Abstract

Parent–child relationships change during adolescence. Furthermore, parents and adolescents perceive parenting differently. We examined the changes in perceptions of parental practices in fathers, mothers, and adolescents during adolescence. Furthermore, we investigated if fathers', mothers', and adolescents' perceptions converge during adolescence. Following 497 families across six waves (ages 13–18), we investigated the development of parental support and behavioral control using mother and father self‐reports, and adolescent reports for mothers and fathers. We found curvilinear decrease for support and control. Parent–adolescent convergence emerged over the 6 years: those with higher intercepts had a steeper decrease, whereas correlations among parent and adolescent reports increased. This multi‐informant study sheds light on the development of parent–adolescent convergence on perceptions of parenting.

Family relationships change during adolescence (Branje, Laursen, & Collins, 2012), even though contemporary research shows that adolescence is not necessarily a turbulent period. As adolescents start to strive for more autonomy, parents need to adapt their behavior and expectations to a more egalitarian relationship with their offspring (Smetana, 2011). Therefore, changes in how parents behave toward their adolescent children may be expected. During this developing process, differences arise in how parents and adolescents perceive their relationship (De Goede, Branje, & Meeus, 2009), as well as in what their expectations are regarding when autonomy should be attained (Deković, Noom, & Meeus, 1997). Despite these expected developmental changes, and the sporadic empirical evidence thereof, research on the development of parenting across adolescence remains scarce and has generally been based on adolescent reports. In this study, we investigated longitudinal changes in levels of parental support and parental behavioral control as perceived by fathers, mothers, and adolescents between ages 13 and 18 years. In addition, we examined the developmental changes in the extent to which fathers, mothers, and adolescents differ in their perceptions of parental support, and parental behavioral control. Investigating the development of perceptions from different perspectives is important, because research has shown that not only the perceptions of parenting themselves, but also parent–adolescent differences in perceptions of parenting, are related to the psychosocial adaptation of both parents and adolescents (Leung, Shek, & Li, 2016).

Parental Support and Parental Behavioral Control

Parenting is a broad construct that refers to what parents do to raise their children. It includes cognitions regarding children and child‐rearing, as well as behavior (see Bornstein, 2015; Smetana, 2017). Notwithstanding its breadth, parenting has been conceptualized as consisting of two broad dimensions: responsiveness and demandingness (Baumrind, 1968). In this study, we focused on these two core aspects of parenting, and we operationalized responsiveness and demandingness as parental support and parental behavioral control, respectively. Support means that parents show love, warmth, and acceptance for their children's personality and uniqueness. Behavioral control aims at shaping children's behavior by setting limits and rules regarding what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior (Baumrind, 2013). These two parenting dimensions are important aspects of child and adolescent socialization across cultural contexts, as has been shown by studies that linked them to several aspects of adolescent adjustment in different countries. For example, low support has been prospectively linked to internalizing and externalizing problems in the Netherlands (Branje et al., 2012), lower quality of peer relationships, and moral disengagement in the United States (Trentacosta et al., 2011). Meta‐analytic evidence shows that low parental support is among the strongest contributors to youth depression (Yap, Pilkington, Ryan, & Jorm, 2014). Similarly, control has been linked longitudinally to lower levels of both internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors of adolescents in China (Q. Wang, Pomerantz, & Chen, 2007), and too much behavioral control has been negatively linked to African American minority adolescent adjustment (Smetana, Crean, & Campione‐Barr, 2005). Therefore, this study focuses on the development of parental support and behavioral control.

Changes in parent–adolescent relationships have been described in many theoretical formulations, among which are psychoanalytical (Blos, 1967), evolutionary (Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991; Branje et al., 2012) and cognitive‐social cognitive (Laursen & Collins, 2009) theoretical perspectives (see Smetana, 2011, for an overview). Common in all these theoretical models is the hypothesis that adolescence is the period when family relationships change, and the hierarchical nature of the parent–child relationship gradually transforms to a more egalitarian and horizontal parent–adolescent relationship. Adolescence entails an increase in adolescent autonomy, which pushes for a decrease in behavioral control and curvilinear changes in support from parents. Hypothesized reasons for this increase in autonomy are the distancing of adolescents from parents in search of a constructed self (neo‐psychoanalytic approach), the preparation for adult‐like mature relationships (evolutionary perspective), and the increased cognitive abilities which allow more comparisons among different views (cognitive perspective). The expectancy violation–realignment model suggests that in parent–adolescent relationships, expectations for each other's behavior are more likely violated during stages of rapid change, like adolescence (Laursen & Collins, 2009). This violation first leads to conflicts, and then to a reevaluation of initial expectations. Additionally, the multiple biological, cognitive, and social changes that adolescents go through often happen at the same time that parents experience difficulties related to their own life stage, which may create coincidental crises (Steinberg & Silk, 2002), pushing for changes. Therefore, changes in parent–adolescent relationships and parenting may be expected, due to adolescents' strive for autonomy and the changing balance of the parent–child relationship from more hierarchical to more egalitarian. This strive may lead to decreases in support from early to middle adolescence, stability or increases thereafter, and a decrease in control throughout adolescence.

Several empirical studies have examined the development of parenting during adolescence (Meeus, 2016). Most longitudinal studies so far on the development of parental support have focused on the years between early and middle adolescence and revealed that there is a decrease in the degree to which parents offer support to their adolescents (Chen, Liu, & Li, 2000; Hafen & Laursen, 2009; McGue, Elkins, Walden, & Iacono, 2005; Trentacosta et al., 2011). The few longitudinal studies across adolescence showed that support develops in a curvilinear way, decreasing from early to middle adolescence, leveling off during middle to late adolescence, and tending to increase from late adolescence on (De Goede et al., 2009; Feinberg, McHale, Crouter, & Cumsille, 2003; Helsen, Vollebergh, & Meeus, 2000; Shanahan, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2007). Age 16 may be a turning point, where support stops decreasing (Shanahan et al., 2007). Thus, empirical studies are supportive of the idea that parental support decreases from early to middle adolescence and stabilizes thereafter, reflecting a curvilinear growth pattern.

Regarding control, most previous studies span 1–2 years, during early to middle adolescence (ages 12–16), and reveal contradictory results (Chen et al., 2000; Keijsers, Branje, VanderValk, & Meeus, 2010; Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, 2010; Shek, 2008; Q. Wang et al., 2007). Some studies showed a decline in control during early to middle adolescence (e.g., Chen et al., 2000; Keijsers et al., 2010; Kerr et al., 2010), whereas others showed no significant change (e.g., Q. Wang et al., 2007). Studies spanning a longer period showed that control decreases across adolescence, with a stronger decrease from middle adolescence onward (Keijsers, Frijns, Branje, & Meeus, 2009; Keijsers & Poulin, 2013). Beliefs about legitimacy of parental control also change; parents and adolescents believe that parental control becomes less legitimate during adolescence, according to adolescent and mother beliefs (Smetana, 2011; Smetana et al., 2005). Therefore, empirical studies offer some support to the theoretical proposition that behavioral control decreases across adolescence.

Gender Differences in Parenting

Parenting in adolescence may differ depending on the parents' and adolescents' gender. Mothers and fathers are thought to serve different roles in the family. Fathers compared to mothers are thought to play a more central role in gender socialization and gender typing. They promote masculinity in boys and femininity in girls, because they differentiate between boys and girls more, and they are thought to transmit social norms and expectations (Johnson, 1975). This is true especially during adolescence because of the emergence of puberty and sexuality, as well as the increase in independence (Collins & Russell, 1991). Mothers' parenting is more consistent, as it is less affected by contextual conditions than fathers' parenting, possibly because the maternal role is thought to be more socially scripted than the paternal role. For example, working conditions of mothers and fathers have been found to be relatively unrelated to maternal parenting, but they relate to paternal parenting (e.g., Crouter, Helms‐Erikson, Updegraff, & McHale, 1999; Davis, Crouter, & McHale, 2006). Therefore, differences between mothering and fathering can be expected (e.g., Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, 2005); these differences may be rooted in socially constructed roles (Dufur, Howell, Downey, Ainsworth, & Lapray, 2010).

