Abstract

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is defined as a group of genetically and clinically heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorders. Interplay between de novo and inherited rare variants has been suspected in the development of ASD.

Methods

Here, we applied 750K oligonucleotide microarray analysis and whole‐exome sequencing (WES) to five trios from Taiwanese families with ASD.

Results

The chromosomal microarray analysis revealed three representative known diagnostic copy number variants that contributed to the clinical presentation: the chromosome locations 2q13, 1q21.1q21.2, and 9q33.1. WES detected 22 rare variants in all trios, including four that were newly discovered, one of which is a de novo variant. Sequencing variants of JMJD1C, TCF12, BIRC6, and NHS have not been previously reported. A novel de novo variant was identified in NHS (p.I7T). Additionally, seven pathogenic variants, including SMPD1, FUT2, BCHE, MYBPC3, DUOX2, EYS, and FLG, were detected in four probands. One of the involved genes, SMPD1, had previously been reported to be mutated in patients with Parkinson's disease.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that de novo or inherited rare variants and copy number variants may be double or multiple hits of the probands that lead to ASD. WES could be useful in identifying possible causative ASD variants.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Chromosomal microarray analysis, Copy number variant, Whole‐exome sequencing

We applied 750K oligonucleotide microarray analysis and whole‐exome sequencing to five trios from Taiwanese families with ASD. A novel de novo variant was identified in NHS (c.20T>C; p.I7T). de novo or inherited rare variants and copy number variants may be double or multiple hits of the probands that lead to ASD.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which belongs to a group of neurobehavioral syndromes, is characterized by significantly impaired social interaction and communication as well as by restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behaviors, interests, and activities (Johnson, Myers, & American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With, 2007). The prevalence of ASD is estimated to be 1:59 children and 1:100 adults (Baio et al., 2018; Brugha et al., 2011). The rate of ASD is higher in males than in females (4:1), which is higher than those of Down syndrome and epilepsy. Developmental delays are observed in approximately 40% of individuals with ASD, and approximately 70% show some level of intellectual disability. ASD has strong genetic contributions, and single‐gene disorders are recognized as causative in less than 20% of ASD cases (Herman et al., 2007). The most consistently reported single gene disorders associated with ASD are fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis. The prevalence of fragile X syndrome among subjects with ASD is 1.5%–3% (Clifford et al., 2007). The genetic etiology of ASD is complex.

Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) examines gross chromosomal structural abnormalities and can detect deletions and duplications as well as the size and presence of known genes within a chromosomal region. The most common microarray abnormalities in ASD involve the chromosome regions 15q11‐q13, 16p11.2, and 22q11.2 (Carter & Scherer, 2013; Roberts, Hovanes, Dasouki, Manzardo, & Butler, 2014). In the clinical setting, CMA, which has a diagnostic yield ranging from 7.0% to 9.0%, is recommended as the first tier test for children and adults presenting with ASD (Battaglia et al., 2013; McGrew, Peters, Crittendon, & Veenstra‐Vanderweele, 2012; Shen et al., 2010).

Technological improvements have led to tremendous advances in our understanding of the genetic basis of ASD over the past 10 years. Most genomic studies on ASD using next‐generation sequencing (NGS) have focused on protein‐coding regions and analyzed trio information to identify sequence‐level de novo mutations (De Rubeis et al., 2014; Iossifov et al., 2014, 2012; Neale et al., 2012; O'Roak et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2012). Hundreds of genes have been implicated in the cause of ASD. The identification of new genes involved in ASD has made this condition a strong candidate for genome‐based diagnostic testing, which consists of CMA and NGS, as well as whole‐genome sequencing (WGS) and whole‐exome sequencing (WES).

Recently, Guo et al. applied WGS, WES, and CMA to investigate genomic variants in ASD families and compared the performances of WGS and WES for use in diagnostic testing (Guo et al., 2019). The authors reported the diagnostic utility of WGS for detecting disorder‐related variants (particularly multiple rare‐risk variants that contribute to phenotypic severity in individuals with ASD), identifying genetic heterogeneity in multiplex ASD families and predicting novel ASD‐associated genes for future study.

In this study, we aimed to define causative or susceptibility variants for ASD and their copy number variants by CMA. We studied five subjects who are typical of those seen in developmental pediatric clinics. The sample was stratified based on the clinical phenotype of the patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects with ASD

Five patients with a clinical diagnosis of ASD were enrolled in the study. Autism screening was performed using the Autism Behavior Checklist, Taiwanese version (ABC‐T), which was modified from the third edition of the Autism Behavior Checklist of Autism Screening Instrument for Education Planning (Krug, Arick, & Almond, 1980). Family members were also enrolled for inheritance pattern analysis. Blood samples were obtained, and genomic DNA was extracted using the Nucleospin® Blood Kit (Macherey‐Nagel, GmbH & Co. KG, Duren, Germany). This study was approved by the China Medical University Hospital (CMUH105‐REC1‐039).

