Abstract

Background

The small molecule inhibitor XAV939 could inhibit the proliferation and promote the apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. This study was conducted to identify the key circular RNAs (circRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) in XAV939-treated NSCLC cells.

Methods

After grouping, the NCL-H1299 cells in the treatment group were treated by 10 μM XAV939 for 12 h. RNA-sequencing was performed, and then the differentially expressed circRNAs (DE-circRNAs) were analyzed by the edgeR package. Using the clusterprofiler package, enrichment analysis for the hosting genes of the DE-circRNAs was performed. Using Cytoscape software, the miRNA-circRNA regulatory network was built for the disease-associated miRNAs and the DE-circRNAs. The DE-circRNAs that could translate into proteins were predicted using circBank database and IRESfinder tool. Finally, the transcription factor (TF)-circRNA regulatory network was built by Cytoscape software. In addition, A549 and HCC-827 cell treatment with XAV939 were used to verify the relative expression levels of key DE-circRNAs.

Results

There were 106 DE-circRNAs (including 61 upregulated circRNAs and 45 downregulated circRNAs) between treatment and control groups. Enrichment analysis for the hosting genes of the DE-circRNAs showed that ATF2 was enriched in the TNF signaling pathway. Disease association analysis indicated that 8 circRNAs (including circ_MDM2_000139, circ_ATF2_001418, circ_CDC25C_002079, and circ_BIRC6_001271) were correlated with NSCLC. In the miRNA-circRNA regulatory network, let-7 family members⟶circ_MDM2_000139, miR-16-5p/miR-134-5p⟶circ_ATF2_001418, miR-133b⟶circ_BIRC6_001271, and miR-221-3p/miR-222-3p⟶circ_CDC25C_002079 regulatory pairs were involved. A total of 47 DE-circRNAs could translate into proteins. Additionally, circ_MDM2_000139 was targeted by the TF POLR2A. The verification test showed that the relative expression levels of circ_MDM2_000139, circ_CDC25C_002079, circ_ATF2_001418, and circ_DICER1_000834 in A549 and HCC-827 cell treatment with XAV939 were downregulated comparing with the control.

Conclusions

Let-7 family members and POLR2A targeting circ_MDM2_000139, miR-16-5p/miR-134-5p targeting circ_ATF2_001418, miR-133b targeting circ_BIRC6_001271, and miR-221-3p/miR-222-3p targeting circ_CDC25C_002079 might be related to the mechanism in the treatment of NSCLC by XAV939.

1. Introduction

In lung cancers, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) are the two main types [1]. Lung cancer usually can result in shortness of breath, coughing, chest pains, and weight loss [2, 3]. In 2012, there were 1.8 million new cases of lung cancer and led to 1.6 million deaths globally [4]. Especially, NSCLC takes up 85% of all lung cancer cases, which are mainly induced by smoking [5]. As NSCLC progresses from stage I to stage IV, the five-year survival rate reduces from 47% to 1% [6]. Therefore, it is essential to study the treatment for NSCLC and related mechanism.

XAV939 is a tankyrase (TNKS) inhibitor and an indirect Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor that is often used to inhibit proliferation of NSCLC cells. Guo et al. reported that XAV939 could inhibit the viability of SCLC NCI–H446 cells by causing cell apoptosis through the Wnt signaling pathway [7]. Besides, XAV939 also repressed the proliferation and migration of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells through attenuating the Wnt signaling pathway [8]. Moreover, it is known that circular RNAs (circRNAs) are implicated in the development and progression of cancers [9]. CircRNA_100876 is tightly correlated with the oncogenesis of NSCLC, which may function as a promising prognostic marker and therapeutic target for the disease [10]. Circ_0014130 can serve as a candidate biomarker for NSCLC, and may play critical roles in the formation of the tumor [11]. Besides, plenty of reports have stated that the circRNAs usually be involved in the NSCLC by the interaction with miRNAs. CircRNA forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) acts as a tumor suppressor via sponging miR-155 in NSCLC, and thus expression restoration of circRNA FOXO3 can be a new therapeutic option for NSCLC [12]. CircRNA_100833 (also called circRNA fatty acid desaturases 2, circFADS2) promotes the progression of NSCLC through mediating miR-498 expression; therefore, circFADS2 can be utilized as a novel target for treating NSCLC [13]. However, the key circRNAs associated with the pathogenesis of NSCLC have not been entirely revealed.

Our preliminary experiments showed that XAV939 could significantly inhibit the proliferation and promote the apoptosis of NSCLC NCL-H1299 cells, and 10 μM is the appropriate XAV939 concentration for treating NCL-H1299 cells (data not shown). In this study, XAV939 (10 μM) was used to treat NCL-H1299 cells in the treatment group. After high throughput sequencing, the sequencing data were analyzed using various bioinformatics methods. This study might contribute to revealing the key circRNAs mediated by XAV939 in NCL-H1299 cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Source

The NSCLC NCL-H1299 cell line was obtained from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Six NCL-H1299 cell samples were randomly and evenly divided into the treatment group and control group. The cells in the treatment group were treated by XAV939 (10 μM) for 12 h. The cells in the control group were treated by equal volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Afterwards, the cells were harvested for the following sequencing.

2.2. Library Construction and RNA-Sequencing

Using the TRIzol reagent (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China), total RNA was extracted from the cells according to the manufacturer's instruction. Then, the quality and quantity of total RNA were detected using a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). Subsequently, cDNA library was constructed following the manufacturer's manual by a TruseqTM RNA Library Prep kit for Illumina® (cat no. E7530L; New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). Based on the 150 paired end method [14], sequencing was performed by the Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The sequencing data were deposited in Sequence Read Archives (SRA, https://http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) database under the accession number SRP136747.

2.3. Quality Control and Preprocessing of Sequencing Data

Quality control of the sequencing data was conducted using Trimmomatic tool [15]. Barcode sequences were removed, and the bases with continuous quality <10 at two ends of the reads were taken out. Subsequently, the reads that contained less than 80% bases with Q > 20 were filtered out, and the reads with length <50 nt were also wiped off. Based on TopHat2 software (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat) [16], clean reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38.p7 and GENCODE) [17]. In order to obtain back-spliced junctions reads, the reads that could not be compared to the reference genome in a linear way were compared in a nonlinear way using TopHat-fusion algorithm [18].

