Abstract

In 2014, the International Agency for Research on Cancer judged Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) to be a probable human carcinogen. BK polyomavirus (BKPyV, a distant cousin of MCPyV) was ruled a possible carcinogen. In this review, we argue that it has recently become reasonable to view both of these viruses as known human carcinogens. In particular, several complementary lines of evidence support a causal role for BKPyV in the development of bladder carcinomas affecting organ transplant patients. The expansion of inexpensive deep sequencing has opened new approaches to investigating the important question of whether BKPyV causes urinary tract cancers in the general population.

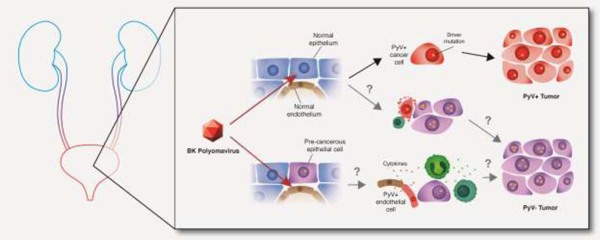

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In the late 1950s, Sarah Stewart and Bernice Eddy isolated a virus capable of causing multiple types of tumors in experimentally infected newborn mice [1]. Eddy went on to discover a different member of the “poly-oma” virus family in rhesus monkey kidney cell cultures that were used to grow inactivated poliovirus vaccine stocks. The monkey-derived polyomavirus, known as SV40, was shown to cause brain tumors when inoculated into newborn hamsters and the discovery was rightly viewed with significant alarm [2]. Fortunately, large-scale epidemiological studies have conclusively shown that people exposed to SV40-contaminated poliovirus vaccines did not suffer a detectably increased risk of developing cancer [3].

Polyomaviruses appear to co-speciate with host animal lineages [4]. The absence of SV40 genomes in modern metagenomics surveys is consistent with the idea that the monkey-derived virus is not well adapted to replication in human hosts. In contrast, a human-specific SV40 homolog, BKPyV, ubiquitously infects human populations worldwide. The primary focus of this brief review is the question of whether BKPyV causes cancer in humans.

The non-enveloped polyomavirus virion encapsidates a ~5 kb circular double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genome. The viral genome persists and replicates as an episome and integration into the host cell chromosome is not a normal feature of the viral life cycle. The genome is divided into three regions: the early region, which encodes the large and small tumor antigens (LT and sT, respectively); the late region, which encodes the virion structural proteins (VP1, VP2), and the control region, which encompasses the origin of replication and transcription regulatory elements. Eleven known human polyomavirus (HPyV) species generally establish infection at a young age, resulting in a lifelong subclinical infection in various organs. The epithelial surfaces of the bladder and kidney are the primary site of productive replication for BKPyV and its close relative JCPyV.

Polyomaviruses do not encode a DNA polymerase and are therefore wholly dependent on cellular DNA replication and DNA damage repair machinery for propagation. LT and sT are essential for unwinding the viral origin of replication and for reprogramming the cell cycle to promote DNA synthesis [5–8]. In animal model systems, expression of HPyV LT and sT, also referred to as the viral oncogenes, causes oncogenic transformation and host genome instability [9–14].

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) was discovered in cases of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), a rare but highly lethal form of skin cancer. It is now clear that in most MCC cases the MCPyV genome is no longer maintained as an episome, rather it is clonally integrated into the tumor genomic DNA. Integration is an accidental dead end for the virus but can result in persistent expression of the viral oncogenes, which is a critical factor in the ongoing development and survival of the tumor [15–18].

There is a large and conflicting body of older literature concerning the question of whether SV40 or BKPyV oncogenes can be found in human cancers (reviewed in [3,19]). A critical obstacle has been the problem of false-positive PCR and immunohistochemical detection [20]. The ubiquity of BKPyV infection and the fact that segments of the SV40 genome are in widespread use as molecular biological tools has made it particularly difficult to rule out laboratory and environmental contamination. The unprecedented resolution provided by the advent of massively parallel sequencing has partly overcome this problem. In particular, the apparent absence full-length SV40 sequences in metagenomic deep sequencing surveys is consistent with the idea that that the virus rarely or never infects humans.

Comprehensive tumor deep sequencing studies have recently begun to settle the question of how frequently BKPyV might cause cancer through an MCPyV/MCC-like mechanism. In a comprehensive deep sequencing survey of various cancer types, BKPyV was only conclusively observed integrated into the genome of one out of 413 advanced muscle-invasive bladder tumors [21–23]. The observation conclusively shows that persistent integration of BKPyV into tumor genomes is a rare event in the general population.

Epidemiological evidence for virus-induced bladder cancer

Epidemiological studies on AIDS patients and solid organ transplant recipients inform us that immunosuppressed populations are at an increased risk for developing certain forms of cancer [24–27]. For example, the observation that AIDS patients are at increased risk of developing Kaposi’s sarcoma led Chang and Moore to their discovery of the eighth human herpesvirus, KSHV [28]. Chang and Moore’s successful search for viruses in MCC tumors was likewise guided by the observation that MCC incidence is higher among immunosuppressed individuals [18,29]. Similarly, the incidence of cervical cancer, which is caused by a group of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, is also elevated among immunosuppressed individuals [25].

