Abstract

Background

This study represents figures from a cardiac care unit (CCU) of a university hospital; it describes an example of a tertiary academic center in Egypt and provides an epidemiological view of the female HF patients, their risk profile, and short-term outcome during hospitalization.

Results

It is a local single-center cross-sectional observational registry of CCU patients 1 year from July 2015 to July 2016. Patient’s data were collected through a special software program. Women with evidence of HF were thoroughly studied.

Among the 1006 patients admitted to CCU in 1 year, 345 (34.2%) patients were females and 118 (34.2%) had evidence of HF, whereas 661 (65.7%) were males and 178 (26.9%) of them had HF. Women with HF showed 11.7% prevalence of the total population admitted to CCU. 72.7% were HFrEF and 27.3% were HFpEF. Compared to men, women with HF were older in age, more obese, less symptomatic than men, had higher incidence of associated co-morbidities, less likely to be re-admitted for HF, and less likely to have ACS and PCI. Valvular heart diseases and cardiomyopathies were the commonest etiologies of their HF. Women had more frequent normal ECG, higher EF%, and smaller LA size. There is no difference in medications and CCU procedures. While females had shorter stay, there is no significant difference in hospital mortality compared to male patients.

Conclusions

Despite higher prevalence of HF in females admitted to CCU and different clinical characteristics and etiology of HF, female gender was associated with similar prognosis during hospital course compared to male gender.

Keywords: Heart failure, Gender difference, Women hospital mortality

Background

Heart failure is a growing health challenge and among the major causes of death in developing countries along with the progression of the aging society, particularly in women [1, 2].

It has been generally accepted that female gender is associated with better survival (either crude and/or age-adjusted) compared with male gender in the broad spectrum of HF especially of a non-ischemic etiology, while other registries demonstrated no differences in the prognoses of male and female patients [3].

In the few studies from low-income countries, the gender distribution appears equal but age is much lower than in developed countries [4]. Etiologies have previously varied but recent studies suggest that HF in these countries increasingly shifts towards the pattern seen in developed countries with regard to risk factors, etiology, and comorbidity [5].

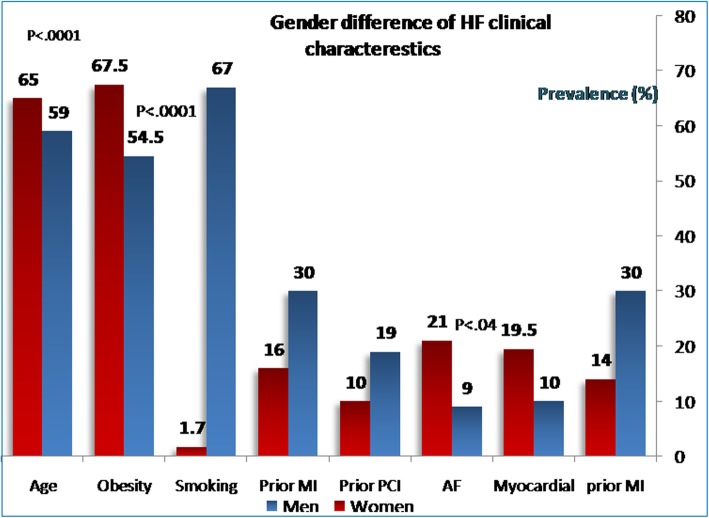

It continues to be mandatory to clarify, however, whether gender differences exist among Egyptian acute HF patients. Thus, in the present study, we addressed clinical characteristics and in-hospital management/outcomes of women using acute HF registry database (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gender difference of HF clinical characteristics

Methods

Baseline patient data

The present study is a single-center, prospective observational study. We enrolled 1006 consecutive patients > 18 years old with emergency admission to the CCU in university hospitals, a representative to tertiary academic center in Egypt between July 2015 and July 2016. Patients included in the study were those hospitalized due to worsening HF or new onset as the leading cause of admission. Patients in stages C–D HF were included in focused analysis [6]. The diagnosis of HF was based on the Framingham criteria for clinical HF [6]. The entry data were gathered by using an electronic data capture system; it included demographic data, etiology of HF, medical history, patient presentation, functional status, laboratory findings, and medications. The study data were collected on admission and throughout the hospital course by the expert registry team.

Definitions of the all variables registered from the patients, outcome parameters as well as the diagnosis of disease entity like cardiogenic shock, ACS infective endocarditis, and cardiomyopathies, were carried out following the American College of Cardiology (ACC) clinical data standards [7]. Valvular heart disease was defined as moderate to severe aortic and/or mitral valve disease with or without a previous history of valvular surgery, while hypertensive heart disease was defined as the presence of concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (mean thickness of the ventricular septum and LV posterior wall ≥ 12 mm) in patients with a history of or receive treatment for hypertension.

Clinical characteristics, risk factors, and previous history were determined. All included patients are symptomatic functional class (NYHA) II–IV. In the emergency department, the handling physician diagnosed HF within 30 min of admission (depending on the described criteria) by filling out a patient standard report form. HF was defined as new-onset HF or acute decompensation of chronic HF with symptoms that were sufficient to warrant hospitalization [7].

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [7] is a method that predicts mortality by classifying or weighting comorbidities like stroke, renal disease, liver disease, and cancer. It is an intensive care index utilized by health researchers to assess disease burden and considered to be an applicable prognostic indicator for mortality.

Outcomes

The status of registered patients was surveyed during hospitalization; the following information was obtained: duration of hospital stay, death, and patient destination after discharge (home or ward).

Statistical analysis

All demographic, clinical characteristics, medications, and intervention were compared using χ2 test for categorical variables and unpaired t test for continuous variables. The relationship between gender and hospital outcomes was assessed using logistic regression analysis. Cox proportional hazard modeling was employed to all-cause mortality during hospital course. Recorded data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD. Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage, and P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Adjusted outcomes were presented as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Baseline characteristics of women and men with HF, women with and without HF, and comparison of women with HFrEF and HFpEF are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. Among the 1006 patients admitted to CCU in 1 year, 345(34.2%) patients were females and 118 (34.2%) had evidence of HF, whereas 661 (65.7%) were males; 178 (26.9%) of them had HF. Regarding the HF type, in women, 73 (61.9%) had HFrEF versus 113 (63.5%) in men, P = 0.345, while 45 (38.1%) had HFpEF versus 65 (36.5%) in men, P = 0.378.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HF according to gender

| Male, n = 178 | Female, n = 118 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | 113 (63.5%) | 73 (61.9%) | 0.579 |

| Age | 59.9 ± 9 | 65.3 ± 11 | 0.0001 |

| BMI | 29.84 ± 3.2 | 31.63 ± 4 | 0.01 |

| Obesity | 81 (54.5%) | 80 (67.8%) | 0.000 |

| DM | 74 (41.6%) | 45(38.1%) | 0.628 |

| HTN | 109 (61.2%) | 67(56.8%) | 0.470 |

| Dyslipidemia | 59 (33.1%) | 47(39.8%) | 0.266 |

| Smoking | 120 (67%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.000 |

| Previous MI | 52 (29.6%) | 19 (16.1%) | 0.019 |

| Previous PCI | 34 (19.1%) | 12 (10.2%) | 0.043 |

| Prior CABG | 18 (10.1%) | 8 (6.78%) | 0.226 |

| Valve surgery | 8 (4.5%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.339 |

| Addiction | 13 (7.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 |

| STEMI | 22 (12.4%) | 16 (14%) | 0.329 |

| UA/NSTEMI | 16 (9%) | 21 (8.5%) | 0.878 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 39 (22%) | 25 (21.2%) | 0.351 |

| CHB | 3 (1.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.296 |

| AF/Flutter | 16 (8.9%) | 25 (21.2%) | 0.041 |

| IE | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.916 |

| PE | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.148 |

| Aortic dissection | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.148 |

| Cardiomyopathies | 18 (10.1%) | 23 (19.5%) | 0.011 |

| Chest pain (CP) | 35 (19.7%) | 25 (21.2%) | 0.199 |

| Orthopnea | 118 (66%) | 80 (67.8%) | 0.195 |

| PND | 40 (22.5%) | 16 (13.6%) | 0.040 |

| Palpitations | 18 (10.1%) | 14 (11.9%) | 0.191 |

| Syncope | 10 (5.62%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.024 |

| Cough | 55 (30.9%) | 38 (32.2%) | 0.704 |

| Edema | 63 (35.4%) | 38 (32.2%) | 0.847 |

| Pacemaker | 5 (2.8%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.320 |

| ICD | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.163 |

| Killip class | |||

| I | 33 (18.5%) | 11 (5.9%) | 0.023 |

| II | 8 (4.5%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.211 |

| III | 32 (18%) | 27(22.8%) | 0.119 |

| IV | 102 (57%) | 71 (60.2%) | 0.176 |

| Pricardiocentesis | 3 (1.7%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.541 |

| Thazides | 22 (12.4%) | 8 (6.8%) | 0.119 |

| Loop diuretics | 109 (61%) | 68(57.6%) | 0.535 |

| Nitrates | 103 (58%) | 67 (56.8%) | 0.853 |

| Warfarin | 63 (35.4%) | 31 (26.3%) | 0.099 |

| Clopedogril | 75 (42.1%) | 58 (49.2%) | 0.235 |

| Aldesterone antagonist | 88 (49.4%) | 50 (42.4%) | 0.233 |

| Digixon | 67 (37.6%) | 32 (27.1%) | 0.060 |

| Duration of stay | 8.71 ± 7 | 7.06 ± 5 | 0.020 |

| Mortality | 19 (10.7%) | 13(11.1%) | 0.740 |

| HFpEF | 65 (36.5%) | 45(38.1%) | 0.524 |

| Sepsis | 1 (0.6%) | 3(2.5%) | 0.254 |

| Pneumonia | 5 (2.81%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.204 |

| AKI | 23 (13%) | 12 (10.2%) | 0.336 |

| CKD/ESRD | 7 (4%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.291 |

| Resp. failure | 0(0%) | 4(3.4%) | 0.016 |

| liver failure | 1(0.6%) | 9(7.6%) | 0.000 |

| Tamponade | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.254 |

| GIT bleeding | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.148 |

| CCI | 167 (93%) | 112 (94%) | 0.692 |

| Previous MI | 54 (30.3%) | 17 (14.4%) | 0.003 |

| Previous CHF | 85 (47.8%) | 42 (35.6%) | 0.054 |

| PVD | 5 (2.8%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.296 |

| CVA/TIA | 9 (5.1%) | 10 (8.5%) | 0.167 |

| Hemiplegia | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.220 |

| COPD | 15 (8.4%) | 10 (8.5%) | 0.351 |

| VHD | 14 (7.8%) | 18(15.2%) | 0.020 |

| Peptic ulcer | 0 (0%) | 1(0.85%) | 0.163 |

| Cancer | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.163 |

| Depression | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.220 |

| Dementia | 6 (3.4%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.328 |

| Metastasis | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.148 |

| Endotracheal intubation | 27 (15.2%) | 15 (13%) | 0.553 |

| HIV | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.336 |

| Cellulitis | 1 (0.6%) | 9 (7.6%) | 0.000 |

| PCI | 20 (11.2%) | 7 (6%) | 0.021 |

| CRT | 3 (1.68%) | 2 (1.69%) | 0.329 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 28 (15.7%) | 15 (22%) | 0.471 |

| CVP | 121 (68%) | 71 (60%) | 0.168 |

| CA | 4 (2.25%) | 5 (4.24%) | 0.329 |

| DC shock | 8 (4.5%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.044 |

| Coma | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.437 |

| Fever | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.85%) | |

| Hemoptysis | 0 (0.6%) | 1 (0.85%) | |

| Lanoxin toxicisty | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.85%) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 28 (15.7%) | 15(21.7%) | 0.471 |

| Amiodarone | 17 (9.6%) | 7 (14.4%) | 0.200 |

| UFH | 62(34.8%) | 34(28.8%) | 0.279 |

| LMWH | 100(56.2%) | 79 (67%) | 0.064 |

| Lytic therapy | 45 (25.3%) | 32(27.1%) | 0.724 |

| ACEI/ARBS | 112(62.9%) | 78(66.1%) | 0.741 |

| Warfarin | 22 (12.4%) | 22(18.6%) | 0.137 |

| Beta-blockers | 61 (34.3%) | 45 (38%) | 0.794 |

| Survivors | 159 (89%) | 105 (88%) | 0.750 |

BMI body mass index, DM diabetes mellitus, HTN hypertension, STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, UA unstable angina, IE infective endocarditis, PE pulmonary embolism, PND paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, CHB complete heart block, Af atrial flutter, AF atrial fibrillation, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CA coronary angiography, CVA cerebrovascular accident

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and co morbidities of females with and without HF

| No HF, N = 277 | HF, N = 118 | P value | No HF, N = 277 | HF, N = 118 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data and etiology | Associated comorbidities | ||||||

| Age | 49.8 ± 14.5 | 60.3 ± 10.5 | 0.000 | Sepsis/shock | 5 (1.8%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.049 |

| BMI | 30.35 ± 3.1 | 31.6 ± 4 | 0.000 | Pneumonia | 5 (1.8%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.025 |

| Obesity | 150 (54.5%) | 80 (67.8%) | 0.012 | AKI | 20 (7.22%) | 12 (10.17%) | 0.114 |

| DM | 125 (41.6%) | 45 (38.1%) | 0.199 | CKD/ESRD | 6 (2.2%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.136 |

| HTN | 121 (61.2%) | 67 (56.8%) | 0.017 | Respir failure | 2 (0.72%) | 4 (3.4%) | 0.019 |

| Dyslipidemia | 86 (33.1%) | 47 (39.8%) | 0.091 | Liver failure | 1 (0.36%) | 9 (7.6%) | 0.000 |

| Smoking | 153 (67.4%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.619 | Tamponade | 9 (3.25%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.021 |

| Previous MI | 10 (3.6%) | 19 (16.1%) | 0.000 | GIT bleeding | 1 (0.36%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.047 |

| Previous PCI | 10 (3.6%) | 12 (10.2%) | 0.004 | Previous MI | 6 (2.2%) | 17 (14.4%) | 0.000 |

| Previous CABG | 3 (1.1%) | 8 (6.78%) | 0.001 | Prior CHF | 3 (1.1%) | 42 (35.6%) | 0.000 |

| Valve surgery | 0 (0%) | 6 (5.1%) | 0.000 | PVD | 3 (1.1%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.123 |

| Addiction | 3 (7.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.256 | CVA/TIA | 5 (1.8%) | 10 (8.5%) | 0.001 |

| STEMI | 55 (20%) | 16 (14%) | 0.053 | Hemiplegia | 1 (0.36%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.052 |

| UA/NSTEMI | 74 (26.7%) | 21 (8.5%) | 0.000 | COPD | 14 (5.1%) | 10 (8.5%) | 0.056 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0 (0%) | 25 (21.2%) | 0.000 | DM/end organ damage | 7 (2.5%) | 8 (6.8%) | 0.017 |

| CHB | 32 (11.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.000 | Mild liver dis | 5 (1.8%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.111 |

| AF/Flutter | 25 (9%) | 22 (18.6%) | 0.007 | Severe liver dis | 2 (0.72%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.139 |

| IE | 8 (3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.000 | peptic ulcer | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.043 |

| PE | 79 (28.5%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.000 | Cancer | 12 (4.33%) | 1 (0.85%) | 0.031 |

| Aortic dissection | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.047 | Metastasis | 8 (2.88%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.26 |

| HR (b/min) | 108.9 ± 38 | 110 ± 37 | 0.758 | Dementia | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.004 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 128.7 ± 29 | 121.54 ± 37 | 0.03 | Autoimmu. D | 13 (4.7%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.009 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.2 ± 18 | 75.3 ± 20.5 | 0.01 | CCI | 277 (100%) | 112 (94.9%) | 0.000 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 7.14 ± 6 | 7.06 ± 5 | 0.892 | Mortality (%) | 14 (5.1%) | 13 (11.1%) | 0.041 |

BMI body mass index, DM diabetes mellitus, HTN hypertension, STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, UA unstable angina, IE infective endocarditis, PE pulmonary embolism, CHB complete heart block, Af atrial flutter, AF atrial fibrillation, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CA coronary angiography, CVA cerebrovascular accident, HR heart rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, CCI Charlson comorbidity index

Table 3.

Clinical characterestics, co-morbidities and medications in HFrEF and HFpEF subgroups

| HFrEF, n = 73 | HFpEF, n = 45 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.9 ± 9 | 52.3 ± 11 | 0.0001 |

| Chest pain (CP) | 22 (30%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.001 |

| Killip class | |||

| I | 7 (9.6%) | 4 (9%) | 0.935 |

| II | 4 (5.5%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.915 |

| III | 16 (22%) | 11 (24.44%) | 0.887 |

| IV | 44 (60.3%) | 27 (60%) | 0.941 |

| Orthopnea | 50 (68.5%) | 30 (66.67%) | 0.932 |

| PND | 12 (16.4%) | 4 (9%) | 0.488 |

| Palpitations | 3 (4.12%) | 11 (24.44%) | 0.004 |

| Syncope | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.692 |

| Cough dry | 3 (4.12%) | 5 (11.11%) | 0.142 |

| Productive cough | 19 (26%) | 11 (24.44%) | 0.339 |

| Edema | 26 (35.6%) | 12 (26.67%) | 0.256 |

| Previous MI | 13 (17.8%) | 6 (13.33%) | 0.500 |

| Previous PCI | 9 (12.3%) | 3(6.67%) | 0.380 |

| Previous CABG | 7 (9.6%) | 1(2.22%) | 0.190 |

| Valve surgery | 1 (1.4%) | 5(11.11%) | 0.035 |

| STEMI | 16 (21.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.002 |

| STEMI | 16 (21.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.002 |

| UA/NSTEMI | 8 (11%) | 13(28.9%) | 0.000 |

| CHB | 1 (1.34%) | 0 (0%) | 0.436 |

| AF/flutter | 10 (13.7%) | 12 (26.6%) | 0.039 |

| IE | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.077 |

| PE | 1 (1.34%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.303 |

| Aortic dissection | 1 (1.34%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.303 |

| Hypertension | 4(5.5%) | 11(24.44%) | 0.000 |

| Prior HF | 20 ( 27%) | 8 (17.78%) | 0.000 |

| RHD | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.89%) | 0.000 |

| Pacemaker | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.108 |

| ICD | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.436 |

| CVP | 52 (71.2%) | 19 (42.2%) | 0.002 |

| Endotracheal intubation | 15 (20.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 |

| Thazides | 22 (12.4%) | 8 (6.8%) | 0.119 |

| Loop diuretics | 109 (61%) | 68 (57.6%) | 0.535 |

| Nitrates | 103 (58%) | 67 (56.78%) | 0.853 |

| Warfarin | 63 (35.4%) | 31 (26.3%) | 0.099 |

| Clopedogril | 75 (42.1%) | 58 (49.2%) | 0.235 |

| Hospital stay | 7.88 ± 5.7 | 5.73 ± 3.4 | 0.02 |

| Sepsis | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.303 |

| Pneumonia | 4 (5.5%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.575 |

| Fever | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.172 |

| Hemoptesis | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.85%) | |

| Lanoxin toxicisty |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

1 (2.22%) 1 (2.22%) |

|

| CKD/ESRD | 3 (4.12%) | 0 (0%) | 0.236 |

| Respiratory failure | 2 (2.7%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.511 |

| liver failure | 3 (4.12%) | 6 (13.3%) | 0.067 |

| Tamponade | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.303 |

| GIT bleeding | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.303 |

| CCI | 71 (97.3%) | 41 (91%) | 0.140 |

| Previous MI | 13 (17.8%) | 4 (4.44%) | 0.261 |

| AKI | 12 (16.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.016 |

| PVD | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.549 |

| CVA/TIA | 7 (9.6%) | 3 (6.7%) | 0.518 |

| Hemiplegia | 2 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.322 |

| COPD | 7 (9.6%) | 3 (6.67%) | 0.056 |

| Autoimmune | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0.046 |

| Mild liver diseases | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.436 |

| peptic ulcer | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.254 |

| Cancer | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.436 |

| Metasis | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.303 |

| Dementia | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0.336 |

| Rheumatic D | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.303 |

| HIV | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.254 |

| Cellulitis | 3 (4.12%) | 6 (13.%) | 0.067 |

| Depression | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.108 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 14 (19.2%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.007 |

| Pricardiocentesis | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.201 |

| PCI | 7 (9.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.032 |

| Coronary angiography | 5 (6.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.073 |

| Amiodarone | 17 (9.6%) | 7 (14.4%) | 0.200 |

| Unfractunated heparin | 62 (34.8%) | 34(28.8%) | 0.279 |

| LMWH | 100 (56.2%) | 79 (67%) | 0.064 |

| Lytic therapy | 45 (25.3%) | 32 (27.1%) | 0.724 |

| Mortality | 12 (16.4%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0.01 |

BMI body mass index, DM diabetes mellitus, HTN hypertension, STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, UA unstable angina, IE infective endocarditis, PE pulmonary embolism, CHB complete heart block, Af atrial flutter, AF atrial fibrillation, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CA coronary angiography, CVA cerebrovascular accident, HR heart rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure

Comparison between women and men with HF

Women with HF were older in age, more obese, and less symptomatic than men. Women had higher incidence of associated comorbidities like liver failure, respiratory failure, and cellulitis. On the contrary, the prevalence of smoking, addiction, and previous MI and PCI were lower in women than in men. Women are less liable to be repeatedly admitted to the hospital for HF and less likely to have ischemic heart disease as underling etiology of HF. However, valvular heart diseases (VHD), atrial fibrillation (AF), and cardiomyopathies were more likely to be the etiologies of their HF (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Women characteristics of HFrEF and HFpEF

Accordingly, with the lower prevalence of coronary heart disease, women were less likely to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Meanwhile, women treated with implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and/or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and cardiac pacemakers at similar frequencies as men with HF.

Compared to men, women with HF had more normal ECG: 36 (30.5%) versus 36 (20.2%) P < 0.01, more prevalence of left anterior hemiblock (LAH) 5 (4.2%) versus 2 (1.1%) P < 0.02, AF 30 (25.4%) versus 30 (16%) P < 0.04, and less likely to have LBBB 15 (12.7%) versus 60 (33.7%), P < 0.00001. Regarding echocardiographic data, women had higher EF% 47 ± 13 versus 40 ± 13, P < 0.05 and smaller LA size 18.18 ± 18 versus 22.69 ± 19, P < 0.04; nevertheless, there was no considerable difference between women and men in grades of diastolic dysfunction, severity of mitral regurg, RWMA or E/e' (P = NS), or routine laboratory workup.

There was no significant difference in medications of invasive procedures like central venous pressure (CVP), endotracheal intubation, pacemakers, or ventilation prescribed during CCU admission between women and men.

Women with HF showed shorter stay in CCU compared to men. The mortality risk during hospitalization did not differ by gender (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mortality risk in study subgroups

Comparison between women with and without HF

Comparing the 118 females with HF to 277 patients without HF (Table 2), HF females were older, more obese with higher BMI, had prevalent prior MI, with more PCI, CABG, and valve surgery. Females with HF had a higher prevalence of STEMI, NSTEMI/UA, pulmonary embolism (PE), infective endocarditis (IE), and aortic dissection and higher incidence of significant arrhythmias like AF and CHB. More hemodynamic compromise is recorded in HF female’s subgroup including higher heart rate and more hypotension. Additionally, women with HF had more frequent associated comorbidities, hepatic diseases, GIT bleeding, CVD, dementia, respiratory failure, peptic ulcer, and pneumonia. However, non-HF women had higher prevalence of cancer and autoimmune diseases.

On ECG, women with HF had higher prevalence of voltage criteria 14 (11.9%) versus 1 (0.44%), P < 0.0001, AF [30(25%) versus 11(4%)] P < 0.0001 pathologic Q wave 36 (30.5%) versus 62 (22.4%) P < 0.0001 compared to non-HF subgroup.

Regarding laboratory workup, women with HF had higher LDL level (154.15 ± 38 versus 140.88 ± 33 mg/dl, P < 0.01), FBS (209.66 ± 145 versus 149.76 ± 108 mg/dl, P < 0.001) higher A1c level 9.03 ± 2 versus 7.83 ± 3, P < 0.001, higher creatinine level (2.24 ± 3.2 versus 1.41 ± 1 mg/dl), ALT (65.7 ± 68 versus 42.41 ± 34 u, P < 0.0001) and higher INR ratio (1.54 ± 1 versus 1.21 ± 1, mg/dl, P < 0.001), lower hemoglobin (10.96 ± 3 versus12.00 ± 1, gm/dl P < 0.0001) and albumin (3.86 ± 1 versus 4.03 ± 1 mg/dl, P < 0.001.

The higher risk profile of women with HF is associated with increased mortality risk despite similar duration of hospital stay.

HFrEF and HFpEF in women

Unexpectedly, HFrEF was the commonest type of HF 73 (61.9%) versus HFpEF 45 (38.1%) in females (P < 0.001); the averaged value of EF was 33.88% in patients with reduced EF, while it was within the normal range for patients with preserved EF (61.4%) (Table 4). Comparing patients with reduced EF, to patients with preserved EF, they were significantly younger, had prevalent hypertension, more UA/NSTEMI, less STEMI and CABG, and less valve surgery. The causes of HF were ACS in a larger percentage of patients with reduced EF, where hypertensive heart disease and valvular HD were more common in those with preserved EF. Patients with reduced EF were also more likely to have frequent admission to hospital with CHF and more comorbidities like acute kidney injury (AKI) and COPD, while no difference in medications prescribed by CCU physicians between the two types. In contrast, mechanical ventilation, pacemakers, and CVP were higher in HFrEF. Clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors (PPIH) and aspirin (ASA) were more commonly prescribed to HFrEF while calcium channel blockers (CCB) were more frequently prescribed to HFpEF (Table 5).

Table 4.

ECHO findings in female HF types

| Mean | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDd (mm) | HF-REF | 39.07 ± 25 | 0.004 |

| HF-PEF | 17.53 ± 22 | ||

| LVESd (mm) | HFrEF | 23.84 ± 21 | 0.025 |

| HFpEF | 15.05 ± 20 | ||

| IVS (mm) | HFrEF | 5.42 ± 5 | 0.021 |

| HFpEF | 3.40 ± 4 | ||

| PWT (mm) | HFrEF | 5.36 ± 5 | 0.018 |

| HFpEF | 3.30 ± 4 | ||

| EF% | HFrEF | 33.88 ± 12 | 0.001 |

| HFpEF | 61.96 ± 12 | ||

| LA (mm) | HFrEF | 21.50 ± 19 | 0.012 |

| HFpEF | 12.87 ± 16 | ||

| AO (mm) | HFrEF | 28.26 ± 16.5 | 0.015 |

| HFpEF | 10.76 ± 15 | ||

| TAPSE (mm) | HFrEF | 6.84 ± 5.1 | 0.235 |

| HFpEF | 8.65 ± 4 | ||

| EPASP (mm) | HFrEF | 42.26 ± 13 | 0.503 |

| HFpEF | 40.12 ± 20 | ||

| E/A wave | HFrEF | 1.47 ± 1 | 0.409 |

| HFpEF | 1.67 ± 1 | ||

| E/e' wave | HFrEF | 18.31 ± 9.5 | 0.023 |

| HFpEF | 23.62 ± 12 | ||

| RWMA | HFrEF | 62 (85%) | 0.002 |

| HFpEF | 27 (60%) |

HFrEF heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, LVEDd left ventricular end diastolic diameter, LVESd left ventricular end systolic diameter, IVS interventricular thickness, PWT posterior wall thickness, EF% ejection fraction, LA left atrium, Ao aortic root diameter, TAPSE tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, EPASP estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure, E?A mitral flow early diastolic velocity, A mitral inflow atrial diastolic velocity, E/e mitral flow early diastolic velocityto early diastolic mitral annular velocity, RWMA regional wall motion abnormalities

Table 5.

Medications in women with HFrEF and HFpEF subgroups

| HFrEF, n = 73 | HFpEF, n = 45 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thazides | 5 (6.85%) | 3 (6.7%) | 0.969 |

| Loop diuretics | 40 (54.8%) | 28 (62.22%) | 0.428 |

| Nitrates | 39 (53.4%) | 28 (62.22%) | 0.349 |

| Warfarin | 17 (23.3%) | 14 (31.11%) | 0.348 |

| Clopidogril | 41 (56.2%) | 17 (37.8%) | 0.052 |

| CCB | 2 (2.74%) | 6 (13.33%) | 0.026 |

| Amiodarone | 10 (13.7%) | 7 (15.6%) | 0.780 |

| Unfractunated heparin | 19 (26.02%) | 15 (33.33%) | 0.395 |

| LMWH | 52 (71.23%) | 27 (60%) | 0.208 |

| Lytic therapy | 24 (32.88%) | 8 (17.8%) | 0.073 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 32 (43.8%) | 18 (40%) | 0.682 |

| Digixon | 19 (26.03%) | 13 (28.9%) | 0.734 |

| PPIH blockers | 55 (75.34%) | 42 (93.3%) | 0.013 |

| Warfarin A | 10 (13.7%) | 12 (26.7%) | 0.079 |

| ASA | 60 (82.2%) | 28 (62.22%) | 0.016 |

| Beta-blockers | 27 (37%) | 18 (40%) | 0.743 |

| ACEI | 38 (52.1%) | 22 (49%) | 0.738 |

| ARBs | 8 (11%) | 10 (22.22%) | 0.098 |

| Statin | 58 (79.5%) | 32 (71.1%) | 0.301 |

CCB calcium channel blockers, LMWH low molecular weight heparin, ASA acetyl salsylic acid, ACEI angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARBS angiotensin receptor blockers

Regarding ECG changes, women with HFpEF had higher prevalence of voltage criteria, 13 (28.9%) versus 1 (0.4%) in HFrEF, P < .00001, but lower frequency of pathologic Q and ischemic changes, 14 (31%) versus 32 (43.8%) in HFrEF, P < 0.0001.

Patients with HFpEF illustrated shorter duration of hospital stay compared with those with HFrEF. However, HFrEF showed higher risk of mortality compared to HFpEF. Mortality was significantly higher in HFrEF 12% versus 1% in HF with HFpEF.

Discussion

In the current study, the main findings are that substantial gender differences exist among Egyptian HF patients; women with HF are older, more obese, less smoker, and have more comorbidities, and HFrEF is the commonest type. Valvular heart diseases and cardiomyopathies are commonest etiology of HF. Female HF patients have similar survival during hospital course compared with men with HF.

Gender difference in clinical characteristics in CCU HF patients

The present study demonstrated gender differences in patients’ clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and short-term outcome who were admitted to CCU. Female patients were characterized by older age, higher LVEF, lower prevalence of ACS, larger incidence of valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathies in our study which is consistent with previous reports [8, 9].

The clinical manifestations of HF appeared to be less severe in women compared with men, and women had lower NYHA functional class but similar laboratory workup despite the higher and preserved LVEF%. Treatment according to latest guidelines, however, was equally or even similar to that given to women compared with men. This is in contrast to previous reports from Japanese registry [7].

Women in CCU HF patients

While previous studies of HFpEF reported that the female sex is dominant in patients with HFpEF [10], in the current study, the proportion of female to male in HFpEF was almost the same. The proportions of the females were 42% in the Japanese Diastolic Heart Failure Study (JDHF) [11] and 45% in the Japanese Cardiac Registry of Heart Failure in Cardiology (JCARE-CARD) [12], both studies enrolled Japanese patients. However, in the current registry, the proportion of HFpEF in female HF patients was similar to men: 73 (61.9%) had HFrEF versus 113 (63.5%) in men, P = 0.345 while 45(38.1%) had HFpEF in women versus 65 (36.5%) in men, P = 0.378.

The clinical characteristics of the study population were almost comparable to those of the ADHERE and OPTIMIZE-HF [6, 7]. HF patients with reduced EF were older, more obese, and more likely to have ACS. They were less likely to have a hypertension or valvular HD.

Higher prevalence of HFrEF in female patients most likely reflects the impact of age on cardiac structure and the high prevalence of coronary artery disease in this group of HF patients. HFpEF female patients had higher prevalence of hypertension and atrial fibrillation, which may possibly be a consequence as well as a causative factor for clinical presentation of such type of HF.

Additionally, respiratory failure, hepatic failure, cellulites, anemia, and hypo-albuminemia are the common comorbidities compared to men. Anemia is a strong predictor of mortality and morbidity in HF patients [5, 9], also appeared to be highly prevalent in our study, might be explained by renal dysfunction, older age, and more obesity that seems to explain the large discrepancy.

Basic HF therapy in the form of diuretics, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibition, ACE-inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers in 66% and aldosterone antagonist in 42% were similarly utilized in both women and men. These percentages are noticeably higher compared to Asian AHF registry [10] where ACEI/ARBS used in only 37% and spironolactone in 34%. Actually, the worse renal function in Asian registry (creatinine clearance 69 ml/min in this young population) could be an explanation. In accordance to our registry, the lower use of beta-blockers in 34% and 24% in Asian registry is considered and might reflect the concern of worsening HF in patients with already advanced syndrome. Digoxin and nitrates are easily available drugs traditionally but employed modestly in women with HF, it may reflect slower adoption of contemporary HF management and/or lower cost of these drugs [13].

Gender difference in short-term prognosis

One of the main findings of the present study is the similar mortality rate during CCU admission in both gender despite the difference of HF etiology, the clinical presentation, patients risk profile, and comorbidities. Our findings are confirmed by the Sakata et al. [8] in their report from the CHART-2 study, and they examined the gender difference in long-term outcome in 4736 consecutive CHF patients and found that the incidence of mortality and other events in women and men with stage C/D HF experienced 52.4 and 47.3 deaths per 1000 person-years (P = 0.225) and 58.3 and 51.3 cases of HF requiring admission per 1000 person-years (P = 0.189), respectively. They concluded that there were no gender differences in all-cause death and HF requiring admission, although the incidences of both events are much higher than those of AMI or stroke [12]

Limitations

The present study had following limitations. First, this was a single-center study involving a relatively small number of HF patients that included both gender and both types of HF (HFrEF and HFpEF) patients. Second, our registry population was limited to patients who were admitted to the CCU; HF patients who were admitted to general wards were excluded from this study. Third, this study was designed for short term outcome and had a relatively no follow-up period like those in previous reports.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although female patients had different clinical characteristics and underlying etiologies of HF which is varied from male gender, their short-term outcome and hospital mortality are similar. HF with reduced ejection fraction was present in a considerable proportion of hospitalized female patients admitted to CCU in unselected critically ill stage and associated with higher mortality risk compared to HFpEF. Given the higher risk of adverse clinical events and the lack of a satisfactory proof to guide the treatment, clinical trials are critically required to identify the effective preventive strategies for women with HF.

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviations

- CCU

Cardiac care unit

- HF

Heart failure

- HFpEF

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

Authors’ contributions

HB carried out the study design and statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. Dr NF participated in clinical and echocardiographic study and patient recruitment. Dr ME participated in patient recruitments, clinical examination, and data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the results and conclusions of this article will be available from the corresponding author on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research involved human subjects and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Menoufia University Ethical Committee with reference number 62015, Egypt. A written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hala Mahfouz Badran, Email: halamahfouz_1000@yahoo.com.

Marwa Ahmed Elgharably, Email: drmgharably@hotmail.com.

Naglaa Faheem, Email: naglaacardio@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Ko DT, Alter DA, Austin PC, et al. Life expectancy after an index hospitalization for patients with heart failure: a population based study. Am Heart J. 2008;155:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shehab A, Al-Dabbagh B, Almahmeed W, et al. Characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and heart failure in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:534. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozkurt B, Khalaf S. Heart failure in women. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2017;13(4):216–223. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-13-4-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sliwa K, Mayosi BM. Recent advances in the epidemiology, pathogenesis and prognosis of acute heart failure and cardiomyopathy in Africa. Heart. 2013;99:1317–1322. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makubi A, Hage C, Lwakatare J et al (2014) Contemporary aetiology, clinical characteristics and prognosis of adults with heart failure observed in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: the prospective Tanzania Heart Failure (TaHeF) study. Heart.:1–7 PubMed: 24319086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Mahmood SS, Wang TJ. The epidemiology of congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study perspective. Glob Heart. 2013;8(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieminen MS, Harjola VP. Definition and epidemiology of acute heart failure syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(6A):5G–10G. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon CP, Battler A, Brindis RG, Harrington RA, Krumholz HM, et al. American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2114–2130. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam CS, Carson PE, Anand IS, et al. Sex differences in clinical characteristics and outcomes in elderly patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (IPRESERVE) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:571–578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.970061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Smith G, et al. Gender, age, and heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto K, Origasa H, Hori M, et al. Investigators JDHF. Effects of carvedilol on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Japanese Diastolic Heart Failure Study (J-DHF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:110–118. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamaguchi S, Kinugawa S, Sobirin MA, et al. Investigators JCARECARD. Mode of death in patients with heart failure and reduced vs. preserved ejection fraction: report from the registry of hospitalized heart failure patients. Circ J. 2012;76:1662–1669. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nozaki A, Shirakabe A, Hata N, et al. The prognostic impact of gender in patients with acute heartfailure - an evaluation of the age of female patients with severely decompensated acute heart failure. J Cardiol. 2017;70(3):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the results and conclusions of this article will be available from the corresponding author on request.