Abstract

We examined the relationship between white matter hyperintensities (WMH) burden and performance on four reference abilities (RAs): episodic memory, perceptual speed, fluid reasoning, and vocabulary. Cross-sectional data of 486 healthy adults from 20 to 80 years old enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study were analyzed. A piecewise regression across age identified an inflection point at age 43 years old, where WMH total volume began to increase with age. Subsequent analyses focused on participants above that age (N = 351). WMH total volume had significant inverse correlations with perceptual speed and memory. Regional measures of WMH showed inverse correlations with all RAs. We performed principal component analysis of the regional WMH data to create a model of principal components regression (PCR).

Parietal WMH regional volume burden mediated the relationship between age and perceptual speed in simple and multiple mediation models. The PCR pattern associated with perceptual speed also mediated the relationship between age and perceptual speed performance.

These results across the extended adult lifespan help clarify the influence of WMH on cognitive aging.

1. Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMH), which are distributed patches of augmented lucency (bright signal) on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are a common finding in brain scans of older people (Longstreth et al., 1996; van Dijk et al., 2002). Clinically, there is evidence that WMH are associated with cognitive decline and may have a role in the etiology of dementia (Brickman et al., 2009; de Groot et al., 2001; De Groot et al., 2002; De Leeuw et al., 2001; DeCarli et al., 2005; Frisoni et al., 2007; Iadecola, 2013; Yoshita et al., 2006). However, in the clinical setting, WMH are often seen as benign comorbidity of aging due to their very high prevalence in older adults (Lindemer et al., 2017b, 2017a).

To better understand the impact of WMH in the aging brain, it is important to explore their association with cognitive domains that are affected by aging and dementia. For example, Breteler et al reported that periventricular WMH, brain infarcts and generalized brain atrophy on MRI are associated with the rate of decline in processing speed and executive function (Prins et al., 2005). In addition, it is important to consider the localization of WMH. For example, it has been reported that parietal WMH are associated with a higher risk of developing Alzheimer Disease (AD), (Brickman et al., 2015, 2012) while frontal WMH are associated with higher risk of mortality (Wiegman et al., 2013). In samples of community-dwelling middle-age adults, specific brain loci (clusters) of WMH burden were inversely correlated with episodic memory (Smith et al., 2011) and executive function. (Smith et al., 2011)

In the present paper, we first used a piecewise regression across age to establish an inflection point where WMH burden increased systematically and limited our analysis to above that age. We focused on the relationship between WMH burden and performance on four cognitive domains, or reference abilities (RAs), that capture most of the age-related variance in cognitive performance (Salthouse, 2005). Lastly, we used mediation models to explore whether WMH mediated the relationship between the effects of age and each RA. In healthy adults age 20–80, we explored the patterns of regional WMH burden that best predicted cognitive performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Data for the present study were collected in two ongoing projects – the Reference Ability Neural Networks (RANN) and the Cognitive Reserve (CR) studies. The RANN study was designed to identify neural networks associated with cognitive performance throughout the lifespan of a healthy sample in the four previously mentioned reference abilities (RAs): episodic memory, perceptual speed, fluid reasoning, and vocabulary (Salthouse, 2009). The CR study aims to elucidate the neural underpinnings of cognitive reserve and clarify the concept of brain reserve from a neuroimaging perspective (Stern, 2012). Detailed information about the two studies is provided in the previous publications (Habeck et al., 2016; Stern, 2012; Stern et al., 2014). Only the WMH neuroimaging data and neuropsychological test scores from these studies were used in the current study.

This study uses data from cognitively healthy adults between 18 and 80 years old. Recruitment was done using a random market mailing procedure within 10 miles of the Columbia University Medical Center. This recruitment approach intends to obviate cohort effects that might be present by using convenience samples. Participants were telephone screened as the first part of the recruitment process. The screening phase checked the basic inclusion criteria which included being right-handed, native English speaker, have at least fourth grade reading level. If the participants passed the first level of screening, they underwent an in-person assessment. Older subjects were screened to insure they did not meet criteria for dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and had a score greater than 130 on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (Mattis, 1988). Other exclusion criteria were: any psychiatric history, namely psychosis, recent (past five years) major depressive, bipolar, or anxiety disorders, electroconvulsive therapy treatment (ECT), alcohol or drug abuse within the last 12 months; cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure or any other cardiovascular disease; neurological disorders such as stroke, tumor, central nervous system infection, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, degenerative diseases, head injury (loss of consciousness > 5 mins), mental retardation, seizure, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus, essential/familial tremor, untreated neurosyphilis, Down Syndrome; uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or insulin dependent diabetes, uncontrolled thyroid or other endocrine disease; uncorrectable vision, color blindness, uncorrectable hearing and implant; pregnancy, lactating; any medication targeting central nervous system; oncological disease within the last five years; renal insufficiency and/or active hepatic disease. No participant was excluded based on his or her WMH volume.

The Institutional Review Board of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University approved the study. The consent form was obtained prior to study participation, and after the nature and risks of the study were explained. All subjects received compensation for their participation.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Reference abilities

Based on a previous principal axis factor analysis (Salthouse et al., 2015), a composite score for each of the RAs was obtained using measures from a battery of well-established neuropsychological instruments. Z-scores were calculated for each cognitive task. For each RA (representing a cognitive domain), a summary score was calculated by averaging the three z-scores. Higher scores indicate better performance. The four domains include the following tests:

Fluid reasoning:

This composite score was based on three tests, the WAIS-III Block Design test, (Wechsler, 1997) in which participants are asked to reproduce a series of increasingly complex geometrical shapes using 4 or 9 identical blocks with red, white, or split red and white sides; WAIS-III Letter-number Sequencing (Wechsler, 1997) in which participants are asked to recall progressively longer lists of intermixed letters and numbers first in alphabetical and then numerical order; and WAIS-III Progressive Matrices in which participants are asked to select which pattern in a set of eight possible patterns best completes a missing cell in a matrix.

Vocabulary:

The composite score was based on the vocabulary subtest from the WAIS-R (Wechsler, 1997), which asks participants to provide definitions for series of increasingly more complex words, as well as the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) (Wechsler, 2001) and the American National Adult Reading Test (AMNART) (Grober and Sliwinski, 1991) that both involve pronouncing irregularly spelled English words.

Episodic memory:

The composite score was based on three subscores obtained through Selective Reminding Test (SRT). In this task, participants initially read a list of 12 words and were asked to recall as many as they could. For the following five trials, they were reminded of the words that they did not report and were asked to again recall all the words in the list. Words are considered to enter long-term storage from the point when they are recalled twice in a row without reminders. The subscores used are Long Term Storage Subscore (SRT LTS), the sum of all words recalled at least twice in a row, Consistent Long-term Retrieval (SRT CLRT), the sum of all words that are consistently recalled, finally, Last Trial (SRT Last) which is the number of words recalled on the last trial of the test. (Buschke and Fuld, 1974).

Perceptual speed:

The composite score was based on the three different tests, the WAIS-III Digit-symbol subtest (Wechsler, 1997), where participants were instructed to draw the symbol corresponding to a specific number as quickly as possible, the score is the number of correctly produced symbols in 90 seconds; Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A, where participants were asked to connect circles numbered from one to 24 as rapidly as possible, the score is the time to connect all 24 circles. (Reitan, 1958); Stroop Color Naming test, where the participants were asked to identify the colored ink patches, the score is the number of color ink patches named in 45 seconds. (Golden, 1978).

2.3. Imaging procedures

2.3.1. MRI acquisition and image processing

All images were acquired on the same 3.0 T Philips Achieva Magnet. A coronal T1-weighted (T1W) MPRAGE scan was used to determine the participant’s position. Parameters for the EPI acquisition included the following: 3 msec for the T1W repetition time (TR), 6.5 msec echo time (TE), 8° deg flip angle, 256 × 200 voxels in-plane resolution and 165–180 slices in the axial direction with slice-thickness/gap of 1/0 mm.

In addition, a FLAIR scan was acquired with the following parameters: 11 000 msec TR, 2800 msec TE, 256 × 189 voxels in-plane resolution, 23.0 × 17.96 cm field of view (FOV), and 30 slices with slice-thickness/gap of 4/0.5 mm. This sequence was used to quantify the WMHs volumes. A neuroradiologist reviewed each scan individually to exclude any relevant findings. In the case of a clinical positive finding, the subject’s primary care physician was informed.

2.3.2. Image Processing

Structural T1 scans were reconstructed using FreeSurfer v5.1 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). The accuracy of FreeSurfer’s subcortical segmentation and cortical parcellation has been reported to be comparable to manual labeling (Desikan et al., 2006; Fischl et al., 2002). Each participant’s boundaries of white and gray matter, as well as gray matter and cerebral-spinal-fluid boundaries, were visually inspected slice by slice, and manual control points were added in case of any visible discrepancy. Boundary reconstruction was repeated until reaching optimized results for every participant. The subcortical structure borders were plotted by Freeview visualization tools and manually reviewed. In the case of discrepancy, the manual correction was done. Lastly, we computed mean values for white matter cortical volumes and intracranial volumes (ICV) for each participant.

2.3.3. Automatic WMH (total volumes) segmentation, classification, and quantification

WMH were segmented by the Lesion Segmentation Tool algorithm (LST) (P. et al., 2011) as implemented in the LST toolbox version 2.0.15 (June 2017) for Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) (www.statistical-modelling.de/lst.html). The algorithm first segments the T1 images into the three main tissue classes – cerebral brain fluid (CSF), grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM). Then, this information is combined with the co-registered FLAIR intensities in order to calculate lesion belief maps. By thresholding these maps with a pre-chosen initial threshold (κ=0.5), an initial binary lesion map is obtained which is subsequently grown along voxels that appear hyperintense in the FLAIR image. The result is a lesion probability map. Every FLAIR sequence that had a total WMH volume above 1000 mm3 was manually inspected to ensure that there were no visible discrepancies.

2.3.4. Extraction of regional WMH volumes

To extract lobar WMH values, we first registered the T1 sequence of each participant in FreeSurfer and then co-registered the FLAIR sequence. The following lobar regions, frontal, parietal, temporal, cingulate and occipital, were defined as the lobes in FreeSurfer. The volumes of WMH in each of the five lobes were automatically extracted. One participant was excluded due to technical problems in extracting the regional WMH map.

3. Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analyses in R 3.14.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing), using base functions and mediation package. MATLAB R2017a, MathWorks, Natick, was used for the principal component analysis and principal component regression. Descriptive statistics were calculated, including means and standard deviations, minimum and maximum absolute values, frequency counts and percentage for demographic and neuropsychological variables, and median and interquartile range for the neuroimaging variables. We used two-tailed significance tests and p-values less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. To reduce skewness, WMH values were transformed using an inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS). This transformation is used to reduce the influence of extreme observations and behaves like the logarithmic transformation for large enough values, regardless of its parameter value 0 (as long as it does not equal 0) (Burbidge et al., 1988).

To account for zero inflated distribution, we considered a two-part model (Belotti et al., 2015) using logistic regression to model having WMHI burden and log-normal regression to model the distribution of WMHI when it is greater than zero. Given the hypothesized nonlinear relationship between age and WMH (total and regional volumes), we used a piecewise regression model (also called “broken stick” model) to study the trend of this relationship. We employed this model with an inflection point as a parameter. This regression model is often used when it is assumed that after a certain lag the response increases or decreases linearly, starting from the baseline value. This assumption reflects a model in which the first part is a horizontal line (McGee and Carleton, 1970). In piecewise linear regression, the inflection point was selected using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to test whether the inclusion of the inflection point significantly improved the model fit, compared with the model without the inflection point (Piepho and Ogutu, 2003). All the subsequent analysis considered only ages above the calculated inflection point.

To explore the relationship between WMH (regional and total volumes) and the four RAs, we performed two different sets of linear regression models. First, we separately fit a linear regression model for each of the four RAs (as the dependent variable) with age and total WMH as independent variables. Secondly, we fit linear regression models for each of the four RAs (as the dependent variable) with age and the five regional WMH as independent variables. Education (in years), gender and ICV were entered as covariates in the above-explained models.

