Abstract

With rising rates of misinformation, psychotherapists are likely to encounter clients with distorted beliefs that are scientifically unsound. In situations where these beliefs are harmful (e.g., vaccination refusal, misunderstanding of sexual consent), psychotherapists may face an ethical dilemma regarding how to proceed with psychotherapy. This is especially true if such beliefs are impairing treatment progress or resulting in safety concerns for the client or society. Questions about whether and how the psychotherapist should address these distorted beliefs are therefore likely to arise. In such cases, psychotherapists are tasked with respecting the client’s autonomy, while simultaneously being of maximum benefit to the client and to society at large. Not all distorted beliefs warrant therapeutic intervention, but this judgment requires careful consideration. The current article addresses the relevant ethical considerations for navigating and addressing distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. A vignette is offered, and relevant sections of the APA’s Ethics Code are discussed, both as they pertain to this scenario and as they apply more generally to the practice of psychotherapy. The article concludes with questions for psychotherapists to consider and recommendations for how to proceed when confronted with harmful distorted beliefs.

Keywords: ethics, psychotherapy, distorted beliefs, ethical decision-making

Psychotherapists will encounter a variety of clients in their day-to-day work, some of which may hold distorted beliefs about the world. With rising rates of misinformation (e.g., Iammarino & O’Rourke, 2018) and public distrust in science (e.g., Specter, 2009), a variety of inaccurate “distorted beliefs” may increasingly find their way into the psychotherapy room. Although the psychotherapist may disagree with these beliefs, they are generally discouraged from interfering with a client’s autonomously fostered conclusions about the world (Beauchamp & Childress, 2012; O’Brien & Golding, 2003). However, there may be occasions in which the client holds beliefs that could bring harm to themselves or others. In these cases, therapeutic intervention may be warranted. At the same time, although psychotherapists are tasked with providing clients with the scientifically and clinically accurate information (American Psychological Association’s [APA] Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, 2.04, 10.01b), they must also be mindful about inserting their own beliefs about what is “right” or “wrong” when navigating such beliefs and making decisions about whether or not to address the beliefs. Therefore, when dealing with distorted beliefs, psychotherapists must consider how to balance the well-being of the client, the well-being of others, and the client’s right to autonomy in a way that is consistent with the ethics of the profession and clinical practice.

Although the literature contains some information related to the ethics of addressing harmful beliefs in psychotherapy, the majority focuses on religious beliefs (e.g., Knapp, Lemoncellio, & VandeCreek, 2010; Rosenfield, 2010). There appears to be no extant literature addressing distorted beliefs more broadly. Other distorted beliefs, such as those related to the use of vaccinations, child discipline, and firearm safety, have received less attention and may fall within a legal and ethical grey area. Like many ethical dilemmas, there is likely no single “correct” answer for psychotherapists dealing with distorted beliefs. However, the APA Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct provides several principles and standards of relevance to such instances. The current paper aims to delineate the relevant ethical issues to consider when navigating distorted beliefs in psychotherapy.

Defining Distorted Beliefs

For the purposes of this discussion, distorted beliefs can be broadly defined as a client’s inaccurate beliefs about the world or a situation that may result in harm to the client or another person. Distorted beliefs can relate to acceptable behavior, child discipline, firearm safety, education, vaccinations, and countless other topics. Although a distorted belief does not have to be contentious or political, we have found that many beliefs of this nature can evoke strong feelings in both the client and the psychotherapist. This can further complicate the ethical challenges faced by psychotherapists when navigating these beliefs in psychotherapy. It is important to note that distorted beliefs, in this case, are distinct from the concept of “irrational beliefs” or “thought distortions” that are frequently targeted in a variety of cognitive therapies.

In the current article, distorted beliefs must be both (a) objectively incorrect based on the current scientific evidence base, and (b) harmful to the client or others - given benign false beliefs do not raise the same degree of ethical concerns. Consider a client who only wears red socks because he believes it brings him good luck. Although this belief is probably objectively incorrect, the client is mostly unaffected by his belief, and, therefore, the psychotherapist has little reason to challenge the belief. However, a client who states that severe physical punishment improves their child’s behavior, a belief that is both objectively incorrect and harmful to others, will more than likely prompt the psychotherapist to address this belief in psychotherapy. Although “distorted beliefs” refer to the incorrect belief system held by the client, the actions stemming from these beliefs will often be an important factor in determining if the belief is harmful. An incorrect belief with no subsequent actions may have clinical relevance (e.g., a depressed client who incorrectly believes that everyone hates her), but such cases fall outside of the scope of this article.

Working with Distorted Beliefs: Vignette

The following vignette was created for demonstration purposes and does not represent any client or case known to the authors.

Adam is a 21-year-old male college student who has been mandated to treatment after an incident of public intoxication during a university-sponsored event. Adam reports drinking heavily on the weekends and while he does not necessarily see his drinking as a problem, he is open to talking about his drinking behavior. While exploring some of Adam ‘s drinking behavior, he reports, “It’s not like I need to drink…. It’s just a good time. I like going to parties and when everybody is drinking, getting girls is easier.” The psychotherapist asks Adam to elaborate, and Adams replies, “Sometimes they like to play hard to get, you know? But when I’m drunk that doesn ‘t bother me as much, and when they ‘re drunk, they don’t act so difficult.” At this point, the psychotherapist believes that Adam may be committing sexual assault. The psychotherapist asks Adam about consent, to which Adam replies, “I know they really want to hook up, they just act like they don’t want to.” The psychotherapist then explains to Adam the definition of consent and the potential legal consequences of his actions. Adam continues, “It’s not like I’m forcing them to do anything. I can tell that they want it too. I guess you just aren ‘t understanding. I didn ‘t come here to talk about my sex life.”

