Abstract

Objectives

To determine if disease duration and number of prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) affect response to therapy in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Associations between disease duration or number of prior DMARDs and response to therapy were assessed using data from two randomised controlled trials in patients with established RA (mean duration, 11 years) receiving adalimumab+methotrexate. Response to therapy was assessed at week 24 using disease activity outcomes, including 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28(CRP)), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), and proportions of patients with 20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) responses.

Results

In the larger study (N=207), a greater number of prior DMARDs (>2 vs 0–1) was associated with smaller improvements in DAS28(CRP) (–1.8 vs –2.2), SDAI (–22.1 vs –26.9) and HAQ-DI (–0.43 vs –0.64) from baseline to week 24. RA duration of >10 years versus <1 year was associated with higher HAQ-DI scores (1.1 vs 0.7) at week 24, but results on DAS28(CRP) and SDAI were mixed. A greater number of prior DMARDs and longer RA duration were associated with lower ACR response rates at week 24. Data from the second trial (N=67) generally confirmed these findings.

Conclusions

Number of prior DMARDs and disease duration affect responses to therapy in patients with established RA. Furthermore, number of prior DMARDs, regardless of disease duration, has a limiting effect on the potential response to adalimumab therapy.

Keywords: dmards (synthetic), rheumatoid arthritis, tnf-alpha, DAS28

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Longer disease duration and delayed start of disease-modifying therapies (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, DMARDs) are associated with poorer disease control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Prior DMARD use has also been shown to affect treatment outcomes in RA.

What does this study add?

Our results demonstrated that the number of prior DMARDs and disease duration affect responses to adalimumab therapy in patients with established RA.

Number of prior DMARDs appears to limit treatment response regardless of disease duration.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

The use of multiple DMARDs prior to initiating therapy with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (in this case, adalimumab) constitutes a poor prognostic factor and may also mediate the poor prognosis of longer disease duration.

This should be taken into consideration for future clinical trial design when defining inclusion criteria, which currently limit patient access mostly by duration of disease but not by number of prior DMARDs.

Introduction

A delay in initiating disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can negatively affect long-term outcomes and be associated with greater disease activity, more extensive joint damage and worsened physical disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).1 2 Conversely, rapid implementation of conventional synthetic (cs) DMARDs or tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) results in better disease control than delaying start of therapy.3–7

However, longer disease duration is not necessarily associated with reduced clinical responsiveness based on observations that patients with different disease durations achieve similar outcomes in clinical trials.8–10 In contrast, patients with RA who have failed methotrexate or TNFi therapy have much lower response rates than methotrexate-naïve patients,11 although it is not clear if these differences are primarily related to having failed an increasing number of prior DMARD therapies or increasing disease duration.

A pooled analysis of 14 RA trials demonstrated that prior use of csDMARDs was associated with reduced likelihood of treatment response to a subsequent csDMARD independently of disease duration.12 Similarly, the likelihood of achieving 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) response (reduction >1.2 points) increased as the number of prior biological therapies decreased (p=0.003).13 In line with this, a lower percentage of patients with ≥3 failed TNFi therapies achieved DAS28 remission compared with patients who failed 1–2 TNFi therapies in an abatacept study.14 However, it remains unknown if response to the first biologic DMARD, in particular a TNFi, depends on disease duration or prior numbers of failed csDMARDs.

To address this question, we assessed whether use of fewer prior csDMARDs, rather than disease duration, might be predictive of achievement of treatment response using data from a large, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial of adalimumab in patients with established RA who had active disease despite methotrexate. To confirm the findings, we analysed data from an additional smaller adalimumab trial.

Patients and methods

Study designs

This post hoc analysis included data from two trials, DE019 (NCT00195702) and ARMADA (conducted prior to trial registration requirement), of which the latter was used to confirm the results. The methods and primary results have been previously published for both trials.10 15 Briefly, both studies were randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials that evaluated the safety and efficacy of adalimumab versus placebo as an add-on therapy to background methotrexate in patients with established RA with active disease. Patients in DE019 were randomised (1:1:1) to receive 52 weeks of treatment with adalimumab 40 mg every other week (eow), adalimumab 20 mg every week (ew) or placebo ew+concomitant methotrexate ew.10 Patients in ARMADA were randomised to receive 24 weeks of adalimumab 20, 40 or 80 mg eow or placebo+concomitant methotrexate ew.15 Both studies were performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocols were approved by ethics review boards of each study center. Written informed consent was obtained before the initiation of study procedures.