Furthermore, parents are thought to respond differently to their sons and daughters, promoting more autonomy in boys compared to girls. The gender intensification hypothesis posits that during adolescence, gender differences increase and same‐gender parent–adolescent dyads become (even more) different from opposite‐gender parent–adolescent dyads (Hill & Lynch, 1983). Moreover, the reciprocal role theory suggests that fathers will promote independence in boys and warmth in girls (Siegal, 1987). Factors like the family structure may influence how mothers and fathers differentiate between boys and girls. For example, birth order was found to be related to the longitudinal changes of time spent with mothers and fathers during adolescence (Lam, McHale, & Crouter, 2012). Although time spent with parents in the presence of other people declined throughout adolescence, the decline was stronger for first‐born compared to second‐born adolescents. Despite moderating factors like these, fathers can be expected to differentiate more among boys and girls than mothers do. Thus, differences in the development of support and control can be expected for both parents' and adolescents' gender, as well as the gender constellations of the dyads (i.e., mother–son, mother–daughter, father–son, father–daughter; Russell & Saebel, 1997).

Empirical studies on the development of support and control that studied mothers and fathers separately are lacking. When adolescent reports are used they most often refer either to mother alone (e.g., Trentacosta et al., 2011) or to parents in general (Q. Wang et al., 2007), missing how adolescents may perceive their mothers and fathers differently. Similarly, when parent reports are used, they usually include mothers (e.g., Hafen & Laursen, 2009), therefore missing fathers' perspectives on parenting. Studies that have used reports for mothers and fathers have shown that mothers were more supportive than fathers during adolescence, although the development of support did not differ between them (De Goede et al., 2009; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Mother–father differences in behavioral control have been reported as well, although the direction of this difference remains unclear (Keijsers et al., 2009; Shek, 2008). Again, the development of behavioral control did not differ between mothers and fathers (Keijsers et al., 2009).

Concerning adolescent gender, girls report higher mean levels of support than boys (De Goede et al., 2009; McGue et al., 2005), but studies are rather inconsistent in how support develops for boys and girls. Even though both girls and boys show a decrease in parental support during early adolescence, it is not clear whether this decrease follows the same rate for boys and girls (De Goede et al., 2009; McGue et al., 2005). Inconsistency is also found regarding gender differences in the case of behavioral control. Boys report lower levels of control than girls in some studies (Keijsers & Poulin, 2013; Shek, 2007), but higher levels of control than girls in other studies (Chen et al., 2000). No gender differences in the change in control were found in these studies.

To summarize, although the development of parenting is expected to differ between mothers and fathers, and between girls and boys, with mothers and girls showing higher support and control, longitudinal evidence for these hypotheses is limited.

Parent–Adolescent Divergence

It is not only mothers and fathers who may differ in their views of parenting, but adolescents may also have different views than their parents, consisting in part of different expectations regarding the timing of developmental tasks (Deković et al., 1997). Adolescents expect that they will attain several developmental tasks earlier than their parents think they will. For example, adolescents expect to be allowed to spend time unsupervised (e.g., going on vacation without parents, or staying home alone) at a younger age than parents expect. These differences in expectations are related to parent–adolescent conflicts (Deković et al., 1997).

Developmental perspectives (Branje et al., 2012; Smetana, 2011; Steinberg & Silk, 2002) suggest that parent–adolescent divergence in views is part of normative development: adolescents start to claim more autonomy than they had during childhood, while at the same time parents (typically in their midlife) have to release part of their authority and find new ways of relating to their offspring. This view leads to the expectation that parent–adolescent divergence is high in early adolescence and declines thereafter, as the relationship reaches a new, more egalitarian balance (for an overview see Smetana, 2011). Furthermore, the intergenerational stake hypothesis emphasizes the generational gap as an important factor in this divergence. Specifically, this hypothesis posits that differences in views among parents and adolescents emerge because of the differences in significance these relationships have for the people involved (Birditt, Hartnett, Fingerman, Zarit, & Antonucci, 2015). Parents are expected to psychologically invest more, and experience a higher quality in their relationship with their children than children do in their relationship with their parents. For example, parents have been found to be more supportive toward children than children are toward parents (Branje, van Aken, & van Lieshout, 2002). Regarding differences between parents and adolescents in parental control, studies have shown that parents and adolescents differ the most during early adolescence, and become more similar as they approach late adolescence in what regard control over issues has to do with time spent outside home, choice of friends, and the like (for an overview see Smetana, 2011; Smetana et al., 2005).

The Present Study

In this study, we aim to investigate how parenting, conceptualized as support and behavioral control, develops throughout adolescence, using reports from both mothers and fathers, as well as adolescent reports on the parenting of both mothers and fathers. By doing this, we extend previous literature on parenting in a number of ways. First, we investigate the trajectories of both parental support and behavioral control, offering a broader picture of how parenting develops. We expect that support will show curvilinear changes throughout adolescence, decreasing between early and middle adolescence, and either stabilizing or even increasing thereafter. Behavioral control is expected to show decreasing trajectories, but no specific hypotheses can be made regarding the form of its development. Second, we use four different reports for parental support and for parental behavioral control (mother for adolescent, father for adolescent, adolescent for mother, adolescent for father), extending, therefore, the parent–adolescent relationship literature. Based on previous results, we expect that mothers and fathers will differ at the mean level on both support and behavioral control, but not on the trajectories they will follow. Same‐gender parent–adolescent dyads are expected to become more similar than opposite‐gender parent–adolescent dyads. Finally, by including these four different reports, our third aim is to shed light on the development of parent–adolescent divergence in views. This is important, because we know little about how they develop during adolescence. Knowledge about the development of the views of parenting from different family members can be useful for the design and implementations of family interventions. We expect that adolescents will report less support and less control than parents, based on the finding that adolescents expect to attain autonomy at an earlier age than parents do (Deković et al., 1997). Parent–adolescent views are expected to converge during adolescence, as adolescents gain more real‐life experience with attaining developmental tasks. In sum, this study aims at investigating how parent–adolescent relationships develop during the course of adolescence.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 497 adolescents (43.1% girls, M age = 13.03, SD = 0.46, at T1; M age = 18.03, SD = 0.46, at T6), their mothers (N = 497, M age = 44.41, SD = 4.45, at T1; M age = 49.40, SD = 4.45, at T6), and their fathers (N = 456, M age = 46.74, SD = 5.10, at T1; M age = 51.68, SD = 5.11, at T6) who took part in six yearly waves of an ongoing longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Adolescents were recruited from randomly selected elementary schools from the province of Utrecht as well as from three other big cities in the Netherlands. From a list of 850 regular schools in the western and central regions of the Netherlands, 429 were randomly selected and approached. Of those, 296 (69%) were willing to participate, and 230 of those were approached. Schools were used for an initial screening (teacher reports for all 12‐year‐old students), as well as a means to approach families. Of the total number of students screened (n = 4,615), 1,544 were randomly selected. Because the aim of the study was to include two‐parent families with at least one more child older than 10 years old, 1,081 families were approached. Of those, 470 refused to take part and 114 did not provide informed consent, resulting in the final sample of 497 families. Data were collected via home visits. During the first measurement wave, adolescents were in first grade of high school. Most adolescents were native Dutch (94.8%), lived with both parents (85.2%), and came from families classified as medium or high socioeconomic status (SES; 87.7%). Regarding parents' level of education, most mothers and fathers had finished at least secondary school (primary or less: 3.9% mothers and 2.4% fathers; secondary school: 55.9% mothers and 48.1% fathers; higher education: 40.2% mothers and 49.6% fathers).

