Key Points

Question

Are maternal eating disorders associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes?

Findings

In this cohort study comprising all singleton births in Sweden between 2003 and 2014, maternal eating disorders were associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as antepartum hemorrhage, and with adverse neonatal outcomes, such as preterm birth, small size for gestational age, and microcephaly. The risk of most of these outcomes was most pronounced in women with an active eating disorder but was also significantly increased in women with a previous eating disorder.

Meaning

Eating disorders appear to be associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes; these results highlight the importance of acknowledging eating disorders among pregnant women and considering the potential association with maternal and neonatal health.

Abstract

Importance

The prevalence of eating disorders is high among women of reproductive age, yet the association of eating disorders with pregnancy complications and neonatal health has not been investigated in detail, to our knowledge.

Objective

To investigate the relative risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes for women with eating disorders.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study included all singleton births included in the Swedish Medical Birth Register from January 1, 2003, to December 31, 2014. A total of 7542 women with eating disorders were compared with 1 225 321 women without eating disorders. Statistical analysis was performed from January 1, 2018, to April 30, 2019. Via linkage with the national patient register, women with eating disorders were identified and compared with women free of any eating disorder. Eating disorders were further stratified into active or previous disease based on last time of diagnosis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (hyperemesis, anemia, preeclampsia, and antepartum hemorrhage), the mode of delivery (cesarean delivery, vaginal delivery, or instrumental vaginal delivery), and the neonatal outcomes (preterm birth, small and large sizes for gestational age, Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes, and microcephaly) were calculated using Poisson regression analysis to estimate risk ratios (RRs). Models were adjusted for age, parity, smoking status, and birth year.

Results

There were 2769 women with anorexia nervosa (mean [SD] age, 29.4 [5.3] years), 1378 women with bulimia nervosa (mean [SD] age, 30.2 [4.9] years), and 3395 women with an eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS; mean [SD] age, 28.9 [5.3] years), and they were analyzed and compared with 1 225 321 women without eating disorders (mean [SD] age, 30.3 [5.2] years). All subtypes of maternal eating disorders were associated with an approximately 2-fold increased risk of hyperemesis during pregnancy (anorexia nervosa: RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.8-2.5]; bulimia nervosa: RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.6-2.7]; EDNOS: RR, 2.6 [95% CI, 2.3-3.0]). The risk of anemia during pregnancy was doubled for women with active anorexia nervosa (RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.3-3.2]) or EDNOS (RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.5-2.8]). Maternal anorexia nervosa was associated with an increased risk of antepartum hemorrhage (RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.2-2.1]), which was more pronounced in active vs previous disease. Women with anorexia nervosa (RR, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.6-0.9]) and women with EDNOS (RR, 0.8 [95% CI, 0.7-1.0]) were at decreased risk of instrumental-assisted vaginal births; otherwise, there were no major differences in mode of delivery. Women with eating disorders, all subtypes, were at increased risk of a preterm birth (anorexia nervosa: RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.4-1.8]; bulimia nervosa: RR, 1.3 [95% CI, 1.0-1.6]; and EDNOS: RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.6]) and of delivering neonates with microcephaly (anorexia nervosa: RR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.5-2.4]; bulimia nervosa: RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.1-2.4]; EDNOS: RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.9]).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that women with active or previous eating disorders, regardless of subtype, are at increased risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes and may need increased surveillance in antenatal and delivery care.

This population-based cohort study investigates the relative risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes among Swedish women with eating disorders.

Introduction

Eating disorders are serious diseases affecting a large number of individuals worldwide regardless of race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.1,2 Eating disorders are associated with significant long-term somatic and psychiatric complications, and for 1 in 10 patients, the disease course is chronic.1

The point prevalence of eating disorders is highest among women prior to or during their reproductive years, which generates questions regarding the association of eating disorders with pregnancy.3 To our knowledge, studies on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes among women with ongoing or previous eating disorders are scarce. Nevertheless, a few studies and case reports have reported an increased risk of adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes4,5,6,7,8,9 for women with eating disorders. More important, the results from these previous studies are partly inconsistent, with variations in reported adverse outcomes.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Furthermore, most of these studies have been based on hospital-recruited cohorts and/or are retrospective and have an often low participation rate, making them prone to include biases. Moreover, most of the studies have focused on anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa, whereas none have addressed eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS; the subtype with the highest reported prevalence), and no study has differentiated between active vs previous disease.

Considering the high prevalence of eating disorders among women of reproductive age and the apparent need to clarify the association between eating disorders and pregnancy outcomes, we set out to determine the association of maternal eating disorders with pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal outcomes.

Methods

Study Design, Study Setting, and Data Sources

This national population-based cohort study used data from several nationwide health and population registers. The unique Swedish personal identification number, assigned at birth or immigration,13 was used to link information from several data sources. Ethical approval was granted from the Ethics Committee of Stockholm. No informed consent was required for these anonymized register data.

The Swedish Medical Birth Register (MBR) includes information on more than 98% of all births in Sweden since 1973.14 Information on demographic data, reproductive history, risk factors, comorbidities, and complications during pregnancy, delivery, and the neonatal period is collected prospectively during pregnancy. The National Patient Register (NPR) contains information on inpatient and outpatient care15 and stores information on main and secondary diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] used between 1987 and 1996 and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] in use since 1997). The Education Register, held by Statistics Sweden, includes information on number of years of schooling (categorized into ≤9, 10-12 and ≥12 years).

Study Population

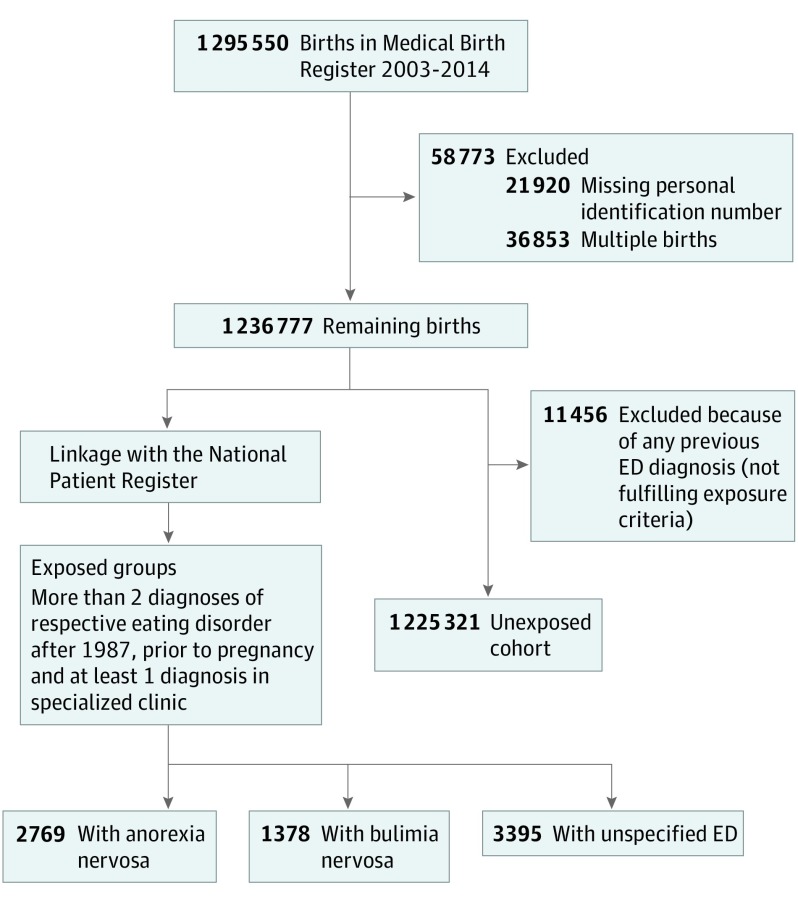

Unexposed and exposed study participants were all identified from the study base consisting of all singleton births included in the MBR between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2014 (see Figure 1 for flowchart of study design).

Figure 1. Flowchart of Study Design and Identification of Exposed and Unexposed Women.

ED indicates eating disorder.

Exposed: Women With Eating Disorders Before Pregnancy

Three separate exposure groups of women with eating disorders before pregnancy were identified using the NPR. Each subtype of eating disorder was defined as at least 2 visits at inpatient or outpatient clinics listing the specific diagnosis (anorexia nervosa: ICD-9 code 307B and ICD-10 codes F50.0 and F50.1; bulimia nervosa: ICD-10 codes F50.2 and F50.3; EDNOS: ICD-9 code 307 and ICD-10 code F50.9) after 1987. Furthermore, at least 1 of the visits had to be at a specialized clinic (psychiatry [child and adolescent or adult], internal medicine, gastroenterology, endocrinology, gynecology, or pediatric). Active eating disorders were defined as a listing within 1 year prior to conception or during the pregnancy period. Previous eating disorders were defined as the last time of diagnosis occurring more than 1 year prior to conception.

Unexposed: Women Without Eating Disorders Before Pregnancy

All women free of any eating disorder diagnosis (main or secondary diagnoses) before the time of conception comprised the unexposed cohort.

Outcomes

Pregnancy outcomes were collected from the MBR and/or the NPR. Hyperemesis (ICD-10 code O21) and anemia (ICD-10 codes O990, D649, D509, D519, D529, and D539) were defined as registered diagnoses in the NPR during pregnancy, and preeclampsia (ICD-10 codes O14 and O15) was defined as a registered diagnosis in the MBR. Antepartum hemorrhage included placenta previa with bleeding (ICD-10 code O44.1), abruptio placentae (ICD-10 code O45), and unspecified antepartum hemorrhage (ICD-10 code O46). Mode of delivery was categorized into vaginal birth, instrumental-assisted vaginal birth, or cesarean delivery (planned or emergency). Postpartum hemorrhage, defined as bleeding more than 1000 mL in relation to delivery, was based on registration in the MBR (ICD-10 codes O67.0, O67.8, and O72). For neonatal outcomes, we assessed preterm birth (<37 gestational weeks, spontaneous and medically indicated), moderate preterm birth (32-36 gestational weeks), very preterm birth (<32 gestational weeks), small for gestational age (SGA), large for gestational age, Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes,16 and microcephaly. Large for gestational age was defined as a birth weight of more than 2 SD above the sex-specific mean for gestational age; likewise, SGA was defined as a birth weight of more than 2 SD below the sex-specific mean for gestational age. Similarly, microcephaly was defined as a head circumference of more than 2 SD below the sex-specific mean for gestational age.17

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed from January 1, 2018, to April 30, 2019. Descriptive baseline variables were tabulated and presented as frequencies, means, or medians, as appropriate. Differences between the exposed groups and nonexposed groups were tested using the χ2 test for dichotomous variables, the t test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney test for ordinal and nonnormally distributed continuous variables. Poisson regression analyses were used to estimate risk ratios (RRs) as a measurement of the relative risk of outcome variables among the exposed groups compared with the unexposed group. Separate models for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and EDNOS and each outcome were used. To account for the occurrence of multiple births from the same mother, the generalized estimation equation method was used. The regression analyses were adjusted for age, parity, smoking, and birth year. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: (1) the exposure definition was changed to 1 or more registered eating disorder diagnoses, (2) main analyses were repeated for study participants with a normal body mass index (BMI), and (3) models with significantly increased RRs were adjusted for psychiatric comorbidities (in addition to age, parity, smoking, and birth year). All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS institute Inc). All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

In 0.1% (1378) of the 1 236 777 births between 2003 and 2014, the women fulfilled the criteria for bulimia nervosa, in 0.2% (2769) of births, the women fulfilled the criteria for anorexia nervosa, and in 0.3% (3395) of births, the women fulfilled the criteria for EDNOS (Figure 1). Demographic data, preexisting comorbidities, smoking, and early pregnancy BMI for all study participants are presented in Table 1. A total of 279 women with anorexia nervosa (10.1%), 239 women with bulimia nervosa (17.3%), and 618 women with EDNOS (18.2%) had active disease. Women with anorexia nervosa or EDNOS were significantly younger than unexposed women (mean [SD] age, 29.4 [5.3] years vs 28.9 [5.3] years vs 30.3 [5.2] years). Among all eating disorder groups, there was a higher proportion of nulliparous women compared with unexposed women. A significantly higher proportion of women with anorexia nervosa (265 [9.6%]) and EDNOS (192 [5.7%]) were underweight compared with unexposed women (26 062 [2.1%]). Smoking was more common among women with any eating disorder compared with unexposed women. The prevalence of all preexisting comorbidities (substance abuse, anxiety disorder, affective disorder, and type 1 and type 2 diabetes) was significantly higher among women with eating disorders regardless of subtype.

Table 1. Maternal Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Women, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Eating Disorder (n = 1 225 321) | Anorexia Nervosa (n = 2769) | Bulimia Nervosa (n = 1378) | Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (n = 3395) | |

| Active or recent EDa | NA | 279 (10.1) | 239 (17.3) | 618 (18.2) |

| Last ED visit, y | ||||

| 2-5 | NA | 790 (28.5) | 611 (44.3) | 1383 (40.7) |

| 6-10 | NA | 885 (32.0) | 451 (32.7) | 1004 (29.6) |

| >10 | NA | 815 (29.4) | 77 (5.6) | 390 (11.5) |

| Maternal age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 30.3 (5.2) | 29.4 (5.3) | 30.2 (4.9) | 28.9 (5.3) |

| <20 | 18 734 (1.5) | 53 (1.9)b | 10 (0.7) | 80 (2.4)b |

| 20-25 | 210 912 (17.2) | 664 (24.0) | 226 (16.4) | 895 (26.4) |

| 26-30 | 397 230 (32.4) | 899 (32.5) | 500 (36.3) | 1151 (33.9) |

| 31-35 | 398 696 (32.5) | 779 (28.1) | 446 (32.4) | 885 (26.1) |

| >35 | 199 741 (16.3) | 374 (13.5) | 196 (14.2) | 384 (11.3) |

| Parity, No. | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.9) |

| 1 | 543 502 (44.4) | 1435 (51.8)b | 713 (51.7)b | 1827 (53.8)b |

| 2 | 450 420 (36.8) | 905 (32.7) | 443 (32.2) | 1073 (31.6) |

| 3 | 162 128 (13.2) | 312 (11.3) | 154 (11.2) | 366 (10.8) |

| >3 | 69 271 (5.7) | 117 (4.2) | 68 (4.9) | 129 (3.8) |

| BMI in early pregnancyc | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.7 (4.6) | 21.5 (3.0)b | 24.3 (4.8) | 23.4 (4.7) |

| <18.5 | 26 062 (2.1) | 265 (9.6)b | 30 (2.2) | 192 (5.7)b |

| 18.5-24.9 | 673 104 (54.9) | 1939 (70.0) | 787 (57.1) | 2073 (61.1) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 284 805 (23.2) | 212 (7.6) | 269 (19.5) | 527 (15.5) |

| ≥30.0 | 136 016 (11.1) | 29 (1.0) | 145 (10.5) | 256 (7.5) |

| Missing | 105 335 (8.6) | 324 (11.7) | 147 (10.7) | 347 (10.2) |

| Smoking, No./total No. (%)d | ||||

| Before pregnancy | 19 503/1 168 435 (16.4) | 510/2667 (19.1)e | 291/1326 (21.9)b | 768/3272 (23.5)b |

| First visit | 81 318/1 167 582 (7.0) | 212/2668 (7.9)e | 118/1329 (8.9)e | 325/3271 (9.9)b |

| Educational level, y | ||||

| ≤9 | 107 459 (8.8) | 242 (8.7) | 112 (8.1) | 373 (11.0) |

| 10-12 | 456 248 (37.2) | 1002 (36.2) | 517 (37.5) | 1398 (41.2) |

| >12 | 652 018 (53.2) | 1523 (55.0) | 747 (54.2) | 1619 (47.7) |

| Missing | 9596 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) |

| Preexisting comorbiditiesf | ||||

| Substance abuse | 24 074 (2.0) | 378 (13.7)b | 263 (19.1)b | 653 (19.2)b |

| Anxiety disorders | 35 118 (2.9) | 721 (26.0)b | 512 (37.2)b | 1358 (40.0)b |

| Depression | 37 819 (3.1) | 953 (34.4)b | 710 (51.5)b | 1760 (51.8)b |

| Type 1 diabetes | 6144 (0.5) | 38 (1.4)b | 32 (2.3)b | 63 (1.9)b |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); ED, eating disorder; NA, not applicable.

Active or recent disease was defined as a registered diagnosis within 1 year prior to start of pregnancy or during the pregnancy period.

P < .001 based on χ2 test for dichotomous variables, t test for normally distributed variables, and Mann-Whitney test for ordinal or nonnormally distributed continuous variables.

Categorized into underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obesity (≥30.0).

Reported in Medical Birth Register.

P < .05 based on χ2 test for dichotomous variables, t test for normally distributed variables, and Mann-Whitney test for ordinal or nonnormally distributed continuous variables.

Based on registered diagnoses in the patient register prior to pregnancy.

Pregnancy Complications and Mode of Delivery

Table 2 displays the association between all eating disorder subtypes and selected pregnancy complications and modes of delivery. The risk of hyperemesis was approximately doubled for women with eating disorders (anorexia nervosa: RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.8-2.5]; bulimia nervosa: RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.6-2.7]; EDNOS: RR, 2.6 [95% CI, 2.3-3.0]). Maternal anorexia nervosa was associated with a 60% increased risk of antepartum hemorrhage (RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.2-2.1]). Women with bulimia nervosa or EDNOS received a diagnosis of anemia more frequently compared with unexposed women (bulimia nervosa: RR, 1.3 [95% CI, 1.1-1.6]; EDNOS: RR, 1.1 [95% CI, 1.0-1.3]). Preeclampsia did not differ between exposed women with any of the eating disorder subtypes and unexposed women. All significant RRs remained similar after adjusting for age, parity, smoking status, and birth year. There was a slightly decreased risk of instrumental-assisted vaginal birth for women with anorexia nervosa (RR, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.6-0.9]) or EDNOS (RR, 0.8 [95% CI, 0.7-1.0]). Cesarean delivery was slightly more common for women with EDNOS than for unexposed women (RR, 1.1 [95% CI, 1.0-1.2]). There were no significant differences in postpartum hemorrhage between exposed and unexposed groups.

Table 2. Pregnancy Complications, Mode of Delivery, and Postpartum Hemorrhage Among Women With Eating Disorders vs Women Without Eating Disorders.

| Characteristic | Unexposed, No. (%) (n = 1 225 321) | Anorexia Nervosa (n = 2769) | Bulimia Nervosa (n = 1378) | EDNOS (n = 3395) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | |||||

| Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | |||||

| Hyperemesis | 27 377 (2.2) | 130 (4.7) | 2.1 (1.8-2.5) | 2.0 (1.7-2.4) | 63 (4.6) | 2.1 (1.6-2.7) | 2.0 (1.5-2.5) | 194 (5.7) | 2.6 (2.3-3.0) | 2.3 (2.0-2.7) |

| Anemia | 120 249 (9.8) | 279 (10.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.9 (0.9-1.1) | 161 (11.7) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.3 (1.0-1.5) | 383 (11.3) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) |

| Preeclampsia | 33 303 (2.7) | 61 (2.2) | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 33 (2.4) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 90 (2.7) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 13 375 (1.1) | 47 (1.7) | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 1.6 (1.2-2.2) | 16 (1.2) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 46 (1.4) | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||||||

| Cesarean | 204 394 (16.7) | 442 (16.0) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 223 (16.2) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.0 (0.8-1.1) | 623 (18.4) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.2 (1.1-1.2) |

| Vaginal | 928 995 (75.8) | 2176 (78.6) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 1058 (76.8) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 2558 (75.4) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) |

| Instrumental assisted | 91 932 (7.5) | 151 (5.5) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 97 (7.0) | 1.0 (0.8-1.1) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 214 (6.3) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 82 479 (6.7) | 151 (5.5) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 101 (7.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 217 (6.4) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

Abbreviations: EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; RR, risk ratio.

Adjusted for smoking status, parity, age, and year of birth.

Neonatal Complications

Frequencies and RRs for neonatal outcomes in women with eating disorders compared with unexposed women are presented in Table 3. There was a 60% increased risk of preterm birth for women with anorexia nervosa (RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.4-1.8]) compared with unexposed women. For women with bulimia nervosa and women with EDNOS, the risk was smaller, but still significantly increased (bulimia nervosa: RR, 1.3 [95% CI, 1.0-1.6]; EDNOS: RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.6]). Risk ratios were similar for moderate and very preterm birth among women with anorexia nervosa and women with bulimia nervosa. Women with EDNOS had a 70% increased risk of very preterm birth (RR, 1.7 [95% CI, 1.3-2.4]) vs a 40% increased risk of moderate preterm birth (RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.6]). The risk was higher for medically induced preterm birth (anorexia nervosa: RR, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.4-2.3]; bulimia nervosa: RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.1-2.3]; EDNOS: RR, 1.7 [95% CI, 1.4-2.3]) than for spontaneous preterm birth. The risk of having an SGA neonate was increased among women with anorexia nervosa (RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.1-1.7]) and women with EDNOS (RR, 1.2 [95% CI, 1.0-1.5]) compared with unexposed women. Maternal anorexia nervosa was associated with an almost 2-fold risk of having a neonate with microcephaly (RR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.5-2.4]). The risk of having a neonate with microcephaly was increased 60% for women with bulimia nervosa (RR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.1-2.4]) and increased 40% for women with EDNOS (RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.9]). A higher proportion of neonates of women with EDNOS compared with neonates of unexposed women presented with an Apgar score below 7 at 5 minutes (RR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.1-1.9]). All significantly increased RRs remained after adjusting for age, parity, smoking status, and birth year.

Table 3. Neonatal Outomes Among Women With Eating Disorders vs Women Without Eating Disorders.

| Outcome | Unexposed, No. (%) (n = 1 225 321) | Anorexia Nervosa (n = 2769) | Bulimia Nervosa (n = 1378) | EDNOS (n = 3395) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | No. (%) | RR (95% CI) | |||||

| Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | |||||

| Preterm birth | 58 822 (4.8) | 210 (7.6) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | 83 (6.0) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 228 (6.7) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

| Spontaneous deliveryb | 40 812 (3.3) | 137 (4.9) | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 51 (3.7) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 142 (4.2) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) |

| Medically induced deliveryb | 18 010 (1.5) | 73 (2.6) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | 32 (2.3) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 86 (2.5) | 1.7 (1.4-2.2) | 1.7 (1.4-2.3) |

| Moderate preterm birthc | 50 661 (4.1) | 182 (6.6) | 1.6 (1.3-1.8) | 1.6 (1.3-1.8) | 72 (5.2) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) | 189 (5.6) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 1.4(1.2-1.6) |

| Very preterm birthd | 8161 (0.7) | 28 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | 1.5 (1.0-2.3) | 11 (0.8) | 1.2 (0.6-2.2) | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 39 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.3-2.4) | 1.8 (1.4-2.6) |

| SGA | 27 081 (2.2) | 85 (3.1) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | 29 (2.1) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 90 (2.7) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

| LGA | 43 302 (3.5) | 56 (2.0) | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 46 (3.3) | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 108 (3.2) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

| Microcephaly | 15 960 (1.3) | 67 (2.4) | 1.9 (1.5-2.4) | 1.7 (1.3-2.1) | 29 (2.1) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) | 64 (1.9) | 1.4 (1.2-1.9) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) |

| Apgar score, <7 in 5 min | 13 760 (1.1) | 34 (1.2) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 1.0 (0.7-1.5) | 19 (1.4) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 1.1 (0.6-1.7) | 54 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) |

Abbreviations: EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; LGA, large for gestational age; RR, risk ratio; SGA, small for gestational age.

Adjusted for smoking status, parity, and age.

Spontaneous or medically induced (planned cesarean or medical induction) delivery onset.

Defined as birth between 32 and 36 gestational weeks.

Defined as birth before 32 gestational weeks.

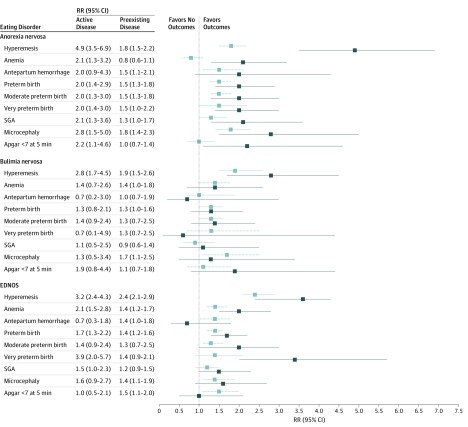

Active vs Preexisting Disease

The results on pregnancy and neonatal complications were stratified into active and preexisting eating disorders and are presented in Figure 2. In general, the RRs for most outcomes were more pronounced for women with active disease vs those with preexisting disease. For instance, the risk of bleeding complications during pregnancy appeared more pronounced for women with active anorexia nervosa (doubled) compared with those with previous anorexia nervosa (1.5-fold). The risk of anemia was doubled for women with active anorexia nervosa (RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.3-3.2]) and for women with EDNOS (RR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.5-2.8]), but the risk was not present for those with previous disease.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of the Risk of Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes in Women With Eating Disorders vs Women Without Eating Disorders.

Solid lines indicate active disease. Dotted light lines indicate preexisting disease. EDNOS indicates eating disorder not otherwise specified; RR, risk ratio; and SGA, small for gestational age.

Similarly, RRs for neonatal outcomes were consequently more pronounced for women with active disease (especially anorexia nervosa), but most RRs for neonatal outcomes also remained significantly increased in women with previous disease. Among women with active EDNOS, there was a 4-fold increased risk of very preterm birth (Figure 2). There was a 2-fold increased risk of having a neonate presenting with an Apgar score below 7 at 5 minutes among women with active anorexia nervosa (RR, 2.2 [95% CI, 1.1-4.6]) compared with unexposed women.

Sensitivity Analyses

Changing the exposure definition to 1 or more registered eating disorder diagnoses did not alter our results (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement). Likewise, RRs among study participants with an early-pregnancy normal BMI remained similar to the RRs of the original analysis (eTables 3-5 in the Supplement). Adjusting models for a history of anxiety or depressive disorder was associated with decreased RRs of hyperemesis across all eating disorder subtypes, whereas RRs for other outcomes remained similar to our main analyses (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This nationwide and population-based study of women with eating disorders and a comparison cohort of women without eating disorders comprises virtually all singleton births in Sweden from 2003 to 2014 and is, to our knowledge, the largest assessment to date of pregnancy and neonatal outcomes among women with eating disorders. Furthermore, to our knowledge, it is the only contemporary study based on an unselected study population including 3 separate eating disorder subtypes attempting to differentiate between active vs preexisting disease.

We found that eating disorders were associated with an increased relative risk of several pregnancy and neonatal complications (which varied between the subtypes and differed in strength depending on active or previous disease) compared with not having an eating disorder. Our finding of an increased risk of developing hyperemesis gravidarum among women with any eating disorder has been described previously,6,8 but we could extend these results and differentiate between a higher RR for women with an active eating disorder. Whether the observed increased occurrence of hyperemesis gravidarum in women with eating disorders reflects an actual increased risk (with potential shared pathophysiological risk factors) of the condition or is caused by misclassification owing to similarities between symptoms of eating disorders and hyperemesis remains unclear. Adjusting for psychiatric comorbidities decreased the RRs substantially, indicating that the association between maternal eating disorders and hyperemesis could be explained partly by psychiatric comorbidity. An increased occurrence of anemia in pregnant women with eating disorders has also been described previously6,7; we found a doubled risk for anemia in women with active anorexia nervosa or EDNOS, which could be associated with nutritional deficiency.

The increased risk of antepartum hemorrhage in patients with anorexia nervosa is, to our knowledge, a novel finding. The etiologic factors associated with antepartum hemorrhage were placenta previa, abruptio placentae, or unspecified bleeding. Restricting calorie intake constitutes one of the anorexia nervosa diagnostic criteria and consequently results in a malnourished state and low body weight. Nutritional biomarkers have been demonstrated to be significantly lower in women with active or previous anorexia nervosa.18 The pathophysiological mechanisms of both placenta previa and abruptio placentae are poorly defined, making it difficult to determine the cause for the association between anorexia nervosa and these conditions. However, women who are underweight before pregnancy have been shown to be at increased risk of abruptio placentae.19,20 Furthermore, abruptio placentae has been associated with certain vitamin and mineral deficiencies.21,22,23 Thus, one might hypothesize that anorexia nervosa–associated malnutrition impairs the placental trophoblastic invasion, which in turn might facilitate abruptio placentae. Malnutrition is also associated with an increased risk of infection, and chorioamnionitis is a well-established risk factor for abruptio placentae.24 More important, there is an association between nutritional status and the coagulation system. Anorexia nervosa has been associated with thrombocytopenia,25 and weight loss has been associated with reduction of certain coagulation factors, leading to fibrinolysis.