2.4. Identification and Annotation of CircRNAs

CircRNAs were identified using CIRCexplorer2 software [19], and the circRNAs with junctions read count > 2 were selected. Based on the locations of circRNAs in the genome and their relationships with genes, the selected circRNAs were annotated. Firstly, the circRNAs were classified according to their locations. Secondly, the circRNAs were conducted with functional annotation based on the circRNA-hosting genes. The RefSeq gene annotation files downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC, http://genome.ucsc.edu/) database [20] were used as references for annotating. Finally, the circRNAs were named combined with the names of their hosting genes.

2.5. Identification of the Differentially Expressed CircRNAs (DE-CircRNAs) and Enrichment Analysis

The expression of the circRNAs was estimated based on the number of back-spliced reads. Using the edgeR package (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html) in R [21], the DE-circRNAs between treatment and control groups were screened. The |log2 fold change (FC)| > 0.585 and p value <0.05 were defined as the thresholds. The expression of circRNA was required to be higher than 0 in at least 2 samples, and the ineligible circRNAs were filtered out.

Using the clusterprofiler package (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html) in R [22], the hosting genes of the DE-circRNAs were studied with Gene Ontology (GO, including biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC) categories) [23] and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) [24] enrichment analyses. The significant threshold was set at p value <0.05.

2.6. MiRNA Sponge Analysis and Disease Association Analysis

Previous studies have found that there are multiple target sites of miRNAs in some circRNAs sequences, and thus circRNAs can bind with miRNAs to play certain regulatory roles in vivo [25, 26]. Using miRanda tool [27], miRNA-circRNA pairs were predicted for the DE-circRNAs.

Based on DisGenet (http://www.disgenet.org) [28] and miRWalk (http://mirwalk.uni-hd.de/) [29] databases, the genes or miRNAs correlated with NSCLC were searched. If the hosting genes of DE-circRNAs were related to NSCLC, the DE-circRNAs were deemed to be associated with the disease. For the disease-associated miRNAs and the DE-circRNAs, the miRNA-circRNA regulatory network was built using Cytoscape software (http://www.cytoscape.org) [30].

2.7. Prediction of the CircRNAs with the Ability to Translate into Proteins

The corresponding data of the DE-circRNAs were obtained from circBank (http://www.circbank.cn/) and circBase [31] databases. The DE-circRNAs with protein-encoding ability (coding_prob > 0.364) were selected from circBank database. Besides, the IRESfinder tool [32] was used to predict whether there were internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) in the DE-circRNAs. The circRNAs with both protein-encoding ability and IRESs were considered to be with the ability to translate into proteins.

2.8. Construction of Transcription Factor (TF)-CircRNA Regulatory Network

The TRCirc database [33] (http://www.licpathway.net/TRCirc/view/index) integrates the chip-sequencing data, RNA-sequencing data, and 450k array data in ENCODE database and combines with human circRNA information in circBase database for the analysis of circRNA transcriptional regulation. TFs were predicted for the DE-circRNAs using TRCirc database [33], and then TF-circRNA regulatory network was constructed using Cytoscape software [30].

2.9. Validation of Key DE-circRNAs in A549 and HCC-827 Cell Treatment with XAV939

In order to observe the effect of XAV939 on the expressions of key DE-circRNAs, A549 and HCC-827 cells were used. A549 and HCC-827 cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). Cells in the logarithmic growth phase of the experimental group were treated with 10 μM XAV939, and the control group was supplemented with an equal volume of DMSO. Then, the total RNA was extracted by the TRIzol reagent (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). Finally, the relative expression levels of key DE-circRNAs were detected by the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The primer information is shown in the Supplementary .

3. Results

3.1. Data Preprocessing, Identification, and Annotation of CircRNAs

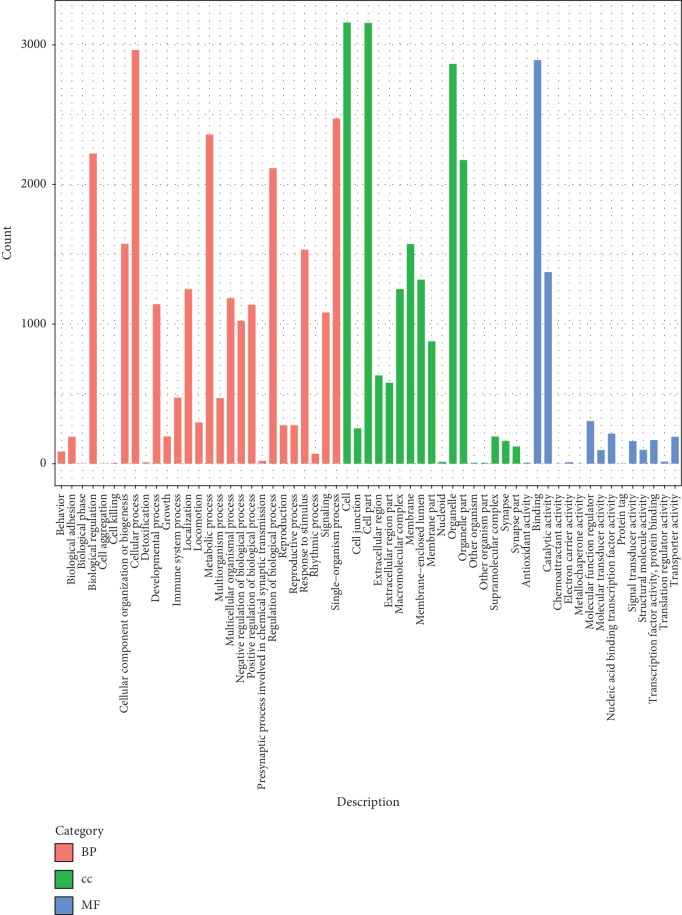

The results of quality control and sequence alignment separately were listed in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 8914 circRNAs corresponding to 3542 hosting genes were identified. After annotation of the circRNAs, the GO functional terms enriched for the hosting genes of the circRNAs are shown in Figure 1, such as biological regulation, cellular progress, chemoattractant activity, and so on.

Table 1.

The results of quality control for the sequencing data.

| Sample | Raw reads | Clean reads | Effective rate (%) | Error rate (%) | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k3 | 55388409 | 54435729 | 98.28 | 0.01 | 98.17 | 95.44 | 46.97 |

| k2 | 52553686 | 51681295 | 98.34 | 0.01 | 97.93 | 94.92 | 47.2 |

| k1 | 52146382 | 51484123 | 98.73 | 0.01 | 98.18 | 95.44 | 47.73 |

| s3 | 54313514 | 53504243 | 98.51 | 0.01 | 96.92 | 92.81 | 47.05 |

| s2 | 49367345 | 48641646 | 98.53 | 0.01 | 98.19 | 95.47 | 47.52 |

| s1 | 53737400 | 52909845 | 98.46 | 0.01 | 97.76 | 94.55 | 47.31 |

Note. s1, s2, and s3 represent the samples in the treatment group. k1, k2, and k3 represent the samples in the control group. Sample, the name of samples; raw reads, the number of raw reads; clean reads, the number of clean reads; error rate, the average base sequencing error rate; Q20, the percentage of the bases with Phred value > 20; Q30, the percentage of the bases with Phred value > 30; GC content, the percentage of G/C bases.

Table 2.

The results of sequence alignment.

| Reads | Mapping | k3 | k2 | k1 | s3 | s2 | s1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left reads | Input | 54435729 | 51681295 | 51484123 | 53504243 | 48641646 | 52909845 |

| Mapped reads | 43706641 | 41399669 | 40805316 | 42960786 | 38202327 | 41965536 | |

| Mapped rate (%) | 80.29 | 80.11 | 79.26 | 80.29 | 78.54 | 79.32 | |

| Uniquely mapped | 40483797 | 38479400 | 37712691 | 40029424 | 35183009 | 38751263 | |

| Uniquely mapped rate (%) | 74.37 | 74.46 | 73.25 | 74.82 | 72.33 | 73.24 | |

| Right reads | Input | 54435729 | 51681295 | 51484123 | 53504243 | 48641646 | 52909845 |

| Mapped reads | 41882371 | 39205669 | 39063079 | 40162292 | 36529153 | 39526360 | |

| Mapped rate (%) | 76.94 | 75.86 | 75.87 | 75.06 | 75.10 | 74.71 | |

| Uniquely mapped | 38760420 | 36422877 | 36072263 | 37394997 | 33623734 | 36501173 | |

| Uniquely mapped rate (%) | 71.20 | 70.48 | 70.06 | 69.89 | 69.13 | 68.99 | |

| Overall read | Mapped rate (%) | 78.60 | 72.60 | 77.60 | 77.70 | 76.80 | 77.00 |

Note. s1, s2, and s3 represent the samples in the treatment group. k1, k2, and k3 represent the samples in the control group. Left/right reads, sequences at the two ends; input, the total number of sequences; mapped reads, the number of the reads mapped to the genome; mapping rate, the ratio of the reads mapped to the genome; unique mapped, the number of the reads mapped to a unique position in the genome; unique rate, the ratio of the reads mapped to a unique position in the genome.

Figure 1.

The functional terms enriched for the hosting genes of the identified circular RNAs (circRNAs). BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; and MF, molecular function.

3.2. Differential Expression Analysis and Enrichment Analysis

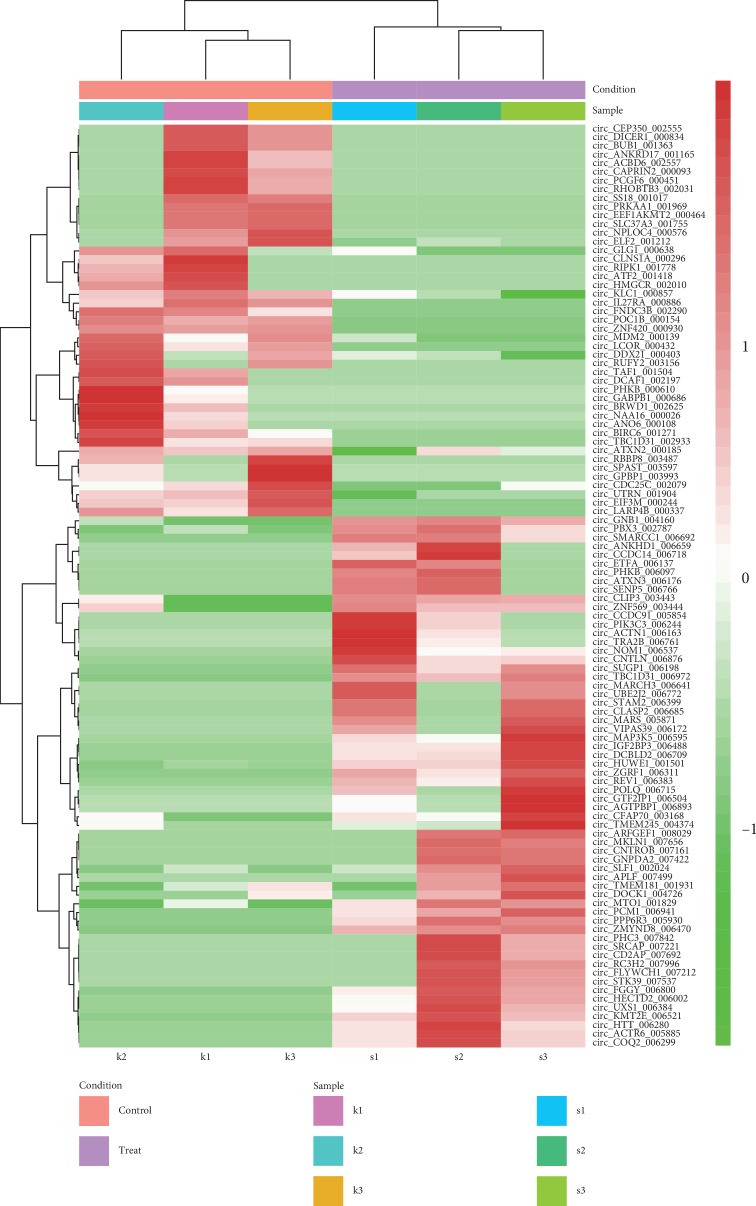

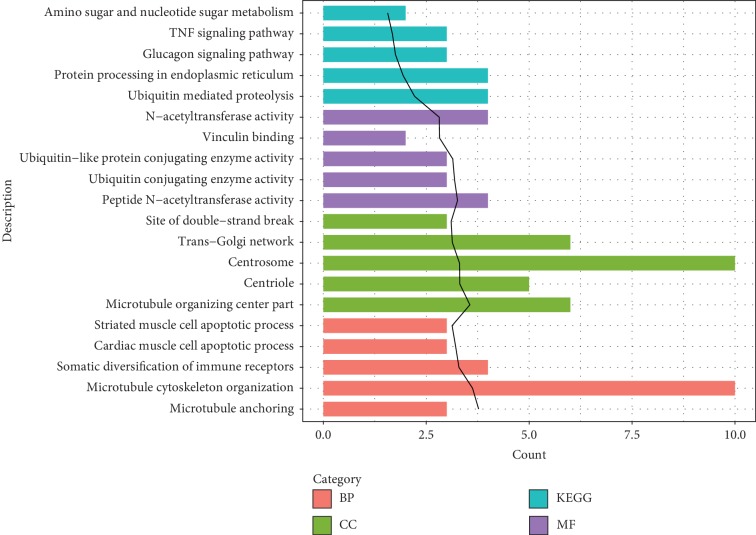

There were 106 DE-circRNAs between treatment and control groups, including 61 upregulated circRNAs and 45 downregulated circRNAs (Table 3). The clustering heatmap of the DE-circRNAs is presented in Figure 2. The samples of control and treatment groups were significantly separated by the DE-circRNAs. For the hosting genes of the DE-circRNAs, 204 BP terms (such as microtubule cytoskeleton organization), 27 CC terms (such as centrosome), 40 MF terms (such as N-acetyltransferase activity), and 9 KEGG pathways (such as the TNF signaling pathway, which involved activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2)) were enriched (Figure 3).

Table 3.

The most significant differentially expressed circular RNAs (circRNAs) (top 10 listed).

| CircRNA_name | Chrome | Exon count | Gene name | logFC | logCPM | LR | P value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circ_POC1B_000154 | chr12 | 6 | POC1B | –5.905057 | 8.894108 | 13.44331 | 0.000246 | 0.277026 |

| circ_RUFY2_003156 | chr10 | 4 | RUFY2 | –5.727558 | 8.778988 | 11.1986 | 0.000819 | 0.691708 |

| circ_HMGCR_002010 | chr5 | 3 | HMGCR | –5.434035 | 8.602139 | 8.488467 | 0.003574 | 0.711366 |

| circ_NPLOC4_000576 | chr17 | 3 | NPLOC4 | –5.243566 | 8.494641 | 7.161364 | 0.007449 | 0.711366 |

| circ_CAPRIN2_000093 | chr12 | 5 | CAPRIN2 | –5.228417 | 8.487116 | 7.073269 | 0.007824 | 0.711366 |

| circ_ZMYND8_006470 | chr20 | 4 | ZMYND8 | 5.2603368 | 8.50343 | 7.25106 | 0.007086 | 0.711366 |

| circ_SENP5_006766 | chr3 | 1 | SENP5 | 5.3402468 | 8.54897 | 7.790759 | 0.005251 | 0.711366 |

| circ_ARFGEF1_008029 | chr8 | 3 | ARFGEF1 | 5.6240365 | 8.715481 | 10.05927 | 0.001516 | 0.711366 |

| circ_RC3H2_007996 | chr9 | 7 | RC3H2 | 5.9666606 | 8.935713 | 14.32273 | 0.000154 | 0.260251 |

| circ_DCBLD2_006709 | chr3 | 5 | DCBLD2 | 7.1049669 | 9.787842 | 39.81423 | 2.79E-10 | 9.44E-07 |

Note. FC, fold change; CPM, counts per million; LR, likelihood ratio; FDR, false discovery rate.

Figure 2.

The clustering heatmap of the differentially expressed circular RNAs (circRNAs). s1, s2, and s3 represent the samples in the treatment group. k1, k2, and k3 represent the samples in the control group.

Figure 3.

The functional terms and pathways enriched for the hosting genes of the differentially expressed circular RNAs (circRNAs) (top 5 listed). BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; and KEGG, Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. The black trend line represents -log10 (p value).

3.3. miRNA Sponge Analysis and Disease Association Analysis

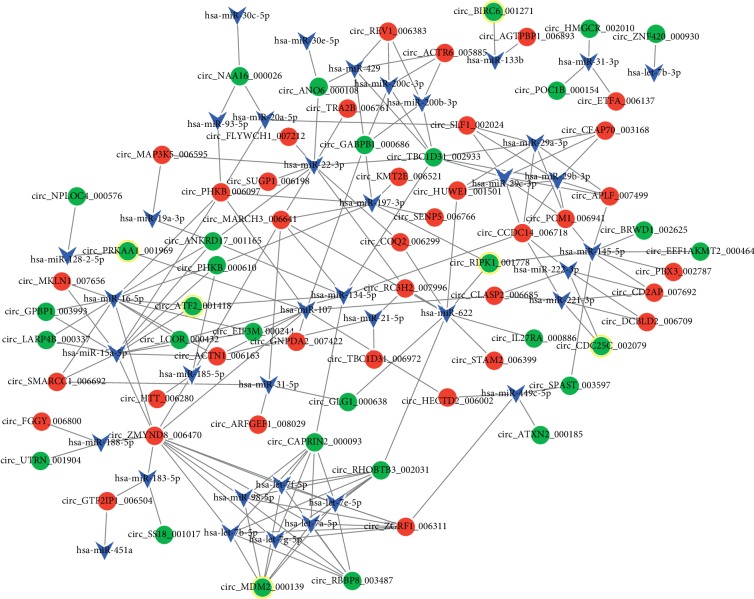

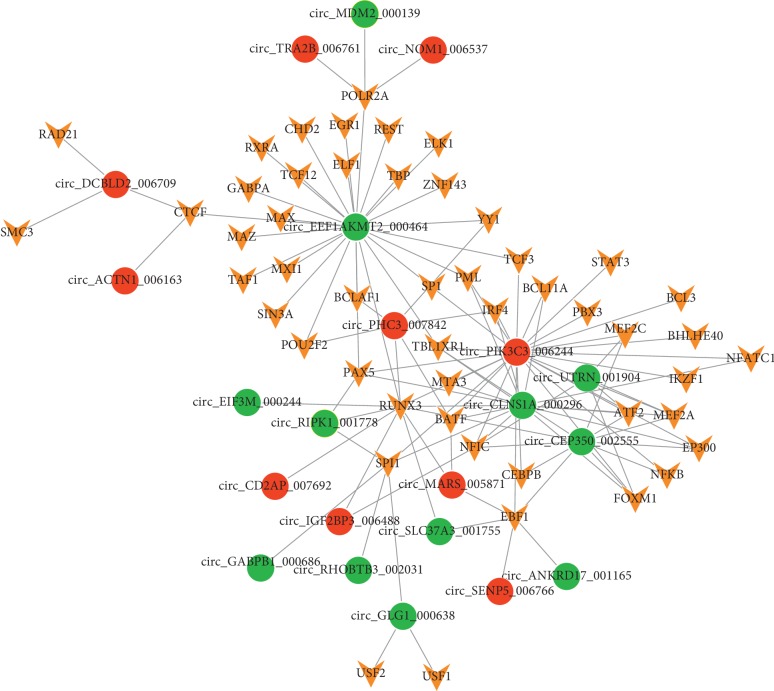

After miRNA-circRNA pairs were predicted for the DE-circRNAs, the top 10 miRNAs targeting more circRNAs were selected and listed in Table 4. Through disease association analysis, 8 circRNAs (including circ_MDM2_000139, corresponding to hosting gene MDM2 (murine double minute 2); circ_ATF2_001418, corresponding to hosting gene ATF2; circ_CDC25C_002079, corresponding to hosting gene CDC25C (cell division cycle 25C); and circ_BIRC6_001271, corresponding to hosting gene BIRC6 (baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat-containing 6)) were found to be related to the disease (Table 5). Finally, the miRNA-circRNA regulatory network was constructed, which had 106 nodes (including 38 miRNAs and 64 circRNAs) and 194 regulatory pairs (including let-7 family members⟶circ_MDM2_000139, miR-16-5p/miR-134-5p⟶circ_ATF2_001418, miR-133b⟶circ_BIRC6_001271, hsa-miR-197-3p circ_RIPK1_001778, hsa-miR-128-2-5p circ_PRKAA1_001969, and miR-221-3p/miR-222-3p⟶circ_CDC25C_002079) (Figure 4).

Table 4.

The top 10 miRNAs targeting more circular RNAs (circRNAs).

| MiRNA | Frequency |

|---|---|

| hsa-miR-4659b-3p | 32 |

| hsa-miR-4778-3p | 32 |

| hsa-miR-4659a-3p | 30 |

| hsa-miR-4691-5p | 27 |

| hsa-miR-6792-3p | 27 |

| hsa-miR-3059-5p | 24 |

| hsa-miR-6875-3p | 24 |

| hsa-miR-103a-1-5p | 23 |

| hsa-miR-103a-2-5p | 22 |

| hsa-miR-6881-3p | 21 |

Table 5.

The circular RNAs (circRNAs) correlated with non-small cell lung cancer.

| CircRNA_name | Gene symbol | Disease name | Score | No. of Pmids | No. of Snps | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circ_MDM2_000139 | MDM2 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.2085165 | 32 | 2 | BEFREE; CTD_human |

| circ_ATF2_001418 | ATF2 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0005495 | 2 | 0 | BEFREE |

| circ_DICER1_000834 | DICER1 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0008242 | 3 | 0 | BEFREE |

| circ_PRKAA1_001969 | PRKAA1 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0002747 | 1 | 0 | BEFREE |

| circ_BIRC6_001271 | BIRC6 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0002747 | 1 | 0 | BEFREE |

| circ_BUB1_001363 | BUB1 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0002747 | 1 | 0 | BEFREE |

| circ_RIPK1_001778 | RIPK1 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0005495 | 2 | 0 | BEFREE |

| irc_CDC25C_002079 | CDC25C | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | 0.0002747 | 1 | 0 | BEFREE |

Figure 4.

The miRNA-circular RNA (circRNA) regulatory network. Blue triangles, red circles, and green circles represent miRNAs, upregulated circRNAs, and downregulated circRNAs, respectively. The circles with yellow ring represent disease-associated circRNAs.

3.4. Prediction of the CircRNAs with the Ability to Translate into Proteins

The DE-circRNAs were mapped to circBank and circBase databases, and three novel circRNAs (including circ_ATF2_001418, circ_FLYWCH1_007212, and circ_GTF2IP1_006504) were not found in the two databases. Among the 65 DE-circRNAs with protein-encoding ability, there were 47 DE-circRNAs which had IRESs. Therefore, the 47 DE-circRNAs were taken as circRNAs that could translate into proteins.

3.5. Construction of TF-CircRNA Regulatory Network

After TFs were predicted for the DE-circRNAs, the TF-circRNA regulatory network was built (Figure 5). In the TF-circRNA regulatory network, there were 72 nodes (including 22 circRNAs and 50 TFs) and 115 edges. Especially, circ_MDM2_000139, which was correlated with the disease, was targeted by RNA polymerase II (POLR2A) in the TF-circRNA regulatory network.

Figure 5.

The transcription factor (TF)-circRNA regulatory network. Orange inverted triangles represent TFs. Red circles and green circles represent upregulated circRNAs and downregulated circRNAs, respectively. The circles with yellow ring represent the disease-associated circRNAs.

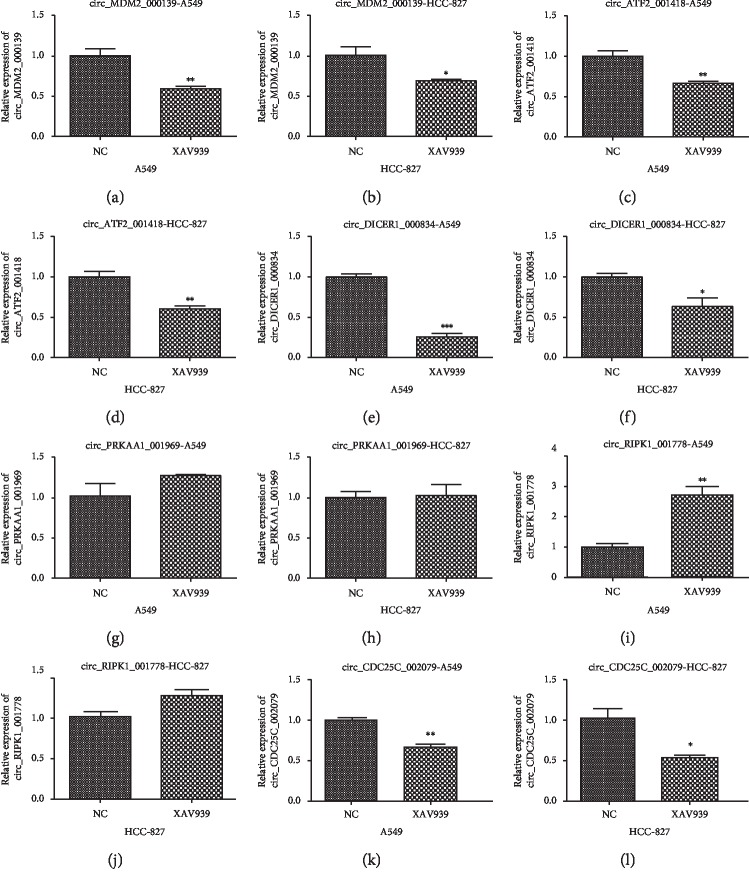

The expressed levels of key DE-circRNAs in A549 and HCC-827 cells are treated by XAV939

In order to validate the effect of XAV939 on other NSCLC cells, the relative levels of key DE-cirRNAs such as circ_MD-M2_000139, circ_ATF2_001418, circ_DICER1_000834, circ_PRKAA1_001969, circ_RIPK1_001778, and circ_CDC25C_002079 were further studied in A549 and HCC-827 cells. As shown in Figure 6, comparing with the NC group, the relative expression levels of circ_MDM2_000139, circ_CDC25C_002079, circ_ATF2_001418, and circ_DICER1_000834 in A549 and HCC-827 cell treatment with XAV939 were downregulated (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). There were no differences in the circ_PRKAA1_001969 levels between the control and XAV939 group. In addition, after treatment with XAV939, the circ_RIPK1_001778 levels were upregulated in the A549 cells, and no obvious change was found in HCC-827 cells.

Figure 6.

The relative expressions of key DE-circRNAs in the A549 and HCC-827 cells. NC represents the control cells. XAV939 represents the A549 and HCC-827 cells treated by 10 μM XAV939. ∗P < 0.05 indicates a significant difference compared with that of the NC group; ∗∗P < 0.01 indicates a very significant difference compared with that of the NC group; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

4. Discussion

In this study, 106 DE-circRNAs (including 61 upregulated circRNAs and 45 downregulated circRNAs) were screened between the treatment and control groups. Disease association analysis showed that 8 circRNAs (including circ_MDM2_000139, circ_ATF2_001418, circ_CDC25C_002079, and circ_BIRC6_001271) were correlated with NSCLC. Besides, let-7 family members⟶circ_MDM2_000139, miR-16-5p/miR-134-5p⟶circ_ATF2_001418, miR-133b⟶circ_BIRC6_001271, and miR-221-3p/miR-222-3p⟶circ_CDC25C_002079 regulatory pairs were involved in the miRNA-circRNA regulatory network. Furthermore, 47 DE-circRNAs were taken as circRNAs that could translate into proteins. In addition, circ_MDM2_000139 was found to be targeted by POLR2A in the TF-circRNA regulatory network. The results of validation experiments showed that circ_MDM2_000139, circ_CDC25C_002079, circ_ATF2_001418, and circ_DICER1_000834 were also downregulated in the A549 and HCC-827 cells after treatment with the XAV939, which were consistent with the sequencing results.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) acts as a critical inflammatory factor that links inflammation and tumor, which is also correlated with angiogenesis, proliferation, invasion, and migration in human cancers [34]. Via TNF-α/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways, sotetsuflavone suppresses the migration and invasion of NSCLC cells and may be effective in treating the tumor [35]. Through targeting ATF2, tumor suppressor miR-204 can inhibit cell proliferation and migration, and promote G1 arrest and cell apoptosis in NSCLC [36]. Elevated miR-16 is an independent factor that predicts unfavorable overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS), and thus miR-16 expression may be taken as a prognostic indicator in NSCLC [37]. Via mediating oncogenic cyclin D1 (CCND1), miR-134 represses proliferation, invasion, and migration and accelerates apoptosis of NSCLC cells [38, 39]. ATF2 was enriched in the TNF signaling pathway, suggesting that miR-16-5p/miR-134-5p targeting circ_ATF2_001418 might act in the mechanisms of NSCLC through the TNF signaling pathway. We concluded that the TNF signaling pathway might be another potential target of XAV939.

MDM2 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) expressions are related to the formation and migration of lung cancer; therefore, they can serve as the markers for the treatment and prognosis of the disease [40]. MDM2 gene amplification is closely associated with DFS and OS, indicating that MDM2 amplification can be used for predicting the survival of NSCLC patients who experienced surgical treatment [41]. The let-7 family members function as tumor suppressors in lung cancer, which can be repressed by Lin-28 and inhibit cell proliferation [42]. Through suppressing the transcription of POLR2A, the type II glycoprotein CD26 plays an inhibitory role in tumor growth [43]. Therefore, let-7 family members and POLR2A targeting circ_MDM2_000139 might be also correlated with the progression of NSCLC. However, after consulting the literature, there were few reports providing direct relationship between let-7 family members, POLR2A, and XAV939.

Increased BIRC6 protein level may be a predictive factor for chemoresistance and an adverse prognostic marker for NSCLC, and inhibiting BIRC6 may be a useful method for treating the tumor [44]. MiR-133b is found to be able to decrease cisplatin resistance, and its overexpression suppresses cell growth and invasion in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC via regulating glutathione-S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) [45]. Through reducing CDC25C and CDC2 protein levels, the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibitor is implicated in antiproliferative activity and tumor progression in lung cancer cells and thus can be applied for the treatment of lung cancer [46]. MiR-221 and miR-222 are involved in multiple human cancers, which play tumor-suppressive roles in lung cancer and may be promising targets for the therapy of the disease [47]. These indicated that miR-133b targeting circ_BIRC6_001271 and miR-221-3p/miR-222-3p targeting circ_CDC25C_002079 might be implicated in the pathogenesis of NSCLC. Dicer is important for microRNA-mediated silencing and other RNA interference, which were profoundly involved in cancer related networks [48]. Díaz-García et al. found that the DICER1 expression level varied among cancer specimens and 66% cancer samples had decreased DICER1 mRNA. Besides, the median overall survival (OS) of those with low level of DICER1 mRNA was substantially reduced [49]. In addition, the copy number variation of DICER1 correlates well with the expression and survival of NSCLC, and the increased expression DICER1 increases the survival [50]. In our study, we found that circ_DICER1_000834 was downregulated in the A549 and HCC-827 cells after treatment with the XAV939. The reports indicated that the DICER1 in the pathogenesis of NSCLC and circ_DICER1_000834 might play an important during the XAV939 treatment for NSCLC.

In conclusion, 106 DE-circRNAs between the treatment and control groups were identified. Besides, let-7 family members and POLR2A targeting circ_MDM2_000139, miR-16-5p/miR-134-5p targeting circ_ATF2_001418, miR-133b targeting circ_BIRC6_001271, and miR-221-3p/miR-222-3p targeting circ_CDC25C_002079 might be involved in the function during the treatment of NSCLC by XAV939. However, the roles of these RNAs and regulatory relationships in treatment of NSCLC by XAV939 needed to be further confirmed by experimental research studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by The Study of the Correlation Between ROCK1 and the Metastasis of Lung Cancer (Project number: SCZSY201728).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional Points

Highlights. (1) There were 106 differentially expressed circRNAs between the XAV939-treated NSCLC cells and control. (2) ATF2 was enriched in the TNF signaling pathway. (3) Circ_MDM2_000139, circ_ATF2_001418, circ_CDC25C_002079, and circ_BIRC6_001271 were key circRNAs in XAV939-treated NSCLC cells.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

The relative expression levels of key DE-circRNAs were detected by the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The primer information is shown in the Supplementary Table 1.

References

- 1.Torre L. A., Siegel R. L., Jemal A. Advances in Experimental Medicine & Biology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. Lung cancer statistics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison E. J., Novotny P. J., Sloan J. A., et al. Emotional problems, quality of life, and symptom burden in patients with lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2017;18(5):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi S., Ryu E. Effects of symptom clusters and depression on the quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2018;27(1) doi: 10.1111/ecc.12508.e12508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mcguire S. World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Advances in Nutrition. 2016;7(2):p. 418. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Z., Fillmore C. M., Hammerman P. S., Kim C. F., Wong K. K. Non-small-cell lung cancers: a heterogeneous set of diseases. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(8):535–546. doi: 10.1038/nrc3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhurst T. Staging of non-small-cell lung cancer. Seminars in Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2008;29(3):248–260. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo W., Shen F., Xiao W., Chen J., Pan F. Wnt inhibitor XAV939 suppresses the viability of small cell lung cancer NCI-H446 cells and induces apoptosis. Oncology Letters. 2017;14(6):6585–6591. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C., Zheng X., Han Y., Lv Y., Lan F., Zhao J. XAV939 inhibits the proliferation and migration of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells through the WNT pathway. Oncology Letters. 2018;15(6):8973–8982. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang G., Li S., Yang N., Zou Y., Zheng D., Xiao T. Recent progress in circular RNAs in human cancers. Cancer Letters. 2017;404:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao J. T., Zhao S. H., Liu Q. P., et al. Over-expression of CircRNA_100876 in non-small cell lung cancer and its prognostic value. Pathology—Research and Practice. 2017;213(5):453–456. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S., Zeng X., Ding T., et al. Microarray profile of circular RNAs identifies hsa_circ_0014130 as a new circular RNA biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:p. 1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21300-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y., Zhao H., Zhang L. Identification of the tumor-suppressive function of circular RNA FOXO3 in non-small cell lung cancer through sponging miR-155. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2018;17(6):p. 7692. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao F., Han Y., Liu Z., Zhao Z., Li Z., Jia K. circFADS2 regulates lung cancer cells proliferation and invasion via acting as a sponge of miR-498. Bioscience Reports. 2018;38(4) doi: 10.1042/bsr20180570.BSR20180570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ran M., Chen B., Li Z., et al. Systematic identification of long noncoding RNAs in immature and mature porcine testes1. Biology of Reproduction. 2016;94(4):p. 77. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.136911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S. L. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology. 2013;14(4):p. R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrow J., Frankish A., Gonzalez J. M., et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for the ENCODE Project. Genome Research. 2012;22(9):1760–1774. doi: 10.1101/gr.135350.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D., Salzberg S. L. TopHat-Fusion: an algorithm for discovery of novel fusion transcripts. Genome Biology. 2011;12(8):p. R72. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X. O., Dong R., Zhang Y., et al. Diverse alternative back-splicing and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Research. 2016;26(9):1277–1287. doi: 10.1101/gr.202895.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer L. R., Zweig A. S., Hinrichs A. S., et al. The UCSC genome browser database: extensions and updates 2013. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;40:D918–D923. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lun A. T., Chen Y., Smyth G. K. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1418. New York, NY, USA: Humana Press; 2016. It’s DE-licious: a recipe for differential expression analyses of RNA-seq experiments using quasi-likelihood methods in edgeR; p. p. 391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G., Wang L. G., Han Y., He Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics-a Journal of Integrative Biology. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young M. D., Wakefield M. J., Smyth G. K., Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biology. 2010;11(2):1–12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotera M., Moriya Y., Tokimatsu T., Kanehisa M., Goto S. Encyclopedia of Metagenomics. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 2015. KEGG and GenomeNet, new developments, metagenomic analysis; pp. 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panda A. C., Dudekula D. B., Abdelmohsen K., Gorospe M. Analysis of circular RNAs using the web tool CircInteractome. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2018;1724:43–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7562-4_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rong D., Sun H., Li Z., et al. An emerging function of circRNA-miRNAs-mRNA axis in human diseases. Oncotarget. 2017;8(42):73271–73281. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaul U. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biology. 2003;5(1):p. R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piñero J., Queralt-Rosinach N., Bravo À., et al. DisGeNET: a discovery platform for the dynamical exploration of human diseases and their genes. Database. 2015;2015(3):p. bav028. doi: 10.1093/database/bav028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dweep H., Sticht C., Pandey P., Gretz N. miRWalk—database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2011;44(5):839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohl M., Wiese S., Warscheid B. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 696. New York, NY, USA: Humana Press; 2011. Cytoscape: software for visualization and analysis of biological networks; pp. 291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glažar P., Papavasileiou P., Rajewsky N. circBase: a database for circular RNAs. RNA. 2014;20(11):1666–1670. doi: 10.1261/rna.043687.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao J., Wu J., Xu T., Yang Q., He J., Song X. IRESfinder: identifying RNA internal ribosome entry site in eukaryotic cell using framed k-mer features. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2018;45(7):403–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhidong T., Xuecang L., Jianmei Z., et al. TRCirc: a resource for transcriptional regulation information of circRNAs. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2018 doi: 10.1093/bib/bby083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y., Zhou B. P. TNF-α/NF-κB/snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;102(4):639–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang S., Yan Y., Cheng Z., Hu Y., Liu T. Sotetsuflavone suppresses invasion and metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer A549 cells by reversing EMT via the TNF-α/NF-κB and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cell Death Discovery. 2018;4:p. 1. doi: 10.1038/s41420-018-0026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang S., Ren H., Chen M., et al. miRNA-204 suppresses human non-small cell lung cancer by targeting ATF2. Chest. 2016;149(4):p. A300. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarro A., Diaz T., Gallardo E., et al. Prognostic implications of miR-16 expression levels in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;103(5):411–415. doi: 10.1002/jso.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun C. C., Li S. J., Li D. J. Hsa-miR-134 suppresses non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) development through down-regulation of CCND1. Oncotarget. 2016;7(24):35960–35978. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin Q., Wei F., Zhang J., Li B. miR-134 suppresses the migration and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting ITGB1. Oncology Reports. 2017;37(2):823–830. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang D. H., Zhang L. Y., Liu D. J., Yang F., Zhao J. Z. Expression and significance of MMP-9 and MDM2 in the oncogenesis of lung cancer in rats. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2014;7(7):585–588. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dworakowskaa D., Jassemc E., Jassemb J., Peters B., Dziadziuszkob R., et al. MDM2 gene amplification: a new independent factor of adverse prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Lung Cancer. 2004;43(3):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin P., Gong Z., Zhong Z., et al. Lin-28 reactivation is required for let-7 repression and proliferation in human small cell lung cancer cells. Molecular & Cellular Biochemistry. 2011;355(1-2):257–263. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0862-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohji Y., Mutsumi H., Hiroko M., et al. Nuclear localization of CD26 induced by a humanized monoclonal antibody inhibits tumor cell growth by modulating of POLR2A transcription. PLoS One. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062304.e62304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong X., Lin D., Low C., et al. Elevated expression of BIRC6 protein in non-small-cell lung cancers is associated with cancer recurrence and chemoresistance. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8(2):161–170. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e31827d5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin C., Xie L., Lu Y., Hu Z., Chang J. miR-133b reverses cisplatin resistance by targeting GSTP1 in cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2018;41(4):2050–2058. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senju M., Sueoka N., Sato A., et al. Hsp90 inhibitors cause G2/M arrest associated with the reduction of Cdc25C and Cdc2 in lung cancer cell lines. Journal of Cancer Research & Clinical Oncology. 2006;132(3):150–158. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamashita R., Sato M., Kakumu T., et al. Growth inhibitory effects of miR-221 and miR-222 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Medicine. 2015;4(4):551–564. doi: 10.1002/cam4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foulkes W. D., Priest J. R., Duchaine T. F. DICER1: mutations, microRNAs and mechanisms. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(10):662–672. doi: 10.1038/nrc3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Díaz-García C. V., Agudo-López A., Pérez C., et al. DICER1, DROSHA and miRNAs in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: implications for outcomes and histologic classification. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(5):1031–1038. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Czubak K., Lewandowska M. A., Klonowska K., et al. High copy number variation of cancer-related microRNA genes and frequent amplification of DICER1 and DROSHA in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):23399–23416. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The relative expression levels of key DE-circRNAs were detected by the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The primer information is shown in the Supplementary Table 1.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.