Measures

Support

We used the Support subscale of the Network of Relationships Inventory – Short Form (De Goede et al., 2009; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). The main interest of this study is to compare perceptions of parents and adolescents of parental support. This comparison is only possible if parents and adolescents report about the same thing. The full scale contained eight items, three of which change person of reference in the different reporter versions. For example, one of these items asks adolescents, “How much does your mother/father appreciate the things you do?” whereas the parent version asks, “How much does your child appreciate the things you do?” Three items were excluded. Thus, we included the following five items: “How much [do you/does your mother/father] treat [your child/you] like [(s)he is/you're] admired and respected?”; “How sure are you that this relationship will last no matter what?”; “How much do you play around and have fun with your [mother/father/child]?”; How much [do you/does your mother/father] really care about [your child/you]?”; “How much [do you/does your child] care about [your mother/father/you]?”. These items were answered on a 5‐point likert scale, ranging from 1 (little or not at all) to 5 (more is not possible). Adolescents completed the scale regarding the relationship with their mother (adolescent–mother/AM report) and their fathers (adolescent–father/AF report); both mothers and fathers completed the scale regarding the relationship with the adolescents (mother–adolescent/MA report and father–adolescent/FA report, respectively). The internal consistency of the scale was good for all informants and all waves, with Cronbach's alpha ranging between .77 and .84 for the AM report, between .82 and .88 for the AF report, between .72 and .79 for the MA report, and between .77 and .81 for the FA report.

Behavioral control

We used the scale developed by Kerr and Stattin (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). This subscale consists of five items, which are answered on a 5‐point likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always). It measures the degree to which parents establish rules regarding the adolescent's whereabouts. Adolescents reported the control they perceived from their mother and their father, and both mothers and fathers reported on the control they exert over their adolescents' behavior. The five items of the adolescent‐reported versions are as follows: “Do you need to have your mom's/dad's permission to stay out late on a weekday evening?”; “Do you need to ask your mother/father before you can decide with your friends what you will do on a Saturday evening?”; “If you have been out very late one night, does your mother/father require that you explain what you did and whom you were with?”; “Does your mother/father always require that you tell them where you are at night, who you are with, and what you do together?”; and “Before you go out on a Saturday night, does your mother/father require you to tell them where you are going and with whom?”. Internal consistency of the scales was high and Cronbach's αs across six waves ranged between .84 and .91 for the AM report, between .83 and .87 for the AF report, between .82 and .89 for the MA report, and between .84 and .88 for the FA report.

Attrition and Missing Values

The majority of adolescents (85.7%), mothers (84.5%), and fathers (75.5%) were still involved in the study at Wave 6, and the average participation rate across the six waves was 90.4%, 90.2%, and 81.7% for the adolescents, the mothers, and the fathers, respectively. Although Little's missing completely at random (MCAR) test (Little, 1988) was significant (χ2 (6118) = 7,121, p = .000), the normed χ2 of 1.16 indicated that the assumption of missingness being completely at random was not seriously violated. Therefore, data from all 497 families could be included in the analyses using a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998) to cope with missing data.

Procedure

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Utrecht University. Parents were required to provide informed consent. Adolescents and parents filled out questionnaires during annual home visits. Trained research assistants provided verbal instructions in addition to written instructions that accompanied the questionnaires. Confidentiality was guaranteed and the data were processed anonymously. At each wave, families received 100 euros for their participation.

Analytic Plan

First, to answer our research question regarding the development of parental support and behavioral control according to the different informants, we modeled the longitudinal development of parental support and behavioral control as reported by mothers, fathers, and adolescents with regard to both mothers and fathers using latent growth modeling (LGM; J. Wang & Wang, 2012). Four separate univariate LGMs, one per reporter, were conducted for each of the two variables. We determined the shape of the slope by testing whether linear or quadratic change would capture the development best. In the case of quadratic development, we tested whether piecewise change (two linear slopes; J. Wang & Wang, 2012), described the development equally well, as shown by the fit indices (comparative fit index [CFI], Tucker‐Lewis index [TLI], root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA], standardized root mean square residual [SRMR]). Using a piecewise model with two linear slopes allowed us to investigate potential differences in the development between early to middle and middle to late adolescence (e.g., Keijsers & Poulin, 2013; Shanahan et al., 2007). In the case of the piecewise LGM, we tested different time points as knots (the time of measurement where the two linear slopes could be split). To test whether adolescent gender moderated growth in support and control, we used a multiple group approach, and compared intercept and slope means of boys and girls using Wald tests.

To answer the research question regarding convergence in the development of parental support and behavioral control between pairs of informants, we ran a series of multivariate LGMs (eight models in total) in which the growth of parental support and behavioral control was modeled for each pair (e.g., the LGM of the adolescent–mother report of control was modeled together with the mother–adolescent report of control). To investigate reporter differences, we then computed a series of Wald tests to test for differences in means of the intercepts and slopes among the dyads (adolescent vs. father, adolescent vs. mother, father vs. mother), a technique that has been applied by Van Lissa et al. (2015). Again, a multiple group approach was used to test for gender differences. Soci‐economic status was used as a control variable in univariate and multivariate LGMs. Finally, as an additional analysis to answer this question, we also calculated the bivariate correlations between pairs of informants for each wave separately, to see how correlations change with age.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics (means and SDs) of the observed variables in Waves 1–6.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Observed Variables

| Age 13 (W1) | Age 14 (W2) | Age 15 (W3) | Age 16 (W4) | Age 17 (W5) | Age 18 (W6) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Support | ||||||||||||

| AM | 4.28 | 0.52 | 4.20 | 0.60 | 4.09 | 0.63 | 4.00 | 0.66 | 4.00 | 0.65 | 3.94 | 0.69 |

| AF | 4.03 | 0.62 | 3.93 | 0.67 | 3.84 | 0.70 | 3.76 | 0.72 | 3.73 | 0.79 | 3.68 | 0.78 |

| MA | 3.91 | 0.48 | 3.83 | 0.48 | 3.85 | 0.48 | 3.84 | 0.50 | 3.80 | 0.52 | 3.82 | 0.53 |

| FA | 3.64 | 0.52 | 3.61 | 0.55 | 3.62 | 0.53 | 3.58 | 0.52 | 3.58 | 0.54 | 3.57 | 0.58 |

| Control | ||||||||||||

| AM | 3.73 | 1.00 | 3.59 | 1.01 | 3.39 | 1.03 | 3.27 | 1.09 | 2.90 | 1.14 | 2.58 | 1.15 |

| AF | 3.37 | 1.06 | 3.17 | 1.07 | 3.02 | 1.04 | 2.89 | 1.05 | 2.64 | 1.05 | 2.28 | 1.00 |

| MA | 4.58 | 0.76 | 4.41 | 0.81 | 4.16 | 0.94 | 3.83 | 1.06 | 3.31 | 1.12 | 2.84 | 1.11 |

| FA | 4.31 | 0.86 | 4.20 | 0.89 | 3.96 | 0.94 | 3.68 | 1.02 | 3.22 | 1.06 | 2.77 | 1.03 |

AM: adolescent report for mother; AF: adolescent report for father; MA: mother report for adolescent; FA: father report for adolescent.

Because the meaning of parenting may change during development, we investigated the longitudinal measurement invariance of parental support and parental behavioral control for each reporter (eight models in total, analyzed in Mplus 7.11) before proceeding to the univariate LGMs. Seven out of eight models were configural, metric, and scalar longitudinally invariant, based on comparisons using several fit indices (Δχ2, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR). The only exception was the model regarding mothers' behavioral control. For this model, configural and metric invariance was achieved, but for scalar invariance to show an insignificant drop in fit, the intercept of one item had to be released for Wave 5 and Wave 6 (see Table in Appendix S1, online Supporting Information). Given that this represents a small part of this model, and also in order to allow comparability with other studies using the same scale, we decided not to leave this item out of the scale mean for any wave.

