Abstract

Repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation is a noncanonical translation initiation event that occurs at nucleotide-repeat expansion mutations that are associated with several neurodegenerative diseases, including fragile X–associated tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), ALS, and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Translation of expanded repeats produces toxic proteins that accumulate in human brains and contribute to disease pathogenesis. Consequently, RAN translation constitutes a potentially important therapeutic target for managing multiple neurodegenerative disorders. Here, we adapted a previously developed RAN translation assay to a high-throughput format to screen 3,253 bioactive compounds for inhibition of RAN translation of expanded CGG repeats associated with FXTAS. We identified five diverse small molecules that dose-dependently inhibited CGG RAN translation, while relatively sparing canonical translation. All five compounds also inhibited RAN translation of expanded GGGGCC repeats associated with ALS and FTD. Using CD and native gel analyses, we found evidence that three of these compounds, BIX01294, CP-31398, and propidium iodide, bind directly to the repeat RNAs. These findings provide proof-of-principle supporting the development of selective small-molecule RAN translation inhibitors that act across multiple disease-causing repeats.

Keywords: translation, drug screening, neurodegeneration, RNA, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Lou Gehrig disease), small molecule, C9orf72, FXTAS, Lou Gehrig's disease, RAN translation

Introduction

Repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN)5 translation has recently emerged as a common pathogenic mechanism among nucleotide repeat expansion diseases. Through this process, the ribosome initiates translation upstream of or within stable secondary structures formed by repetitive RNA sequences, in the absence of an AUG start codon (1). This leads to production of RAN peptides, often aggregate-prone proteins with repetitive amino acid sequences resulting from translation of the repetitive RNA element.

To date, RAN translation is known to occur in at least nine different human diseases: fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) (2, 3), ALS (4–7), frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (4–7), spinocerebellar ataxia type 8 (1), myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2 (1, 8), Huntington's disease (9), fragile X–associated primary ovarian insufficiency syndrome (10), and Fuchs' endothelial corneal dystrophy (11). These diseases are caused by multiple different microsatellite repeat sequences located within various regions (e.g. coding sequence, UTRs, intron) of different genes.

FXTAS is a late-onset neurodegenerative disease characterized by difficulty walking, loss of fine motor skills, and progressive cognitive and behavioral changes (12) that affects up to 1 in 3,000 men over the age of 50 (13). FXTAS results from the expansion of CGG repeats within the 5′ leader of FMR1, from an average of 30 or fewer CGGs to 55–200 (14). RAN translation of this repeat in the +1 (GGC) reading frame generates a polyglycine protein, FMRPolyG, that is found within inclusions in patient neurons (2, 15, 16). When overexpressed from a CGG repeat in Drosophila or mice, FMRPolyG is neurotoxic, causing motor deficits, neurodegeneration, and reduced lifespans (2, 15).

ALS and FTD are also neurodegenerative diseases. ALS is the most common form of motor neuron disease, and FTD is the second most common form of early-onset dementia. The most common genetic cause of both ALS and FTD is an expansion of GGGGCC repeats within the first intron of C9ORF72 (17–19). RAN translation in all three reading frames of the expanded GGGGCC repeat produces three different dipeptide repeat proteins: glycine-alanine (GA; GGG-GCC), glycine-proline (GP; GGG-CCG), and glycine-arginine (GR; GGC-CGG). All three dipeptide repeat proteins are detected in patient neurons (4, 5, 7), and the GR product has repeatedly been shown to be highly toxic across model systems (20–22), with more moderate toxicity from the GA product also reported (20, 23–25).

Despite differences in repeat sequence and context, our laboratory and others have shown that RAN translation from reporter constructs with FXTAS-associated CGG repeats (CGG RAN) and C9ALS/FTD-associated GGGGCC repeats (C9RAN) share common mechanistic features (26–29). RAN translation in all three reading frames across both repeats occurs most efficiently when the ribosome is able to bind at the 5′ cap and scan in a 5′ to 3′ direction (26–29). Additionally, for both repeats, RAN translation in the reading frame that generates the most abundant RAN peptide in patient tissue (FMRPolyG and GA) (2, 30) predominantly utilizes a near-AUG codon upstream of the repeat for initiation (26–28, 31). However, evidence also suggests that initiation can occur, at lower levels, within the repeat sequence itself and in a cap-independent manner (1, 29, 31). Intriguingly, activation of the integrated stress response and phosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2α enhance RAN translation of both the CGG and GGGGCC repeats in model systems (27, 29, 31, 32)

To better define the mechanism of RAN translation and identify potential inhibitors of this process, we developed an in vitro, reporter-based small molecule screen for bioactive compounds that selectively and dose-dependently inhibit RAN translation of CGG repeats. From this screen, we identified five novel CGG RAN translation inhibitors and found that each compound also inhibits RAN translation of C9ALS/FTD-associated GGGGCC repeats, in multiple sense-strand reading frames. Using CD and native gel analysis, we show that three of these compounds bind the repeats and alter their secondary structure in a manner similar to previously developed small molecule inhibitors (33–35). These studies establish that RAN translation from multiple repeat expansions and across multiple reading frames can be selectively targeted by small-molecule inhibitors, providing insights into the mechanisms by which RAN translation occurs and establishing a framework for future therapeutic development in nucleotide repeat expansion disorders.

Results

Primary screen of 3,253 bioactive compounds for inhibitors of CGG RAN translation

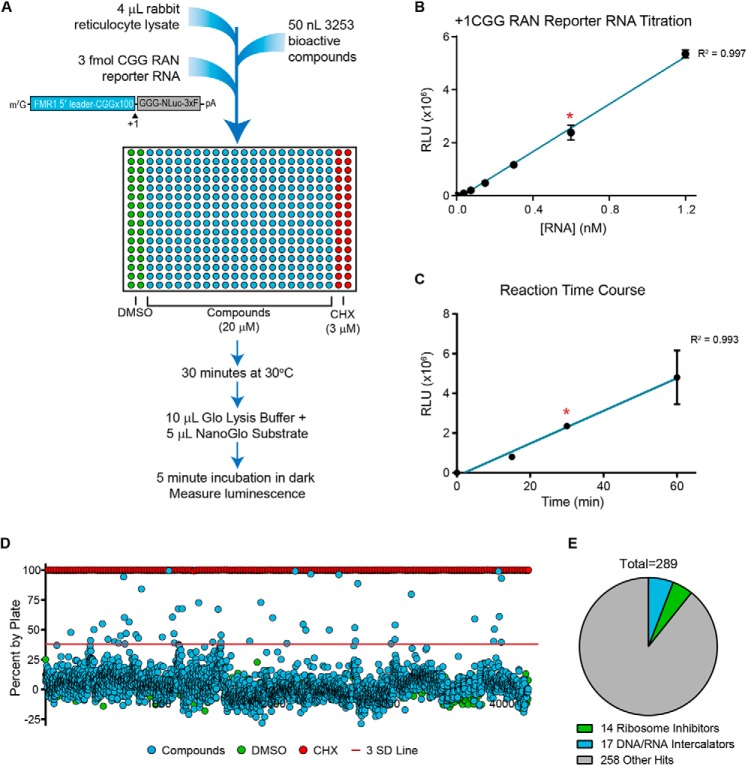

To identify small-molecule inhibitors of RAN translation of FXTAS-associated CGG repeats, we adapted a previously developed in vitro RAN translation assay (26) to a 384-well format (Fig. 1A). This assay utilized a +1CGGx100 RAN translation nanoluciferase (NLuc) reporter mRNA, which was added to wells containing rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) treated with one of 3,253 bioactive compounds at 20 μm (Fig. 1A). After a 30-min incubation at 30 °C, luminescence was measured as a readout for production of the neurotoxic polyglycine RAN protein (FMRpolyG) in each well (Fig. 1A). We confirmed that under these conditions, the reporter mRNA produced robust RAN-specific luminescent signal within the dynamic linear range of detection (Fig. 1 (B and C) and Fig. S1A).

Figure 1.

Screen of 3,253 bioactive compounds for inhibitors of RAN translation. A, schematic of primary screen design. In each plate, DMSO (columns 1 and 2) served as an internal negative control, and 3 μm cycloheximide (CHX; columns 23 and 24) served as an internal positive control for translation inhibition. Compounds screened were from the Pilot LOPAC, Pilot Prestwick, Pilot NCC-Focused, and Navigator Pathways libraries. 3xF, 3xFLAG tag. B, linear relationship between +1CGG RAN reporter mRNA concentration and luminescence for in vitro translation assay under conditions used for primary screen. C, linear relationship between reaction time and luminescence for in vitro translation assay with 3 fmol of +1CGG NLuc RAN reporter mRNA under conditions used for the primary screen. For B and C, teal lines represent linear regression fit, with a red asterisk indicating conditions used in the screen. Each point represents the mean of n = 3. Error bars, S.D. D, percentage change in NLuc signal for all 3,253 compounds relative to the DMSO vehicle controls. The red line approximately represents 3 S.D. values from vehicle controls. E, pie chart of screen hits, indicating the proportion of hits that are known ribosome inhibitors or DNA/RNA intercalators.