This analysis included only patients who received treatment with adalimumab 40 mg eow+methotrexate ew in the two trials. Data from other dosing regimen groups were excluded from this analysis because they are not in clinical use for RA. Patients had received prior csDMARDs (see online supplementary table S1); prior biological therapy was an exclusion criterion in both studies.

annrheumdis-2018-214918supp001.pdf (483.3KB, pdf)

Outcomes

Treatment outcomes considered in this analysis included the following: American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response, defined as ≥20% (ACR20), ≥50% (ACR50) and ≥70% (ACR70) improvement from baseline at week 24; mean DAS28 based on C-reactive protein (DAS28(CRP)); Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI); and Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) at week 24. The mean changes from baseline to week 24 in DAS28(CRP), SDAI and HAQ-DI were also calculated; a reduction in each of these indices indicated improvement in disease activity.

The percentages of patients with HAQ-DI <0.5, DAS28(CRP) low disease activity (LDA, DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2) and SDAI LDA (SDAI ≤11) at week 24 were assessed in subgroups cross-tabulated for disease duration and number of prior DMARDs.

Statistical analysis

Patients were grouped according to the duration of RA, that is, time since diagnosis: ≤1 year, >1 to 5 years, >5 to10 years and >10 years for patients in DE019 and ≤5 years and >5 to 10 years since the diagnosis of RA for patients in ARMADA. Patients were also grouped according to the number of prior DMARDs received: methotrexate+0 or 1 prior DMARD, methotrexate+2 prior DMARDs and methotrexate+>2 prior DMARDs for patients in both trials. A separate sensitivity analysis was also conducted in the DE019 study for patient groups based on RA duration tertiles, where patients were divided into three equal-sized groups based on RA duration from shortest to longest.

The effect of RA duration and number of prior DMARDs was determined at week 24 for each treatment outcome in each subgroup. Associations between disease duration or extent of prior DMARD use variables and efficacy endpoints were modelled while controlling for the other variables using multivariate regression analysis. Logistic regression was used for dichotomous dependent variables, and linear regression was used for continuous dependent variables. Subgroups based on disease duration and number of prior DMARDs were assigned ordinal scores and treated as ordinal covariates. The estimate from the logistic model denotes the increase in the odds of ACR response per 1-DMARD category increase/1-duration category increase, while the estimate from the linear model denotes the increase in mean outcome value per 1-DMARD category increase/1-duration category increase. For regression models with mean changes from baseline in DAS28(CRP), SDAI or HAQ as the dependent variables, a positive regression coefficient indicates a smaller improvement.

Results

Patient population

This analysis included 207 patients from DE019 and 67 patients from ARMADA who were treated with adalimumab 40 mg eow+methotrexate. In the DE019, RA duration was ≤1 year for 9 patients (4.3%), >1 to 5 years for 62 patients (30.0%), >5 to 10 years for 43 patients (20.8%) and >10 years for 93 patients (44.9%). The mean numbers of prior DMARDs (including methotrexate) in these RA duration groups were 1.4, 2.0, 2.1 and 2.7, respectively (table 1). Of the 207 patients, 75 (36.2%), 62 (30.0%) and 70 patients (33.8%) had received methotrexate+0 or 1, 2 and >2 prior DMARDs, respectively (table 1). All patients in the DE019 study had received prior csDMARDs; most common prior csDMARDs were methotrexate (all but one patient), hydroxychloroquine (45%) and sulfasalazine (26%; see online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of patients receiving adalimumab+methotrexate in the DE019 study