Longitudinal Development of Parental Support and Behavioral Control

In order to examine the first research question, regarding the trajectories of parental support and behavioral control, we first investigated the patterns of change in parental support and behavioral control. Then, we applied univariate LGMs to see how levels of parental support and behavioral control change across adolescence. Table 2 presents the fit indices of models with different forms of longitudinal change. For both support and behavioral control, quadratic change provided a better fit to the data than linear change. Furthermore, piecewise (two slopes split at age 16) and quadratic modeling provided similar fit. Age 16 was chosen as the best time point to separate the two linear slopes, both on empirical grounds, because we compared models with knots on different time points (ages 14, 15, 16, and 17)1, as well as on theoretical grounds, because we wanted to differentiate between early/middle and middle/late adolescence (see also Shanahan et al., 2007). Therefore, in the following analyses, we applied piecewise LGMs using age 16 as the point to separate the two linear slopes.

Table 2.

Fit Indices of Latent Growth Models With Linear, Piecewise (Set on Wave 4, Age 16), and Quadratic Slopes

| χ2 | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Piecewise | Quad. | Linear | Piecewise | Quad. | Linear | Piecewise | Quad. | Linear | Piecewise | Quad. | Linear | Piecewise | Quad. | Linear | Piecewise | Quad. | |

| Support | ||||||||||||||||||

| AM | 84.4 | 28.7 | 27.6 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .945 | .987 | .987 | .949 | .985 | .984 | .093 | .049 | .041 | .172 | .083 | .037 |

| AF | 90.4 | 24.8 | 16.6 | .00 | .02 | .16 | .947 | .992 | .997 | .950 | .990 | .996 | .098 | .043 | .028 | .139 | .084 | .034 |

| MA | 54.4 | 40.8 | 37.3 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .977 | .983 | .985 | .978 | .981 | .981 | .070 | .066 | .065 | .090 | .066 | .063 |

| FA | 38.0 | 29.1 | 25.0 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .987 | .991 | .993 | .988 | .989 | .991 | .055 | .052 | .049 | .055 | .090 | .031 |

| Control | ||||||||||||||||||

| AM | 65.5 | 17.4 | 15.9 | .00 | .19 | .20 | .934 | .994 | .995 | .938 | .993 | .994 | .080 | .026 | .026 | .058 | .036 | .028 |

| AF | 86.1 | 35.7 | 21.8 | .00 | .00 | .04 | .916 | .973 | .988 | .922 | .969 | .985 | .096 | .060 | .041 | .092 | .049 | .029 |

| MA | 168.6 | 31.6 | 21.2 | .00 | .00 | .05 | .857 | .983 | .991 | .866 | .980 | .989 | .139 | .054 | .039 | .098 | .039 | .044 |

| FA | 125.0 | 23.4 | 14.8 | .00 | .04 | .25 | .886 | .989 | .997 | .894 | .988 | .996 | .122 | .042 | .023 | .078 | .060 | .058 |

AM: adolescent report for mother; AF: adolescent report for father; MA: mother report for adolescent; FA: father report for adolescent.

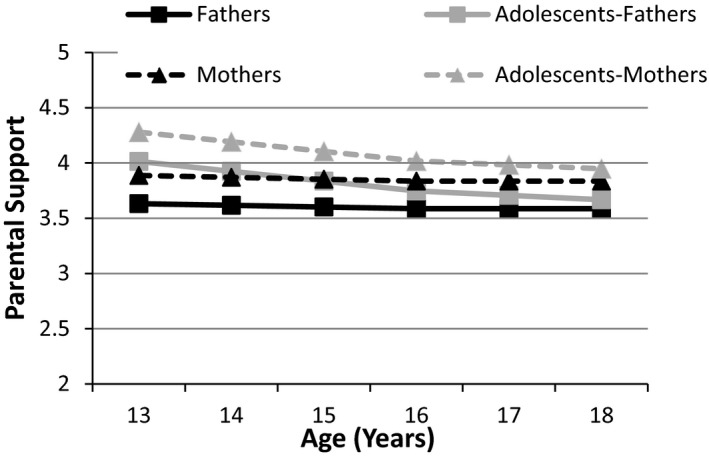

Parental support

The growth parameters of the univariate LGMs for parental support for all informants, by adolescent gender, are shown in Table 3 (also see Figure 1). For all informants, no adolescent gender differences were found in mean levels (intercepts), and the rate of change between ages 13 and 16 (slope 1) as well as between ages 16 and 18 (slope 2). It is worth noting that during the review process analyses were rerun controlling for SES. This led to very small changes in the parameters, but the few gender differences in slopes that were initially found did not reach significance any more.2

Table 3.

Growth Parameters of Multigroup Univariate Latent Growth Models, Controlling for Family SES

| Intercept | Slope 1 | Slope 2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance | |||||||

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| Support | ||||||||||||

| AM | 4.27*** | 4.31*** | 0.14*** | 0.18*** | −0.10*** | −0.06*** | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | −0.05** | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| AF | 4.06*** | 3.99*** | 0.21*** | 0.27*** | −0.09*** | −0.09*** | 0.02*** | 0.04*** | −0.05* | 0.00 | 0.06*** | 0.05** |

| MA | 3.87*** | 3.91*** | 0.14*** | 0.14*** | −0.03*** | 0.00 | 0.01** | 0.005** | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01* | 0.02* |

| FA | 3.65*** | 3.62*** | 0.19*** | 0.18*** | −0.03** | −0.00 | 0.05* | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02** |

| Control | ||||||||||||

| AM | 3.68*** | 3.73*** | 0.33*** | 0.42*** | −0.20a *** | −0.11b *** | 0.03** | 0.05*** | −0.31*** | −0.35*** | 0.12** | 0.15** |

| AF | 3.36*** | 3.28*** | 0.46*** | 0.45*** | −0.19a *** | −0.09b ** | 0.03** | 0.04*** | −0.29*** | −0.33*** | 0.10** | 0.14** |

| MA | 4.62*** | 4.60*** | 0.22*** | 0.25*** | −0.26*** | −0.24*** | 0.07*** | 0.07*** | −0.50*** | −0.53*** | 0.15*** | 0.12*** |

| FA | 4.33*** | 4.43*** | 0.38*** | 0.32*** | −0.21*** | −0.22*** | 0.04*** | 0.03*** | −0.52*** | −0.44*** | 0.11*** | 0.10** |

SES: socioeconomic status; AM: adolescent report for mother; AF: adolescent report for father; MA: mother report for adolescent; FA: father report for adolescent. Subscripts a, b indicate significant gender differences.

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Latent growth models of father, mother, adolescent–father, and adolescent–mother reports of support, T1‐T6.

Adolescent reports

Between ages 13 and 16, support from both mother and father decreased significantly according to both boys and girls. Between ages 16 and 18, only boys reported a decrease in support from mothers and fathers, but this gender difference was not significant according to the Wald tests.

Parent reports

Although the coefficients regarding the trajectory of mother‐ and father‐reported support were different for boys and girls, these differences did not reach significance. For girls, according to both mothers and fathers, support remained stable throughout adolescence. For boys, both mothers and fathers reported a significant decrease between ages 13 and 16, and stability thereafter.

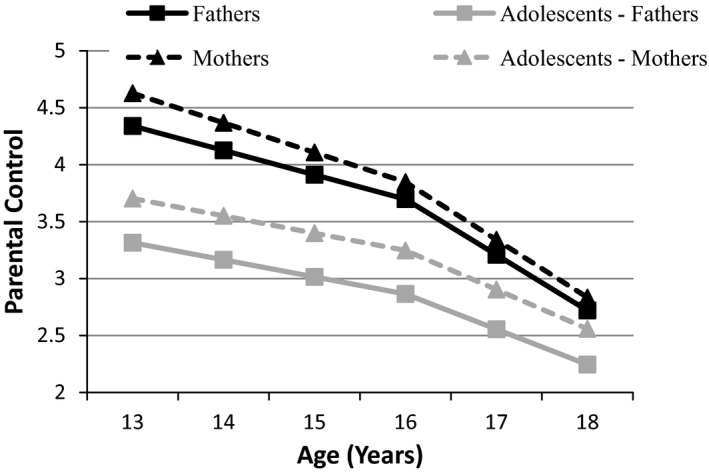

Behavioral control

The growth parameters of the univariate LGMs for control for all informants, by adolescent gender, are shown in Table 3 (also see Figure 2). According to all informants, control decreased from age 13 to age 16, and then declined more between ages 16 and 18. No gender differences were found in mean levels of control, but the rate of change differed between boys and girls according to adolescent reports.

