This randomized clinical trial compares the long-term survival outcomes after repeat hepatectomy with those after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation among patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma.

Key Points

Question

What are the long-term survival outcomes after repeat hepatectomy vs percutaneous radiofrequency ablation among patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 240 patients with early-stage recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival rates after repeat hepatectomy (92.5%, 65.8%, and 43.6%, respectively) vs percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (87.5%, 52.5%, and 38.5%, respectively) were not significantly different in the intention-to-treat population.

Meaning

There did not appear to be a statistically significant difference in survival outcomes after repeat hepatectomy compared with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in patients with early-stage recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma.

Abstract

Importance

Repeat hepatectomy and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (PRFA) are most commonly used to treat early-stage recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (RHCC) after initial resection, but previous studies comparing the effectiveness of the 2 treatments have reported conflicting results.

Objective

To compare the long-term survival outcomes after repeat hepatectomy with those after PRFA among patients with early-stage RHCC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This open-label randomized clinical trial was conducted at the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital and the National Center for Liver Cancer of China. A total of 240 patients with RHCC (with a solitary nodule diameter of ≤5 cm; 3 or fewer nodules, each ≤3 cm in diameter; and no macroscopic vascular invasion or distant metastasis) were randomized 1:1 to receive repeat hepatectomy or PRFA between June 3, 2010, and January 15, 2013. The median (range) follow-up time was 44.3 (4.3-90.6) months (last follow-up, January 15, 2018). Data analysis was conducted from June 15, 2018, to September 28, 2018.

Interventions

Repeat hepatectomy (n = 120) or PRFA (n = 120).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was overall survival (OS). Secondary outcomes included repeat recurrence–free survival (rRFS), patterns of repeat recurrence, and therapeutic safety.

Results

Among the 240 randomized patients (216 men [90.0%]; median [range] age, 53.0 [24.0-59.0] years), 217 completed the trial. In the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 92.5% (95% CI, 87.9%-97.3%), 65.8% (95% CI, 57.8%-74.8%), and 43.6% (95% CI, 35.5%-53.5%), respectively, for the repeat hepatectomy group and 87.5% (95% CI, 81.8%-93.6%), 52.5% (95% CI, 44.2%-62.2%), and 38.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-48.4%), respectively, for the PRFA group (P = .17). The corresponding 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year rRFS rates were 85.0% (95% CI, 78.8%-91.6%), 52.4% (95% CI, 44.2%-62.2%), and 36.2% (95% CI, 28.5%-46.0%), respectively, for the repeat hepatectomy group and 74.2% (95% CI, 66.7%-82.4%), 41.7% (95% CI, 33.7%-51.5%), and 30.2% (95% CI, 22.9%-39.8%), respectively, for the PRFA group (P = .09). Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation was associated with a higher incidence of local repeat recurrence (37.8% vs 21.7%, P = .04) and early repeat recurrence than repeat hepatectomy (40.3% vs 23.3%, P = .04). In subgroup analyses, PRFA was associated with worse OS vs repeat hepatectomy among patients with an RHCC nodule diameter greater than 3 cm (hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.05-2.84) or an α fetoprotein level greater than 200 ng/mL (hazard ratio, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.15-2.96). Surgery had a higher complication rate than did ablation (22.4% vs 7.3%, P = .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

No statistically significant difference was observed in survival outcomes after repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA for patients with early-stage RHCC. Repeat hepatectomy may be associated with better local disease control and long-term survival in patients with an RHCC diameter greater than 3 cm or an AFP level greater than 200 ng/mL.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00822562

Introduction

Surgical resection remains the mainstay treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).1 However, the incidence of tumor recurrence can be as high as 70% at 5 years after surgery.2 Advances in postoperative surveillance have led to detection of recurrent HCC (RHCC) at an early stage when multiple treatments may still be available. Among possible treatments, salvage liver transplant has been beneficial for a limited number of patients owing to donor shortage.1 Repeat hepatectomy and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (PRFA) have been more commonly used to treat RHCC.1,3,4,5

Previous studies6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 comparing long-term survival after repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA for early-stage RHCC have reported either equivocal outcomes between the 2 procedures or favorable outcomes for one or the other (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). A previous study8 demonstrated that repeat hepatectomy was associated with better overall survival (OS) than was PRFA. However, all of the data on this topic to date have been derived from retrospective studies with inherent selection biases.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 To our knowledge, no randomized clinical trial has examined repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA.

Accordingly, the present study compared the long-term effects of repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA for patients with early-stage RHCC.

Methods

Trial Design and Participants

This open-label randomized clinical trial was carried out from June 3, 2010, to January 15, 2018, at the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital and the National Center for Liver Cancer of China. The Institutional Ethics Committee of the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital approved the study protocol (Supplement 2). The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki20 (1975) and its amendments. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines. Data analyses were conducted from June 15, 2018, to September 28, 2018.

All patients provided written informed consent prior to randomization.