| Mean (SD)* | DE019 (N=207) | ||||||

| Disease duration | Prior DMARD treatment | ||||||

| ≤1 year n=9 |

>1–5 years n=62 |

>5–10 years n=43 |

>10 years n=93 |

MTX+0–1 n=75 |

MTX+2 n=62 |

MTX+>2 n=70 |

|

| Age, years | 55.2 (18.0) | 51.3 (15.7) | 56.6 (12.3) | 59.1 (11.1) | 58.7 (2.8) | 54.4 (14.7) | 54.7 (12.9) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 5 (55.6) | 48 (77.4) | 33 (76.7) | 72 (77.4) | 58 (77.3) | 50 (80.7) | 50 (71.4) |

| RA duration, years | 0.7 (0.2) | 3.1 (1.3) | 7.1 (1.3) | 19.1 (8.0) | 9.3 (10.4) | 11.3 (9.3) | 12.6 (7.5) |

| Prior DMARD treatments† | 1.4 (0.5) | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.6) | 1.0 (0) | 2.0 (0) | 4.0 (1.1) |

| DAS28(CRP) | 6.4 (1.1) n=8 | 5.6 (0.8) n=46 | 5.7 (0.9) n=29 | 5.8 (0.7) n=69 | 5.7 (0.9) n=54 | 5.8 (0.8) n=47 | 5.7 (0.8) n=51 |

| SDAI | 49.0 (17.2) n=8 | 38.5 (11. 8) n=46 | 40.1 (13.1) n=29 | 41.6 (11.1) n=69 | 40.0 (12.1) n=54 | 41.9 (12.0) n=47 | 40.6 (12.5) n=51 |

| HAQ-DI | 1.6 (0.9) n=8 | 1.3 (0.7) n=46 | 1.3 (0.6) n=29 | 1.5 (0.6) n=69 | 1.4 (0.7) n=54 | 1.4 (0.6) n=47 | 1.4 (0.7) n=51 |

*Values are means (SD) unless specified otherwise.

†Including methotrexate.

DAS28(CRP), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; RA, Rheumatoid arthritis; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

In the cross-tabulation analysis, the highest percentage of patients had received >2 prior DMARDs and had >10 years of disease duration (19.8%) followed by those with two prior DMARDs and >10 years of disease duration or 0–1 DMARDs and >1 to 5 years of disease duration (both 14.0%; see online supplementary figure S1).

In ARMADA, the duration of RA was ≤5 years for 51 patients (76.1%) and >5 to 10 years for 16 patients (23.9%). A total of 41 (61.2%), 13 (19.4%) and 13 patients (19.4%) had received methotrexate+0–1, 2 and >2 prior DMARDs, respectively (table 2). Overall, 76% of patients in the ARMADA study had received prior csDMARDs; most common prior csDMARDs were gold and gold preparations (52%), sulfasalazine (33%) and methotrexate (24%; see online supplementary table S1). In the cross-tabulation analysis, the highest percentage of patients (50.7%) were in the methotrexate +0–1 prior DMARDs and ≤5 years of disease duration category (see online supplementary figure S1). Not surprisingly, as duration of disease increased, the number of prior DMARD treatments also tended to increase in both trials (tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of patients receiving adalimumab+methotrexate in the ARMADA study

| Mean (SD)* | ARMADA (N=67) | ||||

| Disease duration | Prior DMARD treatment | ||||

| ≤5 years n=51 |

>5–10 years n=16 |

MTX+0–1 n=41 |

MTX+2 n=13 |

MTX+>2 n=13 |

|

| Age, years | 55.2 (10.4) | 61.3 (13.6) | 55.5 (10.0) | 61.4 (14.6) | 55.6 (12.0) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 38 (74.5) | 12 (75.0) | 32 (78.0) | 10 (76.9) | 8 (61.5) |

| RA duration, years | 3.6 (1.2) | 6.0 (0.0) | 3.9 (1.4) | 4.2 (1.7) | 4.9 (1.2) |

| Prior DMARD treatments† | 1.3 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.5) | 0.6 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.0) | 3.6 (1.0) |

| DAS28(CRP) | 5.7 (0.8) | 5.5 (0.9) | 5.8 (0.7) | 5.4 (0.9) | 5.5 (0.8) |

| SDAI | 40.1 (10.6) | 37.4 (11.2) | 41.5 (10.8) | 36.8 (10.4) | 35.7 (10.1) |

| HAQ-DI | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.4) |

*Values are means (SD) unless specified otherwise.