Figure 2.

Latent growth models of father, mother, adolescent–father, and adolescent–mother reports of control, T1‐T6.

Adolescent reports

From age 13 to 16, boys reported a significantly stronger decrease in control from both mothers [χ2 Wald (1) = 7.20, p = .007] and fathers [χ2 Wald (1) = 10.00, p = .002], than girls did. Between ages 16 and 18, however, the decrease in adolescent‐reported control from mothers and fathers was the same for boys and girls.

Parent reports

From age 13 to age 16, as well as from age 16 to age 18, mothers and fathers reported a significant decline in control, which did not differ statistically between boys and girls.

Summing up, results showed that across all informants, parental support and parental behavioral control decrease during adolescence. Parental support only decreased in early to middle adolescence and remained stable thereafter, whereas parental behavioral control decreased throughout adolescence, with the decline being more pronounced from middle adolescence onward. Few gender differences emerged in these patterns.

Convergence in Adolescent and Parental Views of Parental Support and Behavioral Control

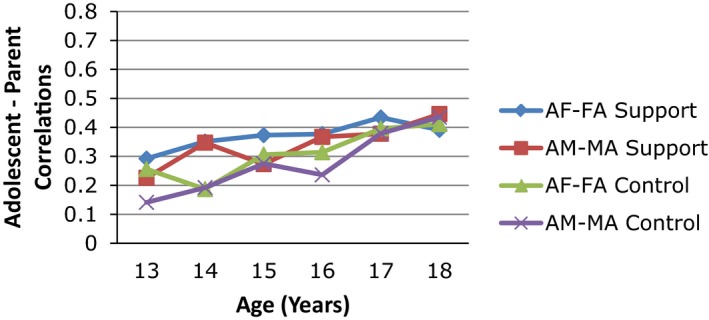

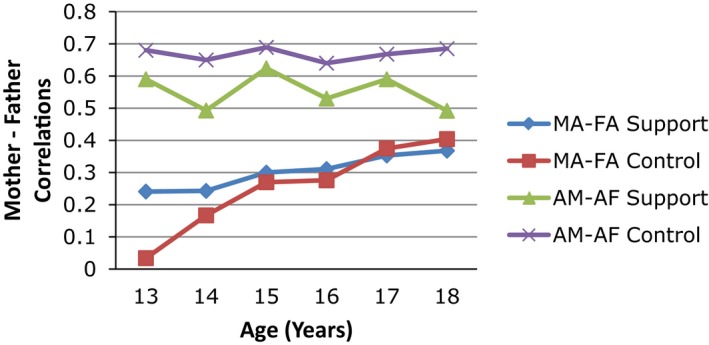

In order to examine the second research question regarding the development of convergence in perceptions of parental support and behavioral control across informants, we conducted multivariate LGMs, conducting Wald test comparisons of means. Results of the Wald comparisons for development of parental support and behavioral control as perceived by fathers versus mothers and parents versus adolescents are shown in Table 4. Bivariate correlations between informants, for each wave separately are shown in Table 5 (see also Figures 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Means of Multivariate Latent Growth Parameters and Wald Comparisons Among Informants, Controlling for Family SES

| Intercept | Slope 1 | Slope 2 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |||||||||||||

| Means | χ2 Wald | p | Means | χ2 Wald | p | Means | χ2 Wald | p | Means | χ2 Wald | p | Means | χ2 Wald | p | Means | χ2 Wald | p | |

| Support | ||||||||||||||||||

| Reporter differences | ||||||||||||||||||

| AM–MA | 4.27/3.87 | 121 | .00 | 4.31/3.91 | 82.7 | .00 | −0.10/−0.03 | 25.0 | .00 | −0.06/0.00 | 11.5 | .00 | −0.05/0.00 | 6.78 | .01 | −0.02/0.00 | 0.55 | .46 |

| AF–FA | 4.05/3.65 | 95.4 | .00 | 3.99/3.62 | 56.6 | .00 | −0.09/−0.02 | 15.1 | .00 | −0.08/0.00 | 15.8 | .00 | −0.05/0.00 | 3.98 | .05 | 0.00/0.00 | 0.04 | .83 |

| Parental differences | ||||||||||||||||||

| MA–FA | 3.87/3.65 | 38.6 | .00 | 3.91/3.62 | 38.3 | .00 | −0.03/−0.02 | 0.06 | .80 | 0.00/0.00 | 0.19 | .67 | 0.00/0.00 | 0.18 | .68 | −0.00/0.00 | 0.00 | .99 |

| AM–AF | 4.27/4.05 | 62.0 | .00 | 4.31/3.99 | 47.1 | .00 | −0.10/−0.09 | 1.75 | .19 | −0.06/−0.08 | 2.12 | .14 | −0.05/−0.05 | 0.05 | .82 | −0.02/0.00 | 0.20 | .66 |

| Control | ||||||||||||||||||

| Reporter differences | ||||||||||||||||||

| AM–MA | 3.66/4.63 | 147 | .00 | 3.74/4.59 | 102 | .00 | −0.19/−0.26 | 3.39 | .06 | −0.11/−0.24 | 9.69 | .00 | −0.32/−0.50 | 19.93 | .00 | −0.35/−0.53 | 14.3 | .00 |

| AF–FA | 3.35/4.32 | 137 | .00 | 3.28/4.43 | 158 | .00 | −0.18/−0.21 | 0.44 | .50 | −0.09/−0.22 | 11.5 | .00 | −0.29/−0.52 | 32.9 | .00 | −0.34/−0.45 | 5.86 | .02 |

| Parental differences | ||||||||||||||||||

| MA–FA | 4.62/4.32 | 19.9 | .00 | 4.59/4.43 | 4.71 | .03 | −0.26/−0.21 | 3.08 | .08 | −0.24/−0.22 | 0.17 | .67 | −0.50/−0.53 | 0.38 | .54 | −0.53/−0.45 | 3.74 | .05 |

| AM–AF | 3.64/3.36 | 27.2 | .00 | 3.73/3.32 | 44.4 | .00 | −0.18/−0.18 | 0.00 | .97 | −0.11/−0.11 | 0.03 | .86 | −0.32/−0.29 | 1.10 | .30 | −0.35/−0.33 | 0.20 | .65 |

SES: socioeconomic status; AM: Adolescent report for mother; AF: Adolescent report for father; MA: Mother report for adolescent; FA: Father report for adolescent.

Table 5.

Bivariate Correlations Among Informants for Waves 1–6

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | W6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | ||||||

| Reporter differences | ||||||

| AM‐MA | .226a | .347b,c | .273a,b | .367c,d | .378c,d | .446d |

| AF‐FA | .292a | .351a,b | .373a,b | .377a,b | .434b | .391b |

| Parental differences | ||||||

| MA‐FA | .241a | .243a | .300a,b | .311a,b | .353b | .368b |

| AM‐AF | .590b | .493a | .624b | .530a,b | .590b | .492a |

| Control | ||||||

| Reporter differences | ||||||

| AM‐MA | .141a | .192a,b | .275b | .236a,b | .379c | .435c |

| AF‐FA | .256a | .187a | .306a,b | .314a,b | .396b,c | .411c |

| Parental differences | ||||||

| MA‐FA | .034* a | .167b | .270c | .276c | .375d | .404d |

| AM‐AF | .680a | .650a | .689a | .640a | .668a | .685a |

AM: adolescent report for mother; MA: mother report for adolescent; AF: adolescent report for father; FA: father report for adolescent. Correlations with same subscripts within each row do not differ statistically.

