Abstract

Seven members of the aquaporin (AQP) family are expressed in different regions of the kidney. AQP1–4 are localized in plasma membranes of renal epithelial cells and are intimately involved in water reabsorption by the kidney. AQP7 is also localized in the plasma membrane and may facilitate glycerol transport. AQP6 and AQP11 are localized within the cell, with AQP6 involved in anion transport and AQP11 water transport. Mutations in AQP2 can result in diabetes insipidus, whereas mutations in other AQPs have not yet been shown to be disease-associated. Genetic polymorphisms may contribute to the susceptibility to defects in urine concentrating mechanisms associated with some diseases. Most of the AQPs are subject to transcriptional regulation and post-translational modifications by a range of biological modifiers. As a result a number of chronic kidney and systemic diseases produce changes in the abundance of AQPs. The more recent developments in this field are reviewed.

Keywords: Kidney, Aquaporins, Water transport, Vasopressin, Membrane channels

1. Introduction

Ever since the first glimpse of the red cell water channel was reported in 1986 our knowledge of these channel proteins has developed at an amazing speed (Benga et al., 1986). The importance of these channels in the kidney was quickly recognized as the reabsorption of water and the concentration of glomerular filtrate are essential functions required to sustain life in mammals. In humans, over 150 L of aqueous fluid is filtered through the kidneys each day, but only around 2 L are voided in urine illustrating the importance of this function. Several aquaporins (AQPs), membrane-inserted water channels, play a vital role in this process (Noda et al., 2010). Some renal aquaporins may also be involved in glycerol and ion transport or have functions not yet recognized. Their importance and functional role is being illuminated through studies in vitro and in vivo, particularly in mice with mutations in AQP genes. Other studies have identified diseases where AQP expression or function in the kidney is modified and include a wide range of chronic kidney diseases and renal cancers (Bedford et al., 2003; Noda et al., 2010; Schrier, 2006). In several systemic diseases water handling may also be impaired including hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and a variety of hormonal imbalances.

As well as reviewing the most recent research on renal AQPs, this article will suggest research strategies that may prove to be most rewarding in coming years. These suggestions come with the recognition that major advances in our understanding of renal AQPs will most likely in the next decade arise from new discoveries and methodological approaches that surface.

2. Localization and function of aquaporins in the kidney

The AQPs as a class are tetrameric proteins made from identical ~30-kDa monomers (Verkman, 2011). X-ray crystallography has revealed that each monomer has six membrane-spanning helical domains and two short helical segments. Each monomer contains a narrow aqueous pore that is about 25 Å in length and 2.8 Å in diameter.

Seven isoforms of aquaporin are known to be expressed in the kidney (Table 1). AQP1 and AQP2 are responsible for much of the water reabsorption from the glomerular filtrate and have been the primary focus of research on renal AQPs. In nephrons, AQP1 is localized in the apical and basolateral membranes of proximal tubules and descending thin limbs of Henle, whereas AQP2 is exclusively expressed in principal cells of the collecting duct and is incorporated in apical membranes and intracellular vesicles. AQP3 and AQP4 are localized in the basolateral membrane of principal cells of the collecting duct and will normally produce a net flow of water into the interstitium. AQP7, which is localized in apical membranes of the S3 segment of proximal tubules, transports both water and glycerol. In contrast to these AQPs, AQP6 and AQP11 are localized in intracellular membranes: AQP6 in vesicles within intercalated cells of the collecting duct and AQP11 in the endoplasmic reticulum of proximal tubules. AQP6 may function primarily as an anion transporter (Ikeda et al., 2002) whereas the properties of AQP11 are not clear. AQP11 may be involved in water transport (Yakata et al., 2011), but interestingly, knock-out mice lacking AQP11 develop polycystic kidney disease (Morishita et al., 2005).

Table 1.

Renal expression of aquaporins.

| Aquaporin | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|

| AQP1 | Proximal tubule, descending thin limbs of Henle - AP & BL, Vasa Recta | Water |

| AQP2 | Collecting duct - principal cells AP | Water, AVP - responsive |

| AQP3 | Collecting duct - principal cells BL | Water, AVP - responsive |

| AQP4 | Collecting duct - principal cells BL | Water |

| AQP6 | Collecting duct - intercalated cells-Ves | Anions, water |

| AQP7 | Proximal tubule - S3 AP | Glycerol |

| AQP11 | Proximal tubule ER | Water? |

AP is the apical membrane and BL the basolateral membrane.

3. Regulation of water retention by vasopressin

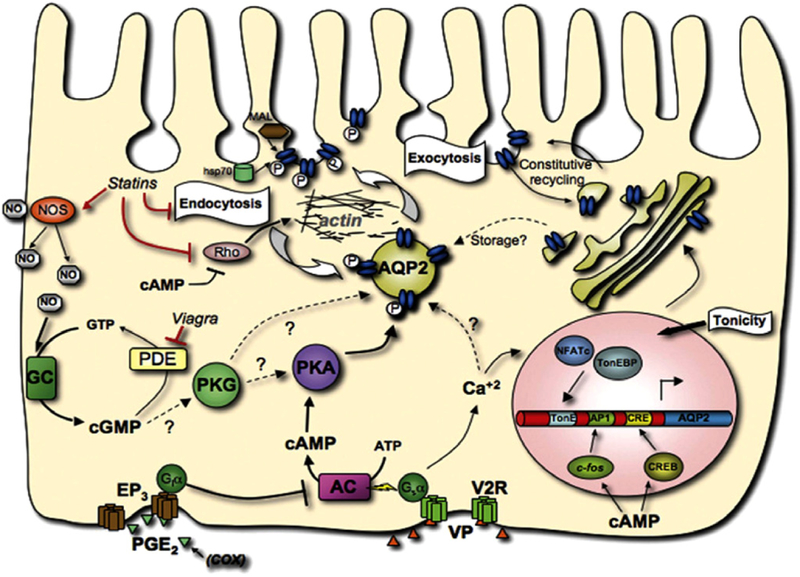

The fine tuning of water retention is regulated in principal cells of the collecting duct by the peptide hormone, vasopressin. Vasopressin stimulation of a specific receptor in the plasma membrane increases the AQP2 concentration in the apical membrane as depicted in Fig. 1 by a complex set of signals that are gradually being defined. A key event is the phosphorylation of serine-256 of AQP2 that is present in intracellular vesicles by protein kinase A. This phosphorylation of AQP2 appears to modify the cytoskeletal network and precipitate the trafficking of AQP2-rich vesicles to the plasma membrane (Noda et al., 2008). It may stimulate the water transport properties of the plasma membrane as well as increasing the concentration of AQP2 in the membrane (Eto et al., 2010). A near doubling of water permeability was observed in proteoliposomes containing recombinant phosphorylated AQP2, but how native principal cell plasma membranes respond remains to be determined. Other regulatory components of the process include pathways associated with cAMP and cGMP. As shown in Fig. 1, this trafficking can be modified by statins, phosphodiesterase inhibitors (e.g., Viagra), and cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Chronic vasopressin stimulation increases the expression of AQP2 through phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) (Matsumura et al., 1997).

Fig. 1.

AQP2 trafficking in principal cells This model depicts how the interaction of PGE2 or vasopressin (VP) with either the PGE2 receptor (EP3) or the vasopressin receptor (V2R) in the basolateral membrane of a principal cell results in the incorporation of AQP2 (blue ovals) into the apical membrane. The phosphorylation of AQP2 by protein kinase A (PKA) signals its translocation from an intracellular vesicle to the plasma membrane. Steps that regulate this process are shown and revolve around guanylate cyclase (GC), adenylate cyclase (AC) and calcium (Ca2+). Taken with permission from Bouley et al. (2008).

4. Posttranslational modifications

The AQPs, especially AQP2, are subject to a variety of posttranslational modifications that affect their function (Moeller et al., 2011). These include glycosylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination. These changes affect their localization within the cell, their activity and their processing.

Phosphorylation of Ser256 in AQP2 has already been mentioned as playing an important role in stimulating its trafficking from intracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane as shown in Fig. 1 (Fushimi et al., 1997; Katsura et al., 1997). Many of the effects resulting from the phosphorylation of Ser256 and the COOH terminal of AQPs, including changes in the regulation of water transport remain controversial as reviewed by Moeller et al. (2011).

Most of the renal AQPs have N-linked consensus glycosylation sites as reviewed by Buck et al. (2004) and Moeller et al. (2011). This includes AQP1, AQP2, AQP3 and AQP4 which may be fully or partially glycosylated. The role of this glycosylation is uncertain. In AQP2 it may be important for some of the trafficking that occurs within the cell, but the protein is equally functional when glycosylation is blocked by tunicamycin (Baumgarten et al., 1998; Hendriks et al., 2004).

Ubiquitination of AQPs appears to trigger their internalization and subsequent degradation. A short-chain ubiquitin can be attached to the N-terminal COOH group (K270) of AQP2 (Kamsteeg et al., 2006). Kamsteeg et al. proposed that ubiquinated-AQP2 is sorted to intraendosomal vesicles of multivesicular bodies and ultimately targeted to lysosomes for degradation or to exosomes for externalization (Kamsteeg et al., 2006).

5. Mutations in AQP genes

The only truly defined renal, genetic diseases involving AQPs are those with mutations in AQP2 (Noda et al., 2010). Mutations in both AQP2 and the vasopressin V2 receptor can cause nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Mutations in AQP1 do not cause overt disease, but do cause a defect in urine concentrating ability during fluid deprivation (King et al., 2001). Mutations in the aquaglyceroporin, AQP7, appear to be associated with perturbations in glycerol transport in the only individual reported to lack the protein (Kondo et al., 2002). This individual was, however, asymptomatic. Knock-out mice with an absence of these AQPs have similar phenotypes to humans (Noda et al., 2010). Mice that do not express AQP3 have a defect in their ability to concentrate urine (Ma et al., 2000) but a similar phenotype has not yet been reported in humans. AQP4-deficient mice have only a mild concentrating defect (Ma et al., 1997). More explicit phenotypes of these mice containing deletions or mutations in AQP genes that affect the kidney have been described in recent reviews (Noda et al., 2010; Verkman, 2006).

Genetic polymorphisms that result in changes in the expression of a gene or the functional activity of the expressed protein can also contribute to disease. How genetic variation in AQP may possibly play a role in disease with an alteration in water retention was recently described (Fabrega et al., 2011). Patients with liver cirrhosis and a particular AQP1 variant were less able to concentrate their urine compared to other genotypes. It was proposed that this polymorphism may be associated with the water retention that often occurs in conjunction with liver cirrhosis in some patients. The polymorphism occurred in the untranslated 3′ region which may influence the stability of expressed mRNA. They were able to confirm that a lower expression of the gene sequence containing the aberrant polymorphism occurred in vitro, consistent with it causing an effect. Such studies are preliminary and require verification in larger groups before strong conclusions can be drawn. However, they do illustrate the promise of this approach in identifying causative genetic changes contributing to disease.

6. Changes in AQP functional activity with disease

A variety of pathophysiological changes associated with renal and systemic diseases can modify AQP functional activity in the kidney. Such changes could result from an array of different causes including impaired functioning in glomerular and renal epithelial cells and compensatory changes related to altered glomerular filtration rates. Bedford et al. (2003) were among the first to describe changes in AQP expression in specific renal diseases. Using a semi-quantitative analysis they reported changes in AQP1, AQP2, AQP3 and AQP4 expression associated with a number of kidney diseases, including mesangial proliferative glomerular nephritis, lupus nephritis, interstitial nephritis, nephrosclerosis, crescentic glomerulonephritis, chronic lithium nephropathy, chronic glomerulonephritis, and minimal change disease. Notably, the expression of AQP1 was greatly increased in glomerular endothelial cells in virtually all of these diseases. In contrast, the abundance of AQP2 and AQP3 in the collecting duct was in most diseases reduced. AQPs may also play a role in fluid flow into cysts associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), the most frequently inherited nephropathy (Terryn et al., 2011). About two thirds of cysts have been found to contain either AQP1 or AQP2, but not both. This exclusivity suggests that the cysts originate from cells in different parts of the nephron. The absence of AQPs in some cysts suggests that AQPs may not play a role in the formation of all cysts. Cysts containing AQP2 are the most common and drugs that act as antagonists to the vasopressin V2 receptor appear to be promising in reducing the size of cysts (Higashihara et al., 2011). Experiments with genetically modified mice also show a relationship between PKD and AQPs. Mice heterozygous for mutations in polycystin-1, a gene associated with the development of PKD, over-concentrate their urine due to changes in AQP expression and function (Ahrabi et al., 2007), and mice lacking AQP11 develop PKD (Morishita et al., 2005). More recent studies which have more quantitatively measured changes in AQP that occur during renal disease or trauma are shown in Table 2. Likewise, a number of systemic diseases affect the abundance of AQPs in the kidney and may alter water handling as a result. One qualification about these studies is that they have measured the expression of only some of the AQPs that play a major role in water handling, AQPs1–4. More extensive profiles of the AQPs may uncover additional changes.

Table 2.

Diseases associated with changes in the abundance of aquaporins.

| Disease | AQPs modified | References |

|---|---|---|

| Renal disease | ||

| Ischemia/reperfusion injury | AQP1↓, AQP2↓, AQP3↓ | Hussein et al. (2011) |

| Proximal renal tubular acidosis | AQP2↑ | Lo et al. (2011) |

| Acute renal transplant rejection | AQP2↓ | Chen et al. (2010) |

| Congenital hydronephrosis | AQP1↓, AQP2↓, AQP3↓, AQP4↓ | Wen et al. (2009) |

| Systemic disease | ||

| Ureteral obstruction 7 weeks | AQP1↑, AQP2↑, AQP3↑ | Wang et al. (2012) |

| Statin therapy | AQP2↑ | Li et al. (2011) |

| Salt-sensitive hypertension | AQP1↓, AQP2↓, AQP4↑ | Procino et al. (2011) |

| Heart failure | AQP2↑ | Lutken et al. (2009) |

| Lithium therapy | AQP2↓, AQP3↓ | Kwon et al. (2000) |

| NSAID therapy | AQP2↓ | Baggaley et al. (2010) |

| Ageing | AQP2↓, AQP3↓ | Sands (2009) |

7. Future research strategies

It is always difficult to predict which avenues of research will be most profitable in the future for increasing our understanding of renal AQPs and identifying ways their expression or functional activity can be modified. Four areas that could play an important future role include (a) genetic/DNA analyses to determine the impact of genetic variation, (b) expression analyses to assess how changes in physiological states, including disease states, alter gene expression, (c) studies of genetically modified mice, and (d) analyses of urinary exosomes to gain insights into nephron structure and function.

7.1. Genetic analyses

As the cost of DNA sequencing decreases, the prospect becomes more likely that more thorough DNA analyses will show the contribution that rare variants and genetic networks make to changes in protein function. It has been estimated that the DNA sequencing of any sample should effectively be repeated 28 times to obtain accurate sequences. The 1000 genomes project will initially aim for 4× coverage with sequencing up to 50× in areas of interest (www.1000genomes.org). This will provide a wealth of data, of which will undoubtedly be useful for studying AQP genes.

7.2. Expression analyses

Studies on the expression of renal AQPs at the mRNA and protein levels are likely to continue to expand our knowledge of their dynamic state in response to changing environments. An increased focus is likely to be on regulation of transcription as the genetic elements responsible for expression changes are identified.

7.3. Genetically modified mice

As discussed above, the phenotypes of knock-out mice not expressing the various renal AQPs have been described. Such mice should continue to be useful in defining the specific roles of AQPs in various physiological and pathophysiological states. Double knock-outs, conditional knock-outs, and knock-ins may all make valuable contributions to this research area.

7.4. Exosomes

The biological role, if any, of exosomes is still not clear. These are small (40–100 nm) membranous vesicles released from cells that may contain proteins, RNA and signaling molecules. They are excreted in urine and analysis of the human urinary exosomal proteome suggests that cells from each part of the nephron release exosomes into urine (Pisitkun et al., 2004). One hypothesis proposed for the function of exosomes in the kidney is that they provide an additional means for communication between upstream and downstream regions of the nephron (Camussi et al., 2010; van Balkom et al., 2011). Receptors on the surface of downstream cells could facilitate specific cell targeting. Either fusion of the vesicles with the plasma membrane or endocytosis of the vesicles could lead to the release of exosomal contents. Street and colleagues have recently demonstrated that exosomes released from cultured collecting duct cells after stimulation with desmopressin are capable of modifying the water permeability of other cells (Street et al., 2011). Renal exosomes appear to account for much of the AQP identified in urine (van Balkom et al., 2011). These particles may prove useful in establishing diagnoses, following therapeutic progression, and in increasing our understanding of AQP function.

8. Summary

AQPs in the kidney play a vital role in controlling water retention in the body. The bulk of filtered water is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule through the activity of AQP1. The process is regulated, however, primarily through the interaction of vasopressin with principal cells of the collecting duct and its effects on AQP2 and AQP3. Changes in AQP2 or the vasopressin V2 receptor lead to disease. The functional role of several of the AQPs, primarily AQP6, AQP7 and AQP11 is not clear. Future research seems destined to clarify their roles and the association that each of the AQPs has with renal disease.

References

- Ahrabi AK, Terryn S, Valenti G, Caron N, Serradeil-Le Gal C, Raufaste D, Nielsen S, Horie S, Verbavatz JM, Devuyst O, 2007. PKD1 haploinsufficiency causes a syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis in mice. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 18 (6), 1740–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley E, Nielsen S, Marples D, 2010. Dehydration-induced increase in aquaporin-2 protein abundance is blocked by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 298 (4), F1051–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten R, Van De Pol MH, Wetzels JF, Van Os CH, Deen PM, 1998. Glycosylation is not essential for vasopressin-dependent routing of aquaporin-2 in transfected Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 9 (9), 1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford JJ, Leader JP, Walker RJ, 2003. Aquaporin expression in normal human kidney and in renal disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 14 (10), 2581–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benga G, Popescu O, Pop VI, Holmes RP, 1986. P-(Chloromercuri)benzenesulfonate binding by membrane proteins and the inhibition of water transport in human erythrocytes. Biochemistry 25 (7), 1535–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouley R, Hasler U, Lu HA, Nunes P, Brown D, 2008. Bypassing vasopressin receptor signaling pathways in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Seminars in nephrology 28 (3), 266–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck TM, Eledge J, Skach WR, 2004. Evidence for stabilization of aquaporin-2 folding mutants by N-linked glycosylation in endoplasmic reticulum. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 287 (5), C1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L, 2010. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney international 78 (9), 838–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Zang CS, Zhang JZ, Wang WG, Wang JG, Zhou HL, Fu YW, 2010. The changes of aquaporin 2 in the graft of acute rejection rat renal transplantation model. Transplantation Proceedings 42 (5), 1884–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto K, Noda Y, Horikawa S, Uchida S, Sasaki S, 2010. Phosphorylation of aquaporin-2 regulates its water permeability. The Journal of biological chemistry 285 (52), 40777–40784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega E, Berja A, Garcia-Unzueta MT, Guerra-Ruiz A, Cobo M, Lopez M, Bolado-Carrancio A, Amado JA, Rodriguez-Rey JC, Pons-Romero F, 2011. Influence of aquaporin-1 gene polymorphism on water retention in liver cirrhosis. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 46 (10), 1267–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushimi K, Sasaki S, Marumo F, 1997. Phosphorylation of serine 256 is required for cAMP-dependent regulatory exocytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. The Journal of biological chemistry 272 (23), 14800–14804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks G, Koudijs M, van Balkom BW, Oorschot V, Klumperman J, Deen PM, van der Sluijs P, 2004. Glycosylation is important for cell surface expression of the water channel aquaporin-2 but is not essential for tetramerization in the endoplasmic reticulum. The Journal of biological chemistry 279 (4), 2975–2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashihara E, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Grantham JJ, Bae K, Watnick TJ, Horie S, Nutahara K, Ouyang J, Krasa HB, Czerwiec FS, 2011. Tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: three years’ experience. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 6 (10), 2499–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein AA, El-Daken ZH, Barakat N, Abol-Enein H, 2011. Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury: possible role of aquaporins. Acta Physiology, in press. doi: 10.1111/j:1748-1716.2011,02372.x.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Beitz E, Kozono D, Guggino WB, Agre P, Yasui M, 2002. Characterization of aquaporin-6 as a nitrate channel in mammalian cells. Requirement of pore-lining residue threonine 63. The Journal of biological chemistry 277 (42), 39873–39879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamsteeg EJ, Hendriks G, Boone M, Konings IB, Oorschot V, van der Sluijs P, Klumperman J, Deen PM, 2006. Short-chain ubiquitination mediates the regulated endocytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (48), 18344–18349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsura T, Gustafson CE, Ausiello DA, Brown D, 1997. Protein kinase A phosphorylation is involved in regulated exocytosis of aquaporin-2 in transfected LLC-PK1 cells. The American journal of physiology 272 (6 Pt 2), F817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Choi M, Fernandez PC, Cartron JP, Agre P, 2001. Defective urinary-concentrating ability due to a complete deficiency of aquaporin-1. The New England journal of medicine 345 (3), 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Kuriyama H, Makino Y, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Maeda N, Nagaretani H, Kihara S, Kurachi Y, Nakamura T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, 2002. Human aquaporin adipose (AQPap) gene. Genomic structure, promoter analysis and functional mutation. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS 269 (7), 1814–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon TH, Laursen UH, Marples D, Maunsbach AB, Knepper MA, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S, 2000. Altered expression of renal AQPs and Na(+) transporters in rats with lithium-induced NDI. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 279 (3), F552–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Zhang Y, Bouley R, Chen Y, Matsuzaki T, Nunes P, Hasler U, Brown D, Lu HA, 2011. Simvastatin enhances aquaporin-2 surface expression and urinary concentration in vasopressin-deficient Brattleboro rats through modulation of Rho GTPase. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 301 (2), F309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YF, Yang SS, Seki G, Yamada H, Horita S, Yamazaki O, Fujita T, Usui T, Tsai JD, Yu IS, Lin SW, Lin SH, 2011. Severe metabolic acidosis causes early lethality in NBC1 W516X knock-in mice as a model of human isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney international 79 (7), 730–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutken SC, Kim SW, Jonassen T, Marples D, Knepper MA, Kwon TH, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S, 2009. Changes of renal AQP2, ENaC, and NHE3 in experimentally induced heart failure: response to angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 297 (6), F1678–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Song Y, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS, 2000. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in mice lacking aquaporin-3 water channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (8), 4386–4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS, 1997. Generation and phenotype of a transgenic knockout mouse lacking the mercurial-insensitive water channel aquaporin-4. Journal of Clinical Investigation 100 (5), 957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Uchida S, Rai T, Sasaki S, Marumo F, 1997. Transcriptional regulation of aquaporin-2 water channel gene by cAMP. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 8 (6), 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller HB, Olesen ET, Fenton RA, 2011. Regulation of the water channel aquaporin-2 by posttranslational modification. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 300 (5), F1062–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita Y, Matsuzaki T, Hara-chikuma M, Andoo A, Shimono M, Matsuki A, Kobayashi K, Ikeda M, Yamamoto T, Verkman A, Kusano E, Ookawara S, Takata K, Sasaki S, Ishibashi K, 2005. Disruption of aquaporin-11 produces polycystic kidneys following vacuolization of the proximal tubule. Molecular and cellular biology 25 (17), 7770–7779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Horikawa S, Kanda E, Yamashita M, Meng H, Eto K, Li Y, Kuwahara M, Hirai K, Pack C, Kinjo M, Okabe S, Sasaki S, 2008. Reciprocal interaction with G-actin and tropomyosin is essential for aquaporin-2 trafficking. Journal of Cell Biology 182 (3), 587–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y, Sohara E, Ohta E, Sasaki S, 2010. Aquaporins in kidney pathophysiology. Nature Reviews Nephrology 6 (3), 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA, 2004. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (36), 13368–13373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procino G, Romano F, Torielli L, Ferrari P, Bianchi G, Svelto M, Valenti G, 2011. Altered expression of renal aquaporins and alpha-adducin polymorphisms may contribute to the establishment of salt-sensitive hypertension. American journal of hypertension 24 (7), 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands JM, 2009. Urinary concentration and dilution in the aging kidney. Seminars in nephrology 29 (6), 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrier RW, 2006. Body water homeostasis: clinical disorders of urinary dilution and concentration. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 17 (7), 1820–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street JM, Birkhoff W, Menzies RI, Webb DJ, Bailey MA, Dear JW, 2011. Exosomal transmission of functional aquaporin 2 in kidney cortical collecting duct cells. J Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terryn S, Ho A, Beauwens R, Devuyst O, 2011. Fluid transport and cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1812 (10), 1314–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Balkom BW, Pisitkun T, Verhaar MC, Knepper MA, 2011. Exosomes and the kidney: prospects for diagnosis and therapy of renal diseases. Kidney international 80 (11), 1138–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman AS, 2006. Roles of aquaporins in kidney revealed by transgenic mice. Seminars in nephrology 26 (3), 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman AS, 2011. Aquaporins at a glance. Journal of Cell Science 124 (Pt 13), 2107–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakata K, Tani K, Fujiyoshi Y, 2011. Water permeability and characterization of aquaporin-11. Journal of Structural Biology 174 (2), 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Yuan W, Kwon TH, Li Z, Wen J, Topcu SO, Djurhuus JC, Nielsen S, Frokiaer J, 2012. Age-related changes in expression in renal AQPs in response to congenital, partial, unilateral ureteral obstruction in rats. Pediatric Nephrology 27 (1), 83–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen JG, Li ZZ, Zhang H, Wang Y, Wang G, Wang Q, Nielsen S, Djurhuus JC, Frokiaer J, 2009. Expression of renal aquaporins is down-regulated in children with congenital hydronephrosis. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology 43 (6), 486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]