†Including methotrexate.

DAS28(CRP), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

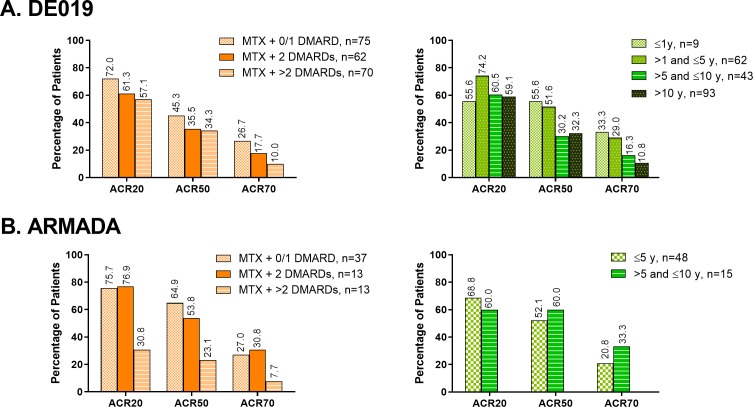

Treatment outcomes

In the DE019 study, the proportion of patients with ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses decreased linearly as the number of prior DMARDs increased (figure 1A). Although there was a general trend towards declining responsiveness with increases in disease duration, declines in ACR50 and ACR70 responses were primarily seen when comparing patients with a disease duration of >5 years versus ≤5 years.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients with ACR20/50/70 response in subgroups based on prior exposure to DMARDs or prior disease duration in (A) DE019 and (B) ARMADA at week 24. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate.