Several common cancer types that have not yet been associated with viral infections show significantly increased incidence in immunosuppressed populations. Most notably, organ transplant patients show a roughly 4-fold increase in risk of bladder and kidney carcinomas relative to the general population [24,25]. More recent studies investigating the relationship between kidney transplantation and the development of cancer have revealed that patients who develop BKPyV viremia or polyomavirus-associated nephropathy after transplantation have a further 4 to 11-fold increased risk of bladder cancer compared to transplant recipients without BKPyV disease [30–32]. These observations specifically implicate uncontrolled BKPyV replication in the development of bladder cancer, at least among immunosuppressed transplant recipients. Curiously, HIV+ individuals do not share this increased risk, which may reflect a difference in the biology of their immunosuppression or a yet to be discovered characteristic of BKPyV pathology in transplant recipients. “Hitchhiking” of BKPyV in the engrafted organ could be a factor.

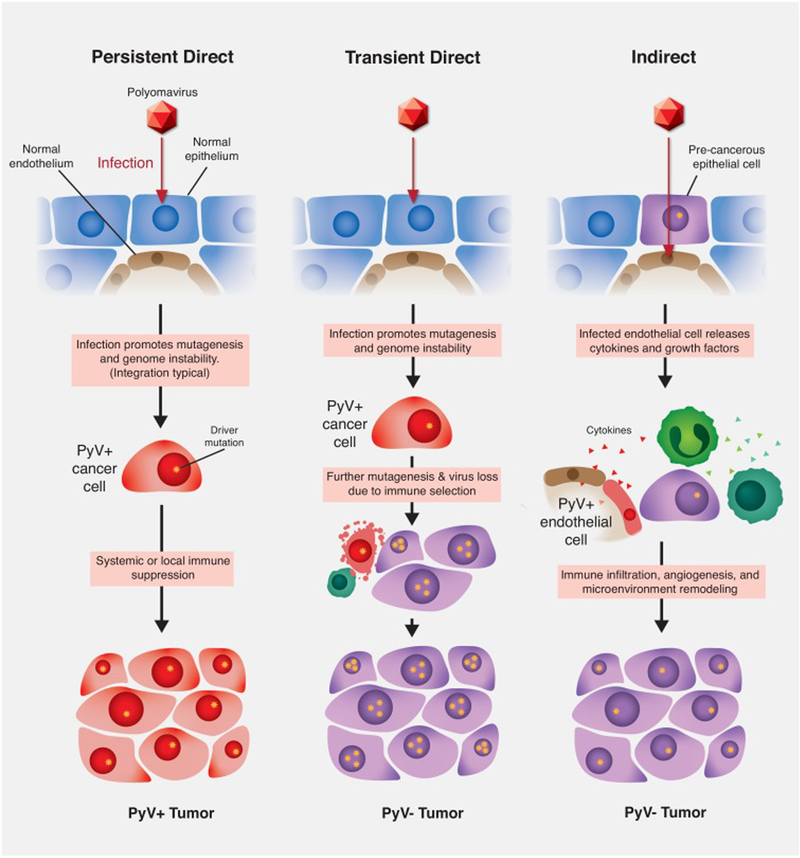

The idea that BKPyV plays a causal role in cancers of the renourinary tract has recently been confirmed by deep sequencing surveys identifying BKPyV DNA integrated into the cellular genomes of two post-transplant kidney carcinomas and three urothelial carcinomas affecting transplant patients [33–35]. The presence of BKPyV in cancers of the urinary tract is supported by a variety of other case studies (reviewed in [36]) [37–42]. Collecting duct carcinomas, also known as Bellini duct carcinomas, have emerged as a renourinary tumor type that is particularly likely to harbor BKPyV and exhibit active expression of LT [35,43–45]. As in tumor-associated MCPyV, tumor-associated BKPyV sequences generally appear to carry mutations that inactivate or remove VP1 and the helicase domain of LT. Additionally, these viruses frequently have disease-associated rearrangements in the viral control region that are known to enhance the expression of the T-antigens [38]. Together, this literature indicates that BKPyV can, at least in rare cases, cause cancers of the human urinary epithelia via a direct oncogenic mechanism in which the virus clonally persists within tumor cells (Figure 1, “Persistent Direct” column).

Figure 1.

Models of polyomavirus (PyV) contribution to carcinogenesis. Persistent direct mechanism: PyV infects an epithelial cell and, through the expression of viral oncogenes and promotion of cellular genome instability, transforms the cell. In the absence of immune-mediated tumor cell death the transformed cell grows into a PyV-positive tumor. Transient direct mechanism (also known as “hit-and-run” or “covert” pathogenesis): virus-mediated cellular genome instability promotes the accumulation of driver mutations (gold stars), eventually enabling a population of tumor cells to lose the expression of viral oncogenes. Cells expressing viral oncogenes are killed through immune surveillance leading to a PyV-negative tumor. Indirect mechanism: PyV infects an endothelial cell adjacent to a pre-malignant epithelial cell. The infected endothelial cell expresses cytokines that recruit tumor-promoting immune cells. The pre-malignant epithelial cell undergoes transformation and grows into a PyV-negative tumor.

Hit-and-run carcinogenesis

Genotoxic carcinogens, such as tobacco smoke, can cause lasting damage that permanently increases the lifetime risk of developing cancer, even long after the carcinogen has been withdrawn [46]. Similarly, examples of “covert pathogenesis” have been suggested for bacterial infections of the urinary tract where the true etiological agent is absent by the time disease symptoms manifest [47]. It has been unclear whether viruses cause cancer in humans through this type of mechanism.

Polyomaviruses share many physical and genetic properties with papillomaviruses. A subset of “high risk” HPVs belonging to the genus Alphapapillomavirus are responsible for nearly all cases of cervical, vulvar, and penile cancers as well as an increasing majority of head and neck cancers [48]. Although HPV-induced carcinomas typically harbor chromosomally integrated HPV sequences, a minority of invasive tumors carry circular (non-integrated) HPV episomes [49]. HPV-induced tumors are generally dependent on the ongoing expression of the E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which, like polyomavirus LT proteins, inactivate p53 and pRb tumor suppressor proteins [50]. A small minority of HPV-induced cervical cancers may be at least transiently independent of viral oncogene expression, possibly due to compensatory expression of cellular oncogenes and mutation of tumor suppressor genes [51].

Although the direct persistent oncogenic mechanism generally observed for high-risk HPVs is similar to that of MCPyV in MCC, work in a variety of animal model systems has demonstrated that other papillomavirus types can cause carcinomas through “hit-and-run” mechanisms in which viral DNA is lost from the nascent tumor [52–54]. Epidemiologic and mechanistic studies suggest a scenario in which human Betapapillomaviruses are an important risk factor for the early development of non-melanoma skin cancer, but viral gene expression is not required for survival of the advanced tumor [54–56]. In this scenario, viral oncogene expression promotes cell survival in the face of otherwise lethal levels of UV-mediated mutagenic damage.

A long-standing problem with the hit-and-run hypothesis has been its failure to generate readily testable predictions. The availability of high-throughput deep sequencing methods has made it increasingly possible to test two predictions of the hit-and-run hypothesis. First, it would be expected that early cancer precursor lesions would be more likely to harbor BKPyV because the pre-malignant cells have not yet acquired enough mutagenic damage to become independent of viral oncogene expression. Another prediction is that immunocompromised individuals would be less likely to exert the immunological pressure against viral proteins (thus selecting for loss of the viral DNA) and would therefore be more likely to develop BKPyV-positive bladder carcinomas. The literature cited above suggests that this latter prediction has already begun proving true.

Genotoxic effects of viral oncogenes

Beyond the inactivation of cellular tumor suppressor proteins, papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncoproteins also drive tumor evolution in part through the upregulation of the APOBEC3 family of cytosine deaminases [57–61]. APOBEC3 enzymes normally serve as antiviral defenses, and the dramatic depletion of the APOBEC3-preferred deamination target motifs in Alphapapillomavirus genomes is evidence of a long-term evolutionary conflict [62]. Mutations in the viral genome consistent with APOBEC3 deamination have been observed in cervical cancer and in precursor cervical intraepithelial neoplasias [59,63].

In healthy cells, excessive unrepaired APOBEC3 damage typically leads to p53-mediated apoptosis [64]. This supports the hypothesis that the high level of APOBEC3 damage observed in cervical carcinomas is not merely triggered by E6/E7-mediated induction of APOBEC3 expression but also depends on the ability of E6 to inactivate p53 [60,61,65–70].

Much like the papillomavirus oncoproteins, the LT proteins of several polyomaviruses have the capacity to induce APOBEC3B expression in culture models of epithelial and endothelial cell infections [71–73]. Furthermore, increased expression of APOBEC3B has been observed in nephropathic lesions co-expressing BKPyV LT [74]. Like high-risk HPV types, BKPyV genomes show a strand-biased global depletion of APOBEC3-target motifs, suggesting a long evolutionary arms race between APOBEC3 enzymes and BKPyV [73]. These analyses also highlight a curious enrichment of preferred APOBEC3 target sites (TC motifs) overlapping the VP1 major capsid protein gene. It has recently been shown that BKPyV VP1 sequences observed in patients suffering from BKPyV nephropathy carry subclonal point mutations at these sites that confer resistance to antibody-mediated neutralization [74]. Much of the variation in this region is due to C-to-G transversions at TCA trinucleotides, which then produce an equally APOBEC3-mutable TCA motif on the opposite strand [74]. This raises the possibility of reversible mutational toggling through repeated rounds of APOBEC3 damage and error-prone repair. These mutations may serve as hallmarks of disease-associated BKPyV strains.

Much like cervical and HPV-positive head and neck cancers, bladder cancers show some of the highest APOBEC3-associated mutation loads of any cancer [65]. The fact that BKPyV LT expression simultaneously induces APOBEC3B expression and prevents the p53-mediated cell death that APOBEC3 damage would generally trigger suggests a possible scenario in which the virus promotes accumulation of mutations in driver genes, eventually rendering viral gene expression dispensable and allowing loss of the virus in the face of immunological pressure.

Under this hypothesis, APOBEC3 damage could be thought of as a fossil record of the past presence of the virus (Figure 1, “Transient Direct” column). The triggers for APOBEC3 overexpression in tumors remain unclear and APOBEC3-mediated mutagenesis in xenograft model systems is puzzlingly episodic [75].

Indirect effects

Although the primary site of productive BKPyV replication is the urothelium, infection of a wide variety of other cell types, including fibroblasts, salivary epithelium, endothelium, lymphocytes, neurons, and glial cells has been documented [76–81]. In particular, infection of endothelial cells has been observed for many different species of human and non-human polyomaviruses. In immunocompromised patients, the appearance of polyomavirus-infected endothelial cells has correlated with vasculopathy and even cardiac arrest [82–85]. A recent study of BKPyV-infected primary endothelial cells revealed activation of the interferon β pathway [72]. Infected endothelial cells released the cytokine CXCL10, which has been previously identified in the urine of kidney transplant recipients as a potential biomarker of subclinical BKPyV infection [35]. Although CXCL10 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with the recruitment of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and in some cases improved outcome, other cases have shown that CXCL10 and its receptor CXCR3 can promote tumor growth and metastasis [86–88]. In some cases, tumor-associated macrophages may be recruited which can remodel of the extracellular matrix, mobilizing growth factors and promoting migration and invasion by pre-malignant and malignant cells [89,90]. BKPyV-infected endothelial cells could also have effects on angiogenesis through the release of VEGF and enhanced survival of infected cells [91]. Such early “bystander” effects could hypothetically promote tumorigenesis in a manner that would not be reflected by the presence of viral sequences in the malignant tumor (Figure 1, “Indirect” column).

Other cancers

There have been numerous reports of polyomaviruses, especially BKPyV, in cell lines and cancers from various origins (previously reviewed in [9,92]). For example, LT expression has been detected in inflammatory precursor lesions that are thought to give rise to prostate cancer [93,94]. JC polyomavirus (a close relative of BKPyV) has been inconclusively implicated in colorectal and cerebrospinal tumors and human polyomavirus 7 has been reported in thymic neoplasias [95,96]. A major confounding factor in some of these studies has been a reliance on PCR, which is susceptible to false-positive artifacts, especially in nested reactions. Without deep sequencing of the virus present in these samples and validation of distinct viral genetic features (e.g., the appearance of APOBEC3 damage or rearranged control region), it is difficult to rule out environmental contamination. The advent of inexpensive high-throughput sequencing methods should allow for a comprehensive re-evaluation of the presence of polyomaviruses in cancer and putative cancer precursor lesions.

Concluding Remarks

BKPyV can play a direct persistent causal role in bladder carcinoma and other renourinary cancers, particularly among organ transplant patients. Polyomaviruses could theoretically also act in a much wider capacity as transient direct carcinogens by promoting cell survival while also enhancing the accumulation of driver mutations in the genome of the nascent tumor, eventually facilitating escape from dependence on viral oncogene expression. In theory, polyomavirus infection of non-tumor cells, such as endothelial cells and fibroblasts, could establish a niche that promotes the survival of nascent tumors. It will be important to apply modern high-resolution approaches, such as deep sequencing, to address the open question of whether BKPyV causes a larger fraction of renourinary carcinomas or other cancers through these occult mechanisms.

A vaccine against BKPyV is currently in commercial development [97]. An approach that could conclusively test the hypothesis that uncontrolled BKPyV replication causes cancer through as-yet-undiscovered mechanisms would be to administer kidney transplant recipients a BKPyV vaccine (for the purpose of preventing BKPyV nephropathy) and then several years later retrospectively compare the incidence of cancer among vaccinees to historical baselines. This natural experiment would be akin to results showing a dramatic reduction in HPV-induced cervical pre-cancers in HPV vaccine recipients and reductions in liver cancer incidence in populations vaccinated against hepatitis B virus [98].

Highlights.

In rare cases, BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) DNA is stably integrated into the genomes of bladder carcinomas.

The risk of bladder carcinoma is elevated among transplant patients, particularly patients who develop BKPyV-mediated kidney pathology.

Bladder carcinomas affecting transplant patients are more likely to harbor BKPyV.

BKPyV activates cellular APOBEC3B, a mutagenic enzyme whose signature abundant in bladder carcinomas

Deep sequencing has opened the door to testing the hypothesis that BKPyV also causes bladder cancer through indirect or “hit-and-run” mechanisms.

A vaccine against BKPyV could reduce the risk of bladder cancer among transplant patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, with support from the Center for Cancer Research, NCI. The authors are grateful to Eric Engels for useful discussions and for critical comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eddy BE, Stewart SE: Characteristics of the SE polyoma virus. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1959, 49:1486–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eddy BE, Borman GS, Berkeley WH, Young RD: Tumors induced in hamsters by injection of rhesus monkey kidney cell extracts. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1961, 107:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvard V, Baan RA, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Straif K, IARC-Working-Group: Carcinogenicity of malaria and of some polyomaviruses. The Lancet Oncology 2012, 13:339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck CB, Doorslaer KV, Peretti A, Geoghegan EM, Tisza MJ, An P, Katz JP, Pipas JM, McBride AA, Camus C, et al. : The Ancient Evolutionary History of Polyomaviruses 2016:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ahuja D, Sáenz-Robles MT, Pipas JM: SV40 large T antigen targets multiple cellular pathways to elicit cellular transformation. Oncogene 2005, 24:7729–7745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pipas JM, Levine AJ: Role of T antigen interactions with p53 in tumorigenesis. Seminars in cancer biology 2001, 11:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris KF, Christensen JB, Imperiale MJ: BK virus large T antigen: interactions with the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressor proteins and effects on cellular growth control. Journal of virology 1996, 70:2378–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludlow JW, DeCaprio JA, Huang CM, Lee WH, Paucha E, Livingston DM: SV40 large T antigen binds preferentially to an underphosphorylated member of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product family. Cell 1989, 56:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abend JR, Jiang M, Imperiale MJ: BK virus and human cancer: innocent until proven guilty. Semin Cancer Biol 2009, 19:252–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Wang X, Diaz J, Tsang SH, Buck CB, You J: Merkel cell polyomavirus large T antigen disrupts host genomic integrity and inhibits cellular proliferation. Journal of virology 2013, 87:9173–9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwun HJ, Wendzicki JA, Shuda Y, Moore PS, Chang Y: Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen induces genome instability by E3 ubiquitin ligase targeting. Oncogene 2017, 36:6838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang M, Zhao L, Gamez M, Imperiale MJ: Roles of ATM and ATR-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic BK polyomavirus infection. PLoS Pathogens 2012, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhalen B, Justice JL, Imperiale MJ, Jiang M: Viral DNA replication-dependent DNA damage response activation during BK polyomavirus infection. Journal of Virology 2015, 89:JVI.03650–03614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spurgeon ME, Cheng J, Bronson RT, Lambert PF, DeCaprio JA: Tumorigenic activity of merkel cell polyomavirus T antigens expressed in the stratified epithelium of mice. Cancer Res 2015, 75:1068–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andres C, Belloni B, Puchta U, Sander Ca, Flaig MJ: Prevalence of MCPyV in Merkel cell carcinoma and non-MCC tumors. Journal of cutaneous pathology 2010, 37:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shuda M, Feng H, Kwun HJ, Rosen ST, Gjoerup O, Moore PS, Chang Y: T antigen mutations are a human tumor-specific signature for Merkel cell polyomavirus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105:16272–16277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassem A, Schöpflin A, Diaz C, Weyers W, Stickeler E, Werner M, Zur Hausen A: Frequent detection of merkel cell polyomavirus in human merkel cell carcinomas and identification of a unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Research 2008, 68:5009–5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS: Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2008, 319:1096–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah KV: SV40 and human cancer: a review of recent data. Int J Cancer 2007, 120:215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J, Enserink M: Virology. False positive. Science 2011, 333:1694–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantalupo PG, Katz JP, Pipas JM: Viral sequences in human cancer. Virology 2018, 513:208–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, Bellmunt J, Guo G, Cherniack AD, Hinoue T, Laird PW, Hoadley KA, Akbani R, et al. : Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cell 2017, 171:540–556 e525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.TCGA, Weinstein JN, Akbani R, Broom BM, Wang W, Verhaak RGW, McConkey D, Lerner S, Morgan M, et al. : Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 2014, 507:315–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF Jr., Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Wolfe RA, Goodrich NP, Bayakly AR, Clarke CA, et al. : Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA 2011, 306:1891–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vajdic CM, van Leeuwen MT: Cancer incidence and risk factors after solid organ transplantation. Int J Cancer 2009, 125:1747–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherston SN, Carroll RP, Harden PN, Wood KJ: Predictors of cancer risk in the long-term solid-organ transplant recipient. Transplantation 2014, 97:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM: Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2007, 370:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore PS, Chang Y: The Conundrum of Causality in Tumor Virology: The Cases of KSHV and MCV. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2014, 26:4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engels EA, Frisch M, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ, Miller RW: Merkel cell carcinoma and HIV infection. Lancet 2002, 359:497–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu S, Chaudhry MR, Berrebi AA, Papadimitriou JC, Drachenberg CB, Haririan A, Alexiev BA: Polyomavirus replication and smoking are independent risk factors for bladder cancer after renal transplantation. Transplantation 2016, 00:1–1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Gupta G, Kuppachi S, Kalil RS, Buck CB, Lynch CF, Engels EA: Treatment for presumed BK polyomavirus nephropathy and risk of urinary tract cancers among kidney transplant recipients in the United States. Am J Transplant 2018, 18:245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers R, Gohh R, Noska A: Urothelial cell carcinoma after BK polyomavirus infection in kidney transplant recipients: A cohort study of veterans. Transpl Infect Dis 2017, 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenan DJ, Mieczkowski PA, Burger-Calderon R, Singh HK, Nickeleit V: The oncogenic potential of BK-polyomavirus is linked to viral integration into the human genome. J Pathol 2015, 237:379–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenan DJ, Mieczkowski PA, Latulippe E, Cote I, Singh HK, Nickeleit V: BK Polyomavirus Genomic Integration and Large T Antigen Expression: Evolving Paradigms in Human Oncogenesis. Am J Transplant 2017, 17:1674–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sirohi D, Vaske C, Sanborn Z, Smith SC, Don MD, Lindsey KG, Federman S, Vankalakunti M, Koo J, Bose S, et al. : Polyoma virus-associated carcinomas of the urologic tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Mod Pathol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Papadimitriou JC, Randhawa P, Rinaldo CH, Drachenberg CB, Alexiev B, Hirsch HH: BK polyomavirus infection and renourinary tumorigenesis. American Journal of Transplantation 2016, 16:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller DC, Ramo M, Naegele K, Ribi S, Wetterauer C, Perrina V, Quagliata L, Vlajnic T, Ruiz C, Balitzki B, et al. : Donor-derived, metastatic urothelial cancer after kidney-transplantation associated with a potentially oncogenic BK polyomavirus. J Pathol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Anzivino E, Zingaropoli MA, Iannetta M, Pietropaolo VA, Oliva A, Iori F, Ciardi A, Rodio DM, Antonini F, Fedele CG, et al. : Archetype and Rearranged Non-coding Control Regions in Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma of Immunocompetent Individuals. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2016, 13:499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavien G, Alger J, Preece J, Alexiev BA, Alexander RB: BK Virus-Associated Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma With Prominent Micropapillary Carcinoma Component in a Cardiac Transplant Patient: Case Report and Review of Literature. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2015, 13:e397–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pino L, Rijo E, Nohales G, Frances A, Ubre A, Arango O: Bladder transitional cell carcinoma and BK virus in a young kidney transplant recipient. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society 2013, 15:E25–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumari K, Pradeep I, Kakkar A, Dinda AK, Seth A, Nayak B, Singh G: BK polyomavirus and urothelial carcinoma: Experience at a tertiary care centre in India with review of literature. Ann Diagn Pathol 2019, 40:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaur L, Gupta A, Meena P, Shingada A, Gupta P, Rana DS: Bladder Carcinoma Associated with BK Virus in a Renal Allograft Recipient. Indian J Nephrol 2019, 29:135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dao M, Pecriaux A, Bessede T, Durrbach A, Mussini C, Guettier C, Ferlicot S: BK virus-associated collecting duct carcinoma of the renal allograft in a kidney-pancreas allograft recipient. Oncotarget 2018, 9:15157–15163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dufek S, Haitel A, Muller-Sacherer T, Aufricht C: Duct Bellini carcinoma in association with BK virus nephropathy after lung transplantation . J Heart Lung Transplant 2013, 32:378–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emerson LL, Carney HM, Layfield LJ, Sherbotie JR: Collecting duct carcinoma arising in association with BK nephropathy post-transplantation in a pediatric patient. A case report with immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Pediatr Transplant 2008, 12:600–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosetti C, Gallus S, Peto R, Negri E, Talamini R, Tavani A, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C: Tobacco smoking, smoking cessation, and cumulative risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers. Am J Epidemiol 2008, 167:468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilbert NM, Lewis AL: Covert pathogenesis: Transient exposures to microbes as triggers of disease. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15:e1007586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Plummer M, et al. : Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine 2012, 30 Suppl 5:F12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pirami L, Giache V, Becciolini A: Analysis of HPV16, 18, 31, and 35 DNA in pre-invasive and invasive lesions of the uterine cervix. J Clin Pathol 1997, 50:600–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirabello L, Yeager M, Yu K, Clifford GM, Xiao Y, Zhu B, Cullen M, Boland JF, Wentzensen N, Nelson CW, et al. : HPV16 E7 Genetic Conservation Is Critical to Carcinogenesis. Cell 2017, 170:1164–1174.e1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banister CE, Liu C, Pirisi L, Creek KE, Buckhaults PJ: Identification and characterization of HPV-independent cervical cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8:13375–13386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campo MS, O’Neil BW, Barron RJ, Jarrett WF: Experimental reproduction of the papilloma-carcinoma complex of the alimentary canal in cattle. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15:1597–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasche D, Stephan S, Braspenning-Wesch I, Mikulec J, Niebler M, Grone HJ, Flechtenmacher C, Akgul B, Rosl F, Vinzon SE: The interplay of UV and cutaneous papillomavirus infection in skin cancer development. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13:e1006723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viarisio D, Muller-Decker K, Accardi R, Robitaille A, Durst M, Beer K, Jansen L, Flechtenmacher C, Bozza M, Harbottle R, et al. : Beta HPV38 oncoproteins act with a hit-and-run mechanism in ultraviolet radiation-induced skin carcinogenesis in mice. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14:e1006783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harwood CA, Toland AE, Proby CM, Euvrard S, Hofbauer GFL, Tommasino M, Bouwes Bavinck JN, KeraCon C: The pathogenesis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol 2017, 177:1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michel A, Kopp-Schneider A, Zentgraf H, Gruber AD, de Villiers EM: E6/E7 expression of human papillomavirus type 20 (HPV-20) and HPV-27 influences proliferation and differentiation of the skin in UV-irradiated SKH-hr1 transgenic mice. J Virol 2006, 80:11153–11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westrich JA, Warren CJ, Klausner MJ, Guo K, Liu CW, Santiago ML, Pyeon D: Human Papillomavirus 16 E7 Stabilizes APOBEC3A Protein by Inhibiting Cullin 2-Dependent Protein Degradation. J Virol 2018, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mori S, Takeuchi T, Ishii Y, Yugawa T, Kiyono T, Nishina H, Kukimoto I: Human papillomavirus 16 E6 up-regulates APOBEC3B via the TEAD transcription factor. Journal of Virology 2017:JVI.02413–02416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Warren CJ, Westrich JA, Doorslaer KV, Pyeon D: Roles of APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B in Human Papillomavirus Infection and Disease Progression. Viruses 2017, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Vieira VC, Leonard B, White EA, Starrett GJ, Temiz Na, Lorenz LD, Lee D, Soares MA, Lambert PF, Howley, et al. : Human papillomavirus E6 triggers upregulation of the antiviral and cancer genomic DNA deaminase APOBEC3B. mBio 2014, 5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, Boshoff C, Fenton TR: APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus-driven tumor development. Cell Reports 2014, 7:1833–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warren CJ, Van Doorslaer K, Pandey A, Espinosa JM, Pyeon D: Role of the host restriction factor APOBEC3 on papillomavirus evolution. Virus Evolution 2015, 1:vev015–vev015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hirose Y, Onuki M, Tenjimbayashi Y, Mori S, Ishii Y, Takeuchi T, Tasaka N, Satoh T, Morisada T, Iwata T, et al. : Within-Host Variations of Human Papillomavirus Reveal APOBEC-Signature Mutagenesis in the Viral Genome. J Virol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Nikkila J, Kumar R, Campbell J, Brandsma I, Pemberton HN, Wallberg F, Nagy K, Scheer I, Vertessy BG, Serebrenik AA, et al. : Elevated APOBEC3B expression drives a kataegic-like mutation signature and replication stress-related therapeutic vulnerabilities in p53-defective cells. Br J Cancer 2017, 117:113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burns MB, Temiz Na, Harris RS: Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nature genetics 2013, 45:977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gillison ML, Akagi K, Xiao W, Jiang B, Pickard RKL, Li J, Swanson BJ, Agrawal AD, Zucker M, Stache-Crain B, et al. : Human papillomavirus and the landscape of secondary genetic alterations in oral cancers. Genome Res 2019, 29:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shin S, Park HC, Kim MS, Han MR, Lee SH, Jung SH, Lee SH, Chung YJ: Whole-exome sequencing identified mutational profiles of squamous cell carcinomas of anus. Hum Pathol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Chen L, Qiu X, Zhang N, Wang Y, Wang M, Li D, Wang L, Du Y: APOBEC-mediated genomic alterations link immunity and viral infection during human papillomavirus-driven cervical carcinogenesis. Biosci Trends 2017, 11:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kondo S, Wakae K, Wakisaka N, Nakanishi Y, Ishikawa K, Komori T, Moriyama-Kita M, Endo K, Murono S, Wang Z, et al. : APOBEC3A associates with human papillomavirus genome integration in oropharyngeal cancers. Oncogene 2016, 36:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Albert Einstein College of M, Analytical Biological S, Barretos Cancer H, Baylor College of M, Beckman Research Institute of City of H, Buck Institute for Research on A, Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences C, Harvard Medical S, Helen FGCC, et al. : Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature 2017, 543:378–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Starrett GJ, Serebrenik AA, Roelofs PA, McCann JL, Verhalen B, Jarvis MC, Stewart TA, Law EK, Krupp A, Jiang M, et al. : Polyomavirus T Antigen Induces APOBEC3B Expression Using an LXCXE-Dependent and TP53-Independent Mechanism. MBio 2019, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.An P, Saenz Robles MT, Duray AM, Cantalupo PG, Pipas JM: Human polyomavirus BKV infection of endothelial cells results in interferon pathway induction and persistence. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15:e1007505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verhalen B, Starrett GJ, Harris RS, Jiang M: Functional Upregulation of the DNA Cytosine Deaminase APOBEC3B by Polyomaviruses. Journal of virology 2016, 90:6379–6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peretti A, Geoghegan EM, Pastrana DV, Smola S, Feld P, Sauter M, Lohse S, Ramesh M, Lim ES, Wang D, et al. : Characterization of BK Polyomaviruses from Kidney Transplant Recipients Suggests a Role for APOBEC3 in Driving In-Host Virus Evolution. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23:628–635 e627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petljak M, Alexandrov LB, Brammeld JS, Price S, Wedge DC, Grossmann S, Dawson KJ, Ju YS, Iorio F, Tubio JMC, et al. : Characterizing Mutational Signatures in Human Cancer Cell Lines Reveals Episodic APOBEC Mutagenesis. Cell 2019, 176:1282–1294 e1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu W, Yang R, Payne Aimee S, Schowalter Rachel M, Spurgeon Megan E, Lambert Paul F, Xu X, Buck Christopher B, You J: Identifying the Target Cells and Mechanisms of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection. Cell Host & Microbe 2016:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Burger-Calderon R, Madden V, Hallett RA, Gingerich AD, Nickeleit V, Webster-Cyriaque J: Replication of oral BK virus in human salivary gland cells. J Virol 2014, 88:559–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dorries K, Vogel E, Gunther S, Czub S: Infection of human polyomaviruses JC and BK in peripheral blood leukocytes from immunocompetent individuals. Virology 1994, 198:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van der Noordaa J, van Strien A, Sol CJ: Persistence of BK virus in human foetal pancreas cells. J Gen Virol 1986, 67 ( Pt 7):1485–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chapagain ML, Nerurkar VR: Human polyomavirus JC (JCV) infection of human B lymphocytes: a possible mechanism for JCV transmigration across the blood-brain barrier. The Journal of infectious diseases 2010, 202:184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Low J, Humes HD, Szczypka M, Imperiale M: BKV and SV40 infection of human kidney tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Virology 2004, 323:182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mishra N, Pereira M, Rhodes RH, An P, Pipas JM, Jain K, Kapoor A, Briese T, Faust PL, Lipkin WI: Identification of a novel polyomavirus in a pancreatic transplant recipient with retinal blindness and vasculitic myopathy. J Infect Dis 2014, 210:1595–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Darbinyan A, Major EO, Morgello S, Holland S, Ryschkewitsch C, Monaco MC, Naidich TP, Bederson J, Malaczynska J, Ye F, et al. : BK virus encephalopathy and sclerosing vasculopathy in a patient with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and immunodeficiency. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2016, 4:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Petrogiannis-Haliotis T, Sakoulas G, Kirby J, Koralnik IJ, Dvorak AM, Monahan-Earley R, PC DEG, U DEG, Upton M, Major EO, et al. : BK-related polyomavirus vasculopathy in a renal-transplant recipient. N Engl J Med 2001, 345:1250–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee Y, Kim YJ, Cho H: BK virus nephropathy and multiorgan involvement in a child with heart transplantation. Clin Nephrol 2019, 91:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tokunaga R, Zhang W, Naseem M, Puccini A, Berger MD, Soni S, McSkane M, Baba H, Lenz HJ: CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 axis for immune activation - A target for novel cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2018, 63:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jin WJ, Kim B, Kim D, Park Choo HY, Kim HH, Ha H, Lee ZH: NF-kappaB signaling regulates cell-autonomous regulation of CXCL10 in breast cancer 4T1 cells. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49:e295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou H, Wu J, Wang T, Zhang X, Liu D: CXCL10/CXCR3 axis promotes the invasion of gastric cancer via PI3K/AKT pathway-dependent MMPs production. Biomed Pharmacother 2016, 82:479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z: The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16:225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zeng YJ, Lai W, Wu H, Liu L, Xu HY, Wang J, Chu ZH: Neuroendocrine-like cells -derived CXCL10 and CXCL11 induce the infiltration of tumor-associated macrophage leading to the poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7:27394–27407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Catalano A, Romano M, Martinotti S, Procopio A: Enhanced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a critical role in the tumor progression potential induced by simian virus 40 large T antigen. Oncogene 2002, 21:2896–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prado JCM, Monezi TA, Amorim AT, Lino V, Paladino A, Boccardo E: Human polyomaviruses and cancer: an overview. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2018, 73:e558s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Das D, Shah RB, Imperiale MJ: Detection and expression of human BK virus sequences in neoplastic prostate tissues. Oncogene 2004, 23:7031–7046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Das D, Wojno K, Imperiale MJ: BK virus as a cofactor in the etiology of prostate cancer in its early stages. J Virol 2008, 82:2705–2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chteinberg E, Klufah F, Rennspiess D, Mannheims MF, Abdul-Hamid MA, Losen M, Keijzers M, De Baets MH, Kurz AK, Zur Hausen A: Low prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human epithelial thymic tumors. Thorac Cancer 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Rennspiess D, Pujari S, Keijzers M, Abdul-Hamid MA, Hochstenbag M, Dingemans AM, Kurz AK, Speel EJ, Haugg A, Pastrana DV, et al. : Detection of human polyomavirus 7 in human thymic epithelial tumors. J Thorac Oncol 2015, 10:360–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rodriguez RU: Prospective Grant of an Exclusive Patent License: Virus-Like Particles Vaccines Against Human Polyomaviruses, BK Virus (BKV) and JC Virus (JCV). Federal Register 2019, 84 FR 2555. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang MH, You SL, Chen CJ, Liu CJ, Lai MW, Wu TC, Wu SF, Lee CM, Yang SS, Chu HC, et al. : Long-term Effects of Hepatitis B Immunization of Infants in Preventing Liver Cancer. Gastroenterology 2016, 151:472–480 e471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]