Abstract

There is a need for luminescent probes, which display both long excitation and emission wavelengths and long decay times. We synthesized and characterized an osmium metal–ligand complex which displays a mean decay time of over 100 ns when bound to proteins. [Os(1,10-phenanthroline)2(5-amino-1,10-phenanthroline)](PF6)2 can be excited at wavelengths up to 650 nm, and displays an emission maximum near 700 nm. The probe displays a modest but useful maximum fundamental anisotropy near 0.1 for 488-nm excitation, and thus convenient when using an argon ion laser. [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 is readily activated to the isothiocyanate for coupling to proteins. When covalently linked to bovine serum albumin the intensity decay is moderately heterogeneous with a mean decay time of 145 ns. The anisotropy decay of the labeled protein displays a correlation time near 40 ns. This relatively long lifetime luminophores can be useful as a biophysical probe or in clinical applications such as fluorescence polarization immunoassays.

1. Introduction

During the past 10 years there has been an extensive effort to develop fluorescent probes for use with red and near infrared (NIR) wavelengths [1–3]. Most such fluorophores have been based on the cyanine, squaraine, oxazine and similar structures [4–7]. These probes display the favorable characteristics of high extinction coefficients and moderately high quantum yields. However, the currently available red-NIR probes do suffer disadvantages. They typically display small Stokes’ shifts, which makes it difficult to reject scattered light. Additionally, the high extinction coefficient of these dyes results in a high probability of emission [8] and thus short decay times. The decay times of red-NIR probes are typically < 1 ns. In fact, if one examines all available fluorescence probes, most decay times are below 10 ns. Since the autofluorescence from biological samples is also on the nanosecond timescale, the autofluorescence cannot be rejected with time-gating methods.

In order to circumvent the usual nanosecond limits of fluorescence there have been efforts to use alternative luminescent substances. The emission from lanthanides has been used because of the millisecond decay times [9–11]. Also, the lanthanides are not quenched by dissolved oxygen. These long lifetimes have resulted in the use of lanthanides with gated detection for high sensitivity immunoassays [12–17]. However, the lanthanides do not display useful polarization and thus have not been used as hydrodynamic probes. Phosphorescence has also been used for microsecond to millisecond timescale measurements [18]. However, the use of phosphorescence is limited by the small number of substances, which display useful phosphorescence, and the large extent of quenching by dissolved oxygen.

The luminescent metal–ligand complex provide a general approach to develop microsecond probes with moderately long wavelengths. Transition metals such as ruthenium, rhenium, and osmium, when bound to diimine ligands, display a wide range of spectral properties [19–22]. The emission spectra range from the near ultraviolet to the NIR, and the decay times range from 10 ns to over 10 μs. Importantly, some MLCs display high fundamental anisotropies [23,24], making them useful for measurement of rotational diffusion on the microsecond timescale and in clinical assays.

An unfortunate property of the metal–ligand complex is that the quantum yields and decay times decrease at longer absorption and emission wavelength. This effect is due to the energy gap law, which states that the rate of non-radiative decay increases as the excited state energy becomes closer to the ground state [21,25]. As a result complexes such as [Os(2,2-bipyridine)3]2+ display low quantum yields and decay times near 15 ns in water [26].

In an effort to obtain a long wavelength MLC with a larger quantum yield and lifetimes we synthesized the phenanthroline complex of osmium (Os) shown in Scheme 1. The use of phenanthroline ligands, rather than bipyridyl ligands, resulted in an approximate 10-fold longer lifetime than for the bipyridyl complex, consistent with the higher quantum yield observed for [Os(phen)3](PF6)2 vs. [Os(bpy)3](PF6)2[27]. The amino group was activated for conjugation to proteins. This osmium MLC displays modest and useful anisotropy, and its decay time is adequately long to allow gated detection.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of [Os(phen)2(aphen)]2+.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental

Ammonium hexachloroosmate (IV), 1,10-phenanthroline (phen), 5-amino-1,10-phenanthroline (aphen), all solvents and phosphate salts for buffer were purchased from Aldrich and used with out further purification. The starting material, cis-Os(phen)2-Cl2, for making [Os(phen)2-(aphen)](PF6)2 was prepared by using reported methods [28,29].

2.2. Synthesis of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2

cis-Os(phen)2Cl2 and 5-amino-1,10-phenanthroline in 1:1.2 molar ratios, respectively, were heated to reflux under nitrogen for 8 h in DMF (dimethyl foramide). On completion of the reaction DMF was removed by vacuum and the brown powder was dissolved in water and filtered. The compound was isolated from water by adding a saturated water solution of ammonium hexafluorophosphate, which gave a dark brown precipitate, then were filtered and dried. The compound was further purified by column chromatography by passing over alumina with solvent (acetonitrile/toluene) mixture.

To activate the amino group of [Os(phen)2-(phenNH2)](PF6)2, the compound was dissolved in dry CH2Cl2. Thiophosgene (thiocarbonyl chloride — CSCl2) was added in approximately five-fold molar excess to the solution and the mixture was stirred for 1 h in a fume hood. Then the same amount of thiophosgene was added and the reaction was left to proceed for 1 more hour. The progress and completion of the reaction was checked by thin layer chromatography using Silica Gel 60 F254 plates with acetonitrile as the solvent. After the completion of the reaction the solvent was evaporated by a gentle flow of nitrogen.

2.3. Protein labeling

Bovine serum albumin (Sigma) was dissolved in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 9.0) and activated MLC was added to the solution. The coupling reaction was left to proceed for 30 min and the labeled BSA was separated from the free probe by passing the mixture through a Sephadex G15 column equilibrated with the Tris buffer (pH = 9.0).

2.4. Spectroscopic measurements

Absorption spectra were recorded using a Hewlett Packard 8543 spectro-photometer. Emission spectra were recorded using a AB2 spectrofluorometer from Spectronics, Inc. Excitation and emission anisotropy spectra were measured on a SLM 8000 spectrofluorometer, in glycerol at −65°C. Unless otherwise indicated, all measurements were performed at 23°C.

Luminescence intensity and anisotropy decay were performed using frequency-domain instrumentation described previously [30,31]. Excitation was accomplished with an air-cooled argon ion laser operating at 488 nm. The laser output was amplitude modulated using an electro-optic modulator. For measurements of the intensity decay of osmium complex in water we used a frequency-doubled Ti:Sapphire laser, 445 nm, with a pulse picker to reduce the repetition rate to 80 kHz. Magic angle polarizer conditions were used to measure the intensity decays. The emission was isolated using a 700-nm interference filter, 75-nm bandpass, from Intor, Inc., Socorro, NM. For some measurements we also used a Corning 3–70 filter which transmits above 500 nm.

The FD intensity decay data were fit to the multi-exponential model

| (1) |

where αi are the pre-exponential factors and τi are the decay times. The fractional contribution of each component to the steady state intensity are given by

| (2) |

The mean decay time is given by

| (3) |

The parameter values αi and τi were recovered by non-linear least squares analysis [32,33]. The uncertainties in the phase and modulation values were taken as δp = 0.3° and δm = 0.008, respectively. The range of αi and τi values consistent with the data were determined with consideration of correlation between the parameters [34].

Anisotropy decays were obtained by least squares analysis of the differential polarized phase and modulation ratio data [31,35]. These data were fitted to

| (4) |

where r0k are the amplitudes and θk the rotational correlation times. The uncertainties in the differential phase and modulation ratios were assumed to be δΔ = 0.3°C and δΛ = 0.008, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Spectral properties of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2

Absorption and emission spectra of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 are shown in Fig. 1. The absorption extends to over 600 nm, allowing this complex to be excited with laser diodes at 635 nm or red light-emitting diodes. The emission displays a large Stokes’ shift with a maximum near 700 nm. We estimated the luminescence quantum yield of [Os(phen)2(aphen)]2+ by comparison with [Os(bpy)3]3+ which is reported to have a quantum yield of 0.00074 in water at room temperature [26]. The intensity of [Os(phen)2(aphen)]2+ is 3.9-fold higher, suggesting a quantum yield of 0.0029. In deoxygenated acetonitrile at room temperature the intensity of [Os(phen)2(aphen)]2+ is approximately 1.83-fold higher than that of [Os(bpy)3]2+, suggesting a quantum yield of 0.085 [27].

Fig. 1.

Spectral characteristics of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 complex in glycerol. The absorption spectra (dotted line) and emission spectra (dashed line) were collected at 23°C. The excitation anisotropy (solid line, λem = 680 nm), and emission anisotropy (opened circles, λexc = 580 nm) spectra were measured at −65°C.

For measurements of rotational diffusion it is important that the probe displays a non-zero anisotropy. Excitation and emission anisotropy spectra of [Os(phen)2(aphen)]2+ in glycerol at −65°C are shown in Fig. 1. A maximum anisotropy near 0.1 was found for excitation near 488 nm. While this anisotropy is less than that found for other metal–ligand complexes [23,24,26,27], this value is adequate for measurement of steady-state or anisotropy decay, but with somewhat decreased resolution.

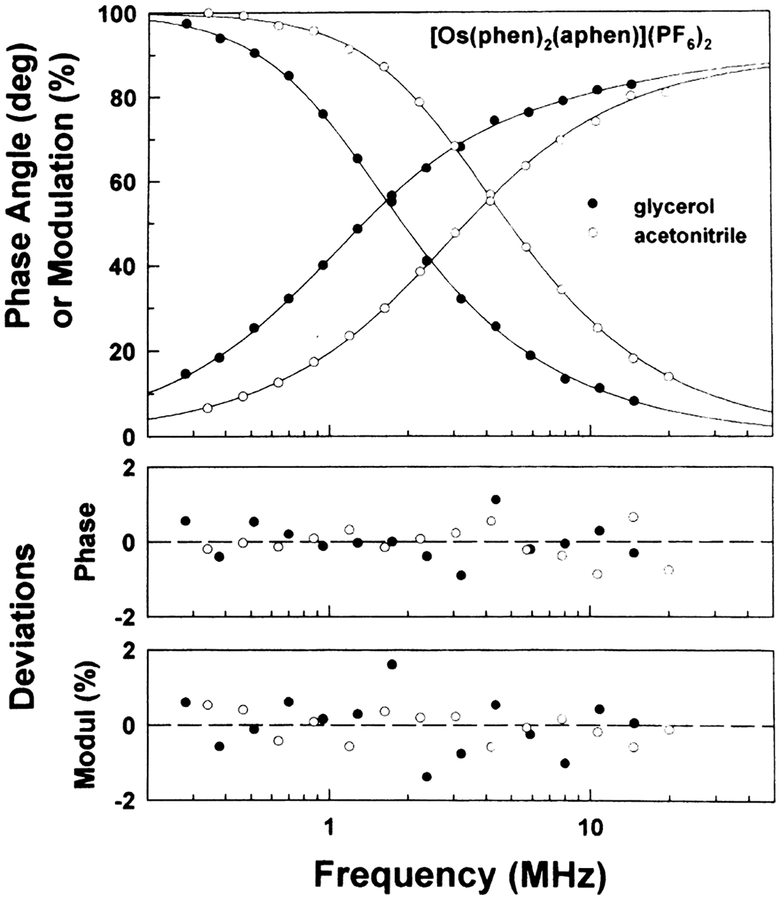

We examined the intensity decay of [Os-(phen)2(aphen)]2+ in solvents (Fig. 2) and in water (Fig. 3). The intensity decay was dominantly due to a 63-ns component, which increased to near 70 ns upon purging with argon to remove dissolved oxygen (Table 1, three decay time fits). A surprising result is the presence of a very long decay time component, 3300 ns in the presence of oxygen, and 11 000 ns in the absence of oxygen (Table 1). The contribution of this long component to the intensity decay is only 1.2% in the presence of dissolved oxygen, but increases to 12.4% in the absence of oxygen. The presence of this long lifetime component in the frequency-domain data can be seen by the modulation value below 0.9 frequencies below 1 MHz (Fig. 3). Because of this component four decay times were required to fit the data (Table 1). At present we do not understand the origin of this microsecond timescale component in the decay. Such long decay times are known for rhenium complexes which display ligand-centered phosphorescence [36–40], but we are not aware of any reports of ligand-centered phosphorescence from osmium complexes comparable to [Os(phen)2-(aphen)](PF6)2.

Fig. 2.

Frequency-domain intensity decay of [Os(phen)2-(aphen)](PF6)2 complex in glycerol (closed circles) and acetonitrile (opened circles), room temperature, air. The solid lines show the best single decay time fit in acetonitrile, and the best two-decay time fit in glycerol.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of frequency-domain intensity decay of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 in aerated (closed circles) and deoxygenated (opened circles) water solution in room temperature. The solid lines show the best three decay time fits to the data for the aerated sample, and the best four decay time fits for the deareated sample (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fluorescence decay of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2

| Solvent | τi (ns) | Δτia | αia | Δαia | fic | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | 56.4 | (0.4)a | 1.0e | 1.00 | 56.4 | 2.3b | |

| Glycerol | 138 | (2.0) | 1.0 | 1.00 | 138.0 | 16.4 | |

| 18.5 | (3.0) | 0.125 | (0.008) | 0.018 | |||

| 145.4 | (1.3) | 0.875 | (0.008) | 0.982 | 143.0 | 1.8 | |

| Water (air) | 61.8 | (0.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 61.8 | 5.71 | |

| 7.4 | (−2.3, +2.8) | 0.068 | (−0.009, +0.02) | 0.008 | |||

| 63.5 | (−0.7, +0.8) | 0.932 | (−0.02, +0.009) | 0.992 | 63.0 | 2.7 | |

| 6.8 | (−1.8, +2.4) | 0.064 | (−0.007, +0.011) | 0.007 | |||

| 62.9 | (0.6) | 0.936 | (−0.01, +0.005) | 0.981 | |||

| 3300.0 | (−2000.0, +30000.0) | 0.00022 | (−0.0002, +0.0005) | 0.012 | 102.0 | 2.3 | |

| Water (Ar) | 65.0 | (5.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 65.5 | 241.0 | |

| 61.0 | (3.0) | 0.998 | (−0.004, +0.02) | 0.852 | |||

| 5300.0 | (−3500.0, +62000) | 0.0020 | (−0.0002, +0.0004) | 0.148 | 838.0 | 72.1 | |

| 5.1 | (0.9) | 0.32 | (−0.01, +0.02) | 0.029 | |||

| 69.7 | (0.9) | 0.68 | (−0.02, +0.1) | 0.852 | |||

| 11 000.0 | (−3000.0,+ 7000.0) | 0.0006 | (−0.0002, + 0.003) | 0.119 | 1360.0 | 3.1 | |

| 2.7 | (−0.8, +0.6) | 0.36 | (−0.03, +0.05) | 0.019 | |||

| 58.0 | (−6.0, +3.0) | 0.52 | (−0.1, +0.06) | 0.593 | |||

| 112.0 | (20.0) | 0.12 | (−0.05, +0.08) | 0.264 | |||

| 21 000.0 | (−6000.,+ 11000.0) | 0.0003 | (0.0001) | 0.124 | 2660.0 | 1.4 | |

| BSA | 111.0 | (5.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 111.0 | 96.5 | |

| 26.0 | (2.0) | 0.38 | (0.02) | 0.100 | |||

| 143.0 | (−3.0, +4.0) | 0.62 | (0.02) | 0.900 | 131.0 | 5.3 | |

| 19. | (2.0) | 0.29 | (0.02) | 0.056 | |||

| 111.0 | (−8.0, +7.0) | 0.63 | (−0.05, +0.03) | 0.715 | |||

| 280.0 | (−40.0, +60.0) | 0.08 | (−0.04, +0.06) | 0.229 | 145.0 | 1.8 |

Standard deviations calculated by the Support plane or Bootstrap methods [34].