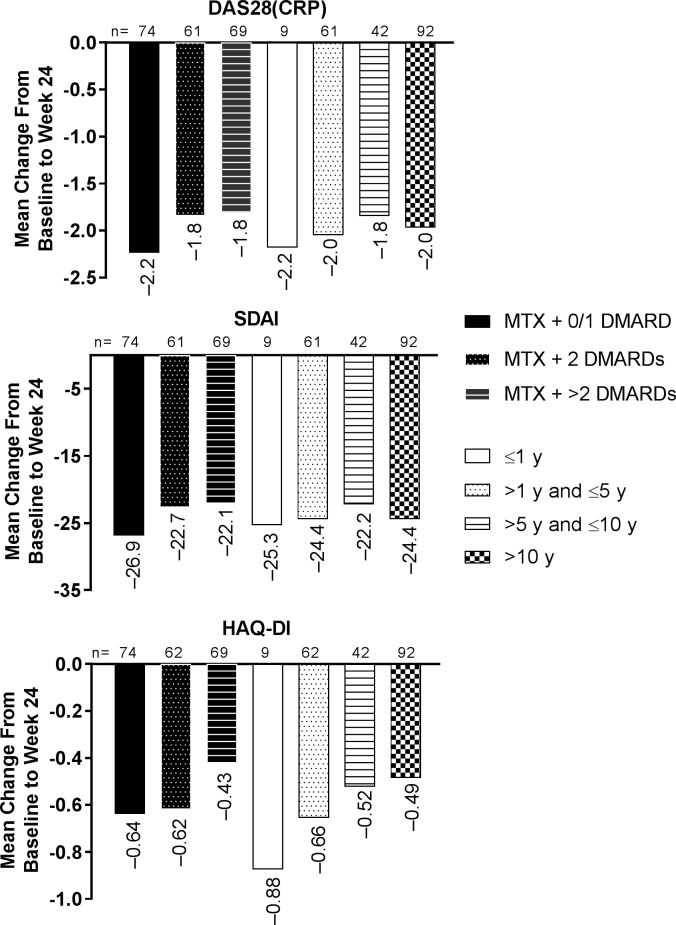

The improvement from baseline in disease activity was highest among patients who had received methotrexate+0–1 prior DMARDs and numerically lowest among those who had previously received methotrexate+2 or more prior DMARDs (figure 2). In this context, it is noteworthy that baseline disease activity in the DE019 trial did not differ much between groups. Importantly, disease duration did not have an impact on improvement from baseline to week 24 in disease activity by DAS28(CRP) or SDAI. When assessed for physical function, the improvement in HAQ-DI from baseline to week 24 decreased with increasing number of DMARDs and disease duration (figure 2). Furthermore, mean disease activity (DAS28(CRP) and SDAI) and mean absolute HAQ-DI at week 24 showed a numerical increase with increasing numbers of prior DMARDs. Results were more varied with longer disease duration (see online supplementary figure S2A).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline to week 24 in mean DAS28(CRP), SDAI and HAQ-DI in subgroups based on prior exposure to DMARDs or prior disease duration in DE019. DAS28(CRP), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

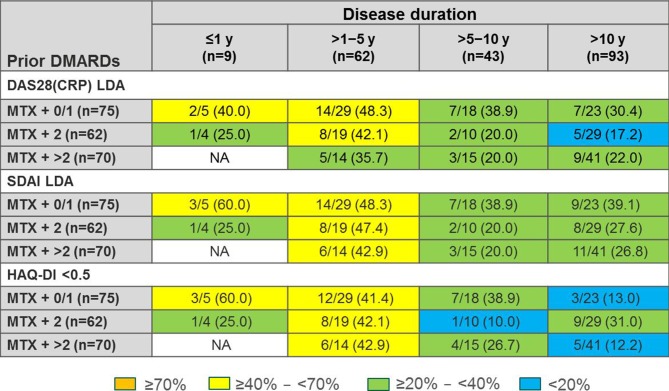

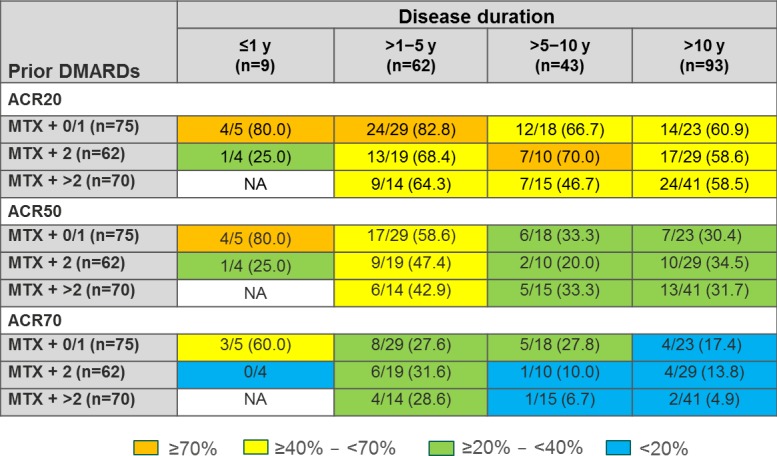

In the DE019 study cross-tabulation analysis, higher percentages of patients with fewer prior DMARDs and shorter disease duration achieved ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses compared with patients with higher numbers of prior DMARDs and/or longer disease duration (figure 3). This was also observed for achievement of DAS28(CRP) LDA, SDAI LDA and HAQ-DI <0.5 (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Patients achieving ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses in each disease duration and prior DMARD category at week 24 in the DE019 study. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable.

Figure 4.

Patients achieving DAS28(CRP) LDA, SDAI LDA and HAQ-DI <0.5 responses in each disease duration and prior DMARD category at week 24 in the DE019. DAS28(CRP), 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; LDA, low disease activity; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

These results were generally confirmed by the ARMADA trial; lower ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 response rates at week 24 were observed among patients with >2 prior DMARDs+methotrexate versus patients with ≤2 prior DMARDs+methotrexate (figure 1B). Similar to observations in DE019, mean DAS28(CRP), SDAI and HAQ-DI at week 24 were higher in patients with higher number of prior DMARDs (see online supplementary figure S2B). Disease duration had no apparent impact on achievement of ACR responses in ARMADA (figure 1B) or mean disease activity or HAQ-DI at week 24 (see online supplementary figure S2B).

