Abstract

Background

One of the most important steps taken by Beyond Batten Disease Foundation in our quest to cure juvenile Batten (CLN3) disease is to understand the State of the Science. We believe that a strong understanding of where we are in our experimental understanding of the CLN3 gene, its regulation, gene product, protein structure, tissue distribution, biomarker use, and pathological responses to its deficiency, lays the groundwork for determining therapeutic action plans.

Objectives

To present an unbiased comprehensive reference tool of the experimental understanding of the CLN3 gene and gene product of the same name.

Methods

BBDF compiled all of the available CLN3 gene and protein data from biological databases, repositories of federally and privately funded projects, patent and trademark offices, science and technology journals, industrial drug and pipeline reports as well as clinical trial reports and with painstaking precision, validated the information together with experts in Batten disease, lysosomal storage disease, lysosome/endosome biology.

Results

The finished product is an indexed review of the CLN3 gene and protein which is not limited in page size or number of references, references all available primary experiments, and does not draw conclusions for the reader.

Conclusions

Revisiting the experimental history of a target gene and its product ensures that inaccuracies and contradictions come to light, long‐held beliefs and assumptions continue to be challenged, and information that was previously deemed inconsequential gets a second look. Compiling the information into one manuscript with all appropriate primary references provides quick clues to which studies have been completed under which conditions and what information has been reported. This compendium does not seek to replace original articles or subtopic reviews but provides an historical roadmap to completed works.

Keywords: Batten, CLN3, JNCL, juvenile Batten, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis

The CLN3 gene, its regulation, gene product, CLN3 protein structure, tissue distribution, biomarker use, and pathological responses to its deficiency.

1. INTRODUCTION

Basic knowledge of the expression, regulation, structure, and function transmembrane‐bound and other proteins, enables the discovery of compounds to modulate their behavior. Along with analyses of disease‐causing mutations, investigators pursue creative approaches to restore protein function(s) and their associated pathways. Therefore, it is critically important that academicians, pharmaceutical investigators, and clinician scientists, be provided with a complete, easy‐to‐access, and an up‐to‐date State of the Science. Historically, one relied on review articles designed to summarize current thinking. However, an information explosion fueled by advances in molecular biology, genetic engineering, and new animal models, coupled with competing hypotheses of authors and size limits of review articles has resulted in the production of irregular, nonsystematic review articles in disease research leading to unintentional bias and widening knowledge gaps. To combat this problem, investigators new to the field must spend hundreds of hours sifting, reading, and evaluating original publications; defeating the purpose for which review articles were created.

Beyond Batten Disease Foundation (BBDF) has taken a lead to help support new and existing researchers in their quest for experimentally proven, unbiased, information. This manuscript is part of a larger strategic plan to advance research in Batten disease by fueling the creation of key physical and informational resources. The foundation worked with Thomson Reuters to gather referenced CLN3 gene and CLN3 protein information and with painstaking attention to detail, validated the information together with experts in CLN3 disease, lysosomal storage disease, and lysosome/endosome biology. The resultant indexed review of CLN3 and CLN3 is not limited in size, focuses on information from original articles, is reviewed by in‐area experts and inclusion in validated databases, and does not draw conclusions. By collecting all of the available information into a single, searchable reference manual, this review saves valuable time and ensures all topic areas are covered; however, readers will still need to review original literature cited here.

The information found within this reference tool is cultivated by: (a) MetaBase™ (version 6.20), a systems biology database, a former product of GeneGo, IntegritySM, (b) a drug and pipeline information database, Cortellis™, and (c) a drug and clinical trial information database, Thomson Innovation™, including patent information from around the world and public databases (December 2014 version), such as NCBI, Ensembl, dbSNP, UniProt, MGI and others. The information cultivated from these databases was then traced back its original source and rigorously reviewed. If the experiment was conducted more than once, all references were added.

The manual includes a research history of the CLN3 gene, discussion of gene regulation, protein structure, tissue distribution, co‐regulated gene expression, biomarker use, and pathological responses to CLN3 protein deficiencies in yeast through humans. Supplementary materials include a list of CLN3 research tools and their associated first‐published reports.

The authors note that following data extraction from the information systems mentioned above, the information gathered here was verified and the associated primary literature was cited along with the experimental methods used. We believe bioinformatics databases such as those mentioned above offer scientists the opportunity to access and cross‐reference a wide variety of biologically relevant data providing new insights and further means to validate their discoveries. However, the authors would like to stress that the databases listed here were used only to provide a framework for the document. The rapid release of new data from various –omics and other programs annotated using computational analysis sometimes leads to misinformation, which we found to be the case for the CLN3 gene and protein. Therefore, the authors worked to provide their readership with direct access to primary, experimentally proven data. Finally, the authors diligently tried to avoid summarizing the information herein in support of one hypothesis over another or drawing any conclusions for the reader. This comprehensive agnostic presentation of experimental findings is meant to complement and not overlap investigator‐driven primary and review literature.

2. GENERAL INFORMATION

2.1. Description of the CLN3 gene

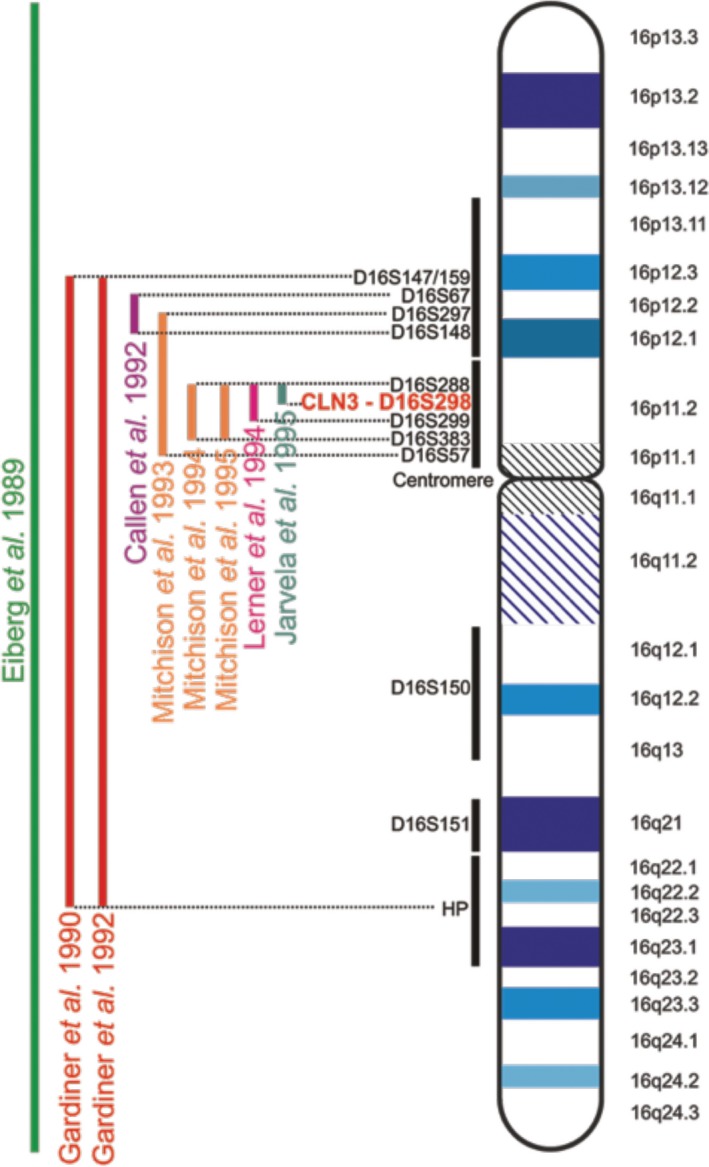

The official name of this gene is “ceroid‐lipofuscinosis, neuronal 3” and official symbol is CLN3. Less commonly used terms include BATTENIN, BTS, JNCL (Juvenile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis), and MGC102840. CLN3 was discovered using linkage analysis in search for the disease causing gene (mutation) in 48 children with progressive vision loss, seizures, decline of intellect and loss of motor ability (Eiberg, Gardiner, & Mohr, 1989). Researchers found a linkage between CLN3 disease and haptoglobin (140100) on chromosome 16q22 revealing the location of the CLN3 gene (Eiberg et al., 1989; Gardiner et al., 1990). Linkage studies in larger groups of families followed by physical mapping of markers by mouse/human hybrid cell analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization refined the coordinates of CLN3 to the interval between D16S288 and D16S298 (see Figure 1: LinkageMapping, (Callen et al., 1991, 1992; Järvelä, Mitchison, Callen, et al., 1995; Järvelä, Mitchison, O'rawe, et al., 1995; Lerner et al., 1994; Mitchison, O'Rawe, Lerner, et al., 1995; Mitchison, O’Rawe, Taschner, et al., 1995; Mitchison et al., 1994; Mitchison, Williams, et al., 1993; Mitchison, Thompson, et al., 1993) The final pieces of the puzzle were added by the International Batten Disease Consortium in 1995 (Batten Disease Consortium, 1995). Today, we know that the cytogenetic location of CLN3 is on the short arm of chromosome 16 at position 12.1 at Genomic coordinates chr16:28,466,653–28,492,302 [OMIM 607042] (NCBI gene entry, 1,201 (Järvelä, Mitchison, O'rawe, et al., 1995; Järvelä, Mitchison, Callen, et al., 1995; Mitchison, O'Rawe, Lerner, et al., 1995; Mitchison, Williams, et al., 1993).

Figure 1.

Linkage Mapping. The location of the gene responsible for JNCL was mapped to a region on chromosome 16. Initial findings placed the gene on the long arm of chromosome 16, due to its linkage with the haptoglobin (HP) locus. Later, the location of CLN3 was narrowed down to markers tagging the 16p11.2 region. The dinucleotide marker D16S298 is located in an intron of the CLN3 gene and thus represents the true location of CLN3

In 1997, Mitchison and colleagues reported the genomic structure and complete nucleotide sequence of CLN3, with an estimated number of 15 exons that span 15 kilobases (kb), (Mitchison et al., 1997). Sequence comparisons between CLN3 and homologous expressed sequence tags suggest alternative splicing of the gene and at least 1 additional upstream exon. Marker loci in strong allelic association with the disease loci have been identified (Mole & Gardiner, 1991).

Haplotype analysis identified a homozygous deletion mutation of 966 base pairs (bps) in 73% of 200 affected JNCL patients from 16 different countries (Mitchison, O'Rawe, Lerner, et al., 1995; Mitchison, Thompson, et al., 1993). This deletion mutation was originally believed to stretch 1.02 kb (Batten Disease Consortium, 1995). As a result, many reviews and primary articles refer to this deletion as the “1.02 kb” deletion. However, it was later confirmed that the common deletion spans 966 bps and is therefore more appropriately called the “1 kb” deletion. Cultured fibroblasts from a JNCL patient homozygous for the common 1 kb deletion have been shown to express a major transcript of 521 bps and a minor transcript of 408 bps (Kitzmüller, Haines, Codlin, Cutler, & Mole, 2008). The major transcript contains exon 6 spliced to exon 9 and is thought to encode a truncated CLN3 protein containing the first 153 amino acids of CLN3 plus an additional 28 novel amino acids resulting from an out‐of‐frame RNA sequence at the novel splice site. This gives rise to the following mutant protein sequence:

| 1 | MGGCAGSRRRFSDSEGEETVPEPRLPLLDHQGAHWKNAVGFWLLGLCNNFSYVVMLSAA | 60 |

| 61 | DILSHKRTSGNQSHVDPGPTPIPHNSSSRFDCNSVSTAAVLLADILPTLVIKLLAPLGLH | 120 |

| 121 | LLPYSPRVLVSGICAAGSFVLVAFSHSVGTSLCAISCCSHLLRPRTLEGKKKQRAQPGSP | 180 |

| 181 | S | 181 |

(Underlined letters indicate truncated first 153 AAs of CLN3 followed by 28 novel AAs due to a frameshift at the novel splice site). It is important to note that there is an S written in error at position 166 in some GenBank entries (GenBank: EF587245/1 and publications (Kitzmüller et al., 2008). This should be a “T” as shown above in yellow highlight (GenBank accession no AF077964 and AF077968, which are consistent with genomic sequence NG 008654.2).