Our findings of an increased risk of preterm birth and SGA neonates for women with eating disorders have been reported previously.4,6,7,8,9 Likewise, 1 study has reported that women with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa are at increased risk of delivering neonates with microcephaly.6,26 We found that the risk was most pronounced for women with active anorexia nervosa, who experienced a doubled risk of preterm and SGA birth and a 3-fold increased risk of delivering neonates with microcephaly. There were also significantly increased risks of preterm birth, SGA birth, and microcephaly for women with previous anorexia nervosa. An increased risk of preterm birth and microcephaly was also seen for women with the other eating disorder subtypes. The pathophysiological mechanisms behind these observations are not known, but there are several hypothetical explanations. Maternal-fetal stress is a suggested potential mechanism for preterm birth,27,28 and the stress hormone cortisol has been found to be increased in women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Furthermore, high levels of cortisol have been associated with microcephaly among women with anorexia nervosa.18 An inadequate diet throughout pregnancy with subsequent nutritional deficiencies would doubtless be associated with fetal growth restriction, and certain nutritional deficiencies have also been associated with an increased risk of preterm birth.29 There are other potential explanations behind the observed associations between maternal eating disorder and adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, but there is also a set of potential study limitations to consider when interpreting the results. Our approach of identifying population-based exposed and unexposed women and covariates of interest using nationwide register sources, with prospectively collected data, naturally limits the risk of introducing selection and/or recall biases. The validity of the different eating disorder diagnoses has not been assessed in the Swedish NPR, but many other diagnoses have been proven to have high validity.15 We attempted to increase the validity by requiring a registered diagnosis in at least 2 time points and at preselected specialized clinics. One might argue that our exposure definition introduces selection bias by identifying patients with more severe disease, which in that case would lead to an overestimation of the reported RRs. Several epidemiologic studies indicate that many individuals fulfill the diagnostic criteria of eating disorder and do not seek health care and thereby go undetected.30 Consequently, participants with a registered eating disorder diagnosis would not be fully representative of the general population. In the sensitivity analysis in which the exposure definition was changed to 1 or more registered diagnoses, the results remained similar to those of the main analysis. Presumably, the exposed cohorts consist of individuals with a spectrum of disease severity, and our exposure definition could be readily transferred to clinical practice, where only women with overt eating disorders (ongoing or previous) will be identified. We could adjust all our analyses for important potential confounders such as age, parity, smoking, and birth year, but there might still be unmeasured factors and residual confounding that could distort our observed associations. Early-pregnancy BMI could be considered a mediator between exposure and the outcomes and was therefore not adjusted for. For descriptive purposes, we performed a sensitivity analysis including only participants with a normal BMI, which did not affect our results. More important, this analysis is insufficient to determine whether BMI is mediating the outcome. However, of the 3 eating disorders, only anorexia nervosa was associated with being underweight, and eating disorders are present across all BMI categories. Other and more specific measurements of nutritional status, including maternal weight gain throughout pregnancy, would be of interest to investigate as potential mediators. Our study was conducted using Swedish national health registers, reflecting Swedish health care. We do, however, think that our findings should be generalizable to similar populations with similar demographic factors and health care settings.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that women with eating disorders are at increased risk of developing pregnancy complications and delivering preterm infants with increased risk of being SGA and/or with microcephaly. Women with eating disorders should therefore be recognized as a high-risk population among pregnant women. From a clinical point of view, these findings emphasize the importance of developing a reliable antenatal routine enabling identification of women with ongoing or previous eating disorders and considering extended pregnancy screening. Important future research tasks should focus on identifying mechanisms behind the impaired outcomes for women with eating disorders as well as addressing long-term outcomes.

eTable 1. Maternal Baseline Characteristics Among Unexposed and Exposed Women With Eating Disorder by Subtype (Where Exposure Definition is Changed to ≥1 Registered ED-Diagnosis Prior to Pregnancy)

eTable 2. Pregnancy Complications Among Women With Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorders: Sub-Analysis in Which Exposure-Definition is Changed to ≥1 Registered ED-Diagnosis

eTable 3. Outcomes Among Women With Anorexia Nervosa Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder in Women With a Normal Early Pregnancy BMI

eTable 4. Outcomes Among Women With Bulimia Nervosa Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder in Women With a Normal Early Pregnancy BMI

eTable 5. Outcomes Among Women With Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder in Women With a Normal Early Pregnancy BMI

eTable 6. Multivariate Analysis of Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes in Women With Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder: Adjusted for a History of Anxiety and Depressive Disorder

References

- 1.Schaumberg K, Welch E, Breithaupt L, et al. The science behind the academy for eating disorders’ nine truths about eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25(6):432-450. doi: 10.1002/erv.2553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipfel S, Giel KE, Bulik CM, Hay P, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(12):1099-1111. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00356-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currin L, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Jick H. Time trends in eating disorder incidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:132-135. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sollid CP, Wisborg K, Hjort J, Secher NJ. Eating disorder that was diagnosed before pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):206-210. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00900-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasternak Y, Weintraub AY, Shoham-Vardi I, et al. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in women with eating disorders. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(1):61-65. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koubaa S, Hällström T, Lindholm C, Hirschberg AL. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women with eating disorders [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(5):1217]. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):255-260. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000148265.90984.c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linna MS, Raevuori A, Haukka J, Suvisaari JM, Suokas JT, Gissler M. Pregnancy, obstetric, and perinatal health outcomes in eating disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(4):392.e1-392.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan JF, Lacey JH, Chung E. Risk of postnatal depression, miscarriage, and preterm birth in bulimia nervosa: retrospective controlled study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):487-492. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221265.43407.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, et al. Eating disorders among delivery hospitalizations: prevalence and outcomes. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(9):1523-1528. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson HJ, Zerwas S, Torgersen L, et al. Maternal eating disorders and perinatal outcomes: a three-generation study in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(5):552-564. doi: 10.1037/abn0000241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekéus C, Lindberg L, Lindblad F, Hjern A. Birth outcomes and pregnancy complications in women with a history of anorexia nervosa. BJOG. 2006;113(8):925-929. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micali N, De Stavola B, dos-Santos-Silva I, et al. Perinatal outcomes and gestational weight gain in women with eating disorders: a population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2012;119(12):1493-1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659-667. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cnattingius S, Ericson A, Gunnarskog J, Källén B. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand J Soc Med. 1990;18(2):143-148. doi: 10.1177/140349489001800209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cnattingius S, Norman M, Granath F, Petersson G, Stephansson O, Frisell T. Apgar score components at 5 minutes: risks and prediction of neonatal mortality. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2017;31(4):328-337. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsál K, Persson PH, Larsen T, Lilja H, Selbing A, Sultan B. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85(7):843-848. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koubaa S, Hällström T, Brismar K, Hellström PM, Hirschberg AL. Biomarkers of nutrition and stress in pregnant women with a history of eating disorders in relation to head circumference and neurocognitive function of the offspring. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:318. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0741-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsch AB, Lynch O, Alio AP, Salihu HM, Spellacy WN. Increased risk of placental abruption in underweight women. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(3):235-240. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1239490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aliyu MH, Alio AP, Lynch O, Mbah A, Salihu HM. Maternal pre-gravid body weight and risk for placental abruption among twin pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(9):745-750. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumann P, Blackwell SC, Schild C, Berry SM, Friedrich HJ. Mathematic modeling to predict abruptio placentae. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(4):815-822. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray JG, Laskin CA. Folic acid and homocyst(e)ine metabolic defects and the risk of placental abruption, pre-eclampsia and spontaneous pregnancy loss: a systematic review. Placenta. 1999;20(7):519-529. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollset SE, Refsum H, Irgens LM, et al. Plasma total homocysteine, pregnancy complications, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(4):962-968. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.4.962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ananth CV, Oyelese Y, Srinivas N, Yeo L, Vintzileos AM. Preterm premature rupture of membranes, intrauterine infection, and oligohydramnios: risk factors for placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):71-77. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000128172.71408.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hütter G, Ganepola S, Hofmann WK. The hematology of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(4):293-300. doi: 10.1002/eat.20610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koubaa S, Hällström T, Hagenäs L, Hirschberg AL. Retarded head growth and neurocognitive development in infants of mothers with a history of eating disorders: longitudinal cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120(11):1413-1422. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz RJ, Fullerton J, Dudley DJ. The interrelationship of maternal stress, endocrine factors and inflammation on gestational length. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58(6):415-428. doi: 10.1097/01.OGX.0000071160.26072.DE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadhwa PD, Culhane JF, Rauh V, Barve SS. Stress and preterm birth: neuroendocrine, immune/inflammatory, and vascular mechanisms. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5(2):119-125. doi: 10.1023/A:1011353216619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casanueva E, Ripoll C, Meza-Camacho C, Coutiño B, Ramírez-Peredo J, Parra A. Possible interplay between vitamin C deficiency and prolactin in pregnant women with premature rupture of membranes: facts and hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64(2):241-247. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt U, Adan R, Böhm I, et al. Eating disorders: the big issue. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(4):313-315. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00081-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Maternal Baseline Characteristics Among Unexposed and Exposed Women With Eating Disorder by Subtype (Where Exposure Definition is Changed to ≥1 Registered ED-Diagnosis Prior to Pregnancy)

eTable 2. Pregnancy Complications Among Women With Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorders: Sub-Analysis in Which Exposure-Definition is Changed to ≥1 Registered ED-Diagnosis

eTable 3. Outcomes Among Women With Anorexia Nervosa Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder in Women With a Normal Early Pregnancy BMI

eTable 4. Outcomes Among Women With Bulimia Nervosa Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder in Women With a Normal Early Pregnancy BMI

eTable 5. Outcomes Among Women With Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder in Women With a Normal Early Pregnancy BMI

eTable 6. Multivariate Analysis of Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes in Women With Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified Compared With Women Free of Eating Disorder: Adjusted for a History of Anxiety and Depressive Disorder