Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication. The anterior insula (AI) participates in emotional salience detection; and the posterior insula (PI) participates in sensorimotor integration and response selection. Meta-analyses have noted insula-based aberrant connectivity within ASD. Given the observed social impairments in ASD and the role of the insula in social information processing (SIP), investigating functional organization of this structure in ASD is important. We investigated differences in resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) using fMRI in male youths with (N=13; mean = 14.6 years; range: 10.2–18.0 years) and without ASD (N=17; mean = 14.5 years; range: 10.0–17.5 years). With seed-based FC measures, we compared RSFC in insular networks. Hypoconnectivity was observed in ASD (AI-superior frontal gyrus (SFG); AI-thalamus; PI-inferior parietal lobule (IPL); PI-fusiform gyrus (FG); PI-lentiform nucleus/putamen). Using the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) to assess social functioning, regression analyses yielded negative correlations between SCQ scores and RSFC (AI-SFG; AI-thalamus; PI-FG; PI-IPL). Given the insula’s connections to limbic regions, and its role in integrating external sensory stimuli with internal states, atypical activity in this structure may be associated with social deficits characterizing ASD. Our results suggest further investigation of the insula’s role in SIP across a continuum of social abilities is needed.

Keywords: Anterior insula, Posterior insula, Autism spectrum disorder, Neurodevelopment, Resting-state functional connectivity, Salience network, Social communication questionnaire

1. Introduction

One of the defining characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs), a heterogenous group of lifelong neurodevelopmental disorders, is impaired social interaction and communication (American Psychiatric Association., 2013). One hypothesis suggests that the heterogeneity observed in ASD may arise from variation in connectivity within and between brain networks (Ebisch et al., 2011). The role of atypical brain connectivity in the ontogeny of ASD has been under investigation for several decades and findings have been inconsistent across regions; both hyper- and hypo- connectivity in individuals with ASD has been indicated. For example, hypoconnectivity has been noted in language, executive function, and social cognition, whereas hyperconnectivity has been reported in emotion processing, memory, and language (Uddin et al., 2013).

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) has emerged as a practical means of investigating functional connectivity (FC) in individuals with ASD. Rs-fMRI allows for investigation of underlying intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs; Seeley et al., 2007). These networks: (i) are defined by structures that are functionally connected by ongoing, coherent, spontaneous activity (Biswal et al., 1995; Damoiseaux et al., 2006); (ii) support complex mental processes such as language, executive function, and salience detection (Doll et al., 2015); (iii) are not confounded by performance or strategy differences between clinical and non-clinical populations (Nomi and Uddin, 2015); and (iv) are replicable and stable across individuals and studies (Di Martino et al., 2009; Menon and Uddin, 2010).

Atypical connectivity has been shown reliably in four ICNs in ASD, namely - the right and left executive control (rECN and lECN), default-mode (DMN), and salience (SN) networks (See Abbott et al., 2016 for review). While ECN (“task-positive” network) and DMN (“task-negative” network) show strong anti-correlation in healthy adults (Seeley et al., 2007), this relationship between ECN and DMN is reduced in individuals with ASD (Rudie et al., 2012). Furthermore, within-network hypoconnectivity has been observed in the ECN (Kana et al., 2007; Solomon et al., 2009; Solomon et al., 2014) and both hypo- and hyper- connectivity have been reported within the DMN in ASD (Monk et al., 2009; von dem Hagen et al., 2013; Weng et al., 2010). Decreased connectivity has also been shown within the SN in ASD (Ebisch et al., 2011; Kana et al., 2007) and between SN nodes and the amygdala subserving emotional experience (von dem Hagen et al, 2013). The SN is thought to modulate ECN and DMN (Sridharan et al., 2008) and this network may link neocortical processing networks with limbic and autonomic systems, associating motivational “value” with these processes (Dosenbach et al., 2007; Seeley et al., 2007).

Converging evidence from neuroimaging in ASD indicates that the insula may be a critical component of the SN as it integrates external sensory stimuli with internal states (Odriozola et al., 2016; Seeley et al., 2007; Uddin and Menon, 2009). In both humans and non-human primates, the insula has three distinct cytoarchitectonic regions: the anterior agranular area, the posterior granular area, and the transitional dysgranular zone (Augustine, 1985, 1996; Mesulam and Mufson, 1982). Moreover, functional subregions corresponding to these regions of the insula have been identified (Chang et al., 2013; Deen et al., 2011; Farb et al., 2013). The anterior insula (AI) is associated with chemo-sensation, experience of emotion, emotional salience detection, and higher level cognitive tasks and executive control (Chang et al., 2013; Menon and Uddin, 2010; Seeley et al., 2007). The posterior region of the insula (PI) is associated with sensorimotor integration, body orientation, environmental monitoring, pain, and response selection (Chang et al., 2013; Deen et al., 2011; Menon and Uddin, 2010; Seeley et al., 2007).

The anterior insula has been identified as a consistent locus of hypoactivity in ASD (Di Martino et al., 2009). Notably, Deen et al. (2011) utilized rs-fMRI and cluster analysis to investigate functional subregions of the insula in non-clinical adult participants, delineating two anterior insular regions, ventral (vAI) and dorsal (dAI). Ventral AI was associated with emotion processing and the related physiological responses (e.g., heart rate and galvanic skin response), with the strongest correlations between the vAI and pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (pACC). Additionally, connectivity was found between vAI and much of the insula, the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), dorsal ACC (dACC), and the anterior and posterior sections of the superior temporal sulcus (STS). Dorsal AI was highly connected to dorsal ACC; the dAI-dACC network is associated with cognitive control and decision making. Other regions correlated with dAI include the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), supramarginal gyrus, ventral precentral sulcus, and the anterior IFG. These findings were later replicated by Chang et al. (2013) using a technique that combined resting-state connectivity-based parcellation with large-scale meta-analysis. Farb et al. (2013) examined AI as a whole while distinguishing exteroception (awareness of external stimuli) and interoception (monitoring of internal bodily cues); AI was associated with exteroceptive attention, and activity in the region was better predicted by attention to external stimuli. The posterior insula is functionally connected to the primary and secondary motor and somatosensory cortices (Deen et al., 2011), receiving afferent projections from the lamina I spinothalamocortical pathway carrying nociceptive, thermal, and other interoceptive information (Craig, 2002, 2009; Farb et al., 2013). Connectivity analysis showed PI correlations with the entire insula, SMA, pre-SMA, precentral and postcentral gyri, the medial thalamic region, dACC, and anterior IFG (Chang et al., 2013; Deen et al., 2011).

Despite numerous reports of aberrant brain connectivity across multiple regions in ASD, the nature and extent of these differences remain poorly understood (See Dickstein et al., 2013; Duerden et al., 2012 for meta-analyses). Atypical activity and connectivity within the neurocircuitry and structures that integrate internal and external information may underlie the ASD characteristic of impaired social information processing (Ebisch et al., 2011). Accordingly, the insula is well-positioned to serve as a nexus for multimodal integration and to assign salience to stimuli. In order to better understand the role of the insula in ASD, we examined differences in intrinsic FC in adolescents with and without ASD along with measures of their social functioning. Based on the extant literature, we predicted hypoconnectivity between the insula and other regions in individuals with ASD such that those with increased brain connectivity (i.e., similar to the typically-developing controls; TDC) would demonstrate improved behavioral outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants with and without ASD were recruited from University of Minnesota (UMN) clinics, local and regional participant registries, UMN websites, and local advertising. All participants were recruited with the approval of the UMN Institutional Review Board and were provided with a written description of the study to obtain informed consent from the parent. Forty participants were recruited to complete the imaging study. Ten individuals (8 ASD, 2 TDC) had to be excluded from analysis due to motion (details in Section 2.2). The final analyses from the 30 individuals included two groups. Individuals with ASD (N = 13; age ± SD: 14.6 ± 3.2 years; range: 10.2–18.0 years) were age-matched with individuals without ASD (N = 17; age ± SD: 14.5 ± 2.2 years; range: 10.0–17.5 years). The sample is further described in Table 1. ASD clinical history and records were reviewed for each participant and criteria were based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) classifications for ASD (autism, Asperger disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)). Additional medical history was obtained from a parent. Exclusion criteria were: known genetic syndromes related to developmental delays, known or suspected brain malformation, metabolic disorders, CNS infections, vision, hearing or motor impairments, and MRI incompatibilities (e.g., implanted medical device, braces, etc.). Potential participants in the TDC group were excluded if they had a history of special education or developmental delay.

Table 1.

Description of the analyzed sample. This table displays demographic data and other descriptors including head motion (translation and rotation) of the analyzed sample. Student’s t-tests were conducted to note significant differences between the groups.

| ASD (N = 13) | Controls (N = 17) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.6 years (SD: ± 3.2 years; Range: 10.2–18.0y) | 14.5 years (SD: ± 2.2 years; Range: 10.0–17.5y) | p= 0.88 |

| SCQ | |||

| Total | 18.0 (SD: ± 7.3) | 1.9 (SD: ± 2.1) | p = 1.8 * 10−5 |

| Communication | 6.6 (SD: ± 3.1) | 1.0 (SD: ± 1.2) | p = 8.0 * 10−6 |

| Restricted/repetitive behaviors | 5.1 (SD: ± 2.8) | 0.3 (SD: ± 0.8) | p = 6.9 * 10−5 |

| Social interaction | 7.2 (SD: ± 3.8) | 0.5 (SD: ± 0.5) | p = 2.5 * 10−5 |

| Head motion parameters | |||

| Roll (degrees) | 3.9 * 10−4 (SD: ± 1.8 *10−3) | −2.1 * 10−4 (SD: ± 1.3 * 10−3) | p= 0.30 |

| Pitch (degrees) | −3.4 * 10−4 (SD: ± 1.3* 10−3) | 2.6 * 10−4 (SD: ± 1.2 * 10−3) | p= 0.20 |

| Yaw (degrees) | 7.3 * 10−5 (SD: ± 1.5 *10−3) | −3.0 * 10−4 (SD: ± 1.2 * 10−3) | p= 0.46 |

| Superior-inferior translation (dS; mm) | −2.6 * 10−4 (SD: ± 7.0* 10−4) | 1.1 * 10−4 (SD: ± 8.4 * 10−4) | p= 0.21 |

| Left-right translation (dL; mm) | 8.8 * 10−5 (SD: ± 8.0 *10−4) | −2.8 * 10−4 (SD: ± 8.3 * 10−4) | p= 0.23 |

| Anterior-posterior translation (dP; mm) | −3.8 * 10−4 (SD: ± 1.0* 10−3) | −8.8 * 10−4 (SD: ± 8.2 * 10−3) | p= 0.15 |

2.2. MRI data acquisition

Imaging data was collected using a Siemens TIM Trio 3T scanner (Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil. The sequence parameters were: multi-band gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (MB-EPI) multiband factor (MB) = 4260 volumes, repetition time (TR) = 1320 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, 64 contiguous AC-PC aligned axial slices, voxel size = 2 × 2 × 2 mm, matrix = 106 × 106. During fMRI acquisition participants were instructed to close their eyes, lie still, relax, and not fall asleep. High resolution T1-weighted anatomical scans were acquired using a magnetization prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence. Shaped foam was used to reduce head movement and increase comfort. In addition, a short MB-EPI scan with opposite phase encoding was acquired just prior to the rest scan and used with the FSL tools topup and applytopup (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/topup) to correct fMRI data for geometric distortion caused by magnetic field inhomogeneities.

All major sources of artifacts were removed while preserving the integrity of the continuous time series. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was used to decompose individual preprocessed 4D data sets into different spatial and temporal components (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/MELODIC). Dimensionality of the ICA reduction was automatic. Independent components defined by ICA (FSL MELODIC) were classified as noise using spatial and temporal characteristics detailed in the MELODIC (FSL) manual (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fslcourse/lectures/melodic.pdf) and described in Kelly et al. (2010) and Xu et al. (2014). Noise included head motion (e.g., “rim-like” artifacts around the brain, spikes in time series), scanner artifacts (e.g., slice dropouts, high frequency noise, field inhomogeneities), and physiological noise (e.g., respiration, cardiac frequencies, white matter signal, ventricular/cerebrospinal fluid fluctuations, frontal air cavities, ocular structures). From the preprocessed data, signal was subtracted from noise components. Eight individuals with ASD and two TDC were excluded from the study because motion correction output showed more than 1.8 mm of movement or > 50% of the ICA components were identified as movement related. Additionally, we examined rotation and translation motion parameters from the 30 completed participants. No significant motion parameter differences were observed between the groups (ASD and TDC; Table 1). Further, we did not find significant correlations between ASD traits as measured by the SCQ and motion parameters in the whole sample.

2.2.1. Regions of interest (ROIs) selection and seed generation

Regions of interest (ROIs), anterior and posterior divisions of the insula, were created by placing spherical seeds at coordinates used by Cauda and colleagues (See Table 1 in Cauda et al, 2011). Briefly, Cauda and colleagues drew ten 5 × 5 × 5 mm3 cubic seeds along the insular surface based upon anatomical images (See Fig. 1 and Table 1 in Cauda et al, 2011). We placed spherical seeds (3 mm radius) at each coordinate that corresponded to the anterior and posterior insula networks (anterior network: seeds 1, 2, 4, 5, and 8; posterior network: seeds 3, 7, and 10). Corresponding ROIs were used to create both right and left insulae, which did not differ. We analyzed the right and left insulae together, as we did not have an a priori laterality hypothesis. In addition, we minimized the number of multiple comparisons by not separating the regions, all anterior ROIs and all posterior ROIs were collapsed into one corresponding region. Average time-series were extracted separately for anterior and posterior insula by computing the mean intensity for all voxels within each seed region for each time point in the denoised residual data.

2.2.2. Individual-level analyses

Analyses were performed using the protocol described in Camchong et al. (2014). Specifically, all imaging data was preprocessed using analysis of functional neuroimages (AFNI) and FMRIB Software Libraries (FSL; Oxford, United Kingdom). Preprocessing consisted of: Dropping first three volumes to account for magnetic field homogenization; B0 field map unwarping, slice time correction; 3-dimensional motion correction (AFNI: 3dvolreg); skull stripping; spatial smoothing (with a 6 mm full-width half-maximum kernel); grand mean scaling, high-pass temporal filtering (100 Hz) to remove correlations associated with slow trends scanner noise, and registration of all images to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 standard space. Three-dimensional motion correction calculation provided motion correction parameters for each participant for translation in the x, y, and z planes and for rotation (pitch, roll, and yaw).

2.3. Resting-state analysis

2.3.1. Individual-level analyses

A multiple regression analysis on the denoised data was performed using AFNI between the extracted average time-series from each seed and all voxels in the brain. This generated a map containing correlation coefficients (r) for each voxel, for each individual, for each seed, for both the ASD and control groups. Correlation coefficients were standardized by transforming r to z-scores. These z-maps showed the degree of correlations with the corresponding seed averaged time-series for each seed for each participant for both groups.

2.3.2. Group-level analyses

To investigate RSFC differences between individuals with ASD and those without, we conducted an independent samples t-test (whole-brain analysis) using AFNI (3dttest++) for each seed (anterior and posterior insula). To control for potential false-positives (Eklund et al., 2016) when calculating cluster-size thresholding, data was not assumed to have a Gaussian smoothness. Non-gaussian smoothness of the data was estimated using the “-ClustSim” option within 3dttest++, which generated a table of cluster-size thresholds for a range of per-voxel p-value threshold and a range of cluster-significance values (Cox et al., 2017). This table was generated by (i) computing the residuals of the model at each voxel at the group level and (ii) generating a null distribution by randomizing among subjects the signs of the residuals in the test, repeating the t-tests, and iterating 10,000 times. From the table of cluster-size threshold, based on a p-value threshold of 0.005 and keeping the probability of getting a single noise-only cluster at 0.01 or less, the cluster-size threshold needed to be of 825 voxels for AI and 899 voxels for PI group difference t-maps. As mentioned before, age may have a moderating effect in ASD. Therefore, we included age in all group-level investigations.