2.2. CLN3 gene details

The full name of the gene is ceroid‐lipofuscinosis, neuronal 3, also known by the following symbols (CLN3, BTS, and JNCL). Gene product names include Batten disease protein, Batten, and Battenin. CLN3 gene product deficiency results in a rare, fatal inherited disorder of the nervous system that typically begins in childhood. The first symptom is usually progressive vision loss in previously healthy children followed by personality changes, behavioral problems and slow learning. Seizures commonly appear within 2–4 years of vision loss. However, seizures and psychosis can appear at any time during the course of the disease. Progressive loss of motor functions (movement and speech) start with clumsiness, stumbling and Parkinson‐like symptoms; eventually, those affected become wheelchair‐bound, are bedridden, and die prematurely. [see “CLN3‐Clinical Data.” The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (Batten disease). Ed. Mole, S.E., Williams R.E., Goebel H.H., Machado da Silva G., Cary, North Carolina, Oxford University Press, 2011. Pages 117–119. Print].

The most common name for the disease is Batten disease which was first used to describe the juvenile and presumably the CLN3 form (prior to the discovery of the gene). Today the term Batten is widely used in the US and UK to refer to all 13 forms of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The disease has also been called Batten‐Mayou disease, Batten‐Spielmeyer‐Vogt disease, CLN3‐related neuronal ceroid‐lipofuscinosis, juvenile Batten disease, Juvenile cerebroretinal degeneration, juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, Spielmeyer‐Vogt disease and the term adopted in 2012, CLN3 disease. Using the Basic Local Alignment Search (BLAST) tool to align regions of similarity between known biological sequences, investigators discovered that the CLN3 gene is highly conserved amongst Homo sapiens, Canis Lupus familiaris, Mus musculus, Danio rerio, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Schizosaccharomyces cerevisiae, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Altschul et al., 1997; Katz et al., 1999; Mitchell, Porter, Kuwabara, & Mole, 2001; Pearce & Sherman, 1997). The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene lists 179 orthologs discovered through comparison of known sequences.

2.3. Exon and Intron structure and alternative splice variants of CLN3

The CLN3 gene on the p‐arm of chromosome 16 spanning bases 28,466,653 to 28,492,302 http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGene?db=hg19%26hgg_gene=CLN3 (Haeussler et al., 2019; Kent et al., 2002) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/view/ (version 1.5.6 last update July 17, 2017). The CLN3 protein coding sequence begins on exon two at base 544 and ends at the final exon of the mRNA.

The NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq) database reports six transcript variants for the CLN3 gene suggesting that alternative splicing affects exons and the 3′ and 5′ UTRs (Untranslated Region;(Kent et al., 2002; Pruitt et al., 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/view/; version 1.5.6 last update July 17, 2017) of the genomic sequence. Most of the six isoforms contain between 13 and 16 exons; however, shorter isoforms are also reported in the Consensus CDS Protein Set. CLN3 isoform a consists of 438 amino acids (aa), and is encoded by the longest transcript variant 1 (NM_001042432.1) (Barnett, Pickle, & Elting, 1990) and 2 (NM_000086.2), 1915 bp and 1879 bp, respectively. Transcript variant 3 (NM_001286104.1) encodes for isofom b (NP_001273033.1) which lacks an alternate in‐frame exon resulting in a shorter protein of 414 aas. Variant 4 (NM_001286105.1) encodes for isoform c (NP_001273034.1) which begins with a downstream AUG (start codon) in the 5′UTR resulting in a different N‐terminus. Isoform c also lacks two exons, which gives rise to a truncated version of the protein consisting of only 338 aas. Isoform d (NP_001273038.1) encoded by transcript variant 5 (NM_001286109.1) contains variations in both 5′ and 3′ UTRs and lacks an in‐frame exon resulting in translation initiation at a downstream AUG and resultant protein of 360 aas. Similarly, isoform e (NP_001273039.1) encoded by variant 6 (NM_001286110.1) harbors alterations in the 5′ UTR and lacks an in‐frame exon leading to a delay in the initiation of translation and produces a protein of 384 aas.

RefSeq records are generated when there is experimental or published evidence in support of the full‐length product, whereas transcript alignments to the assembled genome indicate the possibility of a gene product. RefSeq records list 6 transcripts whereas Ensembl, which is not limited to proven transcripts, lists 64 potential transcripts for the CLN3 gene, providing additional clues to CLN3’s spatiotemporal patterns of expression. However, neither tissue, development, nor disease‐specific studies have been completed to indicate which transcripts are expressed under various conditions (Zerbino et al., 2018).

2.3.1. Impact of splice variants and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms on the protein domain structure of CLN3

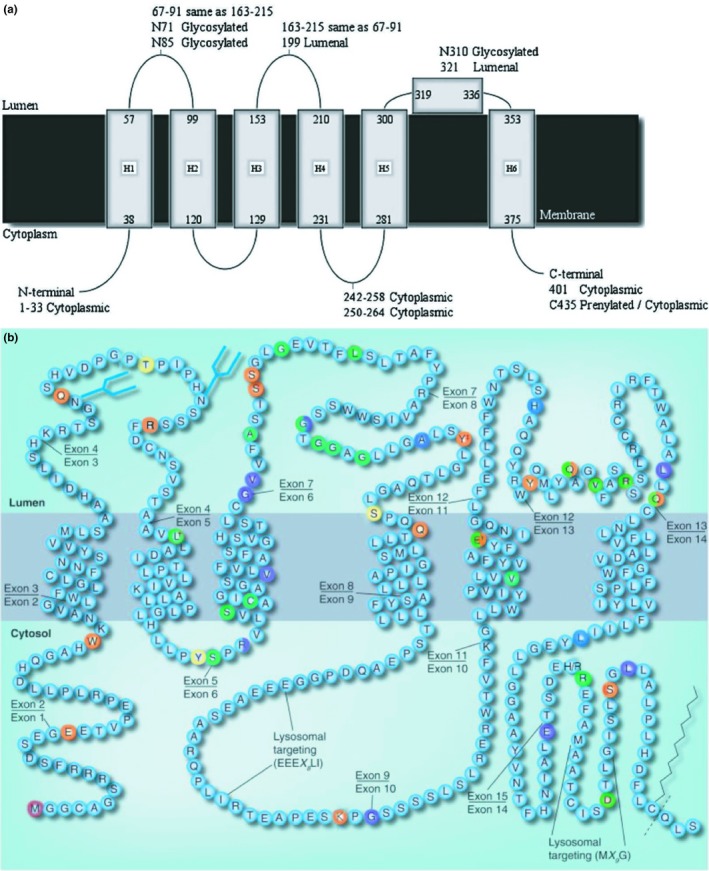

Interestingly, mapping the mutations causative of Batten Disease on a CLN3 topological model reveals that most of these mutations face the luminal side of the intracellular compartments. Moreover, evolutionarily constrained analysis of the aa sequence revealed that luminal loop 2, is the most highly conserved domain across species (Gachet, Codlin, Hyams, & Mole, 2005; Muzaffar & Pearce, 2008). Of particular note, the most common mutation found in CLN3 disease patients, the “1kb” deletion in which exons 7 and 8 are excised, maps within this loop. Similar to the second loop, the predicted amphipathic helix on the luminal face between the fifth and sixth transmembrane helices contains several missense mutations (Figure 2) (Kousi, Lehesjoki, & Mole, 2012; Nugent, Mole, & Jones, 2008). The clustering of a majority of missense mutations in these two luminal regions strongly suggests that they are critical sites for CLN3 protein interaction and function (Cotman & Staropoli, 2012).

Figure 2.

2a and 2b: 2a Schematic model for human CLN3 showing the six transmembrane helices, proposed amphipathic helix and experimentally determined loop locations. 2b The predicted topology of CLN3 is depicted. Sites for post‐translational modifications are shown as blue forked lines for N‐glycosylation, zigzags for prenylation, and dotted lines for potential cleavage sites following prenylation. Disease‐causing mutations are colored in red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. If the mutation covers multiple residues, only the first residue is marked. (NB‐All disease‐causing mutations are not shown. For a completes list see Table 1)

Mutations in CLN3 are classically associated with CLN3 disease where retinal degeneration is followed by mental and physical deterioration and premature death. Recent studies show that CLN3 mutations may also result in a nonsyndromic retinal degeneration whose onset differs considerably from classical Batten disease. CLN3 joins a growing number of genes such as TTC8, BBS2, and USH2A, whose mutations are commonly associated with syndromic diseases that include a subset of patients with isolated vision loss. Some mutations, as in the case of CLN3, can result in either phenotype (see Table 1) (Goyal, Jäger, Robinson, & Vanita, 2016; Rivolta, Sweklo, Berson, & Dryja, 2000; Shevach et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Representation of reported disease‐causing mutations, their associated regions of the DNA (i.e. promoter, coding, noncoding), cDNA change, genomic DNA change, protein change, type of mutation, human phenotype (CLN3 disease or nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa). Adapted from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ncl/CLN3mutationtable.htm

| Amino Acid position | Mutation location | cDNA Change | Genomic DNA change | Protein change | Type of mutation | Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter | c.‐1101C>T | g.28504365G>A | p.(=) | Sequence variant | Kousi et al. (2012) | ||

| Promoter | c.‐681_‐676delTGAAGC | g.28503756_28503761delGCTTCA | p.(?) | Sequence variant | Kousi et al. (2012) | ||

| 1 | Exon 1 | c.1A>C | g.28503080T>G | p.? | Missense or aberrant start | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 17 | Exon 2 | c.49G>T | g.28502879C>A | p.(Glu17*) | Nonsense | Kwon et al. (2005) | |

| 35 | Exon 2 | c.105G>A | g.28502823C>T | p.(Trp35*) | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| Exon 2 | c.125+1G>C | g.28502794C>G | p.? | splice defect | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Wang et al. (2014) | |

| Intron 2 | c.125+5G>A | g.28502798C>T | p.? | splice defect | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| Intron 2 | c.126‐1G>A | g.28500708C>T | p.? | splice defect | CLN3 Disease | Mole et al. (2001) | |

| 72 | Exon 3 | c.214C>T | g.28500619G>A | p.(Gln72*) | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| Intron 3 | c.222+2T>G | g.28500609A>C | p.? | Splice site | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| Intron 3 | c.222+5G>C | g.28500606C>G | p.? | Splice site | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 80 | Exon 4 | c.233_234insG | g.28499972_28499973insC | p.(Thr80Asnfs*12) | Frameshift | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 89 | Exon 4 | c.265C>T | g.28499941G>A | p.(Arg89*) | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease | Pérez‐Poyato et al. (2011) |

| 101 | Exon 5 | c.302T>C | g.28499055A>G | p.(Leu101Pro) | Missense | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Munroe et al. (1997) |

| 124 | Exon 5 | c.370dupT | g.28498987dup | p.(Tyr124Leufs*36) | Frameshift, introducing a premature stop codon | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| Exon 5 intron or Exon 6 | c.375‐3C>G | p.(?) | splice | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Ku et al. (2017) | ||

| 127 | Exon 6 | c.378_379dupCC | g.28498856_28498857dup | p.(Arg127Profs*55) | 1‐bp deletion and 2bp insertion | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012); Munroe et al. (1997) |

| 127 | Exon 6 | c.379delC | g.28498858delG | p.(Arg127Glyfs*54) | 1‐bp deletion | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 131 | Exon 6 | c.391A>C | g.28498828T>G | p.(Ser131Arg) | Missense | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Wang et al. (2014) |

| 134 | Exon 6 | c.400T>C | g.28498837A>G | p.(Cys134Arg) | Missense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 142 | Exon 6 | c.424delG | g.28498813delC | p.(Val142Leufs*39) | 1‐bp deletion | CLN3 Disease | Bensaoula et al. (2000), Kousi et al. (2012) and Munroe et al. (1997) |

| maximum deletion of intron 5–15, Minimum deletion of exon 8–15; | c.432+?_1350‐?del | g.28488804_28498805del | 6‐kb deletion | CLN3 Disease | Mitchison, O’Rawe, et al. (1995) | ||

| Intron 6 | c.461‐1G>C | g.28497972C>G | p.? | Splice defect | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| Intron 6 | c.461‐3C>G | p.(?) | splice | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Ku et al. (2017) | ||

