Abstract

Objective:

Studies have documented greater risk for heavy marijuana use and consequences among adolescents and young adults who have acquired medical marijuana cards. With the cards, they are enrolled in their state’s medical marijuana program and granted access to medical marijuana dispensaries. It is unknown, however, what factors influence young people to acquire medical marijuana cards, such as whether they seek out medical marijuana cards for the mental and physical health concerns that marijuana is targeted to address or whether they seek out medical marijuana cards solely because they are heavier users.

Method:

There were 264 participants (54% female) in the current study, which used longitudinal data (Time 1 and Time 2, 1 year later) to compare young adult marijuana users who did not have a medical marijuana card at either time point (n = 215) with marijuana users who reported acquiring a medical marijuana card by Time 2 (n = 49; 19% of the sample). We used logistic regression to predict participants’ acquisition of a medical marijuana card at Time 2 from Time 1 demographic factors, mental health symptoms of anxiety and depression, reports of poor physical health and symptoms, and frequency of use.

Results:

Analyses indicated that young adults who were male (odds ratio = 2.91) and who reported more frequent marijuana use (odds ratio = 1.07) were at greater odds of acquiring a medical marijuana card over the study period. None of the mental or physical health concerns predicted card acquisition.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that more frequent use, not necessarily mental and physical health concerns, is a main influence on medical marijuana card acquisition.

In the united states, the cultivation and distribution of marijuana for medical purposes is currently legal in 33 states and the District of Columbia. In many of these states, “medical marijuana cards” are issued to residents who receive a recommendation from a licensed provider to use medical marijuana for presenting physical and/or mental health concerns. One benefit of acquiring a medical marijuana card is that a resident of a certain age (varies by state) with a card can enter and purchase marijuana at medical dispensaries throughout the state. For states that have also approved the sale and growth of recreational marijuana by those 21 and older, there may still be benefits to obtaining a medical marijuana card. For example, in California, where cultivation and distribution of recreational marijuana was legalized by voters in November 2016, the drug was not available for purchase in recreational marijuana outlets until January 2018, making medical dispensaries the only legal outlets from which to obtain marijuana. In addition, even after recreational marijuana dispensaries began opening and marijuana was available to anyone 21 and older, the benefits of having of card included not needing to be 21 to purchase marijuana at medical dispensaries and being able to purchase marijuana that is not subjected to California state sales tax.

Qualifying conditions for medical marijuana cards differ by state, and the medicinal benefits of marijuana are becoming better understood through empirical research. There is substantial evidence to support its benefits in reducing chronic pain, alleviating chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, improving spasticity symptoms among patients with multiple sclerosis, and improving short-term sleep outcomes among those with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2017). However, there is also substantial evidence for harms of marijuana, such as worsening respiratory symptoms, increased risk of motor vehicle accidents, lower birth rates, and increased risk for developing psychotic disorders (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2017). Moreover, early initiation of marijuana use, as well as increases in frequency of use during adolescence, are risk factors for the development of problematic marijuana and other substance use, cognitive difficulties, and mental health problems later in life (Cairns et al., 2014; Crean et al., 2011; Macleod et al., 2004; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2017).

Recent studies suggest that young people who obtain medical marijuana cards may be at increased risk for concurrent heavy and problem use (Boyd et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2019). For example, cross-sectional data from high school seniors who were part of the national Monitoring the Future Study showed that those who reported obtaining marijuana through their state’s medical marijuana programs also reported more frequent use and were more likely to report daily use and “being hooked” on marijuana compared with those who obtained marijuana from a nonmedical source (Boyd et al., 2015). Using longitudinal data over 7 years, we found that young adults (Mage = 19) who reported having a medical marijuana card were more likely than those users without a medical marijuana card to report marijuana negative consequences, selling marijuana, and driving under the influence of marijuana in the past year (Tucker et al., 2019). Further, those with a medical marijuana card reported a history of heavier use throughout adolescence compared with non–medical marijuana card holders. However, this study was not able to discern temporal effects based on when an individual had acquired a medical marijuana card; rather, the study examined use and problems related to whether one had a medical marijuana card at all during some point of adolescence. In addition, this prior analysis was not designed to address whether obtaining a medical marijuana card in young adulthood is primarily driven by one’s heaviness of use, rather than by the physical or mental health problems card acquisition is ostensibly obtained to address. The answer to this question is key, because it has important policy implications as states design their own medical marijuana card programs.