2.3.3. SCQ

To investigate possible associations between specific brain RSFC patterns and ASD traits we conducted a regression analysis similar to earlier studies (Cullen et al., 2016; Gilmore et al., 2016; Schulz et al., 2013). We used the Social Communication Questionnaire-Lifetime (SCQ; Berument et al., 1999; Rutter et al., 2003), a 40-item questionnaire completed by the parent or caregiver that was originally designed as a screening tool for children (older than or at least 4 years of age) and derived from the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al., 1994). The SCQ is strongly correlated with the ADI-R (r = 0.71, p < .001; Berument et al. 1999). Items on the SCQ correspond to criteria for autism from the DSM-IV (APA, 2000) and include questions assessing reciprocal social interaction, language and communication, and repetitive, stereotyped patterns of behavior. Although the suggested cut-off score to suggest clinical concerns is ≥15 (Berument et al., 1999; Rutter et al., 2003), more recent reports indicate that a cut-off score ≥11 maximizes sensitivity and specificity, particularly in younger groups (Allen et al., 2007, Corsello et al., 2007, Eaves et al., 2006, Rosenberg et al., 2018, Schanding et al., 2012, Snow and Lecavalier, 2008, Wiggins et al., 2015, 2016). Further, when used with population-based control groups (Mulligan et al., 2009, Rosenberg et al., 2018) SCQ data indicate the presence of ASD traits distributed continuously throughout the general population. In fact, Mulligan et al. (2009) reported that some individual items on the SCQ were answered as “autism-positive” for up to 41.8% of children in a general population sample of school-age children. Given the age-range and size of our sample, we opted to view SCQ scores as a continuous variable. We initially recruited participants categorically, those with ASD diagnoses and TDC, and we expected our SCQ data to clearly delineate these dichotomous groups. Although, a screening tool such as the SCQ should only be used to identify at-risk individuals before in-depth clinical evaluations, evaluating the scores as a continuous variable provided a proxy for ASD trait severity in our connectivity analysis. Multiple linear regression analyses using the AFNI-3dRegAna program were conducted to correlate SCQ scores with RSFC data for all participants. F-statistic maps, which showed the strength of linear regressions, were thresholded and clustered correcting for multiple comparisons (2-tailed, p < 0.025 significance used for correlations). Prior to analysis these scores were not demeaned or centered.

3. Results

3.1. Group differences

A t-test was performed to note any significant differences between the groups. No significant differences were observed in age (p = 0.88). As expected, there were significant differences in SCQ scores between the groups. Individuals without ASD scored lower on average than individuals with ASD across all subsections and the total (p < 0.001; Table 1). Significant RSFC differences were also observed between the ASD and TDC groups. Significantly lower RSFC was observed in the ASD group between the AI and superior frontal gyrus (SFG; bilateral; Fig. 1A–B) and thalamus (right; Fig. 1C–D) when compared to the non-ASD sample (p < 0.001). Likewise, there was lower RSFC observed in the ASD group between PI and inferior parietal lobule (IPL; bilateral; Fig. 2A–B), fusiform gyrus (FG; left; Fig. 2C–D), and lentiform nucleus/putamen (right; Fig. 2E–F) when compared to TDC (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

A–E – Anterior Insula Seed. (A–B) A significant difference (B, p = 1.2 * 10−4) in resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) between the anterior insula (AI) and the superior frontal gyrus (SFG, *) was observed between the two groups. This difference was noted bilaterally (SFG coordinates: left −25, 43, 22; right 28, 45, 31). The ASD group had lower RSFC as compared to the non-clinical sample. (C–D) A significant difference (D, p = 1.7 * 10−4) in RSFC between the AI and the thalamus (**) were observed between the two groups (thalamus coordinates: 12, −16, 11). The ASD group had lower RSFC as compared to the non-clinical sample. (E) The green highlights the AI (‡) seed that was used for analysis. (Error bars are ± 1SE. ASD = blue, Control = green).

Fig. 2.

A–F – Posterior Insula Seed. (A–B) A significant difference (B, p=1.4 * 10−4) in RSFC between the posterior insula (PI) and the left fusiform gyrus (FG, *) in the temporal cluster were observed between the two groups (FG coordinates: −45, −50, −16). The non-clinical group had increased RSFC as compared to the ASD sample. (C–D) A significant difference (D, p = 4.2 * 10−4) in RSFC between the PI and the right lentiform nucleus/putamen (**) was observed between the two groups (Lentiform nucleus/putamen coordinates: 28, 0, −1). The non-clinical group had higher RSFC as compared to the ASD sample. (E-F) Significant differences (F, p = 4.5 * 10−4) in RSFC were observed between the PI and both the left and right inferior parietal lobule (IPL, †; coordinates: −53, −40, 39; 55, −40, 39, respectively). (G) The green highlights the PI (‡) seed that was used for analysis. (Error bars are ± 1SE. ASD = blue, Control = green).

3.2. SCQ

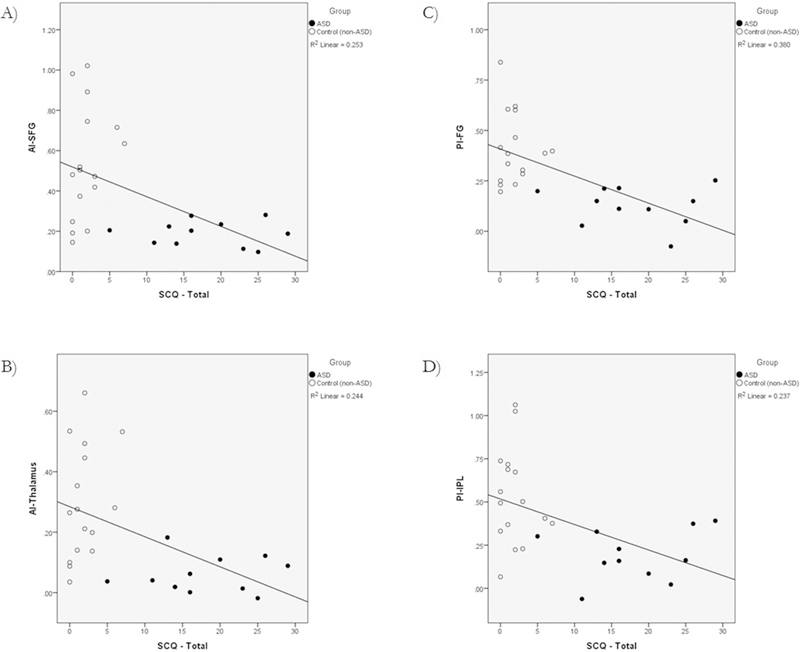

Regression analysis was performed to explore associations between ASD traits and specific brain RSFC. With both groups combined we found and confirmed lower SCQ scores (fewer ASD traits) to be associated with higher RSFC between the insula and several of the aforementioned regions. After Bonferroni correction (p ≤ 0.05/5 or 0.01), we observed significant correlations between: AI and SFG, AI and the thalamus, PI and FG, and PI and IPL (Fig. 3A–D).

Fig. 3.

A–D – SCQ and RSFC. A regression analysis using SCQ scores as a continuous variable was performed. SCQ scores were significantly correlated with RSFC (z-scores) between: (A) AI to SFG (R2 = 0.253; p = 0.007), (B) AI to thalamus (R2 = 0.244; p = 0.009), (C) PI to FG (R2 = 0.380; p = 0.001), and (D) PI to IPL (R2 = 0.237; p = 0.010).

3.3. Age

We examined the RSFC data for age effects and found significant correlations between participant age (mean-centered) and RSFC in the PI seed of the ASD group such that functional connectivity increased with age between the PI and FG, lentiform/putamen, and IPL (mean-centered age is depicted in Fig. 4A–C). These correlations survived Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05/5 or 0.01). No significant age effects were observed in the AI seed of the ASD group. Further, no ageeffects were found in the non-ASD group.

Fig. 4.

A–C – Age (mean-centered) and RSFC in the ASD group. Mean-centered age significantly correlated with RSFC in the PI of the ASD group. The correlations were: (A) PI to FG (R2=0.746; p=0.003), (B) PI to lentiform nucleus/putamen (R2=0.812; p=0.001), and (C) PI to IPL (R2=0.723; p=0.005). All correlations p < 0.01 (Bonferroni correction: p = 0.05/5) are shown.

4. Discussion

This study examined RSFC of the insula, a putative nexus of the SN associated with modulating activation between the ECN and DMN and linking neocortical processing with the limbic system, in adolescents with and without ASD. Discrete functions have been identified for the anterior and posterior regions of the insula; the anterior insula, has been associated with emotional salience detection and attentional control while the posterior insula has been implicated in sensorimotor integration, body orientation, environmental monitoring, and response selection. In the ASD group, decreased connectivity was noted between AI and both the right thalamus and bilateral middle SFG. Hypoconnectivity was also noted between PI and bilateral IPL, as well as the left FG, and the right lentiform nucleus/putamen when compared to individuals without ASD. Regression analyses using SCQ scores across the sample (ASD and TDC) revealed that lower SCQ scores were associated with higher RSFC between AI and SFG and thalamus, and between PI and FG and IPL. We also observed a significant positive correlation between age and posterior insula RSFC (PI-FG, PI-lentiform/putamen, PI-IPL) in the ASD group.

Our findings are consistent with prior reports of functional hypoconnectivity in ASD, specifically, decreased FC between and within intrinsic networks that include structures associated with the social brain (Ebisch et al., 2011; von dem Hagen et al., 2013); hypoconnectivity between the insula and social processing regions (Just et al., 2007; Kana et al., 2007; Koshino et al., 2008); and hypoconnectivity in frontal and posterior-temporal cortical areas involved in social-affective information processing (Vissers et al., 2012). We noted decreased RSFC between AI and the thalamus, aberrant connectivity between these regions may subserve social and communication deficits in ASD related to sensory systems such as touch, proprioception, and interoception. The accurate interpretation of tactile cues is vital during social interactions as they provide pertinent information about emotion, attachment, compliance, and intimacy (Failla et al., 2017; Foss-Feig et al., 2012). Moreover, AI and SFG are key components of the cingulo-opercular (CO) network, which comprises the dorsal anterior cingulate/medial superior frontal cortex and bilateral anterior insula/frontal operculum. Critical for task control, regions of the CO network are associated with signals related to control initiation, control maintenance, as well as feedback and adjustment (e.g., error signals) across a wide range of tasks (Dosenbach et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2010). Compromised connectivity within this network may impact cognitive control and goal-directed behavior in ASD. Additionally, reduced FC between PI and brain regions (e.g., IPL, FG, putamen) involved in emotional, sensory processing, and motor control provide further support for connectivity-based theories of ASD (Just et al., 2004; Kana et al., 2011). For example, hypoconnectivity between the PI and bilateral IPL may manifest in impaired detection of visually-salient stimuli (Uddin et al., 2010). Disturbances in PI connectivity to the SMA and putamen correspond to functional deficits in ASD associated in action execution and sensory perception (Kelly et al., 2012). Also, the FG is considered a key structure for functionally-specialized computations of high-level vision such as face perception, object recognition, and reading (Grill-Spector et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016); PI-FG hypoconnectivity may subsume perceptual deficits in ASD related to recognition of salient stimuli.

Exploratory analyses were conducted to investigate possible relationships between RSFC and ASD traits across the population (ASD and TDC samples). Initially, we applied SCQ scores as an exclusion criterion for the non-ASD group, and to further define the ASD group. However, because subclinical levels of ASD traits are observed in the general population, we drew from prior approaches (e.g., Mulligan et al., 2009) and assessed SCQ scores as a continuous variable to examine correlations between ASD traits and RSFC. Additionally, previous studies have shown links between behavioral measures and FC during rest (Green et al., 2016; Seeley et al., 2007; Weng et al., 2010). Our analysis revealed fewer ASD traits were associated with higher RSFC between AI and SFG and thalamus, and between PI and FG and IPL. The negative correlations we observed within the SN, which includes the insula, are consistent with previous studies; Abbott et al. (2016) found decreased connectivity within the SN network to be associated with more ASD symptoms as measured by the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), while increased connectivity within the DMN was associated with more executive impairments within an ASD group. Weng et al. (2010) used the ADI-R to examine the relationship between ICNs and the core symptoms of ASD and found increased social skill deficits and RRBs to be associated with decreased connectivity within the DMN, including connectivity between posterior cingulate cortex and the SFG in an ASD group. Green et al. (2016) examined sensory overresponsivity (SOR), a common condition in ASD, and atypical activity in SN, reporting higher levels of SOR correlated with greater RSFC within the SN, including between the right AI and sensori-motor cortical areas. Investigating the relationship between behavioral measures and RSFC provides us with critical insight into brain responses during active processing, as ICNs are closely linked with active processes.

Limitations:

(1) Our sample consisted of only male participants. Given our limited sample size and the well-documented high male-to-female ASD ratio, we opted to exclude females to reduce variability. However, because ASD can present differently across the sexes, future studies will need to include females to further understand possible underlying genetic, structural, and network differences. (2) Although our analyses revealed an age effect in our ASD group, we did not collect developmental measures beyond age and are thus limited in our ability to address developmental change. Including biological measures of puberty may provide further insight into how behavioral and brain variables interact in the ASD timeline. Also, examining multiple age-ranges to clarify the role of development in our findings is warranted. Previous work with typically-developing individuals (Dennis et al., 2014) examined how the connectivity of the insula develops between the ages 12 and 30; they reported a decrease in fiber density between the insula and frontal and parietal cortices and an increase in fiber density between the insula and temporal cortex with age. Moreover, prior investigations (See Uddin et al, 2013 for review) have reported hyperconnectivity in children with ASD relative to TDC (≤11 years), hypoconnectivity in adolescents (~11–18 years) with ASD; and either hypoconnectivity or comparable connectivity in adults (>18 years) with and without ASD (Alaerts et al., 2015; Bos et al., 2014; Nomi and Uddin, 2015; Uddin et al., 2013). Thus, we would expect to find differences in connectivity between our regions of interest across age group and diagnosis. Future work examining changes based upon pubertal measures will allow us to delineate developmental age groups more precisely during critical periods when hormonal maturation taxes an already vulnerable system in ASD (Picci and Scherf, 2015). (3) We used 3 mm radius, spherical seeds that corresponded to locations described in Cauda et al (2011). While punctate in nature, our seeds extensively covered the insula from anterior to posterior without including areas of nearby structures such as the striatum (supplementary Fig. 1). Our spherical seeds have a similar radius to the 5 mm3 cubic seeds described by Cauda and colleagues. To examine the possibility of signal from nearby structures being included in their analysis, Cauda and colleagues increased (8mm3 seed; more than twice the thickness of the cortex) and reduced (3 mm3 seed; the thickness of the cortex) the size of their cubic seeds. They found both increasing and decreasing the size of the seeds yielded approximately the same results as the 5 mm3 seeds. While we have reduced the possibility of overlap with nearby structures by limiting size, we do recognize that future studies should continue to explore the effects of different seed sizes and shapes including single, continuous ROIs. (4) Our sample size was small so these findings should be considered preliminary until replicated. Finally, depending on study objectives (focal versus global), a more focal examination of the insula, its functional subregions, and its networks may help us to continue to discern the role of the insula in ASD.

Overall, our results augment and support the premise that individuals with ASD show atypical neural activity associated with measures of social interaction and hypoconnectivity in structures and networks associated with social information processing. In effect, altered activity in structures and networks that assign value to socially relevant stimuli may underlie the impairments in social interaction and communication that characterize ASD.

As we observe an increase in the prevalence of ASD (Baio et al., 2018), understanding the roles of neurocircuitry and brain structures at play in ASD becomes even more critical. Future studies should to be undertaken to continue to explore the role of ICNs, both task-positive and task-negative, within ASD. Use of imaging results as a clinical tool will require not only larger and more heterogenous samples, but clear confirmation that these traits are constant and relatively consistent. In addition, as we elucidate these networks further, we learn more about the underlying neurocircuitry of ASD, informing the development of improved treatments targeting specific circuits at specified developmental time points. Ultimately, investigation of these intricate networks and how their interactions contribute to ASD symptomology will serve to help improve therapeutic interventions for this complex set of disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics (SJ), UMF Autism Funds (SJ, KOL), and Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disorders Training Program T73MC12835 (SMF). Neuroimaging was also supported by National institutues of health (NIH) P41 EB015894 National Institutes of Health and P30 NS076408 grants. We value text editing assistance by Paige Espelien and laboratory assistance from Dan O’Keefe, Patricia Carstedt, and Maria Linn.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.12.003.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abbott AE, Nair A, Keown CL, Datko M, Jahedi A, Fishman I, et al. , 2016. Patterns of atypical functional connectivity and behavioral links in autism differ between default, salience, and executive networks. Cereb. Cortex 26, 4034–4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaerts K, Nayar K, Kelly C, Raithel J, Milham MP, Di Martino A, 2015. Age-related changes in intrinsic function of the superior temporal sulcus in autism spectrum disorders. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 1413–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CW, Silove N, Williams K, Hutchins P, 2007. Validity of the social communication questionnaire in assessing risk of autism in preschool children with developmental problems. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine JR, 1985. The insular lobe in primates including humans. Neurol. Res. 7, 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine JR, 1996. Circuitry and functional aspects of the insular lobe in primates including humans. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 22, 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, et al. , 2018. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years – autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 67, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berument SK, Rutter M, Lord C, Pickles A, Bailey A, 1999. Autism screening questionnaire: diagnostic validity. Br. J. Psychiatry 175, 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS, 1995. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos DJ, van Raalten TR, Oranje B, Smits AR, Kobussen NA, Belle J, et al. , 2014. Developmental differences in higher-order resting-state networks in autism spectrum disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 4, 820–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camchong J, Macdonald AW 3rd, Mueller BA, Nelson B, Specker S, Slaymaker V, et al. , 2014. Changes in resting functional connectivity during abstinence in stimulant use disorder: a preliminary comparison of relapsers and abstainers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 139, 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, D’Agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Geminiani G, Vercelli A, 2011. Functional connectivity of the insula in the resting brain. Neuroimage 55, 8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LJ, Yarkoni T, Khaw MW, Sanfey AG, 2013. Decoding the role of the insula in human cognition: functional parcellation and large-scale reverse inference. Cereb. Cortex 23, 739–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsello C, Hus V, Pickles A, Risi S, Cook EH Jr., Leventhal BL, et al. , 2007. Between a ROC and a hard place: decision making and making decisions about using the SCQ. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 48, 932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Chen G, Glen DR, Reynolds RC, Taylor PA, 2017. FMRI clustering in AFNI: false-positive rates redux. Brain Connect. 7, 152–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD, 2002. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD, 2009. How do you feel now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KR, Klimes-Dougan B, Vu DP, Westlund Schreiner M, Mueller BA, Eberly LE, et al. , 2016. Neural correlates of antidepressant treatment response in adolescents with major depressive disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 26, 705–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Smith SM, et al. , 2006. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13848–13853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen B, Pitskel NB, Pelphrey KA, 2011. Three systems of insular functional connectivity identified with cluster analysis. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1498–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis EL, Jahanshad N, McMahon KL, de Zubicaray GI, Martin NG, Hickie IB, et al. , 2014. Development of insula connectivity between ages 12 and 30 revealed by high angular resolution diffusion imaging. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 1790–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Shehzad Z, Kelly C, Roy AK, Gee DG, Uddin LQ, et al. , 2009. Relationship between cingulo-insular functional connectivity and autistic traits in neurotypical adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 891–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Pescosolido MF, Reidy BL, Galvan T, Kim KL, Seymour KE, et al. , 2013. Developmental meta-analysis of the functional neural correlates of autism spectrum disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 52, 279–289 e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll A, Holzel BK, Boucard CC, Wohlschlager AM, Sorg C, 2015. Mindfulness is associated with intrinsic functional connectivity between default mode and salience networks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Miezin FM, Cohen AL, Wenger KK, Dosenbach RA, et al. , 2007. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11073–11078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerden EG, Mak-Fan KM, Taylor MJ, Roberts SW, 2012. Regional differences in grey and white matter in children and adults with autism spectrum disorders: an activation likelihood estimate (ALE) meta-analysis. Autism Res. 5, 49–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LC, Wingert HD, Ho HH, Mickelson EC, 2006. Screening for autism spectrum disorders with the social communication questionnaire. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 27, S95–S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebisch SJ, Gallese V, Willems RM, Mantini D, Groen WB, Romani GL, et al. , 2011. Altered intrinsic functional connectivity of anterior and posterior insula regions in high-functioning participants with autism spectrum disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 1013–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund A, Nichols TE, Knutsson H, 2016. Cluster failure: why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, 7900–7905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Failla MD, Peters BR, Karbasforoushan H, Foss-Feig JH, Schauder KB, Heflin BH, et al. , 2017. Intrainsular connectivity and somatosensory responsiveness in young children with ASD. Mol. Autism 8, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farb NA, Segal ZV, Anderson AK, 2013. Attentional modulation of primary interoceptive and exteroceptive cortices. Cereb. Cortex 23, 114–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss-Feig JH, Heacock JL, Cascio CJ, 2012. Tactile responsiveness patterns and their association with core features in autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 6, 337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore CS, Camchong J, Davenport ND, Nelson NW, Kardon RH, Lim KO, et al. , 2016. Deficits in visual system functional connectivity after blast-related mild TBI are associated with injury severity and executive dysfunction. Brain Behav. 6, e00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, Hernandez L, Bookheimer SY, Dapretto M, 2016. Salience network connectivity in autism is related to brain and behavioral markers of sensory over-responsivity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 618–626 E611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Weiner KS, Kay K, Gomez J, 2017. The functional neuroanatomy of human face perception. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 3, 167–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ, 2007. Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry. Cereb. Cortex 17, 951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Minshew NJ, 2004. Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain 127, 1811–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Keller TA, Minshew NJ, Just MA, 2007. Inhibitory control in high-functioning autism: decreased activation and underconnectivity in inhibition networks. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Libero LE, Moore MS, 2011. Disrupted cortical connectvity theory as an explanatory model for autism spectrum disorders. Phys. Life Rev. 8, 410–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RE Jr., Alexopoulos GS, Wang Z, Gunning FM, Murphy CF, Morimoto SS, et al. , 2010. Visual inspection of independent components: defining a procedure for artifact removal from fMRI data. J. Neurosci. Methods 189, 233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, Toro R, Di Martino A, Cox CL, Bellec P, Castellanos FX, et al. , 2012. A convergent functional architecture of the insula emerges across imaging modalities. Neuroimage 61, 1129–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino H, Kana RK, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Minshew NJ, Just MA, 2008. fMRI investigation of working memory for faces in autism: visual coding and underconnectivity with frontal areas. Cereb. Cortex 18, 289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A, 1994. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 24, 659–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Uddin LQ, 2010. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, Weng SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, et al. , 2009. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage 47, 764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, 1982. Insula of the old world monkey. I. architectonics in the insulo-orbito-temporal component of the paralimbic brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 212 (1), 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan A, Richardson T, Anney RJ, Gill M, 2009. The social communication questionnaire in a sample of the general population of school-going children. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 178, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SM, Dosenbach NU, Cohen AL, Wheeler ME, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE, 2010. Role of the anterior insula in task-level control and focal attention. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 669–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomi JS, Uddin LQ, 2015. Developmental changes in large-scale network connectivity in autism. Neuroimage Clin. 7, 732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola P, Uddin LQ, Lynch CJ, Kochalka J, Chen T, Menon V, 2016. Insula response and connectivity during social and non-social attention in children with autism. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11, 433–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picci G, Scherf KS, 2015. A two-hit model of autism: adolescence as the second hit. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 3, 349–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA, Moody EJ, Lee LC, DiGuiseppi C, Windham GC, Wiggins LD, et al. , 2018. Influence of family demographic factors on social communication questionnaire scores. Autism Res. 11, 695–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudie JD, Shehzad Z, Hernandez LM, Colich NL, Bookheimer SY, Iacoboni M, et al. , 2012. Reduced functional integration and segregation of distributed neural systems underlying social and emotional information processing in autism spectrum disorders. Cereb. Cortex 22, 1025–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C, Berument S, 2003. Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ). Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Schanding GT Jr., Nowell KP, Goin-Kochel RP, 2012. Utility of the social communication questionnaire-current and social responsiveness scale as teacher-report screening tools for autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42,1705–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz CS, Camchong J, Romine A, Schlesinger A, Kuskowski M, Pardo JV, et al. , 2013. An exploratory study of the relationship of symptom domains and diagnostic severity to PET scan imaging in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 214, 161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. , 2007. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow AV, Lecavalier L, 2008. Sensitivity and specificity of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers and the Social Communication Questionnaire in preschoolers suspected of having pervasive developmental disorders. Autism 12, 627–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Ozonoff SJ, Ursu S, Ravizza S, Cummings N, Ly S, et al. , 2009. The neural substrates of cognitive control deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia 47, 2515–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Yoon JH, Ragland JD, Niendam TA, Lesh TA, Fairbrother W, et al. , 2014. The development of the neural substrates of cognitive control in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V, 2008. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 12569–12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Menon V, 2009. The anterior insula in autism: under-connected and under-examined. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 1198–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Amin H, Rykhlevskaia E, Nguyen DA, Greicius MD, et al. , 2010. Dissociable connectivity within human angular gyrus and intraparietal sulcus: evidence from functional and structural connectivity. Cereb. Cortex 20 (11), 2636–2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Lynch CJ, Khouzam A, Phillips J, Feinstein C, et al. , 2013. Salience network-based classification and prediction of symptom severity in children with autism. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 869–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers ME, Cohen MX, Geurts HM, 2012. Brain connectivity and high functioning autism: a promising path of research that needs refined models, methodological convergence, and stronger behavioral links. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 604–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von dem Hagen EA, Stoyanova RS, Baron-Cohen S, Calder AJ, 2013. Reduced functional connectivity within and between ‘social’ resting state networks in autism spectrum conditions. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8, 694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng SJ, Wiggins JL, Peltier SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C, et al. , 2010. Alterations of resting state functional connectivity in the default network in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 1313, 202–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins LD, Bakeman R, Adamson LB, Robins DL, 2016. The utility of the social communication questionnaire in screening for autism in children referred for early intervention. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 22, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins LD, Reynolds A, Rice CE, Moody EJ, Bernal P, Blaskey L, et al. , 2015. Using standardized diagnostic instruments to classify children with autism in the study to explore early development. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 1271–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Tong Y, Liu S, Chow HM, Abdul-Sabur NY, Mattay GS, et al. , 2014. Denoising the speaking brain: toward a robust technique for correcting artifact-contaminated fMRI data under severe motion. Neuroimage 103, 33–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang J, Fan L, Zhang Y, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, et al. , 2016. Functional organization of the fusiform gyrus revealed with connectivity profiles. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 3003–3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.