Key Points

Question

Is receipt of a housing voucher associated with subsequent rates of hospital utilization and spending in long-term follow-up?

Findings

In this exploratory analysis that included 4072 adults and 9118 children with a median 11 years of follow-up, adults randomized to receive a housing voucher, compared with a control group, did not experience significant differences in outcomes (rates of hospitalization, 14.0 vs 14.7 per 100 person-years; hospital days, 62.8 vs 67.0 per 100 person-years; yearly spending, $2075 vs $1977). Children whose families received a housing voucher compared with a control group without a voucher had significantly lower rates of hospitalization (6.3 vs 7.3 per 100 person-years) and yearly inpatient spending ($633 vs $785), without a significant difference in hospital days (25.7 vs 28.8 per 100 person-years).

Meaning

Receipt of a housing voucher was not associated with significant differences in hospital use or spending among adults; however, children whose family received a voucher had significantly lower rates of hospitalization and inpatient spending during long-term follow-up.

Abstract

Importance

Although neighborhoods are thought to be an important health determinant, evidence for the relationship between neighborhood poverty and health care use is limited, as prior studies have largely used observational data without an experimental design.

Objective

To examine whether housing policies that reduce exposure to high-poverty neighborhoods were associated with differences in long-term hospital use among adults and children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Exploratory analysis of the Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program, a randomized social experiment conducted in 5 US cities. From 1994 to 1998, 4604 families in public housing were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: a control condition, a traditional Section 8 voucher toward rental costs in the private market, or a voucher that could only be used in low-poverty neighborhoods. Participants were linked to all-payer hospital discharge data (1995 through 2014 or 2015) and Medicaid data (1999 through 2009). The final follow-up date ranged from 11 to 21 years after randomization.

Exposures

Receipt of a traditional or low-poverty voucher vs control group.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Rates of hospitalizations and hospital days, and hospital spending.

Results

Among 4602 eligible individuals randomized as adults, 4072 (88.5%) were linked to health data (mean age, 33 years [SD, 9.0 years]; 98% female; median follow-up, 11 years). There were no significant differences in primary outcomes among adults randomized to receive a voucher compared with the control group (unadjusted hospitalization rate, 14.0 vs 14.7 per 100 person-years, adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.95 [95% CI, 0.84-1.08; P = .45]; hospital days, 62.8 vs 67.0 per 100 person-years; IRR, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.77-1.13; P = .46]; yearly spending, $2075 vs $1977; adjusted difference, −$129 [95% CI, −$497 to $239; P = .49]). Among 11 290 eligible individuals randomized as children, 9118 (80.8%) were linked to health data (mean age, 8 years [SD, 4.6 years]; 49% female; median follow-up, 11 years). Receipt of a housing voucher during childhood was significantly associated with lower hospitalization rates (6.3 vs 7.3 per 100 person-years; IRR, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.73-0.99; P = .03]) and yearly inpatient spending ($633 vs $785; adjusted difference, −$143 [95% CI, −$256 to −$31; P = .01]) and no significant difference in hospital days (25.7 vs 28.8 per 100 person-years; IRR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77-1.11; P = .41]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this exploratory analysis of a randomized housing voucher intervention, adults who received a housing voucher did not experience significant differences in hospital use or spending. Receipt of a voucher during childhood was significantly associated with lower rates of hospitalization and less inpatient spending during long-term follow-up.

This exploratory analysis of data from the Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program, a HUD-sponsored social experiment that randomized public housing families to receive a restricted (low-poverty) vs unrestricted (Section 8) relocation voucher, compares the effects of the program on hospitalization rates and days and hospital spending.

Introduction

High-poverty neighborhoods have been linked to higher use of health care services and increased morbidity and mortality.1,2 These neighborhoods are postulated to harm health through a range of mechanisms,3 including limited access to health-promoting resources4,5 and increased exposure to crime,6 low-quality housing,7 and environmental toxins.8 Prior studies, however, have largely been observational and thereby limited by the nonrandom decisions families make about where to live and other unobservable differences that may affect outcomes.

The Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program (MTO) provided a window into examining the association of neighborhood poverty with long-term health care utilization. In 5 states, 4604 families with children living in selected public housing developments in high-poverty neighborhoods were randomized to receive different types of housing vouchers, thereby providing differential access to low-poverty neighborhoods.9 Prior research comparing these voucher groups with a control group observed some positive health outcomes among adults10,11 and children12,13 and improvements in earnings and educational attainment among children who were randomized at a young age.14 However, differences in self-reported measures of access to health care, including having a usual source of care and use of the emergency department, were not observed,9 although self-reported measures may differ substantially from administrative records, which may cover longer periods of time and have less misclassification.15

This study was designed to evaluate the association of receipt of housing vouchers with subsequent hospital utilization and spending among adults and children by linking study participants to state all-payer hospital discharge and Medicaid administrative data.

Methods

MTO Data

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) social experiment was designed to assess the effect of residential location on economic, educational, and other outcomes.9 This intervention was approved by the Office of Management and Budget, HUD, and appropriate institutional review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from adults and written adult/parent consent and adolescent assent was obtained for children and adolescents. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the current analyses. From 1994 to 1998, residents of public housing developments in 5 cities (Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Los Angeles, California; and New York, New York) who lived in selected public housing developments located in high-poverty neighborhoods (at least 40% poverty based on the 1990 US Census) were invited to participate. Participants were randomized using a computerized random-number generator to (1) receive an experimental voucher to move to a low-poverty neighborhood; (2) receive a traditional, unrestricted Section 8 voucher; or (3) a control group that did not receive a voucher. The low-poverty voucher group received short-term moving counseling and a voucher that could only be used to rent a home in a low-poverty neighborhood, defined as a census tract with less than 10% poverty. After 1 year, families with a low-poverty voucher could relocate without restrictions on neighborhood poverty. The traditional voucher group neither received mobility counseling nor had restrictions on where they could rent based on neighborhood poverty. Across the 3 groups, housing assistance limited household contributions to rent and housing to a maximum of 30% of income.

Study Sample

Data on the primary adult respondents and children were provided by HUD. The study excluded participants without known Social Security numbers and those who died before the years of available administrative data. Participants were divided into 2 groups, adults and children (younger than 18 years) at the time of randomization, and based on prior findings in the literature,12,13,14 2 subcohorts of children were also examined: (1) children younger than 13 years vs adolescents (aged 13-17 years) at randomization and (2) boys vs girls.

Administrative Health Data

State all-payer data, which include hospitalizations across all payers, was obtained from 1995 to 2015 for California and New York and from 2004 to 2014 for Massachusetts (eAppendix A in the Supplement). The New York and California data start the first full calendar year after randomization and, depending on which year a participant was randomized, continue through years 17 to 21 after randomization. The Massachusetts data start 7 to 10 years after randomization and continue through 17 to 20 years following randomization.

Medicaid claims data covering 1999 to 2009 for California, Illinois, Maryland, and New York were requested from the Research Data Assistance Center. These data correspond to years 1-5 through years 11-15 following randomization. Because the state all-payer data for California and New York cover more years of utilization and include all participants, Medicaid data for California and New York from 1999 to 2009 were used only in sensitivity analyses.

All records were linked to study participants based on Social Security number, date of birth, and sex. To both have the analyses represent as many participants as possible across all 5 study sites and increase the sample size, the primary analyses pooled the all-payer hospital discharge data from California, Massachusetts, and New York and Medicaid data from Illinois and Maryland.

Dependent Variables

Three primary dependent variables were constructed: the number of hospitalizations per year, the number of inpatient hospital days per year, and total annual hospital spending (eAppendix B in the Supplement). Each was top-coded at the 99th percentile of nonzero values within each state’s subsamples of adults and children to reduce the potential influence of outliers. The primary analyses examined all types of hospitalizations. The secondary analyses distinguished between hospitalizations initiated from the emergency department vs hospitalizations not initiated from the emergency department and between pregnancy-related vs non–pregnancy-related hospitalizations.

State all-payer discharge data reported hospital charges. Each claim’s charges were converted to costs using cost-to-charge ratio data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS) for 1995 to 2015.16,17 HCRIS cost-to-charge data were merged to each hospital by year for Massachusetts and New York, and zip code–level annual mean cost-to-charge ratios were computed for California. Total payments are reported in the Medicaid data for all fee-for-service hospitalizations but are missing from managed care organization admissions. Managed care payments were imputed based on mean payments per day from the fee-for-service admissions. Hospital costs and payments were inflated to 2015 dollars using the Personal Health Care Expenditure inflator ratios from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.18

Main Independent Variables

The primary independent variable was being randomized to receive a housing voucher vs the control condition. Consistent with several prior studies,19,20,21 the analysis combined the 2 voucher groups when analyzing their association with outcomes. Combining the voucher groups increased statistical power and facilitated interpretation of the results. In sensitivity analyses, the voucher groups were analyzed separately (eAppendix F in the Supplement).