| 154 | Intron 6 ‐ Intron 8 | c.461‐280_677+382del966 | g.28497286_28498251del | p.[Gly154Alafs*29, Val155_Gly264del] | (966 b deletion) | Batten Disease Consortium (1995), Munroe et al., (1997), Wisniewski, Zhong, et al. (1998), Zhong et al. (1998), Lauronen et al. (1999), Eksandh et al., 2000, Bensaoula et al., 2000, Teixeira et al. (2003), de los Reyes et al. (2004), Leman, Pearce, and Rothberg (2005), Kwon et al. (2005), Moore et al. (2008), Pérez‐Poyato et al. (2011), Kousi et al. (2012) and Ku et al. (2017) | |

| 154 | Intron 6 ‐ Intron 8 | c.461‐280_677+382del966 | g.28497286_28498251del | p.[Gly154Alafs*29, Val155_Gly264del] | (966 b deletion) | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Ku et al. (2017) |

| 155 | Intron 6 | c.461‐13G>C | g.28497984C>G | p.[=, Val155Profs*2] | Aberrant splicing that removes exon 7 | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997) |

| 158 | Exon 7 | c.472G>C | g.28497960C>G | p.(Ala158Pro) | Missense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 161 | Exon 7 | c.482C>G | g.28497950G>C | p.(Ser161*) | Nonsense | Munroe et al. (1997) | |

| 162 | Exon 7 | p.(Ser162*) | Nonsense | Munroe et al. (1997) | |||

| 165 | Exon 7 | c.494G>A | p.(Gly165Glu) | Missense | Cortese et al. (2014) | ||

| 170 | Exon 7 | c.509T>C | g.28497923A>G | p.(Leu170Pro) | Missense | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Munroe et al. (1997) |

| Intron 7 | c.533+1G>C | g.28497898C>G | p.? | Splice defect/frameshift | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Batten Disease Consortium (1995), Lauronen et al. (1999) and Munroe et al. (1997) | |

| Intron 7 | c.533+1G>A | g.28497898C>T | p.? | Splice site | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 187 | Exon 8 | c.558_559delAG | g.28497786_28497787delCT | p.(Gly187Aspfs*48) | 2‐bp deletion and Missense | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997) |

| 187 | Exon 8 | c.560G>C | g.28497785C>G | p.(Gly187Ala) | Missense | CLN3 Disease | Mole et al. (2001) and Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 189 | Exon 8 | c.565G>C | g.28497780C>G | p.(Gly189Arg) | Missense | CLN3 Disease and Non‐syndromic retinal dystrophy | Kousi et al. (2012) and Wang et al. (2014) |

| 189 | Exon 8 | p.(Gly189Arg) | Missense | CLN3 Disease and Non‐syndromic retinal dystrophy | Kousi et al. (2012); Wang et al. (2014) | ||

| 192 | Exon 8 | c.575G>A | g.28497770C>T | p.(Gly192Glu) | Missense | CLN3 Disease | Pérez‐Poyato et al. (2011) |

| Exon 8 | c.582G>T | g.28497763C>A | p.(=) | Sequence variant | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Sarpong et al. (2009) | |

| 196 | Exon 8 | c.586dupG or c.586‐587insG | g.28497759dup | p.(Ala196Glyfs*40) | 1‐bp insertion | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997) |

| 199 | Exon 8 | c.597C>A | g.28497748G>T | p.(Tyr199*) | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Sarpong et al. (2009), Kousi et al. (2012) and Mole et al. (2001) |

| 208 | Exon 8 | c.622dupT | g.28497723dup | p.(ser208Phefs*28) | Frameshift, introducing a premature stop codon | Kousi et al. (2012) and Pérez‐Poyato et al. (2011) | |

| 211 | Exon 8 | c.631C>T | g.28497714G>A | p.(Gln211*) | Nonsense | Munroe et al. (1997) | |

| Intron 8 | c.678‐?_1317+?del | g.28488837‐?_28495439+?del | p.? | partly characterised deletion | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 262 | Exon 9 | c.784A>T | p.(Lys262*) | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease | Coppieters et al. (2014) | |

| Intron 9 | c.790+3A>C | g.28495324T>G | p.? | Sequence Variant | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 264 | Intron 9 ‐ Intron 13 | c. 791_1056del | g.28491981_28494795del2815 | p.(Gly264Valfs*29) | 2.8‐kb deletion | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Batten Disease Consortium (1995), Munroe et al. (1997), Lauronen et al. (1999), Kousi et al. (2012) and Mole et al. (2001) |

| 155 | Exon 10 | c.831G>A | g.28493953C>T | p.[Val155_Gly264del, Gly280_Leu302del] | Sequence variant | CLN3 Disease | Zhong et al. (1998) |

| Exon 10 intron or Exon 11 | c.837+5G>A | p.(?) | splice | CLN3 Disease and Non‐syndromic retinal dystrophy | Ku et al. (2017) | ||

| 285 | Exon 11 | g.28493851T>C | p.(Ile285Val) | missense | CLN3 Disease and Non‐syndromic retinal dystrophy | Carss et al. (2017) and Ku et al. (2017) | |

| 290 | Exon 11 | c.868G>T | p.(Val290Leu) | Missense | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Wang et al. (2014) | |

| 295 | Exon 11 | c.883G>A | g.28493821C>T | p.Glu295Lys | Missense and Nonsense | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Lauronen et al. (1999), Munroe et al. (1997), Wang et al. (2014) and Zhong et al. (1998) |

| 295 | Exon 11 | c.883G>T | g.28493821C>A | p.(Glu295*) | nonsense | CLN3 Disease and Non‐syndromic retinal dystrophy | Kousi et al. (2012), Ku et al. (2017) and Mole et al. (2001) |

| Intron 11 | c.906+5G>A | g.28493793C>T | splice defect | Splice site | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 306 | Exon 12 | c.917T>A | p.(Leu306His) | missense | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Ku et al. (2017) | |

| Exon 12 | c.944‐945insA | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997) | ||||

| 313 | Exon 12 | c.954_962+18del27 | g.28493630_28493656del27 | p.Leu313_Trp321del/ splice defect | Splice defect | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 315 | Exon 12 | c.944dupA | g.28493666dup | p.(His315Glnfs*67) | 1‐bp insertion | CLN3 Disease | Licchetta et al. (2015) |

| Exon 12 | c.10633‐10660del | Frameshift after Q318, possible aberrant splicing | Mole et al. (2001) | ||||

| Exon12‐Intron12 | c.963‐1G>T | g.28493520C>A | p.? | Splice defect | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 322 | c.966C>G | p.(Tyr322*) | Nonsense | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Wang et al. (2014) | ||

| 330 | Exon 13 | c.988G>A | g.28493494C>T | p.(Val330Phe) | Missense | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Carss et al. (2017) and Ku et al. (2017) |

| 334 | Exon 13 | c.1000C>T | g.28493482G>A | p.Arg334Cys | Missense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) and Munroe et al. (1997) |

| 334 | Exon 13 | c.1001G>A | g.28493481C>T | p.Arg334His | Missense | CLN3 Disease, protracted | Batten Disease Consortium (1995), Kousi et al. (2012), Munroe et al. (1997) and Pérez‐Poyato et al. (2011) |

| 349 | Exon 13 | c.1045_1050del | p.(Ala349_Leu350del) | 6‐bp deletion | CLN3 Disease | Licchetta et al. (2015) | |

| 350 | Exon 13 | c.1048delC | g.28493434delG | p.Leu350CysfsX27 | 1‐bp deletion | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 352 | Exon 13 | c.1054C>T | g.28493428G>A | p.Gln352X | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) and Munroe et al. (1997) |

| Intron 13 | c.1056+3A>C | g.28493423T>G | p.? | Splice site | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) | |

| 379 | Exon 14 | c.1135_1138delCTGT | p.(Leu379Metfs*11) | 4‐bp insertion | CLN3 Disease | Drack, Miller, and Pearce (2013) | |

| 399 | Exon 14 | c.1195G>T | g.28489060C>A | p.(Glu399*) | 27‐bp deletion | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 400 | Intron 14 | c.1198‐1G>T | g.28488957C>A | p.Thr400* | Splice site | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997); Mole et al. (2001) |

| 404 | Exon 15 | c.1211A>G | g.28488943T>C | p.(His404Arg) | Polymorphism | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997) and Mole et al. (2001) |

| 405 | Exon 15 | c.1213C>T | g.28488945G>A | p.(Arg405Trp) | Missense | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Carss et al. (2017), Ku et al. (2017), Wang et al. (2014) and Weisschuh et al. (2016) |

| 416 | Exon 15 | c.1247A>G | g.28488907T>C | p.(Asp416Gly) | Missense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 423 | Exon 15 | c.1268C>A | g.28488886G>T | p.(Ser423*) | Nonsense | CLN3 Disease | Kousi et al. (2012) |

| 425 | Exon 15 | c.1272delG | g.28488882delC | p.(Leu425Serfs*87) | 1‐bp deletion | CLN3 Disease | Munroe et al. (1997) |

| g.28497285‐28498251del | NA | large deletion | Non‐syndromic retinal disease | Carss et al. (2017) |

2.4. CLN3 gene regulation

The CLN3 gene was sequenced in 1997 following the discovery of the protein. Sequencing began 1.1 kb upstream of the transcription start site and proceeded to 0.3 kb downstream of the polyadenylation site. Sequencing led to the conclusion that CLN3 is organized into at least 15 exons spanning 15 kb ranging from 47 to 356 bps in length (Mitchison et al., 1997). CLN3 also has 14 introns that vary from 80 to 4,227 bps in length. There are a total of 12 Alu repeats in the forward orientation and 9 in reverse orientation present within the introns and 5′‐ and 3′‐untranslated regions. The 5′ region of the CLN3 gene contains several potential transcription regulatory elements. Although there are two (TA)n repetitive motifs at nt 135 and 335 in the sequence, there is no consensus TATA‐1 box evident, suggesting that CLN3 is constitutively expressed (Mitchison et al., 1997). In addition, using the transcription factor DNA binding site database, putative cis‐acting regulatory elements were found in the 5′ flanking sequence, including potential transcription factor binding sites for AP‐1, AP‐2, and Sp1, two motifs for the erythroid‐specific transcription factor GATA‐1 and three potential CCAAT boxes (Mitchison et al., 1997).

2.4.1. CLN3 promotor and transcription factor binding analysis

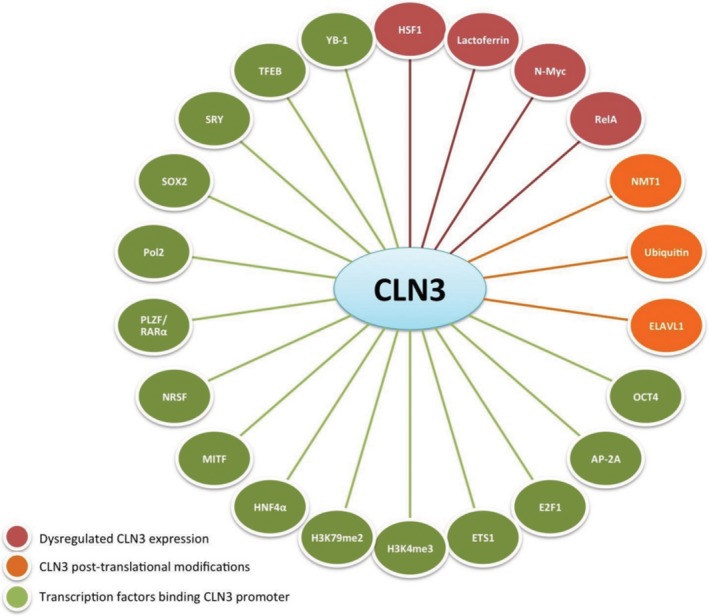

Several regulatory elements have been found in the 5′ region of the CLN3 gene; however, the endogenous promoter of CLN3 has not been definitively characterized yet. To this end, Eliason and colleagues created transgenic CLN3 mice by knocking‐in a DNA sequence encoding for nuclear‐targeted bacterial β‐gal. This was achieved via homologous recombination of a targeting construct into embryonic stem cells, such that β‐gal transcription was controlled by a native sequence 5′ to the CLN3 coding region. This resulted in the replacement of most of exon 1 and all of exons 2–8, creating an effective null mutation (Ding, Tecedor, Stein, & Davidson, 2011; Eliason et al., 2007). In these studies, the authors demonstrated that CLN3 is ubiquitously expressed and that a regulatory and functional region at the 5′ of the gene is promoting its expression. Other studies have described a putative promoter region and identified predicted transcription factor binding sites (see Table 2 for complete list). Moreover, a multitude of transcription factors have been reported to regulate CLN3 expression pattern by direct interaction (physical binding) with the “promoter” region or by indirect interaction through protein partners. Indeed, TFEB has been shown to bind to CLEAR elements on the proximal promoter of CLN3, which increases CLN3 transcription (Palmieri et al., 2011; Sardiello et al., 2009). TFEB binding sites were first mapped to −24 (AGCACGTGAT) and +6 (GTCACGTGAT) on the promoter of CLN3 (Sardiello et al., 2009) and physical binding of TFEB was then further experimentally verified by ChIP‐seq (Palmieri et al., 2011). Table 2 reports nonredundant transcription factor interactor of CLN3 that regulate its expression profile. Additional information on each interaction, that is, the type of experimental support and key functional statement, is provided below.