In the ARMADA cross-tabulation analysis, higher percentages of patients with fewer prior DMARDs, regardless of disease duration, generally achieved ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses compared with patients with higher number of prior DMARDs (see online supplementary figure S3). Similar results were observed with achievement of DAS28(CRP) LDA, SDAI LDA and HAQ-DI <0.5 (see online supplementary figure S4).

Regression analysis

The multivariate regression analysis of DE019 showed that a greater number of prior DMARDs or longer disease duration was associated with decreased odds of achieving ACR outcome criteria at week 24 with significantly decreased odds for achieving ACR70 (both with greater number of prior DMARDs or longer disease duration) and ACR50 (with longer disease duration only; online supplementary table S2). Longer disease duration was also associated with significantly smaller improvement from baseline to week 24 in HAQ-DI (p<0.05; online supplementary table S2). No significant association was observed in the other disease activity measures or change in disease activity from baseline analyses.

Disease duration tertile sensitivity analysis

In the RA duration tertile analysis, 69 patients were allocated to each of the groups. The mean±SD RA duration was 2.8±1.4 years in the first tertile, 8.6±2.5 in the second tertile and 21.7±7.7 in the third tertile (see online supplementary table S3). Patients in the third tertile were more likely to be older, to be women and to have used more DMARDs prior to study entry than patients in the first or second tertile. Disease activity and HAQ-DI were similar between the groups at baseline.

The proportions of patients with ACR responses were lower in the second and third tertiles versus the first tertile (see online supplementary figure S5). Similarly, patients in the first tertile had lower HAQ-DI at week 24 and greater improvement from baseline to week 24 in HAQ-DI versus the second and third tertiles. However, disease activity and changes in disease activity from baseline to week 24 were generally similar between the tertiles. Thus, the lack of association between disease duration and change in disease activity by SDAI or DAS28(CRP) was also seen when disease duration was categorised by tertiles rather than fixed cut-off points.

Discussion

The results of this retrospective analysis of DE019, a large, randomised, double-blind multicentre clinical trial, showed that after 24 weeks of treatment, progressively lower proportions of patients achieved improvement of disease activity as the number of prior DMARDs increased. This was observed for the categorical ACR response rates as well as in reduction of continuous composite disease activity measures DAS28(CRP) and SDAI. Although a similar trend was observed with increasing disease duration, the results were more variable, suggesting that number of prior DMARDs may have an independent effect on disease outcomes. These results were generally confirmed in the smaller ARMADA trial. The most marked differences were observed between patients who had received methotrexate +>2 prior DMARDs as compared with methotrexate with 0–1 prior DMARDs.

We have previously demonstrated that HAQ improvement decreases with increasing disease duration.16 17 In our current analysis, the change in HAQ-DI from baseline to week 24 decreased with greater number of prior DMARDs and increasing disease duration. Furthermore, longer disease duration was associated with a significantly smaller improvement from baseline in HAQ-DI, and attainment of HAQ-DI <0.5 was also less frequent in those who had the most courses of prior DMARDs or longer disease duration based on the cross-tabulation analysis. This is in line with previous studies that showed that physical function has an activity-related and a damage-related component and with increasing damage (which accrues with increasing disease duration), improvement of HAQ-DI becomes more difficult.16 17

Although we noticed the expected trend for increased number of DMARDs (from 1.4 to 2.7) with increasing disease duration (from <1 year to >10 years), disease duration did not differ much with increasing number of prior DMARDs (range from 9.3 years to 12.6 years). This contrasts with reported findings of longer disease duration associated with increased number of prior DMARDs in a previous study.18 The same study also demonstrated that longer disease duration and prior use of biologic DMARDs (TNFi), but not csDMARDs, was associated with significantly reduced likelihood of achieving sustained remission.18 Association between higher number of prior DMARDs and reduced likelihood of achieving treatment response has been demonstrated in a few other RA studies,14 19 20 including two certolizumab pegol studies.13 21 In our study, a greater number of prior DMARDs and longer disease duration were associated with significantly decreased odds of achieving improvement as measured by ACR response. This relationship for improvement in disease activity was also observed in the cross-tabulation analysis in the DE019 study but not in the ARMADA study, which demonstrated better disease outcomes with lower number of prior DMARDs irrespective of disease duration. Although a direct relationship between increasing disease duration and higher number of prior DMARDs to disease activity seems likely, there also might be different mechanisms contributing to the effect. Thus, the current findings add to previous observations that a decreasing responsiveness is due to having failed more therapies13 rather than having longer disease duration, although there is an obvious overlap between these two. For example, more cycles of failing DMARDs might select a phenotype that is resistant to a new treatment because different pathogenetic pathways may have become ‘imprinted’.22 23 To this end, our analysis demonstrated that in patients with established RA, the number of prior DMARDs had an impact on disease outcomes, specifically changes in disease activity.