For experimental uncertainties δp = 0.3° and δm = 0.08.

Fractional fluorescence intensity.

Mean lifetime, .

Room temperature.

3.2. Spectral properties of Os(phen)2(aphen) — BSA

To determine the usefulness of this osmium complex it was covalently linked to bovine serum albumin. The amino form of the probe was converted to the isothiocyanate. The labeling procedure resulted in approximately one osmium complex bound per BSA molecule. The emission spectra and quantum yield of the labeled protein were comparable to that of the complex in glycerol.

The frequency-domain intensity decay of the label protein is shown in Fig. 4. The intensity decay was moderately heterogeneous, requiring three decay times for an adequate fit (Table 1). The intensity decay was dominantly due to a component with a decay time near 111 ns. The effect of dissolved oxygen was modest. Removing oxygen increases the intensity of the labeled protein by 6%.

Fig. 4.

Frequency-domain lifetime data of [Os(phen)2-(aphen)](PF6)2 covalently attached to BSA, 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 9.0). The solid line shows the best three-decay time fit to the data.

To characterize [Os(phen)2(aphen)]2+ as a hydrodynamic probe we measured the anisotropy decay of the labeled BSA (Fig. 5). The frequency-domain data were fit to the multi-correlation time model (Table 2). The anisotropy decay displays both a 40-ns component expected for overall rotational diffusion of the BSA, and a subnanosecond component typical of rapid motions of the probe attached to the protein. Approximately one-half of the anisotropy decays by each motion. Because of the low limiting anisotropy (0.12), and the rapid motions of the probe, the maximal differential phase angle is only 4°. While this was adequate to determine the rotational correlation time of BSA, a larger value of the fundamental anisotropy and less independent motions are desirable for an anisotropy probe.

Fig. 5.

Frequency-domain anisotropy decay measurements of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 covalently attached to BSA, 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 9.0).

Table 2.

Anisotropy decay of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 attached to BSA

| ϕi(ns)a,b | Δϕc | r0i | Δri | gi | Δgi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38.7 | (−1.1, +0.9)c | 0.07 | (−0.001, +0.001) | 1.0 | 2.11d | |

| 40.4 | (−0.3, +1.3) | 0.12 | (−0.04, +0.02) | 0.58 | (−0.11, +0.25) | |

| 0.23 | (−0.09, +0.73) | 0.42 | (−0.25, +0.11) | 1.84 |

[Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 in Tris 50 mM tris buffer (pH 9.0), room temperature.

Values calculated for triple exponential decay from Table 1.

Standard deviations calculated by the Monte Carlo method.

For experimental uncertainties δΔ = 0.3° and δΛ = 0.008.

4. Conclusions

[Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 was characterized as a luminescent probe. The mean decay time in solution and when coupled to proteins in over 100 ns. The long excitation and emission wavelengths allow excitation with simply solid-state light sources. The long lifetime will allow the use of gated detection to suppress the autofluorescence from biological samples. While the quantum yield of the osmium complex is rather low, osmium metal–ligand complexes are known to be extremely photostable [41,42]. Hence it should be possible to compensate for the low quantum yield by repeated pulsed illumination, even with highlight intensities, until the signal-to-noise is adequate for a given application.

The properties of [Os(phen)2(aphen)](PF6)2 as an anisotropy probe are adequate but not optimal. A higher fundamental anisotropy would be desirable, as would chemical coupling, which minimizes independent motions of the probe. In spite of these limitations this osmium probe does provide a considerable improvement over presently available long-wavelength probes in situations which require long decay times.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH National Center for Research Resources, RR-08119.

5. Nomenclature

- MLC

metal–ligand complex

- phen

1,10-phenanthroline

- aphen

5-amino-1, 10-phenanthroline

- FD

frequency-domain

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- FPI

fluorescence polarization immunoassay

- NIR

near infrared

References

- 1.Daehne S, Resch-Genger U, Wolfbeis OS, Near-infrared dyes for high technology applications, Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Syntheses, Optical Properties and Applications of Near-Infrared (NIR) Dyes in High Technology, Czech Republic, Kluwer Acad. Publishers, 1998, pp. 468. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casay GA, Shealy DB, Patonay G, Near-infrared fluorescence probes, in: Lakowicz JR(Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Probe Design and Chemical Sensing, vol. 4, Plenum Press, New York, 1994, pp. 183–222. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patonay G, Antonie MD, Near-infrared fluorogenic labels: New approach to an old problem, Anal. Chem 63 (1991) 321A–327A. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson RB, Red and near-infrared fluorometry, in: Lakowicz JR (Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Probe Design and Chemical Sensing, vol. 4, Plenum Press, New York, 1994, pp. 151–181. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JN, Brown MB, Seare NJ, Summerfield S, Analytical applications of very near-IR fluorimetry, in: Wolfbeis OS (Ed.), Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1993, pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Synthesis, spectral properties and photostabilities of symmetrical and unsymmetrical squaraines; a new class of fluorophores with long-wavelength excitation and emission, Anal. Chim 282 (1993) 633–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leznoff CC, Lever ABP, Phthalocyanines Properties and Applications, VCH Publishers, 1989, p. 436. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strickler SJ, Berg RA, Relationship between absorption intensity and fluorescence lifetime of molecules, J. Chem. Phys 37 (4) (1962) 814–822. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin RB, Richardson FS, Lanthanides as probes for calcium in biological systems, Q. Rev. Biophys 12 (2) (1979) 181–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horrocks W.DeW. Collier WE. Lanthanide ion luminescence probes. Measurement of distance between intrinsic protein fluorophores and bound metal ions: Quantitation of energy transfer between tryptophan and terbium (III) or europium (III) in the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin, J. Am. Chem. Soc 103 (1981) 2856–2862. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horrocks W.DeW. Sudnick DR. Lanthanide ion luminescence probes of the structure of biological macromolecules, Acc. Chem. Res 14 (1981) 384–392. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lövgren T, Pettersson K, Time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay, advantages and limitations, in: Van Dyke K, Van Dyke R(Eds.), Luminescence Immunoassay and Molecular Applications, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1990, p. 341. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soini E, Kojola H, Time-resolved fluorometer for lanthanide chelates — a new generation of non-isotropic immunoassays, Clin. Chem 29 (1983) 65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovgren T, Hemmila I, Pettersson K, Halonen P, Time-resolved fluorometry in immunoassay, in: Collins WP(Ed.), Alternative Immunoassays, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1985, pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamandis EP, Christopoulos TK, Europium chelate labels in time-resolved fluorescence immunoassays and DNA hybridization assays, Anal. Chem 62 (22) (1990) 1149–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lövgren T, Meriö L, Mitrunen K et al. , One-step all-in-one dry reagent immunoassays with fluorescent europium chelate label and time-resolved fluorescence, Clin. Chem 42 (8) (1996) 1196–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soini EJ, Pelliniemi LJ, Hemmilä IA, Mukkala V-M, Kankare JJ, Fröjdman K, Lanthanide chelates as new fluorochrome labels for cytochemistry, J. Histochem. Cytochem 36 (11) (1988) 1449–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurtubise RJ, Phosphorimetry: Theory, Instrumentation and Applications, VCH Publishers, Inc, New York, 1990, p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demas JN, DeGraff BA, Design and applications in highly luminescent transition metal complexes, in: Lakowicz JR(Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Probe Design and Chemical Sensing, vol. 4, Plenum Press, New York, 1994, pp. 71–107. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juris A, Balzani V, Barigelletti F, Campagna S, Belser P, Von Zelewsky A, Ru(II) polypyridine complexes: Photophysics, photochemistry, electrochemistry, and chemiluminescence, Coord. Chem. Rev 84 (1988) 85–277. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalyanasundaram K, Photochemistry of Polypyridine and Porphyrin Complexes, Academic Press, New York, 1992, p. 626. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Long-lifetime metal–ligand complexes as probes in biophysics and clinical chemistry, in: Brand L, Johnson ML(Eds.), Methods in Enzymology, Academic Press, 1997, pp. 295–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Malak H, Lakowicz JR, Metal–ligand complexes as a new class of long-lived fluorophores for protein hydrodynamics, Biophys. J 68 (1995) 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Fluorescence polarization immunoassay of a high molecular weight antigen based on a long-lifetime Ru-ligand complex, Anal. Biochem 227 (1995) 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caspar JV, Meyer TJ, Photochemistry of , J. Am. Chem. Soc 105 (1983) 5583–5590. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Fluorescence polarization immunoassay of a high-molecular weight antigen using a long wavelength-absorbing and laser diode excitable metal–ligand complex, Anal. Biochem 240 (1996) 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caspar JV, Kober EM, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ, Application of the energy gap law to the decay of charge-transfer excited states, J. Am. Chem. Soc 104 (1982) 630–632. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buckingham DA, Dwyer FP, Goodwin HA, Sargeson AM, Mono bis-(2,2′-bipyridine) and 1,10-(phenanthroline) chelates of ruthenium and osmium, Aust. J. Chem 17 (1964) 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kober EM, Casper JV, Lumpkin RS, Meyer TJ, Application of energy gap law to excited-state decay of Os(II)-polypyridine complexes, J. Phys. Chem 90 (1986) 3722–3734. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakowicz JR, Maliwal BP, Construction and performance of a variable frequency phase-modulation fluorometer, Biophys. Chem 21 (1983) 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy, in: Lakowicz JR(Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, vol. 1, Plenum Press, New York, 1991, pp. 293–355. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gratton E, Lakowicz JR, Maliwal B, Cherek H, Laczko G, Limkeman M, Resolution of mixtures of fluorophores using variable-frequency phase and modulation data, Biophys. J 46 (1984) 479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakowicz JR, Cherek H, Maliwal B, Laczko G, Gratton E, Determination of time-resolved fluorescence emission spectra and anisotropies of a fluorophore-protein complex using frequency-domain phase-modulation fluorometry, J. Biol. Chem 259 (1984) 10967–10972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson ML, Evaluation and propagation of confidence intervals in nonlinear, asymmetrical variance spaces: analysis of ligand binding data, Biophy. J 44 (1983) 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakowicz JR, Cherek H, Kusba J, Gryczynski I, Johnson ML, Review of fluorescence anisotropy decay analysis by frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy, J. Fluoresc 3 (1993) 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo X-Q, Castellano FN, Li L, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Sipior J, A long-lived, highly luminescent Re(I) metal–ligand complex as a biomolecular probe, Anal. Biochem 254 (1997) 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo X-Q, Castellano FN, Li L, Lakowicz JR, Use of a long-lifetime Re(I) complex in fluorescence polarization immunoassays of high-molecular weight analytes, Anal. Chem 70 (1998) 632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baba AI, Shaw JR, Simon JA, Thummel RP, Schmehl RH, The photophysical behavior of d6 complexes having nearly isoenergetic MLCT and ligand localized excited states, Coord. Chem. Rev 171 (1998) 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoeffler HD, Thornton NB, Temkin SL, Schanze KS, Unusual photophysics of a rhenium(I) dipyridophenazine complex in homogenous solution and bound to DNA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 117 (1995) 7119–7128. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw JR, Schmehl RH, Photophysical properties of Re(I) diimine complexes: Observation of room-temperature intraligand phosphorescence, J. Am. Chem. Soc 113 (2) (1991) 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen G, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lever ABP, Inorganic Electronic Spectroscopy, Elsevier, New York, 1968. [Google Scholar]