Abstract

Aims:

To examine how the process of change prescribed in Kotter’s change model applies in implementing team huddles, and assess the impact of the execution of early change phases on change success in later phases.

Background:

Kotter’s model can help guide hospital leaders to implement change and potentially improve success rates. However, the model is understudied, particularly in healthcare.

Methods:

We followed eight hospitals implementing team huddles for two years, interviewing change teams quarterly to inquire about implementation progress. We assessed how the hospitals performed in the three overarching phases of the Kotter model, and examined whether performance in the initial phase influenced subsequent performance.

Results:

In half of the hospitals, change processes were congruent with Kotter’s model, where performance in the initial phase influenced their success in subsequent phases. In other hospitals, change processes were incongruent with the model, and their success depended on implementation scope and strategies employed.

Conclusions:

We found mixed support for the Kotter model. It better fits implementation that aims spreading to multiple hospital units. When the scope is limited, changes can be successful even when steps are skipped.

Implications for Nursing Managements:

Kotter’s model can be a useful guide for nurse managers implementing changes.

Keywords: Hospital, Change, Implementation, Huddle, TeamSTEPPS

INTRODUCTION

Care quality and patient safety are among the top priorities of healthcare leaders in the US and internationally (Parand et al. 2014, American College of Healthcare Executives 2016), and nurse leaders often play a central role in implementing evidence-based practices (EBPs) and other innovations to improve quality and safety (Stetler et al. 2014). However, quality variation persists, suggesting that leaders are not equally effective in implementing EBPs. To improve effectiveness, implementation process models can offer a useful guide to implementation leaders (Nilsen 2015). These models typically depict change processes as a series of steps or phases, guiding implementation efforts toward a desired goal (Nilsen 2015).

Kotter’s model of change (1996) is a popular process model for change management (Appelbaum et al. 2012). It is gaining recognition among healthcare leaders who use it to guide implementation practice in the US and internationally (e.g. Dolansky et al. 2013, Maclean & Vannet 2016, Small et al. 2016). Although Kotter’s model has considerable face validity and its steps are empirically supported, a holistic evaluation of the model is absent (Appelbaum et al. 2012).

This study examines the implementation of team huddles in eight hospitals. Team huddles are an effective patient safety tool (Goldenhar et al. 2013, Glymph et al. 2015), but are not always successfully implemented (Whyte et al. 2009, Townsend et al. 2017). To enhance our understanding of implementation successes and failures, we examine how the process of change prescribed in the Kotter model unfolds in practice. Specifically, we explore whether the development of change phases vary from the prescribed order and what impact the execution of early change phases has on change success in later phases. We seek to contribute to the nursing leadership literature by examining variation in the change process and the implications of such variation for change leadership practice. Our findings also contribute to implementation science by providing empirical evidence on the application of the Kotter model in EBP implementation.

BACKGROUND

Communication and team huddles

While many issues contribute to poor quality and patient safety, communication issues have been identified as the leading cause in 60–80% of adverse events (Woolf et al. 2004, The Joint Commission 2015). Rooted in the high-reliability organization literature, team huddles have been shown to improve communication among clinicians and enhance patient safety (Goldenhar et al. 2013). Team huddles (also referred to as briefs) are short briefing sessions, commonly held among clinical and other staff at the beginning of a shift or procedure, to discuss pertinent patient and care information. Huddles help form the team, establish plans and expectations, and prepare for any issues and contingencies the team might face (Goldenhar et al. 2013, AHRQ 2014b). Team huddles can improve patient safety by strengthening the safety culture and sustaining high reliability (Provost et al. 2015). In a variety of healthcare settings, team huddles have been shown to help improve team communication and performance (Glymph et al. 2015, Kellish et al. 2015, Martin et al. 2015, Rodriguez et al. 2015, Donnelly et al. 2016), efficiency of care (Hughes Driscoll & El Metwally 2014, Jain et al. 2015) and staff satisfaction (Martin et al. 2015, Jain et al. 2015). However, the implementation of team huddles is not always effective (e.g. Whyte et al. 2009, Townsend et al. 2017), which may be explained by different strategies used by change leaders to implement and institutionalize this practice. The implementation literature often sparsely describes the strategies used and the subsequent process, which limits our understanding of how to implement team huddles effectively (Proctor et al. 2013). Kotter’s model of change offers a framework for examining the implementation process, which could provide evidence to guide future implementation of new practices in healthcare.

Kotter model of change

Kotter (1996) depicts the change process as a series of eight steps that change leaders should follow to implement and institutionalize changes. Change leaders should: (1) establish a sense of urgency for change, (2) create a guiding coalition, (3) develop a vision and strategy, (4) communicate the change vision, (5) empower broad-based action, (6) generate short-term wins, (7) consolidate gains and produce more change, and (8) anchor the new approaches in the culture (Kotter, 1996). Kotter emphasizes that each step builds on the previous steps, and while skipping steps may create a sense of quick progress, it undermines the likelihood of success down the road. In their subsequent work, Kotter and Cohen proposed that there are three overarching phases in the model: Phase I (steps 1–3) is creating a climate for change, Phase II (steps 4–6) is engaging and enabling the whole organization, and Phase III (steps 7–8) is implementing and sustaining change (Kotter & Cohen 2002, Cohen 2005).

The Kotter model has been used to guide change efforts in diverse healthcare settings, including implementation of a heart-failure disease management system in skilled nursing facilities (Dolansky et al. 2013), expansion of a neurological intensive care unit (Braungardt & Dought 2008), and implementation of nursing bedside handoffs in an orthopedic trauma surgery unit (Casey et al. 2016). It has also been used to guide dissemination of a trauma computerized tomography protocol among emergency departments in Wales (Maclean & Vannet 2016) and a neonatal intensive care unit quality improvement campaign in a large US neonatal network (Ellsbury et al. 2016). Changes reported in these studies were successful, and the Kotter model was viewed a useful implementation guide. However, there is no consensus on which steps are important for ensuring change success. For example, while Ellsbury and colleagues (2016) found that establishing a sense of urgency was key, Dolansky and colleagues (2013) found it hard to sustain the sense of urgency throughout the duration of the study, due to competing demands for staff time. They also found that empowering action and anchoring the change in the culture were challenging (Dolansky et al. 2013).

Furthermore, a review of the organizational change literature found that empirical findings generally supported the individual steps in Kotter’s model; however, the model remained under-investigated as a whole (Appelbaum et al. 2012). We built on the literature and investigated the model as a whole in a sample of eight hospitals implementing team huddles. More specifically, we examined how well the model describes the actual implementation process at these hospitals and whether the execution of early phases influenced execution of subsequent phases (i.e. sustainment of the change), as the model proposes (Kotter 1996). Based on the theory, our proposition is that hospitals performing well on the initial phases will perform well on subsequent phases and will successfully implement team huddles, while hospitals that perform poorly on the initial phases (e.g., skipped steps) will fail in their implementation.

METHODS

Study setting and TeamSTEPPS description

This study was based on an evaluation of TeamSTEPPS implementation in small rural hospitals in Iowa. TeamSTEPPS is a comprehensive patient safety program developed by the US Department of Defense and the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) based on the literature on teamwork, team training, and culture change (King et al. 2008). TeamSTEPPS comprises of teamwork and communication tools (including team huddles) and incorporates the Kotter model to guide implementation (AHRQ, 2014a). AHRQ has been disseminating TeamSTEPPS throughout the US where hospital teams attend offsite training and then return to implement the program at their hospitals. TeamSTEPPS is a customizable program and hospitals had the full autonomy in developing their own implementation objectives (what tools to implement) and strategies (how to implement). This enabled us to study the variation in implementation processes as they unfolded in natural settings, without influence from our team.

Research design and sample

We used a longitudinal prospective qualitative design. We recruited 17 small rural hospitals from Iowa that attended TeamSTEPPS training in 2011, 2012 and 2013 through Iowa’s Quality Improvement Organization. To minimize variation in implementing different tools and focus on differences in implementation processes, we limited the analytic sample to eight hospitals that implemented team huddles, the most commonly implemented tool in the sample hospitals. All eight hospitals included in our analysis were 25-bed rural, critical access hospitals, affiliated with one of the four large health systems operating in Iowa. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol that incorporated appropriate steps to assure protection of human subjects and ethical research practices.

Data collection

After recruiting the hospitals at the initial training, we conducted quarterly site visits to each hospital for two years. Experienced members of our research team conducted semi-structured interviews with key informants, and asked about TeamSTEPPS implementation goals, activities, progress, and other factors influencing the implementation efforts. After obtaining verbal consent, the interviews were recorded, transcribed, and anonymized before the analyses. At these eight hospitals, we conducted 169 interviews with 47 key informants, primarily consisting of executive sponsors and change team members that attended the initial training. Additional interviewees included other executives, middle managers, and frontline staff involved in the implementation. About 80% of the key informants were nurses or had a nursing background.

Coding

Four student coders first read the book Our Iceberg Is Melting (Kotter & Rathgeber 2006), which explained the Kotter model and was part of the training curriculum for the TeamSTEPPS change teams. To ensure a shared understanding of the Kotter model and strengthen coding validity, the coders met with the investigators and discussed how the eight steps in the model might manifest in the implementation of team huddles.

The coders then independently read the transcripts (two coders per hospital) and highlighted any text pertaining to implementation of huddles. They coded the highlighted text into a spreadsheet, using the eight steps of the Kotter model as a coding template. To strengthen coding reliability, all four coders then independently evaluated the fit between the coded text and the steps in Kotter’s model. Any discrepancies among coders were discussed in a group meeting until agreement was reached.

Scoring

We scored hospitals on their performance in each phase of the model (i.e. how well they executed the steps in each phase) to examine the proposition that performance on early phases influences performance on subsequent phases. We scored hospital performance at the level of phases for two reasons. First, the implementation processes largely followed the sequence of the three phases, while the steps within each phase tended to occur iteratively. Second, assessing their performance at the phase level facilitated cross-case analyses of performance patterns. Based on our examination of the coded data, we developed a scoring guide with guiding questions (shown in Table 1) in order to ensure the scores reflected the underlying steps of each phase, and to help with scoring consistency between different coders.

Table 1:

Kotter Model Scoring Guide for Implementation of Team Huddles

| Kotter model steps | Guiding questions for scoring implementation phases |

|---|---|

Phase I

|

|

Phase II

|

|

Phase III

|

|

Two coders independently scored each hospital on their performance in the three phases of the Kotter model, using the following scale: 1 = steps in the phase were not executed or were executed poorly; 2 = most steps in the phase were executed, but none was executed well; 3 = most or all steps in the phase were executed, and some were executed well and some poorly; 4 = all steps in the phase were executed, and most (but not all) were executed well; 5 = all steps in the phase were executed well. Differences in scores were reconciled in group meetings until agreement was reached.

Analyses

To illustrate variation in how well the hospitals executed different steps in the Kotter model, we identified examples of well- and poorly-executed steps. To test the proposition that hospitals with well-executed initial phases will perform better on subsequent phases, we examined hospitals’ score patterns across the three phases. Score patterns where scores did not change by more than 1 point (on a 5-point scale) across the three phases were deemed congruent with the model. Score patterns where scores changed by 2 points or more across the three phases were deemed incongruent with the model. The 2-point threshold strengthened our confidence that changes in scores represented changes in performance, and also better reflected our substantive knowledge of the cases. To help explain the score patterns incongruent with the model, we conducted qualitative case-by-case comparisons (Gibbs 2007) to examine what was unique about these hospitals.

RESULTS

The eight hospitals in our sample varied substantially on how well they executed individual steps in the Kotter model. Table 2 shows examples of hospitals that illustrate well- and poorly-executed steps. Hospital A was a particularly clear case of a success story, and their implementation process most closely followed the Kotter model.

Table 2:

Examples of well- and poorly-executed steps of the Kotter model in hospitals implementing team huddles

| Well Executed Steps | Poorly Executed Steps |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Establishing a sense of urgency | |

|

Hospital A used their AHRQ HSOPS survey data to identify problem areas (teamwork and communication) as perceived by staff, and supplemented the survey results with anecdotal evidence to pinpoint the issues. Hospital F also based their rationale for huddles on their HSOPS survey results and identified specific issues to address in the ED department, their pilot site. |

Hospital B implemented huddles because their hospital system promoted them. However, the change team did not identify any particular issues that huddles were supposed to address. Hospital H did not have a clear rationale for implementing huddles. They were generally trying to “improve communication,” but did not specify any concrete issues to address. |

| Step 2: Creating a guiding coalition | |

|

Hospital A’s change team was fully engaged, and each of them served as a coach for the units implementing huddles. Hospital E assembled a nursing-focused team that could facilitate the implementation in nursing. A Med-Surg nurse was particularly active and led the implementation team. |

Hospitals B did not have anyone committed to implementing huddles, but the CEO formally led the effort. When he later left the hospital, no one else stepped in. Hospital H did not have a team. The OR Assistant Manager led the implementation by herself. |

| Step 3: Developing a vision and strategy | |

|

Hospital A developed a clear vision to use huddles hospital-wide. They strategized to start at the Lab, then spread to other clinical and non-clinical units, and finally institute hospital-wide manager huddles. Hospital F also envisioned all units would use the huddles and planned to implement them at a different unit each month. |

Hospital B only had a general idea to “implement TeamSTEPPS,” and never developed a vision or a plan for huddles. Hospital D initially launched straight into implementation, without a vision or plan. They later had to backtrack and develop a more coherent plan with a timeline. |

| Step 4: Communicating the change vision | |

|

Hospital A emphasized huddles during staff training and, just prior to implementation at each site, they did a short “refresher training” specifically on huddles. Hospital G used several strategies to communicate including training, newsletters, and skills fair. They emphasized their goals and explained why they were implementing huddles. |

Hospital C trained the unit managers and tasked them with implementing huddles. They informed the unit staff about the huddles during huddles at their respective units. Hospital E only communicated about TeamSTEPPS in general and did not explain why they chose to implement huddles or how they would help. |

| Step 5: Empowering broad-based action | |

|

Hospital A first empowered unit managers to support and lead huddles, and then later engaged unit staff. Towards the end, the staff sometimes even lead the huddles themselves. Hospital G trained and empowered clinical leaders to lead huddles. In turn, they engaged their staff, who reportedly felt empowered by the huddles. |

Hospital B change team wanted to empower the charge nurses to lead huddles, but one staff nurse from the change team ended up leading most huddles herself. Hospital E instructed the charge nurses to lead the huddles. However, the team had to hold them accountable and regularly attend the huddles to make sure they did not stop. |

| Step 6: Generating short-term wins | |

|

Hospital A, in order to generate enthusiasm, picked lab as a pilot unit because they were small (“small department, small win”). They thought nursing was too big of a unit to provide an early win. Hospital F started the implementation in the ED department, whose manager was on the change team and championed the huddles, which generated a big win early on. |

Hospitals B started the implementation in nursing, reasoning that if it can work in nursing, it can work anywhere. They did not generate any short-term wins. Hospital C picked Med-Surg as the first implementation site. They tried to start slow and develop the huddles, but failed to generate short terms wins and enough enthusiasm to sustain their efforts. |

| Step 7: Consolidating gains and producing more change | |

|

Hospital A spread the huddles from the lab to the other units, as planned. They used several strategies to monitor progress, including log sheets, surveys, and staff feedback. Hospital D used a combination of audits and staff feedback to monitor progress and make necessary changes to the process. |

Hospital C had some initial success, but could not sustain their efforts. They also failed to monitor their progress adequately. Hospital F failed to build on the momentum from their early win in the ED. Despite their plans for hospital-wide huddles, they only spread them to one other unit. |

| Step 8: Anchoring new approaches in the culture | |

|

Hospital A reported at the end of our study that all departments were huddling regularly, though some issues in nursing remained. They said huddles were their first true success, where they became part of the daily routine. Hospital D managed to “hardwire” huddles in their Med-Surg unit along with bedside shift reports (they implemented both tools simultaneously) |

Hospital B did not institutionalize huddles in any of their units and suspended implementation activities after the CEO left. Hospital C had limited success in two units, but the huddles did not become part of the routine by the end of our study. They identified one problem was that huddles were not a priority. |

Notes: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; HSOPS = Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture; ED = Emergency Department; Med-Surg = Medical-Surgical Unit

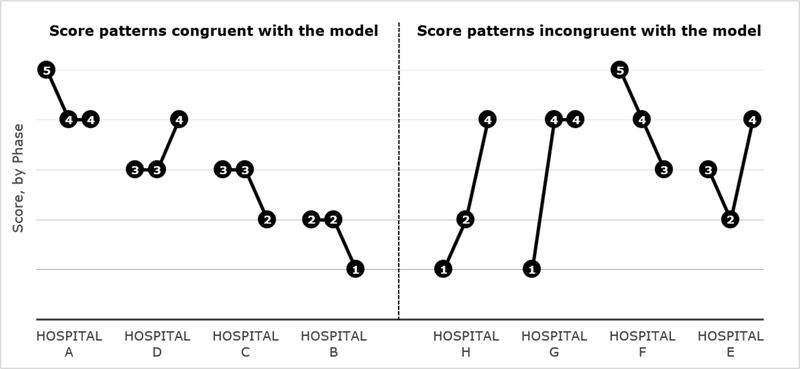

The eight hospitals exhibited varied score patterns (Figure 1). Four of the eight hospitals (Hospitals A, D, C, and B) had score patterns congruent with the Kotter model, with consistently high or low scores across phases (i.e. scores did not change by more than one point). This supported our proposition that executing the initial steps well (Phase I – creating a change climate) will lead to a sustained effect in subsequent phases in the change process, and that executing the initial steps poorly will undermine the performance in subsequent phases.

Figure 1:

Hospital score patterns for the three phases of the Kotter model

The other hospitals had score patterns incongruent with the Kotter model, with substantial changes in scores across phases (i.e. scores changed by two points or more). Hospitals E, G and H performed well in the last phase despite performing poorly in the first or second phase, and Hospital F performed poorly in the last phase despite performing well in the first phase. These score patterns did not support our proposition.

After qualitatively re-examining our data on the four hospitals whose score patterns were incongruent with the Kotter model, we identified key factors that helped illuminate their varied performance across the three phases.

Hospital F had a committed team and a clear champion for huddles (ED manager), as well as a detailed plan for the rollout across different units. However, they clearly articulated the need for huddles only for the ED, their pilot site. Lacking a clear sense of urgency to spread huddles to other units, they ultimately only succeeded in their implementation in the ED.

Hospital E had a nursing-centered team, with a clear focus on implementing huddles in their nursing department. They did not have any short-term wins, nor did they communicate and empower much of their nursing staff. Instead, they seem to have relied on a combination of persistence, enforcement and accountability. Team members led the huddles and, over time, the nursing staff started seeing the value in huddles and appreciated the improved communication and teamwork on their unit.

Hospital H was unique in that the change effort was led by one person, the OR assistant manager. She combined huddles with Lean process improvement and simply began huddling regularly. The process unfolded with subtle pressure and persistence from the OR manager – for example, attending huddles was included in staff annual evaluations. Over time, the OR staff began contributing and engaging in huddles. By the end of our study, the huddles became part of the daily routine.

Hospital G team never clearly established a need for huddles, were not committed to their implementation, and did not have any vision or concrete plan for the rollout. However, they began experimenting with huddles in their Lab (the lab manager was on the change team) to learn in a small, more controlled environment. About the same time, they trained all unit managers on TeamSTEPPS, and encouraged them to implement TeamSTEPPS tools in their units as they saw fit. Over time, huddles spread from the lab, first to the clinic (the lab manager was also the clinic manager at the time) and then to several other units.

These cases illustrate the importance of implementation scope and the strategies or approaches change teams adopt. The differences were rooted in the first step (establishing a sense of urgency), where the hospitals differed in terms of scope (implementing huddles in individual unit vs multiple units) and how strong the sense of urgency was at each targeted unit. Hospital F had a broad scope, but the sense of urgency (a clear need for huddles) was only established in the pilot unit, which inhibited the spread. Hospitals E and H similarly did not have a clear sense of urgency, but focused implementation on individual units, enabling the change team to persist until the benefits of huddles were more tangible. Finally, Hospital G had neither the sense of urgency nor a defined scope, but allowed the huddles to diffuse more naturally to where several units ultimately adopted and used them.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we examined how well the Kotter model of change applies to the implementation of team huddles in eight critical access hospitals in Iowa. Hospitals varied in their performance in the different phases of change where half of the hospitals performed consistently well or poorly across the phases, supporting our proposition that early performance facilitates or hinders subsequent performance. The other half of the hospitals, however, varied more substantially on their performance across phases and different factors explained their score patterns.

The findings provide some support for the Kotter model, where it explained the change patterns in half of the hospitals. As the model proposes, the foundation for the implementation is provided during the early steps, particularly in establishing a sense of urgency (why they needed to implement huddles) and forming a guiding coalition (a team committed to implementing huddles). The first step was previously identified as the critical point in change management (e.g. Kotter 2008, Ellsbury et al. 2016). Similarly, the organizational change readiness theory proposes a shared change commitment positively influences change processes, where key stakeholders may commit to change implementation for various reasons (Weiner, 2009). This is illustrated by the case of Hospital F, which only established a sense of urgency for the pilot unit. They failed to spread huddles to other units where different priorities undermined the commitment to implement huddles. The implementation literature is also beginning to recognize the role change teams play in implementation processes (Lessard et al. 2016, Zhu et al. 2016). Having a committed change team helps ensure they dedicate their attention to the implementation over the span of the entire process. This may be particularly important in small rural hospitals and other organizations with time and resource constraints (Paez et al. 2013), where change activities are often added to the daily workload of managers and staff.

The other cases suggest that implementation strategies may deviate from the Kotter model, where skipping or performing poorly on earlier steps does not necessarily compromise the progress of the implementation. In two cases, change teams succeeded by focusing their implementation in one unit, persisting and enforcing huddles until staff recognized their value. Another change team employed a rather hands-off approach, relying more on communication and empowerment, and delegating the implementation decisions to department and unit leaders. These findings highlight the importance of considering the scope of the implementation, where other factors may drive processes when the scope is narrow (single unit implementation) or not defined (diffused implementation). However, it remains unclear what factors influence the effectiveness of such strategies.

While process models such as Kotter’s provide a useful implementation guide, they typically do not consider contextual factors prominent in other implementation models (Nilsen, 2015). For example, Harvey and Kitson (2016) propose that multiple factors, including organizational and innovation characteristics, interact with change activities (i.e. facilitation), influencing how processes unfold. Using this framework, we considered how characteristics of huddles help explain our findings. Huddles improve communication, which can, in turn, strengthen initial implementation and contribute to sustainment. In hospitals that followed the Kotter model, improved communication may have reinforced the early steps, facilitating the spread and sustained use of the huddles in the last phase, as the model proposes. In hospitals where huddles were initially more enforced, improved communication may have improved staff buy-in, leading to even more effective communication and staff buy-in. This was made possible by enforceability of huddles, where change leaders could persist in their use until staff buy-in developed. In contrast, tools that are used at the discretion of staff (e.g. handoffs) are harder to enforce, which necessitates obtaining staff buy-in early on.

Limitations

Our findings need to be interpreted in light of certain limitations of our study design. First, we relied on self-reported data obtained in the interviews, where recall bias may have influenced our findings. To help overcome this bias, we interviewed multiple key informants at each hospital, enabling us to triangulate data across different sources. We also conducted the interviews quarterly, allowing us to minimize recall bias over the two-year study period. Nevertheless, certain activities that took place may have been omitted in the interviews, which would have given us a partial picture of how steps in the Kotter model were executed.

Second, we do not have objective outcome data to help us establish the success of each hospital’s implementation. We relied on the change teams’ perception of success, but the different hospitals and units may have varied in fidelity and effectiveness of their huddles. Furthermore, we do not know how well different hospitals sustained the use of huddles beyond the two years, limiting our ability to assess how different change processes relate to long-term change sustainment.

Finally, our sample included only small rural hospitals, limiting our ability to generalize our findings to other settings. However, these hospitals tend to be understudied, and our study makes an important contribution to the literature on implementing change in these resource-constrained hospitals.

Conclusion

Our findings provide partial support for Kotter’s change model, which applies better in cases where change implementation scope involves multiples units. Where implementation scope is narrower, other strategies can be effective. Future research needs to examine what conditions are required for these approaches to produce desirable outcomes.

IMPLICATION FOR NURSING MANAGEMENT

Implementing evidence-based practices to improve patient safety and outcomes is a sine qua non for high performance in healthcare. Team huddles enhance patient safety by improving team communication and performance (Goldenhar et al. 2013, Glymph et al. 2015), but are not always implemented successfully (Whyte et al. 2009, Townsend et al. 2017). In this study, we found that Kotter’s model, a popular change management tool, can be a useful implementation guide, particularly when the scope is to implement changes in multiple units.

As the model proposes, our findings indicate that change leaders need to first clearly establish the need for change and create a sense of urgency. Most effective leaders analyzed data to identify high-priority performance gaps and then selected huddles to address them. This helped them articulate their vision for how huddles can contribute to patient care, providing the foundation to effectively communicate for change and empower unit leaders and staff to use huddles. Savvy leaders also piloted the huddles in particularly receptive units, generating early wins and creating more enthusiasm for change. This helped spread the huddles to other units and ensure huddling became part of the hospital culture. On the other hand, ineffective leaders decided to implement huddles without articulating their reasons. Lacking a compelling vision to communicate, they failed to empower action and faced considerable resistance to change, leading to only limited and short-term success, or none at all. Examples of well- and poorly-executed steps in the Kotter model are provided in Table 2.

Kotter’s model is not without limitations. We found that sometimes hospitals skipped steps and still achieved good results, but the model failed to explain why or how. Furthermore, Kotter’s model provides only limited guidance on what it takes to execute its steps well. Other implementation models can complement the use of the Kotter model. One popular model is PARIHS, which identifies a variety of factors influencing implementation, including facilitation activities that change leaders (i.e. facilitators) can employ (Harvey & Kitson, 2016). Using different kinds of models in tandem provides change leaders with a more comprehensive toolset to guide and facilitate the changes, helping avoid the limitations and blind spots of individual models.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Adrianne Butcher, Erik Jorgensen, Michelle Martin, Nabil Natafgi, Madhana Pandian, Abby Powel, Jill Scott-Cawiezell, Greg Stewart, Consuelo Valladolid, Tom Vaughn, and Kelli Vellinga for contributing to the research project.

Funding: This research was supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ; R18HS018396 and R03HS024112). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval of Research: The research was reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB ID#: 201109734).

Contributor Information

Jure Baloh, Dept. of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa.

Xi Zhu, Dept. of Health Management and Policy, University of Iowa.

Marcia M. Ward, Dept. of Health Management and Policy, University of Iowa.

REFERENCES

- American College of Healthcare Executives (2016) Survey: Healthcare Finance, Safety and Quality Cited by CEOs as Top Issues Confronting Hospitals in 2015. Available at https://www.ache.org/pubs/Releases/2016/top-issues-confronting-hospitals-2015.cfm, accessed January 29, 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014a) TeamSTEPPS 2.0: Module 8. Change Management. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/fundamentals/module8/igchangemgmt.html, accessed September 25, 2015.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014b) TeamSTEPPS Pocket Guide. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html, accessed October 19, 2016.

- Appelbaum SH, Habashy S, Malo J, & Shafiq H. (2012) Back to the future: revisiting Kotter’s 1996 change model. Journal of Management Development 31(8), 764–782. DOI: 10.1108/02621711211253231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braungardt T & Fought SG (2008) Leading change during an inpatient critical care unit expansion. Journal of Nursing Administration 38(11), 461–167. DOI: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000339476.73090.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DS (2005). The Heart of Change Field Guide: Tools and Tactics For Leading Change in Your Organization. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- Dolansky MA, Hitch JA, Piña IL & Boxer RS (2013) Improving heart failure disease management in skilled nursing facilities: lessons learned. Clinical Nursing Research 22(4), 432–447. DOI: 10.1177/1054773813485088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly LF (2016) Daily readiness huddles in radiology – improving communication, coordination, and problem-solving reliability. Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology 46(2), 86–90. DOI: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsbury DL, Clark RH, Ursprung R, Handler DL, Dodd ED &Spitzer AR (2016) A multifaceted approach to improving outcomes in the NICU: the Pediatrix 100.000 babies campaign. Pediatrics 137(4). DOI: 10.1542/peds.2015-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs GR (2007) Analyzing Qualitative Data. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Glymph DC, Olenick M, Barbera S, Brown EL, Prestianni L & Miller C (2015) Healthcare utilizing deliberate discussion linking events (HUDDLE): a systematic review. AANA Journal 83(3),183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenhar LM, Brady PW, Sutcliffe KM & Muething SE (2013) Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. BMJ Quality & Safety 22(11), 899–906. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G & Kitson A (2016) PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science, 11(33). DOI: 10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Driscoll C & El Metwally D (2014) A daily huddle facilitates patient transports from a neonatal intensive care unit. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports 3(1). DOI: 10.1136/bmjquality.u204253.w1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain AL, Jones KC, Simon J & Patterson MD (2015) The impact of a daily pre-operative surgical huddle on interruptions, delays, and surgeon satisfaction in an orthopedic operating room: a prospective study. Patient Safety in Surgery 9(8). DOI: 10.1186/s13037-015-0057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellish AA, Smith-Miller C, Ashton K & Rodgers C (2015) Team huddle implementation in a general pediatric clinic. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development. 31(6), 324–327. DOI: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King HB, Battles J, Baker DP, Alonso A, Salas E, Webster J, Toomey L & Salisbury M (2008) TeamSTEPPS™: team strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety In Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Henriksen K, Battles J, Keyes M, Grady M eds). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP (1996) Leading Change. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP (2008) A Sense of Urgency. Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP & Cohen DS (2002) The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP & Rathgeber H (2006) Our Iceberg Is Melting: Changing and Succeeding Under Any Conditions. St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- Lessard S, Bareil C, Lalonde L, Duhamel F, Hudon E, Goudreau J & Lévesque L (2016) External facilitators and interprofessional facilitation teams: a qualitative study of their roles in supporting practice change. Implementation Science, 11(97). DOI: 10.1186/s13012-016-0458-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean DF & Vannet N (2016) Improving trauma imaging in Wales through Kotter’s theory of change. Clinical Radiology 71(5), 427–431. DOI: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HA & Ciurzynski SM (2015) Situation, background, assessment, and recommendation-guided huddles improve communication and teamwork in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing 41(6), 484–488. DOI: 10.1016/j.jen.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P (2015) Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science 10(53). DOI: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez K, Schur C, Zhao L & Lucado J (2012) A national study of nurse leadership and supports for quality improvement in rural hospitals. American Journal of Medical Quality 28(2), 127–134. DOI: 10.1177/1062860612451851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parand A, Dopson S, Renz A & Vincent C (2014) The role of hospital managers in quality and patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open 4(9). DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Powell BJ & McMillen JC (2013) Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science 8(139). DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost SM, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, McDaniel RR Jr. & Pugh J (2015) Health care huddles: managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Management Review 40(1), 2–12. DOI: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez HP, Meredith LS, Hamilton AB, Yano EM & Rubenstein L (2015) Huddle up! The adoption and use of structured team communication for VA medical home implementation. Health Care Management Review 40(4), 286–299. DOI: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small A, Gist D, Souza D, Dalton J, Magny-Normilus C & David D (2016) Using Kotter’s change model for implementing bedside handoff: a quality improvement project. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 31(4), 304–309. DOI: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler CB, Ritchie JA, Rycroft-Malone J & Charns MP (2014) Leadership for evidence-based practice: strategic and functional behaviors for institutionalizing EBP. Worldviews on Evidence Based Nursing. 11(4). 219–226. DOI: 10.1111/wvn.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission (2015) Sentinel Event Data - Root Causes by Event Type. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_statistics/, accessed Oct 23, 2015.

- Townsend CS, McNulty M & Grillo-Peck A (2017) Implementing huddles improves care coordination in an academic health center. Professional Case Management 22(1), 29–35. DOI: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ (2009) A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science 4(67). DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte S, Cartmill C, Gardezi F, Reznick R, Orser BA, Doran D & Lingard L (2009) Uptake of a team briefing in the operating theatre: a Burkean dramatistic analysis. Social Science & Medicine 69(12), 1757–1766. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Kuzel AJ, Dovey SM & Phillips RL Jr. (2004). A string of mistakes: the importance of cascade analysis in describing, counting, and preventing medical errors. The Annals of Family Medicine 2(4), 317–326. DOI: 10.1370/afm.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Baloh J, Ward MM & Stewart GL (2016) Deliberation makes a difference: preparation strategies for TeamSTEPPS implementation in small and rural hospitals. Medical Care Research & Review 73(3), 283–307. DOI: 10.1177/1077558715607349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]