Abstract

Objective:

Sexual minority women report more problematic alcohol use and depression than heterosexual women. Despite evidence that sexual identity can change over time, most studies treat it as a static construct. As a result, little is known about the extent to which changes in sexual identity influence alcohol use and depression. The current study examined (a) changes in sexual identity over 36 months, (b) the associations between the number of changes in sexual identity and measures of alcohol use (typical weekly alcohol consumption, peak drinking, and alcohol-related consequences) and depression at the final assessment, and (c) baseline sexual identity as a moderator of the associations.

Method:

The analyses used four waves of data from a national U.S. sample of sexual minority women ages 18–25 (n = 1,057).

Results:

One third (34%) of participants reported at least one change in sexual identity over the course of the study. The number of changes in sexual identity was positively associated with typical weekly alcohol consumption and depression but was not significantly associated with peak drinking or alcohol-related consequences. None of the associations were moderated by baseline sexual identity.

Conclusions:

These findings provide additional evidence that sexual identity continues to change over time for a sizeable proportion of young adult sexual minority women and these changes are relevant to their health and well-being.

Previous research has demonstrated that lesbian and bisexual women (sexual minority women [SMW]) are more likely to report problematic alcohol use and depression than heterosexual women (e.g., Dermody et al., 2014; Drabble et al., 2013; Fish et al., 2018; Hughes et al., 2010; Talley et al., 2014). In the 2004–2005 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 20%–25% of SMW reported past-year heavy quantity drinking compared with 8% of heterosexual women (McCabe et al., 2009), and 44%–59% of SMW met criteria for a mood disorder in their lifetime compared with 31% of heterosexual women (Bostwick et al., 2010). Previous research has also demonstrated that sexual identity can change over time, especially among women (e.g., Diamond, 2005; Everett, 2015; Mock & Eibach, 2012; Ott et al., 2011; Savin-Williams et al., 2012). This fluctuation may be particularly common during emerging adulthood—a developmental period involving profound change including identity exploration, instability, and peak levels of substance use (Arnett, 2000, 2005; Parks & Hughes, 2007; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Despite robust evidence that SMW are at increased risk for problematic alcohol use and depression, most studies have treated sexual identity as a static construct, and it remains unclear if changes in sexual identity are associated with alcohol use and depression among SMW during emerging adulthood.

Changes in sexual identity

Traditional stage models of sexual minority identity development describe the process as linear, beginning with an awareness of same-gender attraction and ending with identification as non-heterosexual (Cass, 1979; Coleman, 1982; Troiden, 1988). However, scholars have criticized these models because they do not account for sexual fluidity across the life span (Diamond, 2008) or the experiences of bisexual individuals (Everett et al., 2016). In contrast to the assumed linear development of sexual identity, many young adults, especially women, report changes in sexual identity over time. For example, in a sample of young adults, 18% of women and 6% of men reported different sexual identities at baseline and 6 years later (Savin-Williams et al., 2012). Similarly, Everett (2015) found that 12% of young adults reported different sexual identities at baseline and 7 years later; of these, 70% became more same-sex oriented.

Although most participants in these studies initially identified as heterosexual, a few studies have examined changes in sexual identity in samples of sexual minorities. In a sample of 156 sexual minority youth (ages 14–21), 18% reported a different sexual identity than they reported at the baseline assessment a year earlier (Rosario et al., 2006). In addition, in a sample of 79 non-heterosexual women (ages 18–25), 32% reported both lesbian and non-lesbian identities at different points over 8 years (Diamond, 2005). Last, in a sample of 306 SMW (ages 18–82), 26% reported a change in their sexual identity in the 3–4 years between the baseline assessment and Wave 2, and 25% reported a change in their sexual identity in the 7 years between Waves 2 and 3 (Everett et al., 2016). These findings demonstrate that sexual identity can and often does change after initially adopting a non-heterosexual identity. However, some of these studies had small samples, included few bisexual individuals, or did not focus on the critical developmental period of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000, 2005; Parks & Hughes, 2007; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). To address these gaps, we assessed sexual identity four times over 36 months (baseline and 12, 24, and 36 months) in a large sample of young adult lesbian and bisexual women. By assessing sexual identity every year, we were able to capture changes over relatively short periods of time during an important developmental period.