Table 2.

Transcriptional regulators of CLN3

| Putative Transcriptional Regulator | Protein details | Putative effect | Methods used to identify putative transcriptional regulator | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP‐2A | Putative CLN3 promoter has an AP‐2A binding site. | Putative CLN3 promoter has an AP‐2A binding site. | The authors developed a computational genomics strategy termed ChIPModules which begins with experimentally‐determined binding sites and integrates those with positional weight matrices constructed from transcription factor binding sites, comparative genomics, and statistical learning methods with the purpose of identifying transcriptional regulatory modules. They identify that the putative CLN3 promoter contains an AP‐2alpha binding site | Jin, Rabinovich, Squazzo, Green, and Farnham (2006) |

| E2F1 | E2F1_HUMAN | Putative CLN3 promoter has a putative E2F1 binding site. | Researchers studied the binding of E2F1 to promoters. ChIP analyses of 24,000 promoters confirmed that more than 20% of promoters are bound by E2F1. Including the CLN3 promoter | Bieda, Xiaoqin, Singer, Green, and Farnham (2006) |

| ELAV1 (huR)E2F1 | E2F1_HUMAN | Putative CLN3 promoter has a putative E2F1 binding site. | HuR regulates the stability and translation of numerous mRNAs encoding for stress response and proliferative proteins. HuR was found to bind CLN3 mRNA. The interaction value was higher than the mock controls; albeit very weak. Researchers studied the binding of E2F1 to promoters. ChIP analyses of 24,000 promoters confirmed that more than 20% of promoters are bound by E2F1. Including the CLN3 promoter | Abdelmohsen et al. (2009); Bieda et al. (2006) |

| ETS1ELAV1 (huR) | ETS1 Human | ETS1 binds to the putative CLN3 promoter | The CLN3 promoter contains putative ETS1 binding motifs. HuR regulates the stability and translation of numerous mRNAs encoding for stress responses and proliferative proteins. HuR was found to bind CLN3 mRNA. The interaction value was higher than the mock controls; albeit very weak. | Hollenhorst et al. (2009); Abdelmohsen et al. (2009) |

| ETS1ETS1 | ETS1 MouseETS1 Human | ETS1 binds to the putative CLN3 promoter | CLN3 is downregulated in ETS1‐/‐ mNK cells. The CLN3 promoter contains putative ETS1‐binding motifs. | Ramirez et al. (2012); Hollenhorst et al. (2009) |

| HNF4‐alphaETS1 | HNF4A_HUMANETS1 Mouse | HNF4‐alpha binds to gene CLN3 promoterETS1 | In the referenced paper, CLN3 appears in a list of potential HNF4alpha target genes in differentiated Caco2 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. CLN3 is downregulated in ETS1‐/‐ mNK cells | Bolotin et al. (2010), Boyd, Bressendorff, Møller, Olsen, and Troelsen (2009) and Ramirez et al. (2012) |

| HSF1HNF4‐alpha | HSF1_HUMANHNF4A_HUMAN | CLN3 harbors an HSF 1 site I at a proximal Alu in an antisense orientationHNF4‐alpha binds to gene CLN3 promoter | CLN3 is downregulated upon heat shock in microarray experiments. In the referenced paper, CLN3 appears in a list of potential HNF4alpha target genes in differentiated Caco2 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. | Bolotin et al. (2010), Boyd et al. (2009) and Pandey, Mandal, Jha, and Mukerji (2011) |

| TFEB | CLEAR | CLN3 harbors a two CLEAR binding site on its proximal promoter (at −24 nad +6). | TFEB has been shown to bind this (CLEAR) element in the proximal promoter of CLN3 and increase CLN3 transcription. | Palmieri et al. (2011) and Sardiello et al. (2009) |

Additionally, transcription factor binding sites were predicted for the CLN3 promoter using the sequence‐based profiles of known sites. Position‐specific scoring matrices were applied for 202 human transcription factors or factor dimers obtained from the JASPAR database (Portales‐Casamar et al., 2010). The promoter region of CLN3 was obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser using the RefSeq gene boundaries (Pruitt et al., 2014). A 1‐kb region upstream and 500 bases downstream of the transcription start site (TSS) were used for this analysis. The motif search was performed using the MAST tool from the MEME suite (Bailey et al., 2009).

The complete list of predicted transcription factor binding sites is shown in Table 3. Interestingly, the transcription factors SP2, ESRRA, Klf4, and USF2 each have three or more predicted binding sites in the vicinity of the transcription start site of CLN3.

Table 3.

Predicted transcription factor binding sites on the CLN3 gene

| Position Relative to TSS | Transcription factor | p‐value | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| −329/−123 | E2F3 | 6.9E‐05/5.6E‐07 | 14 |

| −323 | E2F4 | 8.50E‐05 | 10 |

| −734 | EGR2 | 5.90E‐05 | 14 |

| −549 | ELF1 | 3.40E‐06 | 12 |

| −1,396 | ESR1 | 3.50E‐05 | 19 |

| −1,344/−672/−214 | ESRRA | 7.4E‐05/‐9.10E‐05/3.05E‐05 | 10 |

| −919 | FOXA1 | 1.40E‐06 | 14 |

| −915 | Foxa2 | 8.20E‐08 | 11 |

| −131 | FOXC1 | 5.00E‐05 | 7 |

| −1,276 | Foxd3 | 3.20E‐05 | 11 |

| −777 | FOXI1 | 9.80E‐05 | 11 |

| −1,469/−1,271/−807 | FOXP1 | 3.7E‐05/2.2E‐05/3.00E‐05 | 14 |

| −545 | GABPA | 5.50E‐06 | 10 |

| −1,364 | Gata4 | 4.40E‐05 | 10 |

| −603/−407/−388 | Klf4 | 1.4E‐05/3.60E‐05/5.00E‐07 | 9 |

| −1,222 | Meis1 | 9.90E‐05 | 14 |

| −83 | NHLH1 | 7.50E‐05 | 11 |

| −1,349/−677 | NR2F1 | 5.4E‐05/2.00E‐05 | 13 |

| −172 | NRF1 | 9.60E‐05 | 10 |

| −495 | Pax2 | 9.70E‐05 | 7 |

| −1,468 | Pax4 | 2.80E‐05 | 29 |

| −1,493/−1,102 | PAX5 | 2.2E‐06/4.40E‐05 | 18 |

| −1,317 | PBX1 | 4.60E‐05 | 11 |

| −230 | PLAG1 | 1.60E‐06 | 13 |

| −1,285 | POU2F2 | 3.90E‐05 | 12 |

| −1,253 | PRDM1 | 8.20E‐06 | 14 |

| −1,136 | Rfx1 | 7.60E‐05 | 13 |

| −1,167 | RFX5 | 6.30E‐05 | 14 |

| −603/−412/−393/−123 | SP2 | 1.30E‐05/1.90E‐05/6.80E‐05/4.60E‐06 | 14 |

| −715/−305 | Tcfcp2l1 | 8.90E‐05/5.70E‐05 | 13 |

| −1,409/−434 | TFAP2C | 5.70E‐05/1.60E‐05 | 14 |

| −711 | THAP1 | 4.60E‐05 | 8 |

| −308 | TP63 | 2.70E‐05 | 19 |

| −786/−494/−267 | USF2 | 8.00E‐05/7.60E‐06/7.20E‐05 | 10 |

| −242 | ZBTB33 | 8.80E‐05 | 14 |

| −83 | ZEB1 | 4.80E‐05 | 8 |

| −433 | Zfx | 2.60E‐05 | 13 |

Transcription Factors from MetaCore from Clarivate Analytics (Ekins, Nikolsky, Bugrim, Kirillov, & Nikolskaya, 2007).

In addition to regulation by transcription factors, studies have demonstrated that various molecules can indirectly regulate the expression of CLN3. These are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Alternative transcriptional regulation

| Alternative Transcription Regulator | Protein details | Methods used to Identify Putative Transcriptional Regulator | PubMed ID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LactoferrinHSF1 | TRFL_HUMAN DeltaLfHSF1_HUMAN | CLN3 harbors an HSF 1 site I at a proximal Alu in an antisense orientation | One form of LF is secreted in body fluids (sLF) whereas an alternative form deltal LF, regulated by a different promoter, is present in normal tissues. Delta LF is downregulated in breast cancer. The CLN3 promoter is downregulated in delta LF expressing HEK cell upon heat shock in microarray experiments. | Kim, Kang, and Kim (2013) and Pandey et al. (2011) |

| MITFLactoferrin | MITF_HUMANTRFL_HUMAN DeltaLf | MITF interacts with the putative CLN3 promoter | Putative CLN3 promoters have been pulled down by gene‐wide chromatin immunoprecipitation of MITF. One form of LF is secreted in body fluids (sLF) whereas an alternative form deltal LF, regulated by a different promoter, is present in normal tissues. Delta LF is downregulated in breast cancer. CLN3 is downregulated in delta LF expressing cell's.promoter. | Bertolotto et al. (2011) and Kim et al. (2013) |

| N‐MyristoylationN‐Myc | N‐myristoyltransferase_(HUMAN)MYCN_MOUSE | N‐Myc regulates transcription of CLN3 | Using SILAC, researchers found that CLN3 is N‐myristoylated. The authors studied changes in gene expression in embryonic stem cells after the induction of various transcription factors. CLN3 was included in the analyses. | Chen et al. (2008) and Nishiyama et al. (2009) |

2.5. Description of the CLN3 protein

The CLN3 gene encodes a highly hydrophobic protein of 438‐amino acids, the three‐dimensional structure of which has not yet been proven through X‐ray crystallography or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance‐spectroscopy. The secondary structure of CLN3 is mainly comprised of transmembrane and low complexity cytosolic or luminal spans (Berman et al., 2000). Computer prediction models suggest CLN3 spans the membrane anywhere from five to ten times (SPEP + Ensemble 1.0, MEMSAT3 + Swissprot, MEMSAT3, TMHMM 2.0, PHOBIUS Constrained, PROFPHD, HMMTOP). However, some experimental studies support a structure where the N‐terminus faces the intraluminal space of organelles with the C‐terminus facing the cytoplasm, the most widely cited peer‐reviewed articles favor a 6‐membrane spanning domain (MSD) model with both the N‐ and C‐termini facing the cytosol. See Figure 2 table below for more detailed information (Ezaki et al., 2003; Mao, Foster, Xia, & Davidson, 2003; Mao, Xia, & Davidson, 2003; Ratajczak, Petcherski, Ramos‐Moreno, & Ruonala, 2014).

Table 5.

