Abstract

Background

Numerous international studies have examined cross-sectional correlates of food insecurity (FI) among post-secondary students; a study is needed to synthesize the findings of this work to support vulnerable students.

Objective

To systematically review peer-reviewed and gray literature to assess the prevalence of FI on post-secondary institutions, as well as factors related to FI among students and suggested/practiced solutions.

Design

Systematic literature review. MEDLINE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO databases were searched for peer-reviewed literature for FI research; a Google search was conducted to obtain gray literature on FI among post-secondary students.

Participants/Setting

Undergraduate and graduate students at post-secondary institutions of higher education.

Main outcome measures

Measures included 1) prevalence of FI; 2) socio-demographic, health, and academic factors related to FI; 3) solutions to address FI on post-secondary institutions.

Results

Seventeen peer-reviewed studies and 41 sources of gray literature were identified (out of 11,476 titles). All studies were cross-sectional. Rates of FI were high among students, with average rates across the gray and peer-reviewed literature of 35% and 42%, respectively. FI was consistently associated with financial independence, poor health and adverse academic outcomes. Suggested solutions to address food security among post-secondary institutions addressed all areas of the socio-ecological model, but the solutions most practiced included those in the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional levels.

Conclusions

FI is a major public health problem among post-secondary students. Studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of FI among this vulnerable population. More research is needed on the effectiveness of FI interventions.

Keywords: food insecurity, emerging adults, college campuses

While the traditional concept of the post-secondary student tends to include younger individuals coming from more affluent families, the modern post-secondary student reflects a paradigm shift in student demographics.1,2 Students of low socio-economic status who may have once dismissed the possibility of degree attainment are now seizing opportunities to pursue post-secondary education.3,4 Older men and women who may have abandoned college due to past financial hardship, or to raise a family, now have an opportunity to complete degree programs.5–7 Single parents who may not have previously considered pursuing an education are realizing the advantage of obtaining a degree,8 and are seeking to enroll in post-secondary institutions. These students, who vary so greatly in age, background, and socio-economic status, are all working towards the same goal: to gain crucial skills and position themselves in a place of greater prosperity and well-being. Yet adequate nutritious food, a basic need for human well-being, may not consistently be available to these students. As such, one emerging area of concern among college students and post-secondary institutions is food insecurity (FI),9 or the lack of consistent access to safe and healthy foods. Among children and adolescents, FI has been shown to be related to higher stress and anxiety,10 poorer academic outcomes,10 and poorer nutritional status and health outcomes.11,12 Among adults, FI is linked to lower work productivity13,14 and chronic disease.15,16 The long-term effects of FI among college students has yet to be explored.

Articles in the popular press about FI on college campuses have become more frequent, having been featured by outlets from the Chronicle of Higher Education17 to the New York Times.18,19 An active, national association for food pantries on college campuses, College and University Food Bank Alliance, now has over 375 members.20 A clearer understanding of the scope of the problem of FI on college campuses is needed, as well as a better understanding of a comprehensive range of strategies that are being utilized to help college students facing FI. Thus, the aim of this study was to systematically review both the peer-reviewed and “gray” literature to obtain a holistic picture of what is known about FI and what is being done about FI on post-secondary institutions. By synthesizing the existing literature base on FI at post-secondary institutions, we can collectively design more effective prevention interventions for this vulnerable population.

Methods

To explore FI among post-secondary students in-depth, we conducted a systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), there are four thresholds of food security:21 food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security. Low food security and very low food security are the terms to describe FI. The notion that college students are increasingly FI has gained growing attention in recent years from governmental entities, educational entities, and faith-based and philanthropic organizations, among others. Considering the rate at which this issue is gaining popular attention, both peer-reviewed literature and gray literature were explored to present a more inclusive, broad picture of the issue at hand. Gray literature included published (non-peer reviewed) reports, student theses, conference presentations, newsletters, and data published on websites. Peer-reviewed literature was identified by searching MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science, and PsycINFO electronic databases. All text fields were searched (title, abstract, full-text), and papers published in English between January 2001 and August 2016 were eligible for consideration. To provide a more accurate representation of the subject matter, materials from all geographical regions were accepted. Search terms comprised of hunger, food insecurity, food security, food hardship, food secure in combination WITH/AND tertiary education, university, college, college campus, community college, college students. Gray literature was identified via Google search using the above search terms with the removal of WITH/AND in the search text. Lab notes, excel sheets, and citation managers were used in conjunction to manage the data selection and extraction records.

Selection Criteria

Two reviewers (KA, MB) independently screened peer-reviewed papers retrieved from electronic databases for eligibility. Studies were only included if they had assessed FI among post-secondary student populations (including vocational, undergraduate, graduate, and professional students). Animal studies, metabolism studies, and papers exploring satiety, eating motivation and behavior, and nutrition status (that did not measure FI and/or study a post-secondary student population) were excluded. Titles, abstracts, and full-text (when necessary) were reviewed to assess eligibility of studies based on these criteria.

To identify gray literature, Google search results were screened for any relationship to FI among college students for the first 250 results, or until two pages (50 possibilities) without any relevant results, before the next set of search terms were input. All search term combinations, page titles, and URLs for eligible results were documented for further assessment. After all search combinations were documented, URLs were then re-assessed to ensure that eligible sources contained new data not previously identified in the peer-reviewed literature search. All gray literature sources were screened, identified and documented between May 23, 2016 and July 20, 2016.

Data Extraction

MB, ML, and DCP reviewed the peer-reviewed literature and extracted the following data: data collection frame, study design and analytical approach, setting, sample demographics, FI measures, outcome measure(s), prevalence of FI and results. We extracted all results and categorized the results into demographic (e.g., race/ethnicity, age), health (e.g., eating behaviors, mental health, weight status), and academic (e.g., grade point average, retention) outcomes. MB and KA reviewed the gray literature for source type (report, student thesis, abstract, website, press article), year data were collected, sample size, prevalence of FI and factors associated with student FI. Themes for suggested solutions and interventions in practice were categorized across both the peer-reviewed literature and gray literature. We calculated unweighted mean prevalences of FI, low and very low food security in the respective types of studies. If more than one measure was used to assess food insecurity, the more comprehensive measure was used to calculate the average.

Results

Overview of included studies

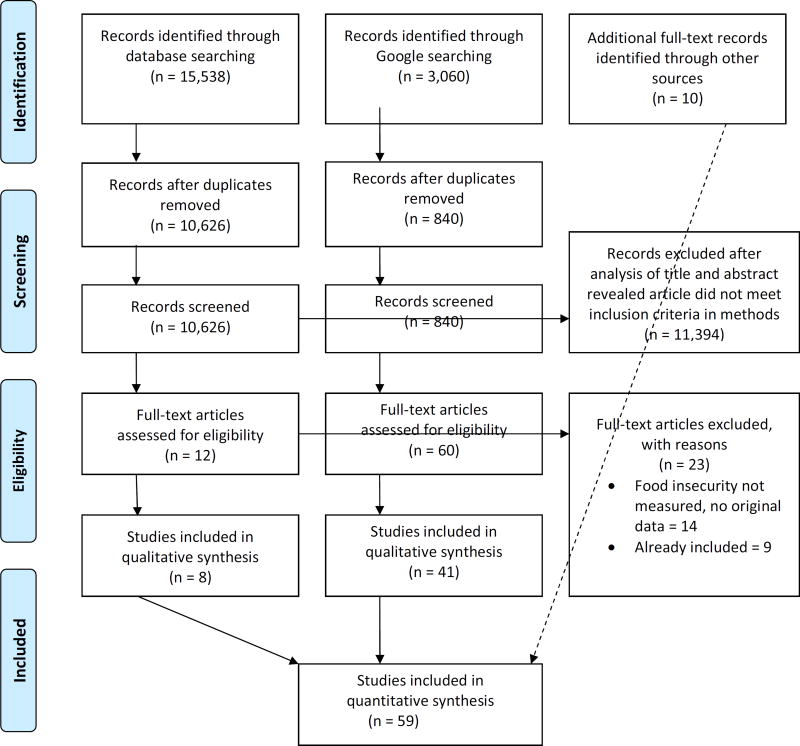

A total of 18,608 records were identified through peer-reviewed electronic databases (n=15,538), Google searches (n=3,060), and other peer-reviewed sources (n=10) (see Figure 1). After removing duplicates, 11,476 titles were screened (n=10,636 peer-reviewed; n=840 gray literature). Of these articles, 11,394 were excluded after title and abstract analysis revealed they did not meet inclusion criteria outlined in the methods. The remaining 82 full-text articles (n=22 peer-reviewed; n=60 gray literature) were then screened. Fourteen peer-reviewed papers were excluded for not assessing prevalence of FI or providing new data, and nine gray literature sources were already included among the peer-reviewed literature resulting in a total of 23 excluded full-text articles. The remaining 18 peer-reviewed papers and 41 gray literature sources were found to meet all inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Two peer-reviewed papers used an identical sample,22,23 so those are considered here as one study. In the gray literature, three gray literature items came from the University of Alaska, Anchorage,24–26 and two studies came from Michigan Technical University;27,28 these were combined for two items from each respective institution. Gray literature was further divided to explore current (n=17) and proposed solutions (n=24) addressing student FI. In total, this systematic review examined the findings from 59 peer-reviewed and gray literature papers assessing the prevalence of and factors contributing to FI among higher education students, as well as provides an in-depth exploration of current and proposed interventions and solutions. In general, many similarities were observed among the peer-reviewed and gray literature. Similarly, major differences were not observed between US-based and international studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of peer-reviewed and gray literature on food insecurity in higher education settings

Description of institutions

Of the peer-reviewed studies, nine were based in the US,29–37 and nine were international (Table 1): three were based in South Africa,38–40 three were based in Australia,41–43 two were based in Canada22,23 (these were counted as one) and one was based in Malaysia44 (Table 2). Most peer-reviewed studies were conducted at public, 4-year institutions in urban settings. A little less than a quarter (22%) of peer-reviewed studies were conducted at minority-serving institutions (Table 1)

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of post-secondary institutions included in this systematic review by study1

| Peer-reviewed n=17 |

Gray literature n=41 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Location %(n) | ||

| US-based | 52.9% (9) | 90.2% (37) |

| International | 47.1% (8) | 9.8% (4) |

| Type %(n) | ||

| Vocational school | -- | -- |

| Community college | 5.9% (1) | 7.3% (3) |

| 4-year institution + PhD | 76.5% (13) | 85.4% (35) |

| Mixed | -- | 7.3% (3) |

| Unknown | 17.6% (3) | -- |

| Demographic %(n) | ||

| Hispanic Serving Institution | 17.6% (3) | 19.5% (8) |

| Historically Black College and University | 5.9% (1) | -- |

| Other | 35.3% (6) | 68.3% (28) |

| N/A (e.g., international) | 41.2% (7) | 9.8% (4) |

| Unknown | -- | 2.4% (1) |

| Funding status %(n) | ||

| Public | 82.4% (14) | 90.2% (37) |

| For-profit | -- | 9.8% (4) |

| Unknown | 17.6% (3) | -- |

| Locale %(n) | ||

| Urban | 76.4% (13) | 63.4% (26) |

| Rural | 5.9% (1) | 29.3% (12) |

| Mixed | 11.8% (2) | 7.3% (3) |

| Unknown | 5.9% (1) | -- |

Some studies included multiple institutions

Table 1.

Summary of peer-reviewed studies on food insecurity (FI) among post-secondary students (years 2000–2016)

| First author, publication date |

Data collection time frame |

Setting | Sample demographics | Study design Analytical approach |

FI measures | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of FI | Socio-demographics and related factors |

Physical and mental health |

Academic | ||||||

| Chaparro, 2009 | Fall 2006 | University of Hawai’i at Manoa, US |

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

|

NA2 | NA2 |

| Hughes, 2011 | NA2 | Gold Coast Campus, Australia |

|

|

18-item USDA Food Security Module |

|

|

|

NA2 |

| Micevski, 2013 | 2012 | Deakin University, Australia |

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

|

NA2 | NA2 |

| Lin, 2013 | Spring 2011 | Historically Black College or University in Texas, US |

|

|

“In the past month, have you experienced problems with food insecurity?” | NA2 | NA2 |

|

NA2 |

| Munro, 2013 | 2007–2010 | University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa |

|

|

University Students Food Insecurity Questionnaire, developed by the authors |

|

|

|

|

| Kassier, 2013 | Spring 2012 | University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa |

|

|

Household Food Insecurity Access Scale |

|

NA2 |

|

|

| Patton-Lopez, 2014 | Spring 2011 | Rural university in Oregon, US |

|

|

USDA 6-Item Short Form Food Security Survey Module |

|

|

|

|

| Gallegos, 2014 | Fall 2009 | Brisbane, Australia |

|

|

18-item USDA Food Security Module |

|

|

|

|

| Hanna, 2014 | NA | California college campuses |

|

|

18-item USDA Food Security Module |

|

|

NA2 |

|

| Gaines, 2014 | Fall 2011 |

|

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

|

|

NA2 |

| Van den Berg, 2015 | 2013 | University of the Free State, South Africa |

|

|

|

|

Race (−0.50; SE=0.14; p=0.003), having enough money for food (1.05; SE=0.14; p<0.001), asking others for money for food (1.20; SE=0.20; p<0.001), selling positions to obtain food (1.45; SE=0.4627; p=0.002), and borrowing money from parents for food (−0.58; SE=0.27; p=0.032) were associated with FI. | NA2 | NA2 |

| Nur Atiqah, 2015 | NA | University Teknologi MARA Puncak Alam, Malaysia |

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

NA2 |

|

NA2 |

| Maroto, 2015 | Fall 2012 | Two community colleges in Maryland, U.S. (one college in an extremely affluent suburban area and one in a lower-income urban area |

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

|

NA2 |

|

| Silva, 2015 | Fall 2014–Spring 2015 | UMass Boston, US |

|

|

Worry about having enough money for food, skipping meals due to a lack of money to buy food, inability to eat nutritious meal due to monetary struggles, did not eat for more than 1–2 days |

|

NA2 | NA2 |

|

| Farahbakhsh, 2016a, 2016b | 2013–2014 | University of Alberta, Canada |

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

|

|

|

| Bruening, 2016 | 2014–2015 | Arizona State University, US |

|

|

Two-item screener |

|

|

|

NA2 |

| Morris, 2016 | Spring 2013 | 4 public universities in Illinois, US (Eastern Illinois University, Northern Illinois University, Southern Illinois University, and Western Illinois University) |

|

|

10-item Adult Food Security Module |

|

|

NA2 |

|

Cross sectional

Not available

The terminology in the reviewed manuscript used food insecurity with and without hunger. We updated to low and very low food insecurity, respectively, in order to have consistency.

Rates of food insecurity vary based on using a single item versus multiple item scale

Among the sources of gray literature, all but four were based in the US: two were based in Canada,45,46 one was based in New Zealand,47 and one was based in Mexico48 (Table 3). The majority of the gray literature was derived from public, 4-year US-based institutions also in urban settings.

Table 3.

Gray literature reporting prevalence and factors related to food insecurity (FI) on post-secondary campuses, Years 2000–2015

| Institution, Country |

First author, date published |

Source | Year data collected |

Sample size | FI prevalence | Factors associated with student FI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographics | Physical and mental health | Academic | ||||||

| City University of New York, US | 2011 | Report | 2010 |

|

39.2% FI |

|

|

NA |

| San Jose State University, US | 2014 | Report | NA |

|

39.0% FI |

|

NA |

|

| Autonomous University of Queretaro, Mexico | Anaya-Loyola, 2014 | Abstract | NA | n=66 | 50.5% FI | NA |

|

NA |

| University of Alaska Anchorage, US | Lindsley | Student poster | Fall 2013 | n=63 | 55% FI | NA | NA | NA |

| Nelson | Student thesis | 2015 | NA | 12.3–31% FI1 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Wintz | Report | NA | n=454 | 31% FI |

|

|

NA | |

| 10 US Community Colleges | Wisconsin HOPE Lab, 2015 | Report | 2015 |

|

|

|

|

NA |

| Humboldt State University, California, US | Maguire, 2015 | Report | NA | n=1554 |

|

|

NA | NA |

| University of Canterbury, New Zealand | Walsh, 2014 | Student thesis | NA | n=305 | NA | NA |

|

|

| University of Lethbridge, Canada | Nugent, 2011 | Student thesis | Fall 2010–Spring 2011 |

|

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pacific University, US | Moore, 2014 | Student thesis | NA |

|

|

NA |

|

NA |

| Maryland community colleges, US | Maroto, 2013 | Student thesis | Fall 2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

| University of Arkansas, US | MacDonald, 2016 | Student thesis | 2016 |

|

40% FI |

|

NA |

|

| University of Central Florida, US | Loftin, 2013 | Student thesis | 2012 |

|

NA |

|

NA | NA |

| Bowling Green State University, US | Koller, 2014 | Student thesis | Spring 2014 |

|

|

|

NA | NA |

| Kent State, US | Gorman, 2014 | Student thesis | Spring 2014 |

|

|

|

NA | NA |

| California State University, US | Espinoza, 2013 | Student thesis | Fall 2012 |

|

|

|

|

NA |

| Humboldt State University, US | Chappelle, 201S | Student thesis | Fall 2014 |

|

|

NA |

|

NA |

| University of California San Francisco, US | Office of Intuitional Research | Report | Spring 2015 | n=921 | 13% FI | NA |

|

|

| Michigan Technical University, US | Gorman | Report | NA | n=1011 | 26% FI | NA | NA | NA |

|

Report | Spring 2015 | n=1011 | 26% FI |

|

NA | NA | |

| University of New Hampshire, US | Davidson, 2015 | Abstract | Fall 2014 | n=418 | 12.4% FI |

|

NA | NA |

| California State Polytechnic University, US | Burns-Whitmore, 2012 | Abstract | NA | n=131 | 46% FI |

|

NA | NA |

| Fresno State, US | NA | Press article | NA | n=674 | 30.7% | NA | NA | NA |

| Gavilan College, US | Institutional Research, 2013 | Report | Fall 2013 | n=155 | 38.8–45.2%1 | NA | NA | NA |

| University of Northern British Columbia, Canada | Booth, 2016 | Report | Fall 2015 |

|

39% |

|

NA |

|

| Wisconsin Public Colleges, US | Broton, 2014 | Report | Fall 2008 | n=1413 | Approximately 20% | NA | NA | NA |

NA=Not available

CalFresh=The name for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in California

Ranges indicate multiple measures of FI

Study samples

Across the peer-reviewed and gray literature, the average sample was 442 participants. The smallest study was a qualitative study from the gray literature with 15 participants, and the largest study was also from the gray literature with a sample of 4972, including participants from several post-secondary institutions. With few exceptions, more females tended to participate in FI studies as compared to males (Tables 2 and 3). The age range of studies varied greatly, as one focused on university freshmen, two others excluded freshmen, and three studies included graduate students.

Study measures

All of the peer-reviewed studies utilized a cross-sectional design. In assessing prevalence of FI, the majority of the peer-reviewed studies used the 10-item USDA food security questionnaire for adults (n=9), three studies used the 18-item USDA Food Security Module,32,41,43 two studies used validated food security screeners,31,36 and the remaining studies used newly developed FI assessment measures.30,35,38 The gray literature rarely reported measurement tools.

Study rigor

Most of the peer-reviewed studies used basic descriptive or bivariate analyses. Only half of the studies assessed results using multivariate regressions to adjust for potentially confounding variables.30,31,33,34,36,40,42,43 In addition, the majority of studies used convenience samples. Two peer-reviewed studies invited a random sample of students enrolled in specific academic courses to participate in the study,29,33 but the participation among faculty leading these courses was low. In fact, response rates were relatively low across most studies that reported response rates.

Prevalence of FI

The peer-reviewed literature tended to report more detailed results for the prevalence of FI, with an average rate of FI as 42.0% (range: 12.5–84%). For nine peer-reviewed studies from the U.S. only, the average rate of FI was 32.9% (range: 14.1–58.8%). Within the gray literature, the average FI prevalence was 35.6% (range: 12.4–56%). Amongst the peer-reviewed studies that differentiated between low and very low food security, the average prevalence was 18.1% (range: 8.9–26%) and 22.4% (range: 5.1–59%), respectively.

Socio-demographic, health, and academic factors related to FI

When examining factors related to FI, themes were identified across socio-demographic, health, and academic outcomes. Almost all studies examined relationships between FI and socio-demographics. Students of color, younger students, students with children, and students who were financially independent were more likely to report FI. The most common demographic factors related to FI were: independence among students (including living, financial, and food independence from parents) assessed in six peer-reviewed studies29,33,34,40–42 and eight gray literature findings;26,27,45,49–53 receiving loans and governmental support was assessed by four peer-reviewed studies33,37,38,42 and two gray literature findings,45,54 respectively. Over half of the peer-reviewed studies (n=9) and 24% (n=10) of the gray literature findings reported health related outcomes.

FI was associated with lower overall self-reported health among four out of four peer-reviewed studies that examined this issue,23,30,31,41 and poorer eating behaviors (e.g., lower fruit and vegetable consumption) were reported in three out of three peer-reviewed studies that examined this issue.23,36,43 A total of eight peer-reviewed studies and six gray literature findings examined academic outcomes related to FI.. Among those studies, five studies (three peer-reviewed and two gray literature) reported that lower GPA was associated with FI,31,34,37,55,56 and eight studies (three peer-reviewed and five gray literature) reported adverse academic outcomes ranging from having difficulty concentrating in class to higher prevalence of withdrawing from class or the institution.

Suggested and practiced solutions to addressing FI at post-secondary institutions

No efficacy or effectiveness studies were identified that addressed FI on post-secondary campuses in either peer-reviewed or gray literature (Table 4). However, in the discussion sections of many published papers included in this review, authors suggested solutions for addressing FI among post-secondary students across each level of the socio-ecological model. The most commonly suggested interventions included individual financial coaching (suggested in six peer-reviewed studies and five gray literature works), implementation of institutional-level interventions including on-campus food pantries (suggested by seven peer-reviewed and two gray literature studies), and policy/systems level changes to increase financial aid/create a basic living stipend for students (suggested by nine peer-reviewed studies and two gray literature works) and allowing students to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.

Table 4.

Themes of suggested solutions and solutions in practice to address post-secondary food insecurity by socio-ecological construct1

| Socio-ecological construct | Common examples | Peer-reviewed literature, suggested (n=18) |

Gray lit, suggested (n=24) |

Gray literature, practiced (n=17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal |

|

33.3% (6) | 20.8% (5) | 35.3% (6) |

|

5.5% (1) | -- | 23.5% (4) | |

| Interpersonal |

|

-- | -- | 5.9 % (1) |

|

-- | -- | 23.5% (4) | |

|

-- | -- | 11.8% (2) | |

| Organizational/institutional |

|

38.9% (7) | 8.3% (2) | 41.2% (7) |

|

5.5% (1) | -- | ||

|

27.8% (5) | 12.5% (3) | -- | |

| Community |

|

22.2% (4) | -- | 11.8% (2) |

|

5.5% (1) | 16.7% (4) | ||

|

22.2% (4) | 16.7% (4) | 5.9 % (1) | |

| Policy/systems |

|

27.8% (5) | 20.8% (5) | 11.8% (2) |

|

-- | 8.3% (2) | 5.9 % (1) | |

|

50.0% (9) | 8.3% (2) | -- |

To date, solutions were as suggested by authors.

Further, a portion of the gray literature reported on ongoing interventions on campuses, the most common being campus food pantries (n=7) and financial coaching (n=6). The gray literature that described solutions was the only literature that addressed interpersonal interventions. For example, two projects described an app for mobile phones in which students can share excess meal plans points with peers in need.

Discussion

FI is a complex problem and is understudied among post-secondary students. This study sought to systematically review peer-reviewed and gray literature to examine the prevalence of FI on post-secondary institutions, factors related to FI among students, and describe solutions to address FI for students in need. Over 11,000 peer-reviewed manuscripts and sources of gray literature were screened, and ultimately a total of 59 works were included in the review. Just nine of those studies included peer-reviewed papers from the US, which is a limited amount of research. Across the globe, students attending post-secondary institutions experience high rates of FI. FI appears to be alarmingly high at post-secondary institutions, and the limited evidence available to date suggests that it is experienced by an average of approximately one-third to one-half of students across the institutions assessed. More research is needed to effectively support the students in need.

Compared to FI prevalence data among the general US population, the data from the US-based studies suggest almost a two-fold higher rate of FI among post-secondary students.57 Higher rates compared to national levels were also observed in Canada, Australia,58 and New Zealand.59 The studies conducted in South Africa showed similar or lower rates than their respective countries’ national averages.60 Given the high rates, more interventions are needed to assist students struggling with access to food.

In studies among children and adults, FI has been associated with poorer nutrition and health outcomes,11,61,62 higher stress and depression,62,63 and adverse learning,10 academic outcomes,10,64 and/or productivity.62 The results from the reviewed studies indicated that post-secondary students facing FI report similar negative outcomes; findings were generally consistent across the peer-reviewed and gray literature, despite using different metrics. Attention to this public health problem has grown dramatically, particularly given all of the gray literature published in recent years. It appears that the most common approach to addressing on-campus FI is focused on “quick wins” at the intrapersonal level (e.g., educational programming) and interpersonal level (food donation among peers, faculty, and staff), and institutional level (food pantries). Interestingly, no identified studies on FI in post-secondary settings described the role of families as a means of solutions in addressing FI, which may be because families have limited capacity to support struggling students. Moving forward, it would be helpful for investigators to use a consistent set of metrics for outcomes for any FI evaluation study. Multiple metrics for health and academic outcomes may also be needed. For example, in examining academic impacts of FI, ideally objective GPA would be included, but also items such as number of credits, dropping classes, and time to graduation would be assessed.

Overall, there was a lack of variation among the types of colleges and student populations assessed in the peer-reviewed FI studies: most-peer reviewed studies were urban-based, public, 4-year institutions. In order to have a better understanding of the severity of FI among post-secondary students, studies are needed on the prevalence, determinants, and consequences of food insecurity in rural and small-town post-secondary settings, Hispanic-serving institutions, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, community and technical colleges, and for-profit universities. There needs to be more studies that include graduate students, professional students, male students, students from underserved backgrounds, and non-traditional students. Given that most studies used convenience samples and simple descriptive analyses, future research is needed using more rigorous study designs and analyses (i.e., larger, representative samples) focusing on both predictors and consequences of FI. As more studies are published on FI in college students, there may be some hesitation among some university administrators to come to terms with the depth and breadth of FI among students. Qualitative and quantitative research is needed on how students perceive, live, and survive with FI. Ultimately, research on how FI affects student retention, academic success, and costs to the university is critical to having systemic buy-in to address the problem.

Furthermore, there is a dearth of studies examining longitudinal effects of FI; there are no such studies in post-secondary settings. As such, it is unclear as to why the prevalence of FI on post-secondary campuses is so high. Are these students experiencing FI prior to arriving on campus? Do they struggle in managing their resources once they arrive? Do younger students report higher rates of FI as a result of transitioning to having more responsibilities? How does FI impact student retention in representative samples? Does the current literature under- or over-represent FI as a problem among students due to reliance, to a large extent, on convenience sampling? How does struggling with FI while a student impact one’s career? Do problems of FI improve or resolve after graduation? Much more research is needed to better understand the systemic root causes of FI and how prevalence of FI changes throughout the post-secondary years and beyond.

Many of the interventions identified in the gray literature to address FI on campus were led by students themselves. However, because no studies have been published from ongoing interventions, the efficacy of these interventions at reducing rates of FI is unclear. For example, three studies were not included in this review because they did not assess the prevalence of FI or examine the national quality of student food pantries, the cost of food pantries, and the acceptability of food pantries.65,66 However, to our knowledge, not a single study has examined the effectiveness of food pantries at decreasing FI on post-secondary institutions. While it appears that these interventions are being implemented on a variety of university settings (urban and rural, public and private, 4-year institutions and community colleges), more research is needed if these interventions can realistically be effective across an array of university settings and across the socio-ecological model.

The College and University Food Bank Alliance is tracking and supporting the development of food pantries on campus.20 Only a few studies have examined the effectiveness of food pantries among other populations.67,68 Based on this review, there are differences in what has been discussed and suggested in the peer-reviewed literature and to what is practiced in the field. For example, many authors of peer-reviewed studies suggested systems and policies changes for addressing FI (e.g., additional financial support systems such as improved SNAP eligibility for students). Eligibility for college students into the SNAP program can be a challenge; according to USDA, US citizens enrolled at least half time in a post-secondary institution are not eligible for SNAP.69 SNAP benefits cannot be used for students who receive more than half of their meals from a meal plan, excluding most students living in residence halls (a notable population in which FI has been reported,36 though the contributing factors for FI in this group are largely unknown). However, if students work at least 20 hours per week, participate in a financed work-study program, have dependents under the age of 6 (or do not have adequate childcare that inhibits their ability to work 20 or more hours), and/or receive benefits under a Title IV-A program, they would be SNAP eligible.69

Notably, only one piece of gray literature reported policy-level changes to address FI. In 2015, the state of California passed a bill that is aimed at improving FI among post-secondary students.70 In this bill, activities include improving coordination between food banks and college food pantries and increasing access to funds supporting CalFresh (SNAP) outreach to students. In order to address the systemic issue of FI, national systems solutions may be needed and tested. Again, more research is needed to understand how to best support post-secondary students with FI. If FI can be addressed on campuses, the lessons learned can be applied to support other communities facing FI.

Study strengths and limitations

Given the variability in the measures used, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis through this review. In addition studies used a variety of tools to measure FI; however, most studies used validated tools of FI. Many of the reviewed studies used descriptive study designs and analyses were often limited to bi-variate associations. Unmeasured confounding may explain some of the findings reported by authors. Most studies used a convenience sample of post-secondary students; it is possible that participation in studies may have been more enticing to food insecure risk students, biasing the samples. In conclusion, FI is a major problem among students at post-secondary institutions. More research is needed among representative samples to understand which students are at greatest risk of FI, and to understand how FI changes over time. Studies with rigorously designed interventions are needed so that resources can be targeted to the interventions most effective at improving rates of FI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: the authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Meg Bruening, School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, Arizona State University, 550 N 5th Street, Phoenix, AZ 85004; 602.827.2266; meg.bruening@asu.edu.

Katy Argo, Undergraduate nutrition student, School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, Arizona State University, 550 N 5th Street, Phoenix, AZ 85004; kary.argo@asu.edu.

Devon Payne-Sturges, Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health, School of Public Health, University of Maryland, College Park; (301) 405-2025; dps1@umd.edu.

Melissa Laska, University of Minnesota, 1300 S. 2nd Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis MN 55454; 612-624-8832; mnlaska@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Hurtado S, Carter DF, Spuler A. Latino student transition to college: Assessing difficulties and factors in successful college adjustment. Res High Educ. 1996;37(2):135–157. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macilwain C. US higher education: The Arizona experiment. Nature. 2007;446(7139):968–970. doi: 10.1038/446968a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin M, Denson N, Kilpatrick S, et al. “I Am Working-Class” subjective self-definition as a missing measure of social class and socioeconomic status in higher education research. [published online ahead of print March 19 2014] Educ Res. 2014;43(4):196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devlin M. Bridging socio-cultural incongruity: Conceptualising the success of students from low socio-economic status backgrounds in Australian higher education. Stud High Educ. 2013;38(6):939–949. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahu ER, Stephens C, Leach L, Zepke N. The engagement of mature distance students. Int J FYHE. 2013;32(5):791–804. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wladis C, Hachey AC, Conway KM. The representation of minority, female, and non-traditional STEM majors in the online environment at community colleges a nationally representative study. [published online ahead of print November 24 2014] Community Coll Rev. 2015;43(1):89–114. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor L. Can I do both? Be employed and graduate? Adult non-traditional learners who combine employment and higher education enrollment-A look at persistence and best practices to overcoming barriers to improve success and retention; Adult Education Research Conference; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson B, Froehner M, Gault B. College students with children are common and face many challenges in completing higher education. Briefing Paper# C404. Institute for Women's Policy Research. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubick J, Mathews B, Cady C. [Accessed October 24, 2016];Hunger on campus, the challenge of food insecurity for college students. CUFBA Web site. Published October 2016. Available at: http://www.cufba.org/report-hunger-on-campus/

- 10.Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food insecurity affects school children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J Nutr. 2005;135(12):2831–2839. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.12.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilton M, Chyatte M, Breaux J. The negative effects of poverty & food insecurity on child development. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126(4):262–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):65–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borre K, Ertle L, Graff M. Working to eat: vulnerability, food insecurity, and obesity among migrant and seasonal farmworker families. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(4):443–462. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, et al. “A lot of sacrifices:” Work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(10):2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(2):203–212. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolowich S. [Accessed October 24, 2016];How many college students are going hungry? The Chronicle of Higher Education Web site. Published 2015. Available at: http://www.chronicle.com/article/How-Many-College-Students-Are/234033?cid=trend_right.

- 18.Saul S. [Accessed October 24, 2016];Food pantries address a growing hunger problem at colleges. The New York Times Web site. Published 2016. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/23/education/food-pantries-address-a-growing-hunger-problem-at-colleges.html?_r=1.

- 19.Pappano L. [Accessed October 24, 2016];Leftover meal plan swipes: No waste here. The New York Times Web site. Published 2016. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/education/edlife/what-to-do-with-those-leftover-meal-plan-swipes.html.

- 20. [Accessed 24 October, 2016];College and University Food Bank Alliance Web site. Available at: http://www.cufba.org/

- 21.Definitions of food security. [Accessed October 24, 2016];USDA Economic Research Service Web site. Updated October 4 2016. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx.

- 22.Farahbakhsh J, Ball GD, Farmer AP, et al. How do student clients of a university-based food bank cope with food insecurity? Can J Diet Pract Res. 2015;76(4):200–203. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2015-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farahbakhsh J, Hanbazaza M, Ball GD, et al. Food insecure student clients of a university-based food bank have compromised health, dietary intake and academic quality. Nutr Diet. 2016 doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsley K, King C. [Accessed July 10, 2016];Food insecurity of campus-residing Alaskan college students. [poster] Published 2013. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277300658_Food_Insecurity_of_Campus-Residing_Alaskan_College_Students_Poster_Session.

- 25.Nelson M. [Accessed July 17, 2016];Food insecurity among Anchorage Alaskan campus-residing college students. Academia Web site. Published 2015. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/22325211/Food_Insecurity_Among_Anchorage_Alaskan_Campus-Residing_College_Students.

- 26.Wintz R, Chriest N. [Accessed June 4, 2016];Food insecurity within the University student population A survey at the University of Alaska Anchorage. Available at: https://www.uaa.alaska.edu/academics/honors-college/ours/opportunities/research/_documents/wintz-rachel-and-chriest-nathaniel-ugr.pdf.

- 27. [Accessed May 27, 2016];Spring 2015 Food Insecurities Survey Results. Published 2015. Available at: http://www.mtu.edu/huskyfan/learn/survey-spring-2015.pdf.

- 28. [Accessed June 13, 2016];Food insecurity: Results and progress. Michigan Tech. Available at: http://megaslides.com/doc/7847141/

- 29.Chaparro MP, Zaghloul SS, Holck P, Dobbs J. Food insecurity prevalence among college students at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(11):2097–2103. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009990735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin MT, Peters RJ, Jr, Ford K, et al. The relationship between perceived psychological distress, behavioral indicators and African-American female college student food insecurity. Am J Health Stud. 2013;28(3):127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton-López MM, López-Cevallos DF, Cancel-Tirado DI, Vazquez L. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among students attending a midsize rural university in Oregon. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanna L. Evaluation of food insecurity among college students. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2014;4(4):46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaines A, Robb CA, Knol LL, Sickler S. Examining the role of financial factors, resources and skills in predicting food security status among college students. Int J Consum Stud. 2014;38(4):374–384. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maroto ME, Snelling A, Linck H. Food insecurity among community college students: Prevalence and association with grade point average. Community Coll J. 2015;39(6):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva MR, Kleinert WL, Sheppard AV, et al. The relationship between food security, housing stability, and school performance among college students in an urban University [abstract]. [published online ahead of print December 14 2015} J Coll Stud Ret. 2015 http://csr.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/12/11/1521025115621918.abstract.

- 36.Bruening M, Brennhofer S, van Woerden I, et al. Factors related to the high rates of food insecurity among diverse, urban college freshmen. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):1450–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris LM, Smith S, Davis J, Null DB. The prevalence of food security and insecurity among Illinois University students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(6):376–382.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munro N, Quayle M, Simpson H, Barnsley S. Hunger for knowledge: food insecurity among students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Perspect Educ. 2013;31(4):168–179. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassier S, Veldman F. Food security status and academic performance of students on financial aid: the case of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Alternation (Durb) 2013;9:248–264. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van den Berg L, Raubenheimer J. Food insecurity among students at the University of the Free State, South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr. 2015;28(4):160–169. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes R, Serebryanikova I, Donaldson K, Leveritt M. Student food insecurity: The skeleton in the university closet. Nutr Diet. 2011;68(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Micevski DA, Thornton LE, Brockington S. Food insecurity among university students in Victoria: A pilot study. Nutr Diet. 2014;71(4):258–264. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallegos D, Ramsey R, Ong KW. Food insecurity: is it an issue among tertiary students? J High Educ. 2014;67(5):497–510. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nur Atiqah A, Norazmir M, Khairil Anuar M, et al. Food security status: It's association with inflammatory marker and lipid profile among young adult. Int Food Res J. 2015;22(5):1855–1863. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nugent MA. Journeys to the food bank: Exploring the experience of food insecurity among post-secondary students [thesis] Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada: University of Lethbridge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Booth A. [Accessed July 26, 2016];Anybody could be at risk: Food (in)security within the University of Northern British Columbia [report]. Published March 2016. Available at: http://www.cupe3799.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Food-Security-at-UNBC-Final-2016-Report-2.pdf.

- 47.Walsh K. Understanding students' accessibility and barriers to nourishing food [internship project] University of Canterbury; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anaya-Loyola M, Gonzalez-Martinez M, Aguilar-Galarza B, et al. Food insecurity is related to obesity and lipid alterations in Mexican college students [abstract] FASEB J. 2014;28(1) (suppl 805.2) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koller K. Extent of BGSU student food insecurity and community resource use [honors project] Bowling Green State University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldrick-Rab S, Broton K, Eisenberg D. [Accessed July 16, 2016];Hungry to learn: Addressing food & housing insecurty among undergraduates. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Published 2015. Available at: http://wihopelab.com/publications/Wisconsin_hope_lab_hungry_to_learn.pdf.

- 51.Gorman A. Food insecurity prevalence among college students at Kent State University [thesis] Kent State University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Espinoza A. Assessing differences in food security status among college students enrolled at a public California State University campus [thesis] Fresno, California State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burns-Whitmore B, Carmona V. [Accessed July 15, 2016];The prevalence of food insecurity among students at California State Polytechnic University (Cal Poly Pomona) [abstract]. Published 2012. Available at: http://sccur.csuci.edu/abstract/viewabstract/the-prevalence-of-food-insecurity-among-students-at-california-state-polytechnic-university-cal-poly-pomona.htm.

- 54.Maguire J, O'Neill M, Aberson C. [Accessed July 13, 2016];California State University Food and Housing Security Survey: Emerging patterns from the Humboldt State University data. Published 2016. Available at: http://hsuohsnap.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ExecutiveSummary.docx1-14-16.pdf.

- 55.Maroto M. Food insecurity among community college students: prevalence and relationship to GPA, energy, and concentration [dissertation] Morgan State University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacDonald A. Food insecurity and educational attainment at the University of Arkansas [honors thesis] University of Arkansas; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Key Statistics & Graphics. [Accessed June 23, 2016];USDA Economic Research Service Web site. Published 2016. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics/#foodsecure.

- 58.Rosier K. [Accessed October 24, 2016];Food insecurity in Australia: What is it, who experiences it and how can child and family services support families experiencing it? Australian Institute of Family Studies Web site. Published 2011. Available at: https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/food-insecurity-australia-what-it-who-experiences-it-and-how-can-child.

- 59.Food Security & Systems. [Accessed October 24, 2016];Activity & Nutrition Aotearoa Web site. Available at: http://ana.org.nz/resource-category/food-security/

- 60.du Toit D. [Accessed October 24, 2016];Food Security agriculture, forestry, and fisheries. Directorate Economic Services Web site. Published 2011. Available at: http://www.nda.agric.za/docs/genreports/foodsecurity.pdf.

- 61.Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J Nutr. 2004;134(6):1432–1438. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.##. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chilton M, Booth S. Hunger of the body and hunger of the mind: African American women’s perceptions of food insecurity, health and violence. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(3):116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cook JT, Frank DA. Food security, poverty, and human development in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136(1):193–209. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willows ND, Au V. Nutritional quality and price of university food bank hampers. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2006;67(2):104–107. doi: 10.3148/67.2.2006.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jessri M, Abedi A, Wong A, Eslamian G. Nutritional quality and price of food hampers distributed by a campus food bank: a Canadian experience. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(2):287–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riches G. Food banks and food security: welfare reform human rights social policy. Lessons from Canada? Soc Policy Adm. 2002;36(6):648–663. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martin KS, Wu R, Wolff M, et al. A novel food pantry program: food security, self-sufficiency, and diet-quality outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(5):569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) [Accessed October 24, 2016];USDA Food and Nutrition Service Web site. Published 2016. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/facts-about-snap.

- 70. [Accessed July 15, 2016];Assembly passes higher education measures. Published 2016. Available at: http://asmdc.org/members/a17/news-room/press-releases/assembly-passes-higher-education-measures.