*All correlations, except for this, are significant, p < .001. N = 497.

Figure 3.

Bivariate correlations among adolescent and parent reports of support and control, for each wave separately. Note. AM: adolescent–mother; AF: adolescent–father; MA: mother–adolescent; FA: father–adolescent.

Figure 4.

Bivariate correlations among reports for mother and father support and control, for each wave separately. Note. AM: adolescent–mother; AF: adolescent–father; MA: mother–adolescent; FA: father–adolescent.

Parental support

Parental differences

Mothers showed a higher mean level of support than fathers, according to both parent and adolescent reports. Regarding change, support declined at the same rate for mothers and fathers both between ages 13 and 16, and between ages 16 and 18. Bivariate correlations increased significantly from age 13 to age 18, for parent reports only.

Reporter differences

Adolescents (both boys and girls) reported higher mean levels of support from mothers and from fathers. Regarding change, adolescents reported a stronger decrease in support from age 13 to age 16 than both mothers and fathers; thus adolescent reports converged with parent reports over time. Between ages 16 and 18, boys perceived a significant drop in maternal support, whereas mothers did not report significant change in support during this period. For both the adolescent–mother and the adolescent–father relationships, bivariate correlations increased significantly from age 13 to age 18. Specifically, shared variance (r 2) increased from 5% (adolescent‐mother relationship) and 8.5% (adolescent‐father relationship) at age 13, to 20% and 15%, respectively, at age 18.

Behavioral control

Parental differences

Mothers showed higher mean levels of behavioral control according to both parent and adolescent reports. Change in behavioral control during both ages 13 to 16, and ages 16 to 18 was the same for mothers and fathers according to both boys and girls. Between ages 16 and 18, mothers, as compared to fathers, reported a significantly stronger decline in the control they showed toward adolescent girls. Bivariate correlations between paternal and maternal reports also increased significantly from ages 13 to 18, indicating converging parental views, but bivariate correlations between adolescents' reports about mothers and fathers were stable and high across adolescence.

Reporter differences

Parents of both boys and girls reported higher mean levels of behavioral control than adolescents. Regarding change, parents showed a stronger decrease in control than adolescents, resulting in converging views. From age 13 to age 16 mothers reported a stronger decrease in control than adolescents did; fathers reported a stronger decrease only for girls. Between ages 16 and 18, mothers and fathers reported a stronger decrease than adolescents. This shows that the timing of convergence in control between adolescents and fathers is different for boys and girls. For both the adolescent–mother and the adolescent–father relationships, bivariate correlations between parent and adolescent reports increased significantly from age 13 to age 18. Specifically, shared variance (r 2) increased from 2% (adolescent‐mother relationship) and 6.5% (adolescent‐father relationship) at age 13, to 19% and 17%, respectively, at age 18.

Summing up, the results of the second series of analyses suggest increasing convergence between parents and adolescents in their reports of parental support and parental behavioral control. More specifically, in both support and behavioral control, a general picture emerged in which those who reported the higher mean levels on either support (adolescents higher intercept than parents) or behavioral control (parents higher intercept than adolescents), also showed the steeper decrease during the course of adolescence, resulting, thus, in converging views. This conclusion is further supported by the increasing bivariate correlations across time.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the development of parental support and parental behavioral control throughout adolescence, using both parent and adolescent reports. Consistent with theoretical accounts of the development of parent–adolescent relationships and existing empirical studies (De Goede et al., 2009; Keijsers & Poulin, 2013; McGue et al., 2005; Shanahan et al., 2007; Smetana, 2011; Smetana et al., 2005), we found evidence of change in parenting as well as evidence of increasing similarity between parents' and adolescents' views during the course of adolescence. The trajectory of parental support was in accordance with our hypothesis. Parental support decreased from early to middle adolescence, and remained stable thereafter. For the trajectory of behavioral control, we predicted decrease but could not make specific assumptions regarding the shape of decrease. In line with our hypothesis, behavioral control decreased from early to middle adolescence, and we further found that the decrease was stronger between middle and late adolescence than between early and middle adolescence. These patterns were robust across gender and across reporters, with only a few exceptions. Regarding our research question that concerned the development of parent–adolescent divergence, our results supported the developmental psychological hypothesis. We found that adolescents and parents reported initially divergent parental support and behavioral control levels, which were increasingly convergent throughout adolescence.

Changes in Parenting During Adolescence: Parental Support and Behavioral Control

The finding that parental support develops in a curvilinear way corroborates theoretical hypotheses that, in the search for autonomy, parent–adolescent relationships undergo change, which includes also increased distance and less emotional parental support from parents (Branje et al., 2012). However, the increasing distance is rather a temporary move toward a more balanced and horizontal relationship. Our results support this view: the initial drop and then stability of parental support means that the relationship reaches a new balance in which parents are not expected to provide the same level of parental support (e.g., emotional warmth) they did at the outset of adolescence, because the relationship has been transformed into a more horizontal one. Contrary to previous studies (Shanahan et al., 2007), we found no evidence that parental support increases again after middle adolescence.

Behavioral control also decreased, but its trajectory was different from that of parental support. From early to middle adolescence, we found a significant drop in control according to all four reports. However, it continued to decrease at a higher rate from age 16 to age 18. These results are in accordance with previous studies of control trajectories in the Netherlands and the United States that showed linear decrease between ages 13 and 16 (Keijsers et al., 2009), as well as stronger decrease from age 16 on (Keijsers & Poulin, 2013). This, again, verifies the theoretical hypothesis about relationship transformation to a more horizontal relationship. As adolescents grow older and become more autonomous, they start relying less on their parents for behavioral limit setting. At the same time, parents allow more age‐appropriate autonomy to the adolescent and show more trust in her/his decision making and self‐regulatory skills (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Therefore, strict control becomes less appropriate.

Taken together, these two developments, along with the finding that the trajectories were the same across informants (with the only exception that parents of girls did not report change in parental support during this period), paint a rather clear picture of the relationships that transform toward more reciprocity (Steinberg & Silk, 2002; Youniss & Smollar, 1985). On the one hand, distance develops up to a degree; warmth decreases, and then levels‐off, stabilizing. On the other hand, behavioral control decreases throughout adolescence. In other words, from middle adolescence onward adolescents continue to develop more autonomously (less need for control), but do not further decrease in the warmth they feel as they stay connected to their parents. The fact that these patterns emerged from all four reports suggests that this transformation is normative.

In both parental support and control, age 16 may, on average, be a significant “turning point.” Parental support stops decreasing from this point on (with an exception for the perceptions of boys, see below), and control decreases more than it did in the previous phase. The idea of age 16 as a “turning point” is partly reflected in the legal system (e.g., youth of age 16 are allowed to drive a motorbike in many countries), as well as in the lay‐person or cultural perceptions (e.g., “sweet 16” celebration in the United States). It seems that when youth become 16, they stop being considered as “children.”

Development of Parent–Adolescent Divergence During Adolescence

Comparisons of parents' and adolescents' perceptions of parental support and behavioral control showed important findings for the development of parent–adolescent divergence on parenting. A common finding in both parental support and control was that those reporters in the parent–adolescent dyad who had the higher initial mean level showed the steeper decline across time. Put simply, those who started higher, dropped more. This resulted in converging views over time. For example, boys showed a higher mean level of parental support than mothers, but also showed a stronger decline than mothers, both during early to middle and during middle to late adolescence. In a different way, bivariate correlations also support this finding. Adolescent reports for both mothers and fathers became increasingly correlated with parental reports during adolescence, which shows that the rank‐order similarity of parents and adolescents increased between ages 13 and 18. Given higher shared variance between reporters, at age 18 parents and adolescents tended to agree more whether parental support and control were relatively higher or lower than in other families, and thus parents and adolescents became more in line with each other than was the case at age 13.

Past research is limited regarding how adolescent and parental views develop throughout adolescence. Similar research in the field of parent–adolescent discrepancies has been inconsistent regarding any age effects, with some studies showing no age effects and others showing few or temporary changes in discrepancies (Deković et al., 1997). Moreover, few studies in this field have been longitudinal. A study that used the same methodology as this study only found temporary changes in parent–adolescent divergent views of conflict (Van Lissa et al., 2015). Therefore, this study adds to this body of research, using a longer time frame spanning adolescence, as well as a combination of methods to detect divergence (latent means comparisons and change in correlations with age). Parents' and adolescents' perceptions of their relationships grew closer (i.e., became more alike) to each other during the course of adolescence. This can be the result of real‐life experience throughout adolescence, concerning the attainment of developmental tasks (Deković et al., 1997). Although early adolescents expect to achieve autonomy at an earlier age than parents do, during the adolescent years both adolescents and parents gradually reevaluate their earlier expectations. The convergence in views that we report might be an indication of this process.

At the outset of the study, adolescents viewed parents generally more leniently than parents viewed themselves. Adolescents reported more parental support, and less behavioral control than what parents reported. This is contrary to extant research, showing that parents feel themselves more supportive than school‐aged children do (Gaylord, Kitzmann, & Coleman, 2003). Although it might seem counter intuitive at first, this finding may mean that, at the outset of adolescence, parents may feel their support is not accepted by a “rebelling” adolescent; adolescents may feel sufficient parental support during that period. Therefore, parents might report less, and adolescents more parental support. On the other hand, this finding can be a sign of the de‐idealization of the parents in the eyes of the adolescents (Steinberg & Steinberg, 1994) and the changing nature of the parent–child relationship during adolescence. The parent–child relationship is hierarchical during childhood, and children hold a view of their parents as unique. This may be reflected in the higher support–lower behavioral control pattern in early adolescence in this study. In addition, when behavioral control is exerted effectively, it may be perceived by adolescents as guidance, not as unwanted control. But this view of parents tends to change during adolescence: during the individuation process (and with increasing cognitive capabilities), adolescents reevaluate and de‐idealize their parents (Levpušček, 2006). Additionally, early adolescents view parental behavioral control as legitimate, but this changes toward late adolescence (Smetana et al., 2005). Our results corroborate these theoretical accounts, as boys and girls have a more “advantageous” perception of the relationships with their parents at age 13 (higher parental support and lower control than parents report), but develop a more egalitarian (depicted by the drop in parental support and control) and pragmatic (depicted by the convergence with parental views) view of their parents later on.

Gender Differences in the Changes of Parenting During Adolescence

The aforementioned developmental patterns held largely across parent and adolescent gender, with a few exceptions.

Regarding parent gender, mothers and fathers differed only on the mean levels of both support and behavioral control. According to both parents and adolescents, mothers showed a significantly higher mean level of support, and behavioral control than fathers. This is in accordance with findings that mothers spend more time with, talk more to, and are more emotion‐directed to their adolescent children than fathers (De Goede et al., 2009; Maccoby, 2003). However, there were no differences between mothers and fathers in developmental changes in the support and behavioral control they offer to their adolescent children. The decline in support and behavioral control that both mothers and fathers show suggests that mothers and fathers adapt their parenting behaviors similarly during adolescence.

Parents did not differentiate between boys and girls, which is in accordance with recent meta‐analytic findings (Endendijk, Groeneveld, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, & Mesman, 2016). Although this might seem to contrast with the gender intensification hypothesis, parents may still differentiate between boys and girls, not in a general measure of support, like in this study, but in more specific ways of what mothers and fathers give support for, in boys and girls (e.g., Leaper & Friedman, 2007). This remains to be longitudinally examined in future studies.

Adolescent boys and girls only reported a difference in behavioral control. Girls perceived a significantly slower decline in behavioral control than boys. This finding was further corroborated by the parent–adolescent comparisons, according to which parents and boys did not differ in the rate of change in behavioral control during the first half of adolescence, whereas parents and girls did (see Table 4). We are not aware of similar extant findings, but we speculate that since girls mature faster than boys, they may expect a stronger decline in behavioral control, which may lead them to perceive the actual decline as less than what is expected. This hypothesis should be explored further in future research.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this study is that it investigates the development of two parenting measures, parental support and behavioral control, instead of one, as is usually done in other studies (e.g., Keijsers et al., 2009; Shanahan et al., 2007). Second, following the suggestions from Laursen and Collins (2009), the use of reports from mothers, fathers, and adolescents significantly adds to the developmental parenting research that has been generally dominated by views of one or two family members. Finally, the use of a longitudinal design is an asset of this study. Following participants for a span of 6 years helps improve our understanding on how parent–adolescent relationship transforms across adolescence.

Besides its strengths, this study also has limitations. The first limitation is the sample used, which was rather homogeneous, consisting mainly of Dutch families with married parents, of medium to high SES. Parenting practices have been shown to differ across cultural groups, across countries, across parental marital status, as well as across socioeconomic strata within cultural and ethnic groups (e.g., Bornstein, Cote, Haynes, Hahn, & Park, 2010; Smetana, 2017). Even though we controlled for SES in the LGMs, it is possible that the pattern of results reported in this study does not generalize, or only partially generalizes, to other ethnic and socioeconomic contexts. Further studies employing heterogeneous samples are needed to replicate this pattern. Another limitation is that, even though this study investigated two dimensions of parenting, this operationalization is still narrow in light of the breadth of the parenting construct (Bornstein, 2015; Smetana, 2017). A third limitation is that only questionnaire data were used in this study. Although questionnaires are an important source of information for psychological and behavioral phenomena, observations could be of added value, as they can offer one more perspective on parenting. Finally, this study used a relatively less often used measure of parental support. This may hinder comparability with extant studies. Future studies may be useful to aim at a unification of the different measures of parental support.

Conclusion

This study showed how parenting, conceptualized as both parental support and behavioral control, develops throughout adolescence, covering the whole period of adolescence (ages 13 to 18). Using longitudinal family data, this study allowed the investigation of the development of parenting according to mothers and fathers, as well as the adolescents' perceptions of mothers and fathers. Adolescence is indeed a period during which parent–adolescent relationships change significantly, as they gradually transform from vertical/hierarchical to more horizontal. Finally, although parents and adolescents hold significantly divergent views regarding parenting the in early adolescence, the progression toward middle and then late adolescence brings these initially divergent views closer together.

These results can have significant implications for prevention and interventions on the family system. For example, practitioners can have in mind that it is normative for adolescents and parents to hold different views of their relationship during early adolescence and that these differences are expected to ease toward middle/late adolescence. Furthermore, the drop in parental support is probably not a sign of worsening family relationships, but rather a sign of normative development. Finally, our results show that few, if any, differences exist between adolescent boys and girls in how they perceive their relationships with their parents.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Model fit indices of the measurement invariance analyses.

The copyright line for this article was changed on June 29, 2018 after original online publication.

Data from the Research on Adolescent Development and Relationships (RADAR) study were used. RADAR has been financially supported by main grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (GB‐MAGW 480‐03‐005) and Stichting Achmea Slachtoffer en Samenleving (SASS) to RADAR PI's, and from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research to the Consortium on Individual Development (CID; 024.001.003).

Notes

Results of these analyses can be obtained from the first author upon request.

The initial results without controlling for SES can be obtained from the first author upon request.