We then applied principal components analysis (PCA) and principal components regression (PCR) to the WMH values in the five lobes. More details about this multivariate decomposition technique can be found in Lee et al. (Lee et al., 2016) and Habeck et al. (Habeck et al., 2008). The consideration of these techniques in this data reduces the chances of collinearities. We derived a covariance pattern, consisting of a set of principal components (PCs) that best predicted performance in each RA. We excluded one individual that had a volume of 0 mm3 of WMH in all five lobes. The procedure was as follows:

Derive a PCA on the data of the five WMH regional volumes (IHS transformed) across all subjects with age above the inflection point. Each lobe (representing the WMH burden in that region) in each principal component (PC) may have either a positive or a negative loading. These loadings are fixed and the same for all subjects. The expression of each PC for each subject was quantified by a subject-scaling factor (SSF) or the “individual PC expression score”. Therefore, the SSF express the degree of subjects’ expression of the fixed PC. To find a covariance pattern that best discriminates cognitive performance in each of the RAs, each subject’s expression of the specified PC derived from step 1 was entered into a linear regression model as the independent variable. Each RA individually was the dependent variable. This regression results in a linear combination of the PC that best predicts cognitive performance. This linear combination of the PC can itself be conceived as signifying a ‘pattern’ of WMH distribution. We used Akaike’s information criterion to decide how many PCs should be included in the regression in order to achieve optimal bias-variance trade-off. The set of PCs that yields the lowest value in Akaike’s information criterion was selected as predictors in the regression model. We did not restrict the number of PCs, so we checked the following sets: PC1, PC1–2, PC1–3, PC1–4, PC1–5. PC1 was always included because combinations excluding PC1 had very small variance contributions and failed to show robust-enough loadings in the bootstrap procedure. The set that yielded the lowest value of Akaike information criterion (AIC) was selected for construction of the discriminant pattern. For the pattern construction, after the optimal subset is selected, we took the regression weights for all the chosen components and constructed a corresponding pattern, which assigned a loading to each regional volume. For the bootstrap estimation of loading robustness, we performed a bootstrap resampling test with 10,000 iterations, meaning that each time we resampled the pool of subjects with replacement and repeated our analysis for the specific PC-set picked in the point estimate computation. For each lobe, the 95% confidence interval (CI) was listed. This procedure provided information on the stability of the contribution from each WMH regional volume towards the covariance pattern. If the 95% CI did not include the zero point, the loading can be interpreted as stable. We did not account for the possible nonlinear association between variables in this analysis.

Finally, we tested a formal mediation model between age, WMH total volume and each of the four RAs. We started the mediation analysis by testing whether the primary independent variable, in this case age, predicted the dependent measure of each of the four RAs. Next, we tested the direct effects of age on the mediator (WMH total volume) and the direct relationship between the mediator, WMH total volume and the dependent variable (cognition, as measured by the RA). Then we tested the indirect mediating effect or the extent to which the relationship between age and each of the four RAs has WMH total volume as a mediator. We hypothesized that there is a mediating effect of each regional WMH in the relationship between age and each of the four RAs. After running the model for WMH total volume we also re-ran a mediation model with each of the regional WMH volumes as the mediators. Finally, we tested a mediation model using the five regional WMH volumes as multiple mediators and controlling for education. Lastly, we tested a mediation model using PC derived patterns.

4. Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon request.

5. Results

5.1. Demographics

The total sample (from 20 to 80 years old) included 486 healthy adults that had the T1 and FLAIR scans. 468 completed the neuropsychological evaluation and 464 completed the memory tasks. The excluded participants could not complete the neuropsychological evaluation. Table 1 contains the sociodemographic characteristics, neuropsychological scores and the MRI data of the participants included in the analysis.

Table 1. Demographic, neuropsychological and imaging data.

For all demographic and neuropsychological variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) are shown, except for gender (presented as a percentage of women). For imaging variables median and interquartile range are presented. NARTIQ = National Adult Reading Test Intelligence Quotient; WMH = White matter hyperintensities. WMH total volume has an n = 485. *All reference abilities have an n=468 except for episodic memory where it is 464. ** Regional WMH volume burden has an n=350.

| Total Sample (n = 486) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Min-max | Mean (SD) |

| 53.69 (16.78) | 20.00 – 80.00 | 62.82 (8.77) |

| 56.2 | - | 67.1 |

| 16.16 (2.37) | 9.00 – 24.00 | 16.26 (2.40) |

| 117.07 (8.73) | 85.28 – 130.88 | 118.89 (8.46) |

| 0.02 (0.82) | −1.93 – 2.17 | −0.17 (0.74) |

| 0.03 (0.92) | −2.86 – 1.28 | −0.19 (0.91) |

| 0.02 (0.93) | −2.50 – 1.64 | 0.16 (0.88) |

| 0.00 (0.83) | −3.22 – 2.19 | −0.22 (0.74) |

| Median (Interquartile range) | ||

| 114.50 (690.00) | 0.00 – 51917.0 | 310.00 (1735.99) |

| 5.43 (4.44) | 0.00 – 11.55 | 6.43 (3.66) |

| 462198.31 (73841.00) | 304556 – 680077 | 458257.28 (73834.57) |

| 1475467.00 (197260.00) | 1042703 −1900961 | 1473744.50 (198505.2) |

| 0.00 (1.21) | 0.00 – 4.20 | 0.00 (1.77) |

| 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 – 3.26 | 0.00 (0.00) |

| 1.21 (2.23) | 0.00 – 3.46 | 1.61 (2.40) |

| 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 – 3.21 | 0.00 (0.38) |

| 0.00 (1.30) | 0.00 – 3.76 | 0.00 (1.72) |

5.2. The relationship between age and WMH total volume – piecewise linear regression

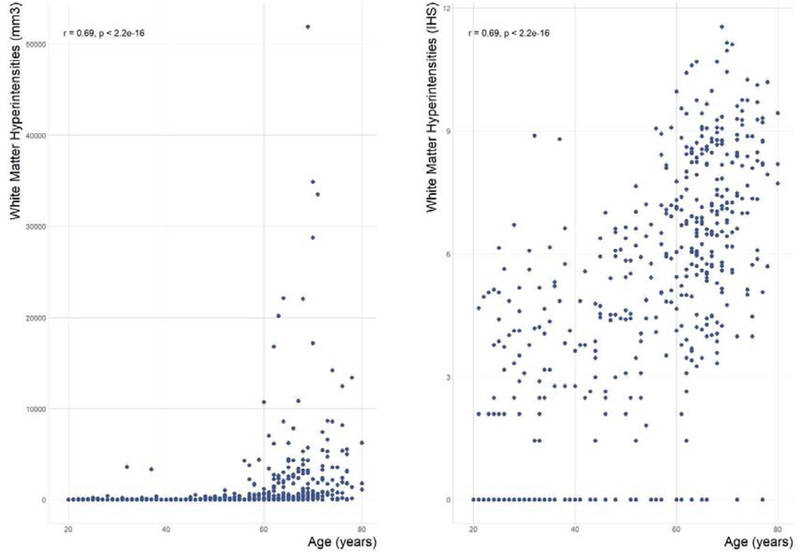

Figure 1 shows the relationship between WMH (total volume) and age for each individual included in the present study (n = 486). The Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient between age and WMH total volume was 0.69 (p < 0.0001). Broadly, volumes larger than 1000 mm3 appear after 40 years old of age, becoming increasingly larger for subjects above 50 years old. In fact, the relationship between WMH total volume before the age of 43 was closer to a horizontal line and after 43 years old this trend changes.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots for the relationship between age and white matter hyperintensities (WMH) total volume. In the right plot, the WMH total volume is represented as raw mm3 volume and in the left plot is represented using inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) transformation. Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient was used as a correlation measure. The arrow shows the inflection point obtained in the piecewise linear regression. r = Spearman’s rho (n = 486). Before inflection point (Age<43), we did not find any association (β1=0.16, p=0.76), while after infection point, WMHI was significantly associated with age (β2=4.52; p<0.0001)

We fitted a piecewise regression model to better address the nonlinear trend of the association between age and WMH total volume. This model estimated the existence of one inflection point at 43 years of age (95% CI between 24.35 and 59.10 years old). After determining the inflection point where the relationship between WMH total volume and age becomes closer to linearity, we restricted all subsequent analyses to participants above age 43.

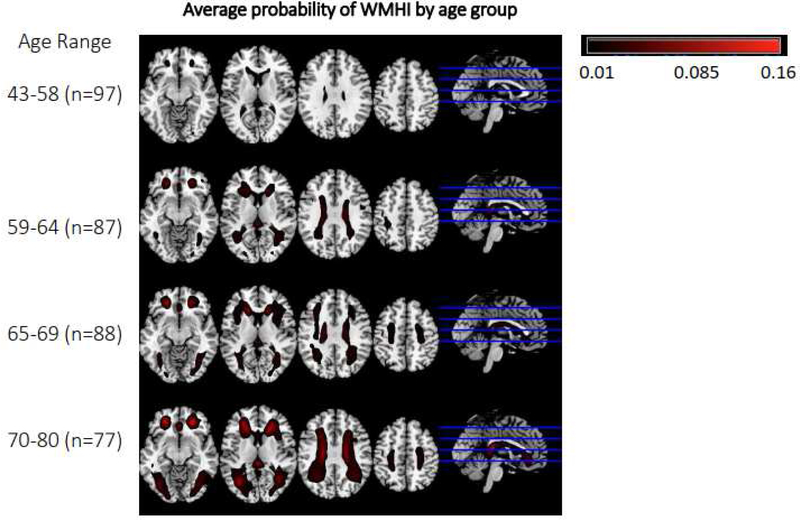

Figure 2 shows the average probability of having WMH in four age groups. The probability increases with age and it is higher in the 70–80 years old.

Figure 2.

Probability of having WMH in the different age groups above 43 years old.

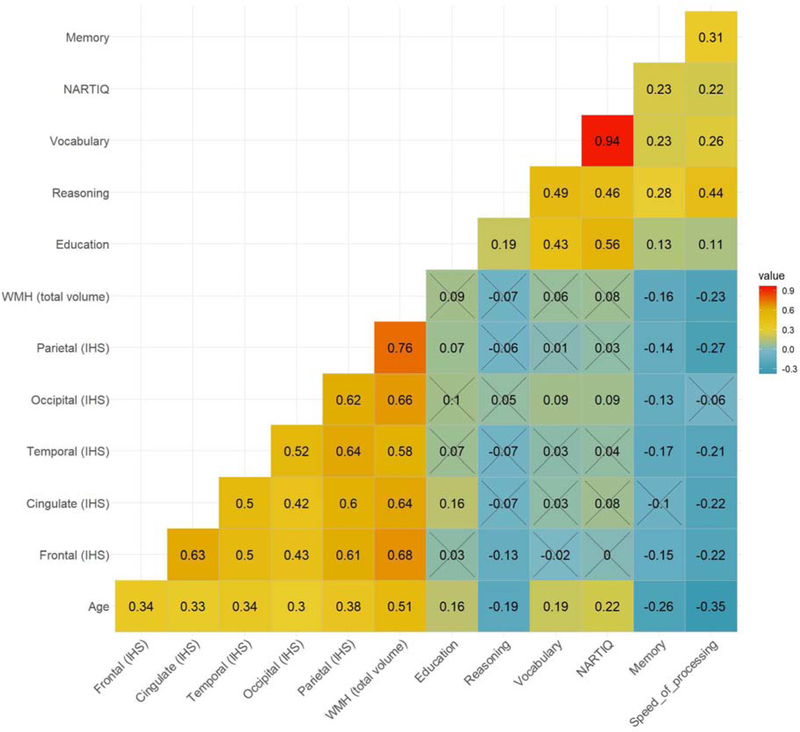

5.3. Correlation of age, cognition, and WMH (total and regional volumes)

Figure 3 shows the correlation matrix for the variables of interest using Spearman’s rank-order correlation. The sample included participants with or above 43 years old (N = 351). As expected, we found a moderate to a strong positive correlation between age and WMH total volume (spearman’s rho = 0.51, p < 0.001). WMH total volume had weak significantly inverse correlations with speed of processing (spearman’s rho = − 0.23, p < 0.001) and memory (spearman’s rho = −0.16 p < 0.001). Regional measures of WMH showed weak inverse correlations with each of the four RAs, being the highest between parietal regional WMH and speed of processing RA (spearman’s rho = − 0.27, p < 0.001). Additionally, the five-regional lobar WMH had significant positive correlations among themselves.

Figure 3. Correlation matrix for age, education, white matter hyperintensities (WMH) total and regional volumes and the four reference abilities (RAs) using a sample above 43 years old.

Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient was used as a correlation measure. All results are significant (p < 0.05), except where the crosses are shown that are non-significant. Speed_of_processing = speed of processing RA; Reasoning = Fluid reasoning RA; Memory = Episodic memory RA, Vocabulary = Vocabulary RA; NARTIQ = American National Adult Reading Test (z-score); Education = years of education; WMH (total volume) = White matter hyperintensities total volume IHS; Parietal_IHS = White matter hyperintensities total volume (IHS-transformed) in the parietal lobe; Occipital_IHS = White matter hyperintensities total volume (IHS-transformed) in the occipital lobe; Temporal_IHS = White matter hyperintensities total volume (log-transformed) in the temporal lobe; Cingulate_IHS = White matter hyperintensities total volume (IHS-transformed) in the cingulate lobe; Frontal_IHS = White matter hyperintensities total volume (IHS-transformed) in the frontal lobe.

5.4. The relationship between age, WMH total and regional volumes and cognition

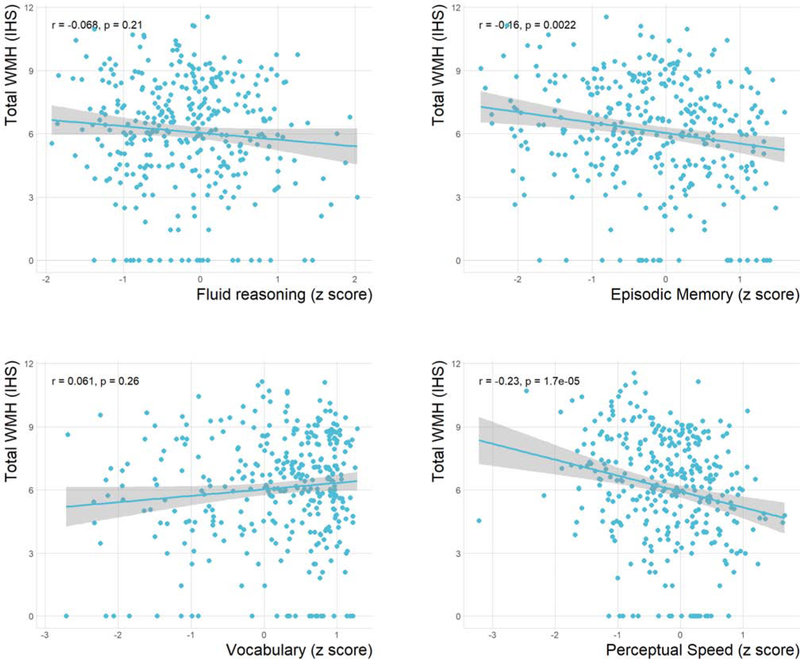

Figure 4 shows the correlation of WMH total volume with each of the four RAs. Simple linear regression models revealed significant associations between each of the four RAs and WMH (see supplementary table 1). When age was entered into the model, the associations lost their significance as depicted in supplementary table 2. Supplementary table 3 contains the parameter estimates for the first four regression models with age and education as covariates. We re-ran these models controlling also for gender and ICV and similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Figure 4. Scatter plots of the relationship between each of the four reference abilities (RAs) and white matter hyperintensities (WMH) total volume.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used as a correlation measure. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval around the regression line. r = Spearman’s rho.

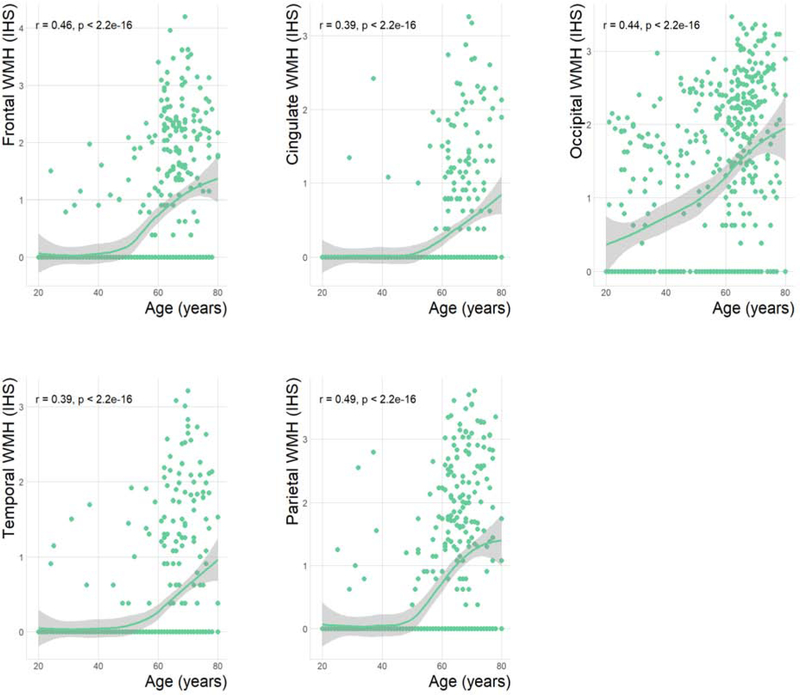

Scatter plots showing the relationship between age and each of the five WMH regional volumes are shown in figure 5. All the correlation coefficients are positive (p-values <0.001). In general, WMH volumes larger than 1 (IHS) appear after the fourth decade of life and became increasingly large after that age. The Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient between WMH total volume in lobar regions and age (above 43 years old) were frontal 0.46 (p < 0.0001), cingulate 0.39 (p < 0.0001), occipital 0.44 (p < 0.0001), temporal 0.39 (p < 0.0001) and parietal 0.49 (p < 0.0001). Supplementary table 4 reports the associations between the five regional WMH volumes and the four RAs in four separate linear regression models using all regional WMH volumes as independent variables and each RA as the dependent variable. Age and education were entered in the model as covariates and accounted for most of the significance in the predictions that were obtained (supplementary table 5).

Figure 5. Scatterplots of the relationship between age and regional WMH volumes in each of the five lobes (frontal, cingulate, occipital, temporal and parietal).

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used as a correlation measure. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval around the regression line. r = Spearman’s rho. All correlation remained significant after multiple comparison correction.

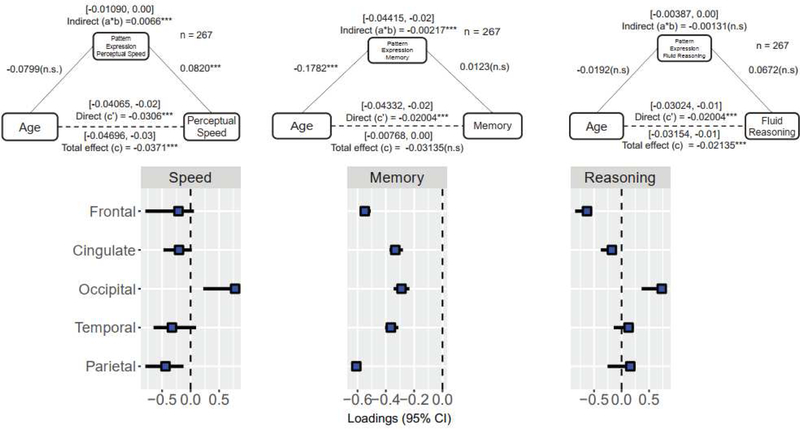

5.5. PCA between regional WMH and RAs

We performed PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the regional WMH data. Loadings for each WMH region were extracted for each PC. Loadings and point estimates of PC1 – 4 can be seen in supplementary table 6. The first PC accounts for 64.58% of the data variance and the second for the next 16.13%. Loadings were normalized for all PCs to have a Euclidean norm = 1. The first PC showed negative loadings in all WMH regions. The second PC showed negative loadings in all WMH regions except in the occipital lobe. These PCs loadings are presented in table 6 of the supplementary material.

We applied a model of PCR using the obtained PCs to predict each RA separately. For perceptual speed, the model that best predicted cognitive performance consists of three PCs. The best model to predict episodic memory across subjects used only the first PC. For fluid reasoning RA, the model best predicting the data variance used the first two PCs. For vocabulary, we did not find a significance in any of the models using up to the five PCs.

5.6. Mediation models

We tested whether WMH mediated between age and cognition. We did not find a mediation effect using WMH total volume. We assessed mediation of each of the five regional WMH total volumes and found a significant mediating effect of parietal regional WMH in the relationship between age and perceptual speed (supplementary table 7). No mediation was seen for the other RAs. We then tested multiple mediation models, simultaneously including all five regional WMHI volumes and controlling for education. In this model, parietal WMH volume mediated approximately 25% of the relation between age and perceptual speed while occipital WMH had suppression effect. The results of this mediation model can be seen in table 2. Again, there were no multiple mediating effects for the other RAs (supplementary table 8 and 9). We also tested the mediation effect of each pattern of PCR and found that only the pattern for perceptual speed had a significant mediating effect in the relationship between age and perceptual speed, as seen in figure 6 (and in supplementary table 10).

Table 2. Parameter estimates for multiple mediating effects of WMH regional volumes in the relation between age and Perceptual Speed.

The model represents the adjusted total, indirect and direct effects of WMH regional volumes. The 95% confidence intervals of total, direct and indirect effect were estimated from 10 000 bootstrapped samples. The analysis was run in participants above 43 years old. WMH = white matter hyperintensities, SE = Standard error; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. *Bonferroni corrected p-value <0.05.

| Effect | Region | Estimate | S.E. | z | P value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | - | −0.02889 | 0.0042 | −6.82 | <0.0001* | −0.0372 | −0.0208 |

| Direct | - | −0.02448 | 0.0044 | −5.54 | <0.0001* | −0.0334 | −0.0159 |

| Indirect (a*b) | Frontal | −0.00153 | 0.0021 | −0.74 | 0.46 | −0.0056 | 0.0026 |

| Cingulate | −0.00135 | 0.0016 | −0.82 | 0.41 | −0.0046 | 0.0019 | |

| Occipital | 0.00515 | 0.0018 | 2.92 | 0.0035* | 0.0022 | 0.0090 | |

| Temporal | 0.00028 | 0.0019 | 0.15 | 0.88 | −0.0034 | 0.0043 | |

| Parietal | −0.00696 | 0.0027 | −2.60 | 0.0092* | −0.0124 | −0.0020 | |

Figure 6. Mediation models of the principal components regression (PCR) patterns in the relation between age and perceptual speed, memory and fluid reasoning.

Each diagram represents the mediation models adjusted for total, indirect and direct effects of the models. The 95% confidence intervals of total, direct and indirect effect were estimated from 1000 bootstrapped samples. The analysis was run in participants above 43 years old. WMH = white matter hyperintensities; SE = Standard error; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

6. Discussion

In this study, we report three important findings. Firstly, the estimation of an inflection point where the relationship between age and WMH changes. The second is the relationship between total and regional WMH, as well as, a simultaneous combination of WMH five lobar regions, with cognition. The strongest model was for the prediction of perceptual speed; we found a significant prediction of fluid reasoning and memory but not vocabulary. These relationships were not seen after controlling for age. Third, we found that the parietal regional burden of WMH mediated the relationship between age and perceptual speed RA.

Our study adds information to the growing body of the literature on WMH by describing the prevalence of these common neuroimaging findings across the human lifespan. c (Huang et al., 2018). In our larger sample of individuals, with ages across the entire adult lifespan, we found that around 43 years of age there appears to be a modification in the relationship between age and the WMH total volume. The finding of an inflection point in a relatively young age converges with the growing evidence of the need to assess components of the ageing process starting much earlier than the typical age of onset of neurodegenerative diseases (Debette, S. Seshadri, A. Beiser, R. Au, J.J. Himali, C. Palumbo, 2011). This finding also underscores the importance of sampling a wide age range when studying the aging brain. The study of age-related changes in the brain using only older participants increases the chance of missing important nonlinear trends (Raz et al., 2005). There is extensive literature reporting a higher rate of decline with aging in some neuroimaging measures including cortical thickness (Raz et al., 2005), (Draganski et al., 2013), brain volume (Raz et al., 2005) and white matter tract integrity (Booth et al., 2013),. Our cross-sectional observation adds information regarding WMH to these previous reports. Other authors had proposed the age range of mid-fifties as a likely decade where the point of inflection for some neuroimaging indices, but without formal testing of this hypothesis (Huang et al., 2018; Raz et al., 2005). We estimated an inflection point in where there is a change in the volume of the WMH, observing virtually no extensive WMH burden in young adulthood. This finding may play a vital role, as WMH may be an important biomarker of pathologic changes in aging and disease (Salat et al., 2009).

Cognitive measures are key to unpacking subtle variations between normal cognitive aging and subclinical neurodegenerative processes. While neuropsychological measures used in most studies are well-validated and quick to administer, typically they lack the specificity to dissect age-related cognitive processes (Salthouse et al., 2015). Therefore, individual neuropsychological tests, have limited use for investigating the direct effect of age on a cognitive phenotype. Numerous studies have assessed the effect of WMH using different sets of neuropsychological batteries, regardless of the association of the cognitive domains with age. A more selective assessment of cognitive domains may be advantageous, in the context of the study of aging and age-related neuroimaging findings. Indeed, the RA construct presents as a very robust method to address cognitive variation across the lifespan specifically in older adults, since these four reference abilities have been demonstrated to capture most of the age-related variance in cognition. One of the main strengths of our approach is, thus, a comprehensive assessment of brain function using neuropsychological constructs which are proposed to be better suited to capture cognitive aging (Salthouse, 2009).

While we noted robust correlations between WMH total burden and cognition, these relationships were no longer significant after controlling for age. Because age and WMH burden is so strongly correlated, it is difficult to determine the unique effect of WMH on cognition in this context. Thus, the mediation models were of great importance, since they assess whether the effect of age on cognition may be mediated by WMH. We evaluated the impact of the regional distribution of WMH on specific cognitive domains by using a mediation model to study the effect of total and regional WMH on the four RAs individually. Interestingly, we found that the WMH total volume alone did not mediate the relationship between age and each of the RAs. Rather, we found that parietal WMH regional volume mediated the association between age and worse performance in perceptual speed. When all regions were entered in the mediation model, parietal WMH still contributed significantly, but a suppression effect was noted for occipital WMH. Since occipital WMH volume did not mediate on its own, we attribute this suppression effect to some artifact of the multiple variables included in the regression. One possibility is that different age trajectory of the occipital lobe WMH burden contributed to this result. This should be followed up in an independent data set. Previous literature had observed a mediating effect between age, WMH total volume, brain atrophy and global measures of cognition. The present study further explores the cognitive implications of WMH in specific cognitive domains.

From a methodological perspective, canonical correlation, PCR and its variants (such as partial least squares correlation) can be used in neuroimaging studies to explore structural MRI findings. Our approach was a direct application of this method using a PCR to evaluate the relationship of regional WMH to each of the four RAs. The method was tuned using feature selection in order to optimize the prediction of RA scores using the five regional WMH volumes. This technique improves on simple multiple linear regression because it accounts for correlation patterns between the independent variables. This methodology provides a unique contribution to the literature because it is one of the first attempts to study the relationship between the different regions where WMH appear and their specific relationship with cognition. In the present study, we found selective associations between WMH regional volumes and specific RAs. Perceptual speed provided the best model and it was derived using a linear combination of PCs 1–3, implying a negative relationship between speed performance and the five regional WMH volumes. Additionally, the derived PCR pattern for perceptual speed has a mediating effect on the relationship between age and perceptual speed RA. Even using the PCA approach, we saw no association between vocabulary and the principal components scores.

Although the present study has several strengths, including a large population-based sample, use of effective cognitive measures to study aging and powerful statistical modeling procedures, to deal with the typical limitations of these measurements, we should acknowledge some limitations. Our ability to infer causality is limited by the cross-sectional design. Historically, the study of the aging brain is frequently based on results drawn from cross-sectional studies. (Raz et al., 2005) The conclusions from most studies rely on correlations between age and the specific variable of interest, which deems the possibility to directly report the rate of change associated with age in the same individual differences. We are therefore very cautious in assuming any causality with these results.

In summary, our results stress the importance of studying the entire adult life span to explore the effects of aging on the brain. As WMH are presumed to be MRI correlates of small vessel cerebrovascular disease, our finding supports the claims of emerging importance in the reduction of cardiovascular risk CV factors in adult life. In fact, clinical researchers focused on neurodegenerative disease, recently started assessing midlife interventions to promote healthy aging (Ecay-Torres et al., 2018). Moreover, most studies of WMH in mid adulthood originate from the fields of CV clinical research and, as an expected consequence, cognitive measurement is far from the ideal to study cognitive aging (Pase et al., 2016). On the other hand, studies in older adults have more extensive cognitive assessments but do not explore the modification in WMH patterns across the lifespan. Our work includes adults across a wide age range while assessing cognition with very robust constructs to study aging. To tackle non-linearity problems, we used two different techniques to explore the relationship between age, WMH and RAs. PCA as an exploratory approach and PCR as a predictive model to study the possible cognitive differences dependent on the regional burden of WMH. Lastly, mediation models to further assess the effect of WMH in the relationship between age and each of the four RAs individually, are a powerful approach to dealing with the multiple and intricate relationship between cognitive performance and the effect of aging.

On the whole, because WMH seems to represent a proxy of vascular disease in the brain, their study in the context of aging and outside the scope of dementia is important. By tuning our methods to determine critical regions in the brain where and when these lesions might start affecting cognition, we might contribute to further dissecting the concept of age-related cognitive decline. In fact, if these once considered normal and ubiquitous lesions in older adults could be instead preventable by the same interventions that reduce CV risk factors this could help define what healthy cognitive aging really is (Hörder et al., 2018).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) burden is inversely correlated with performance on two reference abilities (RAs) in perceptual speed and episodic memory;

WMH volume increases in a nonlinear fashion with an inflection point at age 43 years old;

The association between perceptual speed and WMHI burden was the strongest among other Ras.

Parietal WMH regional volume mediates the relationship between age and perceptual speed in simple and multiple mediation models;

These results across the extended adult lifespan help clarify the influence of WMH on cognitive aging.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Predovan, PhD for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [Grant numbers R01 AG026158 and RF1AG038465].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- Belotti F, Deb P, Manning W, Norton E, 2015. twopm: Two-part models. Stata Journal 15, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Booth T, Bastin ME, Penke L, Maniega SM, Murray C, Royle NA, Gow AJ, Corley J, Henderson RD, Hernandez Mdel C, Starr JM, Wardlaw JM, Deary IJ, 2013. Brain white matter tract integrity and cognitive abilities in community-dwelling older people: the Lothian Birth Cohort, 1936.[Erratum appears in Neuropsychology. 2013 Nov;27(6):701]. Neuropsychology 27, 595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Muraskin J, Zimmerman ME, 2009. Structural neuroimaging in Alzheimer’s disease: Do white matter hyperintensities matter? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Provenzano FA, Muraskin J, Manly JJ, Blum S, Apa Z, Stern Y, Brown TR, Luchsinger JA, Mayeux R, 2012. Regional white matter hyperintensity volume, not hippocampal atrophy, predicts incident Alzheimer disease in the community. Archives of Neurology 69, 1621–1627. 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Zahodne LB, Guzman VA, Narkhede A, Meier IB, Griffith EY, Provenzano FA, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Stern Y, Luchsinger JA, Mayeux R, 2015. Reconsidering harbingers of dementia: Progression of parietal lobe white matter hyperintensities predicts Alzheimer’s disease incidence. Neurobiology of Aging 36, 27–32. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge JB, Magee L, Robb AL, 1988. Alternative transformations to handle extreme values of the dependent variable. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83, 123–127. 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke H, Fuld PA, 1974. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology 24, 1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot J, de Leeuw F, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Jolles J, Breteler M, 2001. Cerebral white matter lesions and subjective cognitive dysfunction. The Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology 56, 1539–1545. 10.1212/WNL.56.11.1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot JC, De Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, Van Gijn J, Hofman A, Jolles J, Breteler MMB, 2002. Periventricular cerebral white matter lesions predict rate of cognitive decline. Annals of Neurology 52, 335–341. 10.1002/ana.10294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw FE, De Groot JC, Achten E, et al. , 2001. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. Journal of neurology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, Hald J, Tullberg M, Au R, Beiser A, D’Agostino R, Wolf PA, 2005. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: Establishing what is normal. Neurobiology of Aging 26, 491–510. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ, 2006. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage 31, 968–980. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draganski B, Lutti A, Kherif F, 2013. Impact of brain aging and neurodegeneration on cognition. Current Opinion in Neurology 26, 640–645. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecay-Torres M, Estanga A, Tainta M, Izagirre A, Garcia-Sebastian M, Villanua J, Clerigue M, Iriondo A, Urreta I, Arrospide A, Díaz-Mardomingo C, Kivipelto M, Martinez-Lage P, 2018. Increased CAIDE dementia risk, cognition, CSF biomarkers, and vascular burden in healthy adults. Neurology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, Van Der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM, 2002. Whole brain segmentation: Automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 33, 341–355. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni GB, Galluzzi S, Pantoni L, Filippi M, 2007. The effect of white matter lesions on cognition in the elderly—small but detectable. Nature Clinical Practice Neurology 3, 620–627. 10.1038/ncpneuro0638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ, 1978. Stroop Color and Word Test: A manual for clinical and experimental uses. Chicago: Stoelting; 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1002 [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M, 1991. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 13, 933–949. 10.1080/01688639108405109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habeck C, Foster NL, Perneczky R, Kurz A, Alexopoulos P, Koeppe RA, Drzezga A, Stern Y, 2008. Multivariate and univariate neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage 40, 1503–1515. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habeck C, Gazes Y, Razlighi Q, Steffener J, Brickman A, Barulli D, Salthouse T, Stern Y, 2016. The Reference Ability Neural Network Study: Life-time stability of reference-ability neural networks derived from task maps of young adults. NeuroImage 125, 693–704. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörder H, Johansson L, Guo X, Grimby G, Kern S, Östling S, Skoog I, 2018. Midlife cardiovascular fitness and dementia. Neurology 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005290 . 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005290https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005290. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Yang AC, Chou KH, Liu ME, Fang SC, Chen CC, Tsai SJ, Lin CP, 2018. Nonlinear pattern of the emergence of white matter hyperintensity in healthy Han Chinese: an adult lifespan study. Neurobiology of Aging 67, 99–107. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, 2013. The Pathobiology of Vascular Dementia. Neuron 80, 844–866. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Habeck C, Razlighi Q, Salthouse T, Stern Y, 2016. Selective association between cortical thickness and reference abilities in normal aging. NeuroImage 142, 293–300. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemer ER, Greve DN, Fischl B, Augustinack JC, Salat DH, 2017a. Differential Regional Distribution of Juxtacortical White Matter Signal Abnormalities in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 57, 293–303. 10.3233/JAD-161057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemer ER, Greve DN, Fischl BR, Augustinack JC, Salat DH, 2017b. Regional staging of white matter signal abnormalities in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage: Clinical 14, 156–165. 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth WT, Manolio TA, Arnold A, Burke GL, Bryan N, Jungreis CA, Enright PL, O’Leary D, Fried L, 1996. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people: The cardiovascular health study. Stroke 27, 1274–1282. 10.1161/01.STR.27.8.1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S, 1988. Dementia Rating Scale Resources Inc Odessa, F.L: Psychological Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- McGee VE, Carleton WT, 1970. Piecewise regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association 65, 1109–1124. 10.1080/01621459.1970.10481147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- S. P, G. C, A. M, B. D, F. A, B. A, H. M, I. R, S. V, Z. C, H. B, 2011. An automated tool for detection of FLAIR-hyperintense white-matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pase MP, Himali JJ, Mitchell GF, Beiser A, Maillard P, Tsao C, Larson MG, Decarli C, Vasan RS, Seshadri S, 2016. Association of Aortic Stiffness with Cognition and Brain Aging in Young and Middle-Aged Adults: The Framingham Third Generation Cohort Study. Hypertension 67, 513–519. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepho HP, Ogutu JO, 2003. Inference for the break point in segmented regression with application to longitudinal data. Biometrical Journal 45, 591–601. 10.1002/bimj.200390035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prins ND, Van Dijk EJ, Den Heijer T, Vermeer SE, Jolles J, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Breteler MMB, 2005. Cerebral small-vessel disease and decline in information processing speed, executive function and memory. Brain 128, 2034–2041. 10.1093/brain/awh553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, Dahle C, Gerstorf D, Acker JD, 2005. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cerebral Cortex 15, 1676–1689. 10.1093/cercor/bhi044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R, 1958. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and motor skills 8, 271–276. 10.2466/PMS.8.7.271-276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debette S, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Au R, Himali JJ, Palumbo C, W. PA and D. C, 2011. Midlife vascular risk factor exposure accelerates structural brain aging. Neurology 77, 461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Lee SY, van der Kouwe AJ, Greve DN, Fischl B, Rosas HD, 2009. Age-associated alterations in cortical gray and white matter signal intensity and gray to white matter contrast. NeuroImage 48, 21–28. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA, 2009. Decomposing age correlations on neuropsychological and cognitive variables. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 15, 650–661. 10.1017/S1355617709990385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA, 2005. Relations Between Cognitive Abilities and Measures of Executive Functioning. Neuropsychology July 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA, Habeck C, Razlighi Q, Barulli D, Gazes Y, Stern Y, 2015. Breadth and age-dependency of relations between cortical thickness and cognition. Neurobiology of Aging 36, 3020–3028. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Jeng J, Fischl B, Blacker D, 2011. Correlations between MRI white matter lesion location and executive function and episodic memory. Neurology 76, 1492–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, 2012. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, Habeck C, Steffener J, Barulli D, Gazes Y, Razlighi Q, Shaked D, Salthouse T, 2014. The Reference Ability Neural Network Study: Motivation, design, and initial feasibility analyses. NeuroImage 103, 139–151. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Vermeer SE, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MMB, 2002. Frequency of white matter lesions and silent lacunar infarcts. Journal of neural transmission. Supplementum 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, 2001. The Wechsler test of adult reading (WTAR), Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D, 1997. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-3R), San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegman AF, Meier IB, Provenzano FA, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Stern Y, Luchsinger JA, Brickman AM, 2013. Regional white matter hyperintensity volume and cognition predict death in a multiethnic community cohort of older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 10.1111/jgs.12568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D, Ortega M, Martinez O, Mungas DM, Reed BR, DeCarli CS, 2006. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology 67, 2192–2198. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249119.95747.1f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon request.