Overall, our results suggest that long delays and/or the use of multiple DMARDs prior to initiating therapy with a TNFi (in this case, adalimumab) may actually reduce the potential magnitude of the response to the TNFi. However, it must be noted that the present analyses only evaluated studies in which patients had been treated with prior csDMARD for prolonged periods of time rather than using them for only short term if a low disease activity was not achieved.24 Therefore, these findings pertain to these specific situations, and the impact of the prior number of csDMARDs may be different in studies that switched csDMARDs rapidly before introduction of biologic DMARDs.25 Importantly, the European League Against Rheumatism has declared the failure of two csDMARDs as a poor prognostic marker,26 which is generally in line with the present findings as well as other observations.27 Thus, patients who do not respond to methotrexate therapy initiated early after a diagnosis of RA appear to benefit most from addition of adalimumab.28 These analyses demonstrate the benefits of early therapeutic intervention and underscore the need for more standardised treatment guidelines for early RA, particularly in socioeconomic regions lacking rheumatologists, where patients are often managed or monitored by general practitioners or allied health workers. Furthermore, these findings should be considered in future trials when defining inclusion criteria not only by duration of disease but also by number of prior DMARDs.

This analysis has certain limitations, including its post hoc nature and restriction to adalimumab data; however, differences between TNFis are not expected.29 The number of patients included in some prior treatment or disease duration stratum was small; thus, the analysis lacks sufficient statistical power to detect small but potentially statistically significant relationships between some prior treatment or treatment duration subgroups and treatment outcome. Although generally similar observations were made in the ARMADA trial, the confirmation of the results was limited by several factors, particularly the much smaller patient numbers, which did not provide sufficient power to confirm all analyses, and differences in maximum disease durations and standards of care.

In conclusion, the number of prior DMARDs and disease duration affect response to therapy in patients with established RA, although the effect of the number of prior DMARDs on improvement in disease activity appears to be relevant regardless of disease duration. These results support recommendations that combination therapy with a biologic agent and methotrexate be initiated without delay in patients who do not have a satisfactory response to treatment with methotrexate alone.

Footnotes

Handling editor: David S Pisetsky

Contributors: AbbVie sponsored the studies, contributed to their design, and participated in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the writing, reviewing and approval of the final version. Medical writing was provided by Blair Jarvis, MSc, ELS, and Maria Hovenden, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC (North Wales, PA, USA) and was funded by AbbVie. This manuscript was based on work previously presented at the 2015 Annual Congress of the American College of Rheumatology and published as a conference abstract.

Funding: This study was funded by AbbVie.

Competing interests: DA has received grants and consulting fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, and Roche and consulting fees from Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Sandoz, Sanofi/Genzyme, and UCB. S-HP has nothing to disclose. DN has served on an advisory board for AbbVie and has clinical trial agreements with AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, UCB, and Zynerba. SC and SF are employees of AbbVie and may own stock/options. JM and DF are former employees of AbbVie and may own stock/options. JS has received grants and consulting fees from AbbVie Inc, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Lilly, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Pfizer, and Roche and consulting fees from Amgen, Astro, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Chugai, Gilead, Glaxo, ILTOO Pharma, Novartis-Sandoz, Samsung, Sanofi, and UCB.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Both studies were performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocols were approved by ethics review boards of each study centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

References

- 1. Molina E, Del Rincon I, Restrepo JF, et al. Association of socioeconomic status with treatment delays, disease activity, joint damage, and disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:940–6. 10.1002/acr.22542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Heide A, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW, et al. The effectiveness of early treatment with “second-line” antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:699–707. 10.7326/0003-4819-124-8-199604150-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, et al. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med 2001;111:446–51. 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00872-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gremese E, Salaffi F, Bosello SL, et al. Very early rheumatoid arthritis as a predictor of remission: a multicentre real life prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:858–62. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nell VP, Machold KP, Eberl G, et al. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2004;43:906–14. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emery P, Kvien TK, Combe B, et al. Combination etanercept and methotrexate provides better disease control in very early (<=4 months) versus early rheumatoid arthritis (>4 months and <2 years): post hoc analyses from the COMET study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:989–92. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Detert J, Bastian H, Listing J, et al. Induction therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate for 24 weeks followed by methotrexate monotherapy up to week 48 versus methotrexate therapy alone for DMARD-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: HIT HARD, an investigator-initiated study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:844–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smolen J, Collier D, Szumski A, et al. Effect of disease duration on clinical outcomes in moderate rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with etanercept plus methotrexate in the Preserve study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT, et al. Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1400–11. 10.1002/art.20217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2016;388:2023–38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson JJ, Wells G, Verhoeven AC, et al. Factors predicting response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of disease duration. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soriano ER, Dellepiane A, Salvatierra G, et al. Certolizumab pegol in a heterogeneous population of patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Future Sci OA 2018;4 10.4155/fsoa-2017-0149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schiff M, Zhou X, Kelly S, et al. FRI0160 efficacy of abatacept in RA patients with an inadequate response to anti-TNF therapy regardless of reason for failure, or type or number of prior anti-TNF therapy used. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67(Suppl 2). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:35–45. 10.1002/art.10697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aletaha D, Ward MM. Duration of rheumatoid arthritis influences the degree of functional improvement in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:227–33. 10.1136/ard.2005.038513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aletaha D, Strand V, Smolen JS, et al. Treatment-related improvement in physical function varies with duration of rheumatoid arthritis: a pooled analysis of clinical trial results. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:238–43. 10.1136/ard.2007.071415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Furst DE, Pangan AL, Harrold LR, et al. Greater likelihood of remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated earlier in the disease course: results from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America registry. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:856–64. 10.1002/acr.20452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andersson ML, Bergman S, Söderlin MK. The effect of socioeconomic class and immigrant status on disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: data from BARFOT, a multi-centre study of early RA. Open Rheumatol J 2013;7:105–11. 10.2174/1874312901307010105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Narváez J, Magallares B, Díaz Torné C, et al. Predictive factors for induction of remission in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab in clinical practice. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;45:386–90. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torrente-Segarra V, Urruticoechea Arana A, Sánchez-Andrade Fernández A, et al. RENACER study: assessment of 12-month efficacy and safety of 168 certolizumab PEG (PEGol) rheumatoid arthritis-treated patients from a Spanish multicenter national database. Mod Rheumatol 2016;26:336–41. 10.3109/14397595.2015.1101200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Nies JAB, Tsonaka R, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. Evaluating relationships between symptom duration and persistence of rheumatoid arthritis: does a window of opportunity exist? Results on the Leiden early arthritis clinic and ESPOIR cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:806–12. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morgan C, Lunt M, Brightwell H, et al. Contribution of patient related differences to multidrug resistance in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:15–19. 10.1136/ard.62.1.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Forget personalised medicine and focus on abating disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:3–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90. 10.1002/art.21405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kiely P, Walsh D, Williams R, et al. Outcome in rheumatoid arthritis patients with continued conventional therapy for moderate disease activity—the early RA network (ERAN). Rheumatology 2011;50:926–31. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lau CS, Chia F, Harrison A, et al. APLAR rheumatoid arthritis treatment recommendations. Int J Rheum Dis 2015;18:685–713. 10.1111/1756-185X.12754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smolen JS, Burmester G-R, Combe B, et al. Head-to-head comparison of certolizumab pegol versus adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year efficacy and safety results from the randomised EXXELERATE study. Lancet 2016;388:2763–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31651-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2018-214918supp001.pdf (483.3KB, pdf)