References

- Baumrind, D. (1968). Authoritarian vs. authoritative parental control. Adolescence, 3(11), 255–272. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1295900042/citation/10EFC57FBFF34C25PQ/1 [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status In Larzelere R. E., Morris A. S., & Harrist A. W. (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11–34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 10.1037/13948-002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. , Jaffee, S. R. , Sligo, J. , Woodward, L. , & Silva, P. A. (2005). Intergenerational transmission of warm‐sensitive‐stimulating parenting: A prospective study of mothers and fathers of 3‐year‐olds. Child Development, 76, 384–396. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. , Steinberg, L. , & Draper, P. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647–670. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S. , Hartnett, C. S. , Fingerman, K. L. , Zarit, S. H. , & Antonucci, T. C. (2015). Extending the intergenerational stake hypothesis: Evidence of an intra‐individual stake and implications for well‐being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 877–888. 10.1111/jomf.12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blos, P. (1967). The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 22, 162–186. 10.1080/00797308.1967.11822595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M. H. (2015). Children's parents In Bornstein M. H. & Leventhal T. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, Vol.4: Ecological settings and processes in developmental systems (7th ed., pp. 55–132). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M. H. , Cote, L. R. , Haynes, O. M. , Hahn, C. , & Park, Y. (2010). Parenting knowledge: Experiential and sociodemographic factors in European American mothers of young children. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1677–1693. 10.1037/a0020677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branje, S. J. T. , Laursen, B. , & Collins, W. A. (2012). Parent–child communication during adolescence In Vangelisti A. L. (Ed.), Routledge handbook of family communication (Vol. 2, pp. 271–286). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Branje, S. J. , van Aken, M. A. , & van Lieshout, C. F. (2002). Relational support in families with adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 351–362. 10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Liu, M. , & Li, D. (2000). Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 401–419. 10.1037/0893-3200.14.3.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, W. A. , & Russell, G. (1991). Mother–child and father–child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review, 11(2), 99–136. 10.1016/0273-2297(91)90004-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter, A. C. , Helms‐Erikson, H. , Updegraff, K. , & McHale, S. M. (1999). Conditions underlying parents' knowledge about children's daily lives in middle childhood: Between‐and within‐family comparisons. Child Development, 70, 246–259. 10.1111/1467-8624.00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. D. , Crouter, A. C. , & McHale, S. M. (2006). Implications of shift work for parent–adolescent relationships in dual‐earner families. Family Relations, 55, 450–460. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00414.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Goede, I. H. , Branje, S. J. T. , & Meeus, W. H. (2009). Developmental changes in adolescents' perceptions of relationships with their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 75–88. 10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deković, M. , Noom, M. J. , & Meeus, W. (1997). Expectations regarding development during adolescence: Parental and adolescent perceptions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26, 253–272. 10.1007/s10964-005-0001-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dufur, M. J. , Howell, N. C. , Downey, D. B. , Ainsworth, J. W. , & Lapray, A. J. (2010). Sex differences in parenting behaviors in single‐mother and single‐father households. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1092–1106. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00752.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endendijk, J. J. , Groeneveld, M. G. , Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J. , & Mesman, J. (2016). Gender‐differentiated parenting revisited: Meta‐analysis reveals very few differences in parental control of boys and girls. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0159193 10.1371/journal.pone.0159193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M. E. , McHale, S. M. , Crouter, A. C. , & Cumsille, P. (2003). Sibling differentiation: Sibling and parent relationship trajectories in adolescence. Child Development, 74, 1261–1274. 10.1111/1467-8624.00606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63, 103–115. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord, N. K. , Kitzmann, K. M. , & Coleman, J. K. (2003). Parents' and children's perceptions of parental behavior: Associations with children's psychosocial adjustment in the classroom. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(1), 23–47. 10.1207/S15327922PAR0301_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hafen, C. A. , & Laursen, B. (2009). More problems and less support: Early adolescent adjustment forecasts changes in perceived support from parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 193–202. 10.1037/a0015077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsen, M. , Vollebergh, W. , & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 319–335. https://doi.org/1005147708827 [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J. P. , & Lynch, M. E. (1983). The intensification of gender‐related role expectations during early adolescence In Brooks‐Gunn J. & Petersen A. C. (Eds.), Girls at puberty (pp. 201–228). New York, NY; Plenum Press; 10.1007/978-1-4899-0354-9_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. M. (1975). Fathers, mothers and sex typing. Sociological Inquiry, 45(1), 15–26. 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1975.tb01210.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers, L. , Branje, S. J. T. , VanderValk, I. E. , & Meeus, W. (2010). Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 88–113. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00631.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers, L. , Frijns, T. , Branje, S. J. T. , & Meeus, W. (2009). Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation, and control with delinquency: Moderation by parental support. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1314–1327. 10.1037/a0016693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers, L. , & Poulin, F. (2013). Developmental changes in parent–child communication throughout adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 49, 2301–2308. 10.1037/a0032217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M. , & Stattin, H. (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36, 366 10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M. , Stattin, H. , & Burk, W. J. (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 39–64. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam, C. B. , McHale, S. M. , & Crouter, A. C. (2012). Parent–child shared time from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 83, 2089–2103. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01826.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, B. , & Collins, W. A. (2009). Parent–child relationships during adolescence In Lerner R. M. & Steinberg L. (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development (pp. 3–42). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leaper, C. , & Friedman, C. K. (2007). The socialization of gender In Grusec J. E. & Hastings P. D. (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 561–587). New York, NY: Guilford; Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, J. T. Y. , Shek, D. T. L. , Li, L. (2016). Mother–child discrepancy in perceived family functioning and adolescent developmental outcomes in families experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 2036–2048. 10.1007/s10964-016-0469-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levpušček, M. P. (2006). Adolescent individuation in relation to parents and friends: Age and gender differences. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3, 238–264. 10.1080/17405620500463864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby, E. E. (2003). The gender of child and parent as factors in family dynamics In Crouter A. C. & Booth A. (Eds.), Children's influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships (pp. 191–206). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McGue, M. , Elkins, I. , Walden, B. , & Iacono, W. G. (2005). Perceptions of the parent–adolescent relationship: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 41, 971–984. 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, W. (2016). Adolescent psychosocial development: A review of longitudinal models and research. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1969–1993. 10.1037/dev0000243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998. –2012). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, A. , & Saebel, J. (1997). Mother–son, mother–daughter, father–son, and father–daughter: Are they distinct relationships? Developmental Review, 17, 111–147. 10.1006/drev.1996.0431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, L. , McHale, S. M. , Crouter, A. C. , & Osgood, D. W. (2007). Warmth with mothers and fathers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Within‐ and between‐families comparisons. Developmental Psychology, 43, 551–563. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. L. (2007). A longitudinal study of perceived differences in parental control and parent–child relational qualities in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 156–188. 10.1177/0743558406297509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. L. (2008). Perceived parental control and parent–child relational qualities in early adolescents in Hong Kong: Parent gender, child gender and grade differences. Sex Roles, 58, 666–681. 10.1007/s11199-007-9371-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal, M. (1987). Are sons and daughters treated more differently by fathers than by mothers? Developmental Review, 7(3), 183–209. 10.1016/0273-2297(87)90012-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development: How teens construct their worlds. Chichester, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 19–25. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, J. , Crean, H. F. , & Campione‐Barr, N. (2005). Adolescents' and parents' changing conceptions of parental authority. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2005, 31–46. 10.1002/cd.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L. , & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents In Bornstein M. H. (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (pp. 103–133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L. , & Steinberg, W. (1994). Crossing paths: How your child's adolescence triggers your own crisis. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta, C. J. , Criss, M. M. , Shaw, D. S. , Lacourse, E. , Hyde, L. W. , & Dishion, T. J. (2011). Antecedents and outcomes of joint trajectories of Mother–Son conflict and warmth during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 82, 1676–1690. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01626.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lissa, C. J. , Hawk, S. T. , Branje, S. J. T. , Koot, H. M. , Van Lier Pol, A. C. , & Meeus, W. H. J. (2015). Divergence between adolescent and parental perceptions of conflict in relationship to adolescent empathy development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 48–61. 10.1007/s10964-014-0152-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. , Pomerantz, E. M. , & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents' control in early adolescents' psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78, 1592–1610. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , & Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. Chichester, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell; 10.1002/9781118356258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yap, M. B. H. , Pilkington, P. D. , Ryan, S. M. , & Jorm, A. F. (2014). Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 156, 8–23. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youniss, J. , & Smollar, J. (1985). Adolescents' relations with their mothers, fathers and peers. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Model fit indices of the measurement invariance analyses.