At this point, the psychotherapist has reached an ethical crossroads. The behavior described by Adam would, by many definitions, be considered sexual assault. However, Adam has made it very clear that he does not find his actions problematic and does not want the psychotherapist’s input on this specific behavior. Although the vignette focuses on sexual assault, this is only intended to serve as an example. This ethical dilemma could conceivably apply to a range of potentially harmful beliefs.

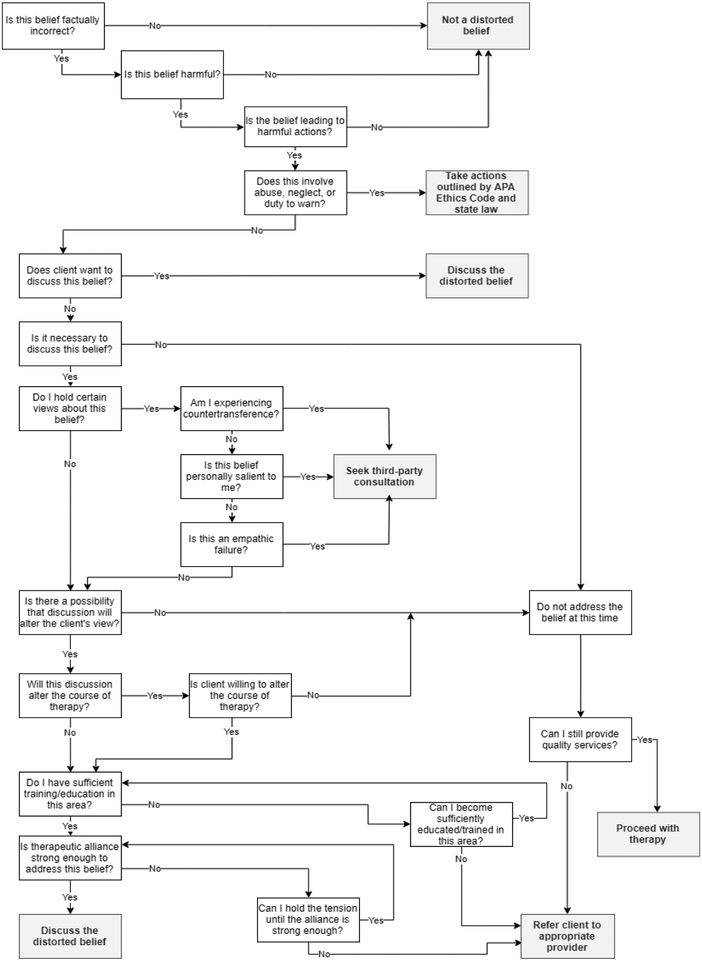

The remainder of the article introduces relevant principles and standards from the APA’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2017) - referred to as the “Ethics Code” from here forward - that one must consider when dealing with distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. The article concludes with a decision tree (Figure 1) and list of questions (Table 1) that a psychotherapist should consider when making the decision about whether and how to address a distorted belief.

Figure 1.

Decision Tree for Addressing Distorted Beliefs. We define a distorted belief as “necessary” to discuss if disregarding the belief would impede the client’s recovery or pose legitimate risk to the client or others.

Table 1.

Thirteen Questions to Consider Before Confronting a Distorted Belief in Psychotherapy

|

Note.

Questions have been adapted from Dean & Rhodes (1995).

Questions have been adapted from Rosenfield (2010).

Ethical Considerations, Principles, and Standards

There are several ethical considerations, principles, and standards relevant to navigating distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. The following discussion focuses on balancing beneficence and autonomy, competence, safety concerns, and treatment goals and informed consent, using the Ethics Code as a guide.

Balancing Beneficence and Autonomy

When met with distorted beliefs, psychotherapists face an apparent conflict between Principle A (Beneficence and Nonmaleficence) and Principle E (Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity) of the Ethics Code’s General Principles. According to Principle A (APA, 2017), “psychologists seek to safeguard the welfare and rights of those whom they interact professionally and other affected persons” (p. 3). Literature on the difference between beneficence and nonmaleficence in Principle A exists (e.g., Engelhardt 1996; Kitchener, 2000), but for the purpose of this discussion, we use “beneficence” to broadly incorporate both concepts. Beneficence is a core concept in professional psychology and is often the guiding force in many treatment decisions. So strong is the principle of beneficence that it is often argued to be an obligation (Beauchamp & Childress, 2012; Kitchener, 2000; Ross & Ross, 2002).

Beneficence is complicated by the question, “beneficial for whom?” It is not uncommon for a conflict to arise in which one outcome is most beneficial for the client and the other is most beneficial for society. Consider a client who is financially dependent on her boyfriend. She is afraid he could leave the relationship. Unbeknownst to her boyfriend, she is attempting to get pregnant by stopping her birth control without his knowledge, with the goal of securing the relationship. The client’s belief and subsequent actions benefit her, but at the expense of others (i.e., the boyfriend). There is often no rule about who should take precedence in these scenarios, so the psychotherapist must consider if they view their primary focus to be the benefit of the client or the benefit of society, which may differ based on a number of factors such as theoretical orientation.1 In the case of Adam, there are some clear benefits to addressing his distorted belief about sexual consent. Adam’s actions are harmful to the women he assaults and also potentially harmful to him. A psychotherapist prioritizing societal beneficence may find it reasonable to confront Adam about his sexual misconduct. A psychotherapist is prioritizing client beneficence may consider the adverse effects that addressing this belief will have on Adam. Being identified as a perpetrator of sexual assault may be emotionally or psychologically harmful to Adam. However, the psychotherapist may still decide that the benefits of addressing Adam’s distorted belief outweigh the costs.

According to Principle E (APA, 2017), “Psychologists respect the dignity and worth of all people, and the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination… Psychologists are aware of and respect cultural, individual, and role differences… [and] psychologists try to eliminate the effect on their work of biases based on those factors” (p. 4). Mental health care has a long and unfortunate history of professionals overriding client autonomy. Although the field has come a long way from 19th century “asylums,” psychotherapist coercion is still somewhat common in the field of mental health (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). This coercion often comes in the form of “paternalism” (or the gender-neutral “parentalism”), which can be described as intentionally overriding the client’s preferences or actions, with the justification that it is in the best interest of the client.

Although rarely malicious, it can be easy for a psychotherapist to believe that he or she knows what is best for a client. Therefore, psychotherapists should be especially mindful of parentalism. This is particularly so when the client’s belief system differs greatly from the psychotherapist’s own belief system. For example, imagine a client who keeps a loaded firearm on his nightstand “for protection against the government.” The psychotherapist may advise the client against this practice, stating “you might accidentally hurt or kill someone.” Although speaking on the grounds of beneficence, this may, in fact, be parentalism. The client is likely informed and aware of the lethality of a firearm but has proceeded with this decision anyways. The psychotherapist, without ill-intent, is subtly implying a threat (i.e., “you might hurt someone”) to change the client’s decision. Although the client’s belief about protection from the government may be unfounded, a psychotherapist prioritizing client autonomy may choose not to make a statement about the client’s decision (or may refrain from future comments) regarding his firearm on the basis of avoiding parentalism and honoring the client’s autonomy.

In the case of Adam, a psychotherapist exclusively prioritizing client autonomy may feel obligated to respect Adam’s difference in opinion regarding sexual consent and abstain from further addressing the distorted belief. Psychotherapists are responsible for recognizing the power imbalance of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., Boyd, 1996; De Varis, 1994) and refraining from allowing their own belief system to take precedence over client autonomy. Distorted beliefs that the psychotherapist views as “wrong” can easily be mistaken as “harmful.”2 As such, it is important to remember that it is not the role of the psychotherapist to align the client’s views with their own.

The conflict between beneficence and autonomy has received substantial attention in ethics literature (e.g., Engelhardt, 2001; Tjeltveit, 2006). The general consensus is that psychotherapists must be mindful of letting their ideas about what is best for the client override the client’s autonomy. This phenomena of parentalism is one of the core issues that must be examined when confronted with distorted beliefs. For example, a psychotherapist may feel that it is beneficial to dissuade a client from using physical punishment (e.g., spanking) with their children. This decision would be justified by beneficence and backed by scientific research (Ferguson, 2013; Straus, 2001). However, this could be an example of strong parentalism, in which the psychotherapist attempts to intervene despite the client’s actions being informed, voluntary, and autonomous (Beauchamp & Childress, 2012). The psychotherapist may feel that failure to intervene would contradict beneficence, whereas intervention would contradict autonomy. In the case of Adam, the psychotherapist may decide that the benefit of preventing sexual assault (Principle A) outweighs the cost of a minimal violation of autonomy (Principle E). The psychotherapist may also believe that Adam is not fully informed and that the provision of correct information regarding sexual assault may be implicated. The psychotherapist may also conclude that Adam has clearly rejected attempts at discussing this topic and decide to drop the subject out of respect for Adam’s autonomy. Although there is no clear “right” answer in these scenarios, the balance between Principle A and Principle E is a necessary consideration.

Figure 1 and Table 1 are intended to aid in resolving the tension between beneficence and autonomy. They are designed to help the psychotherapist determine (1) if the distorted belief(s) should be addressed, and (2) if the psychotherapist is the appropriate person to address this belief(s). Resolution of this tension may require consideration of the scope and magnitude of the harm being caused by the belief(s). We recommend that psychotherapists err on the side of client autonomy unless the harm posed is sufficient to require intervention in the spirit of beneficence.

Boundaries of Competence

An additional ethical issue to consider when addressing distorted beliefs is related to boundaries of competence. The APA (2017) Ethics Code states: “Psychologists provide services, teach, and conduct research with populations and in areas only within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised experience, consultation, study, or professional experience” (2.01a). When dealing with distorted beliefs, psychotherapists may feel that it is their responsibility to inform the client about how and why their belief is incorrect. At times, it may even feel even feel like a “common sense” statement. However, psychotherapists must remain aware of their own limitations and recognize when they are departing from their area of expertise. Consider the case of Adam in which the psychotherapist described the legal consequences that could befall him as a result of his sexual behaviors. Unless the psychotherapist has received special training or education on the sexual assault laws that would apply in this situation, the psychotherapist may have been operating outside the boundaries of their competence by offering this information. Providing inaccurate information may also result in unintended consequences for the client, violating the principle of beneficence. Furthermore, if the client learns that the information provided by the psychotherapist was inaccurate, it may rupture the therapeutic alliance. Incorrectly or ambiguously addressing the distorted belief may even strengthen the belief (Fryer, Harms, & Jackson, 2013).

There are several ways that a psychotherapist could choose to react when confronted with a distorted belief in psychotherapy (see Figure 1). One possibility is choosing to disregard the belief and move forward with psychotherapy as planned. If choosing to move forward with psychotherapy, one should be mindful about their own emotional reactions and belief systems. If the psychotherapist feels very strongly about the belief, failure to address it may interfere with one’s ability to competently treat the client (Standard 2.06a; APA, 2017). In contrast, the psychotherapist may decide that the distorted belief is extremely harmful and should become a focus of treatment. Psychotherapists in this situation should be cautious about shifting the focus of treatment outside of the boundaries of their competence. Adam’s psychotherapist, for example, may decide that the issue of sexual assault must be addressed as a treatment target. However, this is a significant departure from the initial focus on alcohol treatment, and the psychotherapist may consider referring Adam to another treatment provider that has received appropriate training in working with perpetrators of sexual assault. As with any treatment decision, the psychotherapist should remain mindful of how the subsequent treatment will fit into their realm of expertise.

Similar to the concerns raised about client autonomy, it can be challenging for a psychotherapist to discern how much the perceived “harm” of the client’s belief is related to the psychotherapist’s own biases. This may be especially problematic with distorted beliefs that are controversial. If a client presents distorted beliefs about a very polarizing topic, a psychotherapist with strong views on the subject may have very different ideas on how to respond to the situation than a psychotherapist who feels less strongly about the matter. In either case, it is important for a psychotherapist to consider if their beliefs will affect their competence and objectivity.

In addition, the psychotherapist must remain mindful of countertransference when addressing distorted beliefs. Countertransference, in this case, refers to the psychotherapist’s emotional reaction to the client’s beliefs. Gelso and Hayes (2001) suggest that unmanaged countertransference will likely result in damage to therapeutic process. Given the contentious nature of many distorted beliefs and the potential harm of unacknowledged countertransference, we recommend taking steps to manage countertransference when addressing distorted beliefs. Hayes and colleagues (1991) outline five important factors in managing countertransference: self-integration (i.e., stable and unified sense of identity), anxiety management, conceptualizing skills (i.e., utilizing theory and abstraction vs. fully immersing in the client’s issues), empathy, and self-insight (i.e., one’s awareness of the motivations behind their thoughts, feelings and behaviors). Self-insight seems to be an especially crucial skill for managing countertransference when addressing distorted beliefs.

A psychotherapist may mitigate some of their reaction to a belief simply by consciously understanding their reason for the reaction (Hayes et al., 1991). Understanding one’s own relationship with the distorted belief can also help the psychotherapist remain objective and make a more appropriate decision regarding their subsequent actions. There is a wealth of literature concerned with addressing countertransference in the therapeutic relationship, so we will limit our discussion on the topic to self-insight (see also Hayes, Gelso, Goldberg, & Kivlighan, 2018; Racker, 1968; and Sandler, 1976). At a minimum, psychotherapists should be conscious of countertransference when the client’s distorted belief is personally relevant to the psychotherapist. If the psychotherapist treating Adam is a survivor of sexual assault and experiences a strong reaction to his statements, it may be more appropriate to obtain outside consultation or refer Adam to a new psychotherapist (Standard 2.06b; APA, 2017; see Figure 1).

In summary, there are several components of competence that must be considered when deciding to address a distorted belief. A psychotherapist should be aware of the limits of their expertise and only provide accurate information that is within the scope of their training. Psychotherapists must also consider how addressing, or not addressing, the distorted belief will affect subsequent psychotherapy and how doing so may result in a treatment focus that is no longer within the psychotherapist’s area of expertise. Further, strong personal opinions about the client’s belief may impair the psychotherapist’s ability to competently treat the client. Lastly, we recommend that psychotherapists monitor their reaction and remain mindful of the countertransference that may arise when faced with a distorted belief.

Safety

When confronted with distorted beliefs, psychologists are responsible for recognizing if these beliefs could result in the client posing a significant threat to the safety of themselves or others (Standard 4.02; APA, 2017). The two primary circumstances relevant to this topic are situations involving “duty to warn” and abuse or neglect. When a distorted belief falls under one of these categories, psychotherapists are legally and ethically bound to initiate the appropriate procedures for addressing the concern (Standard 4.05b; APA, 2017), consistent with their state law. Determining if a situation invokes mandatory reporting can be a difficult decision and many articles have discussed guidelines for navigating such situations (e.g., Costa & Altekruse, 1994; Pietrofesa, Pietrofesa, & Pietrofesa, 1990).

When dealing with safety concerns, Rosenfield (2010) suggests starting with the question: “Is there reportable abuse or neglect?” If the answer to this question is yes, the psychotherapist is obligated to proceed with reporting procedures as mandated by their governing body (Standard 4.05b; APA, 2017) and the law.3 At times, however, distorted beliefs may be harmful but not appropriate for mandatory reporting. For example, a client who admits to falsifying documents to get her unvaccinated child into school. Laws about vaccines and vaccine exemptions vary considerably state-to-state, and some parents may seek other vaccine-hesitant individuals to inquire about “loopholes” to avoid vaccinating their children (Reich, 2018). A psychotherapist confronted with this situation may feel ethically compelled to report this information to the school. However, state law may not define this situation as one that presents “imminent harm”4 and, therefore, confidentiality must be upheld (Standard 4.01; APA, 2017). In cases where it is questionable about whether the belief has led to a reportable behavior, we suggest consulting with other professionals and relevant law before breaching confidentiality.

In the majority of cases, distorted beliefs will not trigger any mandated reporting laws. In these instances, the psychotherapist may not feel obligated to address the belief. However, in some situations, such as when the distorted belief is a direct barrier to treatment goals, it may be necessary to address the belief. In the case of Adam, we will assume that his actions are not violating the sexual consent laws of the state in which he resides. The psychotherapist may still feel that his belief about consent poses a threat to himself or women around him, and therefore feel ethically inclined to address this belief in psychotherapy. If a distorted belief appears to pose a significant threat to the safety of the client or others, a psychotherapist may wish to seek consultation from another professional about the most appropriate course of action.

Treatment Goals and Informed Consent

If the psychotherapist feels a belief should be addressed, it is important for them to distinguish between addressing the belief and shifting the focus of treatment. Psychotherapists may encounter situations where the distorted belief actually appears to be of greater clinical importance than the original referral question. Upon hearing that Adam frequently engages in predatory sexual behavior, the psychotherapist may justifiably believe that this is a more pressing issue to address than his alcohol use. If considerable time or treatment effort must be invested in addressing a belief, this should be discussed with the client before moving forward (Standard 10.01a; APA, 2017).

One suggestion for addressing the possibility of shifting treatment goals at the outset of psychotherapy would be to incorporate a general clause in the standard informed consent process. This clause could state that the psychotherapist reserves the right to digress from initial treatment goals when deemed clinically necessary and would enable the psychotherapist to flexibly address distorted beliefs should they arise during the course of treatment. Such a statement does not mean the psychotherapist should attempt to impose their desired treatment goals on the client, but rather serves to protect the psychotherapist from potential backlash if the client has a negative reaction when the distorted belief is confronted. If Adam’s psychotherapist decided to address his beliefs about sexual consent, and Adam filed a retaliatory grievance against the psychotherapist, this statement in the informed consent paperwork (e.g., “the psychotherapist reserves the right to digress from treatment goals…”) may operate as a risk management strategy and serve to protect the psychotherapist in extreme cases.

Although treatment goals may change, the informed consent process should remain a mutual and ongoing agreement between the psychotherapist and the client. The psychotherapist may choose to repeat the informed consent process after deciding that addressing the distorted belief is necessary for the continuation of treatment. When informed consent is repeated or updated, Coyne (1976) argues that clients should be fully informed of any potential outcomes of the psychotherapy they are undergoing. Dean and Rhodes (1992) discuss “broadening the contract” to include the new treatment discussion. For Adam, the psychotherapist might say, “I want to shift our treatment focus and talk a little bit about how sexual consent is defined. This conversation could bring up some uncomfortable feelings, and we can stop talking about it at any time. Is that ok with you?” Adam, conceivably, now understands that the direction of the conversation has changed and has been informed of the potential feelings that might arise from the conversation. The process of reviewing potential outcomes is particularly relevant when the distorted belief carries major implications for how a client views themselves or the world (e.g., beliefs regarding religion or the government). The psychotherapist should weigh these factors carefully and ensure that the client is fully informed about the nature and goals of the therapeutic process.

Another important factor to consider before shifting the focus of psychotherapy is the influence of the psychotherapist’s personal beliefs. Principle A states that psychologists “are alert to and guard against personal, financial, social, organizational, or political factors that might lead to misuse of their influence.” The psychotherapist must carefully consider their own personal beliefs in relation to the client’s distorted beliefs. There is evidence that people faced with contrasting beliefs overestimate the magnitude of the difference between in-group beliefs and out-group beliefs (Graham, Nosek, & Haidt, 2012; Zell, Strickhouse, Lane, & Teeter, 2016). People also tend to view out-group beliefs as more ideologically extreme (Graham et al., 2012). Psychotherapists should, therefore, be aware of such biases when examining a client’s distorted belief. In the case of Adam, the psychotherapist should consider the influence of their personal, social, and political views on sexual assault before determining if Adam’s behavior is a clinical priority. Dean and Rhodes (1992) suggest that clinicians can call attention to the differences in views and discuss them in a respectful manner. This type of discussion can be beneficial and enriching for both the client and the psychotherapist.

It is not always the case that psychotherapy must be entirely shifted to address a distorted belief. However, when the belief is gravely concerning or a direct impediment to treatment, the psychotherapist may deem it necessary to shift the focus of the treatment to addressing the belief. This decision should be considered carefully, and it is important that the client remains fully informed and involved in decisions about the nature, focus, and potential outcomes of psychotherapy throughout the process.

Additional Factors to Consider

The myriad beliefs that might be considered distorted are broad and heterogeneous. Even distorted beliefs of the same type can vary widely in intensity and outcomes. For this reason, it is nearly impossible to determine any single course of action that a psychotherapist should take to address these beliefs. To address a broad concept, we can only make broad suggestions. Each psychotherapist should apply their best clinical judgement and seek consultation when navigating ethical dilemmas in this area.

Before deciding if it is ethical to address distorted beliefs, we suggest that psychotherapists consider the questions posed in this section (see also Table 1) in combination with Figure 1. Above and beyond the normal ethical considerations of cost and benefit, these questions provide a starting point for gauging the ethical soundness of the decision which, from a risk management standpoint, can help psychotherapists readily evaluate their behavior in light of the relevant ethical principles discussed above:

What are my personal experiences with this issue/belief?

As noted previously, a psychotherapist’s competence may be jeopardized when a distorted belief becomes too personally relevant. We also acknowledge that experience or familiarity can be a valuable asset when confronting some distorted beliefs (e.g., a psychotherapist who is well-versed in the tenets of a client’s religion may have more success when addressing distorted religious belief; McMinn, 1984). Psychotherapists must examine their experiences, values, and opinions in relation to the belief and make an effort to gauge how their own experiences may be affecting their competency and their decision to address a given belief.

What assumptions do I carry about this issue/belief?

A psychotherapist engaging with a distorted belief should consider any assumptions they carry about this belief, or any assumptions they carry about the people that hold this belief. Many distorted beliefs have a strong presence in the media, resulting in exposure to stereotypes and resulting biases that psychotherapists must consider. We suggest being cautious about labeling clients based on their beliefs, especially with stereotypically-loaded terms such as “anti-vaxxer.” There is evidence that the merely labelling a group with a more negative term is sufficient to invoke differential treatment (e.g., Angermeyer & Matschinger, 2005; Gibbs & Elliot, 2015).

What is my training and education in regard to this issue/belief?

A psychotherapist is ethically obligated to seek training and education when addressing unfamiliar problems (Standard 2.01). This can become complicated with distorted beliefs because they often concern subjects with which most people feel familiar. Psychotherapists should recognize the extent of their formal training and be cautious about challenging beliefs that they do not fully understand. Conversely, if the psychotherapist is an expert on the subject, they should focus on remaining empathie and avoid immediately jumping into the “expert role” at the expense of the therapeutic relationship.

Is the therapeutic relationship strong enough to address this tension?

Therapeutic alliance is an important factor in psychotherapy outcomes (Graves et al., 2017; Krupnick et al., 2006; Lambert & Barley, 2001). Even cautious and tactful attempts at confronting a distorted belief may strain the therapeutic relationship. Before addressing a distorted belief, a psychotherapist should consider factors such as client rapport, the depth of the belief, and the client’s receptiveness. We strongly advise against challenging distorted beliefs at the expense of the therapeutic relationship as it will unlikely be successful and may even nullify future attempts at collaboration in psychotherapy.

Can I carry the tension until the alliance has become strong enough?

If a psychotherapist concludes that the therapeutic alliance is not strong enough to immediately address the belief, the psychotherapist should consider their capacity to proceed with psychotherapy. The psychotherapist’s ability to continue with psychotherapy likely varies depending on the nature and intensity of the client’s belief and the psychotherapist’s counter-beliefs. We recommend that psychotherapists monitor their client’s reactions as well as their own as the client may have brought up the distorted belief with the intention of discussing it with the psychotherapist. At times, it may be problematic to ignore the client’s belief system, in the same way that it would be problematic to intentionally ignore any other part of client diversity (Rosenfield, 2010). Other times, a psychotherapist may justifiably choose to address the distorted belief at a later time, remaining mindful of their emotional reaction to the beliefs and carefully monitoring the quality of the therapeutic relationship.

Will disregarding my negative feelings about this issue/belief jeopardize my ability to treat this client?

If choosing to disregard the distorted belief, it may be useful to consider the effect of unaddressed discord on the treatment of the client. Clients will often be aware that their distorted belief is controversial, and, as such, may be quick to notice a subsequent change in the psychotherapist’s behavior. Choosing to disregard a distorted belief, especially one that elicits negative feelings in the psychotherapist, should be predicated on the knowledge that the psychotherapist can continue showing the same level of compassion and positive regard as before the distorted belief was stated.

Is this an important issue/belief for the client, or is it an important issue/belief for me?

Distorted beliefs may sometimes appear more salient for the psychotherapist than for the client. A client’s distorted beliefs about sexual consent, although very important to the psychotherapist, may feel insignificant to the client. Balancing this issue evokes previous discussions about beneficence and client autonomy and requires careful decision-making by the psychotherapist that weighs all relevant ethical considerations. The most objective decision can be made after the psychotherapist makes an attempt to acknowledge and address bias regarding what is personally important to them. However, bias is often easier to recognize in others than in one’s self (Pronin, Lin, & Ross, 2002). To circumvent this, we recommend seeking consultation. This can help determine if the distorted belief is an important issue for the client.

Am I acting out of countertransference?

Countertransference can arise quickly when addressing distorted beliefs of a contentious nature. Therefore, psychotherapists must remain especially conscious of their internal reactions to the distorted beliefs of the client. Some skills for countertransference management, such as self-insight and empathy, may be especially useful when working with distorted beliefs. Recognizing and managing countertransference has already received considerable attention in the literature and should be consulted as needed (e.g., Hayes, Gelso, & Hummel, 2011).

Is this an empathie failure?

Empathie failures (i.e., breakdown in communication in which one party feels misunderstood or invalidated; Lemer & Jimenez, 2015) are a common and unavoidable part of relationships. Remaining vigilant for signs of empathie failure is recommended in any therapeutic setting. Notably, addressing distorted beliefs may increase risk of empathie failure. There is evidence that in-group/out-group beliefs and perceptions of normative attitudes can lead to an increased expression and tolerance of antisocial attitudes towards perceived out-group members (Crandall, Eshleman, & O’Brien, 2002; Stangor, Sechrist, & Jost, 2001). The controversial and often political nature of distorted beliefs can inadvertently lead psychotherapists towards viewing clients as out-group members, which may negatively impact the therapeutic alliance. When exploring a possible empathie failure, it is important to examine if the empathy extends beyond an intellectual level of understanding. Psychotherapists may understand the client’s perspective, but still fail to appropriately empathize (Zaki & Cikara, 2015).

Will addressing this issue significantly alter the course of psychotherapy?

It is important that the client is kept fully informed about the course of psychotherapy. Some distorted beliefs can tap deeply into foundational parts of the client’s worldview. Altering these beliefs may inadvertently create ancillary changes in the client. Before addressing distorted beliefs, one should consider what effects the change may have on the client, their treatment goals, and the psychotherapist’s competency to continue delivering the treatment.

Does the client have any desire to discuss this issue/belief?

Client interest is one of the most important considerations related to addressing distorted beliefs. If the client is open, willing, and receptive to discussing the belief and the belief has not led to harmful behaviors, many of the ethical concerns will likely dissipate. A neutral and amicable exploration of the client’s belief is likely to provide mutual benefit. If the client implicitly or explicitly expresses disinclination, the psychotherapist may use the other suggestions we have provided to determine how best to proceed.

Is it necessary to discuss this issue/belief?

The issue of necessity is unfortunately subjective and open to a variety of biases. One indisputable situation relates to reportable abuse or imminent harm (as previously discussed). The psychotherapist should also consider if the distorted belief interferes with treatment goals. In addition, the psychotherapist may consider it necessary to discuss the issue if they believes that they cannot continue treating the client with the distorted belief left unaddressed. Psychotherapists may also deem it necessary if failure to acknowledge or address the belief begins to harm the therapeutic relationship or if the desired behavioral change cannot occur without the change of the distorted belief. For example, a psychotherapist may have an easier time convincing a client to invest in a gun safe than convincing the client that he doesn’t need protection from a hostile government. Often, the question of necessity is not immediately clear and will require the psychotherapist to explore other factors to obtain more clarity.

What is the likelihood that discussing this issue/belief will change the client ‘s belief?

Distorted beliefs are often characterized as difficult to alter and there is mixed evidence regarding the malleability of deeply held beliefs (Igartua & Barrios, 2012; Wilson, Mills, Norman, & Tomlinson, 2005). As noted by Rosenfeld (2010), exploring change-resistant beliefs may introduce more risk than the potential benefits warrant. Psychotherapists may consider the length of time the beliefs have been held and how integral the beliefs are to the identity of the client. If the psychotherapists gauges that there will be little chance of any meaningful change in the client’s beliefs or behaviors, it may not be prudent to engage with the distorted belief.

What is the position of this issue/belief relative to other treatment goals?

Psychotherapists should consider how the distorted belief fits into the client’s other treatment goals. If the belief can be framed as related to the presenting problems, the client may be more receptive to discussing the belief. Another consideration is the importance of the distorted belief relative to the client’s other problems. For example, it may not be as important to address a distorted belief in an individual experiencing active psychosis.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper that addresses the ethical issues related to navigating distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. Aside from addressing harmful religious beliefs, psychotherapists have little written reference for addressing harmful beliefs that do not meet the criteria for “abuse” under mandatory reporting laws. With rising rates of misinformation, psychotherapists must be equipped with information on how to ethically address distorted beliefs in psychotherapy. We recognize that psychotherapists should not be made the arbiters of their clients’ belief systems. However, distorted beliefs can cause significant harm to clients and others around them, and as such should not be ignored in discussions ethical psychotherapy.

When the therapeutic relationship is strong, most clients will amicably discuss their beliefs. Frequently, psychotherapists will be able to discuss a distorted belief without entering an ethically uncertain situation. However, situations can arise in which psychotherapy cannot proceed without addressing the client’s distorted belief. In such cases, psychotherapists should exercise caution, so as not impose their own beliefs on the client or rupture the therapeutic relationship. As demonstrated, the Ethics Code offers general guidelines for psychotherapist behavior in these instances. Addressing distorted beliefs requires the psychotherapist to balance the principles of beneficence and client autonomy while also remaining cognizant of the boundaries of their competence (Standards 2.01, 2.06), the focus of treatment, the informed consent of the client (Standard 10.01), and the safety of the client and others (Standard 4.05b). When a distorted belief is unequivocally harmful or directly impeding treatment, the psychotherapist should consider addressing the belief in the most ethical way possible.

The current article provides a starting place for psychotherapists faced with this ethical dilemma. Similarly, this article is meant to be an introduction to the general topic of distorted beliefs. The topics presented as examples are complex and heterogeneous and are by no means covered exhaustively. We acknowledge this limitation and caution readers against viewing all of these topics as a single “type” of distorted belief. The considerations we have provided are not meant to be comprehensive, but rather a general starting point that can broadly apply to most distorted beliefs. When in doubt, we advise seeking consultation when contemplating whether and how to navigate a given client’s distorted beliefs. Future work may involve separate articles for addressing specific distorted beliefs and exploring related clinical, cultural, and ethical considerations in greater depth.

Clinical Impact Statement.

Question:

This article aims to address the ethical dilemma that occurs when working with a client who comes to psychotherapy with inaccurate, maladaptive, or potentially harmful beliefs.

Findings:

Clinicians can use this article as a starting point for guiding their own psychotherapy practice when faced with such beliefs.

Meaning:

Relevant ethics codes are reviewed and suggestions to aid in ethical decision-making are discussed.

Next Steps:

To our knowledge, this is the first paper addressing the ethical challenges that arise when addressing distorted beliefs and provides the basis for further discussions on the topic.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the NIH grant F31AA026177 to Cassandra Boness and NIH grant T32AA013526 to Kenneth Sher.

Footnotes

The theoretical orientation of the psychotherapist will likely also influence their approach to addressing distorted beliefs. Psychotherapists with cognitive-behavioral orientations may feel more inclined to address distorted beliefs. Humanistic psychotherapists may choose to discuss the utility of the belief and explore alternative ways for the client to meet their needs. Multicultural psychotherapists may view these beliefs as a part of the client’s culture and decide that they should not attempt to alter the belief. Each theoretical orientation may have a somewhat different view of what comprises a distorted belief and how to approach it. The examples listed are not meant to be prescriptive, but rather to help the reader begin to think about their own theoretical orientation and how this relates to addressing distorted beliefs.

The concept of distorted beliefs is based on scientific consensus on a given subject. However, history has repeatedly shown that expert consensus can be mistaken. Psychologists’ views on homosexuality, women in the workforce, marriage, mental disabilities, gender identity, and many other topics have changed dramatically in the last century. With that knowledge, we caution psychotherapists to consider the current Zeitgeist.

It should be noted that the client should have been informed about the limits of confidentiality during the informed consent process (Standard 4.02; APA, 2017).

Some states define vaccine refusal as medical neglect, some allow vaccine refusal, and some will base their ruling on the perceived sincerity of the refuser’s convictions (Parasidis & Opel, 2017).

References

- Angermeyer MC, & Matschinger H (2005). Labeling—stereotype—discrimination. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(5), 391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0903-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, Amended 2010 and 2017). Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp TL, & Childress JF (2012). Principles of biomedical ethics (7th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd KK (1996). Power imbalances and psychotherapy. Focus, 11(9), 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC (1976). The place of informed consent in ethical dilemmas. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44(6), 1015–1016. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.44.6.1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Eshleman A, & O’Brien L (2002). Social norms and the expression and suppression of prejudice: The struggle for internalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 359–378. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L, & Altekruse M (1994). Duty- to- Warn Guidelines for Mental Health Counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(4), 346–350. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb00947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Varis J (1994). The dynamics of power in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 31(4), 588–593. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.31.4.588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RG, & Rhodes ML (1992). Ethical-clinical tensions in clinical practice. Social Work, 37(2), 128–132. doi: 10.1093/sw/37.2.128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt HT (1996). The foundations of bioethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1136/jme.13.1.51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt HT (2001). The many faces of autonomy. Health Care Analysis, 9(3), 283–297. doi: 10.1023/A:101294973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 53(1), 196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer RG Jr, Harms P, & Jackson MO (2013). Updating beliefs with ambiguous evidence: Implications for polarization (No. wl9114). National Bureau of Economic Research; Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/wl9114 [Google Scholar]

- Gelso CJ, & Hayes JA (2001). Countertransference management. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 35(4), 418–422. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs S, & Elliott J (2015). The differential effects of labelling: How do ‘dyslexia’ and ‘reading difficulties’ affect teachers’ beliefs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(3), 323–337. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2015.1022999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Nosek BA, & Haidt J (2012). The moral stereotypes of liberals and conservatives: Exaggeration of differences across the political spectrum. PloS One, 7(12), e50092. doi: 10.1371/joumal.pone.0050092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves TA, Tabri N, Thompson- Brenner H, Franko DL, Eddy KT, Bourion-Bedes S,… & Isserlin L (2017). A meta-analysis of the relation between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50, 323–340. doi: 10.1002/eat.22672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JA, Gelso CJ, Goldberg S, & Kivlighan DM (2018). Countertransference management and effective psychotherapy: Meta-analytic findings. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 496–507. doi: 10.1037/pst0000189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JA, Gelso CJ, & Hummel AM (2011). Managing countertransference. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 88–97. doi: 10.1037/a0022182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JA, Gelso CJ, Van Wagoner SL, & Diemer RA (1991). Managing countertransference: What the experts think. Psychological Reports, 69(1), 139–148. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.1.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iammarino NK, & O’Rourke TW (2018). The Challenge of Alternative Facts and the Rise of Misinformation in the Digital Age: Responsibilities and Opportunities for Health Promotion and Education. American Journal of Health Education, 49(A), 201–205. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2018.1465864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Igartua JJ, & Barrios I (2012). Changing real-world beliefs with controversial movies: Processes and mechanisms of narrative persuasion. Journal of Communication, 62(3), 514–531. doi: 10.1111/j.l460-2466.2012.01640.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchener KS (2000). Foundations of ethical practice, research, and teaching in psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. doi: 10.4324/9780203893838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S, Lemoncelli J, & VandeCreek L (2010). Ethical responses when patients’ religious beliefs appear to harm their well-being. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(5), 405. doi: 10.1037/a0021037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krupnick JL, Sotsky SM, Elkin I, Simmens S, Moyer J, Watkins J, & Pilkonis PA (2006). The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacopsychotherapy outcome: Findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Focus, 64(2), 532–539. doi: 10.1176/foc.4.2.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, & Barley DE (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 35(4), 357–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner S, & Jimenez X (2015). Empathie failures from the patient perspective: Validation in the acute setting. Journal of Patient Experience, 2(1), 29–31. doi: 10.1177/237437431500200107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMinn MR (1984). Religious values and client-psychotherapist matching in psychotherapy. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 12(1), 24–33. doi: 10.1177/009164718401200103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien AJ, & Golding CG (2003). Coercion in mental healthcare: the principle of least coercive care. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing, 10(2), 167–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasidis E, & Opel DJ (2017). Parental refusal of childhood vaccines and medical neglect laws. American Journal of Public Health, 707(1), 68–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrofesa JJ, Pietrofesa CJ, & Pietrofesa JD (1990). The mental health counselor and “duty to warn.” Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 72(4), 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pronin E, Lin DY, & Ross L (2002). The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(3), 369–381. doi: 10.1177/0146167202286008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Racker H (1968). Transference and countertransference.London, England: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315820279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reich JA (2018). “I have to write a statement of moral conviction, can anyone help?”: Parents’ strategies for managing compulsory vaccination laws. Sociological Perspectives, 61(2), 222–239. doi: 10.1177/0731121418755113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld GW (2010). Identifying and integrating helpful and harmful religious beliefs into psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(4), 512–526. doi: 10.1037/a0021176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, & Ross WD (2002). The right and the good. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler J (1976). Countertransference and role-responsiveness. International Review of Psycho-Analysis, 3,43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Specter M (2009). Denialism: How irrational thinking harms the Planet and threatens our lives. New York, NY: Penguin, doi: 10.3201/eidl604.091710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2001). New evidence for the benefits of never spanking. Society, 38(6), 52–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02712591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stangor C, Sechrist GB, & Jost JT (2001). Social influence and intergroup beliefs: The role of perceived social consensus In Forgas JP & Williams KD (Eds.), The Sydney symposium of social psychology. Social influence: Direct and indirect processes (pp. 235–252). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tjeltveit AC (2006). To what ends? Psychotherapy goals and outcomes, the good life, and the principle of beneficence. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(2), 186–200. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.2.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K, Mills EJ, Norman G, & Tomlinson G (2005). Changing attitudes towards polio vaccination: A randomized trial of an evidence-based presentation versus a presentation from a polio survivor. Vaccine, 23(23), 3010–3015. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, & Cikara M (2015). Addressing empathie failures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(6), 471–476. doi: 10.1177/0963721415599978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zell E, Strickhouser JE, Lane TN, & Teeter SR (2016). Mars, Venus, or Earth? Sexism and the exaggeration of psychological gender differences. Sex Roles, 75(7–8), 287–300. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0622-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]