Covariates

Covariates derived from the baseline survey included age, sex, race/ethnicity, head-of-household educational status, and whether the head of household was currently working, had ever been married, or was younger than 18 years at the birth of their first child. Study site, year of randomization, calendar year (corresponding to the annual utilization/spending measure), and indicators for any Medicaid managed care during the year and partial-year Medicaid enrollment were also included as covariates (eAppendix C in the Supplement). Self-reported race/ethnicity based on fixed categories was included given its known association with neighborhood characteristics.22

Statistical Analyses

The analyses used longitudinal models with person-year as the unit of observation (eAppendix D in the Supplement). Adults and those who were children at the time of randomization were examined separately; younger (<13 years old) vs older children and boys vs girls were also examined separately. Negative binomial regression models were used to estimate incidence rate ratios for annual hospitalizations and inpatient days. Standard 2-part models, in which the first part is a logistic regression for any spending and the second part is a generalized linear model with a log link and gamma distribution for nonzero spending, were used to estimate differences in annual hospital spending.23 An offset term indicating the total months of available data for a participant in a given year was included in all models. The key independent variable was an indicator for being randomized to either voucher group, and the models adjusted for the covariates described above. Cluster-robust standard errors were estimated using generalized estimating equations to account for both the correlation between repeated, annual observations from the same individual and clustering of children within families. Observations were weighted by the National Bureau of Economic Research survey sample weights to control for possible confounding induced by the varying randomization probabilities over the study’s accrual period.9 The consistency of the association of the housing voucher intervention on the primary outcomes (1) over time and (2) between subgroups of children (younger vs older; girls vs boys) was assessed through models that included the intervention, the subgroup, and their interaction. Missing data on baseline characteristics (<5% of participants) were imputed by site, study group, age, and sex.9 For all analyses, P values are 2-sided and P < .05 indicates statistical significance. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings of the analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Sensitivity and Additional Analyses

In sensitivity analyses, models were estimated with separate indicators for the low-poverty voucher and Section 8 study groups and, due to the heterogeneity of the data across states, years, and sources, using several different combinations of data (eAppendix F in the Supplement). Alternative specifications of the outcome measures used different top-coding approaches and used imputed payments for both Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care. Additional analyses excluded person-year observations for participants known to live out of state in 2009.

Two additional sets of analyses were conducted to assist with the interpretation of the magnitude of the findings. The first set of analyses presents the magnitude of the difference in hospital use for a 10-percentage-point decrease in neighborhood poverty; however, these analyses should not be interpreted as isolating neighborhood poverty from other neighborhood attributes associated with poverty. Consistent with the approach of prior analyses,10,24 a 2-stage model was estimated in which the first-stage model examined average census tract poverty during the first 3 years after randomization as a function of the study groups, the sites, and their interactions, and the second-stage model examined utilization/spending for year 4 onward as a function of the first stage’s predicted neighborhood poverty. A second set of analyses accounts for the fact that not all participants who received a voucher moved; also consistent with the approach of prior analyses,24 treatment-on-treated models were estimated to produce an unbiased estimate of the magnitude for those who actually used their voucher to move.

Results

Of the 4602 primary adult respondents, 4072 (88.5%) were included in this study, contributing 54 569 total person-years of data, with a median of 11 years of follow-up per person (Table 1). Across study groups, the median adult age at randomization was 32 years; 64% were black, 32% were Hispanic, and nearly all (98%) were female. A quarter of the adults were employed and more than a third (37%) received a high school diploma. Among the 11 290 participants who were randomized as children, 9118 (80.8%) were included, contributing 122 128 person-years of data, with a median of 11 years of follow-up per person. Their median age was 8 years at randomization and 49% were female. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between study groups in the adult and child samples.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Matched MTO Study Populationa.

| Characteristics | Adult Sample (Aged ≥18 y at Randomization) | Child Sample (Aged <18 y at Randomization) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voucher Groups (n = 2806) | Control Group (n = 1266) | Voucher Groups (n = 6247) | Control Group (n = 2871) | |

| Age, median (IQR)b | 32 (27-38) | 33 (26-38) | 8 (4-12) | 7 (4-11) |

| Race, No./total (%)c | ||||

| Black | 1746/2757 (63) | 794/1239 (64) | 4027/6108 (66) | 1788/2785 (64) |

| White | 208/2757 (8) | 103/1239 (8) | 391/6108 (6) | 207/2785 (7) |

| Other | 803/2757 (29) | 342/1239 (28) | 1690/6108 (28) | 790/2785 (28) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No. (%)c | 888 (32) | 397 (32) | 1874 (30) | 935 (33) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Femaled | 2751 (98) | 1228 (97) | 3133 (50) | 1459 (51) |