Present study

The current longitudinal study focuses on young adults in California who initially reported past-month marijuana use but did not have a medical marijuana card and compares those who did and those who did not obtain a card over a 1-year period on demographics, physical and mental health, and heaviness of marijuana use. Data were collected between 2015 and 2017, when medical marijuana was available for possession and sale in California, but before the opening of recreational marijuana outlets in January 2018. Despite changes in recreational marijuana laws during our study period, all youth in the study were under 21 during data collection periods; thus, they were not legally able to purchase marijuana without a medical marijuana card during the study period. Because of this, we hypothesized that acquiring a medical marijuana card would be driven primarily by use, such that youth with more frequent use would seek out medical marijuana cards over and above demographic factors or the physical and mental health factors that the medical marijuana cards are intended to address.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants came from two waves of a larger multiwave study of substance use among adolescents and young adults.

Participants were initially recruited in sixth/seventh grades (ages 11–13 years) for a substance use prevention program study conducted in 16 middle schools in southern California in 2008 (D’Amico et al., 2012). Participants completed five surveys in middle school classrooms, and after eighth grade they completed online surveys through age 18 to 20. Parents initially gave consent for participation, but at age 18, participants were re-consented and agreed to complete annual online surveys. All study procedures were approved by the RAND Institutional Review Board. Further details of recruitment and retention rates across waves, including how response rates between survey waves ranged from 74% to 90%, and how attrition was not associated with demographic or substance use, are described in detail elsewhere (D’Amico et al., 2016, 2018; Dunbar et al., 2019). Data for this study come from online surveys completed at Wave 8 (Time 1; N = 2,511) and Wave 9 (Time 2; n = 2,431); 89% of participants who completed Wave 8 also completed Wave 9.

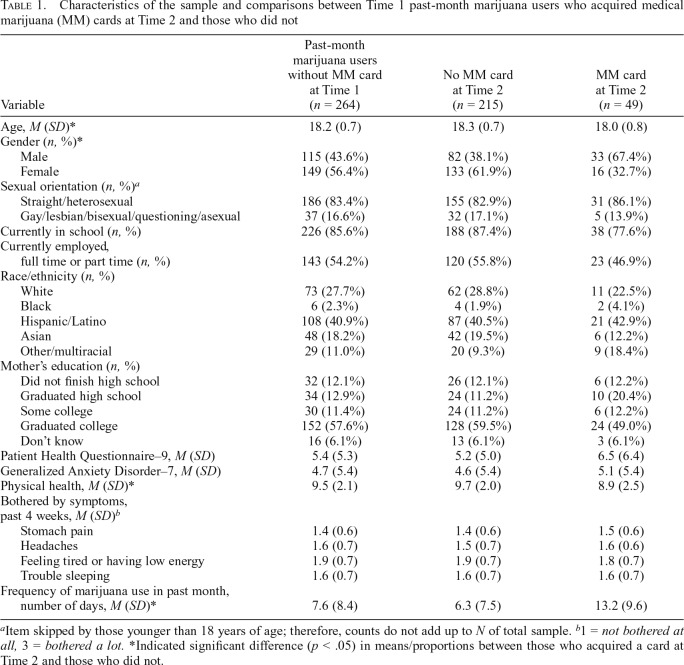

The analytic sample for this study consisted of 264 young adult participants who reported any use of marijuana in the past month at Time 1, did not have a medical card at Time 1, and completed the measure of marijuana card status at Time 2. We restricted the analytic sample to participants who lived in California and were under 21. Most participants were excluded from analyses because of no past-month use at Time 1. Sample characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample and comparisons between Time 1 past-month marijuana users who acquired medical marijuana (MM) cards at Time 2 and those who did not

| Variable | Past-month marijuana users without MM card at Time 1 (n = 264) | No MM card at Time 2 (n = 215) | MM card at Time 2 (n = 49) |

| Age, M (SD)* | 18.2 (0.7) | 18.3 (0.7) | 18.0 (0.8) |

| Gender (n, %)* | |||

| Male | 115 (43.6%) | 82 (38.1%) | 33 (67.4%) |

| Female | 149 (56.4%) | 133 (61.9%) | 16 (32.7%) |

| Sexual orientation (n, %)a | |||

| Straight/heterosexual | 186 (83.4%) | 155 (82.9%) | 31 (86.1%) |

| Gay/lesbian/bisexual/questioning/asexual | 37 (16.6%) | 32 (17.1%) | 5 (13.9%) |

| Currently in school (n, %) | 226 (85.6%) | 188 (87.4%) | 38 (77.6%) |

| Currently employed, full time or part time (n, %) | 143 (54.2%) | 120 (55.8%) | 23 (46.9%) |

| Race/ethnicity (n, %) | |||

| White | 73 (27.7%) | 62 (28.8%) | 11 (22.5%) |

| Black | 6 (2.3%) | 4 (1.9%) | 2 (4.1%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 108 (40.9%) | 87 (40.5%) | 21 (42.9%) |

| Asian | 48 (18.2%) | 42 (19.5%) | 6 (12.2%) |

| Other/multiracial | 29 (11.0%) | 20 (9.3%) | 9 (18.4%) |

| Mother’s education (n, %) | |||

| Did not finish high school | 32 (12.1%) | 26 (12.1%) | 6 (12.2%) |

| Graduated high school | 34 (12.9%) | 24 (11.2%) | 10 (20.4%) |

| Some college | 30 (11.4%) | 24 (11.2%) | 6 (12.2%) |

| Graduated college | 152 (57.6%) | 128 (59.5%) | 24 (49.0%) |

| Don’t know | 16 (6.1%) | 13 (6.1%) | 3 (6.1%) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire–9, M (SD) | 5.4 (5.3) | 5.2 (5.0) | 6.5 (6.4) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7, M (SD) | 4.7 (5.4) | 4.6 (5.4) | 5.1 (5.4) |

| Physical health, M (SD)* | 9.5 (2.1) | 9.7 (2.0) | 8.9 (2.5) |

| Bothered by symptoms, past 4 weeks, M (SD)b | |||

| Stomach pain | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.6) |

| Headaches | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.6) |

| Feeling tired or having low energy | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.7) |

| Trouble sleeping | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) |

| Frequency of marijuana use in past month, number of days, M (SD)* | 7.6 (8.4) | 6.3 (7.5) | 13.2 (9.6) |

Item skipped by those younger than 18 years of age; therefore, counts do not add up to N of total sample.

1 = not bothered at all, 3 = bothered a lot.

Indicated significant difference (p < .05) in means/proportions between those who acquired a card at Time 2 and those who did not.

Measures

Demographics.

At Time 1, participants reported age, gender (male vs. female), sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity. We assessed mother’s education level as a proxy for family socioeconomic status (Korupp et al., 2002), with college graduate as the reference group. Participants also reported on current school enrollment and employment status.

Medical marijuana card status.

At both Time 1 and Time 2, participants were asked whether they currently had a medical marijuana card (yes/no).

Marijuana use.

At both time points, participants reported on the number of days they used marijuana in the past month (0 = 0 days to 6 = 20–30 days). Response options were recoded to reflect midpoints (e.g., 20–30 days = 25) using an established approach to yield a continuous score ranging from 0 to 25 (Dawson, 2003; Osilla et al., 2014).

Mental health.

Eight depression symptoms (e.g., “feeling, down, depressed or hopeless”) in the past 2 weeks were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., 2009) at Time 1 (α = .90). Seven anxiety symptoms (e.g., “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”) in the past 2 weeks were assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) at Time 1 (α = .94). Items in both scales were rated from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day, and composite scores were created by summing items.

Physical health.

A composite score for physical health at Time 1 was generated from three items: the single item of the General Health factor on the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (Ware et al., 1996) assessing, “In general, would you say your health is …,” with response options ranging from 1 = excellent to 5 = poor, and two items from the PROMIS Pediatric Physical Function Scales (DeWitt et al., 2011) assessing, “In the past month … I have been physically able to do the activities I enjoy most” and “… I could do sports and exercise that other kids my age could do” with response options of 1 = with no trouble to 5 = not able to do. Items were reverse scored so that higher scores reflected better physical health (α = .75). In addition, four items assessed how bothered participants had been by physical ailments/symptoms in the previous 4 weeks (1 = not at all bothered, 2 = bothered a little, 3 = bothered a lot): stomach pain, headaches, feeling tired or having low energy, and trouble sleeping (Kroenke et al., 2002).

Analytic plan

We compared participants who acquired a medical marijuana card at Time 2 with those who did not on demographics, physical health and symptoms, mental health, and frequency of marijuana use using t tests and chi-square comparisons. To test our hypothesis that more frequent use was the primary factor associated with acquiring a medical marijuana card, we conducted a hierarchical logistic regression analysis in which we first entered in demographic factors, followed by mental health, physical health, and marijuana use on four separate steps. We interpreted significant predictors at each step.

Results

Analyses revealed that 19% (n = 49) of the 264 youth who reported past-month marijuana use and did not have a medical marijuana card at Time 1 acquired a medical marijuana card by Time 2. Those who acquired a medical marijuana card were significantly younger, t(262) = 2.41; more likely to be male, χ2(1) = 13.84; and reported worse physical health, t(62) = 2.05, compared with those who did not acquire a medical marijuana card (all ps < .05). Medical marijuana card holders at Time 2 reported using marijuana on more than twice the number of days in the past month as non–card holders, t(62) = -4.71, p < .05 (Table 1).

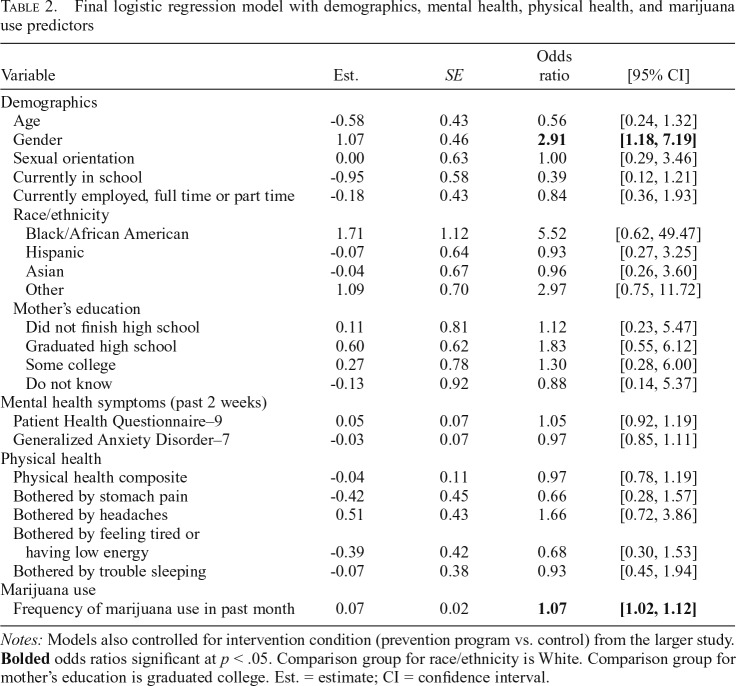

The logistic regression models revealed that on Step 1 (demographics), gender (estimate = 1.22, SE = 0.42) and being in school (estimate = -1.20, SE = 0.51) significantly predicted having a medical marijuana card at Time 2. The odds of acquiring a card at Time 2 were 3.4 times higher for males (95% CI [1.48, 7.78]) and 0.30 times lower for those in school (95% CI [0.11, 0.82]). On Step 2 (adding mental health), neither of the individual scales significantly predicted having a medical marijuana card at Time 2. Both gender (estimate = 1.21, SE = 0.42) and being in school (estimate = -1.17, SE = 0.52) remained significant. In the model on Step 3 (adding physical health), neither the physical health composite nor any of the individual physical health symptoms significantly predicted having a medical marijuana card at Time 2. Both gender (estimate = 1.26, SE = 0.45) and being in school (estimate = -1.23, SE = 0.55) remained significant. On Step 4 (frequency of marijuana use), use was a significant predictor of having a medical marijuana card (estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.02), whereby an increase in one day of use at Time 1 was associated with 1.07 times greater odds (95% CI [1.02, 1.12]) of acquiring a medical marijuana card at Time 2. Gender continued to be significant (estimate = 1.07, SE = 0.46) such that the odds of acquiring a card at Time 2 were 2.9 times greater (95% CI [1.18, 7.19]) for males (Table 2).

Table 2.

Final logistic regression model with demographics, mental health, physical health, and marijuana use predictors

| Variable | Est. | SE | Odds ratio | [95% CI] |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | -0.58 | 0.43 | 0.56 | [0.24, 1.32] |

| Gender | 1.07 | 0.46 | 2.91 | [1.18, 7.19] |

| Sexual orientation | 0.00 | 0.63 | 1.00 | [0.29, 3.46] |

| Currently in school | -0.95 | 0.58 | 0.39 | [0.12, 1.21] |

| Currently employed, full time or part time | -0.18 | 0.43 | 0.84 | [0.36, 1.93] |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black/African American | 1.71 | 1.12 | 5.52 | [0.62, 49.47] |

| Hispanic | -0.07 | 0.64 | 0.93 | [0.27, 3.25] |

| Asian | -0.04 | 0.67 | 0.96 | [0.26, 3.60] |

| Other | 1.09 | 0.70 | 2.97 | [0.75, 11.72] |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| Did not finish high school | 0.11 | 0.81 | 1.12 | [0.23, 5.47] |

| Graduated high school | 0.60 | 0.62 | 1.83 | [0.55, 6.12] |

| Some college | 0.27 | 0.78 | 1.30 | [0.28, 6.00] |

| Do not know | -0.13 | 0.92 | 0.88 | [0.14, 5.37] |

| Mental health symptoms (past 2 weeks) | ||||

| Patient Health Questionnaire–9 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 1.05 | [0.92, 1.19] |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 | -0.03 | 0.07 | 0.97 | [0.85, 1.11] |

| Physical health | ||||

| Physical health composite | -0.04 | 0.11 | 0.97 | [0.78, 1.19] |

| Bothered by stomach pain | -0.42 | 0.45 | 0.66 | [0.28, 1.57] |

| Bothered by headaches | 0.51 | 0.43 | 1.66 | [0.72, 3.86] |

| Bothered by feeling tired or having low energy | -0.39 | 0.42 | 0.68 | [0.30, 1.53] |

| Bothered by trouble sleeping | -0.07 | 0.38 | 0.93 | [0.45, 1.94] |

| Marijuana use | ||||

| Frequency of marijuana use in past month | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.07 | [1.02, 1.12] |

Notes: Models also controlled for intervention condition (prevention program vs. control) from the larger study. Bolded odds ratios significant at p < .05. Comparison group for race/ethnicity is White. Comparison group for mother’s education is graduated college. Est. = estimate; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

As more states consider medical marijuana legalization, it is important to understand factors associated with enrollment in these programs, such as whether enrollment is influenced by demographics, presenting mental and physical health symptoms, or, more simply, by frequency of use. Many individuals, both minors and those 21 and older, struggle with legitimate medical and psychological concerns that can benefit from medical marijuana (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2017). However, making medical marijuana cards easy to obtain for vaguely defined mental or physical health conditions that are not supported by any research evidence has potential for heavier users to claim need for a medical marijuana card solely to have easier access. Indeed, the current findings suggest that frequency of use may be a driving factor influencing young people to acquire a medical marijuana card. After we controlled for demographic factors and multiple mental and physical health factors often associated with obtaining a medical marijuana card, frequency of use was the only predictor (other than male gender, which has been associated with greater rates of marijuana use among young adults; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018; Cuttler et al., 2016; Schepis et al., 2011) of obtaining a medical marijuana card within the next year. Coupled with similar evidence from recent studies showing that youth with medical marijuana cards may be more likely to report heavy and problematic use than youth who use marijuana but have not obtained the drug for medical purposes (Boyd et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2019), these findings can help inform policies for states considering medical marijuana laws. Policymakers are encouraged to review these findings alongside the evidence for marijuana’s medicinal benefits to design medical marijuana programs in their states that allow card acquisition only for people with mental and physical health problems that have documented evidence of medicinal benefit.

Although these findings can help inform medical marijuana policy, there are still gaps that future research can address. First, our online study design did not allow us to probe further and ask participants personal reasons for medical marijuana card acquisition. Qualitative studies and more detailed survey work are needed to assess reasons young people seek out medical marijuana cards specifically, which would advance work conducted on self-reported medical reasons for seeking marijuana (e.g., for relief from chronic pain, sleep problems, and anxiety; Park & Wu, 2017). Nonmedical reasons could be to save money, to have access to more dispensaries, or perceptions that medical marijuana is of higher quality than recreational marijuana. Second, we were limited in the mental and physical health symptoms we assessed, and we did not specifically ask about qualifying conditions for obtaining a medical marijuana card in California, which currently range from AIDS, seizures, and cancer to arthritis, glaucoma, and chronic pain (California Department of Public Health, 2019). Although the generality of our items cuts across many conditions, research is needed in this area. It is important to note, however, that California law specifies that “any other chronic or persistent medical symptom that either substantially limits a person’s ability to conduct one or more of major life activities as defined in the federal Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, or if not alleviated, may cause serious harm to the person’s safety, physical, or mental health” (California Department of Public Health, 2019) can qualify, as long as a provider recommends medical marijuana to the individual. Thus, assessment of the stated qualifying condition might still miss countless other conditions for which California residents may qualify. Still, future research should look more specifically at the condition(s) for which an individual reports using medical marijuana, as it may help provide a better understanding of why people prefer to use medical marijuana over recreational marijuana in states where both are legal, and whether there are certain conditions that are more strongly associated with medical marijuana use. Last, we looked at only two time points, which did not allow us to determine more distal effects of medical marijuana card acquisition. It is important to expand this longitudinal work using both qualitative and quantitative methods to determine how use trajectories change after one acquires a medical marijuana card.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kirsten Becker, Jen Parker, and RAND Survey Research Group for overseeing the school-survey administrations and the web-based surveys.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01AA016577 and R01AA020883 (principal investigator: Elizabeth J. D’Amico).

References

- Boyd C. J., Veliz P. T., McCabe S. E. Adolescents’ use of medical marijuana: A secondary analysis of Monitoring the Future data. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;57:241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.008. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns K. E., Yap M. B. H., Pilkington P. D., Jorm A. F. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;169:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.006. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Public Health. Medical marijuana identification card program: Frequently asked questions. 2019 Retrieved from https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CHSI/Pages/MMICP-FAQs.aspx.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crean R. D., Crane N. A., Mason B. J. An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2011;5:1–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820c23fa. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820c23fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttler C., Mischley L. K., Sexton M. Sex differences in cannabis use and effects: A cross-sectional survey of cannabis users. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2016;1:166–175. doi: 10.1089/can.2016.0010. doi:10.1089/can.2016.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., Green H. D. J., Miles J. N. V., Zhou A. J., Tucker J. A., Shih R. A. Voluntary after school alcohol and drug programs: If you build it right, they will come. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22:571–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00782.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., Rodriguez A., Tucker J. S., Pedersen E. R., Shih R. A. Planting the seed for marijuana use: Changes in exposure to medical marijuana advertising and subsequent adolescent marijuana use, cognitions, and consequences over seven years. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;188:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.031. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., Tucker J. S., Miles J. N., Ewing B. A., Shih R. A., Pedersen E. R. Alcohol and marijuana use trajectories in a diverse longitudinal sample of adolescents: Examining use patterns from age 11 to 17 years. Addiction. 2016;111:1825–1835. doi: 10.1111/add.13442. doi:10.1111/add.13442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. 2003. Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh27-1/18-29.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt E. M., Stucky B. D., Thissen D., Irwin D. E., Langer M., DeWalt D. A. Construction of the eight item PROMIS pediatric physical function scales: Built using item response theory. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar M. S., Davis J. P., Rodriguez A., Tucker J. S., Seelam R., D’Amico E. J. Disentangling within- and between-persons effects of shared risk factors on e-cigarette and cigarette use trajectories from late adolescence to young adulthood. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2019;21:1414–1422. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty179. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korupp S. E., Ganzeboom H. B. G., Van Der Lippe T. Do mothers matter? A comparison of models of the influence of mothers’ and fathers’ educational and occupational status on children’s educational attainment. Quality & Quantity. 2002;36:17–42. doi:10.1023/A:1014393223522. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ–15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:258–266. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008. doi:10.1097/00006842-20020300000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Strine T. W., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. W., Berry J. T., Mokdad A. H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;114:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod J., Oakes R., Copello A., Crome I., Egger M., Hickman M., Smith G. D. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: A systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. The Lancet. 2004;363:1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. doi:10.17226/24625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osilla K. C., Pedersen E. R., Ewing B. A., Miles J. N., Ramchand R., D’Amico E. J. The effects of purchasing alcohol and marijuana among adolescents at-risk for future substance use. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2014;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-38. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.-Y., Wu L.-T. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;177:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis T. S., Desai R. A., Cavallo D. A., Smith A. E., McFetridge A., Liss T. B., Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender differences in adolescent marijuana use and associated psychosocial characteristics. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2011;5:65–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d8dc62. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d8dc62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R. L., Kroenke K., Williams J. B. W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J. S., Rodriguez A., Pedersen E. R., Seelam R., Shih R. A., D’Amico E. J. Greater risk for frequent marijuana use and problems among young adult marijuana users with a medical marijuana card. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;194:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.028. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J., Jr., Kosinski M., Keller S. D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. doi:10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]