2.2. Single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array analysis

DNA samples (250 ng) were hybridized to the Affymetrix CytoScan 750K array according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 750K array contained greater than 750,000 markers for copy number analysis and 200,000 SNP probes for genotyping. The following standard experimental procedures were performed: digestion, ligation, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), PCR purification, fragmentation, labeling, hybridization, washing, staining, and scanning. After hybridization, GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G, Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console software, and Affymetrix ChAS 2.0 software were used for scanning the arrays, extracting the images, and performing the analysis, respectively. All data had to pass quality control (QC) metrics including the median of the absolute values of all pairwise differences ≤ 0.30, SNPQC ≥ 15, and a waviness standard deviation ≤ 0.12.

2.3. WES

In total, 100 ng of genomic DNA based on Qubit quantification was mechanically fragmented on a M220 focused ultrasonicator Covaris (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA), and QC was performed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to ensure an average fragment size of 150–200 bp. End repair, A‐tailing, adaptor ligation, and enrichment of DNA fragments were then performed. A 200–400 bp band was gel‐selected, and exome capture was performed using a TruSeq Exome Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The DNA library was quantified in the Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and Agilent 4200 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Samples were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 platform and 150‐bp paired‐end reads were generated.

2.4. Data analysis

Base calling and quality scoring were performed by an updated implementation of real‐time analysis on the NextSeq500 system. Bcl2fastq Conversion Software was used to demultiplex data and convert the BCL files to FASTQ files. Sequenced reads were trimmed for low‐quality sequences and mapped to the human reference genome (hg19) using the Burrows–Wheeler alignment (Li & Durbin, 2009). Finally, SNPs and small insertions/deletions were detected using Genome Analysis Toolkit and VarScan using their default settings (Koboldt et al., 2012; McKenna et al., 2010). ANNOVAR was used to annotate the VCF files by gene, region, and filters from several other databases (Wang, Li, & Hakonarson, 2010). Finally, we annotated the mutations using several databases and tools, including dbSNP (build 147), GnomAD (http://gnomad-old.broadinstitute.org/), Denovo‐db (http://denovo-db.gs.washington.edu/denovo-db/), ClinVar, Polyphen‐2, SIFT, and CADD (Adzhubei et al., 2010; Kircher et al., 2014; Kumar, Henikoff, & Ng, 2009; Landrum et al., 2014; Sherry et al., 2001; Turner et al., 2017). Pathways were analyzed using STRING (https://string-db.org). Additionally, ASD‐related genes reported in the public databases OMIM and AutDB were selected (Basu, Kollu, & Banerjee‐Basu, 2009).

2.5. Variant validations and segregation analysis

We used PCR and Sanger sequencing to validate candidate variants from WES. Segregation analysis was carried out on family members. PCR primers were designed using Primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). Table S1 lists the designed primers. The products were directly sequenced with an ABI PRISM BigDye kit using an ABI 3130 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing results were analyzed using the software Chromas, version 2.23.

3. RESULTS

Following QC of the WES data, five probands were analyzed further and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. For these, a mean coverage depth of 141X was achieved (Table 1). Patient 1, a 21‐year‐old male who presented with autism combined with epilepsy, had an ABC‐T score of 28 (Table 3). The 750K microarray showed a 2q13 duplication (482.154 kbp) containing three OMIM genes (RGPD6, MALL, and NPHP1). WES revealed four rare variants in SHANK3 (c.3658A > G; p.T1220A; rs751183635), DNAH10 (c.2800C > T; p.R934C; rs757691040), ESR2 (c.1228C > T; p.R410C; rs528840784), and NAALADL2 (c.1424G > A; p.R475H; rs372908344) (Table 2). Among them, SHANK3 and ESR2 are involved in negative regulation of signal transduction (GO:0,009,968). Furthermore, three pathogenic mutations were observed, SMPD1 (p.P186L), FUT2 (p.R202X), and BCHE (p.T343fs).

Table 1.

Whole‐exome sequencing alignment and mean base depth statistics for 5 probands for the analysis

| Case | Total raw reads | Total effective reads | Reads mapped to genome | Average read depth of target regions | Number of SNVs on target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD23 | 172,869,310 | 159,621,404 | 159,588,187 | 139.246 | 34,233 |

| ASD24 | 186,622,966 | 172,125,108 | 172,094,954 | 143.877 | 34,284 |

| ASD25 | 192,186,388 | 173,661,734 | 173,616,740 | 126.054 | 34,093 |

| ASD26 | 191,244,742 | 176,442,474 | 176,407,661 | 154.055 | 34,942 |

| ASD27 | 167,228,010 | 153,870,614 | 153,839,987 | 141.935 | 33,945 |

| Average | 182,030,283 | 167,144,267 | 167,109,506 | 141.033 | 34,299 |

Table 3.

Summary of the phenotypic features of patients with autism spectrum disorder and the relevant findings of the study

| Patient | Rare variants in autism‐related genes involved pathwaysa | ABCT (47 items) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative regulation of Wnt signaling pathway (GO:0030178) |

Negative regulation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway (GO:0090090) |

Negative regulation of signal transduction (GO:0009968) |

Endoplasmic reticulum calcium ion homeostasis (GO:0032469) |

Sensory (8 items) |

Relating (11 items) | Body and object use (12 items) | Language (8 items) | Social and self‐help (8 items) |

Total score |

|

| ASD23 | + | 3 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 28 | |||

| ASD24 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 27 | ||||

| ASD25 | + | + | + | + | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 20 |

| ASD26 | + | + | + | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 27 | |

| ASD27 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 36 | ||||

Rare variants in autism‐related genes (as shown in Table 2) are involved in several pathways.

Table 2.

Summary of the rare variants in autism‐related genes detected in this study

| Proband ID (Gender) | Mode of Inheritance | Identified Variant | Genotype | Functional prediction | MAF | Abnormal chromosomal microarray data | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Base Change | Amino Acid Change | Proband | UF | UM |

PolyPhen2 |

SIFT | CADD | ExAC/1000 Genome project/GnomAD/Denovo‐db | Del/Dup | Chromosome location | Chromosome coordinates | Number of genes in deletion or duplication | |||

| ASD23 (M) | AD | SHANK3 | c.3658A > G | p.T1220A | A/G | A/G | A/A | NA | NA | NA | 0 | Dup | 2q13 | 110,498,141–110,980,251 | 3 | |

| AD | DNAH10 | c.2800C > T | p.R934C | C/T | C/T | C/C | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 34 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| AD | ESR2 | c.1228C > T | p.R410C | C/T | C/C | C/T | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 23.3 | 0.0006 | ||||||

| AD | NAALADL2 | c.1424G > A | p.R475H | G/A | G/A | G/G | Possibly damaging | Deleterious | 23.1 | 0.0008 | ||||||

| ASD24 (M) | AD | DLGAP3 | c.1759G > C | p.G587R | G/C | G/C | G/G | Possibly damaging | Deleterious | 27 | 0.0004 | Not detected | ||||

| AD | SLC1A2 | c.1091G > A | p.R364H | G/A | G/A | G/G | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 35 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| AD | CLTCL1 | c.1061G > A | p.R354H | G/A | G/A | G/G | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 24.9 | 0.0009 | ||||||

| ASD25 (M) | AD | WFS1 | c.2144G > T | p.S715I | G/T | G/G | G/T | Possibly damaging | Deleterious | 25 | 0.0002 | Dup | 1q21.1q21.2 | 145,895,746–147,844,777 | 10 | |

| AD | TNN | c.1681T > C | p.Y561H | T/C | T/T | T/C | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 25.7 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| AD | JMJD1C | ac.6344A > C | p.F2115C | A/C | A/C | A/A | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 29.9 | |||||||

| AD | APP | c.1748A > G | p.E583G | A/G | A/A | A/G | Possibly damaging | Deleterious | 28.8 | 0.0001 | ||||||

| AD | SYNE1 | c.9878C > T | p.S3293F | C/T | C/T | C/C | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 32 | 0.0005 | ||||||

| AD | MPP6 | c.61G > A | p.D21N | G/A | G/G | G/A | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 33 | 0.0003 | ||||||

| AD | MCC | c.60_61insAGC | p.G21delinsSG | Het | WT | Het | NA | NA | NA | 0 | ||||||

| ASD26 (M) | AD | TSC2 | c.5418T > G | p.F1806L | T/G | T/G | T/T | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 23.2 | 0.0001 | Not detected | ||||

| AD | SETBP1 | c.2842C > T | p.R948C | C/T | C/T | C/C | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 24.5 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| AD | TCF12 | ac.770C > T | p.R257H | C/T | C/C | C/T | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 28.1 | |||||||

| AD | LZTS2 | c.1259G > A | p.R420Q | G/A | G/A | G/G | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 28.6 | 0.0003 | ||||||

| AD | BIRC6 | ac.6600G > T | p.Q2200H | G/T | G/T | G/G | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 26.7 | |||||||

| AD | EPHA6 | c.527A > C | p.N176T | A/C | A/C | A/A | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 24.9 | 0.00003 | ||||||

| X‐Y pseudoautosomal | ASMT | c.451G > A | p.G151S | G/A | G/A | G/G | NA | NA | NA | 0.0005 | ||||||

| ASD27 (M) | De novo | NHS | ac.20T > C | p.I7T | C/C | T/T | T/C | Probably damaging | Deleterious | 23.9 | Dup | 9q33.1 | 118,921,750–120,012,115 | 3 | ||

Abbreviations: UF, unaffected father; UM, unaffected mother.

Variants were not reported.

Patient 2, an 8‐year‐old male, had an ABC‐T score of 27 (Table 3). The 750K microarray revealed no abnormalities. WES revealed three rare variants in DLGAP3 (c.1759G > C; p.G587R; rs762072609), SLC1A2 (c.1091G > A; p.R364H; rs147645566), and CLTCL1 (c.1061G > A; p.R354H; rs201506683) (Table 2). Additionally, two pathogenic mutations were observed, MYBPC3 (p.E334K) and DUOX2 (p.K530X).

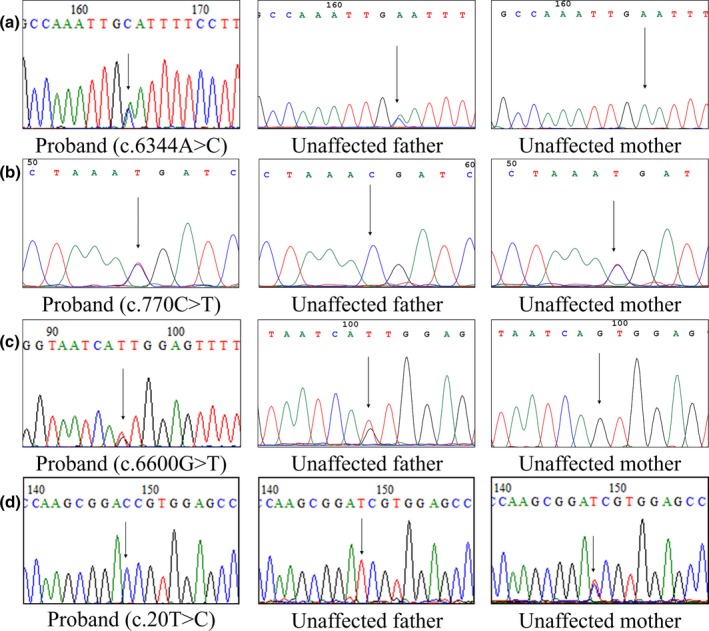

Patient 3, a 15‐year‐old male, had an ABC‐T score of 20 (Table 3). The 750K microarray showed a 1q21.1q21.2 duplication (1949.031 kbp) containing 10 OMIM genes (HYDIN2, PRKAB2, FMO5, CHD1L, BCL9, ACP6, GJA5, GJA8, GPR89B, and NBPF11). WES revealed seven rare variants in WFS1 (c.2144G > T; p.S715I; rs772022154), TNN (c.1681T > C; p.Y561H; rs777370361), JMJD1C (c.6344T > G; p.F2115C; novel) (Figure 1a), APP (c.1748A > G; p.E583G; rs778495527), SYNE1 (c.9878C > T; p.S3293F; rs770774159), MPP6 (c.61G > A; p.D21N; rs771283348), and MCC (c.60_61insAGC; p.G21delinsSG; rs72442525) (Table 2). WFS1, TNN, APP, and MCC are involved in the negative regulation of Wnt and canonical Wnt signaling pathways (GO:0030178 and GO:0090090), negative regulation of signaling transduction (GO:0009968) and endoplasmic reticulum calcium ion homeostasis (GO:0032469). Moreover, a pathogenic mutation in the EYS gene (p.C2139Y) was observed.

Figure 1.