| Male | 55 (2) | 38 (3) | 3114 (50) | 1412 (49) |

| Study site, No. (%) | ||||

| Baltimore, Maryland | 335 (12) | 141 (11) | 877 (14) | 389 (14) |

| Boston, Massachusetts | 607 (22) | 309 (24) | 1197 (19) | 661 (23) |

| Chicago, Illinois | 520 (19) | 180 (14) | 1418 (23) | 456 (16) |

| Los Angeles, California | 571 (20) | 345 (27) | 1325 (21) | 775 (27) |

| New York, New York | 773 (28) | 291 (23) | 1430 (23) | 590 (21) |

| Never married, No. (%) | 1699 (62) | 780 (63) | ||

| Aged <18 y at first childbirth, No. (%) | 687 (26) | 296 (25) | ||

| Employed, No. (%)e | 696 (26) | 303 (25) | ||

| Enrolled in school, No. (%)e | 456 (17) | 197 (16) | ||

| High school diploma, No. (%)e | 1046 (37) | 458 (36) | ||

| GED certificate, No. (%)e | 502 (18) | 234 (18) | ||

| Neighborhood poverty rate in years 1-3 after randomization, mean (SD)f | 37 (15) | 47 (14) | 38 (16) | 47 (14) |

| Years of data, median (IQR)g | 11 (10-18) | 11 (11-18) | 11 (10-18) | 11 (11-18) |

| Years of Medicaid data, median (IQR)g | 6 (3-9) | 6 (3-10) | 8 (5-11) | 8 (5-10) |

| Years of all-payer data, median (IQR)g | 18 (11-19) | 18 (11-19) | 18 (11-19) | 18 (11-19) |

Abbreviations: GED, General Education Development; IQR, interquartile range; MTO, Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program.

Numbers are unweighted data. Percentages were calculated with sample weights accounting for changes in random-assignment ratios across randomized study groups and for subsample interviews. Percentages include imputed values. Omnibus χ2 tests failed to reject the null hypothesis that baseline characteristics are the same between study groups (P = .72 for adults; P = .98 for children).

Imputed age at randomization in whole years.

Race categories do not sum to total numbers because of missing data. The “other” race category includes American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other races. A Hispanic person could be a member of any race.

Adult participants are mostly female because of the high proportion of female-headed households and preferential selection of female respondents in other households.

Employment and current education status at baseline were self-reported by each adult head of household in the year of randomization. Being employed was defined as working either full time or part time for pay.

Based on the proportion of households in a census tract with total family income below the federal poverty line, weighted by the amount of time a participant lived in each census tract.

For the all-payer samples from California, New York, and Massachusetts, this is the number of years potentially in the data, incorporating deaths. For the Medicaid samples from Illinois and Maryland, this is the number of years actually enrolled in Medicaid. Of the 54 569 person-years for adults in the analyses, 46 159 (85%) were from all-payer data and 8410 (15%) were from Medicaid data. Of the person-years of adult Medicaid data, 5911 (70%) were full-year enrollment and 4210 (50%) were managed care. Of the 122 128 person-years for children at the time of randomization, 96 510 (79%) were from all-payer data and 25 618 (21%) were from Medicaid data. Of the person-years for children’s Medicaid data in the analysis, 20 099 (78%) were full-year enrollment and 14 994 (59%) were managed care.

The mean neighborhood poverty rate during the first 3 years after randomization was 37% for the voucher groups compared with 47% for the control group. Among households in the low-poverty voucher group, 47% used their voucher, and the mean neighborhood poverty rate was 37%. Among households in the traditional voucher group, 62% used their voucher, and the mean neighborhood poverty rate was 38% (eAppendix A in the Supplement).

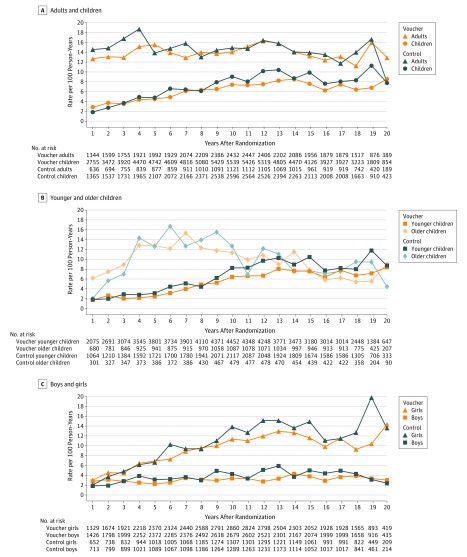

Among participants who were adults at the time of randomization, the subsequent unadjusted rate of hospitalizations during the entire follow-up period was 14.0 per 100 person-years in the voucher groups vs 14.7 per 100 person-years in the control group (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of hospitalizations (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84-1.08; P = .45), hospital days (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.77-1.13; P = .46), or annual spending (difference, −$129; 95% CI, −$497 to $239; P = .49) between the voucher groups and the control group. Differences in the housing voucher intervention’s associations over time for adults were not observed for any of the primary outcomes (Figure 1 and eAppendix E in the Supplement).

Table 2. Inpatient Hospitalizations, Inpatient Days, and Annual Spending Among Voucher Groups vs Control Groupa.

| Voucher Groups, Meanb | Control Group, Meanb | Incidence Rate Ratio or Adjusted Difference (95% CI)c | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (n = 4072; 54 569 person-years) | ||||

| Hospitalizations, No. per 100 person-years | 14.0 | 14.7 | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.08) | .45 |

| Inpatient days, No. per 100 person-years | 62.8 | 67.0 | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.13) | .46 |

| Hospital spending, $ | 2075 | 1977 | –129 (–497 to 239) | .49 |

| Children (n = 9118; 122 128 person-years) | ||||

| Hospitalizations, No. per 100 person-years | 6.3 | 7.3 | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.99) | .03 |

| Inpatient days, No. per 100 person-years | 25.7 | 28.8 | 0.92 (0.77 to 1.11) | .41 |

| Hospital spending, $ | 633 | 785 | –143 (–256 to –31) | .01 |

| Younger children (n = 7244; 96 983 person-years) | ||||

| Hospitalizations, No. per 100 person-years | 5.3 | 6.6 | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.98) | .02 |

| Inpatient days, No. per 100 person-years | 26.1 | 25.7 | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.07) | .18 |

| Hospital spending, $ | 500 | 713 | –196 (–307 to –84) | <.001 |

| Older children (n = 1874; 25 145 person-years) | ||||

| Hospitalizations, No. per 100 person-years | 9.9 | 10.2 | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.18) | .75 |

| Inpatient days, No. per 100 person-years | 43.2 | 40.0 | 1.11 (0.77 to 1.61) | .58 |

| Hospital spending, $ | 1133 | 1088 | 121 (–160 to 401) | .40 |

| Girls (n = 4526; 61 287 person-years) | ||||

| Hospitalizations, No. per 100 person-years | 9.4 | 10.9 | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98) | .03 |

| Inpatient days, No. per 100 person-years | 30.1 | 36.8 | 0.84 (0.70 to 1.01) | .07 |

| Hospital spending, $ | 761 | 1039 | –213 (–370 to –56) | .01 |

| Boys (n = 4592; 60 841 person-years) | ||||

| Hospitalizations, No. per 100 person-years | 3.1 | 3.8 | 0.86 (0.67 to 1.11) | .24 |

| Inpatient days, No. per 100 person-years | 21.1 | 20.8 | 1.02 (0.75 to 1.38) | .92 |

| Hospital spending, $ | 503 | 532 | –20 (–159 to 118) | .77 |

Adults were aged ≥18 years at randomization; children were aged <18 years at randomization; younger children were aged <13 years at randomization; older children were aged 13 to 17 years at randomization; girls and boys were aged <18 years at randomization.

Hospital spending data are reported in annual dollars inflated to 2015 dollars. For the number of hospitalizations and inpatient days, means were estimated from intercept-only negative binomial regression models with an offset term for the total months of available data for a person-year and survey sample weights to account for varying sample probabilities over the accrual period; for hospital spending, means were weighted average annual spending using the survey sampling weights to account for varying sampling probabilities during accrual.

These estimates compare outcomes for everyone assigned to the voucher groups with outcomes for everyone assigned to the control group, with adjustments made for the set of baseline covariates as described in the text. For the models using utilization count data (ie, the total number of annual hospitalizations and the total number of annual hospital days), incidence rate ratios were estimated from negative binomial models with an offset term indicating the total months of available data for a person. For the models using total annual hospital spending data, a difference in dollars was estimated from 2-part spending models, where the first part is a logistic regression for any spending and the second part is a generalized linear model with a log link and gamma distribution for nonzero spending; the 2-part model’s results are presented as combined average marginal effects. The models included survey sample weights to account for varying sampling probabilities over the accrual period and accounted for the family unit by clustering all standard errors by family.

Figure 1. Annual Rates of Hospitalizations.

Rates are based on intercept-only negative binomial models for each year after randomization with an offset term for the total months of available data for the given year and survey sample weights to account for varying sample probabilities over the accrual period. For the adults and children sample, the available data in year 21 after randomization were limited to 47 and 90 observations, respectively; their corresponding rates are not included in panel A or in the child subgroups in panels B and C. The median years of data are 11 (interquartile range, 10-18) for both adults and children in the voucher groups and 11 (interquartile range, 11-18) for both adults and children in the control group. In adjusted models, the interactions for study group by child age (panel B) and child sex (panel C) were not statistically significant, so no formal statistical testing was performed.