The 3,253 compounds screened with this assay came from the Pilot LOPAC, Pilot Prestwick, Pilot NCC-focused, and Navigator Pathways small-molecule libraries. These libraries contain pharmacologically active compounds, small molecules previously tested in clinical trials, and FDA-approved drugs, all in DMSO. As a positive control for translation inhibition, the last two columns of each plate were treated with 3 μm cycloheximide, and as an internal negative control, the first two columns were treated with DMSO (Fig. 1A). The average Z-factor and coefficient of variability value, calculated per plate, were 0.79 and 6.93%, respectively (Table 1), indicating that the screen was of high quality. This allowed us to identify 289 “hits,” which we defined as compounds that reduced +1CGG RAN translation by greater than 20% or 3 S.D. values relative to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 1D, Table 2, and Table S1). These hits had diverse structures and annotated biological targets. Whereas 14 known ribosomal inhibitors and 17 DNA/RNA intercalators were identified, the majority of hits represented other classes of compounds, acting through less obvious modes of translational inhibition (Fig. 1E).

Table 1.

Primary screen statistics

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Z′ scores per plate | |

| Average | 0.79 |

| Minimum | 0.70 |

| Maximum | 0.88 |

| Coefficients of variance per plate | |

| Average | 6.93% |

| Minimum | 3.88% |

| Maximum | 9.82% |

Table 2.

Summary of primary screen hits

| Signal reduction range | No. of compounds |

|---|---|

| 20–39% | 154 |

| 40–59% | 25 |

| 60–79% | 9 |

| 80–99% | 8 |

| >3 S.D. values below mean | 211 |

| Total (>20% or >3 S.D.) | 274 |

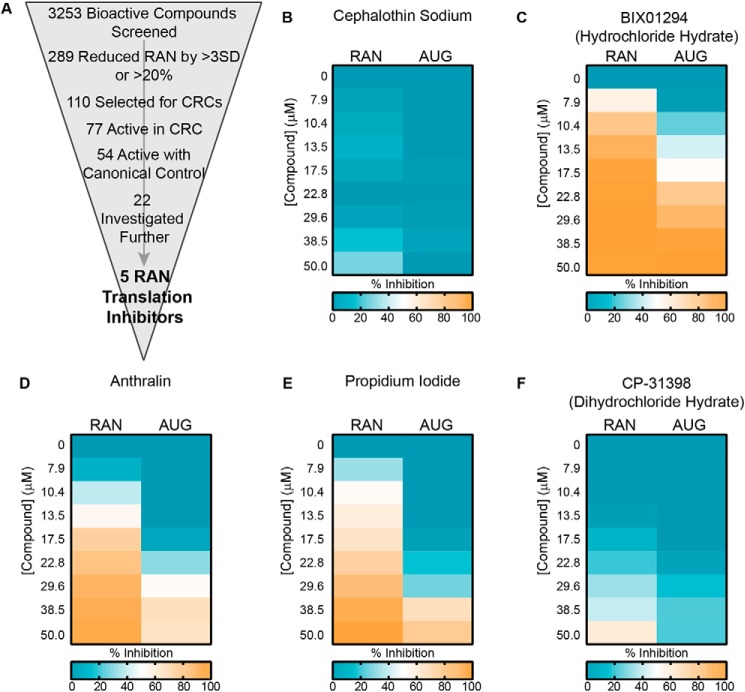

Concentration response and counterscreen

From 289 primary hits, we selected 110 inhibitors to advance to a secondary concentration-response curve analysis (Fig. 2A). Compounds were selected primarily based on their percentage inhibition and how many S.D. values their effect differed from vehicle-only controls. Preference was given to compounds that were FDA-approved or that were hits multiple times when present in multiple libraries. Compounds that were flagged for concerns about toxicity, active in greater than 90% of luciferase assays previously performed at our screening facility, or known translation inhibitors of a mechanism already represented among selected hits were excluded unless of particular interest. Additionally, an S.D. cut-off of 2.5 was applied to compounds added to wells at the edge of the plate, where signal was more variable.

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves and counterscreen. A, schematic of screen work flow, with the number of hits at each step indicated. CRC, concentration-response curve. B, representative heat map of a “RAN-specific inhibitor,” cephalothin, showing percentage inhibition of +1CGG RAN translation and canonical AUG translation at the indicated concentrations. C–F, representative heat maps of “RAN-selective inhibitors,” showing percentage inhibition of +1CGG RAN translation and canonical AUG translation at the indicated concentrations. For B–F, heat map values are the average of duplicate reactions. For visual clarity, effects of <0% inhibition (increases) were set to zero.

Selected compounds were added to the RRL at eight concentrations from 50 to 8 μm, in duplicate. To obtain a 50 μm dose, the volume of compound added to each well increased the final percentage of DMSO in the reaction mixture from 1% in the primary screen to 2%. We confirmed that at this level, DMSO did not significantly inhibit +1CGG RAN translation on its own (Fig. S2A). Of the 110 compounds selected, 77 exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of +1CGG RAN translation, whereas 33 did not (Fig. 2A and Table S2). Among the 33 compounds that failed to validate, only three reduced signal in the primary screen by both more than 20% and 4 S.D. values relative to controls (Table S2).

To eliminate compounds that nonspecifically inhibited all translation, with no specificity for RAN translation, the concentration-response curve assay was simultaneously performed with an NLuc reporter mRNA lacking any repeat element and translated using a canonical AUG start codon (AUG-NLuc) (Fig. S2, B and C). Of the 77 validated hits, 54 also inhibited translation of the AUG-initiated canonical reporter in a dose-dependent manner. Consequently, 23 compounds exclusively and dose-dependently inhibited +1CGG RAN translation and were called “RAN-specific inhibitors” (Fig. 2B and Table S2). None of these compounds were of high potency; the IC50 of the most potent, amlexanox, was 26.3 μm (Table S2). An additional 30 compounds were more potent inhibitors of +1CGG RAN translation than canonical translation (Fig. 2 (C–F) and Table S2). These were called “RAN-selective inhibitors.” As a group, the RAN-selective inhibitors were more potent than the RAN-specific inhibitors, with IC50 values ranging from 0.72 to 81.3 μm (Table S2).

Of the remaining 24 compounds that reduced both +1CGG RAN and AUG-NLuc translation, 16 had similar activity with both, whereas eight were more potent inhibitors of canonical translation (Table S2).

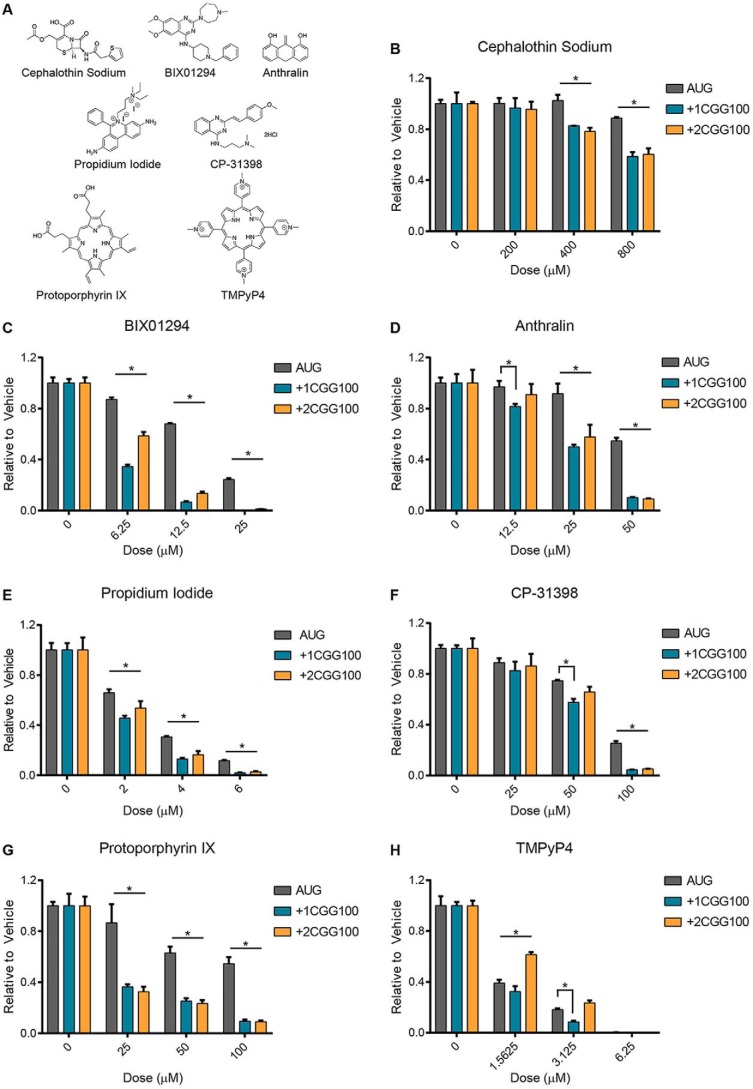

Five bioactive compounds selectively inhibit CGG RAN translation in multiple reading frames

Based on results from the concentration response and counterscreen, 22 compounds were selected for independent validation, including 13 RAN-specific and nine RAN-selective inhibitors (Fig. 2A and Table 3). Each compound was added at 4–5 doses to a 10-μl RRL in vitro translation assay using the same reporter mRNAs as in the primary screen and counterscreen. Of these compounds, only one RAN-specific and four RAN-selective inhibitors significantly and dose-dependently inhibited +1CGG RAN translation, while leaving translation of the canonical AUG-NLuc reporter relatively spared (Table 3). These compounds included cephalothin, a discontinued β-lactam antibiotic; BIX01294, a histone lysine methyltransferase inhibitor; anthralin, an FDA-approved drug used in topical treatments for psoriasis; propidium iodide, a fluorescent nucleic acid intercalating agent; and CP-31398, a p53 stabilizer (Fig. 3, A–F). As a group, these compounds have diverse biological targets and structures. However, interestingly, BIX01294 and CP-31398 share a similar functional group (Fig. 3A).

Table 3.

Activity of compounds in independent validation

| Compound name | ID no. | Active against +1CGGx100? | Active against AUG? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kenpaullone | CCG-35778 | No | No |

| BIX01294 (hydrochloride hydrate) | CCG-208677 | Yes | Less |

| Propidium iodide | CCG-220792 | Yes | Less |

| Amlexanox | CCG-100953 | No | No |

| Anthralin | CCG-38920 | Yes | Less |

| Rosiglitazone maleate | CCG-100943 | No | No |

| X80 | CCG-222138 | Yes | Yes |

| Balsalazide disodium | CCG-213078 | No | No |

| CP-31398 dihydrochloride hydrate | CGG-222578 | Yes | Less |

| Phenazopyridine hydrochloride | CGG-39935 | No | No |

| Rufloxacin hyrdochloride | CGG-100908 | No | No |

| Reserpine | CGG-204168 | No | No |

| Efavirenz | CGG-101011 | No | No |

| Alfuzosin hydrochloride | CGG-213373 | No | No |

| Cephalothin sodium | CCG-38923 | Yes | Less |

| Rofecoxib | CGG-40253 | No | No |

| Isoxicam | CCG-40307 | Yes | Yes |

| Pefloxacine mesylate | CCG-39994 | No | No |

| Parbendazole | CCG-221110 | No | No |

| Sulfamethazine sodium salt | CCG-220775 | No | No |

| Olanzapine | CCG-100922 | No | No |

| Oxiconazole nitrate | CCG-40020 | No | No |

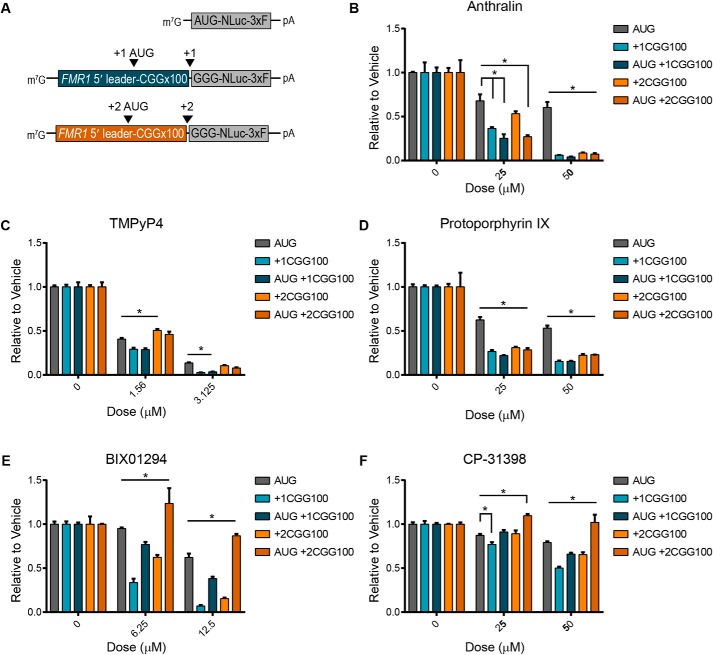

Figure 3.

Small molecules inhibit CGG RAN translation in multiple reading frames. A, structures of compounds used in B–H. B–F, compounds identified from screen as RAN translation inhibitors were independently reassessed for their activity in RRL in vitro translation assays. The indicated compounds were added at increasing doses to 30% RRL reactions with AUG, +1CGGx100, or +2CGGx100-NLuc reporter mRNAs, and luminescence was measured relative to vehicle (DMSO) treatment. G and H, candidate compounds protoporphyrin IX and TMPyP4 were added at increasing concentrations to RRL reactions with AUG, +1CGGx100, or +2CGGx100-NLuc reporter mRNAs. Luminescence was measured relative to vehicle (DMSO) treatment. For all graphs, n = 3; error bars, S.D. *, p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test.

The remaining 17 compounds either had no effect on RAN translation or also inhibited canonical translation to a similar degree during independent validation (Fig. S3 (A–D) and Table 3). To assess the possibility that results observed in the primary screen for these 17 compounds came from a by-product produced through extended storage durations, we incubated a subset at 37 °C for 1 week. However, this did not substantially affect their inhibitory properties (data not shown).

RAN translation of the expanded CGG repeat also occurs in the +2 reading frame (GCG), generating a polyalanine protein (FMRPolyA) (2). However, unlike initiation in the +1 reading frame, initiation in the +2 frame does not utilize a near-AUG codon and likely occurs within the repeat sequence itself (26). We were therefore interested to see whether the five inhibitors of +1CGG RAN translation also reduced +2CGG RAN translation. Cephalothin, BIX01294, anthralin, and CP-31398 all significantly inhibited translation from a +2CGGx100 RAN translation reporter mRNA (26), relative to the canonical AUG-NLuc control (Fig. 3, B–D and F). However, at the doses tested, propidium iodide did not (Fig. 3E). Consequently, RAN translation resulting in the synthesis of distinct polypeptides, from initiation at different codons in different reading frames, can be inhibited simultaneously by the same small molecule, although this effect cannot be generalized to all inhibitors.

We also assessed the inhibitory activity of two additional small molecules, protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) and TMPyP4. PPIX is a natural compound that consists of porphyrin ring. It is known to bind G-quadruplex structures and increases levels of FMRP in fragile-X patient cells (36). TMPyP4 is structurally similar to PPIX, also consisting of a porphyrin ring, and known to bind CGG and GGGGCC repeat RNA (37, 38). When tested, both compounds selectively inhibited CGG RAN translation, relative to the AUG-NLuc control (Fig. 3, G and H). However, unlike PPIX, TMPyP4 only had relative selectivity for CGG RAN translation in the +1, and not the +2, reading frame for the doses tested, much like what we observed with propidium iodide (Fig. 3H).

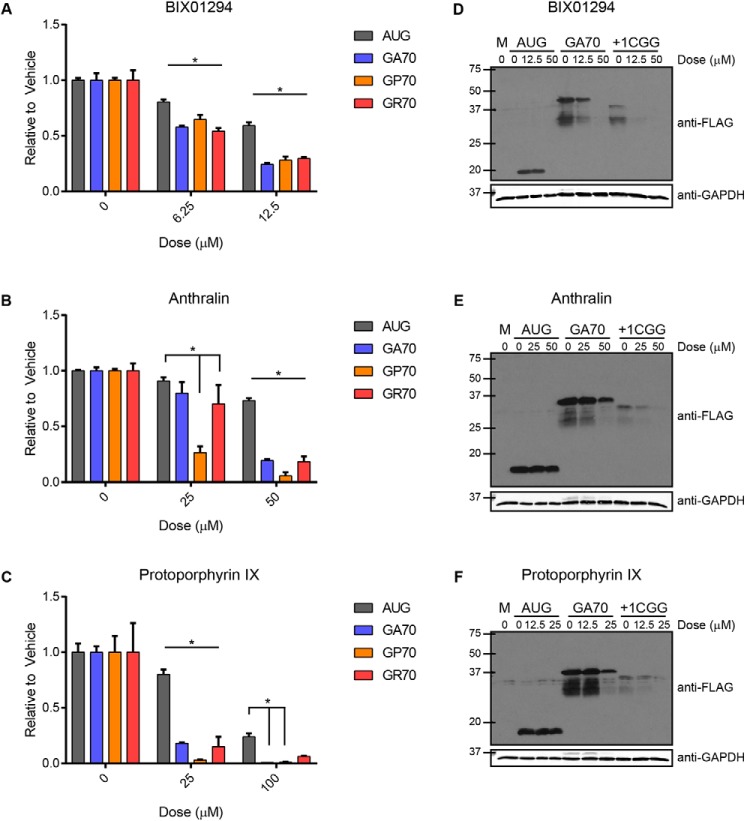

Inhibitors of CGG RAN translation also inhibit C9RAN translation

Recent work suggests mechanistic similarity between CGG RAN translation and C9ALS/FTD-associated GGGGCC RAN translation (C9RAN translation) (27–29). We therefore tested whether these small-molecule inhibitors of CGG RAN translation also impacted C9RAN translation. To accomplish this, we repeated the RRL in vitro translation assays using previously developed C9RAN translation-specific NLuc reporter mRNAs that contained 70 GGGGCC repeats (27). All five compounds identified in the CGG RAN translation screen, as well as PPIX, selectively and dose-dependently decreased C9RAN translation in multiple reading frames (GA, GP, and GR), relative to the AUG-NLuc control (Fig. 4 (A–C) and Fig. S4 (A–C)). We further confirmed that the decrease in luminescence from the CGG and C9RAN reporter mRNAs was due to a decrease in RAN polypeptide synthesis by Western blotting. BIX01294, anthralin, and PPIX all decreased poly-GA and FMRPolyG synthesis in RRL in a dose-dependent manner while leaving canonical NLuc synthesis relatively spared (Fig. 4, D–F).

Figure 4.

Small molecules inhibit C9RAN translation in all three reading frames. BIX01294 (A), anthralin (B), and protoporphyrin IX (C) were added at increasing concentrations to 30% RRL in vitro translation reactions with AUG-NLuc or GGGGCCx70 reporter mRNAs for all three reading frames, and luminescence was measured relative to vehicle (DMSO) control. D–F, selective inhibition of RAN translation of GGGGCCx70 and CGGx100 NLuc reporter mRNAs, relative to AUG-NLuc control, was confirmed by Western blotting against a C-terminal FLAG tag for the glycine-alanine (GA) and FMRPolyG (+1CGG) products, following incubation with BIX01294, anthralin, or protoporphyrin IX at the indicated doses. GAPDH was used as a loading control. For A–C, all graphs represent mean of n = 3; error bars, S.D. *, p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. M, mock; GA, glycine-alanine; GP, glycine-proline; GR, glycine-arginine.