Locations of experimentally determined regions/residues

| Region/residue | Location | References |

|---|---|---|

| N‐terminal | Cytoplasmic | Ezaki et al. (2003) and Ratajczak et al. (2014) |

| 1–33 | Cytoplasmic | |

| 2–18 | Lumenal | Mao, Foster, et al. (2003) and Mao, Xia, et al. (2003) |

| N71 | Lumenal | |

| N85 | Lumenal | Storch et al. (2007) |

| *97–121 | MSD | [SPEP + Ensemble 1.0, MEMSAT3, + Swissprot, MEMSAT3 + CLN3, TMHMM 2.0, PHOBIUS Constrained, PROFPHD, HMMTOP] |

| 199 | Lumenal | Mao, Foster, et al. (2003) |

| 210–231 | MSD | [SPEP + Ensemble 1.0, MEMSAT3, + Swissprot, MEMSAT3 + CLN3, TMHMM 2.0, PHOBIUS Constrained, PROFPHD, HMMTOP] |

| 250–264 | Cytoplasmic | Mao, Foster, et al. (2003) and Mao, Xia, et al. (2003) |

| 242–258 | Cytoplasmic | Kyttälä et al. (2004) |

| *276–303 | MSD | [SPEP + Ensemble 1.0, MEMSAT3, + Swissprot, MEMSAT3 + CLN3, TMHMM 2.0, PHOBIUS Constrained, PROFPHD, HMMTOP] |

| N310 | Lumenal | Mao, Foster, et al. (2003) and Storch et al. (2007) |

| 321 | Lumenal | Mao, Foster, et al. (2003) |

| S401 | Cytoplasmic | Kyttälä et al., (2004) and Ratajczak et al. (2014) |

| 406–433 | Cytopasmic | Nugent et al. (2008) |

| Cys435 | Cytoplasmic | Storch et al. (2007) |

| C‐terminal | Cytoplasmic | Mao, Xia, et al. (2003) and Ratajczak et al. (2014) |

Computer Modeling was included for MSDs for which all prediction models support the same conclusion.

2.6. CLN3 protein details

2.6.1. Consensus sequence elements similar to other proteins

The CLN3 protein sequence does not display significant similarities to any protein of known function (Muzaffar & Pearce, 2008). However, some consensus sequence elements within the CLN3 protein allude to its localization, regulation, and function. Early predictions of CLN3 using Position‐Specific Iterative Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (PSI‐BLAST) revealed a distant but significant sequence similarity between CLN3 and members of the SLC29 family of equilibrative nucleoside transporters, of which four members are recognized in mammals (Altschul et al., 1997; Baldwin et al., 2004). More recent algorithms, such as the Structural Classification of Proteins (Andreeva et al., 2008) and Protein families (Pfam) suggest that most of the CLN3 protein (aa 11–433) has a domain structure consistent with members of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS; SCOP superfamily 103473; Pfam clan CL0015). The MFS superfamily is one of the two largest families of membrane transporters and includes small‐solute uniporters, symporters and antiporters (Marger & Saier, 1993). Structural similarities between CLN3 and MFS family member MFSD8, may provide important clues as to its function. Indeed, mutations in MFSD8, which encodes a lysosomal protein with 12‐predicted transmembrane domains and unknown function, result in histological and phenotypical similarities to another form of Batten disease, CLN7, (Siintola et al., 2007). Moreover, sequence alignment and Markov modeling predicted the N‐terminus of CLN3 to be weakly homologous to fatty acid desaturases. Using nervous system and pancreatic tissue samples from a murine homozygous‐knockout model of CLN3, investigators demonstrated that Δ9 desaturase activity was greatly reduced, while heterozygous carriers displayed intermediate desaturase levels (40%) compared to wild‐type animals. Therefore, the loss of CLN3 appears to result in decreased desaturase activity on palmitoyl (C16) moieties of protein substrates (Narayan, Rakheja, Tan, Pastor, & Bennett, 2006; Narayan, Tan, & Bennett, 2008).

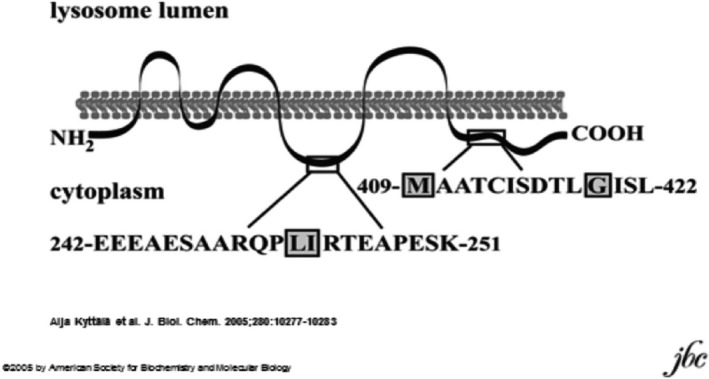

Sequence analysis also indicated a multitude of putative trafficking and sorting signals, suggesting CLN3 may populate a variety of organelles. A mitochondrial targeting signal was identified at residue 11 with a cleavage site at residue 19 (Janes et al., 1996). Furthermore, targeting studies demonstrated the existence of two lysosomal sorting signals; (a) a conventional dileucine motif preceded by an acidic patch located in a putative cytosolic loop of the favored 6‐transmembrane structure (Kyttälä et al., 2004) at 242EEE(X)8LI254 and (b) an unconventional motif in the long C‐terminal cytosolic tail consisting of methionine and glycine separated by nine amino acids [M(X)9G] (Kyttälä et al., 2005, 2004; Järvelä et al., 1998; Kida et al., 1999; Storch, Pohl, & Braulke, 2004). Interestingly, green fluorescent protein (GFP)‐tagged CLN3 with a double mutation in the dileucine motif (Leu425Leu426), a putative lysosomal targeting motif, to glycine (Gly425Gly426) still co‐localized with lysosomal associated membrane protein‐1 (LAMP1) in chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, suggesting that the dileucine motif is not required for the targeting of CLN3 to the lysosome. Since the dileucine motif is conserved among species, these results suggest that CLN3 contains additional lysosomal targeting sequences or different lysosomal targeting signals altogether (Kida et al., 1999). In contrast truncations of CLN3: GFP‐CLN3(1–322), GFP‐CLN3(138–438), and CLN3(1–138)‐GFP do not localize to lysosomes (Kida et al., 1999) indicating that the missing regions either contain imperative lysosome targeting signals or their absence alters the 3D structure of the protein.

Initial studies suggested that yeast CLN3 homolog Btn1 in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe localizes to yeast vacuoles (Croopnick, Choi, & Mueller, 1998; Gachet et al., 2005; Pearce, Ferea, Nosel, Das, & Sherman, 1999; Wolfe, Padilla‐Lopez, Vitiello, & Pearce, 2011). However, more recent studies suggest that experimental tags may have mislocalized the protein. Indeed, when not tagged at its C‐terminus, Btn1 localizes to the Golgi apparatus (Codlin & Mole, 2009; Dobzinski, Chuartzman, Kama, Schuldiner, & Gerst, 2015; Kama, Kanneganti, Ungermann, & Gerst, 2011; Vitiello, Benedict, Padilla‐Lopez, & Pearce, 2010).

2.6.2. Post‐translational modifications of the CLN3 protein

CLN3 contains several putative post‐translational modification (PTM) motifs which contribute to the targeting and anchoring of CLN3 to distinct biological membranes (Casey, 1995). These motifs include four putative N‐glycosylation sites, two putative O‐glycosylation sites, and consensus sequences for phosphorylation, myristoylation, and farnesylation (Ellgaard & Helenius, 2003; Golabek et al., 1999; Haskell, Carr, Pearce, Bennett, & Davidson, 2000; Järvelä et al., 1998; Kaczmarski et al., 1999; Kida et al., 1999; Mao, Xia, et al., 2003; Michalewski et al., 1998, 1999; Nugent et al., 2008; Pullarkat & Morris, 1997; Sigrist et al., 2013; Storch, Pohl, Quitsch, Falley, & Braulke, 2007; Taschner, de Vos, & Breuning, 1997b).

Glycosylation

Alignment and comparison of the CLN3 amino acid sequences across species (human, canine, murine, and yeast CLN3; Genbank Accession number U32680, L76281.1, U68064, AF058447.1) revealed a number of highly conserved N‐X‐S/T motifs, indicating conservation of putative glycosylation sites. In vitro translation of CLN3 produced a singlet at 43 kilodaltons (kDa) in the absence of microsomal membranes and a doublet at 43 and 45 kDa in the presence of microsomal membranes (using rabbit antibody 385/CLN3 raised against residues 242–258 [EEEAESAARQPLIRTEA], which map to the long cytosolic loop according to the most cited prediction model). Similarly, intracellular synthesis and maturation of CLN3 in COS‐1 and HeLa cells also identified the 43 kDa nonglycosylated and a 45 kDa glycosylated forms of CLN3. In detail, pulse‐chase of transfected COS‐1 cells followed by immunoprecipitation showed a single band of 43 kDa 1 hr following the pulse, while further chase up to 6 hr revealed a characteristic doublet of 43 and 45 kDa. Human N‐glycosylated CLN3 protein is sensitive to endoglycosidase H suggesting a high‐mannose type glycosylation (Järvelä et al., 1998). In contrast, murine CLN3 contains complex‐type N‐linked sugars that differ from the human CLN3 (Ezaki et al., 2003). Moreover, mass spectrometric analyses revealed that CLN3 exhibits tissue‐dependent glycosylation patterns (Ezaki et al., 2003). Thus, the apparent molecular weight of glycosylated CLN3 protein may vary depending on cell type and species (Golabek et al., 1999).

Expression of GFP‐CLN3 fusion protein resulted in a 66 and a 100 kDa bands in neuroblastoma and CHO cells, whereas in COS and HeLa cells only the 66 kDa band is detectable. Expression of GFP alone resulted in a 27kDa band, indicating that CLN3 alone would result in ~39 and ~73 kDa bands, respectively. Pulse‐chase experiments revealed that the 66 kDa form appears first, followed by the 100 kDa band. Both the 66 and 100 kDa forms are digested by complex oligosaccharide amidase Peptide ‐N‐Glycosidase F down to 64 kDa. Whereas glycosidase Endoglycosidase H only digests the 66 kDa form. Thus, the 100 kDa form is a complex oligosaccharide in some cell types (Golabek et al., 1999).

N‐linked glycosylation of integral membrane proteins in the ER and in the early secretory pathways, has been shown to be important for protein folding, oligomerization, quality control, sorting and function (Ellgaard & Helenius, 2003). Human CLN3 possesses four potential N‐glycosylation sites (N49, N71, N85, and N310). Glycosylation of N49 is physically unlikely because this residue is located in the first membrane domain. Mutational analyses demonstrated that N71 and N85, located in the first luminal domain, are N‐linked glycosylated (Storch et al., 2007). It remains unclear whether N310, in the third luminal domain, is N‐linked glycosylated (Mao, Foster, et al., 2003; Storch et al., 2007). N‐glycosylation is not required for the proper trafficking of CLN3, as neither treatment with the N‐glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin, nor single or double substitution of N71 and N85 affected the stability or the trafficking of CLN3 to lysosomes (Golabek et al., 1999; Kida et al., 1999; Storch et al., 2007).

CLN3 also possesses two putative O‐glycosylation sites at T80 and T256 (Consortium 1995). However, O‐glycosylation sites are poorly defined, not necessarily utilized, and T256 is predicted to be cytoplasmic, which is not compatible with glycosylation.

Phosphorylation

Sequence analyses using the ScanPROSITE tool (Sigrist et al., 2013) suggest that CLN3 contains nine putative phosphorylation sites: six on cytoplasmic loops (Ser12, Ser14, Thr19, Thr232, Ser270, Thr400) and three on luminal loops (Ser69, Ser74, Ser86) (Nugent et al., 2008). Previous computer‐based predictions identified 10 serine and 3 threonine residues that may undergo phosphorylation (Michalewski et al., 1998). GFP‐CLN3 expressed in CHO cells incorporates 32P in both the 66 and 100 kDa forms, when incubated with cAMP‐dependent protein kinase (PKA), cGMP‐dependent protein kinase (PKG) or casein kinase II. The reaction was reversed by alkaline phosphatase, indicating that GFP‐CLN3 is indeed phosphorylated (Michalewski et al., 1998, 1999) by PKA, PKG, and casein kinase II and can be enhanced by inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 or protein phosphatase 2A. However, as these studies relied solely on in vitro assays using kinase activators or phosphatase inhibitors, future studies based on protein knockdown in cellular systems will be useful to better assess the specificity and the biological role of each of these proteins in the regulation of CLN3. However, phosphorylation is important for multiple physiological functions such as membrane targeting, protein–protein interactions and the formation of functional complexes, the phosphorylation states and significance of CLN3 phosphorylation remain elusive. The generation of CLN3 phosphomutants would have merit for fully elucidating the biological relevance of these PTMs.

Myristoylation

A putative N‐myristoylation site exists at 2GGCAGS7 in human (Genbank Accession number U32680), canine (Genbank accession number L76281.1) and murine (Genbank Accession number U68064) CLN3. The significance of this lipid modification to CLN3 has not been explored experimentally. However, covalent attachment of myristoyl group by an amide bond to an alpha‐amino group of a N‐terminal glycine has been implicated in protein‐protein and protein‐lipid interactions, membrane targeting, and numerous signal transduction steps. Conservation of N‐myristoylation motifs in human, dog, and mouse as well as isoprenylation motifs in human, dog, mouse and yeast suggest that CLN3 could be a membrane‐attached protein despite the lack of a signaling peptide (Taschner, de Vos, & Breuning, 1997a).

Prenylation/Farnesylation

Prenylation refers to the addition of hydrophobic molecules to a substrate, and involves the transfer of either farnesyl or geranyl‐geranyl moiety to C‐terminal cysteine(s) of the target protein. It is believed that prenyl group modifications facilitate attachment to cell membranes, similar to lipid anchors. Farnesylation is a type of prenylation, where an isoprenyl group is added to a cysteine residue. These modifications are important for protein–protein and protein–membrane interactions. Sequence analyses of CLN3 predict a CAAX motif 435CQLS438 at the C‐terminus that can be prenylated (Taschner et al., 1997a). Coupled translation/prenylation reactions of CLN3 and tetra‐peptides in vitro demonstrate that the CQLS sequence acts as a good acceptor for a farnesylation group (Kaczmarski et al., 1999; Pullarkat & Morris, 1997). Furthermore, glutathione S transferase (GST)‐fusion CLN3 protein, and CLN3 synthesized in a cell‐free environment act as prenylation substrates. Prenylation of GST‐CLN3T greatly enhances its association with membranes. Since prenylation occurs at protein termini, this modification at the C‐terminus of CLN3 may create an additional, terminal loop, which contradicts the assumption that the C‐terminus is free‐floating in the cytosol (Kaczmarski et al., 1999). Substitution of C435 by C435S does not affect CLN3 exit from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or transport to lysosomes in COS7 cells but trafficking rate and sorting efficiency are affected (Storch et al., 2007). Incubation with increasing concentrations of farnesyltransferase inhibitor L‐744,832 prevented prenylation of CLN3, which resulted in an increase in the fraction of CLN3 at the plasma membrane, suggesting that C‐terminal lipid modification of CLN3 is important for proper sorting (Storch et al., 2007). It is important to note that while sequence similarities and short‐term in vitro experiments are helpful, no experimental data exists demonstrating the function of PTMs of CLN3 protein in vivo.

2.7. Biosynthesis, trafficking, and intracellular localization of CLN3

In summary, CLN3 contains a farnesylation site at residues that are presumed to anchor the protein to intracellular or plasma membranes. However, mutagenesis of the putative farnesylation motif did not alter lysosomal localization of untagged, overexpressed CLN3. Thus, predicted farnesylation of CLN3 is not required for its lysosomal localization (Haskell et al., 2000; Pullarkat & Morris, 1997) but may have other, yet unidentified, roles.

2.7.1. Biosynthesis, trafficking, and intracellular localization of wild‐type CLN3

Due to its low expression, hydrophobic nature, and lack of suitable antibodies capable of detecting endogenous CLN3, examination of the biosynthesis, PTMs, intracellular trafficking and localization of CLN3 were performed via overexpression in COS‐1, HeLa, baby hamster kidney (BHK), and normal rat kidney epithelia (NRK) cell lines. Most of the results are based on antibodies raised against the N‐terminal domain (h345, aa4‐19) or the large second cytosolic loop of human CLN3 (h385, aa242‐258, Q438, aa251‐265) (Haskell et al., 2000; Järvelä, Lehtovirta, Tikkanen, Kyttälä, & Jalanko, 1999).

Pulse‐chase experiments in transfected COS‐1 cells indicated that CLN3 is synthesized as an N‐glycosylated single‐chain polypeptide and is localized to the lysosomal compartment (Järvelä et al., 1998). Moreover, double immunoflourescence analyses in CLN3 overexpressing HeLa cells revealed strong co‐localization of CLN3 with the lysosomal marker protein Lamp1 (Kyttälä et al., 2004). This study likewise revealed a weak co‐localization of CLN3 with markers of the ER and early endosomes (early endosomal antigen 1; EEA1), whereas no colocalization was detected with the 300 kDa mannose 6 phosphate (M6P) markers of the trans‐Golgi/late endosome network, plasma membrane or mitochondria. Colocalization of CLN3 with lysosomal marker protein Lamp‐1 was also confirmed in transiently transfected BHK cells (Järvelä et al., 1999) and in neuronal cells. In transfected primary hippocampal neurons and glia cells CLN3 co‐localized mainly with the lysosomal marker Lamp‐1 and occasionally with EEA1 (Kyttälä et al., 2004). In transfected mouse primary telencephalic neurons, the distribution of CLN3 overlapped with lysosomal markers and synaptic vesicle marker SV2 (Järvelä et al., 1999). Indeed, the vast majority of studies on CLN3 have been in relation to the lysosome or have assumed that the primary function of CLN3 is lysosomal. However, it is important to note that CLN3 is present in multiple compartments of the cell, the significance of which is unknown. For instance, CLN3 was also detected at the Golgi/trans‐Golgi network and in more peripheral transport vesicles. Some particles were also detected at the plasma membrane (Kyttälä et al., 2004).

To rule out mislocalization of CLN3 due to high overexpression, lysosomal localization of CLN3 was confirmed by double immunoflourescence microscopy in NRK cells stably expressing low levels of CLN3 in an inducible manner (Girotti & Banting, 1996; Kyttälä et al., 2004; Luiro et al., 2004; Reaves & Banting, 1994). Moreover, cryoimmunoelectron microscopy of NRK cells stably transfected with untagged CLN3 demonstrated co‐localization of CLN3 with cathepsin D and LIMPII in lysosomal structures.

Lysosomal sorting motifs of CLN3

Traditionally, M6P‐tagged lysosomal enzymes are transported to late endosomes via vesicular transport. To test whether CLN3 is transported by the same mechanism as lysosomal enzymes, investigators expressed GFP‐CLN3 in CHO cells in presence of I‐M6P. No radioactive signal was incorporated into GFP‐CLN3 suggesting that CLN3 is directed to the lysosomal membrane by an alternative mechanism (Michalewski et al., 1999). Indeed, lysosomal targeting of membrane proteins is mediated by short linear sequences located in their cytosolic domains (Braulke & Bonifacino, 2009). These include tyrosine and acidic cluster dileucine‐based lysosomal sorting motifs which fit the consensus sequences (YXXO) and (D/E)XXXL(L/I), respectively, where X can be any amino acid and O is an amino acid with a large hydrophobic side chain (Bonifacino & Traub, 2003). These sorting motifs interact with cytosolic heterotetrameric adapter proteins AP1‐5 which mediate the packaging of transmembrane cargo into vesicles (Robinson, 2015). Amino acid sequence analysis of the carboxy‐terminal region of CLN3 suggests that the C‐terminal contains one or more tyrosine‐binding motifs (370–374, 378–382, 387–391) which are linked to cytoplasmic adapter complexes involved in sorting of integral membrane proteins to lysosomes (Höning, Sandoval, & von Figura, 1998; Ohno et al., 1998). CLN3 also possess a novel dominant dileucine‐based sorting signal in the predicted second cytoplasmic loop, EEE(X)8LI, and an unconventional M(X)9G sorting motif in the C‐terminal tail (Kyttälä et al., 2004; Storch et al., 2007). These complex sorting motifs are required for the transport of CLN3 to lysosomes. Using binding assays and immunoflourescence techniques, researchers determined that the dileucine motif binds both AP‐1 and AP‐3 in vitro and both adaptor complexes are required for sequential sorting of CLN3 protein (Kyttälä et al., 2005) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lysosomal targeting motifs of CLN3

Localization of endogenous CLN3 protein

Ezaki and coworkers demonstrated by subcellular fractionation of mouse livers that endogenous CLN3 is present in lysosomal fractions positive for the lysosomal markers cathepsin B, cathepsin D, Lamp1, Lamp2, and Limp2 (Ezaki et al., 2003). No codistribution of CLN3 with the mitochondrial marker subunit IV of cytochrome oxidase or the Golgi apparatus marker G58K was found in mouse liver. Immunohistochemistry of rat liver showed partial colocalization of endogenous CLN3 with the lysosomal marker acid phosphatase and the late endosomal marker lysobisphosphatidic acid. However, CLN3 did not overlap with EEA1, the cis‐Golgi marker protein GM 130, or the ER marker protein disulfide isomerase (PDI, Ezaki et al., 2003). Lysosomal localization of endogenous CLN3 was also demonstrate in human tissue by a proteomic approach using purified membranes of placental lysosomes (Schröder, Elsässer, Schmidt, & Hasilik, 2007).

Localization of CLN3 mutant protein

More than 60 different mutations in the CLN3 gene have been identified in patients with CLN3 disease (see Table 1 and http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ncl/cln3.shtml). The most common genomic deletion (of 966 bp) results in the biosynthesis of a truncated CLN3 polypeptide composed of 153 canonical amino acids followed by 28 novel amino acids (Batten Disease Consortium, 1995). Based on experimentally determined membrane topology of the Ruonala group the mutant, truncated CLN3 protein is composed of the first two transmembrane domains and a large, C‐terminal cytosolic domain (Ratajczak et al., 2014). Based on an alternative schematic model of Nugent and coworkers the mutant, truncated CLN3 is composed of the first three transmembrane domains followed by 28 novel amino acids located on the luminal side of the membrane (Nugent et al., 2008). In both cases, mutant CLN3 lacks three or four transmembrane domains, the cytosolic loop, and the C‐terminal domain containing the lysosomal sorting motifs and the C‐terminal CQLS farnesylation site (Kyttälä et al., 2004; Storch et al., 2007).

Pulse‐chase analyses of truncated CLN3 expressed in BHK cells revealed a 24 kDa polypeptide which was not further processed in a 6 hr chase period (Järvelä et al., 1999). Double immunoflourescence analyses of truncated CLN3 expressed in BHK cells revealed major co‐localization of CLN3 with the ER marker PDI indicating its retention in the ER (Järvelä et al., 1999). In line with these findings, substitution of the entire C‐terminal domain of CLN3 with cytoplasmic tails of M6P receptors led to retention of chimeric proteins in the ER indicating the importance of the CLN3 C‐terminal for proper ER exit (Storch et al., 2007).

It has long been a matter of debate whether patients that are homozygous for the 966bp deletion in CLN3, produce a biologically active mutant protein. Studies conducted by investigators at the University College London comparing healthy, and affected patient fibroblasts in the presence of RNA interference, support the presence of mutant CLN3 transcripts and postulate the presence of CLN3 protein activity (Kitzmüller et al., 2008). In contrast, researchers at Sanford Children's Health Research Center found a substantial decrease in the transcript level of truncated CLN3 in patient fibroblasts, together with the analysis of transcripts expressed in the Cln3Dex1‐6 mouse and in silico prediction of the expected consequences of truncated protein, support the argument that nonsense‐mediated decay ensures that no functional (mutant) protein is made (Chan, Mitchison, & Pearce, 2008; Miller, Chan, & Pearce, 2013). Moreover, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital provide further evidence that support the role of nonsense‐mediated decay in the regulation of mutant CLN3 protein. However, Northern blot analyses of liver, kidney and brains of wild‐type and homozygous mutant Cln3Dex7/8 knock‐in mice revealed decreased yet stable levels of mutant RNA consistent with the presence of CLN3 mRNA in patient tissue (Cotman et al., 2002 ; "Isolation of a novel gene underlying Batten disease, CLN3. The International Batten Disease Consortium," 1995 ) . Unfortunately, due to challenges associated with the ability of current reagents (antibodies) to detect endogenous CLN3 protein, no consistent results regarding intracellular localization or quantification of the protein have been possible for either wild‐type, mutant, or variant forms of CLN3 protein.