Eligibility criteria included a clinical diagnosis of RHCC based on a history of partial hepatectomy for primary HCC and the criteria for diagnosis of HCC of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases21; R0 resection of the primary tumor with no macroscopic vascular invasion and extrahepatic distant metastasis8,22 and no residual disease detected within the first 2 months after the initial hepatectomy23; age of 20 to 60 years; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score24 of 0 to 1; Child-Pugh grade A liver function25; no esophageal varices and ascites; a platelet count higher than 50 × 109/L; a prothrombin time prolongation of less than 5 seconds; a solitary RHCC nodule (≤5 cm in diameter) or 3 or fewer nodules (each ≤3 cm in diameter) without any evidence of macroscopic vascular invasion or extrahepatic distant metastasis; and an RHCC located at least 1.0 cm away from the adjacent gastrointestinal tract, hepatic hilus, vena cava, or the base of the main hepatic veins, gallbladder, and diaphragm, and technically treatable by either repeat resection or percutaneous ablation.1,3,8,26 The key exclusion criteria were a history of other malignant neoplasms within the past 5 years, a history of spontaneous tumor rupture, any previous anti-RHCC treatment, severe concomitant diseases, acute or active infectious diseases, and pregnancy or breastfeeding. A complete list of the exclusion criteria is included in Supplement 1.

Randomization, Masking, and Intervention

Patients were randomized to receive repeat hepatectomy or PRFA in a 1:1 ratio. A computer-based random sequence stratified by the size (≤3 or >3 cm) and number (single or multiple) of RHCCs was generated by a staff member from the data center outside the study team before the beginning of randomization and then placed inside sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. After written informed consent was obtained from an eligible patient, a telephone call was made to the data center, and the staff member opened a sequentially placed envelope and informed the investigators of the grouping of the patient. Group allocation was unmasked to patients and physicians. Statisticians who performed the statistical analyses were masked.

The patients received open repeat hepatectomy or ultrasound-guided ablation within 1 week after randomization. Repeat hepatectomy was performed with the intention of complete removal of the macroscopic tumor with a resection margin of 0.5 cm or more.12,27 Additional nodules discovered intraoperatively were resected if the surgeons considered resection to be safe.3 Postoperative histopathological examination was routinely performed. The Edmondson-Steiner grade was used to evaluate the tumor differentiation.28 Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation was performed using the Cool-tip radiofrequency ablation system (Valleylab) to achieve a single or multiple overlapping ablations,15,29 with a goal to cover an area larger than the entire lesion plus an ablative margin of 0.5 cm or more.30,31 Dynamic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed 2 to 3 days after the ablation. If imaging studies showed radiological features of HCC that suggested incomplete ablation, an additional session of PRFA with the intention of complete ablation was performed after 3 to 5 days.18,26

The patients underwent contrast-enhanced CT or MRI and α fetoprotein (AFP) testing at 1 month after the treatment for RHCC. Additional anticancer treatments were administered to patients who had evidence of residual disease on imaging or suspected residual disease owing to an unremarkable decline of AFP levels after treatment or a positive surgical margin after repeat hepatectomy.32,33,34,35 The use of additional anticancer treatments is detailed in Supplement 1. Patients who had no residual disease did not receive adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, radioembolization, sorafenib, and interferon.32 Nucleos(t)ide analogues were used in patients infected with hepatitis B virus.36

Patients were followed up once every 2 months for 2 years after randomization and once every 3 to 6 months thereafter. At each follow-up visit, AFP and liver function tests and abdominal ultrasonography were performed. Contrast-enhanced CT scan or MRI was performed once every 4 to 6 months or earlier if clinically indicated. Repeat recurrence was diagnosed using the criteria of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases21 and was managed according to a patient’s general performance, liver function, degree of cirrhosis, and size, number of nodules, and location of the repeat recurrent disease.22,29,37

Outcomes

The primary outcome was OS, which was the interval from randomization to death from any cause, and it was censored at the date of the last follow-up when the patients were still alive. Secondary outcomes included repeat recurrence–free survival (rRFS), which was the interval from randomization to the first documented HCC repeat recurrence or death, whichever occurred earlier, and it was censored on the date of the last follow-up when the patients were still alive without repeat recurrence; the patterns of repeat recurrence, which included early or late repeat recurrence (≤12 or >12 months after the treatment for RHCC),38 type of repeat recurrence (intrahepatic, extrahepatic, or synchronous intrahepatic and extrahepatic repeat recurrences), size and site of intrahepatic repeat recurrence; and therapeutic safety. The complications were defined using the Clavien-Dindo classification and related criteria.39,40

Statistical Analysis

The superiority principle was used in sample size calculation. Using PASS software (NCSS) and a reported 5-year OS rate of 39% after PRFA and 56% after repeat hepatectomy,15,41 114 patients were required in each group to achieve a power of 80% and an α level of .05 for a 2-sided statistically significant difference. To allow for an anticipated dropout of 5% after randomization, a total of 120 patients were required per study group.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 20.0, statistical software (SPSS Inc). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using unpaired, 2-tailed, Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. Cumulative OS and rRFS were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. The 5-year OS rates were compared using the z test.42 Cox regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors of OS and rRFS. All candidate variables were set as binary mode to avoid a possible nonlinear effect. Only the variables with P < .05 in multivariable analysis were selected in the final model. If there were no potential interactions among the selected variables based on clinical judgment, the related analyses were not performed. The proportional hazard assumptions were checked by the -ln(-ln[survival]) graph. The model performance was evaluated by the concordance index (Supplement 1). Subgroup analyses on the effect of the 2 treatments were performed using independent risk factors in the multivariable analysis and variables that included sex, time to recurrence (TTR), and age, AFP levels, degree of cirrhosis, size, and number of RHCC nodules at the recurrent stage.18 Time to recurrence was defined as the interval from the initial hepatectomy to the first diagnosis of RHCC.43 Survival outcomes were analyzed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) populations. All the reported P values were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients

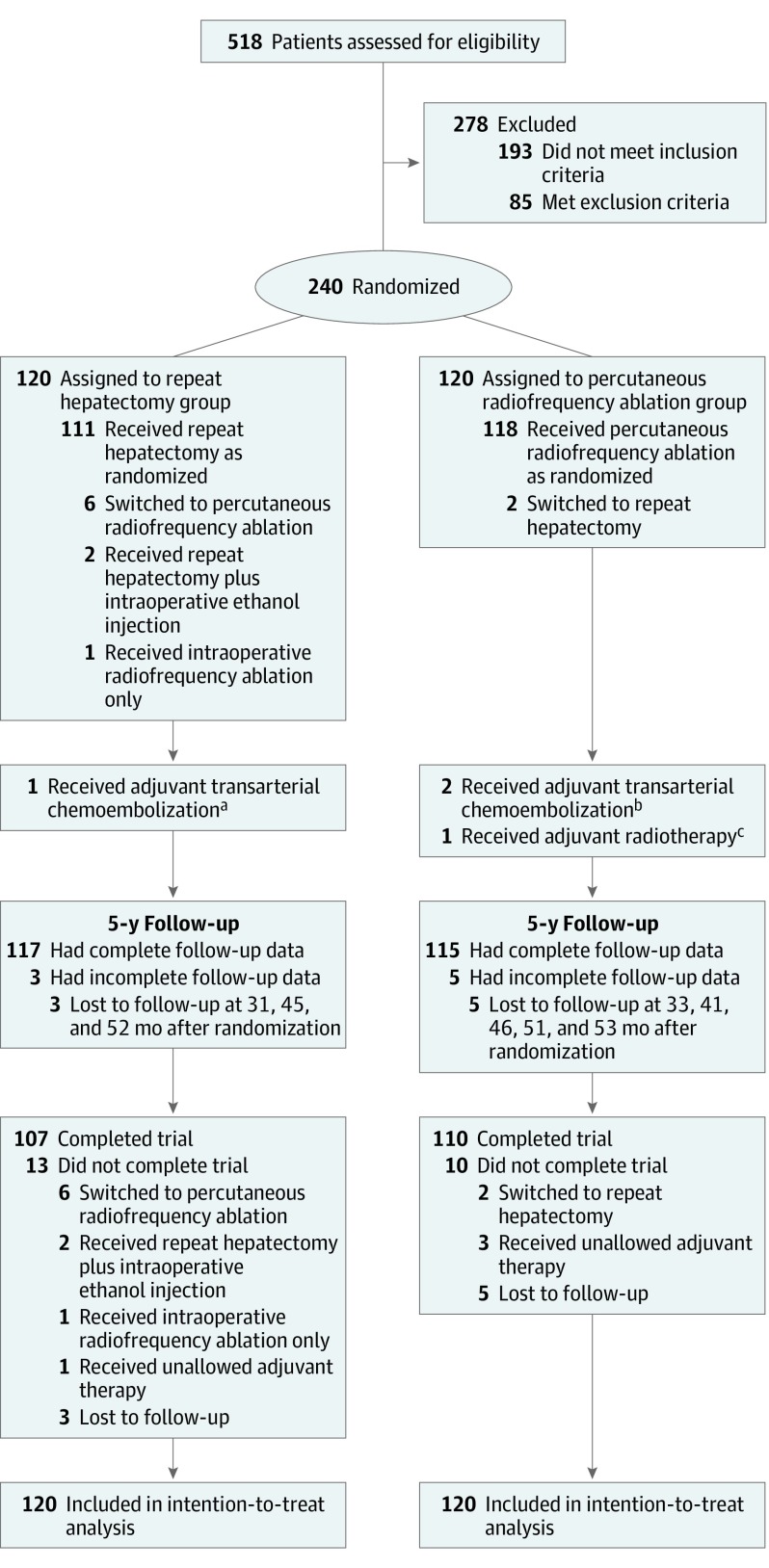

Among 518 patients assessed for eligibility between June 2010 and January 2013, 240 (216 men [90.0%]; median age, 53.0 [range, 24.0-59.0] years) were enrolled and randomized in a 1:1 ratio, with 120 patients each in the repeat hepatectomy and PRFA groups (Figure 1 and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Baseline characteristics for both groups are summarized in eTable 2 in Supplement 1.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

aReceived adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization at 45 days after repeat hepatectomy.

bReceived adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization at 38 and 43 days after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.

cReceived adjuvant radiotherapy within 32 to 67 days after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.