Chromatograms of the heterozygous missense variants in JMJD1C (a), TCF12 (b), BIRC6 (c), and de novo variant in NHS (d)

Patient 4, a 6‐year‐old male, had an ABC‐T score of 27 (Table 3). The 750K microarray revealed no abnormalities. WES revealed seven rare variants in TSC2 (c.5418T > G; p.F1806L; rs200004126), SETBP1 (c.2842C > T; p.R948C; rs751366974), TCF12 (c.770G > A; p.R257H; novel) (Figure 1b), LZTS2 (c.1259G > A; p.R420Q; rs759282265), BIRC6 (c.6600G > T; p.Q2200H; novel) (Figure 1c), EPHA6 (c.527A > C; p.N176T), and ASMT (c.451G > A; p.G151S; rs192710293) (Table 2). TSC2, LZTS2 and BIRC6 are involved in the negative regulation of Wnt and canonical Wnt signaling pathways (GO:0030178 and GO:0090090) and negative regulation of signaling transduction (GO:0009968). No pathogenic mutations were detected.

Patient 5, a 10‐year‐old male, had an ABC‐T score of 36 (Table 3). The 750K microarray showed a 9q33.1 duplication (1090.359 kbp) containing three OMIM genes (PAPPA, ASTN2, and TRIM32). WES revealed one de novo variant in the NHS (c.20T > C; p.I7T) gene (Table 2 and Figure 1d). NHS p.I7T has not been previously reported. Additionally, a pathogenic mutation in the FLG gene (p.E2422X) was observed.

The mutations in our five patients were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing of DNA from both parents to determine the origins of mutation or to reveal de novo mutations.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, WES was performed to identify possible ASD causal variants in five Taiwanese families; one novel de novo variant in one trio and rare variants in each trio were successfully identified. These genes are involved mainly in the negative regulation of Wnt and canonical Wnt signaling pathways, negative regulation of signaling transduction and endoplasmic reticulum calcium ion homeostasis. We detected no association of the ABC‐T score with a particular pathway. However, possible causal variants may be missed if located within a noncoding region; thus, WGS will be necessary in future studies.

Three ASD patients (ASD25, ASD26, and ASD27) were found to carry a novel missense variant of four genes (JMJD1C, TCF12, BIRC6, and NHS) (Table 2). JMJD1C encodes a putative histone demethylase and is involved in the epigenetic control of gene transcription. This study identified a variant of JMJD1C, c.6344T > G, which results in the substitution of phenylalanine by cysteine (p.F2115C). The p.F2115C mutation is in the JmjC domain, a domain family that is part of the cupin metalloenzyme superfamily. Mutations in this gene are associated with Rett syndrome and intellectual disability (Saez et al., 2016). TCF12 encodes a member of the basic helix‐loop‐helix E‐protein family that recognizes the consensus‐binding site (E‐box) CANNTG. This study identified a variant, c.770G > A, which results in substitution of an arginine by histidine (p.R257H) in TCF12. BIRC6 encodes an inhibitor of apoptosis protein with baculoviral inhibition of apoptosis protein repeat (BIR) and ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme E2, catalytic (UBCc) domains. This study found a variant of BIRC6, c.6600G > T, which results in substitution of a glutamine by histidine (p.Q2200H). NHS encodes a protein with four conserved nuclear localization signals that function in brain development. This study identified a variant, c.20T > C, which results in substitution of isoleucine by threonine (p.I7T) in NHS. Mutations in this gene are associated with Nance–Horan syndrome (Shoshany et al., 2017). These variants were not found among the 277,264 alleles in the GnomAD database and were predicted to be damaging in silico by SIFT and to be likely damaging by Polyphen2.

Most of the variants identified in this study were found in autosomal genes, whereas one was identified in the X‐Y pseudoautosomal gene, ASMT, which has been reported to be associated with the autism phenotype and sleep disturbance (Cai et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013). In the present study, we identified one reported missense variant, pG151S, in the Taiwanese population with ASD. Additionally, we detected no obvious dominant or recessive compound heterozygous mutations in ASD‐related genes.

By considering pathogenic mutations with ClinVar, we found variants in four of five probands (80%). The pathogenic mutations were detected in SMPD1, FUT2, BCHE, MYBPC3, DUOX2, EYS, and FLG2 in four different patients (Table 4). SMPD1 encodes a lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase that converts sphingomyelin to ceramide. Defects in this gene are a cause of Parkinson's disease (Mao et al., 2017). FUT2 encodes a Golgi stack membrane protein and is highly associated with the development of inflammatory bowel disease (Wu et al., 2017). BCHE encodes a cholinesterase enzyme and is a member of the type‐B carboxylesterase/lipase family of proteins. Some of the genetic variants are prone to the development of prolonged apnea following administration of the muscle relaxant succinylcholine (Panhuizen, Snoeck, Levano, & Girard, 2010). BCHE p.T343fs has been reported in colon adenocarcinomas and esophageal carcinomas. MYBPC3 encodes the cardiac isoform of myosin‐binding protein C. Mutations in MYBPC3 are one cause of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Aurensanz Clemente et al., 2017). MYBPC3 is one of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics genes. DUOX2 encodes a glycoprotein and a member of the NADPH oxidase family. DUOX2 mutations are the most powerful genetic predisposing factors for thyroid dyshormonogenesis (Chen et al., 2018). EYS is mutated in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (Mucciolo et al., 2018). FLG2 encodes an intermediate filament‐associated protein that functions in aggregation and the collapse of keratin intermediate filaments in mammalian epidermis. Mutations in this gene are associated with ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis (Hassani et al., 2018).

Table 4.

Summary of the pathogenic mutations detected in this studya

| Proband ID | Gene | Base Change | Amino Acid Change | OMIM | Gene function | Biological process (s) | Human disease | Reported link to other neurological disorders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD−23 | SMPD1 | c.557C > T | p.P186L | 607608 | Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1 | Nervous system development | Niemann‐Pick disease, type A and B | Parkinson's disease |

| FUT2 | c.604C > T | p.R202X | 182100 | Fucosyltransferase 2 | Protein glycosylation |

Vitamin B12 plasma level Crohn disease |

Deficiency in vitamin B12, clinically associated with neurodegenerative disorders | |

| BCHE | c.1027dupA | p.T343fs | 177400 | Butyrylcholinesterase | Choline metabolic process, Neuroblast differentiation |

Butyrylcholinesterase deficiency Apnea, postanesthetic, susceptibility to, due to BCHE deficiency |

No | |

| ASD−24 | MYBPC3 | c.1000G > A | p.E334K | 600958 | Myosin binding protein C, cardiac | Cardiac muscle contraction, Ventricular cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis | Cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic | No |

| DUOX2 | c.1588A > T | p.K530X | 606759 | Dual oxidase 2 | Thyroid gland development, Thyroid hormone generation | Thyroid dyshormonogenesis | No | |

| ASD−25 | EYS | c.6416G > A | p.C2139Y | 612424 | Required to maintain the integrity of photoreceptor cells. | Detection of light stimulus involved in visual perception, Skeletal muscle tissue regeneration | Retinitis pigmentosa | No |

| ASD−26 | ||||||||

| ASD−27 | FLG | c.7264G > T | c.E2422X | 135940 | Aggregates keratin intermediate filaments and promotes disulfide‐bond formation among the intermediate filaments during terminal differentiation of mammalian epidermis. | Cornification, Establishment of skin barrier, Keratinocyte differentiation, Multicellular organism development, Peptide cross‐linking | Ichthyosis vulgaris | No |

Pathogenic mutations, according to the ClinVar database.

In conclusion, we report on five ASD patients with rare variants and one patient with a de novo variant. However, this association study was performed with only a small number of cases; therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by China Medical University Hospital (DMR‐105‐124 and CRS‐106‐028).

Chang Y‐S, Lin C‐Y, Huang H‐Y, Chang J‐G, Kuo H‐T. Chromosomal microarray and whole‐exome sequence analysis in Taiwanese patients with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7:e996 10.1002/mgg3.996

Contributor Information

Jan‐Gowth Chang, Email: d6781@mail.cmuh.org.tw.

Haung‐Tsung Kuo, Email: d6582@mail.cmuh.org.tw.

REFERENCES

- Adzhubei, I. A. , Schmidt, S. , Peshkin, L. , Ramensky, V. E. , Gerasimova, A. , Bork, P. , … Sunyaev, S. R. (2010). A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature Methods, 7(4), 248–249. 10.1038/nmeth0410-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurensanz Clemente, E. , Ayerza Casas, A. , García Lasheras, C. , Ramos Fuentes, F. , Bueno Martínez, I. , Pelegrín Díaz, J. , … Montserrat Iglesias, L. (2017). Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with a new mutation in gene MYBPC3. Clinical Case Reports, 5(3), 232–237. 10.1002/ccr3.832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio, J. , Wiggins, L. , Christensen, D. L. , Maenner, M. J. , Daniels, J. , Warren, Z. , … Dowling, N. F. (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years ‐ Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 67(6), 1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S. N. , Kollu, R. , & Banerjee‐Basu, S. (2009). AutDB: A gene reference resource for autism research. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(suppl_1), D832–D836. 10.1093/nar/gkn835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, A. , Doccini, V. , Bernardini, L. , Novelli, A. , Loddo, S. , Capalbo, A. , … Carey, J. C. (2013). Confirmation of chromosomal microarray as a first‐tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental delay, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders and dysmorphic features. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 17(6), 589–599. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugha, T. S. , McManus, S. , Bankart, J. , Scott, F. , Purdon, S. , Smith, J. , … Meltzer, H. (2011). Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(5), 459–465. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G. , Edelmann, L. , Goldsmith, J. E. , Cohen, N. , Nakamine, A. , Reichert, J. G. , … Buxbaum, J. D. (2008). Multiplex ligation‐dependent probe amplification for genetic screening in autism spectrum disorders: Efficient identification of known microduplications and identification of a novel microduplication in ASMT. BMC Medical Genomics, 1, 50 10.1186/1755-8794-1-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M. T. , & Scherer, S. W. (2013). Autism spectrum disorder in the genetics clinic: A review. Clinical Genetics, 83(5), 399–407. 10.1111/cge.12101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Kong, X. , Zhu, J. , Zhang, T. , Li, Y. , Ding, G. , & Wang, H. (2018). Mutational spectrum analysis of seven genes associated with thyroid dyshormonogenesis. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2018, 8986475 10.1155/2018/8986475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, S. , Dissanayake, C. , Bui, Q. M. , Huggins, R. , Taylor, A. K. , & Loesch, D. Z. (2007). Autism spectrum phenotype in males and females with fragile X full mutation and premutation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(4), 738–747. 10.1007/s10803-006-0205-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rubeis, S. , He, X. , Goldberg, A. P. , Poultney, C. S. , Samocha, K. , Ercument Cicek, A. , … Buxbaum, J. D. (2014). Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature, 515(7526), 209–215. 10.1038/nature13772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H. , Duyzend, M. H. , Coe, B. P. , Baker, C. , Hoekzema, K. , Gerdts, J. , … Eichler, E. E. (2019). Genome sequencing identifies multiple deleterious variants in autism patients with more severe phenotypes. Genetics in Medicine, 21(7), 1611–1620. 10.1038/s41436-018-0380-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, B. , Isaian, A. , Shariat, M. , Mollanoori, H. , Sotoudeh, S. , Babaei, V. , … Teimourian, S. (2018). Filaggrin gene polymorphisms in Iranian ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis patients. International Journal of Dermatology, 57(12), 1485–1491. 10.1111/ijd.14213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, G. E. , Henninger, N. , Ratliff‐Schaub, K. , Pastore, M. , Fitzgerald, S. , & McBride, K. L. (2007). Genetic testing in autism: How much is enough? Genetics in Medicine, 9(5), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1097GIM.0b013e31804d683b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov, I. , O’Roak, B. J. , Sanders, S. J. , Ronemus, M. , Krumm, N. , Levy, D. , … Wigler, M. (2014). The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature, 515(7526), 216–221. 10.1038/nature13908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov, I. , Ronemus, M. , Levy, D. , Wang, Z. , Hakker, I. , Rosenbaum, J. , … Wigler, M. (2012). De novo gene disruptions in children on the autistic spectrum. Neuron, 74(2), 285–299. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. P. , Myers, S. M. ; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities (2007). Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120(5), 1183–1215. 10.1542/peds.2007-2361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, M. , Witten, D. M. , Jain, P. , O'Roak, B. J. , Cooper, G. M. , & Shendure, J. (2014). A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nature Genetics, 46(3), 310–315. 10.1038/ng.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt, D. C. , Zhang, Q. , Larson, D. E. , Shen, D. , McLellan, M. D. , Lin, L. , … Wilson, R. K. (2012). VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Research, 22(3), 568–576. 10.1101/gr.129684.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug, D. A. , Arick, J. , & Almond, P. (1980). Behavior checklist for identifying severely handicapped individuals with high levels of autistic behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 21(3), 221–229. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7430288. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1980.tb01797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. , Henikoff, S. , & Ng, P. C. (2009). Predicting the effects of coding non‐synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nature Protocols, 4(7), 1073–1081. 10.1038/nprot.2009.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum, M. J. , Lee, J. M. , Riley, G. R. , Jang, W. , Rubinstein, W. S. , Church, D. M. , & Maglott, D. R. (2014). ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(Database, issue), D980–D985. 10.1093/nar/gkt1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , & Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows‐Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 25(14), 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C.‐Y. , Yang, J. , Wang, H. , Zhang, S.‐Y. , Yang, Z.‐H. , Luo, H.‐Y. , … Xu, Y.‐M. (2017). SMPD1 variants in Chinese Han patients with sporadic Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 34, 59–61. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew, S. G. , Peters, B. R. , Crittendon, J. A. , & Veenstra‐Vanderweele, J. (2012). Diagnostic yield of chromosomal microarray analysis in an autism primary care practice: Which guidelines to implement? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(8), 1582–1591. 10.1007/s10803-011-1398-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, A. , Hanna, M. , Banks, E. , Sivachenko, A. , Cibulskis, K. , Kernytsky, A. , … DePristo, M. A. (2010). The genome analysis toolkit: a mapreduce framework for analyzing next‐generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research, 20(9), 1297–1303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucciolo, D. P. , Sodi, A. , Passerini, I. , Murro, V. , Cipollini, F. , Borg, I. , … Rizzo, S. (2018). Fundus phenotype in retinitis pigmentosa associated with EYS mutations. Ophthalmic Genetics, 39(5), 589–602. 10.1080/13816810.2018.1509351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale, B. M. , Kou, Y. , Liu, L. I. , Ma’ayan, A. , Samocha, K. E. , Sabo, A. , … Daly, M. J. (2012). Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature, 485(7397), 242–245. 10.1038/nature11011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak, B. J. , Vives, L. , Girirajan, S. , Karakoc, E. , Krumm, N. , Coe, B. P. , … Eichler, E. E. (2012). Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature, 485(7397), 246–250. 10.1038/nature10989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panhuizen, I. F. , Snoeck, M. M. , Levano, S. , & Girard, T. (2010). Prolonged neuromuscular blockade following succinylcholine administration to a patient with a reduced butyrylcholinesterase activity. Case Reports in Medicine, 2010, 472389 10.1155/2010/472389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J. L. , Hovanes, K. , Dasouki, M. , Manzardo, A. M. , & Butler, M. G. (2014). Chromosomal microarray analysis of consecutive individuals with autism spectrum disorders or learning disability presenting for genetic services. Gene, 535(1), 70–78. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáez, M. A. , Fernández‐Rodríguez, J. , Moutinho, C. , Sanchez‐Mut, J. V. , Gomez, A. , Vidal, E. , … Esteller, M. (2016). Mutations in JMJD1C are involved in Rett syndrome and intellectual disability. Genetics in Medicine, 18(4), 378–385. 10.1038/gim.2015.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, S. J. , Murtha, M. T. , Gupta, A. R. , Murdoch, J. D. , Raubeson, M. J. , Willsey, A. J. , … State, M. W. (2012). De novo mutations revealed by whole‐exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature, 485(7397), 237–241. 10.1038/nature10945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. , Dies, K. A. , Holm, I. A. , Bridgemohan, C. , Sobeih, M. M. , & Caronna, E. B. ,. … Autism Consortium Clinical Genetics, DNA DC (2010). Clinical genetic testing for patients with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 125(4), e727–735. 10.1542/peds.2009-1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, S. T. , Ward, M. H. , Kholodov, M. , Baker, J. , Phan, L. , Smigielski, E. M. , & Sirotkin, K. (2001). dbSNP: The NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Research, 29(1), 308–311. 10.1093/nar/29.1.308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshany, N. , Avni, I. , Morad, Y. , Weiner, C. , Einan‐Lifshitz, A. , & Pras, E. (2017). NHS Gene Mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish Families with Nance‐Horan Syndrome. Current Eye Research, 42(9), 1240–1244. 10.1080/02713683.2017.1304560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, T. N. , Yi, Q. , Krumm, N. , Huddleston, J. , Hoekzema, K. , F. Stessman, H. A., … Eichler, E. E. (2017). denovo‐db: A compendium of human de novo variants. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D804–D811. 10.1093/nar/gkw865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. , Li, M. , & Hakonarson, H. (2010). ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high‐throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research, 38(16), e164 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Li, J. , Ruan, Y. , Lu, T. , Liu, C. , Jia, M. , … Zhang, D. (2013). Sequencing ASMT identifies rare mutations in Chinese Han patients with autism. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e53727 10.1371/journal.pone.0053727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. , Sun, L. , Lin, D. P. , Shao, X. X. , Xia, S. L. , & Lv, M. (2017). Association of fucosyltransferase 2 gene polymorphisms with inflammatory bowel disease in patients from Southeast China. Gastroenterology Research and Practice, 2017, 4148651 10.1155/2017/4148651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials