Abstract

Objective. To implement a continuous professional development (CPD) program in the didactic curriculum of a three-year Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program, and evaluate associated outcomes.

Methods. The initial CPD program was implemented in the didactic curriculum of the PharmD program in 2014-2015. Barriers were identified and strategies adopted to overcome the barriers. A revised CPD curriculum was implemented in the 2015-2016 academic year. Student and faculty evaluations of the course were conducted, and students’ perceived capabilities in the various skills related to professional development were measured.

Results. The student ratings of the course were acceptable (ranging from 3.3 to 4.2 on a 5-point Likert scale). First-year students rated the course higher than second-year students did. The majority of faculty members found the CPD curriculum valuable for students. Students perceived that their skills in oral, written and interprofessional communication, leadership, and time management had significantly improved after completing the course.

Conclusion. Implementation of a CPD process during the didactic curriculum for PharmD students is feasible and beneficial to students’ professional development. This CPD model provided students with an opportunity to develop self-directed lifelong learning skills and prepared them to transition to practice-based learning in their final year of the program.

Keywords: continuing pharmacy education, continuing professional development, pharmacy students

INTRODUCTION

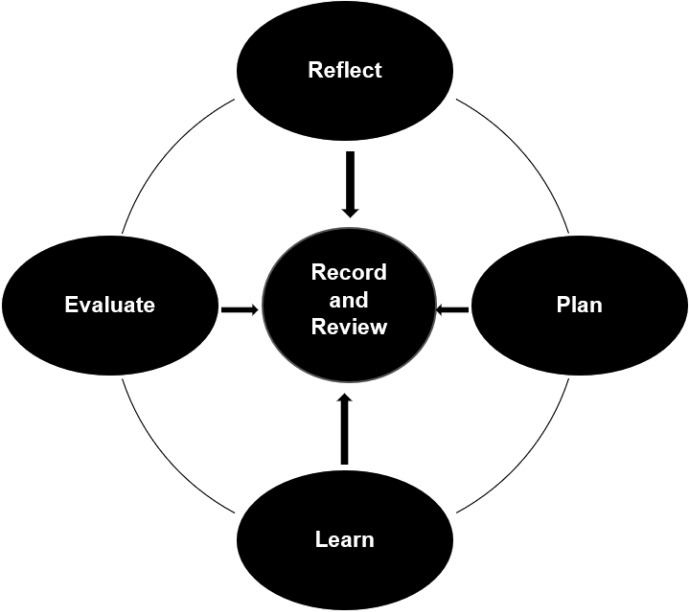

The pharmacy profession is rapidly changing as the role of pharmacists in the US health care system continues to evolve. Given the rapid medical and technological advances that also are occurring, it is imperative for pharmacists to become lifelong learners. In a 2009 report, the Institute of Medicine emphasized the importance of lifelong learning in health care and concluded that the education and training of health care professionals must be competency based.1 In pharmacy, continuing education (CE) is the traditional and primary means by which pharmacists pursue learning and maintain their knowledge, skills, and competencies after they have entered the profession. Although CE programs are well established, there is mixed results regarding the outcomes from CE in successfully changing the practice behaviors.2 Continuing professional development (CPD) is an alternative approach that can help pharmacists and pharmacy students meet and maintain defined competencies in areas relevant to their respective professional responsibilities and develop the necessary habits of self-directed lifelong learning. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) defines CPD as “a self-directed, ongoing, systematic and outcomes-focused approach to lifelong learning that is applied into practice. It involves the process of active participation in formal and informal learning activities that assist in developing and maintaining competence, enhancing professional practice, and supporting achievement of career goals.”3 The steps in the CPD cycle are described in Figure 1.3

Figure 1.

The CPD Cycle

While pharmacists’ professional education begins in pharmacy school, it must be continually developed through in-service training, hands-on experience, and other lifelong learning activities. As outlined in ACPE Standards 2016, colleges and schools of pharmacy must provide an environment and culture that promotes self-directed lifelong learning in students.4 Continuous professional development serves as a model that can be adopted by pharmacists and student pharmacists to foster and support self-directed, lifelong learning. The benefits of implementing a CPD curriculum address the requirements of Domain 4 of the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) 2013 Educational Outcomes and Standard 4 of the ACPE standards on personal and professional development.5

The principles of CPD have already been incorporated into curricula at several colleges of pharmacy in the United States.6-10 Continuous professional development can be threaded through didactic and experiential education, helping tie the curriculum together and allowing students to individualize aspects of their education and practice experiences. Implementation strategies and the professional and regulatory framework within which the CPD model is adopted differ considerably between institutions. For example, the University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy and University of Maryland School of Pharmacy implemented CPD programs during experiential rotations.7,8 While Wegman’s School of Pharmacy at St. John Fisher College implemented a CPD process in the first year of the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum, Belmont University College of Pharmacy implemented their CPD program as part of a terminal capstone course.9,10 At the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy, students enroll in a CPD course that runs concurrently with advanced pharmacy practice experiences.8 Several studies have suggested that incorporation of CPD early in the curriculum makes it easier for pharmacy students to adopt lifelong learning using CPD principles.11-13

Roseman University College of Pharmacy (RUCOP) implemented our CPD program as part of the didactic curriculum of the three-year PharmD program in fall 2014. At RUCOP, the first two years are focused on the didactic curriculum and the third year is focused on advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). The CPD program was introduced to students in the first year and continued through the second year. This article describes the feasibility of implementing a CPD program within the didactic curriculum, barriers faced while implementing the program, strategies adopted to overcome the barriers, and the outcomes from the process. The Roseman University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt from review.

METHODS

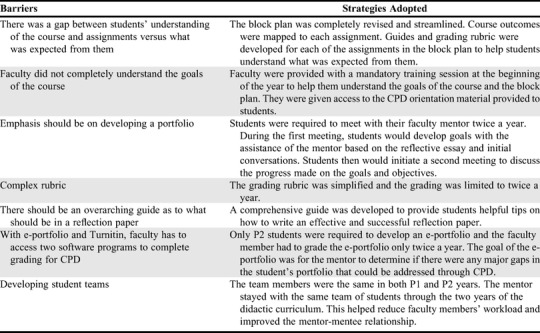

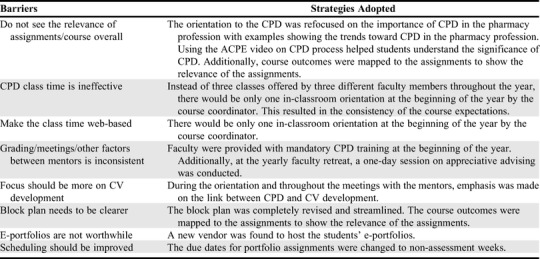

In fall 2014, the Roseman University College of Pharmacy implemented a CPD program for all first-year pharmacy students (P1), and in the 2015-2016 academic year, the program was extended to second-year students (P2). Qualitative feedback was gathered from faculty members and students regarding their experience with the course including recommendations to improve the course. At the end of the first year of the CPD program (end of 2014-2015 academic year), feedback and recommendations regarding the course were collected from the faculty members. A survey was sent to all faculty mentors (n=16) with open-ended questions that focused on the utility of the CPD block plan (course syllabus), portfolio assignments, grading responsibilities, ease of use of the grading rubric, facilitators and barriers in mentoring, overall thoughts about the course, and suggestions for changes. The major barriers, suggested recommendations, and the adopted strategies to improve the course based on the feedback are provided in Table 1. At the end of the 2015-2016 academic year (after one class of students completed both years of the program), feedback was collected using an open-ended survey from both P1 (n=103) and P2 (n=97) students to understand their perceptions about the program and what needed to be done to improve it. The open-ended survey had one question: “Knowing that the knowledge and skills acquired from this course is instrumental in becoming a pharmacist, if you could change anything about this course, what would you change, how would you change them, and why would you make the change?” The detailed responses from the 43 students who responded to the open-ended survey are listed in Table 2. Based on the feedback and recommendations, the course underwent a major revision at the end of the 2015-2016 academic year.

Table 1.

Faculty Feedback Received at the End of the First Academic Year in Which a Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Course for PharmD Students Was Implemented

Table 2.

Student Feedback at the End of the First Academic Year (2015-2016) in Which a Continuing Professional Development Course (CPD) for PharmD Students Had Been Implemented

The revised course design was implemented in the 2016-2017 academic year. At the beginning of the school year, a short introduction to CPD was provided to both P1 and P2 students during the orientation program. This was followed by a classroom lecture on CPD by the course coordinator for both classes. For the P1 class, the CPD lecture was for two hours and 30 minutes, and for the P2 class, it was for one hour. The following content areas were discussed during orientation: definition of CPD, CPD process, advantages of using CPD to maintain competence in pharmacy school, benefits of mentoring for personal and professional development, and the block plan and portfolio assignments for the course. The CPD video created by ACPE was used to introduce the CPD program to P1 students. For the P2 students, the orientation was more of a refresher course on CPD and the block plan. At the end of the orientation, students were given a quiz on the open-block plan, and points were assigned based on a sliding scale on the quiz score. Students could earn a maximum of 10 points if they earned more than 90% on the quiz and one point if they earned less than 40%. The portfolio assignments included: beginning of course reflection for P1 and P2, including an e-portfolio for P2 students; goals and objectives development for P1 and P2, including personal SWOT analysis for P2; and end of course reflection for P1 and P2.

All students were assigned a faculty mentor at the beginning of the P1 year by the course coordinator. Faculty mentors were assigned to oversee the CPD process for a group of 10 to 12 students during the course, in addition to fulfilling their usual student advising responsibilities. The mentor stayed with the same students through the two years of didactic curriculum. The mentors worked closely with the P1 students in their CPD process, including with goal development because they were new to the process. When the students began their P2 year, the role of the mentor was more to guide students rather than to “hold their hands.” The mentors also had to grade the portfolio assignments associated with the CPD program. All students had to meet with their mentor face to face or by email or phone at least two times during the year and more if needed.

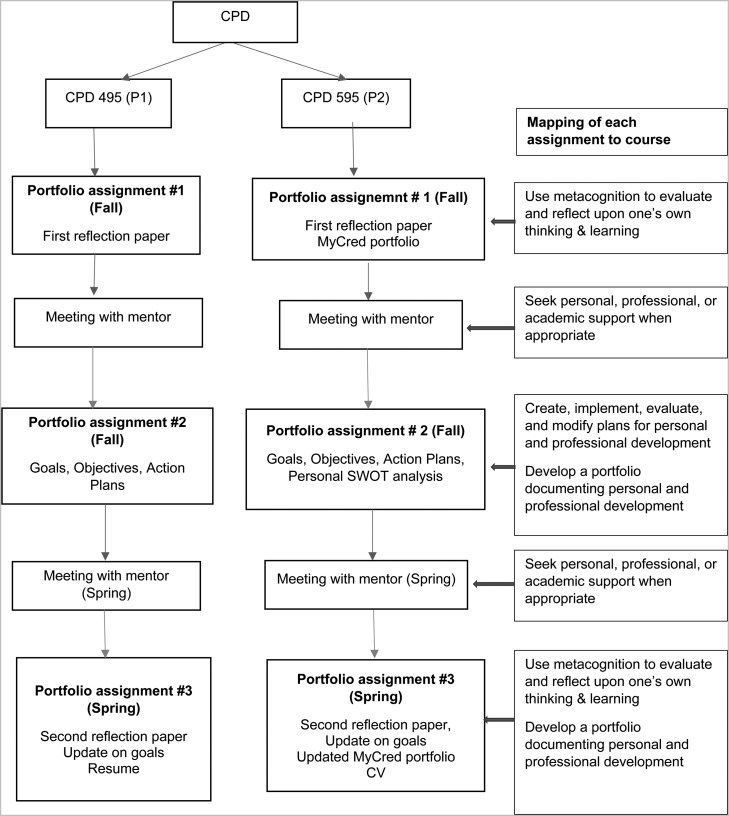

The course was structured around three portfolio assignments, the open-block plan quiz, two mandatory mentor meetings, and optional attendance at professional development activities. Each portfolio assignment was designed to enable the students to demonstrate completion of course-specific outcomes (Figure 2). Students were provided detailed instructions for each of the portfolio assignments at the start of the course during the class instruction, including performance criteria, grading rubrics, and due dates. There was no midpoint or final examination, and the course used RUCOP’s pass/fail grading system. The course used a point system to account for student progress, and students were required to achieve at least 90 points to pass the course. The completion of the portfolio assignments and the quiz in this course counted to only a maximum of 94 points. An unlimited number of optional points could be earned from completing professional development activities. Points achieved from professional development activities could make the students eligible to receive honors for the CPD course. To obtain honors, the student had to achieve 95 points; therefore, students had to participate in professional development activities for additional points even if they achieved the maximum points for the portfolio assignments and quiz. Students could attend professional development activities held at the RUCOP or outside of the college to earn points during the year. Points were calculated cumulatively, with final scores assessed at the end of the P1 and P2 years. Successful completion of the CPD course was required to matriculate to the next year of the program.

Figure 2.

CPD Portfolio Assignments and Mapping of Each Assignment to the Course Outcomes for the Didactic Curriculum

The three portfolio assignments that P1 and P2 students were required to complete are outlined in Figure 2. The portfolios created by students were regularly assessed by faculty members and graded two times. The portfolios were created in a single Word document. Each new assignment was added to the same document, which contained all previous CPD assignments for the year, including previous revisions of assignments. The portfolio assignments were uploaded to Turnitin (Oakland, CA) for grading. Faculty members used a rubric to grade assignments and used Turnitin to provide feedback and scores to the students. Because grading for the course was based on an accumulative, point-based system, students were given the opportunity to revise each assignment once to improve their score. Faculty members were given three weeks to grade the initial assignments. The students were given two weeks to submit a revised assignment. If one was submitted, the faculty member graded the revision within two weeks.

The first portfolio assignment was a reflection paper that could serve as a basis for the student’s CPD and allowed the mentors to get to know the students well enough to help them with their specific CPD plan. Students were provided with a set of questions that they could use in writing their self-reflection. There was no specific length or formatting requirements for this assignment. Points were awarded for on-time submission. This assignment was due early in the fall semester, and the second assignment was due later in the fall semester. Between the first and second assignments, the students were expected to meet with their mentors and discuss their plans for CPD. For the second portfolio assignment, students were asked to submit one or more SMART goals and corresponding objectives and action plans. Goals and objectives were considered “SMART” if they were specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timed. The third portfolio assignment was due in late spring and included a second reflection paper; an update on students’ goals, objectives, and action plan statements; and a resume (for P1 students) or curriculum vitae (CV) (for P2 students). Before the submission of their third assignment, the students had to meet with faculty members to discuss progress on their CPD plan. By the third assignment, the students were expected to submit a self-reflection document that demonstrated the student’s ability to identify strengths/weaknesses and use metacognition to evaluate and reflect on their own thinking and learning experiences. The third portfolio assignment also graded students on their professionalism; seeking constructive feedback from resources identified to achieve goals; periodic evaluation of their goals, objectives, and action plans; and their resume or CV. There were a few differences between the P1 and P2 CPD course. In addition to the above-mentioned assignments, the P2 students were also expected to create an e-portfolio program (MyCred, CORE Higher Education Group, West Warwick, RI) as a part of the first assignment and a personal SWOT (strengths, weakness, opportunities, and threats) analysis as a part of the second assignment. The goal of the e-portfolio was for the mentor to determine whether there were any major gaps in the student’s portfolio that could help with the professional development of that student. For example, if upon self-reflection, the student wanted to become a pharmacy manager, the mentor would evaluate the e-portfolio and action plan statements to ensure that the student was on track to accomplish this goal and encourage the student to serve in leadership roles in student organizations, attend conferences, and network with pharmacy managers. By identifying their strengths and weaknesses, the personal SWOT analysis also helped students with developing their goals for the year.

The CPD course delivered in the 2016-2017 academic year was evaluated in three different ways: skills evaluation, student evaluation of the course, and faculty evaluation of the course. The clinical faculty members at RUCOP were asked to provide a list of skills that all graduating pharmacists should possesses. Most of the clinical faculty members responded, and 26 skills were compiled. Based on these skills, a survey instrument was developed and administered to the students. Students were asked to self-reflect on their perceived importance of each skill and their capability in each skill. This exercise was intended to assist students with their goal development. For example, if a student perceived a skill as important but lacked confidence in that skill, that particular skill would be included in their goal setting for CPD. The 26 skills consisted of themes such as oral and written communication, demonstration of skills to colleagues and patients, team dynamics, leadership, time management, professionalism, clinical problem solving, and patient and healthcare provider education. Each skill was rated in two different ways and at two different points of time. The first rating was concerned with students’ perspective on the importance of these skills to the successful completion of the PharmD program. A 7-point rating scale was used on which 1=not important at all to 7=very important. The second rating was concerned with how well students currently performed each skill. For this rating, a 7-point scale was used on which 1=not well and 7=very well. During the CPD orientation in 2016-2017, the skills survey instrument was administered using the Qualtrics online system to both P1 and P2 students. At the end of the academic year, the skill survey instrument was again administered to students to evaluate any changes or improvements they had made. Self-reported change in skills over the year was measured.

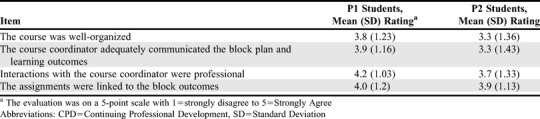

Another way in which the course was assessed was through student evaluations. The 2016-2017 end of year course evaluations from both P1 (n=95) and P2 (n=102) were collected. The course evaluation had four questions specific to the CPD course that assessed course organization, communication from the course coordinator about the block plan and learning outcomes, professionalism in the interaction between the students and course co-coordinator, and how well the portfolio assignments were linked to the block outcomes.

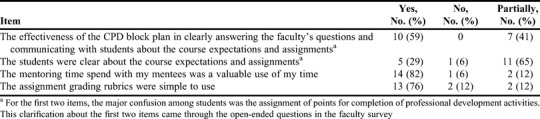

The third way the course was assessed was through faculty evaluations. At the end of the 2016-2017 academic year, faculty members (n=18) were asked to evaluate the course based on four items: effectiveness of the CPD block plan, meeting expectations of the students about the course and assignments, value of the mentoring time, and utility of the assignment grading rubrics.

RESULTS

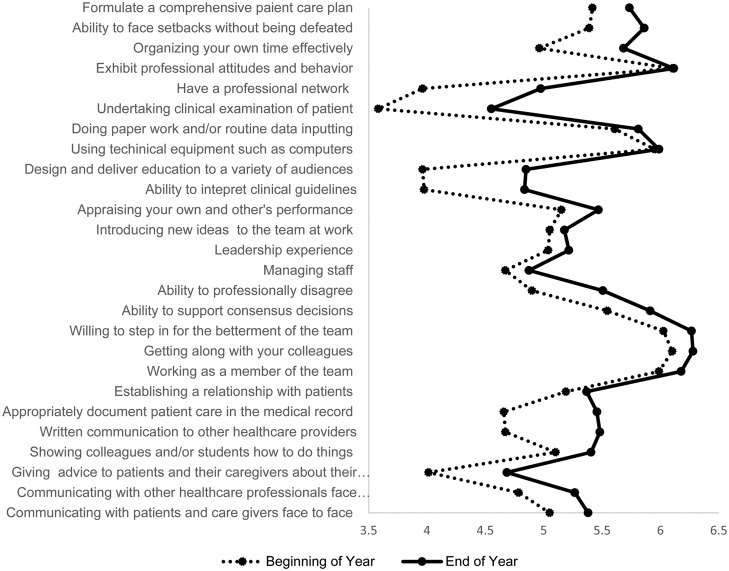

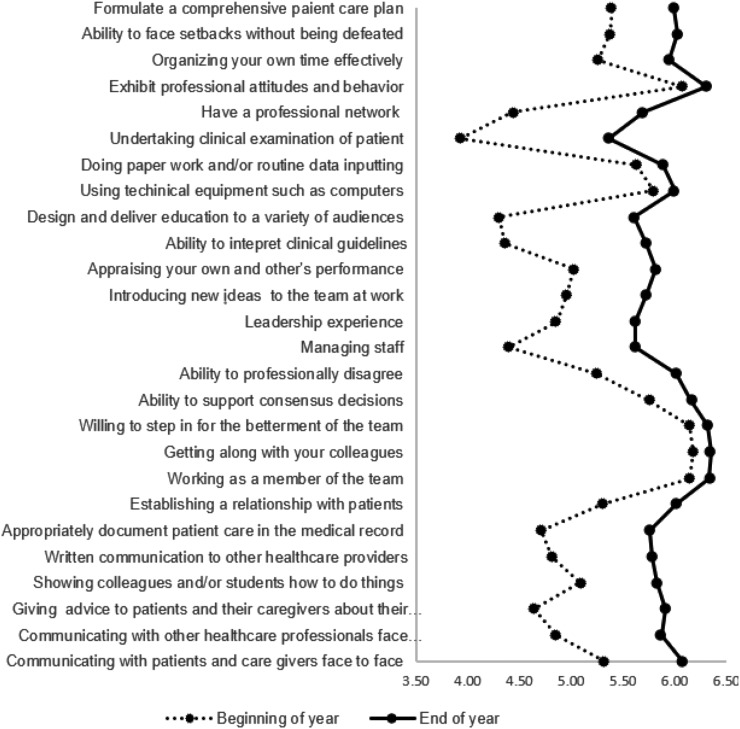

Seventy-nine P1 students (83% response rate) and 69 P2 students (68% response rate) completed the survey at both the beginning and end of the year. The results of the skill assessment are reported in Figures 3 and 4. The perceived ability of the students in performing most of these skills improved over the year. For P1 students, the capabilities on all the skills except “exhibiting professional attitudes” and “using technical equipment, such as computers,” improved over the year. The skills that students scored the lowest at the beginning of the year were clinical skills, such as undertaking a clinical examination, designing and deliberating education to a variety of audiences, interpreting clinical guidelines, and giving advice to patients and caregivers. The skills that improved the most were undertaking a clinical examination and having a professional network. For P2 students, the capabilities on all skills improved, and the maximum improvement was seen in undertaking a clinical examination, having a professional network, designing and delivering education to patients, managing staff, and advising patients and caregivers about the condition. There can always be an argument that the improvement in skills is not because of the CPD course. We accept that as a limitation. However, the survey served as a self-reflection exercise for the students to include that skill as a part of their goal development. Students having the awareness to know their weaknesses earlier may help them plan on how to overcome it earlier and be more successful.

Figure 3.

P1 Students’ Perceived Capabilities of Performing the Various Skills Related to a Practicing Pharmacist Between the Beginning and End of the Year

A 7-point scale was used on which 1=not well and 7=very well, to determine how well the P1 students performed on each of these skills at the beginning and end of the academic year. The y-axis demonstrates the 26 skills on which the students were measured on their perceived capability of performing and the x-axis shows the mean scores of their capabilities. Each data point shows the mean score for that particular skill, the point on the dotted line for the beginning of the year and the point on the solid line for the end of that year. When the solid line is on the right side, it shows an increase in the perceived capability over the year. Additionally, when the distance between the dotted and solid line increases, it shows that the change was large. The data points toward the y-axis (eg, undertaking clinical examination of the patient) show that these skills had the lowest perceived capability among students.

Figure 4.

P2 students’ Perceived Capabilities of Performing the Various Skills Related to a Practicing Pharmacist Between the Beginning and End of the Year

A 7-point scale was used on which 1= not well and 7=very well, to determine how well P2 students performed on each of these skills at the beginning and end of the academic year. The y-axis demonstrates the 26 skills on which the students were measured on their perceived capability of performing and the x-axis shows the mean scores of their capabilities. Each data point shows the mean score for that particular skill, the point on the dotted line for the beginning of the year and the point on the solid line for the end of that year. When the solid line is on the right side, it shows an increase in the perceived capability over the year. Additionally, when the distancebetween the dotted and solid line increases, it shows that the change was large. The data points toward the y-axis (eg, undertaking clinical examination of the patient) show that these skills had the lowest perceived capability among the students.

A tally of the professional development activities completed showed that students in the P1 class earned anywhere from 0 to 19 points, while students in the P2 class earned from 0 to 23 points over the year. The average points earned by P1 students for participating in professional development activities were 2.6 (SD=3.31) and those earned by P2 students were 3.4 (SD=4.4). Examples of professional development activities included attending national, state, and local conferences; presenting research results at a conference; taking part in interprofessional activities, such as morbidity and mortality conferences; participating in competitions, such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists’ clinical skills competition or the Academy of Managed Care’s Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee competition; attending health fairs and student organization community outreach activities; attending “lunch and learn” activities organized by student organizations or the college; and assisting with student interviews. The number of points that students earned varied for each activity. While some activities such as presenting a poster at a national conference could earn four points, attending three “lunch and learn” activities were needed to earn one point.

The feedback from the 18 faculty members involved in the CPD course is presented in Table 3, and the course evaluations from 154 students (response rate was 65% for P1 and 88% for P2) are presented in Table 4. The response rate to the faculty survey was 100%. While 59% of faculty members considered the CPD course to be very valuable for pharmacy students, the remaining 41% considered it to be all right. This was an increase from 36% in the previous year who considered this course to be valuable and 50% who considered it to be all right. When asked about difficulties encountered in meeting with the mentees, the major barrier was scheduling, especially for clinical faculty members who were not often on campus. Other barriers included students waiting until the last minute to schedule appointments, and (though infrequently) students not keeping appointments. In 2016-2017, 42% of faculty members met with their mentees at least two times during the year, while 53% met with them three to five times, and one faculty member met with students more than five times. When asked how much time they had spent grading each assignment, 71% answered one to four hours, 12% answered five to 10 hours, and 18% answered more than 10 hours.

Table 3.

Faculty Evaluations of a Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Course for PharmD Students at the End of the First Academic Year (2015-2016) in Which It Was Implemented (N=17)

Table 4.

Student Evaluation of the CPD Course for 2016-2017

DISCUSSION

We describe a continuous professional development course in a didactic curriculum, and the challenges faced and strategies adopted in its implementation. Because few schools with three-year PharmD programs have a CPD model as comprehensive as this, creating such a model had its own challenges. One of the major reasons for the successful implementation of this program was the support received from the school’s dean and upper administration. This support included the dean emphasizing the importance of CPD for student development by announcing it in faculty meetings and through email, serving as a mentor himself, adding mentoring responsibilities in the Memorandum of Understanding for the clinical faulty, and allocating time for faculty training in CPD at the beginning of the year and at the faculty retreat. As reflected in Table 1, some faculty members had reservations about this course. With busy schedules and workload, integrating a course that would require them to mentor 10 to 12 students throughout the year was not appealing to the faculty members. However, once the realization set in that this course was permanent, opposition faded and faculty members became more interested in providing feedback and recommendations to improve the course. This was evident from the 100% response rate to the faculty surveys and the valuable comments provided. The course coordinator worked with the faculty members to ensure their voices were heard and their feedback was taken into consideration.

The second important factor in the successful implementation of this course was the commitment from faculty members who served as mentors. Feedback about the course and suggestions to improve the course are collected from the faculty members each year and actions are taken by the course coordinators based on their feedback and suggestions. A major barrier raised by the faculty when the course was initially implemented was the lack of understanding about the expectations from the course and the assignments. This was overcome by revising and streamlining the block plan, mapping the course outcomes to each assignment, and providing mandatory training for faculty members about the CPD course and the block plan. They also had access to the CPD orientation material provided to the students. Efforts were taken to ensure the consistency in course expectations coming from the course coordinator and each faculty mentor. As recommended by faculty members, the grading rubric was simplified and grading of the students’ portfolios was limited to two times a year. Initially, the faculty members were given five to six students from P1 and P2 years which required faculty members to grade four assignments and be familiar with two block plans and the assignment due dates. Now, each faculty member is paired with 10 to 12 students from one class and they keep them throughout the two years of the program. This change resulted in reducing the workload as well as improving the mentor-mentee relationships. All the changes resulted in improved satisfaction with the course as evident from responses on faculty surveys and the discussions about the CPD program during the faculty retreat.

The third significant factor in implementing this program was the commitment of the students. Change is always difficult, and the students who enrolled the year the program was implemented showed more resistance. However, over the years, with the improved course block plan, errors remedied, and faculty committed, students have accepted the course as another requirement for the completion of the PharmD program. However, based on feedback from students, several changes have been made to the course. The most important changes were the class time spent on CPD and emphasizing the importance of CPD. Initially, the CPD program was presented in five classes throughout the year, with separate faculty members handling different topics. To some extent, this resulted in lack of continuity and inconsistency in course expectations. Now there is only one classroom lecture on CPD, and it is delivered by the course coordinator. The major advantage with this change is the consistency in the message regarding course expectations and emphasis on the significance of CPD and how this can be linked to students’ CV development. Additionally, emphasis is made on the mentor-mentee relationship and how each relationship varies based on the needs of the student and the individuality of the mentor. This has reduced student criticism about the subjective nature of grading by faculty mentors. Additionally, faculty mentors were reminded to keep grading variability in mind and to confirm their assessment of a student with the criteria in the grading rubric before issuing a grade. Another major change was switching e-portfolio vendors. Though the logistics took some time, the e-portfolio from the new vendor seems was acceptable.

Awarding points for attending professional development activities highlighted the importance of students becoming involved in the pharmacy community while in school. As can be seen from the results, the points earned by P2 students were much higher than those earned by P1 students, which shows involvement in the professional development activities, recording those activities, and taking credit for those activities in addition to increasing involvement with these activities by the time students are in P2 year. These professional activities can lead to networking, educational, and advocacy opportunities and contribute to other aspects of students’ professional development. Awarding points was also an incentive for students to document their professional development activities. As a final incentive, students had to participate in activities to earn honors for the course.

The CPD program is now in its fourth year, and despite the initial logistic issues and barriers, we are pleased with the progress we have made. Every class cohort is different as is every mentor-mentee relationship. However, with a strong curriculum plan and committed faculty and administration, the RUCOP CPD program is achieving the intended goals.

CONCLUSION

The Roseman University College of Pharmacy successfully implemented a continuing professional development program as a part of their didactic curriculum. Based upon faculty and student evaluations, this is a beneficial course to prepare students to be professionals with a commitment to lifelong learning. With the changing roles of pharmacists, CPD is an important avenue by which pharmacists can maintain their competencies in areas relevant to their respective professional responsibilities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. 2010. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/12704. Accessed November 23, 2017. [DOI]

- 2.Schindel TJ, Kehrer JP, Yuksel N, et al. University-based continuing education for pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ . 2012;76(2):Article 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Continuing Professional Development (CPD). https://www.acpe-accredit.org/continuing-professional-development/. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 5.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans J, Hamilton R, Dominelli A, et al. Introduction of continuing professional development to the pharmacy curriculum [abstract]. 108th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Orlando, FL, July 14-17, 2007. Am J Pharm Educ . 2007;71(3):Article 60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tofade T, Franklin B, Noell B, et al. Evaluation of a continuing professional development program for first year student pharmacists undergoing an introductory pharmacy practice experience. Inov Pharm. 2011;2(2):Article 40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janke KK, Tofade T. Making a curricular commitment to continuing professional development in doctor of pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(8):Article 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brocta R, Abu-baker A, Budukh P, et al. A continuous professional development process for first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(2):Article 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobson EH, Johnston PE, Spinelli AJ. Staging a reflective capstone course to transition PharmD graduates to professional life. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(1):Article 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rees JA, Cantrill JA, Morris M, et al. Attitudes to reflective practice and continuing professional development. Int J Pharm Pract. 2003;11(S1): R34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallman A, Lindblad AK, Hall S, et al. A categorization scheme for assessing pharmacy students’ levels of reflection during internships. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janke KK. Continuing professional development: don’t miss the obvious. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2):Article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]