Health implications of changes in sexual identity

Identity theories provide a foundation for understanding why changes in sexual identity may influence alcohol use and depression. For example, identity control theory (Burke, 2006) posits that changes in identity are often precipitated by cognitive dissonance and psychological distress experienced when a person’s internal experiences do not match external expectations (e.g., if their sexual attractions are not consistent with expectations for their sexual identity). This can lead individuals to redefine their identity in an effort to reduce dissonance and distress, which may have benefits in the long term but can also lead to cognitive and emotional disruptions as one navigates intrapersonal and interpersonal changes. When these changes overwhelm coping abilities, well-being is likely to suffer and individuals may resort to maladaptive coping strategies, such as alcohol misuse. Further, some people experience “awareness that facets of their own sexual orientation are perceived as inconsistent, unreliable, or uncertain” (referred to as sexual orientation self-concept ambiguity; Talley & Stevens, 2017, p. 634), which has also been linked to alcohol misuse and depression (Talley & Stevens, 2017). As people experience changes in their relationships and attractions, they may be confronted with perceptions of their sexual orientation as inconsistent, which may result in negative outcomes (Talley et al., 2016). Ueno (2010) also suggested that having one’s first same-sex experience in young adulthood may be associated with negative mental health outcomes because it may disrupt routines and social networks, increase the demand for adaptations to the new social environment, threaten one’s self-identity, and signify entry into a stigmatized status.

Although scholars have noted the potential for changes in sexual identity to influence alcohol use and depression, only a few studies have tested this hypothesis. In a study that examined trajectories of sexual orientation during college, Talley et al. (2012) identified a group of women who largely identified as exclusively heterosexual but experienced increases in same-sex attractions/behaviors or shifts away from exclusively heterosexual over time. Compared with exclusively heterosexual women, this group reported a higher number of negative alcohol-related consequences and higher levels of using alcohol to cope with negative affect. Fish and Pasley (2015) also examined trajectories of sexual orientation and identified two groups that changed over time: one that mainly reported different-sex attractions/behaviors at three out of four waves but reported an increase in same-sex attraction and identification as “mostly heterosexual” or bisexual during one wave, and one that consistently reported different-sex attractions/behaviors during the first three waves but then reported an increase in same-sex attraction and non-heterosexual identification at the fourth wave. Across waves, each of these groups tended to report greater alcohol use and depression than the exclusively heterosexual group. In addition, using data from Waves 3 and 4 of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, Everett (2015) found that changes toward more same-sex–oriented identities over a 7-year period were associated with increases in depression. Although none of these studies focused exclusively on sexual minorities, Ott et al. (2013) found that sexual minority youth who later identified as completely heterosexual and those who reported multiple changes in their sexual identity reported more binge drinking during young adulthood than those who did not report any changes in their sexual identity. In addition, in a sample of SMW, Everett et al. (2016) found that changes toward more same-sex–oriented identities were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Further, the associations between changes in sexual identity (including changes toward more and less same-sex–oriented identities) and depressive symptoms were stronger for SMW who had identified with their baseline sexual identity longer.

These findings highlight the importance of research that evaluates the impact of changes in sexual identity on alcohol use and depression. Given that only two of the above studies focused specifically on sexual minorities (and only one on SMW), additional research is needed to better understand the extent to which findings generalize to women who already identify as sexual minorities and whether changes in sexual identity have different consequences for women who initially identify as lesbian compared with those who initially identify as bisexual. Bisexual women are at greater risk for problematic alcohol use and depression compared with both heterosexual and lesbian women (Hughes et al., 2010; McCabe et al., 2009; Ross et al., 2018; Wilsnack et al., 2008), and they experience discrimination from both heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals (Brewster & Moradi, 2010; Feinstein & Dyar, 2017). Given the stigmatization of bisexuality, the associations between changes in sexual identity and health outcomes may be weaker for women who initially identify as bisexual than for those who initially identify as lesbian because their changes in sexual identity would reflect changes toward less stigmatized identities. In sum, it is important to examine the associations between changes in sexual identity and health outcomes among young adult SMW. Such information can be used to identify the periods of highest risk and to inform the development of interventions to address the needs of this high-risk population.

Current study

The goals of the current study were to examine (a) changes in sexual identity over 36 months in a large national U.S. sample of 18- to 25-year-old SMW, (b) the associations between the number of changes in sexual identity and measures of alcohol use (typical weekly alcohol consumption, peak drinking, and alcohol-related consequences) and depression, and (c) baseline sexual identity as a moderator of the associations. We hypothesized that a sizeable proportion of SMW would report changes in sexual identity over 36 months, that the number of changes in sexual identity would be positively associated with alcohol use and depression, and that the associations would be weaker for those who initially identified as bisexual than for those who initially identified as lesbian.

Method

Participants were recruited through advertisements on Facebook and Craigslist. Eligibility criteria included women who (a) lived in the United States, (b) had a valid email address, (c) were between ages 18 and 25, and (d) identified as lesbian or bisexual. A total of 4,119 women completed the screening, and 1,877 were eligible for the longitudinal study. Participants received $25 for completing the baseline survey and were invited to complete annual follow-up surveys at 12, 24, and 36 months. For each follow-up survey, participants received $30. Of the 1,877 eligible participants, 1,057 completed the baseline survey. The average age of the women in the analytic sample was 21.4 (SD = 2.1); 21.6% reported a non-White race and 11.3% reported Hispanic ethnicity. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved all of the procedures and informed consent was given for participation in the study.

Measures

Demographics.

At baseline, participants were asked to report their age, race, ethnicity, educational status, and relationship status. At each wave, participants were also asked to report their sexual identity. Based on their reporting of sexual identity across waves, we counted the number of times a participant indicated a change in their sexual identity over the course of the study (range: 0–3). Because the number of women who reported three changes was small (2.0%), we created a category indicating two or more changes for use in analyses (i.e., participants were coded as reporting 0, 1, or 2+ changes).

Typical weekly alcohol consumption.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985) was used to assess typical weekly alcohol consumption. Participants were instructed to consider a typical week during the last 12 months. They were then asked, “How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), do you drink on each day of a typical week?” Participants indicated the average number of drinks they consumed on each day of the week. Responses were summed across days to compute a total typical weekly alcohol consumption score (at the 36-month assessment, M = 6.4, SD = 8.3).

Peak drinking.

One question from the Quantity Frequency Peak Index (Baer, 1993; Marlatt et al., 1995) was used to assess peak drinking. Participants were asked: “Think of the occasion you drank the most this past month. How much did you drink?” Response options ranged from 0 to 25+ drinks (at the 36-month assessment, M = 4.6, SD = 4.1).

Alcohol-related consequences.

The Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read et al., 2006) was used to assess alcohol-related consequences. The YAACQ includes 48 items, each of which describes a potential consequence of alcohol use. Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced each consequence in the past 30 days (1 = yes, 0 = no). Responses were summed across items to compute a total score (at the 36-month assessment, M = 5.6, SD = 7.7). The YAACQ has demonstrated reliability and validity in samples of young adults (Read et al., 2006), and Cronbach’s α was .95 at baseline and 36 months in the current sample.

Depression symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess depression symptoms. Participants were asked to rate 20 items (e.g., “I felt depressed” and “I felt lonely”) on a 4-point scale (0 = rarely or none of the time, 3 = most or all of the time). Responses were summed across items to compute a total score (at the 36-month assessment, M = 20.7, SD = 12.5). The CES-D has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in samples of sexual minorities (Cooperman et al., 2003; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2011), and Cronbach’s α was .92 in the current sample.

Data analysis

Negative binomial and linear regression models were used to examine the associations between the number of changes in sexual identity over 36 months and the outcomes at the 36-month assessment. The number of changes in sexual identity was entered as an ordinal variable. Sensitivity analyses using dummy-coded variables instead of an ordinal variable showed results that were consistent with the ordinal findings. Because the alcohol variables were non-negative integers with positive skew, they were treated as counts in statistical models by specifying a negative binomial distribution. Negative binomial was selected over Poisson because of evidence of over-dispersion. Model coefficients were exponentiated to yield count ratios (CRs; also known as rate ratios) that describe the proportional change in the outcome associated with the number of changes in sexual identity. Depression showed a relatively normal distribution and was treated as continuous in ordinary least squares linear models. Separate models were run for each outcome. Additional covariates included baseline sexual identity (0 = lesbian, 1 = bisexual), age, race (0 = White, 1 = non-White), ethnicity (0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), baseline college status (0 = not currently a 2- or 4-year college student, 1 = currently a 2- or 4-year college student), baseline relationship status (0 = not in a dating or committed relationship, 1 = in a dating or committed relationship), and the baseline level of the outcome. Other sensitivity analyses included relationship status as the number of times participants reported being in a relationship over the course of the study. This did not alter results for the “number of changes in sexual identity” variable and thus we report findings based on the adjustment for baseline relationship status. Last, we also examined whether associations between the number of changes in sexual identity and the outcomes were moderated by baseline sexual identity by including an interaction term.

There were missing data over time for sexual identity and the 36-month outcome variables. Sexual identity data were available at the 12- and 24-month follow-up waves for 77.3% and 68.8% of the original sample, respectively. At the 36-month wave, 68.2% had non-missing outcome and sexual identity data. To account for missingness, we used multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE; Azur et al., 2011). Analyses using multiply imputed data should yield unbiased estimates under the assumption of missing at random; that is, missingness is not attributable to unmeasured variables (Graham, 2009). Using MICE, variables were imputed according to their distribution (continuous, binary, or count). In the models to create the imputed data, when possible we used all available variables that were included in the statistical models and those versions of the variables at the 12- and 24-month waves (e.g., baseline, 12-, 24-, and 36-month typical weekly alcohol use). However, because of low prevalence of those reporting heterosexual identity at follow-up visits, we could not obtain reliably stable imputed variables for sexual identity at all waves. Instead, only baseline sexual orientation was included and a variable for the number of changes in sexual identity across the study was created. Further, we included auxiliary variables such as measures of perceived discrimination and internalized homonegativity. Twenty imputed data sets were created and regression models were run across these data sets. The results were combined and standard errors were estimated using Rubin’s rules, which account for between-and within-imputation variation (Rubin, 2004). All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

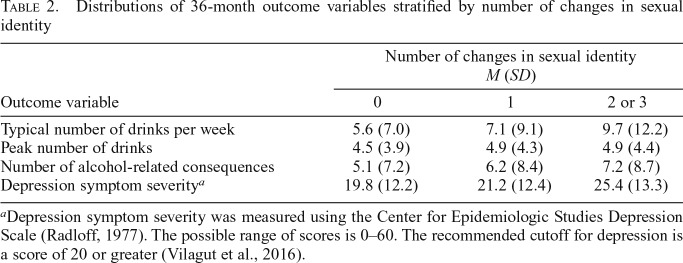

Baseline characteristics of the full sample (n = 1,057) are presented in Table 1. A total of 34.4% of participants reported at least one change in sexual identity during the study period, with 24.6% reporting one change and 9.8% reporting two or more changes. The proportion of women who reported one change was similar for those who initially identified as bisexual (25.0%) and lesbian (24.1%). However, women who initially identified as bisexual were more likely to report two or more changes (11.7%) than those who initially identified as lesbian (7.0%), and this difference was significant (b = 0.61, p = .026).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the full sample (n = 1,057)

| Characteristic | M (SD) or % |

| Bisexual identity (vs. lesbian identity) | 59.5% |

| Age, in years | 21.4 (2.1) |

| Non-White race | 21.6% |

| Latinx ethnicity | 11.3% |

| 2- or 4-year college student | 54.8% |

| In a dating or committed relationship | 65.2% |

| Typical number of drinks per week | 8.3 (11.5) |

| Peak number of drinks | 5.1 (4.6) |

| Number of alcohol-related consequences | 8.0 (9.2) |

| Depression symptom severitya | 23.4 (12.4) |

Depression symptom severity was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). The possible range of scores is 0–60. The recommended cutoff for depression is a score of 20 or greater (Vilagut et al., 2016).

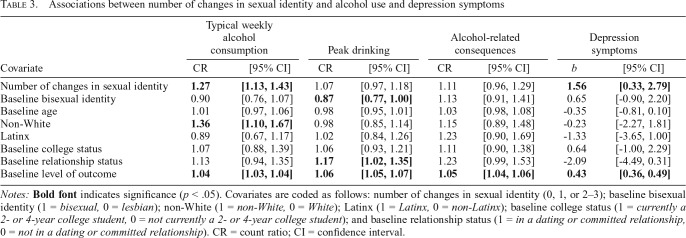

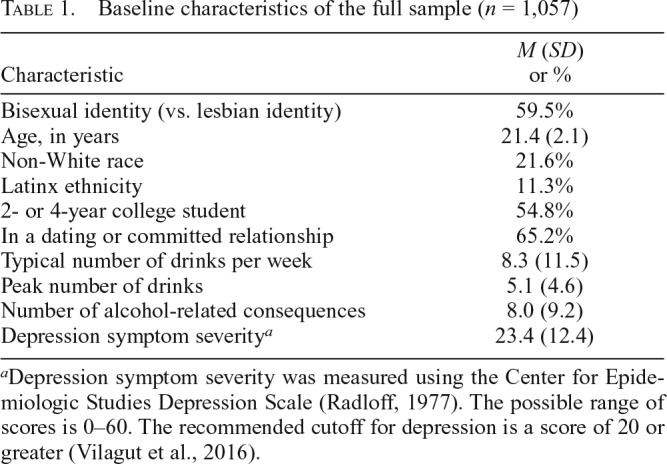

Distributions of the outcome variables at the 36-month assessment stratified by the number of changes in sexual identity are presented in Table 2. Associations between the number of changes in sexual identity and the outcome variables are presented in Table 3. Women who reported a greater number of changes in sexual identity reported greater typical weekly alcohol use at the 36-month assessment after adjusting for covariates including baseline sexual identity and baseline typical weekly alcohol use (CR = 1.27, 95% CI [1.13, 1.43]). Similarly, women who reported a greater number of changes in sexual identity also reported greater depression at the 36-month assessment after adjusting for covariates (b = 1.56, 95% CI [0.33, 2.79]). In contrast, the number of changes in sexual identity was not significantly associated with peak drinking or alcohol-related consequences, although the direction of the associations was also positive. None of the tests of interactions between baseline sexual identity and the number of changes in sexual identity were significant (ps ranged from .24 to .67).

Table 2.

Distributions of 36-month outcome variables stratified by number of changes in sexual identity

| Number of changes in sexual identity M (SD) |

|||

| Outcome variable | 0 | 1 | 2 or 3 |

| Typical number of drinks per week | 5.6 (7.0) | 7.1 (9.1) | 9.7 (12.2) |

| Peak number of drinks | 4.5 (3.9) | 4.9 (4.3) | 4.9 (4.4) |

| Number of alcohol-related consequences | 5.1 (7.2) | 6.2 (8.4) | 7.2 (8.7) |

| Depression symptom severitya | 19.8 (12.2) | 21.2 (12.4) | 25.4 (13.3) |

Depression symptom severity was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). The possible range of scores is 0–60. The recommended cutoff for depression is a score of 20 or greater (Vilagut et al., 2016).

Table 3.

Associations between number of changes in sexual identity and alcohol use and depression symptoms

| Typical weekly alcohol consumption |

Peak drinking |

Alcohol-related consequences |

Depression symptoms |

|||||

| Covariate | CR | [95% CI] | CR | [95% CI] | CR | [95% CI] | b | [95% CI] |

| Number of changes in sexual identity | 1.27 | [1.13, 1.43] | 1.07 | [0.97, 1.18] | 1.11 | [0.96, 1.29] | 1.56 | [0.33, 2.79] |

| Baseline bisexual identity | 0.90 | [0.76, 1.07] | 0.87 | [0.77, 1.00] | 1.13 | [0.91, 1.41] | 0.65 | [-0.90, 2.20] |

| Baseline age | 1.01 | [0.97, 1.06] | 0.98 | [0.95, 1.01] | 1.03 | [0.98, 1.08] | -0.35 | [-0.81, 0.10] |

| Non-White | 1.36 | [1.10, 1.67] | 0.98 | [0.85, 1.14] | 1.15 | [0.89, 1.48] | -0.23 | [-2.27, 1.81] |

| Latinx | 0.89 | [0.67, 1.17] | 1.02 | [0.84, 1.26] | 1.23 | [0.90, 1.69] | -1.33 | [-3.65, 1.00] |

| Baseline college status | 1.07 | [0.88, 1.39] | 1.06 | [0.93, 1.21] | 1.11 | [0.90, 1.38] | 0.64 | [-1.00, 2.29] |

| Baseline relationship status | 1.13 | [0.94, 1.35] | 1.17 | [1.02, 1.35] | 1.23 | [0.99, 1.53] | -2.09 | [-4.49, 0.31] |

| Baseline level of outcome | 1.04 | [1.03, 1.04] | 1.06 | [1.05, 1.07] | 1.05 | [1.04, 1.06] | 0.43 | [0.36, 0.49] |

Notes: Bold font indicates significance (p < .05). Covariates are coded as follows: number of changes in sexual identity (0, 1, or 2–3); baseline bisexual identity (1 = bisexual, 0 = lesbian); non-White (1 = non-White, 0 = White); Latinx (1 = Latinx, 0 = non-Latinx); baseline college status (1 = currently a 2- or 4-year college student, 0 = not currently a 2- or 4-year college student); and baseline relationship status (1 = in a dating or committed relationship, 0 = not in a dating or committed relationship). CR = count ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

A substantial proportion of the sample (34.4%) reported at least one change in sexual identity over 36 months. These findings are consistent with accumulating evidence that changes in sexual identity are relatively common among young women (Diamond, 2000, 2005; Dickson et al., 2013; Everett, 2015; Everett et al., 2016; Mock & Eibach, 2012; Ott et al., 2011; Savin-Williams et al., 2012). Further, they contradict traditional stage models of sexual minority identity development, which describe it as a linear process that ends with a nonheterosexual identity (Cass, 1979; Coleman, 1982; Troiden, 1988). Instead, many SMW report changes in sexual identity after the initial adoption of a nonheterosexual identity, indicating that sexual identity development continues during emerging adulthood. Of note, women who initially identified as bisexual were more likely to report two or more changes in sexual identity compared with those who initially identified as lesbian. However, they did not differ in their likelihood of reporting one change in sexual identity, and we did not assess their motivations for changing (e.g., fluctuations in attractions, societal pressure), an important area for future studies. We encourage researchers to conceptualize sexual identity as a characteristic that can change and to assess it at every time point in longitudinal studies to accurately represent sexual identity at a given time to advance our understanding of changes in sexual identity and their implications for health.

Previous research has generally found that changes in sexual orientation are associated with greater alcohol use or depression (Everett, 2015; Fish & Pasley, 2015; Ott et al., 2013; Talley et al., 2012), but few studies have focused specifically on sexual minorities. This is important because moving into a marginalized group (e.g., from a heterosexual identity to a sexual minority identity) may have a greater impact on health than moving into a less marginalized group (e.g., from a sexual minority to a heterosexual identity, from a bisexual identity to a lesbian identity). In our sample, women who reported more changes in sexual identity reported greater typical weekly alcohol consumption and depression. The model-predicted means (i.e., adjusted for covariates) for typical weekly alcohol consumption at 36 months increased as the number of changes in sexual identity increased (5.17 for 0 changes, 6.61 for 1 change, and 8.47 for 2+ changes). According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (2015), eight or more drinks per week is considered highrisk drinking for women. As such, the women in our sample who reported two or more changes in sexual identity tended to exceed the cutoff for high-risk drinking. The model-predicted means (i.e., adjusted for covariates) for depression at 36 months also increased as the number of changes in sexual identity increased (20.02 for 0 changes, 21.58 for 1 change, and 23.14 for 2+ changes). Based on a recommended cutoff score of 20 or greater on the CES-D (Vilagut et al., 2016), women in our sample who did not report any changes in sexual identity tended to be at the cutoff, whereas women in our sample who reported changes tended to be beyond the cutoff. It is difficult to directly compare these findings with findings from previous studies given differences in methodologies and analytic approaches. However, these findings are consistent with the notion that changes in identity can lead to cognitive and emotional disruptions as one navigates the intrapersonal and interpersonal changes (Burke, 2006). As suggested earlier, when changes overwhelm coping abilities, well-being is likely to suffer and individuals may resort to maladaptive coping strategies, such as alcohol misuse. Loss of social connections through changes in identity may also increase social isolation and risk for depression. Moreover, we know that life events, even positive ones, can be stressful and increase risk for depression. However, change in sexual identity has not typically been considered in inventories of stressful life events. Based on our findings, it may be important for future studies to do so.

In contrast, the number of changes in sexual identity was not significantly associated with peak drinking or alcohol-related consequences. As such, SMW who change their sexual identity may drink more than those who do not, but their level of drinking does not appear to lead to alcohol-related consequences, at least not in the short term. It is important to note that our follow-up over 36 months cannot capture the potentially longer term consequences of more frequent drinking. Although several studies have found that the consequences of changes in sexual identity depend on the direction of the change, most participants in previous studies initially identified as heterosexual and, as noted, moving into a marginalized group may have a greater impact on health than moving into a less marginalized group. In our sample, associations between the number of changes in sexual identity and outcomes did not differ between women who identified as lesbian versus bisexual at baseline. These findings suggest that the consequences of changing one’s sexual identity may be similar for women who initially identify as lesbian and those who initially identify as bisexual, but we were unable to examine whether specific changes were associated with differential risk due to missing data.

The current findings have important implications for efforts to reduce alcohol misuse and depression among SMW. First, women who are in the process of changing their sexual identity (e.g., those who are questioning their identity, those who are beginning to claim a new identity) may benefit from support during this transitional period. Clinicians may be able to help these women by exploring how changes in sexual identity might affect other aspects of their life (e.g., relationships, community involvement, exposure to stigma) and by identifying healthy strategies for coping with this transition. The current findings may also help to normalize sexual identity change, which may ultimately reduce distress among those in the process of such transitions. Existing models of sexual identity development tend to assume that sexual identity is immutable after adopting one’s “true” identity. These models may send the message that changing one’s sexual identity reflects pathology rather than being a common developmental process, which may lead SMW who change their sexual identity to believe that something is wrong with them. Clinicians can play a role in combating this stigmatizing and damaging message by affirming changes in sexual identity as a normal part of development for many people.

The current findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, despite the benefits of using the Internet to recruit a national sample, it remains unclear if findings generalize to the broader population of SMW. Second, we used multiple imputation to account for missing data over time. As noted, because of the low prevalence of those reporting heterosexual identity at follow-up visits, we could not obtain reliably stable imputed variables for sexual identity at all waves. As a result, we created a variable for the number of changes in sexual identity over the course of the study. It will be important for future research to examine the consequences of changes in sexual identity among SMW, including changes in specific directions. Further, participants were asked to choose from four response options for sexual identity (lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual, and prefer not to answer), and it will be important for future studies to examine a broader range of identities (e.g., queer, pansexual). Third, we were unable to examine the associations between change in sexual identity during a given year and outcomes during the subsequent year, which is necessary to understand the temporality of these associations. Last, we did not assess participants’ motivations for changing their sexual identities, and it is possible that the consequences of changing one’s sexual identity depend on one’s motivation.

Despite limitations, the current findings add to the literature on sexual identity development, demonstrating that it continues throughout young adulthood for many SMW. Further, changes in sexual identity are associated with increases in typical alcohol consumption and depression, but not drinking-related consequences. Given that developmental processes, such as changes in sexual identity, are embedded in the broader sociocultural context, it will be important for future studies to examine whether these processes vary based on other individual characteristics (e.g., age, race, ethnicity). In sum, continued research on change in sexual identity has the potential to improve our understanding of sexual orientation–related health disparities and to inform interventions to reduce these problems among those at greatest risk.

Footnotes

Data collection was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA018292; principal investigator: Debra Kaysen). Article preparation was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K08DA045575; principal investigator: Brian A. Feinstein) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA013328-13; principal investigator: Tonda L. Hughes).The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Arnett J. J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–254. doi:10.1177/002204260503500202. [Google Scholar]

- Azur M. J., Stuart E. A., Frangakis C., Leaf P. J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2011;20:40–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329. doi:10.1002/mpr.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer J. S. Etiology and secondary prevention of alcohol problems with young adults. In: Baer J. S., Marlatt G. A., McMahon R. J., editors. Addictive behaviors across the lifespan. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 111–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick W. B., Boyd C. J., Hughes T. L., McCabe S. E. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster M. E., Moradi B. Perceived experiences of antibisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:451–468. doi: 10.1037/cou0000156. doi:10.1037/a0021116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke P. J. Identity change. School Psychology Quarterly. 2006;69:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cass V. C. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. doi:10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E. Developmental stages of the coming out process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1982;7:31–43. doi: 10.1300/j082v07n02_06. doi:10.1300/J082v07n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Parks G. A., Marlatt G. A. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman N. A., Simoni J. M., Lockhart D. W. Abuse, social support, and depression among HIV-positive heterosexual, bisexual and lesbian women. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7:49–66. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_04. doi:10.1300/J155v07n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody S. S., Marshal M. P., Cheong J., Burton C., Hughes T., Aranda F., Friedman M. S. Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:30–39. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. M. Sexual identity, attractions, and behavior among young sexual-minority women over a 2-year period. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:241–250. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.2.241. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. M. A new view of lesbian subtypes: Stable versus fluid identity trajectories over an 8-year period. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:119–128. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00174.x. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L. M. Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson N., van Roode T., Cameron C., Paul C. Stability and change in same-sex attraction, experience, and identity by sex and age in a New Zealand birth cohort. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:753–763. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0063-z. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-0063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L., Trocki K. F., Hughes T. L., Korcha R. A., Lown A. E. Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:639–648. doi: 10.1037/a0031486. doi:10.1037/a0031486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett B. Sexual orientation identity change and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2015;56:37–58. doi: 10.1177/0022146514568349. doi:10.1177/0022146514568349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett B. G., Talley A. E., Hughes T. L., Wilsnack S. C., Johnson T. P. Sexual identity mobility and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis of moderating factors among sexual minority women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016;45:1731–1744. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0755-x. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0755-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein B. A., Dyar C. Bisexuality, minority stress, and health. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2017;9:42–49. doi: 10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3. doi:10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. N., Hughes T. L., Russell S. T. High-intensity binge drinking and sexual identity: Findings from a US national sample. Addiction. 2018;113:749–758. doi: 10.1111/add.14041. doi:10.1111/add.14041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. N., Pasley K. Sexual (minority) trajectories, mental health, and alcohol use: A longitudinal study of youth as they transition to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44:1508–1527. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0280-6. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. W. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman L. B., Phillips G., II, Jones K. C., Outlaw A. Y., Fields S. D., Smith J. C. & the YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group. Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25(Supplement 1):S39–S45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877. doi:10.1089/apc.2011.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T. L., Szalacha L. A., Johnson T. P., Kinnison K. E., Wilsnack S. C., Cho Y. Sexual victimization and hazardous drinking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1152–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G. A., Baer J. S., Larimer M. Preventing alcohol abuse in college students: A harm-reduction approach. In: Boyd G. M., Howard J., Zucker R. A., editors. Alcohol problems among adolescents: Current directions in prevention research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., Hughes T. L., Bostwick W. B., West B. T., Boyd C. J. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock S. E., Eibach R. P. Stability and change in sexual orientation identity over a 10-year period in adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9761-1. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9761-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M. Q., Corliss H. L., Wypij D., Rosario M., Austin S. B. Stability and change in self-reported sexual orientation identity in young people: Application of mobility metrics. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:519–532. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9691-3. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9691-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M. Q., Wypij D., Corliss H. L., Rosario M., Reisner S. L., Gordon A. R., Austin S. B. Repeated changes in reported sexual orientation identity linked to substance use behaviors in youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks C. A., Hughes T. L. Age differences in lesbian identity development and drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:361–380. doi: 10.1080/10826080601142097. doi:10.1080/10826080601142097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Read J. P., Kahler C. W., Strong D. R., Colder C. R. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies of Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M., Schrimshaw E. W., Hunter J., Braun L. Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. doi:10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. E., Salway T., Tarasoff L. A., MacKay J. M., Hawkins B. W., Fehr C. P. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research. 2018;55:435–456. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D. B. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams R. C., Joyner K., Rieger G. Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9913-y. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9913-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Maggs J. L. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley A. E., Brown S. L., Cukrowicz K., Bagge C. L. Sexual self-concept ambiguity and the interpersonal theory of suicide risk. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2016;46:127–140. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12176. doi:10.1111/sltb.12176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley A. E., Hughes T. L., Aranda F., Birkett M., Marshal M. P. Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: Intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:295–303. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301627. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley A. E., Sher K. J., Steinley D., Wood P. K., Littlefield A. K. Patterns of alcohol use and consequences among empirically derived sexual minority subgroups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:290–302. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.290. doi:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley A. E., Stevens J. E. Sexual orientation self-concept ambiguity: Scale adaptation and validation. Assessment. 2017;24:632–645. doi: 10.1177/1073191115617016. doi:10.1177/1073191115617016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiden R. R. Homosexual identity development. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 1988;9:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(88)90056-3. doi:10.1016/0197-0070(88)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K. Same-sex experience and mental health during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. The Sociological Quarterly. 2010;51:484–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01179.x. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. 2015. p. 101. Retrieved from http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- Vilagut G., Forero C. G., Barbaglia G., Alonso J. Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack S. C., Hughes T. L., Johnson T. P., Bostwick W. B., Szalacha L. A., Benson P., Kinnison K. E. Drinking and drinking-related problems among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:129–139. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.129. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]