Abstract

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) are reprogrammed from somatic cells and are regarded as promising sources for regenerative medicine and disease research. Recently, techniques for analyses of individual cells, such as single-cell RNA-Seq and mass cytometry, have been used to understand the stem cell reprogramming process in the mouse. However, the reprogramming process in hiPSCs remains poorly understood. Here we used mass cytometry to analyze the expression of pluripotency and cell cycle markers in the reprogramming of human stem cells. We confirmed that, during reprogramming, the main cell population was shifted to an intermediate population consisting of neither fibroblasts nor hiPSCs. Detailed population analyses using computational approaches, including dimensional reduction by spanning-tree progression analysis of density-normalized events, PhenoGraph, and diffusion mapping, revealed several distinct cell clusters representing the cells along the reprogramming route. Interestingly, correlation analysis of various markers in hiPSCs revealed that the pluripotency marker TRA-1–60 behaves in a pattern that is different from other pluripotency markers. Furthermore, we found that the expression pattern of another pluripotency marker, octamer-binding protein 4 (OCT4), was distinctive in the pHistone-H3high population (M phase) of the cell cycle. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first mass cytometry–based investigation of human reprogramming and pluripotency. Our analysis elucidates several aspects of hiPSC reprogramming, including several intermediate cell clusters active during the process of reprogramming and distinctive marker expression patterns in hiPSCs.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cell, iPS cell, iPSC, reprogramming, pluripotency, cell cycle, computational biology, mass cytometry, OCT4, single-cell analysis, spanning-tree progression analysis of density-normalized events (SPADE), TRA-1–60

Introduction

Since development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)3 in the mouse and humans (1–4), there have been many efforts to understand the reprogramming process induced and coordinated by defined transcription factors, such as OCT4, SOX2, c-MYC, and KLF4 (5–14). However, research tools from traditional molecular biology and biochemistry are not sufficient for simultaneously examining the complex dynamics of the many factors involved in the reprogramming process. Recently, mass cytometry, a unique technique incorporating MS and flow cytometry using element isotope–conjugated antibodies, has provided an opportunity to monitor more than 40 factors at once with minimal spectral overlap compared with fluorescence-based cytometry (15). This powerful tool is now at the forefront of several fields, such as research regarding the hematopoietic system (16–20), cancer (21–24), and stem cells (23, 24).

A need for analytical tools that can be applied to the complex and large data sets acquired by mass cytometry has led to the development of several computational tools able to organize, analyze, and visualize such data. Dimensional reduction is the most competent concept for simplifying and visualizing multidimensional parameters in a 2D or 3D field. Spanning-tree progression analysis of density-normalized events (SPADE) was the first clustering algorithm developed for mass cytometry (25). SPADE visualizes the distribution of populations in a tree-like structure according to their marker expression patterns. SPADE also has the ability to detect small populations by applying down-sampling prior to clustering and to group cell populations according to their characteristics. viSNE is another algorithm for visualizing multidimensional data in a 2D field based on t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) (26) dimensional reduction, developed in 2013 by Amir et al. (27). PhenoGraph, another clustering tool, partitions the cells in a sample into several clusters on a 2D plane to easily identify phenotypic subpopulations (18). Metaclustering combined with PhenoGraph enables phenotypic clustering of several samples into a small number of representative groups. Recently, Cytofkit, based on R, has been developed to support analysis of mass cytometry data in various ways with a graphical user interface (28). It supports clustering based on various methods, such as ClusterX (28), PhenoGraph, and DensVM (29), followed by visualization based on several methods, such as principal-component analysis (PCA), t-SNE, and Isomap (30), as well as diffusion mapping (31), which can track differentiating cells. These methods show the high-dimensional complex heterogeneity of each population on a comprehensible 2D plane.

In the mouse reprogramming system, a few studies have used mass cytometry to investigate the reprogramming process. First, mass cytometry was used for identification of early reprogramming regulators and markers by comparison of fully and partially reprogrammed murine iPSC lines (23). The behavior of multiple markers during the reprogramming process was analyzed simultaneously using SPADE. By applying time-resolved progression analysis to mass cytometry, Zunder et al. (24) showed the dynamics that occur during reprogramming, including the time-dependent emergence of various populations and cell cycle changes in three different fibroblast reprogramming systems. These studies of the murine reprogramming system using mass cytometry greatly improved our understanding of the phases of the reprogramming process at the single-cell level. Thus, this promising technology is expected to provide an opportunity to elucidate human reprogramming and pluripotency at the single-cell level.

Distinctive cell cycle progression is one of the well-known properties of pluripotent stem cells. They exhibit a faster cell cycle with a shortened G1 and elongated S phase compared with somatic cells (24, 32). This phenomenon is caused by involvement of pluripotency markers, which aid in rapid progression through the G1/S checkpoint. To date, the contribution of many components expressed by pluripotent stem cells, such as OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and c-MYC, to progression through the G1/S checkpoint is already known (33). However, multidimensional studies of representative pluripotency and cell cycle markers and examination of their relationships have not yet been reported.

In this study, we analyzed the expression of pluripotency and cell cycle markers in the reprogramming process of human iPSCs (hiPSCs) using mass cytometry. Subsequent computational analyses, such as statistical correlation and dimensional reduction by SPADE, PhenoGraph, and diffusion mapping, were applied to investigate the reprogramming process and the relationship among the various pluripotency and cell cycle markers.

Results

Population changes during reprogramming

Because viral infection is known to affect the cell cycle checkpoints of the host cells (34–36), we utilized an episomal vector system for hiPSC reprogramming to investigate the cell cycle and pluripotency during the reprogramming process to minimize the interference of viral infection, despite its relatively lower efficiency compared with methods using viral vectors (37, 38). To select sampling time points, we first analyzed the reprogramming process on days 20 and 30. Although we observed few individual cells expressing OCT4 and NANOG on day 20, fully reprogrammed hiPSC colonies were found around day 30 (Fig. S1A). The number of alkaline phosphatase (AP)–positive colonies were increased along the reprogramming process and reached about 50 (∼0.05% efficiency) on day 30 (Fig. S1B), which is higher than in previous studies with episomal reprogramming (39, 40). These results indicate that reprogramming entered the late stage on day 20 and was completed on day 30.

To investigate the early and late stage of reprogramming, we decided to analyze days 10 and 20 of the reprogramming process as well as human fibroblasts and hiPSCs as negative and positive controls, respectively, using mass cytometry (Fig. S1C). Samples were analyzed by HeliosTM mass cytometer for 10 markers: OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, TRA-1–60, c-MYC, CD44, phospho-pRB (pRB), Cyclin B1, Ki67, and phospho-histone H3 (pHistone H3). Arc-hyperbolic sine transformation and sequential gating isolated viable singlet cells for subsequent analysis (Fig. S1D). We obtained a total of 1,153,971 cells (299,520 fibroblasts, 462,978 cells on reprogramming day 10, 147,030 cells on reprogramming day 20, and 244,442 hiPSCs) for analysis.

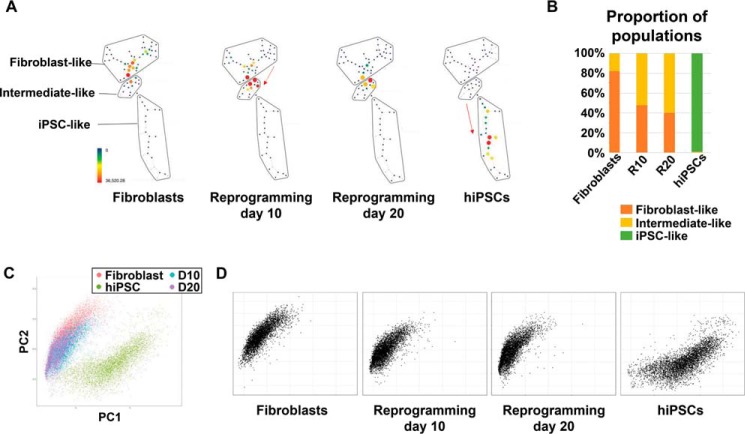

SPADE analysis clustered by pluripotency markers (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and TRA-1–60) and the fibroblast marker CD44 revealed relatively concentrated populations in stage-specific clusters at each stage (Fig. 1A). Many reports have suggested the presence of intermediate populations that appear during the reprogramming process and do not share the characteristics of the origin cells or iPSCs (4, 23, 24, 41, 42). Therefore, we grouped the cells into three clusters: a fibroblast-like population, which was mainly found in the human fibroblast sample; an iPSC-like population, which was enriched in hiPSCs; and an intermediate-like population, which was not included in the other two populations. The intermediate-like population increased over the course of the reprogramming process (50–60%), whereas the fibroblast-like and iPSC-like populations accounted for about 82% and 99% of fibroblasts and hiPSCs, respectively, implying a population shift from fibroblasts to hiPSCs during reprogramming (Fig. 1B and Table S1). This phenomenon was also observed in the PCA plot (Fig. 1C). As reprogramming proceeded, the populations shifted toward the lower right region of the PCA plot, which encompassed the hiPSC population (Fig. 1D). This reflected a decrease in CD44 expression and increase in the expression of pluripotency markers and some cell cycle signatures, such as pRB, Cyclin B1, and Ki67 (Fig. S1E).

Figure 1.

Appearance of intermediate populations during reprogramming. A, SPADE analysis clustered by pluripotency markers and CD44. Populations enriched in each stage were grouped into three clusters: fibroblast-like, intermediate-like, and iPSC-like. As reprogramming proceeded, the main population was shifted downward in the SPADE tree (red arrows). The color of each circle indicates the number of cells included in each cluster. B, proportion of each population at each stage. Intermediate-like populations accounted for more than 50% of reprogramming day 10 and 20 samples, reflecting the progression of reprogramming. C, PCA plot. Down-sampled cells (5000 per sample) were placed on the principal component (PC) plane. D, PCA plot separated by sample. A population shift during the reprogramming process was observed.

Phenotypic clustering of cells to identify distinctive populations in reprogramming

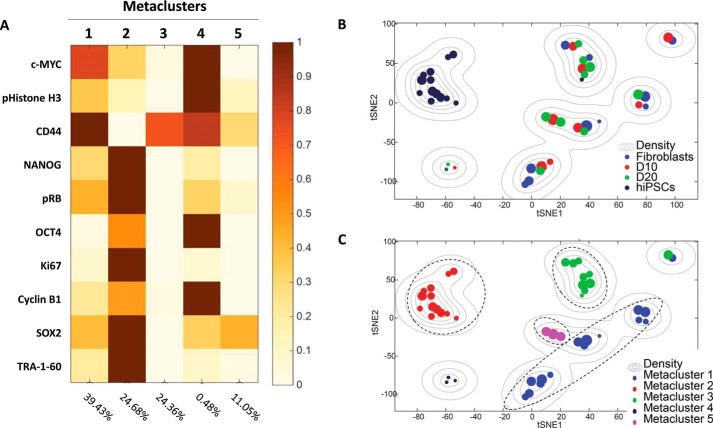

To examine which populations emerged during reprogramming from fibroblasts to hiPSCs, we employed PhenoGraph, which is an advanced t-SNE algorithm that clusters single cells according to their marker expression patterns. Using PhenoGraph, each sample was clustered and visualized on a 2D plane with two Barnes-Hut stochastic neighbor embedding axes (Fig. S2, A–D, top panels) (43) based on its marker expression patterns (Fig. S2, A–D, bottom panels). Because the expression levels of the markers in PhenoGraph heatmaps are each shown as a relative value from 0 to 1 separately, a total of 44 clusters representing expression changes occurring during the reprogramming process is presented in a single heatmap (Fig. S2E). Based on this, metaclustering was performed to investigate the clusters by their phenotypes throughout the reprogramming process. As a result, the 44 clusters were again clustered into five metaclusters (Fig. 2A) and are shown on the t-SNE map with colors indicating the samples and metaclusters (Fig. 2, B and C).

Figure 2.

Phenotypic clustering of cells during reprogramming by PhenoGraph and metaclustering. A, metaclusters based on the PhenoGraph algorithm. All clusters were classified into five metaclusters depending on their marker expression patterns. Each metacluster showed various phenotypes, including fibroblast-like, iPSC-like, and reprogramming-like phenotypes. B and C, t-SNE map of the clusters labeled by sample (B) and metacluster (C). Metaclusters showed the heterogeneity of each population except hiPSCs, which were mostly found in metacluster 2. Metacluster 5 consisted of only cells from reprogramming days 10 and 20.

Metacluster 1 showed a fibroblast-like phenotype with high expression of CD44 that was observed in fibroblasts and reprogramming cells on days 10 and 20 (Fig. 2, B and C). Metacluster 2 exhibited a pluripotent cell–like phenotype with high expression of pluripotency markers such as TRA-1–60, SOX2, OCT4, and NANOG and no expression of fibroblast marker CD44. Consistent with this, most clusters classified into metacluster 2 were found in the hiPSC sample (Fig. 2, B and C). Interestingly, metaclusters 3 and 5 were mostly found in cells during the reprogramming process (Fig. 2, B and C). Metacluster 3 exhibited low expression of most of markers except CD44, implying that the cells in this metacluster were in a nonproliferating state based on their lack of cell cycle marker expression. Some cells in the fibroblast sample were also included in this cluster, indicating that these cells were unlikely to achieve pluripotency. Metacluster 5 exhibited further reduction in CD44 expression and a slight increase in SOX2 expression (Fig. 2, B and C, and Fig. S2, F and G). In particular, the three clusters (clusters 12, 23, and 24) in metacluster 5 consisted of cells from reprogramming days 10 and 20 only (Fig. 2, B and C), which may imply establishment of reprogramming-prone populations by successful expression of reprogramming factors. It has been reported that SOX2 is the first factor expressed during the hierarchical phase of reprogramming after the stochastic phase and that it plays an indispensable role in activation of the pluripotency circuit (7). In contrast, metacluster 4 contained a small number of cells expressing various markers, such as SOX2, Cyclin B1, OCT4, pRB, NANOG, CD44, pHistone H3, and c-MYC. These cells may be mixture of reprogrammed cells; however, fibroblasts that were not transfected with reprogramming factors were also contained within this population (Fig. 2, B and C, and Figs. S2A and S3E). This suggests that the clusters contained in metacluster 4 should be considered outliers as a result of nonspecific antibody binding. Based on these results, we could identify the appearance of various cell populations during the reprogramming process and classify them into several groups, including cells in the reprogramming process.

Reprogramming aspects identified by diffusion map analysis

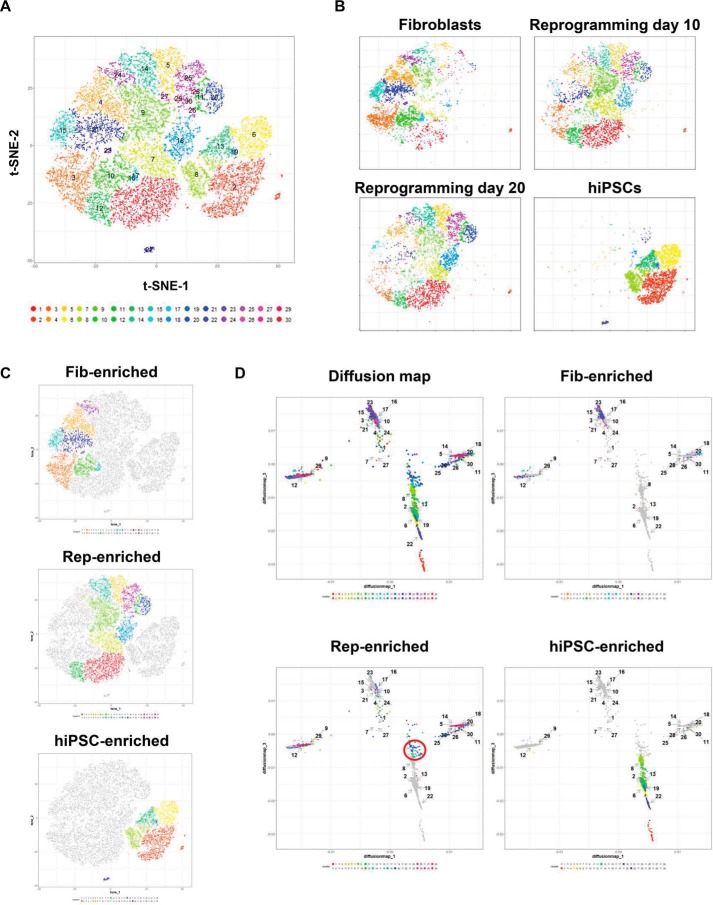

For a more detailed analysis of reprogramming, we employed Cytofkit, a multifunctional clustering and visualization tool for mass cytometry (28). All samples were clustered into 30 subclusters on the same t-SNE plane using the PhenoGraph algorithm (Fig. 3A). Similar to the earlier results, samples from reprogramming days 10 and 20 occupied positions on the plane between those of fibroblasts and hiPSCs (Fig. 3B). For simplified examination of the reprogramming process based on clustering, clusters were classified into three groups according to their expression changes during reprogramming: fibroblast-enriched, reprogramming-enriched, and hiPSC-enriched clusters (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3A and Table S2). As a result, nine, 14, and six clusters were found to belong to each group, respectively (Fig. S3B). The fibroblast-enriched clusters clearly showed high expression of CD44, whereas the reprogramming-enriched clusters showed reduced expression of CD44 and heterogeneous expression of other markers (Fig. S3C).

Figure 3.

Diffusion map analysis of reprogramming. A, clustering of all samples by PhenoGraph algorithm on Cytofkit, with 30 clusters generated. B, distribution of cells in each sample. A population shift was observed during reprogramming. C, clusters were classified into stage-enriched clusters: fibroblast-enriched (Fib), reprogramming-enriched (Rep), and hiPSC-enriched clusters mainly include fibroblasts, cells during reprogramming, and hiPSCs, respectively. D, diffusion map analysis of reprogramming. The position of each cluster is shown, and fibroblast-, reprogramming-, and hiPSC-enriched clusters are indicated.

Using these clusters, we examined the reprogramming process using diffusion mapping, which was developed for single-cell analysis of differentiation data (31), using Cytofkit. Each cluster from Fig. 3A was displayed with the same color in the diffusion map and highlighted separately by each population-enriched cluster (Fig. 3D). The fibroblast-enriched population was located in the upper area of the diffusion map, and as reprogramming proceeded, the placement of each cluster moved downward. In reprogramming-enriched populations, two major populations were observed in addition to a few cells falling near the hiPSC-enriched population, indicated by the red circle in the bottom left panel in Fig. 3D. According to the expression pattern of each marker along the diffusion map axes (Fig. S3D), the two reprogramming-enriched populations, separated to the distal side of diffusion map component 1, showed slight differences in the expression of markers. However, the positions of most cells in those two populations on the diffusion map plane were relatively distant from that of the hiPSCs. Thus, we focused on the few cells observed near the hiPSC-enriched population. Although these cells were derived from various clusters, most belonged to clusters 18 and 20 (Fig. S3E, left panel). These two clusters occupied the position nearest the hiPSCs in both the PCA plot and t-SNE map (Fig. S3E, center and right panel, respectively), which implies that they exhibit phenotypes most similar to hiPSCs among the cells in the reprogramming process. Given the expression pattern of metacluster 5 in the previous analysis (Fig. 2A), cluster 18 likely contained reprogrammed cells. Based on these results, we speculate that at least SOX2 and perhaps pHistone-H3 expression is necessary for reprogramming

Relationship of pluripotency and cell cycle markers in hiPSCs

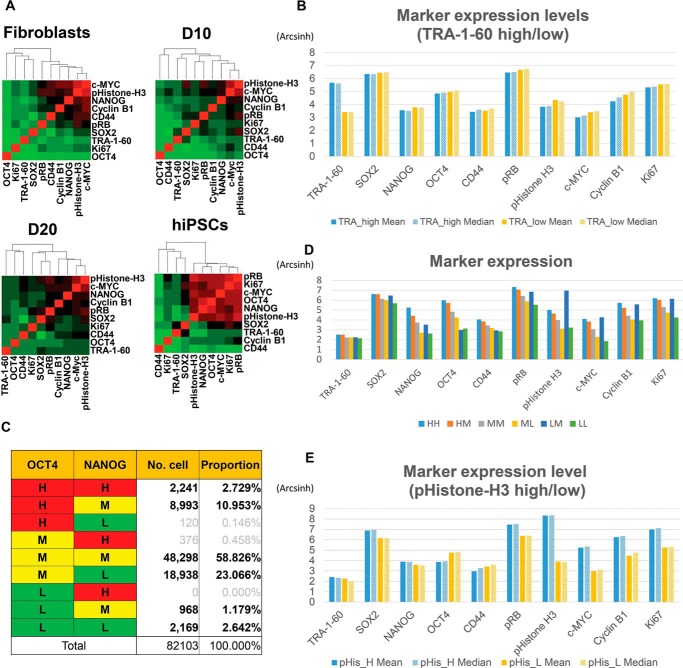

After necessary and in-depth classification by marker expression, we sought to examine the relationships among markers. viSNE was performed with CD44 and the pluripotency markers OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and TRA-1–60 (Fig. S4A). The distributions of cells indicated that fibroblasts and cells in the reprogramming process shared a high proportion of the population, whereas iPSCs were totally distinct from other samples because of their high expression of pluripotency markers, as expected. In terms of cell cycle markers, most of the markers showed a similar gradient pattern, implying high correlation among those markers. To quantify the correlation between each pair of markers, Spearman's rank correlations were calculated (Table S3). Hierarchical clustering of correlations among markers within each sample revealed a highly conserved correlation between c-MYC and pHistone H3 (Fig. 4A). This result is consistent with previous reports showing that pHistone H3 is a functional downstream target of c-MYC (44). In addition, hiPSCs also exhibited strong correlations among pRB, Ki67, and OCT4 (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Relationships among pluripotency and cell cycle markers in hiPSCs. A, hierarchical clustering based on Spearman's correlation coefficients between each pair of markers in individual samples. B, marker expression patterns in TRA-1–60high and TRA-1–60low populations, showing no significant difference between the two populations. C, classification of cells according to OCT4 and NANOG expression levels. The number and proportion of cells in each group are shown. D, marker expression levels of each group. Cell cycle marker expression is shown in proportion to OCT4 and NANOG expression. The LM population exhibited exceptionally high cell cycle marker levels. E, marker expression levels in pHistone-H3high and pHistone-H3low populations. Most markers showed higher expression in pHistone-H3high, except OCT4.

Because strong correlations among the markers were observed only in hiPSCs (likely because of the lack of pluripotency markers in other samples), we focused on hiPSCs for further analysis. For a more accurate calculation of correlations between markers, we sought to exclude cells that spontaneously differentiated during culture and those abnormally unmarked by antibodies; we identified 82,103 undifferentiated hiPSCs that expressed the pluripotency markers OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and TRA-1–60 at levels higher than 95% of fibroblasts (OSNT-gated population). Gated cells showed similar correlations between each pair of markers as the total hiPSC sample (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4B). Gating was also used to remove nonproliferating cells expressing low levels of cell cycle markers, such as Ki67, pRB, and pHistone-H3 (Fig. S4C). In the resulting sample, we revisited the relationships among pluripotency markers. Unexpectedly, TRA-1–60 appeared to behave differently than the other pluripotency markers, with weak correlations with other markers in both the viable and OSNT-gated populations (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4B). Because TRA-1–60 expression in the OSNT-gated population revealed two distinct populations, TRA-1–60low and TRA-1–60high (Fig. S4, D and E), we analyzed the expression level of each marker in each of these populations (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, pluripotency and cell cycle markers showed a similar expression pattern between the TRA-1–60low and the TRA-1–60high populations. This result suggests the possibility that TRA-1–60, known as a critical marker for the fully reprogrammed state (45), is independent of the core pluripotency circuit consisting of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG in hiPSCs.

Next we classified OSNT-gated cells into nine subgroups according to the expression levels of OCT4 and NANOG (Fig. 4C). SOX2 and TRA-1–60 were excluded because of their uniform expression in hiPSCs and weak correlation with other markers, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). OCT4 and NANOG expression was divided into high, medium, and low (Fig. S4, D and E). After removing subgroups accounting for less than 1% of cells (Fig. 4C, gray text), six subgroups were analyzed further. Expression of most markers decreased as OCT4 and NANOG expression decreased, with the exception of cell cycle markers in the OCT4low and NANOGmid (LM) population (Fig. 4D). It is generally known that pluripotency and cell cycle progression are tightly linked and regulate each other (24, 32, 33, 46). In this analysis, however, the LM population exhibited high expression of cell cycle markers, especially pHistone-H3. Because pHistone-H3 is a well-known marker expressed during mitosis or meiosis (47), this result implies a distinctive behavior of pluripotency markers during M phase of the cell cycle. We next compared the marker expression levels in M phase (pHistone-H3high population) with those in other populations (pHistone-H3low population) in hiPSCs (Fig. S4F). Interestingly, OCT4 showed the opposite expression pattern from most markers, including cell cycle markers and other pluripotency markers such as SOX2 and NANOG, which were highly expressed in the pHistone-H3high population (Fig. 4E). The OCT4 expression level in the pHistone-H3low population was about 2-fold higher than that in the pHistone-H3high population (Fig. S4G). This result implies the distinct regulation of OCT4 during cell cycle progression in the pluripotent state. Taken together, our results indicate that, using in-depth single cell analysis with various pluripotency and cell cycle markers, we were able to precisely look into the relationships between markers and discover unexpected regulatory aspects of TRA-1–60 and OCT4 in regard to pluripotency and the cell cycle, respectively, in hiPSCs.

Discussion

Compared with traditional omics studies, single-cell analyses provide ultimate resolution for investigations of complex processes with heterogeneous populations such as iPSC reprograming. Many tools have been developed for single-cell analyses of cellular component expression, with single-cell RNA-Seq and mass cytometry among the most popular tools for the analysis of mRNA and epitope expression levels, respectively. Single-cell RNA-Seq enables acquisition of the entire transcriptome of each cell. However, the number of cells that can be analyzed is restricted by cost and technical limitations. Although mass cytometry allows examination of fewer markers than single-cell RNA-Seq, the number of markers included is greater than for any other fluorescent dye–labeled antibody-based cytometry. Mass cytometry also has the advantages of allowing analysis of an unlimited number of cells and detection of epitopes that cannot be analyzed using mRNA sequences, such as analysis of proteins that undergo post-translational modification, polysaccharides, or lipids. Here we analyzed human somatic reprogramming using mass cytometry, as we needed to acquire a large number of cells because of the low efficiency of human reprogramming. As this new technology has not yet been employed to examine the human reprogramming process, we analyzed reprogramming from the macroscopic to microscopic level by investigating population shifts, the emergence of various cell populations, the reprogramming route, and the relationships among pluripotency and cell cycle markers. Based on these results, we provide new insights into pluripotency and cell cycle regulation regarding TRA-1–60 and pHistone-H3, which cannot be analyzed with conventional RNA-Seq.

In our analysis, pluripotency and cell cycle markers such as pRB, Ki67, c-MYC, OCT4, NANOG, and pHistone-H3 were clustered based on their strong correlation in hiPSCs. Strong correlation between several pluripotency and cell cycle markers in hiPSCs implies that the proliferation of iPSCs may be strongly associated with the expression of pluripotency markers as known to date (24, 32, 33, 46, 48). Interestingly, two pluripotency markers, SOX2 and TRA-1–60, did not exhibit strong correlations, even with OCT4 and NANOG. SOX2 was similarly expressed in all cells, whereas TRA-1–60 showed differential expression and was not correlated with any other pluripotency marker expression in hiPSCs. TRA-1–60 epitope is a sialylated keratan sulfate proteoglycan that is expressed on podocalyxin in some pluripotent cells, including embryonic carcinoma cells as well as pluripotent stem cells (49–51). However, its regulatory mechanism and relationship with other pluripotency network components remain unclear. It is known that the molecular mass of podocalyxin is changed and that the epitope is no longer detected by TRA-1–60 antibody along with differentiation (51). Knockout of podocalyxin in human embryonic stem cells results in a decreases in TRA-1–60 but does not disrupt maintenance of pluripotency (52). As other pluripotent stem cell-specific glycosphingolipid surface antigens, i.e. stage-specific embryonic antigen 3 (SSEA-3) and SSEA-4, are dispensable for maintaining pluripotency and differentiation in vitro and in vivo (53), we assume that TRA-1–60 may also be a marker for human pluripotent stem cells and independent of the core pluripotency network.

The expression levels of OCT4 and NANOG tended to be correlated with those of cell cycle markers. Intriguingly, we found that the LM population showed high levels of cell cycle markers, especially the M phase marker pHistone-H3. In addition, OCT4 showed the opposite trend compared with the other markers. This result implies that the expression of some pluripotency markers may not be constant but oscillate during cell cycle progression. It has been reported that the expression of pluripotency marker genes such as NANOG, TERF1, PRDM14, and TDGF1 may increase during the cell cycle, mainly at S-G2 phase, to maintain pluripotency (46). It makes sense for pluripotency markers to be observed at high levels in S-G2 phase because many pluripotency markers are involved in regulation of the G1/S checkpoint for rapid cell cycle progression in hiPSCs (33). Another study reported that the differentiation potential of hiPSCs varies at each stage of the cell cycle and is especially restricted at M phase (54). This could be a clue regarding the relationship between OCT4 decreases and pHistone-H3 increases in terms of restricted differentiation and chromosome condensation during mitotic phases. Thus, further study is needed to clarify this possibility regarding the nature of pluripotency markers during cell cycle progression.

In this study, we first analyzed the human reprogramming process and pluripotency in terms of pluripotency and cell cycle markers using mass cytometry. Our results showed that mass cytometry can reproduce previous results as well as produce new findings, demonstrating its reliability and effectiveness, respectively. Mass cytometry and its analytical tools are helpful for understanding multidimensional aspects of biological processes by analyzing multiple combinations of various markers in which posttranscriptional or posttranslational markers are included. This enables laborious and time-consuming analyses with numerous markers to be replaced with a single experiment. Our research suggests that mass cytometry is an invaluable tool for complex research involving the reprogramming process, pluripotency, and other stem cell phenomena as well as phenotyping of heterogeneity in cancer or other diseases.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and reprogramming human fibroblasts into hiPSCs

Human CRL-2097 fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). A hiPSC line derived from CRL-2097 (ATCC) was maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 20% KnockOutTM Serum Replacement (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). For cellular reprogramming, CRL-2097 cells were transfected with three episomal expression vectors, pCXLE-OCT3/4-shP53, pCXLE-l-myc-Lin28, and pCXLE-SOX2-KLF4 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA), with the NeonTM transfection system and transfection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Electroporation conditions were as follows: pulse voltage, 1650; pulse width, 10; pulse number, 3. For reprogramming, transfected cells were plated on the culture dish at 10,000 cells/cm2 density and cultured with hiPSC medium–based conditioned medium from a culture of γ-irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells in hiPSC medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor, 1 mm nicotinamide, and 10 mm Y-27632 (Tocris, Bristol, UK). The medium was changed every 2 days. Samples were collected on days 10 and 20 after transfection. As a negative and positive control, CRL-2097 fibroblasts and their derivative iPSC lines, respectively, were also collected.

Alkaline phosphatase analysis

As described previously (55), samples were washed once with PBS (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) and fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 s, followed by staining with AP staining solution for 15 min in the dark. AP-stained colonies were counted on days 20 and 30 of reprogramming to check reprogramming efficiency.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Samples were washed once with PBS (Welgene) and fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min, followed by three washes with PBS. Blocking and permeabilization were done with 3% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 solution in PBS for 1 h. Primary antibodies were diluted in 1% BSA and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After 1 h of washing, samples were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa-488 or Alexa-594 (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 diluted in 0.1% BSA. All procedures were performed at room temperature unless indicated otherwise.

Mass cytometry

Mass cytometry was performed with HeliosTM (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells, including CRL-2097, hiPSCs, and reprogramming day 10 and 20 cells, were detached from dishes at each stage and resuspended in Maxpar® Cell Staining Buffer (Fluidigm) for barcoding. Prior to barcoding, dead cells were stained by Cell-IDTM cisplatin reagent (Fluidigm), followed by fixation with Maxpar® Fix I Buffer (Fluidigm). Samples were barcoded and blocked with Fc-blocking solution. Then samples were stained with Maxpar® metal-conjugated antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, c-MYC, TRA-1–60, CD44, Cyclin B1, pRB (Ser-807/Ser-811), phospho-histone H3 (Ser-28), and Ki67 included in the Maxpar® ESC/iPSC Phenotyping Panel Kit and Maxpar® Cell Cycle Panel Kit (Fluidigm). The expression pattern of each sample was acquired on the HeliosTM mass cytometer and exported in flow cytometry standard (FCS) format.

Computational analysis of mass cytometry data

For data analysis, raw FCS files were normalized and debarcoded using HeliosTM preinstalled software prior to analysis using the web-based tool Cytobank, the R-based Cytofkit (28), and the Matlab-based open source analytic tool CYT (27, 56). The FCS files were transformed using an inverse hyperbolic sine (arcsinh) function with a cofactor of 5 and pregated manually to exclude EQ beads, cell debris, cell doublets, and dead cells (Fig. S1D). SPADE and viSNE analyses were performed via Cytobank. SPADE analysis was performed with 50 nodes and 1% target down-sampled events. PhenoGraph and metaclustering were done on gated cells (3500 cells) (18). The number of neighbors (k parameter) used in PhenoGraph clustering was set to 30, the default number in the CYT program. For metaclustering, the k parameter was set to 8. All data representing clusters in each sample were expressed as heatmaps and Barnes-Hut stochastic neighbor embedding fields. Cytofkit was used for cell clustering with the PhenoGraph method, PCA, and analysis of the reprogramming route by diffusion mapping (Fig. 3). The default settings of Cytofkit were used for the analyses.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and visualization of graphs were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and R. Calculation of Spearman's correlation coefficients and visualization of hierarchy clustering were performed using R.

Author contributions

I. I., M.-Y. S., and J. K. conceptualization; I. I., B.-E. T., K.-B. L., M.-Y. S., and J. K. data curation; I. I. software; I. I., Y. S. S., K. B. J., and B.-E. T. formal analysis; I. I. validation; I. I., Y. S. S., I. K., and K.-B. L. investigation; I. I. visualization; I. I., Y. S. S., K. B. J., and I. K. methodology; I. I. writing-original draft; I. I., M.-Y. S., and J. K. writing-review and editing; Y. S. S. and K. B. J. resources; M.-Y. S. and J. K. supervision; J. K. funding acquisition; J. K. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Byung-kook Min from the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, who helped calculate statistical correlations between the markers.

This work was supported by the Samsung Research Funding Center of Samsung Electronics under Project SRFC-MA1601-06 and a Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology initiative program. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1–S4.

- iPSC

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- SPADE

- Spanning-tree progression analysis of density-normalized events

- t-SNE

- t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

- PCA

- principal component analysis

- AP

- alkaline phosphatase

- hiPSC

- human induced pluripotent stem cell

- FCS

- flow cytometry standard

- PC

- principal component.

References

- 1. Takahashi K., and Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., and Yamanaka S. (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu J., Vodyanik M. A., Smuga-Otto K., Antosiewicz-Bourget J., Frane J. L., Tian S., Nie J., Jonsdottir G. A., Ruotti V., Stewart R., Slukvin I. I., and Thomson J. A. (2007) Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 10.1126/science.1151526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park I. H., Zhao R., West J. A., Yabuuchi A., Huo H., Ince T. A., Lerou P. H., Lensch M. W., and Daley G. Q. (2008) Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 451, 141–146 10.1038/nature06534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buganim Y., Faddah D. A., and Jaenisch R. (2013) Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 427–439 10.1038/nrg3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Golipour A., David L., Liu Y., Jayakumaran G., Hirsch C. L., Trcka D., and Wrana J. L. (2012) A late transition in somatic cell reprogramming requires regulators distinct from the pluripotency network. Cell Stem Cell 11, 769–782 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jaenisch R., and Young R. (2008) Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell 132, 567–582 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li R., Liang J., Ni S., Zhou T., Qing X., Li H., He W., Chen J., Li F., Zhuang Q., Qin B., Xu J., Li W., Yang J., Gan Y., et al. (2010) A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 7, 51–63 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pasque V., Miyamoto K., and Gurdon J. B. (2010) Efficiencies and mechanisms of nuclear reprogramming. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 75, 189–200 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Polo J. M., Anderssen E., Walsh R. M., Schwarz B. A., Nefzger C. M., Lim S. M., Borkent M., Apostolou E., Alaei S., Cloutier J., Bar-Nur O., Cheloufi S., Stadtfeld M., Figueroa M. E., Robinton D., et al. (2012) A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell 151, 1617–1632 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Samavarchi-Tehrani P., Golipour A., David L., Sung H. K., Beyer T. A., Datti A., Woltjen K., Nagy A., and Wrana J. L. (2010) Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 7, 64–77 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stadtfeld M., and Hochedlinger K. (2010) Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications. Genes Dev. 24, 2239–2263 10.1101/gad.1963910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vierbuchen T., and Wernig M. (2012) Molecular roadblocks for cellular reprogramming. Mol. Cell 47, 827–838 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao Y., Zhao T., Guan J., Zhang X., Fu Y., Ye J., Zhu J., Meng G., Ge J., Yang S., Cheng L., Du Y., Zhao C., Wang T., Su L., et al. (2015) A XEN-like state bridges somatic cells to pluripotency during chemical reprogramming. Cell 163, 1678–1691 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bandura D. R., Baranov V. I., Ornatsky O. I., Antonov A., Kinach R., Lou X., Pavlov S., Vorobiev S., Dick J. E., and Tanner S. D. (2009) Mass cytometry: technique for real time single cell multitarget immunoassay based on inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81, 6813–6822 10.1021/ac901049w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bendall S. C., Davis K. L., Amir el-A. D., Tadmor M. D., Simonds E. F., Chen T. J., Shenfeld D. K., Nolan G. P., and Pe'er D. (2014) Single-cell trajectory detection uncovers progression and regulatory coordination in human B cell development. Cell 157, 714–725 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cols M., Rahman A., Maglione P. J., Garcia-Carmona Y., Simchoni N., Ko H. M., Radigan L., Cerutti A., Blankenship D., Pascual V., and Cunningham-Rundles C. (2016) Expansion of inflammatory innate lymphoid cells in patients with common variable immune deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 1206–1215.e6 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levine J. H., Simonds E. F., Bendall S. C., Davis K. L., Amir el-A. D., Tadmor M. D., Litvin O., Fienberg H. G., Jager A., Zunder E. R., Finck R., Gedman A. L., Radtke I., Downing J. R., Pe'er D., and Nolan G. P. (2015) Data-driven phenotypic dissection of AML reveals progenitor-like cells that correlate with prognosis. Cell 162, 184–197 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saeys Y., Van Gassen S., and Lambrecht B. N. (2016) Computational flow cytometry: helping to make sense of high-dimensional immunology data. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 449–462 10.1038/nri.2016.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strauss-Albee D. M., Fukuyama J., Liang E. C., Yao Y., Jarrell J. A., Drake A. L., Kinuthia J., Montgomery R. R., John-Stewart G., Holmes S., and Blish C. A. (2015) Human NK cell repertoire diversity reflects immune experience and correlates with viral susceptibility. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 297ra115 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Behbehani G. K., Bendall S. C., Clutter M. R., Fantl W. J., and Nolan G. P. (2012) Single-cell mass cytometry adapted to measurements of the cell cycle. Cytometry A 81, 552–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giesen C., Wang H. A., Schapiro D., Zivanovic N., Jacobs A., Hattendorf B., Schüffler P. J., Grolimund D., Buhmann J. M., Brandt S., Varga Z., Wild P. J., Günther D., and Bodenmiller B. (2014) Highly multiplexed imaging of tumor tissues with subcellular resolution by mass cytometry. Nat. Methods 11, 417–422 10.1038/nmeth.2869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lujan E., Zunder E. R., Ng Y. H., Goronzy I. N., Nolan G. P., and Wernig M. (2015) Early reprogramming regulators identified by prospective isolation and mass cytometry. Nature 521, 352–356 10.1038/nature14274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zunder E. R., Lujan E., Goltsev Y., Wernig M., and Nolan G. P. (2015) A continuous molecular roadmap to iPSC reprogramming through progression analysis of single-cell mass cytometry. Cell Stem Cell 16, 323–337 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qiu P., Simonds E. F., Bendall S. C., Gibbs K. D. Jr., Bruggner R. V., Linderman M. D., Sachs K., Nolan G. P., and Plevritis S. K. (2011) Extracting a cellular hierarchy from high-dimensional cytometry data with SPADE. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 886–891 10.1038/nbt.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laurens van der Maaten G. H. (2008) Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research 9, 2579–2605 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amir el-A.D., Davis K. L., Tadmor M. D., Simonds E. F., Levine J. H., Bendall S. C., Shenfeld D. K., Krishnaswamy S., Nolan G. P., and Pe'er D. (2013) viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 545–552 10.1038/nbt.2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen H., Lau M. C., Wong M. T., Newell E. W., Poidinger M., and Chen J. (2016) Cytofkit: a Bioconductor package for an integrated mass cytometry data analysis pipeline. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1005112 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Becher B., Schlitzer A., Chen J., Mair F., Sumatoh H. R., Teng K. W., Low D., Ruedl C., Riccardi-Castagnoli P., Poidinger M., Greter M., Ginhoux F., and Newell E. W. (2014) High-dimensional analysis of the murine myeloid cell system. Nat. Immunol. 15, 1181–1189 10.1038/ni.3006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tenenbaum J. B., de Silva V., and Langford J. C. (2000) A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Science 290, 2319–2323 10.1126/science.290.5500.2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haghverdi L., Buettner F., and Theis F. J. (2015) Diffusion maps for high-dimensional single-cell analysis of differentiation data. Bioinformatics 31, 2989–2998 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hindley C., and Philpott A. (2013) The cell cycle and pluripotency. Biochem. J. 451, 135–143 10.1042/BJ20121627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu L., Michowski W., Inuzuka H., Shimizu K., Nihira N. T., Chick J. M., Li N., Geng Y., Meng A. Y., Ordureau A., Kołodziejczyk A., Ligon K. L., Bronson R. T., Polyak K., Harper J. W., et al. (2017) G1 cyclins link proliferation, pluripotency and differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 177–188 10.1038/ncb3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bagga S., and Bouchard M. J. (2014) Cell cycle regulation during viral infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 1170, 165–227 10.1007/978-1-4939-0888-2_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Emmett S. R., Dove B., Mahoney L., Wurm T., and Hiscox J. A. (2005) The cell cycle and virus infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 296, 197–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katz R. A., Greger J. G., and Skalka A. M. (2005) Effects of cell cycle status on early events in retroviral replication. J. Cell Biochem. 94, 880–889 10.1002/jcb.20358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okita K., Hong H., Takahashi K., and Yamanaka S. (2010) Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells with plasmid vectors. Nat. Protoc. 5, 418–428 10.1038/nprot.2009.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou Y. Y., and Zeng F. (2013) Integration-free methods for generating induced pluripotent stem cells. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 11, 284–287 10.1016/j.gpb.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bang J. S., Choi N. Y., Lee M., Ko K., Lee H. J., Park Y. S., Jeong D., Chung H. M., and Ko K. (2018) Optimization of episomal reprogramming for generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from fibroblasts. Anim. Cells Syst. (Seoul) 22, 132–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu J., Hu K., Smuga-Otto K., Tian S., Stewart R., Slukvin I. I., and Thomson J. A. (2009) Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science 324, 797–801 10.1126/science.1172482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Efe J. A., Hilcove S., Kim J., Zhou H., Ouyang K., Wang G., Chen J., and Ding S. (2011) Conversion of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using a direct reprogramming strategy. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 215–222 10.1038/ncb2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim J., Efe J. A., Zhu S., Talantova M., Yuan X., Wang S., Lipton S. A., Zhang K., and Ding S. (2011) Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7838–7843 10.1073/pnas.1103113108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maaten Lv. d. (2014) Accelerating t-SNE using tree-based algorithms. Journal of Machine Learning Research 15, 1–21 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang Q., Zhong Q., Evans A. G., Levy D., and Zhong S. (2011) Phosphorylation of histone H3 serine 28 modulates RNA polymerase III-dependent transcription. Oncogene 30, 3943–3952 10.1038/onc.2011.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chan E. M., Ratanasirintrawoot S., Park I. H., Manos P. D., Loh Y. H., Huo H., Miller J. D., Hartung O., Rho J., Ince T. A., Daley G. Q., and Schlaeger T. M. (2009) Live cell imaging distinguishes bona fide human iPS cells from partially reprogrammed cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 1033–1037 10.1038/nbt.1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gonzales K. A., Liang H., Lim Y. S., Chan Y. S., Yeo J. C., Tan C. P., Gao B., Le B., Tan Z. Y., Low K. Y., Liou Y. C., Bard F., and Ng H. H. (2015) Deterministic Restriction on pluripotent state dissolution by cell-cycle pathways. Cell 162, 564–579 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hans F., and Dimitrov S. (2001) Histone H3 phosphorylation and cell division. Oncogene 20, 3021–3027 10.1038/sj.onc.1204326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schoeftner S., Scarola M., Comisso E., Schneider C., and Benetti R. (2013) An Oct4-pRb axis, controlled by MiR-335, integrates stem cell self-renewal and cell cycle control. Stem Cells 31, 717–728 10.1002/stem.1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Andrews P. W., Banting G., Damjanov I., Arnaud D., and Avner P. (1984) Three monoclonal antibodies defining distinct differentiation antigens associated with different high molecular weight polypeptides on the surface of human embryonal carcinoma cells. Hybridoma 3, 347–361 10.1089/hyb.1984.3.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Badcock G., Pigott C., Goepel J., and Andrews P. W. (1999) The human embryonal carcinoma marker antigen TRA-1–60 is a sialylated keratan sulfate proteoglycan. Cancer Res. 59, 4715–4719 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schopperle W. M., and DeWolf W. C. (2007) The TRA-1–60 and TRA-1–81 human pluripotent stem cell markers are expressed on podocalyxin in embryonal carcinoma. Stem Cells 25, 723–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Freedman B. S., Brooks C. R., Lam A. Q., Fu H., Morizane R., Agrawal V., Saad A. F., Li M. K., Hughes M. R., Werff R. V., Peters D. T., Lu J., Baccei A., Siedlecki A. M., Valerius M. T., et al. (2015) Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nat. Commun. 6, 8715 10.1038/ncomms9715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brimble S. N., Sherrer E. S., Uhl E. W., Wang E., Kelly S., Merrill A. H. Jr, Robins A. J., and Schulz T. C. (2007) The cell surface glycosphingolipids SSEA-3 and SSEA-4 are not essential for human ESC pluripotency. Stem Cells 25, 54–62 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pauklin S., and Vallier L. (2013) The cell-cycle state of stem cells determines cell fate propensity. Cell 155, 135–147 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Son M. Y., Sim H., Son Y. S., Jung K. B., Lee M. O., Oh J. H., Chung S. K., Jung C. R., and Kim J. (2017) Distinctive genomic signature of neural and intestinal organoids from familial Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 43, 584–603 10.1111/nan.12396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kotecha N., Krutzik P. O., and Irish J. M. (2010) Web-based analysis and publication of flow cytometry experiments. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. Chapter 10, Unit 10.17 10.1002/0471142956.cy1017s53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.