Among participants who were children at the time of randomization, the unadjusted rate of hospitalizations during the follow-up period was 6.3 per 100 person-years in the voucher group vs 7.3 per 100 person-years in the control group (IRR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.99; P = .03) (Table 2). The unadjusted mean yearly hospital spending was $633 in the voucher groups vs $785 in the control group (adjusted difference, −$143; 95% CI, −$256 to −$31; P = .01). There were no statistically significant differences in inpatient days for children (unadjusted rate of 25.7 per 100 person-years in the voucher groups vs 28.8 per 100 person-years in the control group; adjusted IRR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.77-1.11; P = .41). Differences in the housing voucher intervention’s associations over time for children were not observed for any of the primary outcomes (Figure 1 and eAppendix E in the Supplement).

With respect to subgroups, the association between receipt of a housing voucher and hospital spending was significantly different for younger children compared with older children (P = .02 for interaction) (eAppendix E in the Supplement). Significantly lower yearly hospital spending was observed among children whose families received vouchers at a younger age (<13 years old) compared with the control group (adjusted difference, −$196; 95% CI, −$307 to −$84; P < .001). No differences in hospital spending were observed among older children (adjusted difference, $121; 95% CI, −$160 to $401; P = .40).

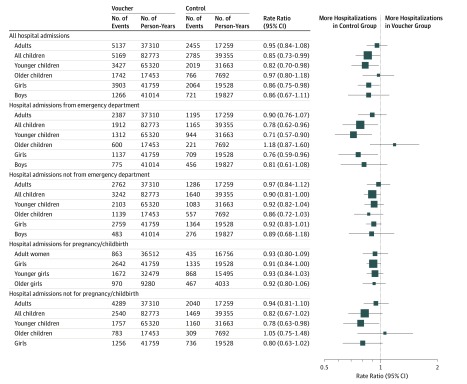

Similar findings were observed for some secondary outcomes (ie, distinguishing between hospitalizations initiated from the emergency department vs those not initiated from the emergency department and between pregnancy-related vs non–pregnancy-related hospitalizations) among children who received a voucher compared with those in the control group but not among adults (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Primary and Secondary Hospitalization Outcomes.

Hospitalizations were categorized according to whether or not they originated in the emergency department or were related to pregnancy/childbirth. Incidence rate ratios are expressed as the voucher groups relative to the control group and were derived from negative binomial regression models for the count of hospitalizations with person-year as the unit of observation and adjustments made for the set of covariates described in the text. The models included survey sample weights to account for varying sampling probabilities over the accrual period and accounted for family unit by clustering all standard errors by family. The size of the data markers is proportional to the number of person-years of data available.

The results were generally robust to the sensitivity analyses (eAppendix F in the Supplement). In particular, results from models that included separate indicator variables for the 2 voucher groups were not significantly different from each other for any outcome, thus supporting the approach of combining the voucher groups in the analyses. Using different combinations of data suggested that including all-payer data (compared with analyzing Medicaid data alone) yielded larger differences in hospital spending between study groups, although with overlapping confidence intervals (eg, the adjusted difference for voucher vs control hospital spending among children was −$21 [95% CI, −$128 to $87] when using the Medicaid data alone and −$142 [95% CI, −$279 to −$5] when analyzing only all-payer data (eTables F3-F7 in eAppendix F in the Supplement).

Additional analyses present the difference in hospital use associated with a 10-percentage-point decrease in neighborhood poverty (Table 3). For children at randomization, a 10-percentage-point decrease in average neighborhood poverty during years 1 through 3 after randomization was significantly associated with a lower admission rate (IRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.80-0.99; P = .03) and $133 less in yearly hospital spending (95% CI, −$237 to −$28; P = .01), but there was no significant difference in hospital days (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.79-1.10; P = .41). Additional treatment-on-treated analyses show the alternative magnitudes of the relationship when accounting for nonuniversal voucher take-up (eAppendix E in the Supplement).

Table 3. Hospital Use Associated With a 10-Percentage-Point Decrease in Predicted Neighborhood Poverty Ratesa.

| Hospitalizations | Inpatient Days | Hospital Spending, $ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value | Absolute Estimate (95% CI)b | P Value | |

| Adults | 0.95 (0.85-1.08) | .45 | 0.94 (0.80-1.11) | .46 | –68 (–424 to 288) | .71 |

| Children | 0.88 (0.80-0.99) | .03 | 0.93 (0.79-1.10) | .41 | –133 (–237 to –28) | .01 |

| Younger children | 0.88 (0.79-1.00) | .05 | 0.93 (0.79-1.11) | .45 | –152 (–256 to –49) | .004 |

| Older children | 0.90 (0.78-1.05) | .20 | 0.83 (0.61-1.15) | .27 | –23 (–287 to 242) | .87 |

| Girls | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) | .02 | 0.88 (0.76-1.01) | .08 | –188 (–335 to –42) | .01 |

| Boys | 0.90 (0.74-1.10) | .30 | 1.00 (0.76-1.30) | .98 | –38 (–170 to 94) | .57 |

Adults were aged ≥18 years at randomization; children were aged <18 years at randomization; younger children were aged <13 years at randomization; older children were aged 13 to 17 years at randomization; girls and boys were aged <18 years at randomization.

These models used predicted reductions in neighborhood poverty as the key explanatory variable for hospital utilization/spending, with these estimates specifically showing the change in outcomes associated with a 10-percentage-point decrease in predicted neighborhood poverty exposure (to be consistent with the housing voucher intervention’s association with reductions in neighborhood poverty compared with the control group). The first-stage regression was an ordinary least-squares model with the mean duration-weighted percentage of households in the census tract with incomes above the poverty line as the dependent variable (so that differences in this first-stage outcome and subsequent predictions can be interpreted as a reduction in poverty), the study group voucher indicators and the site and study group voucher interactions as the main predictors, and the baseline characteristics and sites as controls. For the main analyses, the second-stage regression uses the predicted duration-weighted percentage of families above the poverty line from years 1 through 3 after randomization as the key explanatory variable and hospital utilization/spending from years 4 through 21 after randomization as the dependent variable, adjusting for baseline covariates. For the models using utilization count data (ie, the total number of annual hospitalizations and the total number of annual hospital days), incidence rate ratios were estimated from negative binomial models with an offset term indicating the total months of available data for a person. For the models using total annual hospital spending data, a difference in dollars was estimated from 2-part spending models, in which the first part is a logistic regression for any spending and the second part is a generalized linear model with a log link and gamma distribution for nonzero spending; the 2-part model’s results are presented as combined average marginal effects. The models included survey sample weights to account for varying sampling probabilities over the accrual period and accounted for the family unit by clustering all standard errors by family.

Discussion

In this exploratory analysis, among participants who were randomized as adults there were no significant associations of voucher receipt and neighborhood poverty exposure with hospitalizations, hospital days, or spending. However, among participants who were children at the time of randomization, receipt of a voucher and lower exposure to neighborhood poverty were associated with a significantly lower rate of hospitalizations and less inpatient spending but no significant difference in hospital days compared with children in the control group. These findings are potentially relevant for the approximately 4 million children living in low-income households receiving HUD assistance25; these children live in neighborhoods with a mean neighborhood poverty rate of 27%,26 and policy attention has focused on efforts to reduce neighborhood poverty exposure.27,28

The nonsignificant findings for those who were adults at the time of randomization and the significant findings among those who were children, and especially young children, at the time of randomization are consistent with the economic outcomes examined by Chetty and colleagues,14 who observed a 14% increase in earnings and 16% increase in college attendance among children whose families received a voucher when the children were at a young age. These economic differences are similar to the health care findings observed herein among younger children who received a housing voucher: a lower hospitalization rate and less annual hospital spending. The observed differences in annual inpatient spending were persistent over a long period (up to 21 years in the current study) and would thus be associated with large cumulative differences.

In accordance with a life-course perspective,29 it is possible that neighborhood poverty exposure may be particularly important for subsequent health care use during certain developmental windows. Future analyses could consider whether alternative outcomes other than those examined herein—for example, focusing on outpatient care—may better correlate with the reductions in diabetes and obesity observed in adults in prior analyses.10

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the observed reduction in hospital utilization may have been due to better health, decreased access to care if health remained constant, or some combination of both; health care use is a function of multiple factors, including access, that may have been affected by the study and warrants careful scrutiny. For instance, families who moved to different neighborhoods as a result of the voucher receipt may have experienced health care at hospitals and other facilities that differ in their practice style, billing practices, and other aspects of care, which may affect the findings. Future analyses could link participants to locational data on health care resources to assess potential access to care. Second, the generalizability of the study is limited, as only 23% of eligible families volunteered to participate in the study.9 Moreover, uptake of the vouchers was relatively low, and among those who moved, the duration of time in a low-poverty neighborhood was often short. At the same time, exposure to neighborhood poverty decreased in the control group over time, which, taken together, may attenuate differences between study groups. Third, there were several limitations of the health utilization data. There were nontrivial missing data for the data linkage based on lack of Social Security numbers, and there were also no baseline health data for study participants, although it is unlikely these factors were different across study groups. For the all-payer data, eligible participants who did not link up to any claims were assumed to have no hospital claims during the year; this assumption may be incorrect for participants who moved out of state. Although significant differences in out-of-state residence in 2009 by study group were observed for the adult sample but not for the child sample (eAppendix A in the Supplement), sensitivity analyses were robust to excluding data for these participants (eAppendix F in the Supplement). Analyzing all-payer and Medicaid data together poses challenges related to the differences between them (eg, charges/costs vs payments), which are adjusted for in the models. There are also limitations with the Medicaid data, including the need to impute managed care organization payments30 and potential differences in Medicaid enrollment related to the experiment, even though analyses did not find differential overall or managed care enrollment by study group (eAppendix C in the Supplement).

Conclusions

In this exploratory analysis of a randomized housing voucher intervention, adults who received a housing voucher did not experience significant differences in hospital use or spending. Receipt of a voucher during childhood was significantly associated with lower rates of hospitalization and less inpatient spending during long-term follow-up.

eAppendix A. Overview of Data Sources and Cohort Derivation

eAppendix B. Coding of Outcome Variables

eAppendix C. Coding of Covariates

eAppendix D. Statistical Analyses/Methodology

eAppendix E. Additional Results: Primary/Secondary Analyses

eAppendix F. Results for Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences

References

- 1.Taylor L. Housing and Health: An Overview of the Literature Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180313.396577/full/. Published June 7, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2018.

- 2.Waitzman NJ, Smith KR. Phantom of the area: poverty-area residence and mortality in the United States [published correction appears in Am J Public Health. 1998;88(7):1122]. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):973-976. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.6.973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:125-145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):23-29. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00403-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell JF, Wilson JS, Liu GC. Neighborhood greenness and 2-year changes in body mass index of children and youth. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(6):547-553. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258-276. doi: 10.2307/3090214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson M, Petticrew M, Bambra C, Sowden AJ, Wright KE, Whitehead M. Housing and health inequalities: a synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health Place. 2011;17(1):175-184. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morello-Frosch R, Shenassa ED. The environmental “riskscape” and social inequality: implications for explaining maternal and child health disparities. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(8):1150-1153. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanbonmatsu L, Ludwig J, Katz LF, et al. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program—Final Impacts Evaluation US Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.huduser.gov/publications/pdf/MTOFHD_fullreport_v2.pdf. Published November 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 10.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1509-1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337(6101):1505-1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1224648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Associations of housing mobility interventions for children in high-poverty neighborhoods with subsequent mental disorders during adolescence adolescence [retracted and replaced June 17, 2016]. JAMA. 2014;311(9):937-948. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Clampet-Lundquist S, Kling JR, Edin K, Duncan GJ. Moving teenagers out of high-risk neighborhoods: how girls fare better than boys. AJS. 2011;116(4):1154-1189. doi: 10.1086/657352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF. The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. Am Econ Rev. 2016;106(4):855-902. doi: 10.1257/aer.20150572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, Baicker K, Finkelstein AN. Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon’s Health Insurance Experiment. Science. 2014;343(6168):263-268. doi: 10.1126/science.1246183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healthcare Cost Report Information System. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Cost-Reports/. Published October 26, 2018. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- 17.Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS) data. National Bureau of Economic Research website. https://www.nber.org/data/hcris.html. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- 18.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Using appropriate price indices for analyses of health care expenditures or income across multiple years. https://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml. Published 2016. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 19.Nguyen QC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. The effects of a housing mobility experiment on participants’ residential environments. Hous Policy Debate. 2017;27(3):419-448. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2016.1245210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudolph KE, Sofrygin O, Schmidt NM, et al. Mediation of neighborhood effects on adolescent substance use by the school and peer environments. Epidemiology. 2018;29(4):590-598. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph KE, Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, et al. Composition or context: using transportability to understand drivers of site differences in a large-scale housing experiment. Epidemiology. 2018;29(2):199-206. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University The State of the Nation’s Housing https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2019.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 23.Deb P, Norton E, Manning W. Health Econometrics Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kling J, Liebman J, Katz L. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica. 2007;75(1):83-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0262.2007.00733.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research A Health Picture of HUD-Assisted Children https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-research-041618.html. Published 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 26.US Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research Picture of subsidized households. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/assthsg.html. Published 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 27.Rice D. House bill includes major investments to help families pay rent. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-bill-includes-major-investments-to-help-families-pay-rent. Published May 22, 2019. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 28.HUD Exchange Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH). https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/affh/. Accessed September 11, 2019.

- 29.Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(2):205-219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrd V, Dodd A. Assessing the Usability of Encounter Data for Enrollees in Comprehensive Managed Care Across MAX 2007-2009. Mathematica Policy Research. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/Downloads/MAX_IB_15_AssessingUsability.pdf. Published December 2012. Accessed September 11, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix A. Overview of Data Sources and Cohort Derivation

eAppendix B. Coding of Outcome Variables

eAppendix C. Coding of Covariates

eAppendix D. Statistical Analyses/Methodology

eAppendix E. Additional Results: Primary/Secondary Analyses

eAppendix F. Results for Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences