, Bering Sea and Chukchi Sea (Figure 4b; Table 2; Table S3). The temporal trend in δ13C‐POCice values was not significant (Figure 4d; Table 2; Table S3). The δ13C values in the teeth of northern fur seals, ringed seals and beluga whales, and in baleen plates of bowhead whales were significantly depleted in 13C with time (Figure 4c; Table 2). The decline in δ13C values in teeth ranged from 0.020 ± 0.003‰ per year in northern fur seals from the Gulf of Alaska (1950–2000) to −0.046 ± 0.012‰ per year in ringed seals from East Greenland (1986–2006; Table 2). The δ13C in the baleen plates of bowhead whales from the Bering and Chukchi Seas significantly decreased by 0.064 ± 0.010‰ per year (1965–1998; Table 2). The decline in δ13C values of POCwater and marine mammals was larger than decline in δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values (0.011‰ per year, this study). Details of the linear models are shown in Table S3.

Figure 4.

Decadal trend in δ13C values of: (a) dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), dissolved CO2 and POCwater, (b) POCwater for each arctic region, (c) POCwater and arctic marine mammal tissues and (d) POCice for each arctic region. BS, Bering sea; CS, Chukchi sea; EG, East Greenland; GA, Gulf of Alaska; HB, Hudson bay. Results of the linear models can be found in Table 2 and Table S3. Number of observations can be found in Table 2

Table 2.

Slopes ± SD and p‐values of the decadal linear models of δ13C values in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), ocean dissolved CO2, POCwater, POCice and arctic marine mammal tissues

| Slope ± SD | p‐value | Time period | Number of observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCwater | ||||

| Beaufort sea | −0.117 ± 0.033 | <.005 | 1987–2013 | 71 |

| European Arctic | −0.499 ± 0.265 | .076 | 1999–2004 | 20 |

| Arctic basins | −0.256 ± 0.057 | <.005 | 1997–2012 | 87 |

| Bering sea | −0.019 ± 0.046 | .679 | 1998–2010 | 62 |

| Chukchi sea | +0.008 ± 0.071 | .906 | 2003–2009 | 36 |

| All data | −0.149 ± 0.020 | <.005 | 1987–2013 | 311 |

| POCice | ||||

| All data | −0.185 ± 0.106 | .084 | 1993–2012 | 69 |

| DIC | ||||

| All data | −0.011 ± 0.001 | <.005 | 1977–2014 | 1,333 |

| CO2 | ||||

| All data | −0.011 ± 0.002 | <.005 | 1977– 2014 | 1,333 |

| Marine mammals | ||||

| Northern fur seal—Bering sea/Gulf of Alaska | −0.020 ± 0.003 | <.005 | 1950–2000 | 40 |

| Ringed seal—East Greenland | −0.046 ± 0.012 | <.005 | 1986–2006 | 36 |

| Beluga whale—Hudson Bay | –0.026 ± 0.003 | <.005 | 1963–2008 | 42 |

| Beluga whale—Baffin Bay | –0.021 ± 0.006 | <.005 | 1976–2001 | 26 |

| Bowhead whale—Bering sea/Chukchi sea | −0.064 ± 0.007 | <.005 | 1965–1998 | 34 |

Lines in bold are considered significant (p < .005).

Detailed statistics of the linear models are shown in Table S3.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Ice versus water

The 13C‐enrichment in POCice compared to POCwater in arctic regions has been observed previously and attributed to carbon limitation around ice algae within sea ice (Budge et al., 2008; Hobson et al., 2002; Søreide et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2014). The termination of the spring ice edge bloom can cause 13C at the base of the food web to be altered when 13C‐enriched ice algae were added to 13C‐depleted pelagic phytoplankton (Søreide et al., 2006). The similarity in the δ13C‐POCice and δ13C‐POCwater values in some regions (see Section 2.2) and the high intra‐regional variability of the δ13C‐POCice values may be explained by differences in ice porosity, allowing replenishment of DIC from water to ice (Thomas & Papadimitriou, 2011). δ13C‐POCice values were likely to have been influenced by light availability and the high bacterial activity in sea ice compared to open water (Wang et al., 2014). Thus, variation in the sampling month for sea ice might also contribute to the high variability in δ13C‐POCice. This highlights that caution is required when using bulk δ13C values of POCice and POCwater to distinguish between open water versus ice‐dependent food webs in the Arctic (Søreide et al., 2006). The challenge of disentangling the contribution of carbon derived from sympagic production to the food web has been successfully resolved by using compound‐specific stable isotope analyses (e.g. δ13C values of fatty acids; Graham, Oxtoby, Wang, Budge, & Wooller, 2014; Oxtoby, Budge, Iken, Brien, & Wooller, 2016; Oxtoby et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015).

4.2. Spatial trends

Spatial trends in the δ13C values of POCwater and POCice were similar, implying that they were influenced by the same environmental drivers within specific regions of the Arctic Ocean.

Low temperature, high wind speed and high productivity enhance the atmospheric CO2 uptake by the Arctic Ocean (Takahashi et al., 2002), driving strong latitudinal gradients in concentration and δ13C values of oceanic CO2 with 13C‐CO2 being more depleted in the Arctic Ocean (≈−10‰, Young et al., 2013; −10.2 ± 0.5‰, this study) relative to the tropics (≈−7 ‰, Young et al., 2013). In the marine environment, more than 90% of DIC is composed of bicarbonate ions (; Boutton, 1991). Fractionation between and atmospheric CO2 increases in cold water (Zhang, Quay, & Wilbur, 1995) leading to 13C enrichment of δ13C‐DIC values with increasing latitude (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008), as observed in this study (Figure 2a). δ13C‐POCwater values became 13C‐depleted with increasing latitude (Figure 2b, this study; Goericke & Fry, 1994; McMahon et al., 2013b), reflecting the latitudinal trend in δ13C‐CO2 values as well as multiple additional factors, including temperature, phytoplankton growth rates, bacterial activity and isotopic fractionation, that also vary with latitude (Fouilland et al., 2018; Thomas, Kremer, Klausmeier, & Litchman, 2012; Young et al., 2013). A latitudinal trend in δ13C values of zooplankton was observed in the western Arctic (i.e. Bering and Chukchi Sea; Dunton, Saupe, Golikov, Schell, & Schonberg, 1989), demonstrating the transfer of this δ13C signature to the next trophic level.

The two orders of magnitude difference in phytoplankton production between the nutrient‐rich arctic shelves and the ice covered nutrient depleted arctic basin (Sakshaug, 2004) may partially explain the relatively large difference in δ13C‐POCwater values of 2.3‰ between the arctic shelf (−24.0 ± 1.2‰) and arctic basins (−26.3 ± 1.6‰). High rates of primary production cause 13C enrichment of the δ13C‐POC values (Boutton, 1991; McMahon, Hamady, & Thorrold, 2013a). The highly productive Bering Sea and Barents Sea account for up to two‐thirds of the total arctic phytoplankton production (Sakshaug, 2004). Advection of nutrients from the arctic outflow and early exposure to sunlight enhance phytoplankton productivity in the North Water Polynya (Sakshaug, 2004). In contrast, high turbidity and strong stratification caused by fresh water inflow from rivers onto the interior shelves reduce light and restrict phytoplankton production (Dittmar & Kattner, 2003). Lower phytoplankton productivity in the river influenced Beaufort Sea and Siberian Coast, as well as the North‐East Water Polynia (Sakshaug, 2004) could explain the depleted δ13C‐POC values observed in these regions relative to the more productive regions.

The 13C depletion in δ13C‐POCwater values observed in the interior shelves, Svalbard fjords, Hudson Bay and Canadian archipelago compared to other arctic shelf regions likely reflects the contribution of 13C‐depleted terrestrially derived POC (Boutton, 1991) from rivers, coastal erosion and glacial streams. Seventy‐two arctic rivers supplying 40% of the total freshwater input from the surrounding continents of Eurasia and North America enter the Arctic Ocean via the interior shelves of the Siberian coast and the Beaufort Sea (Table 1; Figure 1) at a rate of 2,500–4,200 km3/year (Haine et al., 2015). In addition, terrestrially derived POC input resulting from coastal erosion may be equal to or larger than input from river discharge in some regions, for instance along the Siberian coast (Rachold et al., 2000). Finally, glacial fjords on Svalbard are fed with freshwater by large glaciers and streams with the highest freshwater inflow in summer during ice and snow melt (Cottier et al., 2005). Any temporal alteration of the riverine inputs or the drainage basins would likely alter the δ13C‐POCwater values in the interior shelves and subsequently alter the base of the food web.

4.3. Temporal trends at the baseline

The increasing concentration of anthropogenic CO2, known as the Suess effect, is predicted to decrease the oceanic δ13C‐DIC values by an average of 0.017‰ per year, with high spatial variability from 0‰ per year in the Southern Ocean to 0.024‰ per year in the subtropical gyres (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008). In the Arctic Ocean, the δ13C‐DIC values are predicted to decrease by 0.006‰ to 0.008‰ per year (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008). We observed a decreasing trend in δ13C‐DIC values of 0.011 ± 0.001‰ per year from 1977 to 2014 across all arctic regions, which is larger than the predicted trend. Although CO2 represents less than 0.5% of the total DIC pool, it is the only component that is exchangeable with the atmosphere. In polar regions, especially the Arctic Ocean, the decline in sea ice has led to an expansion of open water (Arrigo & van Dijken, 2015). This facilitates atmospheric exchange and enhances the dissolved CO2 concentration (Yamamoto et al., 2012) resulting in an additional 13C depletion of δ13C‐CO2 values (Rau et al., 1992) which may explain the larger decrease in δ13C‐CO2 values (0.011 ± 0.002‰ per year) and in turn the larger decrease in δ13C‐DIC values (0.011 ± 0.001‰ per year) in the Arctic Ocean compared to the predicted decrease of 0.006–0.008‰ per year (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008).

The decadal decline in δ13C‐POCwater values (1987–2013) was more than 10 times larger than the trend in δ13C values of CO2 (or DIC) implying that other factors are influencing the δ13C values in POC in the Arctic Ocean. Since the mid‐1990s, sea ice extent has declined by 8.3 ± 0.6% per decade across the entire Arctic (Comiso, 2012). Sea ice algae are up to 7 ‰ enriched in 13C relative to pelagic phytoplankton (this study) and a decline in sea ice could decrease the contribution of ice algal biomass to total productivity and reduce the total mean δ13C values of POCwater. For example, the open water area of the Barents sea has increased by 15,789 km2 or 1.3% per year between 1998 and 2012, alongside a 28% increase in net primary production over the same time period (Arrigo & van Dijken, 2015). Assuming distinct end members for δ13C‐POCwater (−25.0 ± 1.7‰) and δ13C‐POCice (−20.0 ± 1.3‰) values, sea ice decline would cause the entire pool of δ13C‐POC values to decrease by 0.06 ± 0.15‰ per year. Additionally, the photosynthetic isotopic fractionation factor for phytoplankton in the Arctic Ocean has increased by 0.045‰ per year since the 1960s, compared to a global average of 0.022‰ per year (Young et al., 2013). The combined effect of a decline in ice algae (0.06 ± 0.15‰ per year, this study), increase in fractionation factor (0.045‰ per year, Young et al., 2013) and Suess effect (i.e. dissolved CO2, 0.011 ± 0.001‰ per year, this study) could potentially cause the δ13C‐POC values to decrease by 0.116 ± 0.15‰ per year, which is of the same order of magnitude as the observed annual decrease in δ13C‐POCwater values in the whole Arctic (0.149 ± 0.028‰ per year) and in the Beaufort Sea (0.126 ± 0.020‰ per year; Table 2). In support of this argument, the difference between the temporal trend or slope in δ13C‐CO2 and δ13C‐POC values (Figure 4a) increased by 0.138 ± 0.028‰ per year in agreement with the sum of the contributions from a change in ice (0.06 ± 0.15‰ per year), fractionation (0.045‰ per year) and Suess effect (0.011 ± 0.001‰ per year) influencing δ13C‐POCwater values.

Other factors contributing to the decline in δ13C‐POC values in the Arctic Ocean include river run‐off, coastal erosion, primary production and bacterial activity. Increased riverine run‐off (Haine et al., 2015) and coastal erosion (Jones et al., 2009; Mars & Houseknecht, 2007) resulting from ongoing climate change in the Arctic could contribute to the decline in δ13C‐POC values by adding 13C‐deplete terrestrially derived material to the marine POC pool. Changes in primary productivity will also influence the δ13C‐POC values. For example, the decline of δ13C values in Bowhead whales from the Bering/Chukchi Sea was interpreted by Schell (2000) as reflecting a 30%–40% decrease in seasonal primary productivity in the Bering Sea over the last 30 years. Increasing bacterial activity with increasing temperature (Vaqué et al., 2019; Vernet, Richardson, Metfies, Nöthig, & Peeken, 2017) and dissolved CO2 concentration (Grossart, Allgaier, Passow, & Riebesell, 2006) in the Arctic may also influence the δ13C values of POC.

4.4. Implications for food web

The reliability of stable carbon isotopes in deciphering the provenance of feeding or migratory patterns of consumers is heavily dependent on knowledge of δ13C values at the base of the food web. Maps that convey the geographical and temporal trends of δ13C values in the baseline, termed isoscapes (Bowen et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2010), have become a necessity for interpreting trophic structure using δ13C (or δ15N) values (Hansen, Hedeholm, Sünksen, Christensen, & Grønkjær, 2012; Newsome, Clementz, & Koch, 2010). Although isoscapes have been constructed for the atmosphere (Bowen et al., 2009), terrestrial environment (Bowen & West, 2008; Firmin, 2016) and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (Graham et al., 2010; McMahon et al., 2013b), this study provides a first view of δ13C‐POC values or carbon isoscape of the Arctic Ocean. We found spatially heterogeneous and temporally evolving δ13C values in the POC pool, which has ramifications for the study of food webs in space and time.

Previous studies have noted that the decline in δ13C in Arctic marine mammals is larger than the Suess effect alone (e.g. Matthews & Ferguson, 2014; Newsome et al., 2007), but the lack of δ13C baseline information prevented these authors from disentangling the driving factors (Cullen, Rosenthal, & Falkowski, 2001; Schell, 2000, 2001). Generally, the temporal decline in the δ13C values in marine mammals was larger than in δ13C‐DIC and δ13C‐CO2 values (both of −0.011 ± 0.001‰ per year) but smaller than the decline observed in δ13C‐POCwater values (−0.149 ± 0.028‰ per year). The δ13C signature in phytoplankton or a consumer represents an average ratio related to the lifetime of the organism and tissue turnover time (Vander Zanden, Clayton, Moody, Solomon, & Weidel, 2015). Previous studies have shown that the seasonal variation in δ13C values of POC was higher than in higher trophic levels reflecting the strong seasonal growth cycle of phytoplankton and shorter time period over which they integrate carbon (O'reilly, Hecky, Cohen, & Plisnier, 2002). In contrast, consumers from zooplankton to predators are long‐lived and thus integrate δ13C values over their seasonal foraging and migratory routes (Aubail et al., 2010; Schell, Saupe, & Haubenstock, 1989) with the time of integration depending on the tissue type (Vander Zanden et al., 2015) or the animals’ lifetime (O'reilly et al., 2002). The effect of yearly averaging of the δ13C values in marine mammal teeth and baleen plates used to reconstruct decadal trends may have reduced the larger, short‐lived variation observed in δ13C‐POC values mainly representing summer in this study. The gradual linear decline in δ13C values in arctic seals and whales likely reflects alterations to the δ13C‐POC values. A change in diet, for example, a shift towards foraging closer to freshwater (Nelson et al., 2018), or more pelagic feeding habits (Aubail et al., 2010), may also contribute to the temporal decline in δ13C values observed in predators.

This study demonstrates that to disentangle factors driving variation in the δ13C values in a consumer, it is vital to know the spatial heterogeneity and temporal evolution of δ13C values of the baseline in the Arctic Ocean in order to avoid inaccurate interpretation of changes in food web structures. Some studies have attempted to correct the δ13C values in arctic marine mammals for the Suess effect using modelled and predicted values for large geographical regions, prior to interpreting decadal trends in δ13C values (Carroll, Horstmann‐Dehn, & Norcross, 2013; Misarti et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2018). However, the Suess effect varies spatially (Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008), and therefore, local values should be used for this correction. For example, the Suess effect in the Arctic Ocean (0.011 ± 0.001‰ per year, this study) differs from the predicted modelled values (0.006–0.008‰ per year; Tagliabue & Bopp, 2008), implying that other factors, such as the loss of sea ice, are accelerating the influence of anthropogenic CO2 in the Arctic. In addition, the decline in δ13C‐POC values, representing the base of the food web, is larger than the decline in δ13C‐DIC values (this study). This suggests that interpretation about diet shift should be done after consideration of temporal trends in δ13C‐POC values and not only in δ13C‐DIC (Suess effect). These results also highlight the importance of considering time‐averaging effects when studying different trophic levels and/or tissues having, respectively, variable lifetime and turnover time. Insight from this study has direct implications for how we interpret changes in δ13C values in consumers, especially in environments experiencing rapid change.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work resulted from the ARISE project (NE/P006035/1 and NE/P006310/1), part of the Changing Arctic Ocean programme, jointly funded by the UKRI Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). We declare that none of the authors has any competing financial and/or non‐financial interests in relation to the work described.

de la Vega C, Jeffreys RM, Tuerena R, Ganeshram R, Mahaffey C. Temporal and spatial trends in marine carbon isotopes in the Arctic Ocean and implications for food web studies. Glob Change Biol. 2019;25:4116–4130. 10.1111/gcb.14832

REFERENCES

- Arrigo, K. R. , & van Dijken, G. L. (2015). Continued increases in Arctic Ocean primary production. Progress in Oceanography, 136, 60–70. 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aubail, A. , Dietz, R. , Rigét, F. , Simon‐Bouhet, B. , & Caurant, F. (2010). An evaluation of teeth of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) from Greenland as a matrix to monitor spatial and temporal trends of mercury and stable isotopes. Science of the Total Environment, 408(21), 5137–5146. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch, D. , Polyak, L. , & Ortiz, J. (2015). A baseline for the vertical distribution of the stable carbon isotopes of dissolved inorganic carbon (δ13C‐DIC) in the Arctic Ocean. Arktos, 1(1), 15 10.1007/s41063-015-0001-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M. , Andersen, N. , Erlenkeuser, H. , Humphreys, M. P. , Tanhua, T. , & Körtzinger, A. (2016). An internally consistent dataset of δ13C‐DIC in the North Atlantic Ocean–NAC13v1. Earth System Science Data, 8(2), 559–570. 10.5194/essd-8-559-2016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, R. A. , Chambers, J. M. , & Wilks, A. R. (1988). The new S language: A programming environment for data analysis and graphics. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, C. S. , Veríssimo, A. , Magozzi, S. , Abrantes, K. G. , Aguilar, A. , Al‐Reasi, H. , … Trueman, C. N. (2018). A global perspective on the trophic geography of sharks. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2(2), 299–305. 10.1038/s41559-017-0432-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutton, T. W. (1991). Stable carbon isotope ratios of natural materials: II. Atmospheric, terrestrial, marine and freshwater environments In Coleman D. C. & Fry B. (Eds.), Carbon isotope techniques (pp. 173–186). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G. J. , & West, J. B. (2008). Isotope landscapes for terrestrial migration research. Terrestrial Ecology, 2, 79–105. 10.1016/s1936-7961(07)00004-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G. J. , West, J. B. , Vaughn, B. H. , Dawson, T. E. , Ehleringer, J. R. , Fogel, M. L. , … Still, C. J. (2009). Isoscapes to address large‐scale earth science challenges. EOS, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 90(13), 109–110. 10.1029/2009EO130001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K. A. , McLaughlin, F. , Tortell, P. D. , Varela, D. E. , Yamamoto‐Kawai, M. , Hunt, B. , & Francois, R. (2014). Determination of particulate organic carbon sources to the surface mixed layer of the Canada Basin, Arctic Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(2), 1084–1102. 10.1002/2013JC009197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budge, S. , Wooller, M. , Springer, A. , Iverson, S. J. , McRoy, C. , & Divoky, G. (2008). Tracing carbon flow in an arctic marine food web using fatty acid‐stable isotope analysis. Oecologia, 157(1), 117–129. 10.1007/s00442-008-1053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, S. , Riebesell, U. , & Zondervan, I. (1999). Stable carbon isotope fractionation by marine phytoplankton in response to daylength, growth rate, and CO2 availability. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 184, 31–41. 10.3354/meps184031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmack, E. , Polyakov, I. , Padman, L. , Fer, I. , Hunke, E. , Hutchings, J. , … Winsor, P. (2015). Toward quantifying the increasing role of oceanic heat in sea ice loss in the New Arctic. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 96(12), 2079–2105. 10.1175/bams-d-13-00177.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmack, E. , & Wassmann, P. (2006). Food webs and physical–biological coupling on pan‐Arctic shelves: Unifying concepts and comprehensive perspectives. Progress in Oceanography, 71(2), 446–477. 10.1016/j.pocean.2006.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. S. , Horstmann‐Dehn, L. , & Norcross, B. L. (2013). Diet history of ice seals using stable isotope ratios in claw growth bands. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 91(4), 191–202. 10.1139/cjz-2012-0137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, N. , Laws, E. A. , Bidigare, R. R. , & Popp, B. N. (2004). Bicarbonate uptake by Southern Ocean phytoplankton. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 18(2). 10.1029/2003GB002116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comiso, J. C. (2012). Large decadal decline of the arctic multiyear ice cover. Journal of Climate, 25(4), 1176–1193. 10.1175/jcli-d-11-00113.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, T. L. , McClelland, J. W. , Crump, B. C. , Kellogg, C. T. , & Dunton, K. H. (2015). Seasonal changes in quantity and composition of suspended particulate organic matter in lagoons of the Alaskan Beaufort Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 527, 31–45. 10.3354/meps11207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cottier, F. , Tverberg, V. , Inall, M. , Svendsen, H. , Nilsen, F. , & Griffiths, C. (2005). Water mass modification in an Arctic fjord through cross‐shelf exchange: The seasonal hydrography of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110 10.1029/2004jc002757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J. T. , Rosenthal, Y. , & Falkowski, P. G. (2001). The effect of anthropogenic CO2 on the carbon isotope composition of marine phytoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography, 46(4), 996–998. 10.4319/lo.2001.46.4.0996 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, T. , & Kattner, G. (2003). The biogeochemistry of the river and shelf ecosystem of the Arctic Ocean: A review. Marine Chemistry, 83(3–4), 103–120. 10.1016/S0304-4203(03)00105-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton, K. H. , Saupe, S. M. , Golikov, A. N. , Schell, D. M. , & Schonberg, S. V. (1989). Trophic relationships and isotopic gradients among arctic and subarctic marine fauna. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 56, 89–97. 10.3354/meps056089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firmin, S. M. (2016). The spatial distribution of terrestrial stable carbon isotopes in North America, and the impacts of spatial and temporal resolution on static ecological models. University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Forest, A. , Galindo, V. , Darnis, G. , Pineault, S. , Lalande, C. , Tremblay, J.‐É. , & Fortier, L. (2010). Carbon biomass, elemental ratios (C:N) and stable isotopic composition (δ13C, δ15N) of dominant calanoid copepods during the winter‐to‐summer transition in the Amundsen Gulf (Arctic Ocean). Journal of Plankton Research, 33(1), 161–178. 10.1093/plankt/fbq103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouilland, E. , Floc'h, E. L. , Brennan, D. , Bell, E. M. , Lordsmith, S. L. , McNeill, S. , … Leakey, R. J. G. (2018). Assessment of bacterial dependence on marine primary production along a northern latitudinal gradient. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 94(10), fiy150 10.1093/femsec/fiy150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry, B. , Anderson, R. K. , Entzeroth, L. , Bird, J. L. , & Parker, P. L. (1984). 13C enrichment and oceanic food web structure in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Contributions in Marine Science, 27, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, B. , & Sherr, E. B. (1989). δ13C measurements as indicators of carbon flow in marine and freshwater ecosystems In Rundel P. W., Ehleringer J. R., & Nagy K. A. (Eds.), Stable isotopes in ecological research (pp. 196–229). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goericke, R. , & Fry, B. (1994). Variations of marine plankton δ13C with latitude, temperature, and dissolved CO2 in the world ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 8(1), 85–90. 10.1029/93gb03272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goni, M. A. , Yunker, M. B. , Macdonald, R. W. , & Eglinton, T. I. (2000). Distribution and sources of organic biomarkers in arctic sediments from the Mackenzie River and Beaufort Shelf. Marine Chemistry, 71(1–2), 23–51. 10.1016/S0304-4203(00)00037-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B. S. , Koch, P. L. , Newsome, S. D. , McMahon, K. W. , & Aurioles, D. (2010). Using isoscapes to trace the movements and foraging behavior of top predators in oceanic ecosystems In West J. B., Bowen G. J., Dawson T. E., & Tu K. P. (Eds.), Isoscapes (pp. 299–318). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C. , Oxtoby, L. , Wang, S. W. , Budge, S. M. , & Wooller, M. J. (2014). Sourcing fatty acids to juvenile polar cod (Boreogadus saida) in the Beaufort Sea using compound‐specific stable carbon isotope analyses. Polar Biology, 37(5), 697–705. 10.1007/s00300-014-1470-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D. R. , McNichol, A. P. , Xu, L. , McLaughlin, F. A. , Macdonald, R. W. , Brown, K. A. , & Eglinton, T. I. (2012). Carbon dynamics in the western Arctic Ocean: Insights from full‐depth carbon isotope profiles of DIC, DOC, and POC. Biogeosciences, 9(3), 1217–1224. 10.5194/bg-9-1217-2012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossart, H.‐P. , Allgaier, M. , Passow, U. , & Riebesell, U. (2006). Testing the effect of CO2 concentration on the dynamics of marine heterotrophic bacterioplankton. Limnology and Oceanography, 51(1), 1–11. 10.4319/lo.2006.51.1.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. , Tanaka, T. , Wang, D. , Tanaka, N. , & Murata, A. (2004). Distributions, speciation and stable isotope composition of organic matter in the southeastern Bering Sea. Marine Chemistry, 91(1–4), 211–226. 10.1016/j.marchem.2004.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haine, T. W. N. , Curry, B. , Gerdes, R. , Hansen, E. , Karcher, M. , Lee, C. , … Woodgate, R. (2015). Arctic freshwater export: Status, mechanisms, and prospects. Global and Planetary Change, 125, 13–35. 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.11.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallanger, I. G. , Ruus, A. , Warner, N. A. , Herzke, D. , Evenset, A. , Schøyen, M. , … Borgå, K. (2011). Differences between Arctic and Atlantic fjord systems on bioaccumulation of persistent organic pollutants in zooplankton from Svalbard. Science of the Total Environment, 409(14), 2783–2795. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J. H. , Hedeholm, R. B. , Sünksen, K. , Christensen, J. T. , & Grønkjær, P. (2012). Spatial variability of carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) stable isotope ratios in an Arctic marine food web. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 467, 47–59. 10.3354/meps09945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, K. A. , Ambrose, W. G. Jr , & Renaud, P. E. (1995). Sources of primary production, benthic‐pelagic coupling, and trophic relationships within the Northeast Water Polynya: Insights from δ13C and δ15N analysis. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 128, 1–10. 10.3354/meps128001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, K. A. , Fisk, A. , Karnovsky, N. , Holst, M. , Gagnon, J.‐M. , & Fortier, M. (2002). A stable isotope (δ13C, δ15N) model for the North Water food web: Implications for evaluating trophodynamics and the flow of energy and contaminants. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 49(22–23), 5131–5150. 10.1016/s0967-0645(02)00182-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh‐Guldberg, O. , & Bruno, J. F. (2010). The impact of climate change on the world's marine ecosystems. Science, 328(5985), 1523–1528. 10.1126/science.1189930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J. C. (2016). Tracing the origins, migrations, and other movements of fishes using stable isotopes. An Introduction to Fish Migration, 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R. M. , McClelland, J. W. , Tank, S. E. , Spencer, R. G. M. , & Shiklomanov, A. I. (2018). Arctic great rivers observatory. Water Quality Dataset, Version 20181010. Retrieved from https://www.arcticgreatrivers.org/data

- Iken, K. , Bluhm, B. , & Dunton, K. (2010). Benthic food‐web structure under differing water mass properties in the southern Chukchi Sea. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 57(1–2), 71–85. 10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iken, K. , Bluhm, B. , & Gradinger, R. (2005). Food web structure in the high Arctic Canada Basin: Evidence from δ13C and δ15N analysis. Polar Biology, 28(3), 238–249. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC . (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis In Stocker T. F., Qin D., Plattner G.‐K., Tignor M., Allen S. K., Boschung J., Nauels A., Xia Y., Bex V., & Midgley P. M. (Eds.), Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 255–316). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, M. , Lein, A. Y. , Zakharova, E. , & Savvichev, A. (2012). Carbon isotopic composition in suspended organic matter and bottom sediments of the East Arctic seas. Microbiology, 81(5), 596–605. 10.1134/S0026261712050086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. M. , Arp, C. D. , Jorgenson, M. T. , Hinkel, K. M. , Schmutz, J. A. , & Flint, P. L. (2009). Increase in the rate and uniformity of coastline erosion in Arctic Alaska. Geophysical Research Letters, 36(3). 10.1029/2008GL036205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, J. E. , & Sandquist, D. (1992). Carbon: Freshwater plants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 15(9), 1021–1035. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1992.tb01653.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Key, R. M. , Olsen, A. , van Heuven, S. , Lauvset, S. K. , Velo, A. , Lin, X. , Suzuki, T. (2015). Global ocean data analysis project, version 2 (GLODAPv2) [Miscellaneous]. 10.3334/CDIAC/OTG. NDP093_GLODAPv2, hdl:10013/epic.46499. [DOI]

- Kohlbach, D. , Graeve, M. , A. Lange, B. , David, C. , Peeken, I. , & Flores, H. (2016). The importance of ice algae‐produced carbon in the central Arctic Ocean ecosystem: Food web relationships revealed by lipid and stable isotope analyses. Limnology and Oceanography, 61(6), 2027–2044. 10.1002/lno.10351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kottek, M. , Grieser, J. , Beck, C. , Rudolf, B. , & Rubel, F. (2006). World map of the Köppen‐Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 15(3), 259–263. 10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuliński, K. , Kędra, M. , Legeżyńska, J. , Gluchowska, M. , & Zaborska, A. (2014). Particulate organic matter sinks and sources in high Arctic fjord. Journal of Marine Systems, 139, 27–37. 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2014.04.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyk, Z. Z. A. , Macdonald, R. W. , Tremblay, J.‐É. , & Stern, G. A. (2010). Elemental and stable isotopic constraints on river influence and patterns of nitrogen cycling and biological productivity in Hudson Bay. Continental Shelf Research, 30(2), 163–176. 10.1016/j.csr.2009.10.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, R. (2018). Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: Losses and coupled variability (1958–2018). Environmental Research Letters, 13(10), 105005 10.1088/1748-9326/aae3ec [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laidre, K. L. , Stirling, I. , Lowry, L. F. , Wiig, Ø. , Heide‐Jørgensen, M. P. , & Ferguson, S. H. (2008). Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate‐induced habitat change. Ecological Applications, 18(sp2). 10.1890/06-0546.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F. , Chen, M. , Tong, J. , Cao, J. , Qiu, Y. , & Zheng, M. (2014). Carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition of particulate organic matter and its biogeochemical implication in the Bering Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 33(12), 40–47. 10.1007/s13131-014-0570-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lind, S. , Ingvaldsen, R. B. , & Furevik, T. (2018). Arctic warming hotspot in the northern Barents Sea linked to declining sea‐ice import. Nature Climate Change, 8(7), 634 10.1038/s41558-018-0205-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbes, J. M. , Fitznar, H. P. , & Kattner, G. (2000). Biogeochemical characteristics of dissolved and particulate organic matter in Russian rivers entering the Arctic Ocean. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 64(17), 2973–2983. 10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00409-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovvorn, J. R. , Cooper, L. W. , Brooks, M. L. , De Ruyck, C. C. , Bump, J. K. , & Grebmeier, J. M. (2005). Organic matter pathways to zooplankton and benthos under pack ice in late winter and open water in late summer in the north‐central Bering Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 291, 135–150. 10.3354/meps291135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mars, J. , & Houseknecht, D. (2007). Quantitative remote sensing study indicates doubling of coastal erosion rate in past 50 yr along a segment of the Arctic coast of Alaska. Geology, 35(7), 583–586. 10.1130/G23672A.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, C. J. , & Ferguson, S. H. (2014). Validation of dentine deposition rates in beluga whales by interspecies cross dating of temporal δ13C trends in teeth. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 10 10.7557/3.3196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, K. W. , Hamady, L. L. , & Thorrold, S. R. (2013a). Ocean ecogeochemistry: A review. Oceanography and Marine Biology, 51, 327–373. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, K. W. , Hamady, L. L. , & Thorrold, S. R. (2013b). A review of ecogeochemistry approaches to estimating movements of marine animals. Limnology and Oceanography, 58(2), 697–714. 10.4319/lo.2013.58.2.0697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michener, R. H. , & Kaufman, L. (2007). Stable isotope ratios as tracers in marine food webs: An update. Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science, 2, 238–282. 10.1002/9780470691854.ch9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misarti, N. , Finney, B. , Maschner, H. , & Wooller, M. J. (2009). Changes in northeast Pacific marine ecosystems over the last 4500 years: Evidence from stable isotope analysis of bone collagen from archeological middens. The Holocene, 19(8), 1139–1151. 10.1177/0959683609345075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M. A. , Quakenbush, L. T. , Mahoney, B. A. , Taras, B. D. , & Wooller, M. J. (2018). Fifty years of Cook Inlet beluga whale feeding ecology from isotopes in bone and teeth. Endangered Species Research, 36, 77–87. 10.3354/esr00890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, S. D. , Clementz, M. T. , & Koch, P. L. (2010). Using stable isotope biogeochemistry to study marine mammal ecology. Marine Mammal Science, 26(3), 509–572. 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2009.00354.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, S. , Etnier, M. , Kurle, C. , Waldbauer, J. , Chamberlain, C. , & Koch, P. (2007). Historic decline in primary productivity in western Gulf of Alaska and eastern Bering Sea: Isotopic analysis of northern fur seal teeth. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 332, 211–224. 10.3354/meps332211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, M. , Macdonald, R. , Melling, H. , & Iseki, K. (2006). Particle fluxes and geochemistry on the Canadian Beaufort Shelf: Implications for sediment transport and deposition. Continental Shelf Research, 26(1), 41–81. 10.1016/j.csr.2005.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly, C. M. , Hecky, R. E. , Cohen, A. S. , & Plisnier, P.‐D. (2002). Interpreting stable isotopes in food webs: Recognizing the role of time averaging at different trophic levels. Limnology and Oceanography, 47(1), 306–309. 10.4319/lo.2002.47.1.0306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overland, J. E. , & Wang, M. (2010). Large‐scale atmospheric circulation changes are associated with the recent loss of Arctic sea ice. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography, 62(1), 1–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0870.2009.00421.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxtoby, L. , Budge, S. , Iken, K. , Brien, D. O. , & Wooller, M. (2016). Feeding ecologies of key bivalve and polychaete species in the Bering Sea as elucidated by fatty acid and compound‐specific stable isotope analyses. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 557, 161–175. 10.3354/meps11863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxtoby, L. , Horstmann, L. , Budge, S. , O'Brien, D. , Wang, S. , Schollmeier, T. , & Wooller, M. (2017). Resource partitioning between Pacific walruses and bearded seals in the Alaska Arctic and sub‐Arctic. Oecologia, 184(2), 385–398. 10.1007/s00442-017-3883-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T. , Webb, D. , Rokeby, B. , Lawrence, M. , Hopky, G. , & Chiperzak, D. (1989). Autotrophic and heterotrophic production in the Mackenzie River/Beaufort Sea estuary. Polar Biology, 9(4), 261–266. 10.1007/BF00263774 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polito, M. J. , Hinke, J. T. , Hart, T. , Santos, M. , Houghton, L. A. , & Thorrold, S. R. (2017). Stable isotope analyses of feather amino acids identify penguin migration strategies at ocean basin scales. Biology Letters, 13(8), 20170241 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay, P. , Sonnerup, R. , Westby, T. , Stutsman, J. , & McNichol, A. (2003). Changes in the 13C/12C of dissolved inorganic carbon in the ocean as a tracer of anthropogenic CO2 uptake. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 17(1). 10.1029/2001GB001817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rachold, V. , Grigoriev, M. N. , Are, F. E. , Solomon, S. , Reimnitz, E. , Kassens, H. , & Antonow, M. (2000). Coastal erosion vs riverine sediment discharge in the Arctic Shelf seas. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 89(3), 450–460. 10.1007/s005310000113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rau, G. H. , Riebesell, U. , & Wolf‐Gladrow, D. (1996). A model of photosynthetic 13C fractionation by marine phytoplankton based on diffusive molecular CO2 uptake. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 275–285. 10.3354/meps133275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rau, G. , Takahashi, T. , Des Marais, D. , Repeta, D. , & Martin, J. (1992). The relationship between δ13C of organic matter and [CO2 (aq)] in ocean surface water: Data from a JGOFS site in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and a model. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 56(3), 1413–1419. 10.1016/0016-7037(92)90073-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, V. , Iken, K. , Gosselin, M. , Tremblay, J.‐É. , Bélanger, S. , & Archambault, P. (2015). Benthic faunal assimilation pathways and depth‐related changes in food‐web structure across the Canadian Arctic. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 102, 55–71. 10.1016/j.dsr.2015.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabine, C. L. , Feely, R. A. , Gruber, N. , Key, R. M. , Lee, K. , Bullister, J. L. , … Tilbrook, B. (2004). The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 . Science, 305(5682), 367–371. 10.1126/science.1097403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakshaug, E. (2004). Primary and secondary production in the Arctic Seas In Stein R. & Macdonald R. W. (Eds.), The organic carbon cycle in the Arctic Ocean (pp. 57–81). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sarà, G. , Pirro, M. , Romano, C. , Rumolo, P. , Sprovieri, M. , & Mazzola, A. (2007). Sources of organic matter for intertidal consumers on Ascophyllum‐shores (SW Iceland): A multi‐stable isotope approach. Helgoland Marine Research, 61(4), 297–302. 10.1007/s10152-007-0078-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schell, D. M. (2000). Declining carrying capacity in the Bering Sea: Isotopic evidence from whale baleen. Limnology and Oceanography, 45(2), 459–462. 10.4319/lo.2000.45.2.0459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schell, D. M. (2001). Carbon isotope ratio variations in Bering Sea biota: The role of anthropogenic carbon dioxide. Limnology and Oceanography, 46(4), 999–1000. 10.4319/lo.2001.46.4.0999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schell, D. , Saupe, S. , & Haubenstock, N. (1989). Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) growth and feeding as estimated by δ13C techniques. Marine Biology, 103(4), 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Schlitzer, R. (2016). Ocean data view. Retrieved from http://odv.awi.de [Google Scholar]

- Schmittner, A. , Gruber, N. , Mix, A. , Key, R. , Tagliabue, A. , & Westberry, T. (2013). Biology and air–sea gas exchange controls on the distribution of carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) in the ocean. Biogeosciences, 10(9), 5793–5816. 10.5194/bg-10-5793-2013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, C. J. , & Calvert, S. E. (2001). Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of marine and terrestrial organic matter in Arctic Ocean sediments: Implications for nutrient utilization and organic matter composition. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 48(3), 789–810. 10.1016/S0967-0637(00)00069-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. L. , Henrichs, S. M. , & Rho, T. (2002). Stable C and N isotopic composition of sinking particles and zooplankton over the southeastern Bering Sea shelf. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 49(26), 6031–6050. 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00332-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Søreide, J. E. , Carroll, M. L. , Hop, H. , Ambrose, W. G. Jr , Hegseth, E. N. , & Falk‐Petersen, S. (2013). Sympagic‐pelagic‐benthic coupling in Arctic and Atlantic waters around Svalbard revealed by stable isotopic and fatty acid tracers. Marine Biology Research, 9(9), 831–850. 10.1080/17451000.2013.775457 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Søreide, J. E. , Falk‐Petersen, S. , Hegseth, E. N. , Hop, H. , Carroll, M. L. , Hobson, K. A. , & Blachowiak‐Samolyk, K. (2008). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios of suspended particulate organic matter in waters around Svalbard archipelago. PANGAEA. 10.1594/PANGAEA.786711. In supplement to: Søreide, JE et al. (2008): Seasonal feeding strategies of Calanus in the high‐Arctic Svalbard region. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 55(20-21), 2225-2244, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Søreide, J. E. , Hop, H. , Carroll, M. L. , Falk‐Petersen, S. , & Hegseth, E. N. (2006). Seasonal food web structures and sympagic–pelagic coupling in the European Arctic revealed by stable isotopes and a two‐source food web model. Progress in Oceanography, 71(1), 59–87. 10.1016/j.pocean.2006.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabue, A. , & Bopp, L. (2008). Towards understanding global variability in ocean carbon‐13. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 22 10.1029/2007GB003037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, T. , Sutherland, S. C. , Sweeney, C. , Poisson, A. , Metzl, N. , Tilbrook, B. , … Nojiri, Y. (2002). Global sea–air CO2 flux based on climatological surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 49(9–10), 1601–1622. 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00003-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamelander, T. , Reigstad, M. , Hop, H. , & Ratkova, T. (2009). Ice algal assemblages and vertical export of organic matter from sea ice in the Barents Sea and Nansen Basin (Arctic Ocean). Polar Biology, 32(9), 1261–1273. 10.1007/s00300-009-0622-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamelander, T. , Renaud, P. E. , Hop, H. , Carroll, M. L. , Ambrose, W. G. Jr , & Hobson, K. A. (2006). Trophic relationships and pelagic–benthic coupling during summer in the Barents Sea Marginal Ice Zone, revealed by stable carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 310, 33–46. 10.3354/meps310033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. N. , & Papadimitriou, S. (2011). Biogeochemistry of sea ice In Singh V. P., Singh P., & Haritashya U. K. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of snow, ice and glaciers (pp. 98–102). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M. K. , Kremer, C. T. , Klausmeier, C. A. , & Litchman, E. (2012). A global pattern of thermal adaptation in marine phytoplankton. Science, 338(6110), 1085–1088. 10.1126/science.1224836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, J.‐É. , & Gagnon, J. (2009). The effects of irradiance and nutrient supply on the productivity of Arctic waters: A perspective on climate change In Nihoul J. (Ed.), Influence of climate change on the changing arctic and sub‐arctic conditions (pp. 73–93). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, J.‐E. , Michel, C. , Hobson, K. A. , Gosselin, M. , & Price, N. M. (2006). Bloom dynamics in early opening waters of the Arctic Ocean. Limnology and Oceanography, 51(2), 900–912. 10.4319/lo.2006.51.2.0900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Zanden, M. J. , Clayton, M. K. , Moody, E. K. , Solomon, C. T. , & Weidel, B. C. (2015). Stable isotope turnover and half‐life in animal tissues: A literature synthesis. PLoS ONE, 10(1), e0116182 10.1371/journal.pone.0116182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaqué, D. , Lara, E. , Arrieta, J. M. , Holding, J. , Sà, E. L. , Hendriks, I. E. , … Duarte, C. M. (2019). Warming and CO2 enhance Arctic heterotrophic microbial activity. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 494 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela, D. E. , Crawford, D. W. , Wrohan, I. A. , Wyatt, S. N. , & Carmack, E. C. (2013). Pelagic primary productivity and upper ocean nutrient dynamics across Subarctic and Arctic Seas. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 118(12), 7132–7152. 10.1002/2013JC009211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet, M. , Richardson, T. L. , Metfies, K. , Nöthig, E.‐M. , & Peeken, I. (2017). Models of plankton community changes during a warm water anomaly in arctic waters show altered trophic pathways with minimal changes in carbon export. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 160 10.3389/fmars.2017.00160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. W. , Budge, S. M. , Gradinger, R. R. , Iken, K. , & Wooller, M. J. (2014). Fatty acid and stable isotope characteristics of sea ice and pelagic particulate organic matter in the Bering Sea: Tools for estimating sea ice algal contribution to Arctic food web production. Oecologia, 174(3), 699–712. 10.1007/s00442-013-2832-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. W. , Budge, S. M. , Iken, K. , Gradinger, R. R. , Springer, A. M. , & Wooller, M. J. (2015). Importance of sympagic production to Bering Sea zooplankton as revealed from fatty acid‐carbon stable isotope analyses. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 518, 31–50. 10.3354/meps11076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenaar, L. I. (2019). Introduction to conducting stable isotope measurements for animal migration studies In Viljoen G. J., Luckins A. G., & Naletoski I. (Eds.), Tracking animal migration with stable isotopes (pp. 25–51). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann, P. , Bauerfeind, E. , Fortier, M. , Fukuchi, M. , Hargrave, B. , Moran, B. , … Peinert, R. (2004). Particulate organic carbon flux to the Arctic Ocean sea floor In Stein R. & Macdonald R. W. (Eds.), The organic carbon cycle in the Arctic Ocean (pp. 101–138). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, A. , Kawamiya, M. , Ishida, A. , Yamanaka, Y. , & Watanabe, S. (2012). Impact of rapid sea‐ice reduction in the Arctic Ocean on the rate of ocean acidification. Biogeosciences, 9(6), 2365–2375. 10.5194/bg-9-2365-2012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. , Bruggeman, J. , Rickaby, R. , Erez, J. , & Conte, M. (2013). Evidence for changes in carbon isotopic fractionation by phytoplankton between 1960 and 2010. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 27(2), 505–515. 10.1002/gbc.20045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Quay, P. D. , & Wilbur, D. O. (1995). Carbon isotope fractionation during gas‐water exchange and dissolution of CO2 . Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 59(1), 107–114. 10.1016/0016-7037(95)91550-D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. , Chen, M. , Guo, L. , Gao, Z. , Ma, Q. , Cao, J. , … Li, Y. (2012). Variations in the isotopic composition of particulate organic carbon and their relation with carbon dynamics in the western Arctic Ocean. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 81, 72–78. 10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuur, A. , Ieno, E. N. , & Smith, G. M. (2007). Analyzing ecological data. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials