Abstract

Patient: Female, 59

Final Diagnosis: Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura

Symptoms: Dyspnea • right back pain

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Thoracoscopic resection

Specialty: Pulmonology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

The incidence of solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP) is less than 5% of all pleural tumors. It is important to determine whether the tumor is benign or malignant in deciding on treatment and estimating prognosis, but this can sometimes be difficult.

Case Report:

A 59-year-old woman with no prior medical history presented with a 4-month history of right back pain and dyspnea. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a giant oval mass with inhomogeneous intensities, and bloody pleural effusion in the right thoracic cavity, proved to be solitary fibrous tumor of pleura (SFTP) under the complete thoracoscopic resection. The resected tumor seemed to have several malignant features, including large size of tumor, inhomogeneous intensities, and pleural effusion due to intratumor hemorrhage; however, Ki-67 (MIB-I) proliferation index was less than 1%, with no recurrence seen within 2 year after symptom onset.

Conclusions:

We managed a case of SFTP presenting both malignant and benign features. In patients with SFTP, multi-disciplinary discussion among the clinician, radiologist, and pathologist was considered to be needed for estimating disease prognosis.

MeSH Keywords: Pleural Effusion; Prognosis; Solitary Fibrous Tumor, Pleural

Background

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is rare mesenchymal tumor that typically originates from the pleura and pelvis. The incidence of SFT of the pleura (SFTP) is less than 5% of all pleural tumors [1,2]. The prognosis is relatively good, but up to 20% of cases are malignant [3]. It is important to determine whether the tumor is benign or malignant before deciding on treatment options and estimating prognosis, but this can sometimes be difficult. We managed a case of SFTP that showed a discrepancy in prognostic prediction between clinical and pathological findings.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with no prior medical history presented with a 4-month history of right back pain and dyspnea. A chest radiograph showed a mass lesion in the middle-to-lower right lung field (Figure 1), contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a giant oval mass (long diameter, 14 cm) in the right thoracic cavity, with inhomogeneous intensities (Figure 2A–2C), adhering to the Th4-5 level pleura via a pedicle (Figure 2D). A moderate right pleural effusion was also observed, which was bloody and exudative on thoracic puncture. On 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/CT, the mass showed mild FDG up-take (maximum standardized uptake value=3.1). Also, there were no increases in blood carcinoma-specific tumor markers, including carcino-embryonic antigen, cytokeratin-19 fragment, squamous cell carcinomas, neuron-specific enolase, progastrin-releasing peptide, soluble interleukin-2 receptor, human chorionic gonadotropin, and a-fetoprotein. From these findings, SFTP was clinically suspected and the mass and its pedicle were completely resected thoracoscopically (Figure 3A).

Figure 1.

A chest radiograph showing a mass lesion in the middle-to-lower right lung field.

Figure 2.

(A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography image of the chest (axial view) revealed a giant oval mass (long diameter, ≥10 cm) with inhomogeneous intensities and moderate pleural effusion in the right thoracic cavity. (B) Sagittal view of contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed the mass adhering to the Th4-5 level pleura via a pedicle (white arrow).

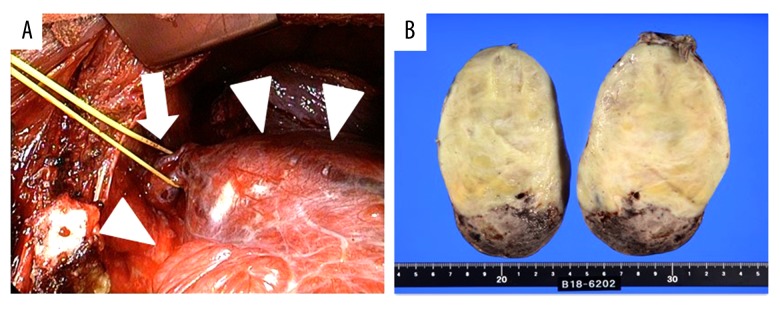

Figure 3.

(A) Intraoperative findings revealed a gigantic mass (arrow heads) adhering to the chest wall via a pedicle (arrow). The mass and its pedicle were completely resected thoracoscopically. (B) The macroscopic appearance was an oval, yellowish-white tumor with a diameter of 10 cm or more, and the tumor had hemorrhage and necrosis on the caudal side, consistent with the lesion showing inhomogeneous intensities in the chest CT.

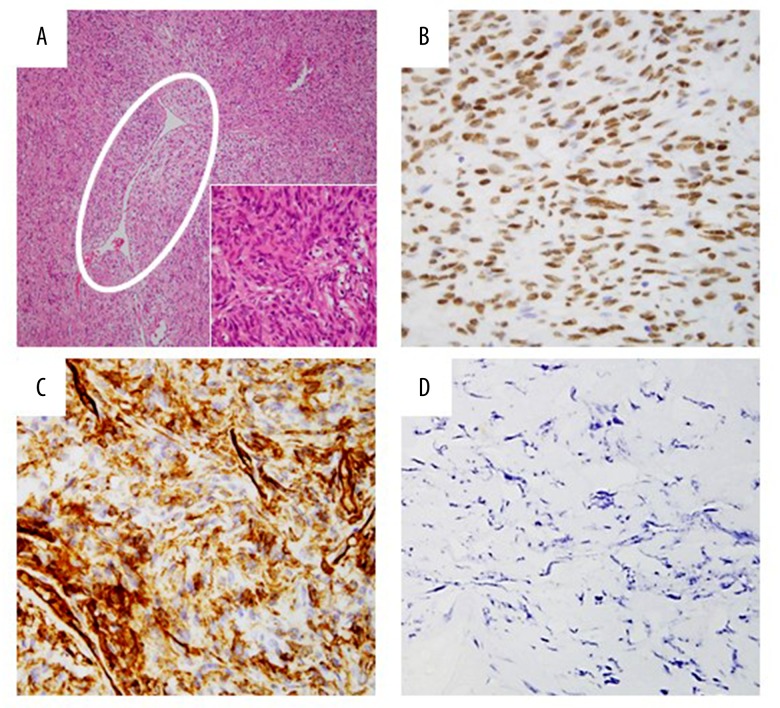

Despite the presence of bloody pleural effusion, no evidence of metastasis and pleural dissemination were found in intra-operative findings, and the pleural effusion had no evidence of malignancy. On the macroscopic examination of the resected tumor, intratumor hemorrhage and necrosis were observed (Figure 3B). Microscopically, irregular fascicles of spindle cells with positive results of CD34 and STAT6 for the diagnostic biomarkers of SFT and staghorn-like blood vessels were observed (Figure 4A–4C). Ki-67 (MIB-1) proliferation index for the detectable biomarker of malignant feature was less than 1% (Figure 4D). The histological diagnosis was SFTP with no recurrence observed for 2 years after symptom onset (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Histological specimen revealed irregular fascicles of spindled cells and staghorn-like blood vessel (white circle) with deposition of collagen (A). Immunohistochemical staining of tumor cells were positive for CD34 (B) and STAT6 (C). Spindle cells proliferation and STAT6-positive cells were not observed in the pedicle. Ki-67 (MIB-1) proliferation index was less than 1% (D).

Figure 5.

A chest radiograph 2 years after symptom onset showed no recurrence.

Discussion

SFTP is rare spindle cell tumor typically originated from the visceral pleura. Although its incidence is less than 5% of all pleural tumors, it has been increasingly recognized over the past few years [1,2]. Although the predominant onset age of SFTP is reported to be the sixth and seventh decades of life, it can also occur in any age group [4]. Many patients (about 50%) with SFTP are asymptomatic and tumors are often found incidentally on chest radiograph [5]. However, some patients may have cough, chest pain, and dyspnea related to the size of the lesions. Ten-year overall survival rates widely ranged from 66.9% to 97.5% [1,6]. Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for both benign and malignant SFTP.

Making the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant SFTP is usually problematic for predicting the disease prognosis. Although criteria for defining malignant SFTP have been discussed in previous reports [7–10], there have been no established biomarkers for distinguish malignancy from benign in patients with SFTP.

Originally, in a clinicopathological review of 223 localized fibrous tumor of pleura, England et al. defined tumor size ≥10 cm, tumor necrosis and hemorrhage, mitoses ≥4/10 high-power field, increased cellularity, and nuclear pleomorphism as the malignant features of SFTP [7]. Recently, in a radiographical review of 60 SFTP cases, You et al. reported that larger tumor size, inhomogeneous intensities, abundant intratumor blood vessels, and pleural effusions in the chest CT were more common in malignant SFTP [8]. The present case had several malignant features, including large size of tumor, intratumor hemorrhage, inhomogeneous intensities, and pleural effusion. However, in the pathological analysis of 78 SFTP cases, Diebold et al. reported that Ki-67 (MIB-1) proliferation index ≥10%, which was expressed in active phases of the cell cycle, including G1, S, G2, and mitosis, appear to have strong association with the degree of histopathological malignancy and are independent prognostic factors [9,10]. In the present case, the Ki-67 (MIB-1) proliferation index was less than 1%. Therefore, we thought the present case showed both malignant and benign features, and careful follow-up was necessary to detect the recurrence, although the patient was without recurrence for 2 years after onset. Furthermore, in patients with SFTP, multi-disciplinary discussion among the clinician, radiologist, and pathologist is important for prognostic prediction and follow-up for detecting recurrence, and occasionally it is helpful for Ki-67 (MIB-1) proliferation index to distinguish between malignant and benign tumors.

Conclusions

We managed a case of SFTP presenting both malignant features, including large size of tumor, intratumor hemorrhage, inhomogeneous intensities, and pleural effusion, and benign feature including low Ki-67 (MIB-1) proliferation index. In patients with SFTP, multi-disciplinary discussion among clinicians, radiologists, and pathologists was considered to be needed for deciding on treatment options and estimating disease prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Koki Maeda for pathological diagnosis of this case.

References:

- 1.Lococo F, Cesario A, Cardillo G, et al. Malignant solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: retrospective review of a multicenter series. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1698–706. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182653d64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu C, Ji Y, Shan F, Guo W, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: An analysis of 13 cases. World J Surg. 2008;32:1663–68. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9604-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sureka B, Thukral BB, Mittal MK, et al. Radiological review of pleural tumors. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2013;23:313–20. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.125577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briselli M, Mark EJ, Dickersin GR. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: eight new cases and review of 360 cases in the literature. Cancer. 1981;47:2678–89. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810601)47:11<2678::aid-cncr2820471126>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson LA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Cancer Control. 2006;13:264–69. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardillo G, Carbone L, Carleo F, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: Aan analysis of 110 patients treated in a single institution. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1632–37. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–58. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.You X, Sun X, Yang C, Fang Y. CT diagnosis and differentiation of benign and malignant varieties of solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e9058. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diebold M, Soltermann A, Hottinger S, et al. Prognostic value of MIB-1 proliferation index in solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura implemented in a new score – a multicenter study. Respir Res. 2017;18:210. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0693-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Y, Naito Z, Ishiwata T, et al. Basic FGF and Ki-67 proteins useful for immunohistological diagnostic evaluations in malignant solitary fibrous tumor. Pathol Int. 2003;53:284–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]