Expression and localization studies of disease‐associated, CLN3 missense mutations suggest that reduced or complete loss of CLN3 function results in decreased protein half‐life rather than a mislocalization. These studies also indicated that in CLN3 disease, caused by missense mutations, it is the loss of protein and not mislocalization that contributes to pathogenesis. In BHK cells expressing CLN3 E295K, the mutant CLN3 protein co‐localized with Lamp‐1 indicating correct lysosomal localization (Järvelä et al., 1999). Moreover, in transiently transfected human epithelial lung carcinoma cells (A‐549) mutant CLN3 with patient‐derived missense mutations V330F, R334H, L101P, L170P, and E295K colocalized with the lysosomal marker Lamp‐1, further supporting proper lysosomal localization with these mutations (Haskell et al., 2000). Conversely, expression of CLN3 carrying nonsense and frameshift mutations led to a retention of the protein in the ER. In HeLa cells transiently expressing p. Glu399X or p. CLN3 fsG424, mutant CLN3 colocalized with the ER protein PDI in immunoflourescence analyses indicating retention in the ER (Kyttälä et al., 2004). No experimental evidence exists on the consequences of other nonsense mutations (p.Trp35X, p.Glu17X, p.Glu72X, p.Arg89X, p.Ser161X, p.Ser162X, p.Tyr199X, p.Gln211X, p.Lys262X, p.Glu395X, p.Tyr322X, p.Gln327X, p.Gln352X, p.Thr400X, p.Ser423X) or frameshift mutations (p.Thr80Asn fsX12, p.Tyr124Leu fsX36, p.Arg127Pro fsx55, p.Arg127Gly fsX54, p.Gly154Ala fs29, p.Val142Leu fsX39, p.Gly187Asp fsX48, p.Gly190Glu fsX65, p.Ala196Gly fsX40, p.Ser208Phe fsX28, p.Gly264Val fsX29, p.His315Gln fsX67, p.Leu350Cys fsX27, p.Leu379Met fsX11, p.Leu425Ser fsX87) identified in CLN3 patients. For a visual representation of disease‐causing mutations, see Figure 2. For more and continually updated information regarding disease‐causing mutations please see http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ncl/cln3.shtml.

Transient expression of the 966bp deletion, a common JNCL mutation and Q295K, a missense mutation predicted to be in the 5th transmembrane of the 6‐transmembrane model described by Nugent et al (Nugent et al., 2008) demonstrated that CLN3 protein with the common mutation is retained in the ER, whereas, Q295K mutants localize to the expected lysosomal compartment (Järvelä et al., 1999). Q295K is associated with an atypical presentation of juvenile Batten disease. Visual failure initiates and proceeds similar to children with the common deletion. However, normal MRI results have been reported for 2 decades longer than in patients with the common deletion (Järvelä et al., 1997; Wisniewski, Connell, et al., 1998).

NB: There is an error in Jarvela et al 1999 reading the amino acid code. The missense mutation is a change of glutamic acid (not glutamine) to lysine (i.e. E295K, not Q295K)

The 461–677 common deletion mutant localizes to the cell soma whereas wild‐type and Q295K co‐localize to the cell soma and neurites. The authors further report CLN3 co‐localizes with synaptic vesicle marker SV2 (antibody developed by Kathleen Buckley Harvard Medical School, Boston MA). Localization of wild‐type CLN3 protein to synaptic vesicles has not been confirmed by another laboratory. In 2001, Luiro and colleagues reported, using the same polyclonal antibody raised against amino acid residues (242–258, EEEAESAARQPLIRTEA), that CLN3 protein targets to synaptic fractions but not synaptic vesicles (Järvelä et al., 1998; Luiro, Kopra, Lehtovirta, & Jalanko, 2001). Human retinal cells transfected with CLN3 and immunostained with an antibody raised against the CLN3 peptide 242–258 showed a beads‐on‐a‐string pattern in neurites, partial co‐localization with SV2, and no co‐localization with LAMP1 (Luiro et al., 2001).

Localization of epitope‐tagged CLN3 protein

Golabek and colleagues reported results obtained from expressing full‐length CLN3 fused with GFP in COS‐1, HeLa, and human neuroblastoma (SK‐N‐SH) cell lines. Using western blotting, Percoll density gradient fractionation, and Triton X‐114 extraction, the authors demonstrated that the product of the CLN3 gene is a highly glycosylated protein found within membrane‐enriched fractions (Golabek et al., 1999). [The authors state that the results of their experiments indicate that CLN3 protein is lysosomal. However, the fractionation methods used do not separate subcellular and plasma membranes from one another, therefore making it impossible to tease out the precise localization of CLN3].

Kida and colleagues expressed full‐length and truncated CLN3 fused to GFP at its N‐terminus (GFP‐CLN3) in CHO and SK‐N‐SH cell lines (Kida et al., 1999). Using co‐immunoflourescence analyses the authors showed that full‐length GFP‐CLN3 fusion protein colocalizes with lysosomal markers Lamp‐1 and Lamp‐2 and with the late endosomal marker Rab7. GFP‐CLN3 was found in the ER, in a few vesicular structures of the Golgi apparatus, and in COPI‐coated vesicles, most likely due to the presence of newly synthesized CLN3 trafficking from the ER to the Golgi apparatus. GFP‐CLN3 did not colocalize with markers of mitochondria or plasma membrane. In contrast, truncated GFP‐CLN3 that lacked either the C‐terminal domain (GFP‐CLN3 aa 1–322 and GFP‐CLN3 aa 1–138) or the N‐terminal domain (GFP‐CLN3 aa138–438) did not codistribute with lysosomal markers thus, indicating their mislocalization. Most of the truncated fusion proteins either localized to the cytoplasm, nucleus, or ER similar to GFP alone. However, mutant CLN3, with double‐point mutations Leu425Leu426 into Gly425Gly426, at its putative dileucine motif, localized to lysosomes, in a similar fashion to wild‐type, full‐length GFP‐CLN3 (Kida et al., 1999). Studies in CHO cells stably expressing GFP‐CLN3 in the presence of the pharmacological N‐glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin suggest that N‐glycosylation is not required for correct targeting of CLN3 to lysosomes. However, treatment with Monensin, a Na+ ionophore which blocks glycoprotein secretion, produced retention of GFP‐CLN3 in vesicular structures of the Golgi apparatus in the perinuclear space, suggesting that CLN3 fusion protein is transported to the lysosomal compartments through the trans‐Golgi cisternae (Kida et al., 1999).

In contrast to the data described above, Haskell and coworkers showed a nonvesicular distribution of N‐terminal tagged GFP‐CLN3 which overlapped with the Golgi marker beta‐COP in transfected A549 cells, indicating its localization to the Golgi apparatus (Haskell, Derksen, & Davidson, 1999). Haskell et al also found no colocalization of GFP‐CLN3 with lysosomal marker Lamp‐1 or the mitochondrial marker mtHSP60. When disrupted in the presence of brefeldin A, ER‐like staining was noted. The authors postulated that, if wild‐type CLN3 protein localizes to lysosomes and mitochondria under normal conditions, their N‐terminal tag disrupts such localization.

CLN3 fused to GFP at its C terminus (CLN3‐GFP) mainly colocalized with Golgi markers as determined by immunofluorescence analysis (Kremmidiotis et al., 1999). In transiently transfected fibroblasts, HeLa and COS‐7 cells and stably transfected HeLa cells CLN3‐GFP fluorescence codistributed with wheat germ agglutinin coupled to Texas red. Stable expression of CLN3‐GFP in HeLa cells showed perinuclear, asymmetric localization with the Golgi apparatus, minor localization to the ER and lysosomes, and no apparent localization to the nucleus, mitochondria, or cell surface membrane. A juxtanuclear, asymmetric Golgi‐like localization pattern was also observed in transiently transfected HeLa, COS‐7, and fibroblast cells (Kremmidiotis et al., 1999).

2.7.2. Overexpressed, mutant CLN3 protein

More than 80% of the GFP–CLN3 fusion protein can be extracted by phase separation in a solution of Triton X‐114 indicating that CLN3 is a highly hydrophobic membrane protein (Michalewski et al., 1999).

Using immunoelectron microscopy, investigators analyzed the intracellular processing and localization of two CLN3 protein mutants, 461–677 deletion, or the “1 kb” deletion present in 85% of CLN3 alleles (73% of affected patients) and E295K [corrected], a rare missense mutation. Pulse‐chase labeling and immunoprecipitation of the 461–677 deletion and E295K mutation indicated that 461–677 deletion protein is synthesized as a ~24 kDa polypeptide, whereas the maturation of E295K mutant [corrected] resembles wild‐type CLN3 protein. Transient expression of the two mutants in BHK cells showed that 461–677 deletion protein is retained in the ER, whereas E295K [corrected] mutant was capable of reaching the lysosomal compartment. Using mouse primary neurons, investigators showed that wild‐type and E295K [corrected] mutant CLN3 proteins localize to the soma and neurites, whereas the 461–677 deletion protein is not found in neurites (Järvelä et al., 1999).

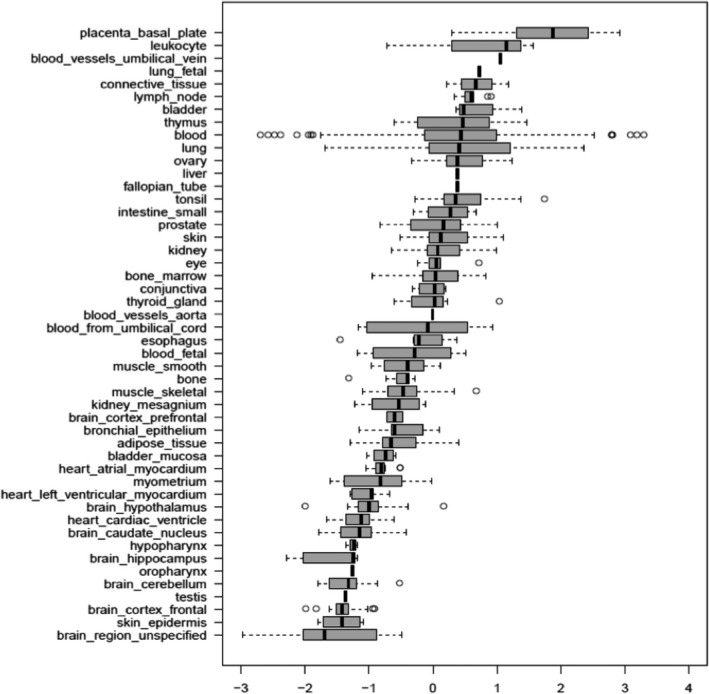

3. TISSUE DISTRIBUTION

CLN3 is universally expressed in multiple human tissues. Immunoblot, immunohistochemistry, Northern blot, and PCR analyses reveal CLN3 protein and mRNA expression in the nervous system, glandular/secretory system, skeletal muscle, gastrointestinal tract, and cancer tissues (Chattopadhyay & Pearce, 2000; Margraf et al., 1999; Persaud‐Sawin, McNamara, Rylova, Vandongen, & Boustany, 2004; Rylova et al., 2002).

In the brain, reactivity for CLN3 is present in astrocytes and neurons, and is more pronounced in the cells of the gray matter, where a larger percentage of astrocytic cells were stained. Capillary endothelium also showed cytoplasmic CLN3 expression. Overall, the expression is similar in intensity and distribution in all of the areas of brain examined, including frontal and temporal cerebral lobes, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and pons (Chattopadhyay & Pearce, 2000; Margraf et al., 1999). Peripheral nerves also express CLN3 (Margraf et al., 1999; Persaud‐Sawin et al., 2004).

In the glandular/ secretory system CLN3 is present in the pancreas (islet somatostatin‐secreting delta cells) (Boriack & Bennett, 2001; Margraf et al., 1999), kidney, testis (in the Sertoli and maturing germ cells), lungs, lymph nodes, placenta, uterus, prostate, ovary, liver, adrenal gland, thyroid, salivary gland, and mammary gland (Chattopadhyay & Pearce, 2000; Margraf et al., 1999).

In the gastrointestinal tract, CLN3 expression is found in stomach, duodenum, jejunam, ileum, ileocecum, appendix, colon and rectum (Chattopadhyay & Pearce, 2000; Rylova et al., 2002). CLN3 is also expressed in fibroblasts (Persaud‐Sawin et al., 2004), heart, and skeletal muscle (Chattopadhyay & Pearce, 2000).

In cancer tissues, CLN3 mRNA and protein are overexpressed in glioblastoma (U‐373G and T98g), neuroblastoma (IMR‐32, SH‐SY5Y, and SK‐N‐MC), prostate (Du145, PC‐3, and LNCaP), ovarian (SK‐OV‐3, SW626, and PA‐1), breast (BT‐20, BT‐549, and BT‐474), and colon (SW1116, SW480, and HCT 116) cancer cell lines, but not in pancreatic (CAPAN and As‐PC‐1) or lung (A‐549 and NCI‐H520) cancer cell lines. Indeed, CLN3 expression is 22%–330% higher in 8 of 10 solid colon tumors when compared with the corresponding normal colon tissue control (anHaack et al., 2011; Rylova et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2014).

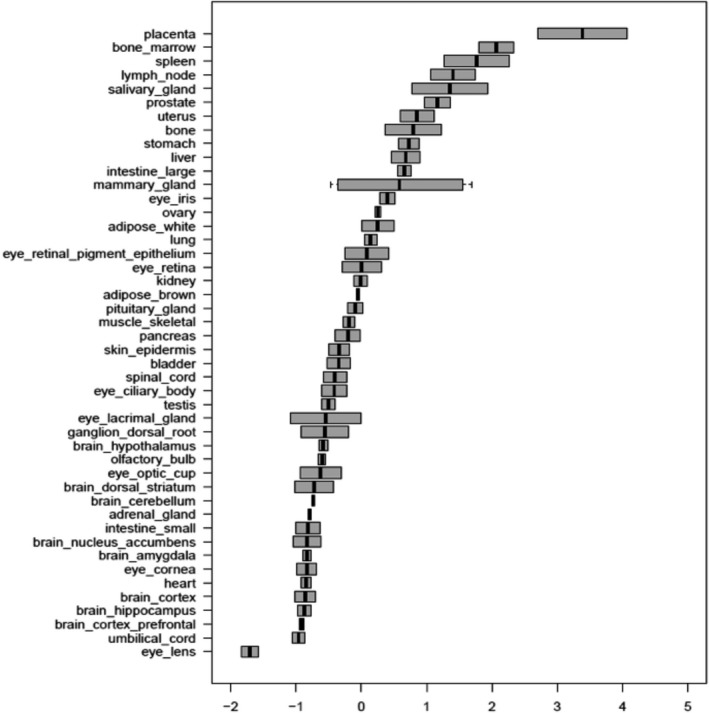

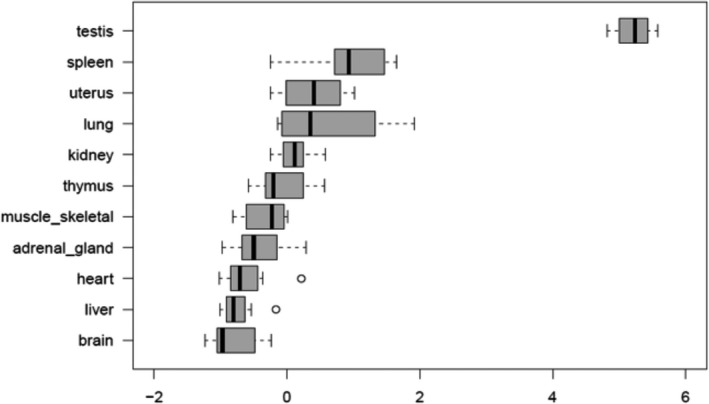

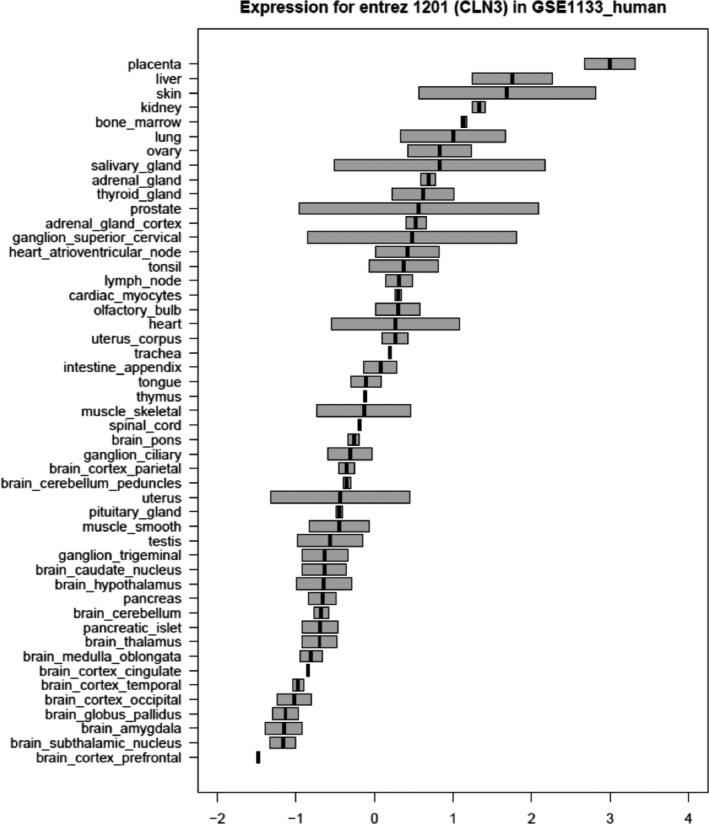

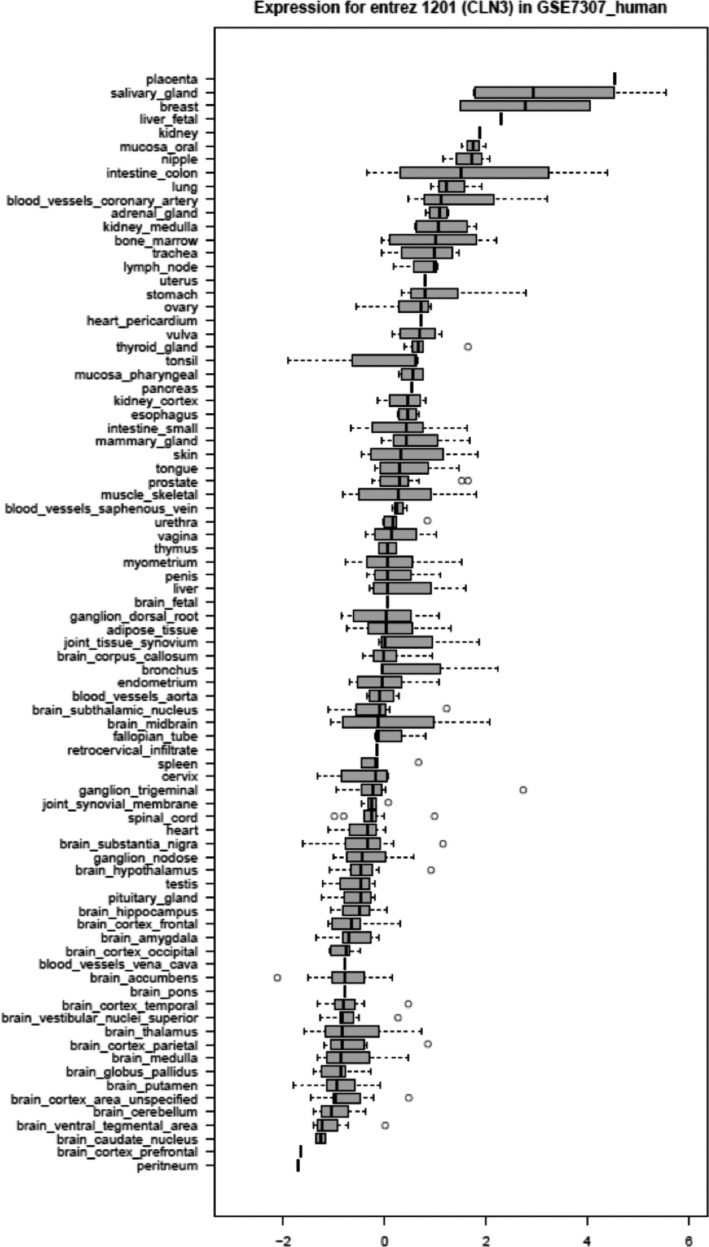

3.1. Gene expression data analysis for CLN3

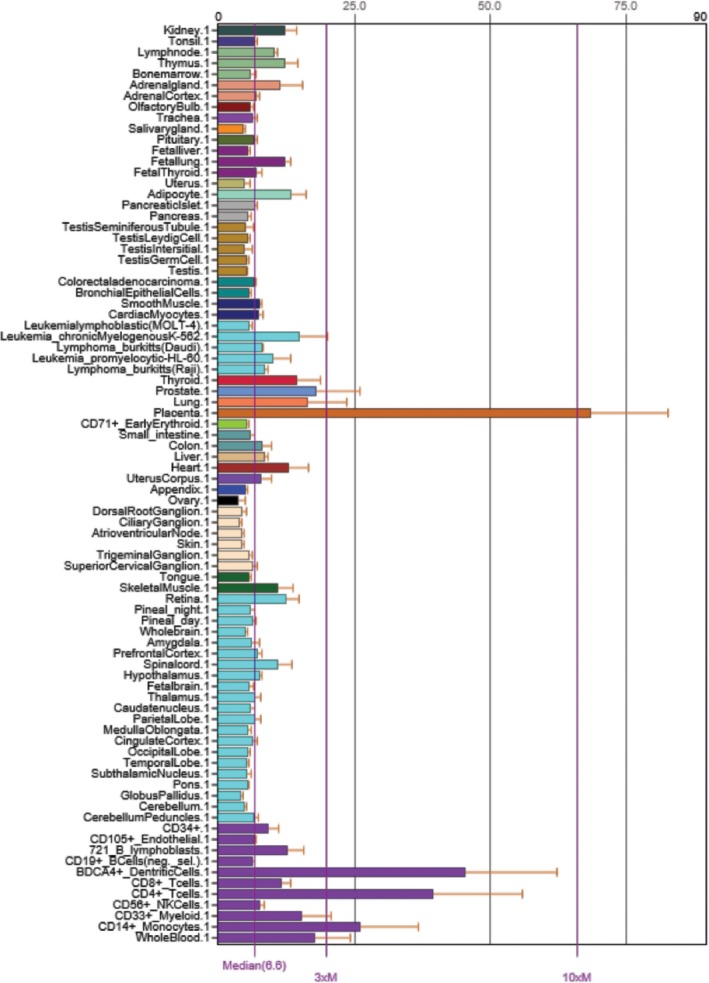

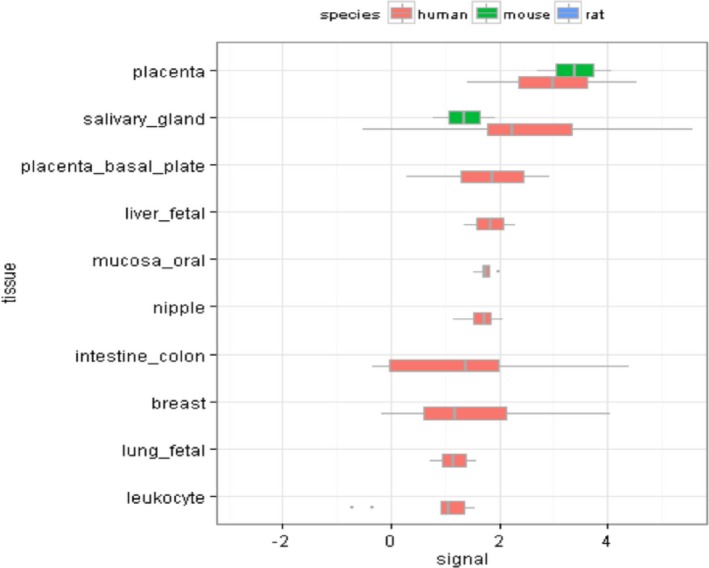

Tissue expression of CLN3 was retrieved from several sets of expression data collected across the ArrayExpress database (Rustici et al., 2013) and NCBI GEO (GSE1133, GSE2361, GSE7307, GSE30611) (Barrett et al., 2013) (Table 6).

Table 6.

NCBI GEO data sets used for tissue specific expression analysis

| Figure (below) | Dataset | Species | Platform | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 4 | E‐MTAB‐62 | Human | Affymetrix HG‐U133A | Human gene expression atlas of 5,372 samples representing 369 different cell and tissue types, disease states and cell lines. |

| Figure 5 | GSE10246 | Mouse | Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array | Multiple tissues were taken from 182 naïve male C57BL6 mice and hybridized to mouse genome arrays to profile a range of gene expressions in normal tissues. |

| Figure 6 | GSE53960 | Rat | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | As part of the SEQC consortium efforts, a comprehensive rat transcriptomic BodyMap created by performing RNA Seq on 320 samples from 11 organs of both sexes of juvenile, adolescent, adult and aged Fischer 344 rats. |