Inhibitors target different aspects of RAN translation

To determine whether these small molecules inhibit RAN translation by targeting its non-AUG initiation, we repeated the in vitro translation reactions using reporters with AUG start codons inserted upstream of the expanded CGG repeats in either the +1 or +2 reading frames (26) (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5A). Anthralin, TMPyP4, and PPIX all inhibited AUG +1CGGx100 and AUG +2CGGx100 translation to a similar or greater extent than +1CGG and +2CGG RAN translation (Fig. 5, B–D). Consequently, the selectivity of these compounds for translation of expanded CGG repeats, relative to AUG-NLuc translation, was maintained regardless of whether repeat translation initiated with an AUG or non-AUG codon (Fig. 5, B–D). Conversely, BIX01294 and CP-31398 inhibition was markedly decreased when translation of the expanded repeats initiated with an AUG start codon (Fig. 5, E and F), indicating that their activity depends upon a non-AUG initiation event. Therefore, these five small molecules fall within two distinct groups that produce similar inhibitory effects by targeting different aspects of RAN translation.

Figure 5.

RAN translation inhibitors have varying effects on AUG-initiated repeat translation. A, schematic of NLuc reporter mRNAs used in 30% RRL in vitro translation assays, illustrating the position of the AUG start codons inserted upstream of the repeats, to drive translation in the indicated reading frames. The effect of anthralin (B), TMPyP4 (C), protoporphyrin IX (D), BIX01294 (E), and CP-31398 (F) on +1 and +2CGGx100 RAN translation, compared with AUG-initiated CGGx100 translation, measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of each small molecule. For B–F, values are relative to DMSO controls, and graphs represent the mean of n = 3. Error bars, S.D. *, p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. 3xF, 3xFLAG tag.

To assess whether the inhibitory activity of BIX01294 and CP-31398 on non-AUG-initiated translation was specific to mRNAs containing a repeat, we utilized two additional NLuc reporters: one that initiates at an ACG and the other at a CUG start codon (ACG-NLuc and CUG-NLuc), both lacking a repetitive element (39) (Fig. S5B). We specifically chose these two non-AUG start codons as they were previously shown to be used for FMRpolyG and poly-GA synthesis, respectively (26–28). Interestingly, relative to the canonical AUG-NLuc control, BIX01294 and CP-31398 more significantly inhibited translation from both the ACG-NLuc and CUG-NLuc reporters (Fig. S5, C and D). Therefore, a repeat is not required for translation inhibition by either compound. This supports the idea that non-AUG-initiated translation can be sufficiently distinct from canonical AUG-initiated translation to allow for selective targeting (40).

In contrast, anthralin, PPIX, and TMPyP4 all failed to inhibit translation of ACG-NLuc and CUG-NLuc reporter mRNAs, relative to the AUG-NLuc control (Fig. S5, E–G), indicating that their inhibitory effects are repeat-dependent. Furthermore, as expression of the near-AUG-initiated reporters is significantly lower than the AUG-initiated control (Fig. S5B), this suggests the relatively low expression of the repeat-containing reporters does not alone account for their selective inhibition by these compounds.

BIX01294 interacts with repeat RNAs

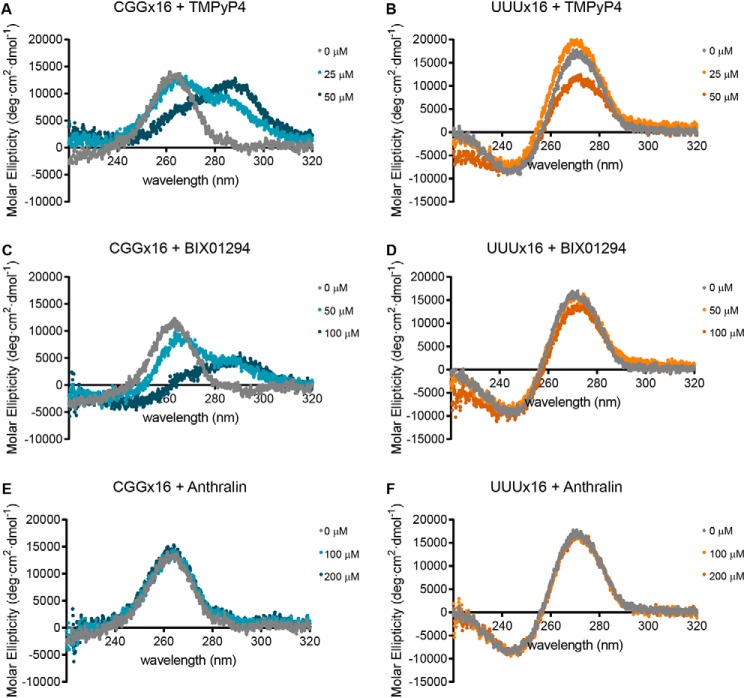

To test whether the RAN translation inhibitors directly interact with the repeat RNAs, as a possible mechanism for their inhibition, we utilized CD. First, we attained the CD spectrum of CGGx16 repeat RNA folded in the presence of 100 mm KCl (the concentration present in the RRL reactions) by heating to 95 °C and returning to room temperature. UUUx16 RNA, folded under the same conditions, was used as a control lacking both sequence and structural similarity. We then incubated each RNA with 25 and 50 μm TMPyP4, as a positive control for CGG repeat RNA binding. Consistent with previous findings (37, 41), TMPyP4 caused a dose-dependent shift in the CGGx16 RNA CD spectrum, whereas a higher dose of was required to alter UUUx16's CD spectrum (Fig. 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

CD analysis for small-molecule interactions with CGG repeat RNA. Molar ellipticity of 5 μm CGGx16 or UUUx16 RNA, measured between 320 and 220 nm with CD, following incubation with TMPyP4 (A and B), BIX01294 (C and D), or anthralin (E and F) at the indicated concentrations. All CD spectra were acquired at 25 °C, with 300-μl RNA samples folded in the presence of 100 mm KCl, and represent the average of six accumulations collected at 20 nm/min.

We next incubated the RNAs with increasing amounts of BIX01294 and anthralin. At both 50 and 100 μm, BIX01294 shifted CGGx16's CD spectrum but had little effect on UUUx16's (Fig. 6, C and D). Conversely, incubation with 100 or 200 μm anthralin had no effect on the CD spectra of either CGGx16 or UUUx16. Higher doses of anthralin were not tested by CD, as increasing concentrations of DMSO interfered with the absorbance spectra.

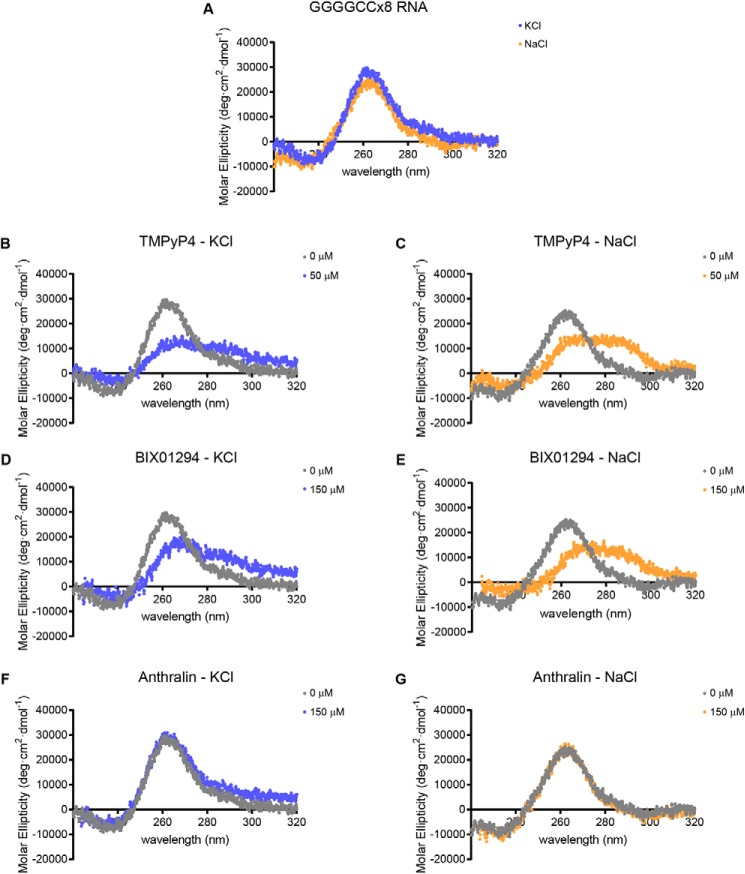

To determine whether these compounds interact similarly with the C9ORF72-associated GGGGCC repeat, we performed CD using a GGGGCCx8 repeat RNA. This RNA was folded at room temperature following heating to 95 °C in the presence of either 100 mm KCl, to promote the formation of a G-quadruplex structure, or in the presence of 100 mm NaCl, to promote hairpin formation (33, 38). Regardless of the cation used, TMPyP4 and BIX01294 shifted the GGGGCCx8 RNA CD spectra, whereas anthralin did not (Fig. 7), mirroring their interactions with the CGGx16 RNA.

Figure 7.

Interaction of small-molecule RAN translation inhibitors with GGGGCC repeat RNA by CD. A, comparison of the molar ellipticity of 2.5 μm GGGGCCx8 RNA, measured between 320 and 220 nm with CD, following folding in the presence of 100 mm KCl (blue) or 100 mm NaCl (orange). B–G, CD spectra of GGGGCCx8 RNA folded in the presence of either 100 mm KCl (blue) or 100 mm NaCl (orange), following incubation with the indicated concentrations of TMPyP4 (B and C), BIX01294 (D and E), or anthralin (F and G). All CD spectra were acquired at 25 °C, with 250-μl RNA samples and represent the average of six accumulations collected at 20 nm/min. The untreated RNA spectra in A are used for comparison with the RNA + compound spectra in B–G.

As a secondary measure of compound interaction with CGG repeat RNA, we utilized native gel electrophoresis to assay for an electrophoretic shift indicative of changes in the RNA structure due to compound binding. For this, we used 5′ IRdye 800CW-labeled CGGx16 and UUUx16 RNAs folded in the presence of 100 mm KCl. A 50 nm concentration of each RNA was incubated with increasing concentrations of each inhibitor and run on a 12% native polyacrylamide gel. The labeled RNAs were then visualized at 800 nm.

TMPyP4 was again used as a positive control for direct binding to the CGG repeat RNA (37). Increasing concentration of TMPyP4 led to a dose-dependent decrease in CGGx16's band intensity, despite equal RNA loading (Fig. S6A). This differs from a previous report using a radiolabeled CGG RNA with extensive sequence 5′ to the repeat (41) and may be the result of TMPyP4 binding interfering with detection of the RNA's IRdye. A similar result was obtained when TMPyP4 was incubated with the UUUx16 RNA (Fig. S6A).

BIX01294, propidium iodide, and CP-31398 all had a similar effect on the CGGx16 RNA as TMPyP4, causing a dose-dependent decrease in band intensity (Fig. 6, B–D). Additionally, they showed a preferential effect, as lower doses of each compound were required to reduce the intensity of the CGGx16 band relative to those needed to reduce intensity of the UUUx16 band (Fig. S6, B–D). However, only incubation with increasing concentrations of CP-31398 resulted in a clear upshift indicative of altered RNA secondary structure (Fig. S6D).

PPIX also modestly but preferentially decreased the CGGx16 RNA band intensity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S6E), whereas anthralin and cephalothin showed little evidence of interacting with either CGGx16 or UUUx16 RNA, even at excessively high doses (Fig. S6, F and G).

Therefore, by CD and/or native gel analysis, BIX01294 and CP-31398 exhibit preferential interaction with CG-rich repeats RNAs. Native gel results suggest a possible interaction between propidium iodide and CGGx16 RNA, whereas anthralin and cephalothin show no evidence of interaction. This may indicate that these sets of compounds utilize different mechanisms for inhibiting CGG RAN translation.

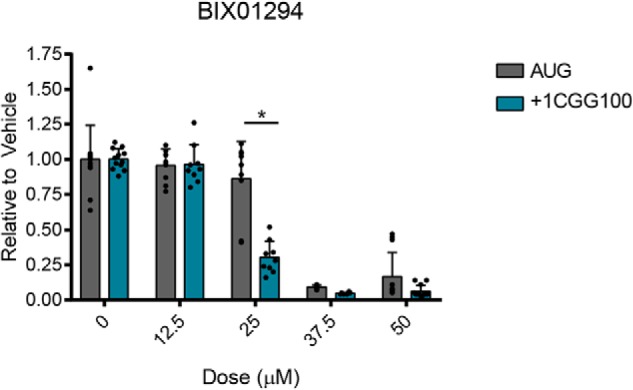

BIX01294 inhibits CGG RAN in cultured cells but is toxic

We next asked whether these small-molecule inhibitors of RAN translation were active in cultured cells. To do so, we applied BIX01294 to HEK293 cells transfected with plasmids expressing either AUG-NLuc, +1CGGx100-NLuc, or GA70-NLuc reporters. As an internal control for transfection efficiency and overall cellular health, all wells were co-transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter. 24 h post-treatment, luciferase activity was measured as a readout for translation of each reporter.

Relative to vehicle-treated controls, 25 μm BIX01294 significantly reduced +1CGG RAN translation, without affecting AUG-NLuc expression (Fig. 8). However, as assessed by changes in cellular morphology (data not shown) and a reduction in firefly luciferase signal (Fig. S7A), BIX01294 treatment at this dose was moderately toxic to cells. At doses above 25 μm, BIX01294 caused cellular death, with complete cellular detachment from plates (data not shown) and loss of firefly luciferase expression (Fig. S7A). In contrast, 25 μm BIX01294 treatment unexpectedly increased poly-GA expression (Fig. S7B), perhaps indirectly through changes in gene expression related to its primary biological activity as a histone lysine methyltransferase inhibitor.

Figure 8.

Effect of BIX01294 on +1CGG RAN translation in HEK293 cells. NLuc levels from HEK293 cells transfected with AUG-NLuc or +1CGGx100-NLuc–expressing plasmids and treated with BIX01294 at the indicated doses for 24 h. Luminescence values are expressed relative to DMSO-treated cells (0 μm). Graphs represent mean ± S.D., with each n represented by a dot. n = 12 for 0 and 50 μm doses, n = 9 for 12.5 and 25 μm doses, and n = 6 for 37.5 μm, from 2–4 independent experiments with n = 3 each. *, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple-comparison test.

We also applied BIX01294, anthralin, propidium iodide, and PPIX to primary rodent neurons at 1 μm and tracked the survival of these neurons over the course of 10 days using automated longitudinal fluorescence microscopy. Even at a dose well below the small molecules' in vitro IC50 values (Fig. 3), treatment with each increased the neurons' cumulative risk of death (Fig. S7C). Consequently, none of these small molecules are likely to represent good therapeutic candidates.

Discussion

In recent years, an emerging body of research has shown RAN translation to be a common factor in numerous repeat-expansion diseases. Although much work has established that RAN peptides are sufficient to cause neurotoxicity in a broad range of disease models, our understanding of the mechanisms of RAN translation, as well as how to selectively target it, is still incomplete.

Here we used an in vitro RAN translation reporter assay to perform a screen of bioactive compounds and identified five novel small-molecule inhibitors of this noncanonical translation event. Although none of these compounds are bioavailable, by interrogating their activity, they have revealed new insights into the mechanism of RAN translation.

We performed the initial screens using only a +1CGGx100 RAN reporter mRNA. However, each compound identified in the screen had similar activity against GGGGCCx70 RAN translation reporter mRNAs. Therefore, despite being different repeats, located within different sequence contexts, that produce different RAN peptide products, this finding supports mechanistic overlap between these translation events and suggests that future strategies to modify RAN translation in one disease could be more broadly applicable to the growing class of diseases associated with this event.

Previous studies to develop inhibitors of RAN translation have specifically focused on identifying small molecules that bind to the repeat RNAs (33–35, 42). For instance, compound 1a was identified based on its ability to bind to loops produced by the unpaired G-G nucleotides in the hairpin stem structures formed by both CGG and GGGGCC repeats (35). Subsequent studies established that 1a and structurally similar compounds reduce RAN translation of both RNAs in cultured cells, including C9ORF72 patient–derived iNeurons (33, 42). Additionally, a recent screen for molecules that bind G-quadruplexes successfully identified two such molecules that reduced C9RAN translation in GGGGCCx36-expressing Drosophila and C9ORF72 patient–derived motor neurons (34).

Consequently, small-molecule binding to repeat RNAs has proven to be a successful strategy at inhibiting RAN translation. This is consistent with the findings we report here, as three of the small-molecule inhibitors we identified in the screen, BIX01294, CP-31398, and propidium iodide, show evidence of interacting with CGG and/or GGGGCC repeat RNAs by CD and/or native gel analysis. Future work to determine whether the functional group shared by BIX01294 and CP-31398 is important for their interaction with the repeat RNAs and/or selective inhibition of RAN translation could provide insight into strategies for optimizing this effect. However, at higher doses, these compounds also interacted with the control UUUx16 RNA. Therefore, we have not excluded the possibility that interactions of these compounds with other RNAs or proteins in our translation system, such as ribosomal RNAs, contribute to their relatively selective inhibition of RAN translation.

Unlike in previous studies, by using a luciferase-based RAN translation reporter assay to directly measure RAN translation, we were able to unbiasedly screen a diverse library of bioactive compounds and potentially identify small molecules that inhibit RAN translation through novel mechanisms not related to repeat RNA binding. In this context, our finding that neither anthralin nor cephalothin directly interact with the CGG and/or GGGGCC repeat RNAs, as measured by CD or native gel analysis, is quite intriguing. This suggests that these compounds inhibit RAN translation through novel means, potentially by interacting with or inhibiting non-RNA-based factors that are selectively required for RAN translation.

Our findings also suggest that relatively selective inhibition of RAN translation can occur by targeting different aspects of the translation process. Relative to +1 and +2CGGx100 RAN translation, anthralin, TMPyP4, and PPIX inhibited AUG-initiated repeat translation to a similar or greater extent. This indicates that these compounds do not target the non-AUG initiation event of CGG RAN translation but may instead impair translation elongation through the repetitive RNA elements. Alternatively, BIX01294 and CP-31398 do specifically target the non-AUG initiation event; they were less effective at inhibiting AUG-initiated repeat translation compared with RAN translation and selectively inhibited translation from CUG-NLuc and ACG-NLuc reporters relative to an AUG-NLuc control.

In conclusion, this study serves as a proof-of-principle that small, bioactive compounds can selectively inhibit RAN translation across multiple disease-causing repeat expansion mutations. It has also revealed new lead compounds that could be used in future work to identify novel, targetable binding pockets in the repeat RNAs as well as new factors involved in RAN translation.

Experimental procedures

Reporter RNA in vitro transcription

pcDNA3.1(+) NLuc reporter plasmids (26, 27, 36, 39) were linearized with PspOMI. Capped and polyadenylated mRNAs were synthesized as described previously, using the HiScribe T7 high-yield RNA synthesis kit (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. E2040S), 3′-O-Me-m7GpppG anti-reverse cap analog (ARCA) (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. S1411S), RNase-free DNase I (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. M0303S), and Escherichia coli poly-A polymerase (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. M0276S) (26). Following synthesis, mRNAs were purified with RNA Clean and the Concentrator-25 kit from Zymo Research (catalogue no. R1017). The integrity and size of all in vitro transcribed mRNAs was verified on a denaturing formaldehyde RNA gel. The sequence of reporters are included in Table S3.

Primary and secondary screens

RRL in vitro translation reactions were performed in white, flat bottom, polypropylene 384-well plates from Greiner (catalogue no. 784075). RRL reaction mixture was prepared using Promega's Flexi System (catalogue no. L4540) and consisted of 30% RRL, 10 μm minus leucine amino acid mix, 10 μm minus methionine amino acid mix, 0.5 mm magnesium acetate, 100 mm potassium chloride, 4 units of murine RNase inhibitor (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. M0314L), and 0.05% Tween 20. The addition of Tween 20 was necessary to minimize adhesion of the reaction mixture to the multidrop tubing and even dispensing between wells and did not alter the levels of translation from the +1 CGG RAN or AUG-NLuc reporter RNAs (Fig. S1B). 4 μl of RRL mixture was dispensed per well using Thermo Labsystems multidrop plate dispenser at medium speed. 50 nl of DMSO was then multidropped into columns 1 and 2, and 50 nl of cycloheximide was added to columns 23 and 24, for a final concentration of 3 μm. To the remaining wells, 50 nl of 3,253 compounds, at 2 mm, from the Pilot LOPAC, Pilot Prestwick, Pilot NCC Focused, and Navigator pathway libraries were pintooled using a Sciclone ALH 300 advanced liquid handling system, for a final concentration of 20 μm. 1 μl (3 fmol of +1 CGG RAN, 1 fmol of AUG-NLuc) in vitro transcribed reporter RNA was then multidropped into each well.

Plates were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. Translation reactions were then terminated by the addition of 50 nl of 10 μm cycloheximide to each well, using a multidrop dispenser. 10 μl of room temperature Glo Lysis Buffer (Promega, catalogue no. E2661) was dispensed into each well with the multidrop, at low speed, which was essential for maintaining the stability of NLuc luminescence. To this, 5 μl of room temperature NanoGlo Substrate diluted 1:50 in NanoGlo Buffer (Promega, catalogue no. N1120) was dispensed via multidrop at low speed. Plates were then covered, mixed gently, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Luminescence was measured with a PerkinElmer EnVision plate reader.

The concentration-response curve and counterscreen were performed using all of the same reagents, materials, and equipment as in the primary screen. The only difference was that selected compounds were added to 384-well plates at eight doses from 50 to 8 μm, in duplicate, using TTP Labtech Mosquito X1 Hit-Picking Liquid Handler, prior to the addition of RRL.

After measuring luminescence, pIC50 values were calculated through the University of Michigan's Center for Chemical Genomics' MScreen software, using a four-parameter logistic equation (43). Initial minimum limits for curve fits were informed by the minimum value of each plate, determined by the cycloheximide-treated internal positive controls. Regression analysis then derived a curve fit, with a calculated minimum and maximum limit, for each compound. IC50 values greater than the maximum dose in the assay (50 μm) were extrapolated from the curve fit.

Independent validation of hits in RRL system

The following compounds were purchased through Sigma Marketsite: cephalothin sodium (Sigma–Aldrich, C4520), rufloxacin HCl (Vitas-M Laboratory, Ltd., STK711124), rofecoxib (Sigma–Aldrich, MFCD00935806), alfuzosin HCl (Sigma–Aldrich, A0232), olanzapine (Sigma–Aldrich, O1141), protoporphyrin IX (Chem-Impex Int, Inc., 21661), pefloxacine mesylate (Selleck Chemicals, S1855), reserpine (Sigma–Aldrich, MFCD00005091), isoxicam (Sigma–Aldrich, MFCD000079374), phenazopyridine HCl (Sigma–Aldrich, MFCD00035347), parbendazole (Sigma–Aldrich, MFCD018910864), balsalazide disodium salt dihydrate (Key Organics/BIONET, KS-5216), efavirenz (Sigma–Aldrich, SML0536), oxiconazole nitrate (Key Organics/BIONET, KS-5288), sulfamethazine sodium salt (Sigma, S5637-25G), kenpaullone (Adooq Bioscience, A11220), propidium iodide (Sigma, P4170), BIX01294 HCl hydrate (Cayman Chemical, 13124), anthralin (Key Organics/BIONET, KS-5183), CP-31398 dihydrochloride hydrate (Tocris Bioscience, 3023), X80 (Sigma, X3629), amlexanox (Sigma, 68302-57-8).

Compounds were all dissolved to 10–100 mm stocks in DMSO and stored in single-use aliquots at −20 °C. For in vitro translation assays, compounds were diluted in DMSO and added to RRL for a final DMSO concentration of 1% of total reaction volume. mRNAs were in vitro translated with the Flexi Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate System from Promega, as performed for the primary screen, with a few slight modifications. First, 0.05% Tween 20 was excluded from reactions, as regular pipetting eliminated the need to prevent RRL adhesion to multidrop dispenser tubing. Additionally, the reaction volume was increased to 10 μl, with an RNA concentration of 0.6 nm. Incubations were performed in polypropylene PCR tubes, and reactions were terminated on ice and then transferred to black 96-well plates. Samples were diluted 1:7 in Glo Lysis Buffer (Promega) prior to 5 min incubation in the dark with NanoGlo Substrate freshly diluted 1:50 in NanoGlo Buffer (Promega). Luminescence was measured on a GloMax 96 microplate luminometer.

Reactions for Western blotting assays were performed as above, except 50 ng of mRNA was used, as described previously (27). Membranes were probed with the following antibodies: 1:1,000 FLAG-M2 (mouse; Sigma, F1804), 1:1,000 GAPDH 6C5 (mouse; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., sc32233).

Circular dichroism

CGGx16, UUUx16, and GGGGCCx8 RNAs were purchased from IDT, with RNase-free HPLC purification.

CGGx16 and UUUx16 RNAs were diluted to 5 μm in 300 μl of RNA-folding buffer consisting of 100 mm KCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, and 0.1 mm EDTA (38). GGGGCCx8 RNA was diluted to 2.5 μm in 250 μl of RNA-folding buffer, consisting of either 100 mm KCl or 100 mm NaCl with 10 mm Tris-HCl and 0.1 mm EDTA. Diluted RNAs were heated to 95 °C for 1 min and cooled to room temperature.

CD was performed using a Jasco J-1500 circular dichroism spectrophotometer. Sample were scanned from 320 to 220 nm at 25 °C (38). Spectra were collected with scanning speed of 20 nm/min (38), data interval of 0.1 nm, response time of 1 s and 1 nm bandwidth. Spectra are the average of six accumulations, and only data with a heat tension less than 500 is shown. Increasing volumes of compounds were progressively added to the same RNA sample, to obtain increasing doses. The resulting decrease in RNA concentration due to increasing volume was accounted for in the molar ellipticity calculations. Spectra collected on the same day were compared with the same untreated RNA spectra, for each RNA and cation tested. All spectra were corrected for the background, by subtracting the buffer spectra using Jasco software, and baselined by setting the first value of the RNA-only spectra to zero.

Native gel analysis

5′ IRDye-800CW–modified CGGx16 and UUUx16 RNAs were purchased from IDT, with RNase-free HPLC purification. RNAs was diluted to 50 nm in buffer containing 100 mm KCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, and 0.1 mm EDTA, heated to 95 °C for 1 min, and cooled to room temperature.

Folded RNAs were then incubated with the indicated compounds and at the indicated doses for 30 min at room temperature. 4 μl of Orange-G loading dye (40% glycerol, 0.1% Orange-G, 1× TBE, and sterile MQ H2O) was added to each reaction, and entire reactions were loaded into 12% native polyacrylamide gels (12% acrylamide:bisacrylamide, 29:1, 1× TBE, 0.1% ammonium persulfate, TEMED, and sterile MQ H2O), with 4% stacks. Prior to loading, gels were prerun in 1× TBE at 100 V for ∼45 min. Samples were run on ice at 70 V for ∼95 min, and entire gels within glass cartridges were imaged with LI-COR Odyssey CLx Imaging System.

Compound activity in HEK293 cells

HEK293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573) were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in 10-cm dishes containing 10 ml of DMEM + high glucose (GE Healthcare Bio-Science, SH30022FS) supplemented with 9.09% fetal bovine serum (50 ml added to 500 ml of DMEM; Bio-Techne, S11150). 100 μl of cells were plated at 2.2 × 105 cells/ml in 96-well plates (Fisher, FB012931). Approximately 24 h post-plating, at 50–60% confluence, cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1+ NLuc reporter plasmids and control pGL4.13 firefly luciferase plasmid (26, 27). 50 ng of each plasmid was transfected per well, using FuGene HD (Promega, E2312) at a 3:1 ratio of reagent to total DNA, according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Approximately 24 h post-transfection, at ∼90% confluence, cells were treated with BIX01294 at the indicated doses. 24 h post-treatment, cells were lysed in 60 μl of Glo Lysis Buffer per well, for 5 min at room temperature with rocking. In opaque, black 96-well plates (Grenier Bio-One, 655076), 25 μl of lysate was then separately incubated for 5 min in the dark at room temperature with 25 μl of NanoGlo Substrate freshly diluted 1:50 in NanoGlo Buffer or 25 μl of ONE-Glo Buffer (Promega, E6110). NLuc and firefly luminescence were measured on a GloMax 96 microplate luminometer.

Primary neuron survival experiments

Primary cortical neurons from embryonic day 19–20 rats were harvested and cultured at 0.6 × 106 cells/ml in 96-well cell culture plates, as described previously (44, 45). Neurons were cultured in NEUMO photostable medium containing SOS supplement (Cell Guidance Systems) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Primary neurons were co-transfected with 0.1 μg of the survival marker, pGW1-mApple, and 0.1 μg of pGW1-EGFP on day 4 in vitro using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). 24 h post-transfection, compounds or DMSO were added to neurons, immediately following the first imaging run. Images were taken for 10 consecutive days with an automated fluorescent microscopy platform, as described previously (44–47). Image processing and survival analysis were acquired for each neuron at each time point using custom code written in Python or the ImageJ macro language. For survival analyses, differences among populations through Cox proportional hazards analysis were determined with the publicly available R survival package.

Author contributions

K. M. G., M. G. K., and P. K. T. conceptualization; K. M. G. data curation; K. M. G., S. J. B., and P. K. T. formal analysis; K. M. G., U. J. S., B. N. F., S. E. W., A. B. S., and S. J. B. investigation; K. M. G., B. N. F., A. B. S., M. G. K., S. J. B., M. I. I., and P. K. T. methodology; K. M. G. and P. K. T. writing-original draft; K. M. G., B. N. F., S. E. W., M. G. K., S. J. B., M. I. I., and P. K. T. writing-review and editing; U. J. S. validation; M. G. K., M. I. I., and P. K. T. supervision; P. K. T. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicholas Santoro, Tom McQuade, Renju Jacob, and Martha Larsen (Center for Chemical Genomics, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan) for help with the compound library screen, data mining, and MScreen software use. We also thank Veronica Towianski for technical assistance during the independent validation of compound hits, Luke Parks and the University of Michigan's Biophysics Department for invaluable training and assistance with the CD experiments, Sarah Cox for assistance with the CD software, and ChemDraw, Fang He, and all members of the Todd laboratory for feedback on this project and manuscript.

This work was supported by Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Grants 1I21BX001841 and 1I01BX003231, National Institutes of Health Grants R01NS099280 and R01NS086810, and the Michigan Alzheimer's Disease Center and Protein Folding Disease Initiative (to P. K. T., M. I. I., and A. B. S.). P. K. T. served as a consultant with Denali Therapeutics, and he, K. M. G., and M. G. K. licensed technology through the University of Michigan to Denali Therapeutics that is based on the work published here. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S7.

- RAN

- repeat-associated non-AUG

- TBE

- Tris borate-EDTA

- TEMED

- N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine

- FXTAS

- fragile X–associated tremor ataxia syndrome

- RRL

- rabbit reticulocyte lysate

- NLuc

- nanoluciferase

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- PPIX

- protoporphyrin IX

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

References

- 1. Zu T., Gibbens B., Doty N. S., Gomes-Pereira M., Huguet A., Stone M. D., Margolis J., Peterson M., Markowski T. W., Ingram M. A., Nan Z., Forster C., Low W. C., Schoser B., Somia N. V., et al. (2011) Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 260–265 10.1073/pnas.1013343108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Todd P. K., Oh S. Y., Krans A., He F., Sellier C., Frazer M., Renoux A. J., Chen K. C., Scaglione K. M., Basrur V., Elenitoba-Johnson K., Vonsattel J. P., Louis E. D., Sutton M. A., Taylor J. P., et al. (2013) CGG repeat-associated translation mediates neurodegeneration in fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. Neuron 78, 440–455 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krans A., Kearse M. G., and Todd P. K. (2016) Repeat-associated non-AUG translation from antisense CCG repeats in fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome. Ann. Neurol 80, 871–881 10.1002/ana.24800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ash P. E., Bieniek K. F., Gendron T. F., Caulfield T., Lin W. L., Dejesus-Hernandez M., van Blitterswijk M. M., Jansen-West K., Paul J. W. 3rd, Rademakers R., Boylan K. B., Dickson D. W., and Petrucelli L. (2013) Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 77, 639–646 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mori K., Weng S. M., Arzberger T., May S., Rentzsch K., Kremmer E., Schmid B., Kretzschmar H. A., Cruts M., Van Broeckhoven C., Haass C., and Edbauer D. (2013) The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 339, 1335–1338 10.1126/science.1232927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mori K., Arzberger T., Grässer F. A., Gijselinck I., May S., Rentzsch K., Weng S. M., Schludi M. H., van der Zee J., Cruts M., Van Broeckhoven C., Kremmer E., Kretzschmar H. A., Haass C., and Edbauer D. (2013) Bidirectional transcripts of the expanded C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat are translated into aggregating dipeptide repeat proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 881–893 10.1007/s00401-013-1189-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zu T., Liu Y., Bañez-Coronel M., Reid T., Pletnikova O., Lewis J., Miller T. M., Harms M. B., Falchook A. E., Subramony S. H., Ostrow L. W., Rothstein J. D., Troncoso J. C., and Ranum L. P. (2013) RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E4968–E4977 10.1073/pnas.1315438110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zu T., Cleary J. D., Liu Y., Bañez-Coronel M., Bubenik J. L., Ayhan F., Ashizawa T., Xia G., Clark H. B., Yachnis A. T., Swanson M. S., and Ranum L. P. W. (2017) RAN translation regulated by muscleblind proteins in myotonic dystrophy type 2. Neuron 95, 1292–1305.e5 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bañez-Coronel M., Ayhan F., Tarabochia A. D., Zu T., Perez B. A., Tusi S. K., Pletnikova O., Borchelt D. R., Ross C. A., Margolis R. L., Yachnis A. T., Troncoso J. C., and Ranum L. P. (2015) RAN translation in Huntington disease. Neuron 88, 667–677 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buijsen R. A., Visser J. A., Kramer P., Severijnen E. A., Gearing M., Charlet-Berguerand N., Sherman S. L., Berman R. F., Willemsen R., and Hukema R. K. (2016) Presence of inclusions positive for polyglycine containing protein, FMRpolyG, indicates that repeat-associated non-AUG translation plays a role in fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 31, 158–168 10.1093/humrep/dev280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soragni E., Petrosyan L., Rinkoski T. A., Wieben E. D., Baratz K. H., Fautsch M. P., and Gottesfeld J. M. (2018) Repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation in Fuchs' endothelial corneal dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 1888–1896 10.1167/iovs.17-23265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jacquemont S., Hagerman R. J., Leehey M., Grigsby J., Zhang L., Brunberg J. A., Greco C., Des Portes V., Jardini T., Levine R., Berry-Kravis E., Brown W. T., Schaeffer S., Kissel J., Tassone F., and Hagerman P. J. (2003) Fragile X premutation tremor/ataxia syndrome: molecular, clinical, and neuroimaging correlates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 869–878 10.1086/374321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacquemont S., Hagerman R. J., Leehey M. A., Hall D. A., Levine R. A., Brunberg J. A., Zhang L., Jardini T., Gane L. W., Harris S. W., Herman K., Grigsby J., Greco C. M., Berry-Kravis E., Tassone F., and Hagerman P. J. (2004) Penetrance of the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome in a premutation carrier population. JAMA 291, 460–469 10.1001/jama.291.4.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagerman R. J., Leehey M., Heinrichs W., Tassone F., Wilson R., Hills J., Grigsby J., Gage B., and Hagerman P. J. (2001) Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology 57, 127–130 10.1212/WNL.57.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sellier C., Buijsen R. A. M., He F., Natla S., Jung L., Tropel P., Gaucherot A., Jacobs H., Meziane H., Vincent A., Champy M. F., Sorg T., Pavlovic G., Wattenhofer-Donze M., Birling M. C., et al. (2017) Translation of expanded CGG repeats into FMRpolyG is pathogenic and may contribute to fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. Neuron 93, 331–347 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buijsen R. A., Sellier C., Severijnen L. A., Oulad-Abdelghani M., Verhagen R. F., Berman R. F., Charlet-Berguerand N., Willemsen R., and Hukema R. K. (2014) FMRpolyG-positive inclusions in CNS and non-CNS organs of a fragile X premutation carrier with fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2, 162 10.1186/s40478-014-0162-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeJesus-Hernandez M., Mackenzie I. R., Boeve B. F., Boxer A. L., Baker M., Rutherford N. J., Nicholson A. M., Finch N. A., Flynn H., Adamson J., Kouri N., Wojtas A., Sengdy P., Hsiung G. Y., Karydas A., et al. (2011) Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Renton A. E., Majounie E., Waite A., Simón-Sánchez J., Rollinson S., Gibbs J. R., Schymick J. C., Laaksovirta H., van Swieten J. C., Myllykangas L., Kalimo H., Paetau A., Abramzon Y., Remes A. M., Kaganovich A., et al. (2011) A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sareen D., O'Rourke J. G., Meera P., Muhammad A. K., Grant S., Simpkinson M., Bell S., Carmona S., Ornelas L., Sahabian A., Gendron T., Petrucelli L., Baughn M., Ravits J., Harms M. B., et al. (2013) Targeting RNA foci in iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients with a C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 208ra149 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mizielinska S., Grönke S., Niccoli T., Ridler C. E., Clayton E. L., Devoy A., Moens T., Norona F. E., Woollacott I. O. C., Pietrzyk J., Cleverley K., Nicoll A. J., Pickering-Brown S., Dols J., Cabecinha M., et al. (2014) C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science 345, 1192–1194 10.1126/science.1256800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wen X., Tan W., Westergard T., Krishnamurthy K., Markandaiah S. S., Shi Y., Lin S., Shneider N. A., Monaghan J., Pandey U. B., Pasinelli P., Ichida J. K., and Trotti D. (2014) Antisense proline-arginine RAN dipeptides linked to C9ORF72-ALS/FTD form toxic nuclear aggregates that initiate in vitro and in vivo neuronal death. Neuron 84, 1213–1225 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwon I., Xiang S., Kato M., Wu L., Theodoropoulos P., Wang T., Kim J., Yun J., Xie Y., and McKnight S. L. (2014) Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeats bind nucleoli, impede RNA biogenesis, and kill cells. Science 345, 1139–1145 10.1126/science.1254917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Y. J., Jansen-West K., Xu Y. F., Gendron T. F., Bieniek K. F., Lin W. L., Sasaguri H., Caulfield T., Hubbard J., Daughrity L., Chew J., Belzil V. V., Prudencio M., Stankowski J. N., Castanedes-Casey M., et al. (2014) Aggregation-prone c9FTD/ALS poly(GA) RAN-translated proteins cause neurotoxicity by inducing ER stress. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 505–524 10.1007/s00401-014-1336-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. May S., Hornburg D., Schludi M. H., Arzberger T., Rentzsch K., Schwenk B. M., Grässer F. A., Mori K., Kremmer E., Banzhaf-Strathmann J., Mann M., Meissner F., and Edbauer D. (2014) C9orf72 FTLD/ALS-associated Gly-Ala dipeptide repeat proteins cause neuronal toxicity and Unc119 sequestration. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 485–503 10.1007/s00401-014-1329-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flores B. N., Dulchavsky M. E., Krans A., Sawaya M. R., Paulson H. L., Todd P. K., Barmada S. J., and Ivanova M. I. (2016) Distinct C9orf72-associated dipeptide repeat structures correlate with neuronal toxicity. PLoS One 11, e0165084 10.1371/journal.pone.0165084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kearse M. G., Green K. M., Krans A., Rodriguez C. M., Linsalata A. E., Goldstrohm A. C., and Todd P. K. (2016) CGG repeat-associated non-AUG translation utilizes a cap-dependent scanning mechanism of initiation to produce toxic proteins. Mol. Cell 62, 314–322 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Green K. M., Glineburg M. R., Kearse M. G., Flores B. N., Linsalata A. E., Fedak S. J., Goldstrohm A. C., Barmada S. J., and Todd P. K. (2017) RAN translation at C9orf72-associated repeat expansions is selectively enhanced by the integrated stress response. Nat. Commun. 8, 2005 10.1038/s41467-017-02200-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tabet R., Schaeffer L., Freyermuth F., Jambeau M., Workman M., Lee C. Z., Lin C. C., Jiang J., Jansen-West K., Abou-Hamdan H., Désaubry L., Gendron T., Petrucelli L., Martin F., and Lagier-Tourenne C. (2018) CUG initiation and frameshifting enable production of dipeptide repeat proteins from ALS/FTD C9ORF72 transcripts. Nat. Commun. 9, 152 10.1038/s41467-017-02643-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheng W., Wang S., Mestre A. A., Fu C., Makarem A., Xian F., Hayes L. R., Lopez-Gonzalez R., Drenner K., Jiang J., Cleveland D. W., and Sun S. (2018) C9ORF72 GGGGCC repeat-associated non-AUG translation is upregulated by stress through eIF2α phosphorylation. Nat. Commun. 9, 51 10.1038/s41467-017-02495-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mackenzie I. R., Arzberger T., Kremmer E., Troost D., Lorenzl S., Mori K., Weng S. M., Haass C., Kretzschmar H. A., Edbauer D., and Neumann M. (2013) Dipeptide repeat protein pathology in C9ORF72 mutation cases: clinico-pathological correlations. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 859–879 10.1007/s00401-013-1181-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sonobe Y., Ghadge G., Masaki K., Sendoel A., Fuchs E., and Roos R. P. (2018) Translation of dipeptide repeat proteins from the C9ORF72 expanded repeat is associated with cellular stress. Neurobiol. Dis. 116, 155–165 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Westergard T., McAvoy K., Russell K., Wen X., Pang Y., Morris B., Pasinelli P., Trotti D., and Haeusler A. (2019) Repeat-associated non-AUG translation in C9orf72-ALS/FTD is driven by neuronal excitation and stress. EMBO Mol. Med. 11, e9423 10.15252/emmm.201809423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Su Z., Zhang Y., Gendron T. F., Bauer P. O., Chew J., Yang W. Y., Fostvedt E., Jansen-West K., Belzil V. V., Desaro P., Johnston A., Overstreet K., Oh S. Y., Todd P. K., Berry J. D., et al. (2014) Discovery of a biomarker and lead small molecules to target r(GGGGCC)-associated defects in c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 83, 1043–1050 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simone R., Balendra R., Moens T. G., Preza E., Wilson K. M., Heslegrave A., Woodling N. S., Niccoli T., Gilbert-Jaramillo J., Abdelkarim S., Clayton E. L., Clarke M., Konrad M. T., Nicoll A. J., Mitchell J. S., et al. (2018) G-quadruplex-binding small molecules ameliorate C9orf72 FTD/ALS pathology in vitro and in vivo. EMBO Mol. Med. 10, 22–31 10.15252/emmm.201707850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Disney M. D., Liu B., Yang W. Y., Sellier C., Tran T., Charlet-Berguerand N., and Childs-Disney J. L. (2012) A small molecule that targets r(CGG)(exp) and improves defects in fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 1711–1718 10.1021/cb300135h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumari D., Swaroop M., Southall N., Huang W., Zheng W., and Usdin K. (2015) High-throughput screening to identify compounds that increase fragile X mental retardation protein expression in neural stem cells differentiated from fragile X syndrome patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 800–808 10.5966/sctm.2014-0278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weisman-Shomer P., Cohen E., Hershco I., Khateb S., Wolfovitz-Barchad O., Hurley L. H., and Fry M. (2003) The cationic porphyrin TMPyP4 destabilizes the tetraplex form of the fragile X syndrome expanded sequence d(CGG)n. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3963–3970 10.1093/nar/gkg453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zamiri B., Reddy K., Macgregor R. B. Jr., and Pearson C. E. (2014) TMPyP4 porphyrin distorts RNA G-quadruplex structures of the disease-associated r(GGGGCC)n repeat of the C9orf72 gene and blocks interaction of RNA-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 4653–4659 10.1074/jbc.C113.502336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kearse M. G., Goldman D. H., Choi J., Nwaezeapu C., Liang D., Green K. M., Goldstrohm A. C., Todd P. K., Green R., and Wilusz J. E. (2019) Ribosome queuing enables non-AUG translation to be resistant to multiple protein synthesis inhibitors. Genes Dev. 33, 871–885 10.1101/gad.324715.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Starck S. R., Jiang V., Pavon-Eternod M., Prasad S., McCarthy B., Pan T., and Shastri N. (2012) Leucine-tRNA initiates at CUG start codons for protein synthesis and presentation by MHC class I. Science 336, 1719–1723 10.1126/science.1220270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ofer N., Weisman-Shomer P., Shklover J., and Fry M. (2009) The quadruplex r(CGG)n destabilizing cationic porphyrin TMPyP4 cooperates with hnRNPs to increase the translation efficiency of fragile X premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2712–2722 10.1093/nar/gkp130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang W. Y., Wilson H. D., Velagapudi S. P., and Disney M. D. (2015) Inhibition of non-ATG translational events in cells via covalent small molecules targeting RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5336–5345 10.1021/ja507448y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sebaugh J. L. (2011) Guidelines for accurate EC50/IC50 estimation. Pharm. Stat. 10, 128–134 10.1002/pst.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barmada S. J., Skibinski G., Korb E., Rao E. J., Wu J. Y., and Finkbeiner S. (2010) Cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 is toxic to neurons and enhanced by a mutation associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 30, 639–649 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barmada S. J., Ju S., Arjun A., Batarse A., Archbold H. C., Peisach D., Li X., Zhang Y., Tank E. M., Qiu H., Huang E. J., Ringe D., Petsko G. A., and Finkbeiner S. (2015) Amelioration of toxicity in neuronal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by hUPF1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7821–7826 10.1073/pnas.1509744112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flores B. N., Li X., Malik A. M., Martinez J., Beg A. A., and Barmada S. J. (2019) An intramolecular salt bridge linking TDP43 RNA binding, protein stability, and TDP43-dependent neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 27, 1133–1150.e8 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arrasate M., Mitra S., Schweitzer E. S., Segal M. R., and Finkbeiner S. (2004) Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature 431, 805–810 10.1038/nature02998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.