Significance

Synthesis of abscisic acid (ABA) and proteins required for its downstream signaling are ancient and found in aquatic algae, but these primitive plants do not respond to ABA and lack ABA receptors. The present work traces the evolution of ABA as an allosteric regulatory switch. We found that ancient PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE 1’s homolog proteins have constitutive ABA-independent phosphatase-binding activity that, in land plants, has gradually evolved into an ABA-activated receptor. We propose that ABA-mediated fine-tuning of the preexisting signaling cascade was a key evolutionary novelty that aided these plants in their conquest of land.

Keywords: PYL, receptor basal activity, Zygnema, abscisic acid, streptophyte algae

Abstract

Land plants are considered monophyletic, descending from a single successful colonization of land by an aquatic algal ancestor. The ability to survive dehydration to the point of desiccation is a key adaptive trait enabling terrestrialization. In extant land plants, desiccation tolerance depends on the action of the hormone abscisic acid (ABA) that acts through a receptor-signal transduction pathway comprising a PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE 1-like (PYL)–PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE 2C (PP2C)–SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE 2 (SnRK2) module. Early-diverging aeroterrestrial algae mount a dehydration response that is similar to that of land plants, but that does not depend on ABA: Although ABA synthesis is widespread among algal species, ABA-dependent responses are not detected, and algae lack an ABA-binding PYL homolog. This raises the key question of how ABA signaling arose in the earliest land plants. Here, we systematically characterized ABA receptor-like proteins from major land plant lineages, including a protein found in the algal sister lineage of land plants. We found that the algal PYL-homolog encoded by Zygnema circumcarinatum has basal, ligand-independent activity of PP2C repression, suggesting this to be an ancestral function. Similarly, a liverwort receptor possesses basal activity, but it is further activated by ABA. We propose that co-option of ABA to control a preexisting PP2C-SnRK2-dependent desiccation-tolerance pathway enabled transition from an all-or-nothing survival strategy to a hormone-modulated, competitive strategy by enabling continued growth of anatomically diversifying vascular plants in dehydrative conditions, enabling them to exploit their new environment more efficiently.

Abscisic acid (ABA) is best known for its function as a stress-related metabolite and is ubiquitous throughout the plant kingdom (1, 2). ABA is perceived by the START domain PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE 1/PYR1-LIKE/REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR (PYR/PYL/RCAR) proteins that interact with members of the clade A (PP2C)–protein phosphatase family (3–5). PYL binding to ABA promotes formation of a receptor-ABA-PP2C ternary complex that suppresses the dephosphorylation activity of PP2Cs (6–9). This releases SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE 2s (SnRK2s) from an otherwise inhibitory complex with PP2Cs, initiating phosphorylation of transcription factors and ion channels (10, 11). The involvement of SnRK2-mediated phosphorylation in abiotic stress has been described in green algae, bryophytes, and angiosperms, and modulation of SnRK2 activity by PP2Cs is highly conserved (12–15).

According to data from Arabidopsis, ABA receptors have been divided into 3 subfamilies: I, II, and III (4). Subfamilies I and II receptors are monomeric, whereas subfamily III receptors are dimeric and exclusive to the more recently diverged angiosperms (16). The appearance of dimeric receptors represents a dramatic evolutionary change in the perception of ABA. These subfamily III receptors require ABA for dimer dissociation, which results in low basal receptor activity in the absence of ABA (17). In planta, this results in a steep threshold between stress-sensitized versus relaxed physiology. Based on the evolutionary changes in the ABA perception apparatus from bryophytes to angiosperms, and on the fact that the ABA molecule preceded the emergence of ABA receptors (2, 18), we reasoned that investigating the evolution of PYL function could illuminate how ABA evolved as a hormone modulating plant stress responses during the emergence of land plants.

Results and Discussion

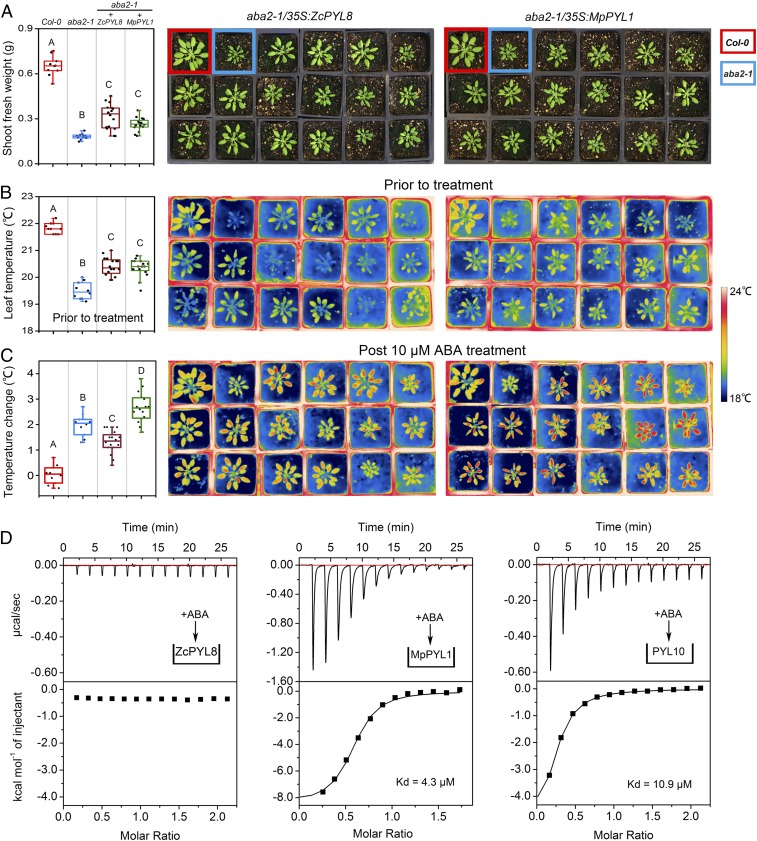

Algal ABA biology presents a dilemma: The presence of ABA has been confirmed in many species; however, algal genomes largely do not encode PYR/L ABA receptors. Recently, the Zygnema circumcarinatum alga was shown to express a transcript encoding a protein apparently orthologous to PYR/Ls, designated ZcPYL8 (19). To verify that ZcPYL8 is not an outlier of this species, we mined transcriptome resources and identified 10 more transcripts with homology to PYR/Ls in 4 genera: Zygnema, Zygnemopsis, Spirogyra, and Mesotaenium (SI Appendix, Figs. S1A and S2). The sequence analysis pointed to several amino acid differences in the otherwise conserved, key ABA-binding residues identified in bona fide land plant ABA receptors (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). To test whether ZcPYL8 functions as an ABA receptor, we performed yeast 2-hybrid and in vitro phosphatase inhibition assays with clade A PP2Cs. The ZcPYL8 protein interacted with and inhibited both native and Arabidopsis PP2Cs, but in an ABA-independent manner (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4A); notably, PP2C activity was reduced in a PYL concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). This contrasted with land plant ABA receptors in which the ABA-triggered allosteric binding to PP2C and the inhibition of phosphatase activity were evident. To find out whether ZcPYL8 is sufficient for enhanced ABA signaling in planta, we expressed the latter in the Arabidopsis aba2-1 ABA-deficient mutant background. We reasoned that under controlled growth conditions and in the absence of ABA, stress-signaling would principally be governed by the basal receptor activity. We monitored the phenotype of the transformed lines by means of fresh weight accumulation and canopy temperature. Expression of ZcPYL8 partially rescued the mutant phenotype, exemplifying the basal activity of the algal PYL (Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Moreover, application of ABA did not result in an enhanced response compared with the response registered in aba2-1 (Fig. 2C). By contrast, expression of ABA-responsive MpPYL1 enhanced ABA response in comparison with aba2-1 (Fig. 2C) (20), suggesting that ZcPYL8 activates ABA signaling in planta in an ABA-independent fashion. An isothermal titration calorimetry assay, performed to determine whether ZcPYL8 can bind ABA, showed no thermal signature, whereas titration of liverwort MpPYL1 or Arabidopsis PYL10 with ABA resulted in an exothermic reaction (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6), suggesting that ZcPYL8 is exceptionally not regulated by ABA. By mutating the obvious residues that differ between land plants and algae, we could not enhance ABA-induced ZcPYL8-PP2C interaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). However, it was evident that mutating ABA binding residues that do not take part in PP2C interaction seemingly did not hamper the receptor activity. This speaks to a pronounced flexibility in the ligand binding pocket; this flexibility has important implications for the evolution of ABA as the input signal that triggers the entire downstream cascade. Due to the lack of amino acid conservation in the specific ABA binding residues within the Zygnematophycean PYL clade (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B; i.e., PYR1 K59), we postulate that this ABA-independent activity apparently unique to ZcPYL8 might, in fact, attest a general ancestral feature of the algal PYLs. Furthermore, these results suggest that the inhibition of PP2C phosphatases is an ancestral function of PYR/L proteins that evolved as an ABA-independent process, before the origin of land plants. The question of the regulation of algal PYLs still remains open. Analysis of the published differential transcriptomic data on Z. circumcarinatum strain SAG 2419 challenged with extreme dehydration/desiccation stress (21) showed a modest 2-fold average up-regulation of ZcPYL8 transcript (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). As already noted by Rippin et al. (21), transcriptional regulation of core ABA signaling components is likely not the main route to initiate the alga’s signaling cascade (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Possibly, regulation can occur at the protein level, as suggested in Irigoyen et al. (22), or by activity modulation by different ligand.

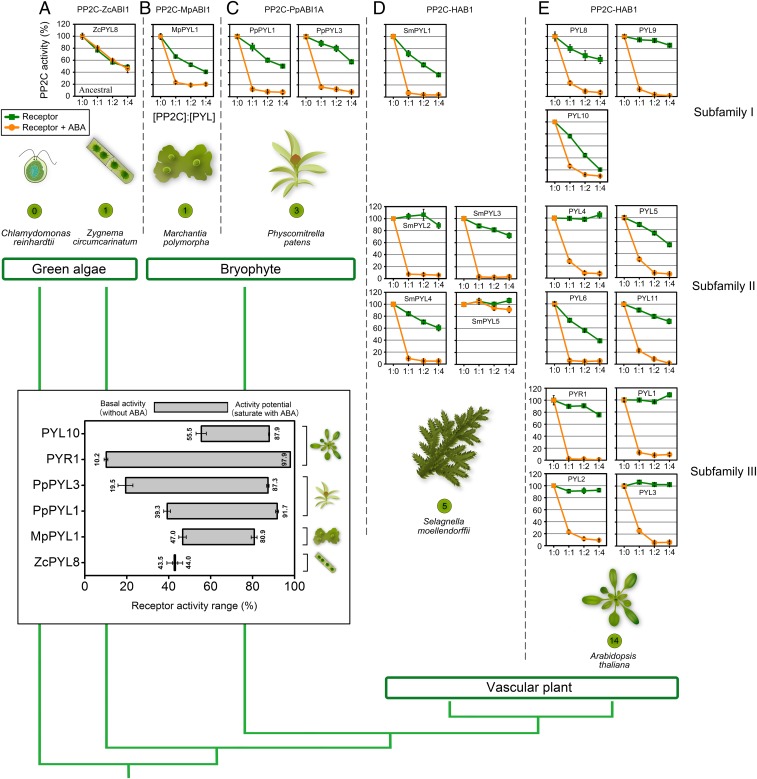

Fig. 1.

Evolution of ABA receptors indicates an increase in ABA dependency as a result of reduction of basal activity. Recombinant 6×His-Sumo-ZcPYL8 (A), 6×His-MpPYL1 (B), PpPYL1, PpPYL3 (C), SmPYL1-5 (D), PYR1, PYL1-6, PYL8, PYL10, MBP-PYL9, and MBP-PYL11 (E) were expressed in E. coli, purified, and used in PP2C activity assays with 6×His-PP2C (ZcABI1, MpABI1, PpABI1A, or HAB1). Reactions were performed with 0.5 μM 6×His-PP2C and varying concentrations of PYL (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 μM) in the absence (green) or presence (orange) of 10 μM ABA. PP2C activity is expressed as percentage of activity of PP2C in the absence of receptor. Graphs plot average values from 3 technical repeats, and error bars indicate SD. Results shown were reproduced with 3 independent protein purifications. Numbers of receptors encoded by corresponding species are shown in green circles. The phylogenetic tree of plant lineages was built according to Bowman et al. (20). The length of the branches does not indicate evolutionary dating. The inserted box depicts the dynamic response range of receptor activity. The numbers on the bar show the range of receptor activity from low at the left (without ABA) to high at the right (saturated with ABA). ZcPYL8 have no activity range. All of the values were captured at 1:2 PP2C:PYL ratio. Plant icons are not to scale.

Fig. 2.

ZcPYL8 shows basal activity but no responsiveness to ABA. ZcPYL8 or MpPYL1 were expressed under the CaMV 35S promoter in the ABA-deficient mutant aba2-1. Independent T1 plants were selected on the basis of glufosinate resistance and transplanted to soil alongside the Col-0 and aba2-1 controls (indicated by red and blue boxes, respectively). Suppression of ABA-deficient phenotype was scored visually based on phenotype and thermography, and quantified. (A–C) Phenotype of aba2-1 plants expressing ZcPYL8 or MpPYL1. (A) Fresh weight. (B and C) Leaf temperature and thermograph. B before and C, temperature change after a day after spraying with 10 μM ABA. Photographs were captured and measurements performed after 4 wk of growth under short-day conditions (8/16 day/night). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Tukey HSD test, df = 3 [P < 0.01] for transgenic plants, n = 16; for WT and aba2-1, n = 10). (D) ITC profiles and thermodynamic data from titration of ZcPYL8, MpPYL1 or PYL10 with ABA, after a series of injections of 3 μL of ABA into the ITC cell. Each peak shows the heat measured after the injection.

In pursuit of traces of this ancestral ABA-independent PYL-PP2C activity in extant land plants, we analyzed basal ABA-independent phosphatase inhibitory activity of PYR/L proteins across diverse land plant lineages, ranging from bryophytes to angiosperms. We tested the Marchantia receptor, alongside 3 Physcomitrella, 5 Selaginella, and 11 Arabidopsis receptors. Yeast 2-hybrid and phosphatase inhibition assays confirmed that land plant PYLs function as ABA receptors, as manifested by their ABA-mediated interaction with clade A PP2Cs and inhibition of PP2C activity (SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4 B–E). Next, we tested the basal activity of the aforementioned PYLs, using recombinant proteins for ABA-free receptor-PP2C inhibition assays (Fig. 1 B–E). To further normalize PP2C activity, receptors were also tested with the Arabidopsis phosphatase HAB1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). For the latter, receptors were assayed in the minimal concentration needed to obtain maximal HAB1 inhibition when saturated with ABA. The Marchantia receptor showed 30% to 50% basal activity when analyzed with the native PP2C or with the standardized HAB1 (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Physcomitrella PYLs demonstrated both ABA-induced activity and basal activity (PpPYL1, 20%; PpPYL3, 15%; Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Three of the 4 active Selaginella receptors had measurable basal activity, whereas SmPYL2 was fully ligand-dependent (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). In Arabidopsis, the monomeric receptors included receptors exhibiting a range of basal activities, whereas subfamily III dimeric receptors had no basal activity (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). A decline in basal ABA receptor activity may have broadened the dynamic range of the stress response, enabling fine-tuning of the response. The predominant role of the angiosperm-exclusive dimeric receptors (with the lowest basal activity) in the collective ABA response would therefore be a manifestation of the highest level of response range, while the contrary is the case for the single Marchantia receptor, which seemingly provides a narrow ABA response range (50% basal activity; Fig. 1 insertion).

While receptors displaying high basal activity might obscure ABA-mediated fine-tuning processes, Arabidopsis, Striga, Solanum, Oryza, and Triticum still maintain both receptors with a narrower response range alongside receptors that allow a broader range of response (23–27). Arabidopsis PYL10 stands out as an example of a receptor with high basal activity, as its regulation by ABA affects less than 50% of the response magnitude (Fig. 1E). However, we found that PYL10 expression is undetected in available transcriptome datasets, suggesting that if it is expressed during the plant life cycle, it is either at a very low level or developmentally restricted in some way. Similarly, Triticum TaPYL5 showed high basal activity in phosphatase inhibition assays, signifying that it is an ABA receptor with a narrow response range, the expression of which is also very restricted during the lifecycle of wheat (27). We therefore investigated the promoter specificity of Arabidopsis PYL10, using a 2,078-bp upstream promoter sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A) driving a VENUS reporter construct. We observed high expression and protein accumulation in leaves (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B), implying that the promoter sequence did not dictate a limited transcription pattern for PYL10. However, the 3′ end of the PYL10 gene, which contains sequences of 2 transposable elements, causes a strong transcriptional down-regulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 C–E). The suppression of PYL10 by the 3′ region likely enables higher ABA-related responsiveness in Arabidopsis, unmasking the alternative, highly tuned receptors with a broader response range.

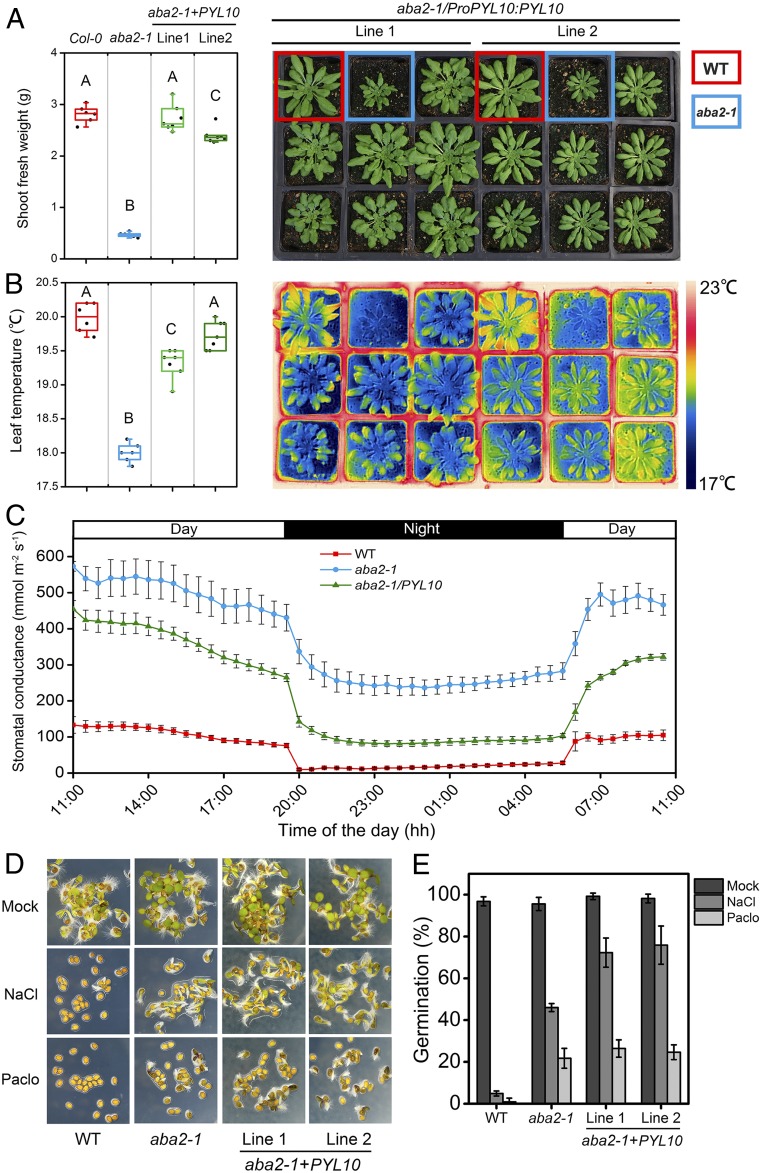

To find out whether the basal activity of PYL10, when its expression is enabled, is sufficient to activate ABA signaling, we took advantage of the aforementioned receptor/aba2-1 mutant expression system. We transformed aba2-1 with PYL10 under the regulation of its native promoter but without its 3′ region sequence. PYL10 transcription was observed in various vegetative tissues, as well as the developing seed, but not during germination (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Ectopic PYL10 expression suppressed the aba2-1 phenotype in both stature and thermal signature of the canopy, in agreement with its promoter-enabled expression pattern, as it did for seed maturation, size, and weight (Fig. 3 A–E and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Furthermore, detailed analysis of whole-plant gas exchange showed that plants expressing PYL10 had lower stomatal conductance, which was closer to wild-type levels (Fig. 3C). Expression of PYL6, MpPYL1, and ZcPYL8 driven by the PYL10 promoter resulted in similar suppression of the aba2-1 phenotype (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 and S14). In contrast, the expression of PYR1, an entirely ABA-dependent dimeric Arabidopsis receptor with low basal activity, did not suppress the aba2-1 phenotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Thus, in the absence of external ABA, high basal receptor activity can drive what is normally the ABA response, which would otherwise have been regulated by the highly tuned dimeric receptors dominating the adaptive response in the presence of stress-triggered ABA.

Fig. 3.

Basal activity of PYL10 is sufficient to trigger ABA physiological response. (A) Phenotype and fresh weight of wild-type (WT) (Col-0), aba2-1, and aba2-1 mutants expressing PYL10. (B) Thermograph and leaf temperature of WT, aba2-1, and PYL10 transgenic plants. Photographs were taken after 6 wk of growth under short-day conditions (8/16 day/night). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between transgenic plants and aba2-1 controls (Tukey HSD test, df = 3 [P < 0.01] for transgenic plants, n = 7; for WT and aba2-1, n = 6). (C) Diurnal changes in stomatal conductance of Col-0, aba2-1, and PYL10-expressing transgenic lines. Plants were kept in a whole-rosette gas exchange measurement device, and stomatal conductance was monitored during a diurnal light/dark cycle. (D and E) Seeds of each genotype were stratified for 4 d at 4 °C on agar medium containing 5 μM paclobutrazol (Pac) or 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl). Germination was scored 60 h postimbibition. Representative images were showed in D. Values plotted in E are average of 3 independent experiments, and error bars indicate SD.

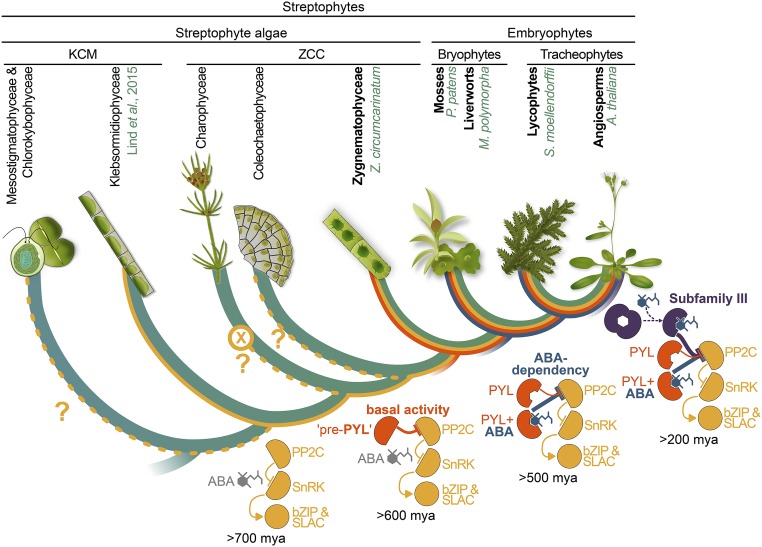

Combined with the phylogenetic relationship between PYL homologs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), our results suggest that the ancestral function of PYLs was likely an ABA-independent PP2C inhibitory activity (Fig. 4). Along the evolutionary trajectory leading to the last common ancestor of land plants, PYL proteins with basal activity gained ABA interactivity (Fig. 4). Interestingly, in case of the evolution of the auxin signaling cascade, Martin-Arevalillo and colleagues recently proposed a similar scenario that entails the modular evolution of a phytohormonal signaling cascade from a phytohormone-independent origin in streptophyte algae (28). During the evolution and diversification of land plants, the PYL protein family has expanded in a lineage-specific manner, giving rise to various character states of basal as well as ABA-dependent activity. Most recently, angiosperms gained another layer of ABA dependency with the dimeric PYLs (Fig. 4). This suggests that a dampening of the basal activity of the receptors was a driving force for the evolution of ABA responsiveness in land plant PYLs.

Fig. 4.

Proposed scenario of the step-wise evolution of the role of PYL proteins in the PP2C-SnRK2s cascade. The monophyletic streptophyte lineage comprises the land plants and the ZCC-grade and KCM-grade charophyte algae (green cladogram) (32). All the signal-transduction and downstream targets of ABA signaling (PP2C, SnRK2s, transcription factors [bZIP], and ion channels [SLAC1] are present at the base of the streptophyte clade). All these algae also probably synthesize the ABA molecule (gray). Heterologous expression analysis of KCM algal (Klebsormidium nitens) components indicated existence of a regulatory “wiring” with these 3 components (yellow line), suggesting its emergence already in KCM algae. Our data showed that with the gain of the PYL proteins in a common ancestor of land plants and Zygnematophyceae, the basal, ABA-independent, PP2C-inhibitory activity of PYLs was gained (orange line). The Zygnematophycean PYL homologs appear to only have basal activity, hence designating them pre-PYL. Along the evolutionary trajectory from the algal progenitor to the last common ancestor of land plants, the basal PP2C-inhibitory activity of PYLs became supplemented by ABA-dependent activity (blue line). In angiosperms, another layer of regulation was gained with the dimeric subfamily III PYLs (purple line). All dating is based on Morris et al. (33). Species names of the streptophytes used in this study are highlighted in green.

In the broader sense, terrestrial stresses would have presented major challenges for the earliest land plants (29, 30). While the ability to survive desiccation would have been a necessary trait in the algal precursors of the land plants, this would be less desirable in their anatomically more complex descendants. Vegetative desiccation ceases to be a competitive evolutionary strategy when set against maintaining growth by using a hormone to initiate a range of intermediate responses. Indeed, desiccation tolerance, implying the loss of all internal water, becomes a threat to survival if the continuity of the vascular system is compromised (31). In light of the presented findings, we propose that ABA-mediated fine-tuning of the PP2C–SnRK2 signaling cascade was a key evolutionary novelty, an added layer of regulation that aided these plants in their conquest of land (Fig. 4).

Materials and Methods

Plant Material.

Arabidopsis thaliana aba2-1 mutant strain and its background wild-type strain Columbia (Col-0) (34) were used. Unless otherwise indicated, Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown in a growth chamber (Percival Scientific USA) under short-day conditions (8 h light and 16 h dark) and a controlled temperature of 20 °C to 22 °C, with 70% humidity and light intensity of 70 to 100 μE·m−2·s−1.

DNA Sequence.

Coding sequences of ZcPYL8, MpPYL1, PpPYL1-3, SmPYL1-5, ΔN ZcABI1 (lacking N-terminal amino acids 1 to 247), ΔN MpABI1 (lacking residues 1 to 224), and SmABI1 were chemically synthesized (SI Appendix, Table S1). The PYL10 promoter (2,078 bp upstream from the PYL10 start codon) and the genomic sequences of PYL10, PYL6, and PYR1 were amplified from Col-0 genomic DNA. The coding sequence of PYL10 was amplified from cDNA isolated from Col-0 seedlings. All sequences were amplified using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs), with the exception of the PYL10 3′ end (733 bp after the stop codon), which was amplified using KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA Polymerase (Roche).

Phylogenetic Analyses of PYL Sequences.

To generate the dataset of PYL sequences, streptophyte algal transcriptomes were downloaded from the 1KP data (35), and a tBLASTn search was performed using all Arabidopsis thaliana PYLs as well as the Z. circumcarinatum ZcPYL8 as queries. For the land plants, whole-genome data of Physcomitrella patens (36), Marchantia polymorpha (20), Selaginella moellendorffii (37), Azolla filiculoides (38), Picea abies (39), Triticum aestivum (International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2018), Oryza sativa (40), and Solanum lycopersicum (Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012) were downloaded. The 14 PYR/PYL/RCAR sequences from the Arabidopsis thaliana TAIR10 release were used as queries for a BLASTp search of land plant proteomes to obtain the PYL sequences. For O. sativa, and S. lycopersicum, the previously described PYL sequence annotation was used (25, 41). Incomplete and strongly truncated sequences were removed, and sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.305b (42) and the L-INS -I settings. The tree was computed using IQ-TREE multicore version 1.5.5 (Linux 64-bit built June 2, 2017) (43), with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. This run included a determination of the best model, using ModelFinder (44). ModelFinder computed log-likelihoods for 144 protein substitution models and retrieved the lowest Akaike Information Criterion, Corrected Akaike Information Criterion, and Bayesian Information Criterion for JTT+G4, which was hence solicited as the best model and used for computing the tree.

Yeast Two-Hybrid.

The coding regions of receptors were cloned into pBD-GAL4 (Clontech) fused to the GAL4 binding domain. PP2Cs were cloned into pACT (Clontech), which expresses as a GAL4 activation domain protein fusion. Both pBD-GAL4 and pACT were cotransformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Y190, and positive colonies were selected on synthetic dextrose agar medium, lacking Leu and Trp. Strains expressing receptor PP2C–combination were plated onto synthetic dextrose-Leu and Trp containing 10 μM ABA or 0.1% DMSO as mock control. After incubation at 30 °C for 2 d, interaction was visualized by X-gal staining to monitor b-galactosidase reporter gene expression, as described previously (4).

Receptor-Mediated PP2C Inhibition Assay.

The coding sequences of MpPYL1, PpPYL1-3, SmPYL1-5, PYL10CA, ΔN ZcABI1, and ΔN MpABI1 were cloned into the pET28 vector, and ZcPYL8 was cloned into a pSUMO fusion vector, generating 6×His-tagged proteins. PYR1 and PYL1 to PYL11 (except for PYL7) were described previously (45). ΔN HAB1 (lacking N-terminal amino acids 1 to 178) was used to obtain 6 × His-fused PP2C (46). Proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS (Promega) E. coli strain. For PYLs, transformed cells were precultured overnight and then transferred into 500 mL terrific broth medium and cultured at 30 °C to OD600 = 0.9. IPTG (1 mM) was added, and cultures were further incubated at 15 °C, overnight. For PP2C, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM IPTG were added at OD600 = 0.9, and samples were further incubated overnight, at 18 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, suspended in buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl at pH 8.0) plus 10 mM imidazole and stored at −80 °C. Cells were broken by 2 freeze–thaw cycles followed by sonication for 60 s. Centrifugation was performed, and cleared supernatant was loaded onto Ni-NTA agarose (Cube biotech), which was then washed with buffer A supplemented with 30 mM imidazole. Proteins were eluted with buffer A plus 250 mM imidazole. Recombinant proteins were dialyzed with 1 × TBS (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.5), 20% glycerol, in 4 °C, overnight. For purification of PP2C, 1 mM MgCl2 was added to all buffers. A receptor-mediated PP2C inhibition assay was performed as previously described (47). Reactions comprised 0.5 μM PP2C and 0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM receptor and 33 mM Tris·acetate (pH 7.9), 66 mM potassium acetate, 0.1% BSA, 10 mM MnCl2, 0.1% β-ME, and 50 mM pNPP in the absence or presence of 10 μM ABA. Hydrolysis of pNPP was monitored at A405 by Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek). PP2C activity in the absence of receptor was set as 100% activity. The ABA dose-dependent PP2C inhibition assay was conducted as previously described (45), using 0.5 μM PP2C, and 1 μM receptor. ABA was added at 0, 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 1, and 10 μM. PP2C activity in the presence of receptor and absence of ABA was set as 100% activity. All experiments were performed with 2 independent protein preparations.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry.

Proteins for isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) were dialyzed with ITC buffer containing 20 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. PYL10, MpPYL1, and ZcPYL8 were assayed at concentrations of 110, 140, and 45 μM, respectively. Protein solution in the cell was titrated with the ligand (+)ABA dissolved in the dialysis buffer. The concentrations of ABA stock in the injection syringe for PYL10, MpPYL1, and ZcPYL8 were 1.1, 1.4, and 0.45 mM, respectively, and the final diluted ligand concentration was 2-fold higher than that of the protein. ITC experiments were executed in ITC200 by a series of injections of 3 μL ABA into the ITC cell containing PYL, and heat was measured after the injection. The calorimetric analysis program in the Origin suite was used for data evaluation and presentation.

qRT-PCR.

Arabidopsis leaf tissue was harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN) followed by DNase digestion using the AMBION DNA-free Kit (Life Technologies), according to manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA from 1,000 ng total RNA was synthesized using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green ROX Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a Rotor-Gene Q system (Qiagen). Samples were heated to 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s Results were analyzed with Rotor-Gene Q Series software (Qiagen), using the ΔΔCT method.

Western Blot.

Total proteins were extracted from liquid nitrogen-frozen tissue followed by SDS/PAGE separation and transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. The presence of HPB-fused protein was detected with 1:5,000 streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (GE). Images were acquired using ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE) and were analyzed with ImageQuant TL 1D v8.1 software (GE).

ABA-Deficient Mutant Phenotype Suppression Assay.

For 35S promoter-driven ZcPYL8 and MpPYL1, coding sequences of ZcPYL8 and MpPYL1 were cloned into pEGHPB under the control of 35S promoter. For PYL10 promoter-driven receptors, the 35S promoter was replaced by 2,078-bp upstream sequence of PYL10. Then, the coding sequences of ZcPYL8, MpPYL1, PYR1, PYL6, and PYL10 were cloned into the above-mentioned vector under the control of PYL10 promoter. Constructs were stably transformed into the Arabidopsis ABA-deficient mutant, aba2-1. Sixteen independent T1 transformants for each construct were selected based on glufosinate resistance. Fresh weight and leaf temperature were monitored after 2 mo of growth under short-day conditions. Two independent T3 single-copy lines expressing PYL10 were obtained for gas exchange experiments.

Thermal Analysis.

Two-month-old Arabidopsis plants grown in growth chambers at 22 °C, 10 h light/14 h dark were using for thermal analysis. The thermal images of the plants were taken at 10 AM, using a FLIR T630 camera (FLIR). Canopy temperature of plants was measured with Flir Tools v5.2.15161.1001 software (FLIR). Each dot in box plots represents means of 8 to 10 measurements of an individual plant.

Gas Exchange Experiments.

For gas exchange experiments, Arabidopsis seeds were planted in soil containing 2:1 (v:v) peat:vermiculite and grown well-watered in growth chambers (Snijders Scientific, Drogenbos, Belgia), under 12/12 photoperiod, 23°/18 °C temperature, 150 µmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 light and 70% relative humidity conditions, and were 25 to 30 d old during experiments. Whole-rosette stomatal conductances were recorded with an 8-chamber custom-built temperature-controlled gas-exchange device analogous to the one described before. Plants were inserted into the measurement cuvettes and allowed to stabilize at standard conditions: ambient CO2 (∼400 ppm), light 150 µmol⋅m−2⋅s−1, and relative air humidity (RH) ∼60 ± 5%. In diurnal experiments, the dark period lasted from 8 PM to 8 AM, similar to growth chamber conditions. In ABA treatment experiments, 5 μM ABA with 0.012% Silwet L-77 (Duchefa) and 0.05% ethanol was sprayed on the leaves, and plants were put back into cuvettes and for continued measurement of leaf conductance. Photographs of plants were taken after the experiment, and leaf rosette area was calculated using ImageJ 1.37 v (National Institutes of Health). Stomatal conductance for water vapor was calculated with a custom-written program, as previously described (48).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Mutants were generated using the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Sequences of mutagenesis primers are provided in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Statistical Analysis.

All data were statistically analyzed using JMP pro 12 statistical package (SAS Institute). Tukey HSD (honestly significant difference) test was used for fresh weight, leaf temperature, seed length, and hundred-seed weight analysis. Student’s t test was used for qRT-PCR analysis. All box plots, bar graphs, and connecting lines were generated using Origin 8.1 Software.

Data Availability.

Primers, sequences, and accession numbers of genes analyzed in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Tables S1–S3. Seeds of transgenic lines used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sean Cutler, Idan Efroni, Ori Naomi, and Shahal Abbo for the insightful discussions and for commenting on the ideas presented here. We thank Oded Pri-tal for graphic assistance. We thank Profs. Burkhard Becker (University of Cologne) and Andreas Holzinger (University of Innsbruck) for help in accessing raw RNA sequencing data on Zygnema. This research was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (661/18), Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund (IS-4919-16 R), and German-Israel Foundation, Young Scientists’ Program (I-2410-203.13/2016). Y.S. was supported partly by the Lady Davis Fellowship Trust for the award of a Golda Meir Fellowship. J.d.V. thanks the German Research Foundation for a Return Grant (VR132/3-1) and the European Research Council for funding under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 852725; ERC-StG “TerreStriAL”). E.M. and H.K. were supported by the Estonian Research Council (PUT1133).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1914480116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nambara E., Marion-Poll A., Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 165–185 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser F., Waadt R., Schroeder J. I., Evolution of abscisic acid synthesis and signaling mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 21, R346–R355 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Y., et al. , Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324, 1064–1068 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S. Y., et al. , Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324, 1068–1071 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Finkelstein R. R., Abrams S. R., Abscisic acid: Emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 651–679 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melcher K., et al. , A gate-latch-lock mechanism for hormone signalling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature 462, 602–608 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyazono K., et al. , Structural basis of abscisic acid signalling. Nature 462, 609–614 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santiago J., et al. , The abscisic acid receptor PYR1 in complex with abscisic acid. Nature 462, 665–668 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin P., et al. , Structural insights into the mechanism of abscisic acid signaling by PYL proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1230–1236 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soon F. F., et al. , Molecular mimicry regulates ABA signaling by SnRK2 kinases and PP2C phosphatases. Science 335, 85–88 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyakawa T., Fujita Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Tanokura M., Structure and function of abscisic acid receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 259–266 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Ballester D., Pollock S. V., Pootakham W., Grossman A. R., The central role of a SNRK2 kinase in sulfur deprivation responses. Plant Physiol. 147, 216–227 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii H., Zhu J. K., Arabidopsis mutant deficient in 3 abscisic acid-activated protein kinases reveals critical roles in growth, reproduction, and stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8380–8385 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lind C., et al. , Stomatal guard cells co-opted an ancient ABA-dependent desiccation survival system to regulate stomatal closure. Curr. Biol. 25, 928–935 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinozawa A., et al. , SnRK2 protein kinases represent an ancient system in plants for adaptation to a terrestrial environment. Commun. Biol. 2, 30 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umezawa T., et al. , Molecular basis of the core regulatory network in ABA responses: Sensing, signaling and transport. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1821–1839 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupeux F., et al. , A thermodynamic switch modulates abscisic acid receptor sensitivity. EMBO J. 30, 4171–4184 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartung W., The evolution of abscisic acid (ABA) and ABA function in lower plants, fungi and lichen. Funct. Plant Biol. 37, 806–812 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vries J., Curtis B. A., Gould S. B., Archibald J. M., Embryophyte stress signaling evolved in the algal progenitors of land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E3471–E3480 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowman J. L., et al. , Insights into land plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell 171, 287–304 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rippin M., Becker B., Holzinger A., Enhanced desiccation tolerance in mature cultures of the streptophytic green alga Zygnema circumcarinatum revealed by transcriptomics. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 2067–2084 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irigoyen M. L., et al. , Targeted degradation of abscisic acid receptors is mediated by the ubiquitin ligase substrate adaptor DDA1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 712–728 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao Q., et al. , The molecular basis of ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs by a subclass of PYL proteins. Mol. Cell 42, 662–672 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.González-Guzmán M., et al. , Tomato PYR/PYL/RCAR abscisic acid receptors show high expression in root, differential sensitivity to the abscisic acid agonist quinabactin, and the capability to enhance plant drought resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4451–4464 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Y., et al. , Identification and characterization of ABA receptors in Oryza sativa. PLoS One 9, e95246 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujioka H., et al. , Aberrant protein phosphatase 2C leads to abscisic acid insensitivity and high transpiration in parasitic Striga. Nat. Plants 5, 258–262 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mega R., et al. , Tuning water-use efficiency and drought tolerance in wheat using abscisic acid receptors. Nat. Plants 5, 153–159 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin-Arevalillo R., et al. , Evolution of the auxin response factors from charophyte ancestors. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008400 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delwiche C. F., Cooper E. D., The evolutionary origin of a terrestrial flora. Curr. Biol. 25, R899–R910 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuming A. C., Stevenson S. R., From pond slime to rain forest: The evolution of ABA signalling and the acquisition of dehydration tolerance. New Phytol. 206, 5–7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderegg W. R., Spatial and temporal variation in plant hydraulic traits and their relevance for climate change impacts on vegetation. New Phytol. 205, 1008–1014 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Vries J., Archibald J. M., Plant evolution: Landmarks on the path to terrestrial life. New Phytol. 217, 1428–1434 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris J. L., et al. , The timescale of early land plant evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E2274–E2283 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Léon-Kloosterziel K. M., et al. , Isolation and characterization of abscisic acid-deficient Arabidopsis mutants at two new loci. Plant J. 10, 655–661 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matasci N., et al. , Data access for the 1,000 Plants (1KP) project. Gigascience 3, 17 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rensing S. A., et al. , The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 319, 64–69 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banks J. A., et al. , The Selaginella genome identifies genetic changes associated with the evolution of vascular plants. Science 332, 960–963 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F. W., et al. , Fern genomes elucidate land plant evolution and cyanobacterial symbioses. Nat. Plants 4, 460–472 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nystedt B., et al. , The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature 497, 579–584 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouyang S., et al. , The TIGR rice genome annotation resource: Improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D883–D887 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen P., et al. , Interactions of ABA signaling core components (SlPYLs, SlPP2Cs, and SlSnRK2s) in tomato (Solanum lycopersicon). J. Plant Physiol. 205, 67–74 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katoh K., Standley D. M., MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen L. T., Schmidt H. A., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q., IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B. Q., Wong T. K. F., von Haeseler A., Jermiin L. S., ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamoto M., et al. , Activation of dimeric ABA receptors elicits guard cell closure, ABA-regulated gene expression, and drought tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12132–12137 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saez A., Rodrigues A., Santiago J., Rubio S., Rodriguez P. L., HAB1-SWI3B interaction reveals a link between abscisic acid signaling and putative SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 2972–2988 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosquna A., et al. , Potent and selective activation of abscisic acid receptors in vivo by mutational stabilization of their agonist-bound conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20838–20843 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kollist T., et al. , A novel device detects a rapid ozone‐induced transient stomatal closure in intact Arabidopsis and its absence in abi2 mutant. Physiol. Plant. 129, 796–803 (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Primers, sequences, and accession numbers of genes analyzed in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Tables S1–S3. Seeds of transgenic lines used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.