In the repeat hepatectomy group, 6 of 120 patients (5.0%) withdrew consent after randomization and selected PRFA, 111 of 120 (92.5%) received repeat hepatectomy only, 2 (1.7%) received repeat hepatectomy plus intratumoral ethanol injection for unresectable small nodules (≤1 cm) that were discovered intraoperatively, and 1 (0.8%) received intraoperative ablation for a solitary RHCC (3.2 cm) without repeat hepatectomy because of severe adhesions that precluded further surgical dissection. In the PRFA group, 2 of 120 patients (1.7%) withdrew consent and selected repeat hepatectomy. The remaining 118 patients (98.3%) received PRFA (Figure 1). Among all patients, 116 of 240 (48.3%) and 124 of 240 (51.7%) received surgical treatment and PRFA, respectively. The treatments of the patients are summarized in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

After the treatment for RHCC, 1 patient (0.8%) in the repeat hepatectomy group and 3 of 120 (2.5%) in the PRFA group received unallowed adjuvant treatments (Figure 1). The study was completed on January 15, 2018. The median follow-up time was 44.3 (range, 4.3-90.6) months. Three of 120 patients (2.5%) in the repeat hepatectomy group and 5 of 120 (4.2%) in the PRFA group were lost to follow-up. In the repeat hepatectomy group, 107 of 120 patients (89.1%) and 110 of 120 patients (91.7%) in the PRFA group completed the trial (Figure 1). Except for a total of 8 of 240 patients (3.3%) who were lost to follow-up in both groups, follow-up for those who were still alive was at least 5 years.

Primary Outcome

OS in the ITT Populations

Of 120 patients in the repeat hepatectomy group, 73 (60.8%) developed repeat recurrence and 67 (55.8%) died. Among those who died, 63 (94.0%) deaths were attributable to repeat recurrence, 1 had a repeat recurrence but died of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, and 3 without repeat recurrence died of other diseases. Of the remaining 53 living patients (44.2%), 9 had repeat recurrence and 44 did not. In the PRFA group, 77 of 120 patients (64.2%) had repeat recurrence, and 73 (60.8%) died; 67 deaths (91.8%) were attributed to repeat recurrence, and 6 deaths (8.2%) were attributed to other reasons without repeat recurrence. The remaining 47 of 120 patients (39.2%) survived with (n = 10) or without (n = 37) repeat recurrence.

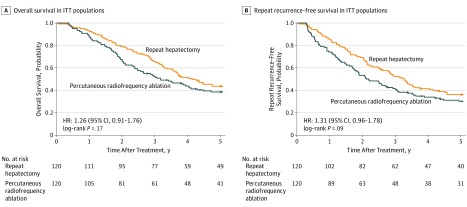

For the repeat hepatectomy and PRFA groups, the median OS was 47.1 (range, 4.3-90.6) months vs 37.5 (range, 4.5-89.0) months. The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 92.5% (95% CI, 87.9%-97.3%), 65.8% (95% CI, 57.8%-74.8%), and 43.6% (95% CI, 35.5%-53.5%), respectively, for the repeat hepatectomy group vs 87.5% (95% CI, 81.8%-93.6%), 52.5% (95% CI, 44.2%-62.2%), and 38.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-48.4%), respectively, for the PRFA group (P = .17) (Figure 2A). There was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year OS rate between the 2 groups (z = 0.793; P = .291).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plots for Overall Survival and Repeat Recurrence–Free Survival After Repeat Hepatectomy vs Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation for Recurrent Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

HR indicates hazard ratio; ITT, intention-to-treat.

Multivariable analyses demonstrated no significant difference in OS between repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA. The independent risk factors were tumor diameter greater than 5 cm (hazard ratio [HR], 1.62; 95% CI, 1.13-2.30), multinodularity (HR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.48-3.45), and the presence of microvascular invasion (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.50-3.06) at the initial stage and AFP level greater than 200 ng/mL (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.15-2.30), RHCC diameter greater than 3 cm (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.25-2.49), and TTR of 12 months or less (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.19-2.56) at the recurrent stage (Table 1 and eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Multivariable Analysis of OS and rRFS in All Patients.

| Variable | OS | rRFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Initial hepatectomy stage data | ||||

| Tumor diameter, >5 vs ≤5 cm | 1.62 (1.13-2.30) | .008 | 1.55 (1.11-2.17) | .01 |

| Multiple vs single tumorsa | 2.22 (1.48-3.45) | <.001 | 2.53 (1.72-3.72) | <.001 |

| Incomplete vs complete tumor capsule | NA | NA | 1.56 (1.12-2.17) | .009 |

| MVI present vs absent | 2.14 (1.50-3.06) | <.001 | 1.61 (1.14-2.27) | .007 |

| Recurrent stage data | ||||

| AFP level >200 vs ≤200 ng/mL | 1.63 (1.15-2.30) | .006 | 1.47 (1.06-2.05) | .021 |

| RHCC diameter >3 vs ≤3 cmb | 1.77 (1.25-2.49) | .001 | 1.51 (1.09-2.10) | .015 |

| TTR ≤12 vs >12 mo | 1.74 (1.19-2.56) | .001 | 1.97 (1.37-2.83) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha fetoprotein; HR, hazard ratio; MVI, microvascular invasion; NA, not applicable; OS, overall survival; RHCC, recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma; rRFS, repeat recurrence–free survival; TTR, time to recurrence.

Tumor nodules of 2 or more are defined as multiple tumors.

Based on pretreatment imaging studies.

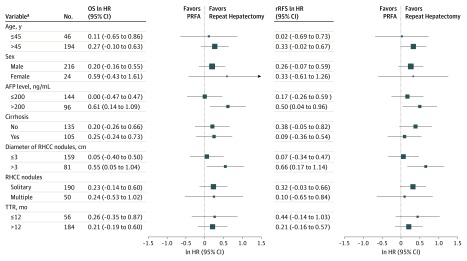

In subgroup analysis, OS was similar for the treatments among patients with an AFP level of 200 ng/mL or less or an RHCC diameter of 3 cm or less and in the subgroups of patients stratified by age, sex, cirrhosis, number of RHCC, and TTR. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation was associated with worse OS vs repeat hepatectomy in patients with AFP greater than 200 ng/mL (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.15-2.96) and RHCC diameter greater than 3 cm (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.05-2.84) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses for Comparing Repeat Hepatectomy vs Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation (PRFA) in the Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Populations.

AFP indicates α fetoprotein; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; rRFS, repeat recurrence–free survival; RHCC, recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma; and TTR, time to recurrence.

aAge, AFP levels, cirrhosis, diameter, and number of RHCC nodules were based on the data obtained at the recurrent stage. Cirrhosis, diameter, and number of RHCC nodules were based on pretreatment imaging studies.

OS in Patients Without Additional Anticancer Treatments in the ITT Populations

After treatment for RHCC, 9 of 120 patients (7.5%) in the repeat hepatectomy group (including 1 who switched to receive PRFA) and 10 of 120 (8.3%) in the PRFA group received additional anticancer treatments for radiologically identified (repeat hepatectomy, n = 7; PRFA, n = 8) or suspected (n = 2 and n = 2) residual tumor, respectively (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). The remaining 111 patients (92.5%) in the repeat hepatectomy group and 110 (91.7%) in the PRFA group did not receive any additional treatment. Baseline characteristics of patients in the 2 groups were well-balanced (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 91.9% (95% CI, 87.0%-97.1%), 66.6% (95% CI, 58.3%-76.0%), and 42.6% (95% CI, 34.2%-53.0%), respectively, for the repeat hepatectomy group vs 88.2% (95% CI, 82.4%-94.4%), 51.8% (95% CI, 43.2%-62.0%), and 39.3% (95% CI, 31.1%-49.7%), respectively, for the PRFA group (P = .24) (eFigure 2A in Supplement 1).

OS in Patients Undergoing Minor Repeat Hepatectomy vs PRFA in the ITT Populations

Ninety-nine patients did not undergo bisegmentectomy or more extensive resection in the repeat hepatectomy group (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). In these patients, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 90.9% (95% CI, 85.4%-96.8%), 66.6% (95% CI, 57.9%-76.6%), and 43.9% (95% CI, 35.1%-54.9%), respectively, vs 87.5% (95% CI, 81.8%-93.6%), 52.5% (95% CI, 44.2%-62.2%), and 38.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-48.4%), respectively (P = .20) in all 120 patients in the PRFA group (eTable 7 and eFigure 3A in Supplement 1).

OS in the PP Populations

Among 107 of 120 patients (89.2%) in the repeat hepatectomy group and 110 of 120 patients (91.7%) in the PRFA group who completed the trial (Figure 1 and eTable 8 in Supplement 1), the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates were 92.5% (95% CI, 87.7%-97.6%), 67.3% (95% CI, 59.0%-76.8%), and 44.9% (95% CI, 36.4%-55.3%), respectively, for the repeat hepatectomy group vs 88.2% (95% CI, 82.4%-94.4%), 51.8% (95% CI, 43.3%-62.0%), and 37.3% (95% CI, 29.2%-47.5%), respectively, for the PRFA group (P = .10) (eFigure 4A in Supplement 1). The 5-year OS rate between the patients in the 2 groups was not significantly different (z = 1.143; P = .25).

Secondary Outcomes

rRFS

For the repeat hepatectomy and PRFA groups, the median rRFS was 38.9 (range, 3.3-90.6) months vs 25.8 (range, 3.5-89.0) months. In the ITT populations, the corresponding rRFS rates for 1 year and 3 years in the repeat hepatectomy group were 85.0% (95% CI, 78.8%-91.6%) and 52.4% (95% CI, 44.2%-62.2%), respectively, vs 74.2% (95% CI, 66.7%-82.4%) and 41.7% (95% CI, 33.7%-51.5%), respectively, for the PRFA group. In the ITT populations, the 5-year rRFS rate was 36.2% (95% CI, 28.5%-46.0%) vs 30.2% (95% CI, 22.9%-39.8%) for all enrolled patients (P = .09) (Figure 2B), 35.5% (95% CI, 27.5%-45.7%) vs 31.2% (95% CI, 23.6%-41.3%) for patients without any additional anticancer treatment (P = .12), and 36.9% (95% CI, 28.5%-47.8%) vs 30.2% (95% CI, 22.9%-39.8%) for patients undergoing a minor repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA (P = .11) (eFigure 2B, 3B in Supplement 1). The 5-year rRFS rate was 36.4% (95% CI, 28.4%-46.8%) vs 28.2% (95% CI, 20.9%-38.0%) in the PP populations treated with repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA (P = .04) (eFigure 4B in Supplement 1). The results of the multivariable and subgroup analyses were similar to those of OS analyses (Table 1, Figure 3, and eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Patterns of Repeat Recurrence in the ITT Populations

Among 73 patients in the repeat hepatectomy and 77 patients in the PRFA group with repeat recurrence, a larger proportion of patients in the PRFA group experienced early repeat recurrence than in the repeat hepatectomy group (40% vs 23%, P = .04). The type of repeat recurrence, size of the neoplasm, and overall distribution of intrahepatic repeat recurrence were not statistically significantly different between patients in the 2 groups. However, the incidence of local repeat recurrence (located within 1 cm of the ablation zone or re-resection margin) in the patients who received PRFA was higher than that in the patients who received repeat hepatectomy (38% vs 22%, P = .04) (eTable 9 in Supplement 1). Most patients with repeat recurrence in the repeat hepatectomy (38 of 73) and PRFA groups (51 of 77) received multidisciplinary treatment. There were no statistically significant differences in the therapeutic modalities to treat repeat recurrence between the 2 groups (eTable 10 in Supplement 1).

Safety Analysis

Among 116 patients who underwent surgical treatment and 124 patients who underwent PRFA, those who underwent surgery had a higher incidence of overall complications than did those who underwent ablation (22.4% vs 7.3%, P = .001). The incidence of grade 3 or 4 complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification was 6.0% for surgical treatment vs 1.6% for PRFA (P = .09). No perioperative death occurred in this study. The median hospital stay after surgical treatment was longer than that after PRFA (8.0 [range, 5.0- 21.0] days vs 3.0 [range, 1.0-7.0] days; P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Complications After Repeat Hepatectomy and PRFA.

| Complicationa | Repeat Hepatectomy, No. (%) (n = 116)b | PRFA, No. (%) (n = 124)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Grades | Grade 3 or 4 | All Grades | Grade 3 or 4 | |

| Fever (>38.5°C, >3 d) | 19 (32.8) | 0 | 4 (22.2) | 0 |

| Ascites | 6 (10.3) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (16.7) | 0 |

| Pleural effusion | 5 (8.6) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (16.7) | 0 |

| Postoperative liver failured | 5 (8.6) | 5 (31.3) | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Wound or puncture site infection | 4 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subdiaphragmatic fluid collection | 4 (6.9) | 2 (12.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Bile leakage | 3 (5.2) | 3 (18.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage | 3 (5.2) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (5.2) | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 2 (3.4) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (50.0) |

| Atelectasis | 2 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 1 (50.0) |

| Ileus | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic subcapsular hematoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Pneumothorax | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Overall complication events | 58 (100) | 16 (100) | 18 (100) | 2 (100) |

| No. of patients | 26 (22.4)e | 7 (6.0)f | 9 (7.3)g | 2 (1.6)h |

Abbreviation: PRFA, percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.

Analyzed in patients who underwent repeat hepatectomy or PRFA.

Included 115 patients who received repeat hepatectomy (111 received repeat hepatectomy and 2 repeat hepatectomy plus intraoperative ethanol injection in the repeat hepatectomy group, and 2 underwent repeat hepatectomy after switching from the PRFA group), and 1 patient who received only intraoperative radiofrequency ablation in the repeat hepatectomy group. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.

Included 118 patients in the PRFA group and 6 switched from the repeat hepatectomy group. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.

Defined according to the 50-50 criterion on postoperative day 5 with a prothrombin time of less than 50% and a total bilirubin concentration of more than 50 μmol/L (to conver to milligrams per deciliter, multiply by 17.104).40

Five patients experienced 1 complication, 10 experienced 2 complications, and 11 experienced 3 or more complications.

One patient experienced 1 complication, 3 experienced 2 complications, and 3 experienced 3 complications.

Three patients experienced 1 complication, 3 experienced 2 complications, and 3 experienced 3 complications.

Both patients experienced 1 complication.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated no statistically significant difference in 5-year OS and rRFS among patients with early-stage RHCC undergoing repeat hepatectomy or PRFA in the ITT analysis. The incidence and severity of complications after repeat hepatectomy were greater than those after PRFA.

The difference in 5-year OS and rRFS was also not statistically significant among patients without any additional anticancer therapy after the RHCC treatment and among patients undergoing a minor repeat hepatectomy or PRFA on the ITT basis. In addition, the 5-year OS rate was not statistically significantly different after the 2 treatments in the PP populations. In subgroup analyses, differences in OS and rRFS were not significantly different between the 2 procedures among patients with or without cirrhosis and TTR less than, equal to, or greater than 12 months. A short TTR is usually associated with an increased chance of RHCC originating from intrahepatic metastasis that is associated with a poor survival after repeat hepatectomy,8,43 and cirrhosis is usually associated with an increased surgical risk. In the present study, complications were more common and severe after surgery than after PRFA. These data demonstrate that PRFA is effective and safe for patients with early-stage RHCC.

The results suggest that repeat hepatectomy is likely to be associated with better local disease control than PRFA. Patients with repeat recurrence in the repeat hepatectomy group had a significantly lower incidence of local or early repeat recurrence than did those in the PRFA group. Subgroup analyses demonstrated better OS and rRFS after repeat hepatectomy than after PRFA among patients with an RHCC diameter greater than 3 cm. Studies of primary HCC have demonstrated that the chance of complete ablation decreases as the tumor increases in size.21,44 In this study, PRFA was more likely to result in local residual disease than was repeat hepatectomy, particularly when the RHCC diameter was greater than 3 cm (eTable 11 in Supplement 1). In addition, compared with ablation, repeat hepatectomy was associated with an improved rRFS in the PP populations, and better OS and rRFS among patients with elevated AFP levels, which are associated with aggressiveness of HCC,8 although this result came from an unplanned subgroup analysis. These data support repeat hepatectomy as an appropriate treatment in selected patients.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, this was a single-institution study. As an open-label study, residual bias may exist in the study design. In addition, the results of the subgroup analyses need to be further validated because of the lack of adjustments for multiple testing, which may increase the type I error and lead to false-positive results. To our knowledge, previous studies have not reported the prognostic difference between repeat hepatectomy vs ablation in patients infected with the hepatitis B (HBV) or hepatitis C virus, respectively,6,7,10,11,12 and most patients had HBV infection in this study. Therefore, whether our results can be applied to HCC with etiologies other than HBV infection remains to be determined.

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that repeat hepatectomy is associated with better local disease control and OS than PRFA in patients with an RHCC diameter greater than 3 cm or an AFP level greater than 200 ng/mL. However, the data did not show that repeat hepatectomy was superior to PRFA for the treatment of early-stage RHCC. Further studies are needed on the prognostic differences after laparoscopic repeat hepatectomy vs PRFA and a more effective multidisciplinary treatment strategy for RHCC.45,46

eAppendix 1. Complete List of the Exclusion Criteria

eAppendix 2. Additional Anti-Cancer Treatment for Residual Tumor and Adjuvant Therapy After Re-hepatectomy or PRFA

eAppendix 3. The Strategies of Building the Multivariable Models

eTable 1. Survival Outcomes Following Re-Hepatectomy Vs PRFA for RHCC in Medical Literature

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 3. Treatment for RHCC in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 4. Univariable Analysis of OS and rRFS in all Participants (continued)

eTable 5. Additional Anti-Cancer Treatments in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Without Additional Anti-Cancer Treatments in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 7. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Minor Re-Hepatectomy Vs PRFA in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 8. Baseline Characteristics of the Per-Protocol Populations

eTable 9. Patterns of Re-Recurrence in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 10. Management of Re-Recurrence in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 11. Intrahepatic Sites of Residual Tumor Following Re-Hepatectomy and PRFA

eFigure 1. Exclusion of Patients

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plots for OS and rRFS for Patients Without Additional Anti-Cancer Treatments in the ITT Population

eFigure 3. Kaplan-Meier Plots for OS and rRFS for Patients Undergoing Minor Re-Hepatectomy Vs PRFA in the ITT Populations

eFigure 4. Kaplan-Meier Plots for OS and rRFS for Patients in the PP Populations

eReferences.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol. 2012;56(suppl 1):S75-S87. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1907-1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer . EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):908-943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Sui C, Li B, et al. Repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a local experience and a systematic review. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:55-56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavriilidis P, Askari A, Azoulay D. Survival following redo hepatectomy vs radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2017;19(1):3-9. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Peng Z, Xiao H, et al. Combined radiofrequency ablation and ethanol injection versus repeat hepatectomy for elderly patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after initial hepatic surgery. Int J Hyperthermia. 2018;34(7):1029-1037. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2017.1387941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song KD, Lim HK, Rhim H, et al. Repeated hepatic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection: a propensity score matching study. Radiology. 2015;275(2):599-608. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14141568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang K, Liu G, Li J, et al. Early intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy treated with re-hepatectomy, ablation or chemoembolization: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(2):236-242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisele RM, Chopra SS, Lock JF, Glanemann M. Treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma confined to the liver with repeated resection and radiofrequency ablation: a single center experience. Technol Health Care. 2013;21(1):9-18. doi: 10.3233/THC-120705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan AC, Poon RT, Cheung TT, et al. Survival analysis of re-resection versus radiofrequency ablation for intrahepatic recurrence after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2012;36(1):151-156. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1323-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho CM, Lee PH, Shau WY, Ho MC, Wu YM, Hu RH. Survival in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after primary hepatectomy: comparative effectiveness of treatment modalities. Surgery. 2012;151(5):700-709. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umeda Y, Matsuda H, Sadamori H, Matsukawa H, Yagi T, Fujiwara T. A prognostic model and treatment strategy for intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. World J Surg. 2011;35(1):170-177. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0794-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawano Y, Sasaki A, Kai S, et al. Prognosis of patients with intrahepatic recurrence after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(2):174-179. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueno M, Uchiyama K, Ozawa S, et al. Prognostic impact of treatment modalities on patients with single nodular recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Today. 2009;39(8):675-681. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3942-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang HH, Chen MS, Peng ZW, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus repeat hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(12):3484-3493. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0076-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah SA, Cleary SP, Wei AC, et al. Recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Surgery. 2007;141(3):330-339. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tralhão JG, Dagher I, Lino T, Roudié J, Franco D. Treatment of tumour recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Analysis of 97 consecutive patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(6):746-751. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Chen Y, Li Q, Ma D, Shen B, Peng C. Radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection for intrahepatic hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence: a meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2015;195(1):166-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erridge S, Pucher PH, Markar SR, et al. Meta-analysis of determinants of survival following treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2017;104(11):1433-1442. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruix J, Sherman M; Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases . Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1208-1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang T, Lu JH, Lau WY, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion does not influence recurrence-free and overall survivals after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a Propensity Score Matching Analysis. J Hepatol. 2016;64(3):583-593. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma ZC, Huang LW, Tang ZY, et al. [Three-grade criteria of curative resection for primary liver cancer]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2004;26(1):33-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60(8):646-649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng K, Yan J, Li X, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57(4):794-802. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagasue N, Uchida M, Makino Y, et al. Incidence and factors associated with intrahepatic recurrence following resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(2):488-494. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90724-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edmondson HA, Steiner PE. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;7(3):462-503. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang SJ, Hu P, Wang N, et al. Thermal ablation versus repeated hepatic resection for recurrent intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3596-3602. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3035-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg SN, Grassi CJ, Cardella JF, et al. ; Society of Interventional Radiology Technology Assessment Committee; International Working Group on Image-Guided Tumor Ablation . Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria. Radiology. 2005;235(3):728-739. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353042205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, et al. ; International Working Group on Image-guided Tumor Ablation; Interventional Oncology Sans Frontières Expert Panel; Technology Assessment Committee of the Society of Interventional Radiology; Standard of Practice Committee of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe . Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria–a 10-year update. Radiology. 2014;273(1):241-260. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182-236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugo H, Ishizaki Y, Yoshimoto J, Imamura H, Kawasaki S. Salvage hepatectomy for local recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after ablation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(7):2238-2245. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2220-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi D, Lim HK, Kim MJ, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: percutaneous radiofrequency ablation after hepatectomy. Radiology. 2004;230(1):135-141. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301021182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. Treatment outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma using chemoembolization in combination with other therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32(8):594-606. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45(2):507-539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang J, Yan L, Cheng Z, et al. A randomized trial comparing radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for HCC conforming to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg. 2010;252(6):903-912. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181efc656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah SA, Greig PD, Gallinger S, et al. Factors associated with early recurrence after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(2):275-283. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205-213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balzan S, Belghiti J, Farges O, et al. The “50-50 criteria” on postoperative day 5: an accurate predictor of liver failure and death after hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2005;242(6):824-828. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189131.90876.9e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kokudo N. Selection criteria for repeat hepatectomy in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2003;238(5):703-710. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094549.11754.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosseinipour MC, Bisson GP, Miyahara S, et al. ; Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5274 (REMEMBER) Study Team . Empirical tuberculosis therapy versus isoniazid in adult outpatients with advanced HIV initiating antiretroviral therapy (REMEMBER): a multicountry open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1198-1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00546-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi M, Shimizu T, Hirokawa F, et al. Clinicopathological risk factors for recurrence within one year after initial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Surg. 2011;77(5):572-578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, Li C, Wen T, Peng W, Yan L, Yang J. Outcomes of salvage liver transplantation and re-resection/radiofrequency ablation for intrahepatic recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a new surgical strategy based on recurrence pattern. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(2):502-514. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4861-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machairas N, Papaconstantinou D, Stamopoulos P, et al. The emerging role of laparoscopic liver resection in the treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(5):3181-3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wakabayashi T, Felli E, Memeo R, et al. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic repeat liver resection after open liver resection: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(7):2083-2092. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06754-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Complete List of the Exclusion Criteria

eAppendix 2. Additional Anti-Cancer Treatment for Residual Tumor and Adjuvant Therapy After Re-hepatectomy or PRFA

eAppendix 3. The Strategies of Building the Multivariable Models

eTable 1. Survival Outcomes Following Re-Hepatectomy Vs PRFA for RHCC in Medical Literature

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 3. Treatment for RHCC in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 4. Univariable Analysis of OS and rRFS in all Participants (continued)

eTable 5. Additional Anti-Cancer Treatments in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Without Additional Anti-Cancer Treatments in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 7. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Minor Re-Hepatectomy Vs PRFA in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 8. Baseline Characteristics of the Per-Protocol Populations

eTable 9. Patterns of Re-Recurrence in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 10. Management of Re-Recurrence in the Intention-to-Treat Populations

eTable 11. Intrahepatic Sites of Residual Tumor Following Re-Hepatectomy and PRFA

eFigure 1. Exclusion of Patients

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plots for OS and rRFS for Patients Without Additional Anti-Cancer Treatments in the ITT Population

eFigure 3. Kaplan-Meier Plots for OS and rRFS for Patients Undergoing Minor Re-Hepatectomy Vs PRFA in the ITT Populations

eFigure 4. Kaplan-Meier Plots for OS and rRFS for Patients in the PP Populations

eReferences.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement