This cohort study assesses the long-term functional, psychological, emotional, and social outcomes of firearm injuries on survivors.

Key Points

Question

What are the long-term physical, mental, emotional, and social outcomes among individuals with gunshot wounds?

Findings

In this cohort study of patient-reported outcome measures, 183 young adult patients (median age, 27 years) who survived gunshot wounds (median time from injury, 5.9 years) reported worse physical and mental health compared with the general population, 48.6% had positive screen findings for probable posttraumatic stress disorder, and unemployment and substance use increased by 14.3% and 13.2%, respectively, after injury.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the outcomes of firearm injury reach far beyond mortality statistics; survivors of gunshot wounds may benefit from early identification and the initiation of long-term, multidisciplinary longitudinal care to improve recovery.

Abstract

Importance

The outcomes of firearm injuries in the United States are devastating. Although firearm mortality and costs have been investigated, the long-term outcomes after surviving a gunshot wound (GSW) remain unstudied.

Objective

To determine the long-term functional, psychological, emotional, and social outcomes among survivors of firearm injuries.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cohort study assessed patient-reported outcomes among GSW survivors from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2017, at a single urban level I trauma center. Attempts were made to contact all adult patients (aged ≥18 years) discharged alive during the study period. A total of 3088 patients were identified; 516 (16.7%) who died during hospitalization and 45 (1.5%) who died after discharge were excluded. Telephone contact was made with 263 (10.4%) of the remaining patients, and 80 (30.4%) declined study participation. The final study sample consisted of 183 participants. Data were analyzed from June 1, 2018, through June 20, 2019.

Exposures

A GSW sustained from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Scores on 8 Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) instruments (Global Physical Health, Global Mental Health, Physical Function, Emotional Support, Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, Pain Intensity, Alcohol Use, and Severity of Substance Use) and the Primary Care PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder) Screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.

Results

Of the 263 patients who survived a GSW and were contacted, 183 (69.6%) participated. Participants were more likely to be admitted to the hospital compared with those who declined (150 [82.0%] vs 54 [67.5%]; P = .01). Participants had a median time from GSW of 5.9 years (range, 4.7-8.1 years) and were primarily young (median age, 27 years [range, 21-36 years]), black (168 [91.8%]), male (169 [92.3%]), and employed before GSW (pre-GSW, 139 [76.0%]; post-GSW, 113 [62.1%]; decrease, 14.3%; P = .004). Combined alcohol and substance use increased by 13.2% (pre-GSW use, 56 [30.8%]; post-GSW use, 80 [44.0%]). Participants had mean (SD) scores below population norms (50 [10]) for Global Physical Health (45 [11]; P < .001), Global Mental Health (48 [11]; P = .03), and Physical Function (45 [12]; P < .001) PROMIS metrics. Eighty-nine participants (48.6%) had a positive screen for probable PTSD. Patients who required intensive care unit admission (n = 64) had worse mean (SD) Physical Function scores (42 [13] vs 46 [11]; P = .045) than those not requiring the intensive care unit. Survivors no more than 5 years after injury had greater PTSD risk (38 of 63 [60.3%] vs 51 of 119 [42.9%]; P = .03) but better mean (SD) Global Physical Health scores (47 [11] vs 43 [11]; P = .04) than those more than 5 years after injury.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s results suggest that the lasting effects of firearm injury reach far beyond mortality and economic burden. Survivors of GSWs may have negative outcomes for years after injury. These findings suggest that early identification and initiation of long-term longitudinal care is paramount.

Introduction

The effects of firearm violence in the United States are devastating. From 1999 to 2013, 462 043 US individuals were killed by firearms.1 The gun-related homicide rate in the United States is 25 times higher than in other high-income countries2 and appears to be increasing.3 In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that US firearm-related homicides reached their highest peak since tracking of these data began 40 years ago.4 The mean initial hospitalization costs related to firearm injuries are estimated at $735 million per year, with an increasing burden placed on taxpayers.5,6

Interest in characterizing long-term outcomes in survivors of trauma has been growing7,8,9 because many recognize that the effects of injury extend well beyond mortality, economic burden, and functional measurements at hospital discharge.10 Previous work focusing primarily on patients with blunt trauma demonstrated long-term impairments in physical function, activities of daily living, and inability to work as well as increased risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression.11,12 One particularly ill-defined population, however, consists of the 70 000 annual survivors of firearm injuries.13,14 Incomplete understanding of the long-term effects of gunshot wounds (GSWs) could be related to federal funding restrictions previously placed on firearm injury research by the 1996 Dickey Amendment.15,16,17 Few studies to our knowledge have evaluated this population specifically, although evaluation of a small cohort of survivors of emergency department thoracotomy found that 25% had screen findings positive for PTSD, and many reported postinjury unemployment and substance use.18 A deeper understanding of the long-term outcomes of firearm injuries is needed to provide more appropriate and tailored care to this unique patient population.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), which rely solely on individual reports of health,19 have increasingly been used to evaluate the long-term effects of injury.12,19,20,21 Using these tools, we sought to determine the long-term functional, psychological, emotional, and social outcomes of firearm injuries among survivors and hypothesized that being shot has a lasting and detrimental outcome in this population.

Methods

After University of Pennsylvania institutional review board approval for this cohort study, we attempted to contact all adult patients (aged ≥18 years) discharged alive from our urban, level I trauma center after sustaining GSWs from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2017. Patients were contacted by telephone using all numbers identified in the trauma registry and medical record. If a patient was not reached on the first call, 2 additional calls were made on different days and at different times to maximize opportunities for contact. Once contacted, participants provided verbal informed consent for the study, and demographic and injury-related variables were assessed using a standardized script. Because of recidivism, we ensured that no single patient participated more than once. If a participant was shot on more than 1 occasion, only data from the most recent injury were used. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Participants were evaluated with 8 Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) instruments, each scored on a unique Likert scale. The PROMIS Global Physical Health (version 1.2) and Global Mental Health (version 1.2) instruments measured overall physical and mental health, whereas the PROMIS Short Form Physical Function 8b (version 2.0) instrument assessed self-reported physical capabilities. The PROMIS Short Form Emotional Support 4a (version 2.0) instrument evaluated perceptions of being cared for and valued. The PROMIS Short Form Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities 4a (version 2.0) instrument assessed participation in social roles and activities. The PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a (version 1.0) instrument measured daily pain levels. The PROMIS Short Form Alcohol Use 7a (version 1.0) and Short Form Severity of Substance Use 7a (version 1.0) instruments evaluated alcohol and substance use during the preceding 30 days and were applicable only for current alcohol or substance users. Raw PROMIS scores were converted to standardized T scores using PROMIS conversion tables.22 Patients also completed the Primary Care PTSD Screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (PC-PTSD-5) to screen for PTSD. Preinjury work status and drug and alcohol use were also assessed. Participants were offered primary care and mental health resources at the completion of each survey.

Demographic and clinical variables were compared between study participants and those who declined participation or could not be contacted by telephone. Demographic and clinical variables and long-term outcome measures were compared with respect to elapsed time from injury and need for hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Outcomes were compared between participants with a GSW on more than 1 occasion and those with only 1 GSW. For each PROMIS instrument, participants’ mean T scores were compared with calibrated reference populations (reference mean [SD] T score, 50 [10]) using 1-sample t tests. The comparator reference group for each PROMIS instrument is the US general population, with the exception of the Alcohol Use (reference includes general population and patients with chronic illnesses), Pain Intensity (reference includes general population and patients in pain support groups), and Severity of Substance Use (applicable only to users of substances other than alcohol and prescription medications) instruments. Importantly, Global Physical Health, Global Mental Health, Physical Function, Emotional Support, and Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities instrument T scores of greater than 50 indicate a more favorable outcome than the reference population. Conversely, Pain Intensity, Alcohol Use, and Severity of Substance Use instrument T scores of less than 50 are considered more favorable than the reference population.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from June 1, 2018, through June 20, 2019. We used the Mann-Whitney test to compare medians between groups, and the 1-sample t test was used for normally distributed data. We performed χ2 and Fisher exact tests to compare categorical variables, represented as number (percentage). We used SPSS, version 24 (IBM Corp) for all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Overall, 3088 patients were treated for GSWs at our institution from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2017. Fifty-nine GSWs (1.9%) resulted from intentional or unintentional self-harm, and 3029 (98.1%) resulted from assault. Patients who died during hospitalization (516 [16.7%]) or after discharge (45 [1.5%]) were excluded. We telephoned the remaining 2527 patients and made contact with 263 (10.4%); 80 (30.4%) declined study participation. Our final study sample consisted of 183 participants, all injured by assault (eFigure in the Supplement). We were unable to contact any individual who sustained a GSW from intentional or unintentional self-harm.

Demographic, clinical, and social characteristics were assessed (Table 1). The participant group was primarily young (median age at GSW, 27 years [range, 21-36 years]), black (168 [91.8%]), and male (169 men [92.3%] vs 14 women [7.7%]) and required hospital admission (150 [82.0%]). The median elapsed time from GSW was 5.9 years (range, 4.7-8.1 years). Nine participants (4.9%) were shot on more than 1 occasion. Reported employment rates decreased 14.3% after injury (pre-GSW, 139 [76.0%]; post-GSW, 113 [62.1%], with 1 patient missing post-GSW data; P = .004), whereas overall combined alcohol and drug use increased 13.2% (pre-GSW use, 56 [30.8%]; post-GSW use, 80 [44.0%] [with 1 patient missing data at both times]; P = .009).

Table 1. Demographics, Clinical, and Social Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Study Participants (N = 183) | Respondents Who Declined Participation (n = 80) | P Valuea | Population Unable to Contact (n = 2264)b | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at GSW, median (IQR), y | 27 (21-36) | 26 (21-34) | .71 | 25 (21-32) | .06 |

| Time from GSW, median (IQR), y | 5.9 (4.7-8.1) | 7.7 (2.6-8.8) | .54 | 5.6 (2.8-8.0) | .02 |

| Race, No. (%) | |||||

| Black | 168 (91.8) | 66 (82.5) | .07 | 2071 (91.4) | .74 |

| White | 13 (7.1) | 11 (13.8) | 128 (5.7) | ||

| Other | 2 (1.1) | 3 (3.8) | 28 (1.2) | ||

| Male, No. (%) | 169 (92.3) | 74 (92.5) | .97 | 2101 (92.8) | .82 |

| ISS, median (IQR)d | 9 (1-17) | 7 (1-19) | .50 | 5 (1-14) | .054 |

| Hospital admission, No. (%) | 150 (82.0) | 54 (67.5) | .01 | 1536 (67.8) | <.001 |

| Hospital LOS, median (IQR), d | 5 (2-12) | 6 (4-14) | .23 | 6 (2-11) | .68 |

| ICU admission, No. (%) | 64 (35.0) | 29 (36.3) | .84 | 694 (30.7) | .22 |

| ICU LOS, median (IQR), d | 3.5 (1-14) | 4 (1-12) | .98 | 2 (1-5) | .02 |

| Employment, No. (%) | |||||

| Before GSW | 139 (76.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| After GSWe | 113 (62.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Time to employment return, median (IQR), mo | 4.5 (1.5-12) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Alcohol and/or substance use, No. (%)e | |||||

| Before GSW | 56 (30.8) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| After GSW | 80 (44.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: GSW, gunshot wound; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, Injury Severity Score; LOS, length of stay; NA, not applicable.

Compares participants with respondents who declined participation using Mann-Whitney test to compare medians and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical data.

Owing to missing data for some individuals, percentages may not total 100.

Compares participants with the population we were unable to contact using Mann-Whitney test to compare medians and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical data.

Scores range from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating more severe injury.

Available in 182 participants.

To assess for potential selection bias, participants were compared with those who declined and those who were unreachable (Table 1). We found no differences between participants and nonparticipants with respect to age at GSW, race, sex, Injury Severity Score (ISS [range, 0-75, with higher scores indicating more severe injury]), hospital length of stay, and need for ICU admission. Participants were more likely to require hospital admission (150 [82.0%]) compared with those who declined (54 of 80 [67.5%]; P = .01) and those who were unreachable (1536 of 2264 [67.8%]; P < .001). Participants had longer elapsed time from GSW (median, 5.9 years [range, 4.7-8.1 years]) compared with the population that we could not contact (median, 5.6 years [range, 2.8-8.0 years]; P = .02) and a shorter elapsed time compared with those who refused participation (median, 7.7 years [range, 2.6-8.8 years]; P = .54), although the latter comparison did not reach statistical significance. No differences were noted in any PROMIS metrics or PTSD rates between participants who were shot on more than 1 occasion and those shot only once.

Compared with the US general population, participants reported worse function in the domains of Global Physical Health (mean [SD] score, 44 [11] vs 50 [10]; P < .001), Physical Function (mean [SD] score, 45 [12] vs 50 [10]; P < .001), and Global Mental Health (mean [SD] score, 48 [11] vs 50 [10]; P = .03). Scores for Pain Intensity (mean [SD] score, 48 [12]; P = .04), Alcohol Use (mean [SD] score, 44 [8]; P < .001), and Severity of Substance Use (mean [SD] score, 45 [6]; P = .001) were better in study participants than in their respective reference populations (Table 2). Combined alcohol and substance use increased by 13.2% (pre-GSW use, 56 [30.8%]; post-GSW use, 80 [44.0%]).

Table 2. Comparison of PROMIS Metrics Between Participants and Reference Populations.

| Instrumenta | Mean (SD) Score | P Valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Participants (n = 183) | Reference Populationb | ||

| Global Physical Healthd | 44 (11) | 50 (10) | <.001 |

| Global Mental Health | 48 (11) | 50 (10) | .03 |

| Physical Function | 45 (12) | 50 (10) | <.001 |

| Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities | 51 (12) | 50 (10) | .18 |

| Emotional Support | 54 (10) | 50 (10) | <.001 |

| Pain Intensity | 48 (12) | 50 (10) | .04 |

| Alcohol Usee | 44 (8) | 50 (10) | <.001 |

| Severity of Substance Usef | 45 (6) | 50 (10) | .001 |

Abbreviation: PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

PROMIS T scores above the reference population level for Global Physical Health, Global Mental Health, Physical Function, Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, and Emotional Support are more favorable; T scores below the reference population level for Pain Intensity, Alcohol Use, and Severity of Substance Use are more favorable.

The reference population is the US general population with the exception of Alcohol Use (which includes a clinical sample of patients with chronic illnesses and applies only to current users), Pain Intensity (which includes the general population and those in pain support groups), and Severity of Substance Use (which applies only to patients who have used a substance other than alcohol or prescription medications).

Calculated using 1-sample t test.

Data were missing for 2 participants.

Includes 64 participants who reported current use of alcohol.

Includes 24 participants who reported current use of a substance other than alcohol or prescription medications.

Study patients were assessed based on time from injury (≤5 vs >5 years) (Table 3). There were no differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between these groups for rates of alcohol (18 of 63 [28.6%] vs 46 of 120 [38.3%]; P = .19) and substance (11 of 63 [17.5%] vs 13 of 120 [10.8%]; P = .21) use in the preceding 30 days. Participants with more than 5 years since injury reported worse Global Physical Health (mean [SD] score, 43 [11] vs 47 [11]; P = .04) but were less likely to have a positive screen finding for probable PTSD (51 of 119 [42.9%] vs 38 of 63 [60.3%]; P = .03). There were no differences between groups in the other PROMIS instrument scores.

Table 3. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and PROMIS Metrics Based on Time From Injury.

| Characteristic or Metric | Time from GSW | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 y (n = 63) | >5 y (n = 120) | ||

| Age at GSW, median (IQR), y | 28 (21-37) | 26 (21-35) | .33 |

| ISS, median (IQR)b | 9 (1-17) | 9 (1-17) | .11 |

| Hospital admission, No. (%) | 56 (88.9) | 94 (78.3) | .08 |

| Hospital LOS, median (IQR), d | 4.5 (2-10) | 6 (3-17) | .52 |

| ICU admission, No. (%) | 24 (38.1) | 40 (33.3) | .52 |

| ICU LOS, median (IQR), d | 3 (1-14) | 4 (1-14) | .94 |

| PROMIS instrument, mean (SD) T scorec | |||

| Global Physical Healthd | 47 (11) | 43 (11) | .04 |

| Global Mental Health | 50 (11) | 47 (12) | .18 |

| Physical Function | 46 (11) | 46 (12) | .67 |

| Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities | 51 (11) | 52 (12) | .54 |

| Emotional Support | 54 (10) | 54 (11) | .80 |

| Pain Intensity | 46 (11) | 49 (13) | .08 |

| Alcohol Usee | 45 (8) | 43 (8) | .43 |

| Severity of Substance Usef | 45 (6) | 46 (6) | .69 |

| Probable PTSD, No. (%)g | 38 (60.3) | 51 (42.9) | .03 |

Abbreviations: GSW, gunshot wound; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, Injury Severity Score; LOS, length of stay; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Calculated using Mann-Whitney test to compare medians and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical data.

Scores range from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating more severe injury.

PROMIS T scores above the reference population level for Global Physical Health, Global Mental Health, Physical Function, Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, and Emotional Support are more favorable; T scores below the reference population level for Pain Intensity, Alcohol Use, and Severity of Substance Use are more favorable.

Data were missing for 2 participants in the group with 5 or less years from GSW.

Includes 18 participants with no more than 5 years since GSW and 46 with more than 5 years since GSW who reported current use of alcohol.

Includes 11 participants with no more than 5 years since GSW and 13 with more than 5 years since GSW who reported current use of a substance other than alcohol or prescription medicine.

Based on Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5. Data were missing for 1 participant with more than 5 years since GSW.

Participants were compared with respect to hospital (Table 4) and ICU (eTable in the Supplement) admissions. Patients requiring hospital admission had a higher ISS (median, 10 [range, 5-19] vs 1 [1-1]; P < .001) and scored worse on the domains of Global Physical Health (mean [SD] score, 44 [11] vs 49 [11]; P = .01), Physical Function (mean [SD] score, 44 [12] vs 49 [10]; P = .01), and Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities (mean [SD] score, 50 [12] vs 56 [9]; P = .01). Rates of alcohol (51 of 150 [34.0%] vs 13 of 33 [39.4%]; P = .56) and substance (19 of 150 [12.7%] vs 5 of 33 [15.2%]; P = .70) use did not differ between groups, but severity of alcohol use as measured by the Alcohol Use PROMIS instrument was worse in patients requiring hospital admission (mean [SD] score, 44 [9] vs 40 [4]; P = .03). Admitted patients were more likely to have screen findings positive for PTSD (78 of 149 [52.3%] vs 11 of 33 [33.3%]; P = .048) compared with participants who were discharged from the emergency department. Participants requiring ICU admission had a greater ISS (median, 19 [range, 12-28] vs 9 [range, 2-10]; P < .001) and more prolonged hospital LOS (median, 14.5 days [range, 7.0-25.8 days] vs 3.0 days [range, 1.0-5.0 days]; P < .001) compared with patients not requiring ICU care. Despite similar elapsed time from injury, patients who required ICU admission reported worse Physical Function (mean [SD] score, 42 [13] vs 46 [11]; P = .045) compared with those not requiring ICU admission. There were no differences between these 2 groups with respect to the other PROMIS metrics or rates of alcohol (20 of 64 [31.3%] vs 31 of 86 [36.0%]; P = .54) and substance (7 of 64 [10.9%] vs 12 of 86 [14.0%]; P = .58) use in the preceding 30 days.

Table 4. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and PROMIS Metrics Based on Hospital Admission.

| Characteristic or Metric | Hospital Admission (n = 150) | Discharged From Emergency Department (n = 33) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at GSW, median (IQR), y | 27 (21-36) | 27 (20-33) | .32 |

| ISS, median (IQR)b | 10 (5-19) | 1 (1-1) | <.001 |

| Time from GSW, median (IQR), y | 6 (5-8) | 6 (5-9) | .13 |

| PROMIS instrument, mean (SD) T scorec | |||

| Global Physical Healthd | 44 (11) | 49 (11) | .01 |

| Global Mental Health | 47 (12) | 51 (10) | .09 |

| Physical Function | 44 (12) | 49 (10) | .01 |

| Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities | 50 (12) | 56 (9) | .01 |

| Emotional Support | 54 (11) | 56 (9) | .28 |

| Pain Intensity | 49 (12) | 45 (12) | .11 |

| Alcohol Usee | 44 (9) | 40 (4) | .03 |

| Severity of Substance Usef | 46 (6) | 43 (5) | .46 |

| Probable PTSD, No. (%)g | 78 (52.3) | 11 (33.3) | .048 |

Abbreviations: GSW, gunshot wound; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, Injury Severity Score; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Calculated using the Mann-Whitney test to compare medians and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical data.

Scores range from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating more severe injury.

PROMIS T scores above the reference population level for Global Physical Health, Global Mental Health, Physical Function, Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, and Emotional Support are more favorable; T scores below the reference population level for Pain Intensity, Alcohol Use, and Severity of Substance Use are more favorable. Alcohol Use and Severity of Substance Abuse are applicable only to current users.

Data were missing for 1 patient with hospital admission and 1 patient discharged from the emergency department.

Includes 51 participants admitted to the hospital and 13 discharged from the emergency department who reported current use of alcohol.

Includes 19 participants admitted to the hospital and 5 discharged from the emergency department who reported current use of a substance other than alcohol or prescription medications.

Based on Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5. Data were missing for 1 participant admitted to the hospital.

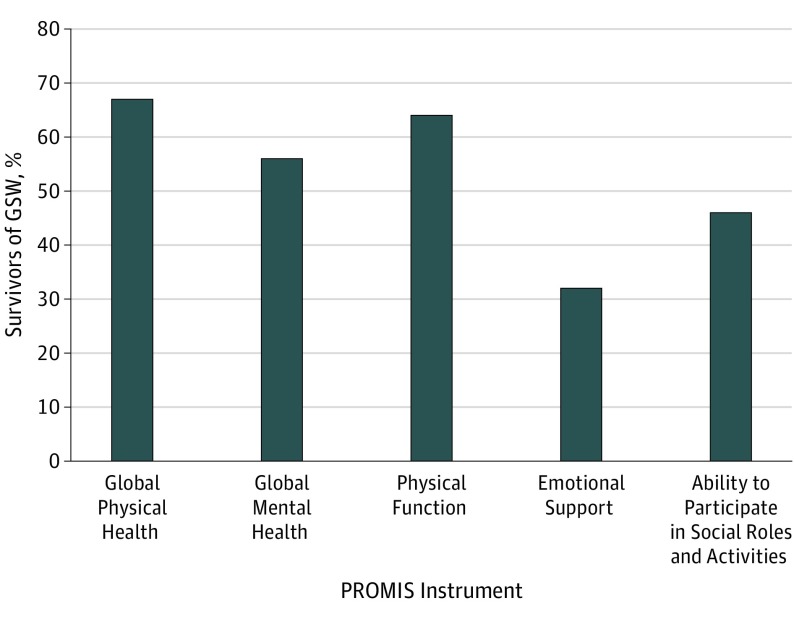

Overall, a significant number of participants reported worse outcomes compared with the US general population on the PROMIS domains of Global Physical Health (122 of 181 [67.4%]), Global Mental Health (102 of 183 [55.7%]), Physical Function (118 of 183 [64.5%]), Emotional Support (58 of 183 [31.7%]), and Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities (85 of 183 [46.4%]) (Figure). When compared with their respective reference populations, participants also reported worse scores in Pain Intensity (86 of 183 [47.0%]), Alcohol Use (14 of 64 [21.9%]), and Severity of Substance Use (6 of 24 [25.0%]) domains. Eighty-nine of the 148 participants (56.1%) who considered their GSW a traumatic event had screen findings for probable PTSD based on the PC-PTSD-5 score (48.6% of the overall population).

Figure. Long-term Physical, Mental, and Social Outcome Assessment Battery.

Data are expressed as the percentage of survivors of gunshot wounds (GSWs) with Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) instrument assessment scores below population norms.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that survivors of GSWs experience adverse physical and mental function outcomes years after being shot. Moreover, these consequences do not appear to improve with time, nor are they limited to those with critical injuries requiring hospital or ICU admission.

Long-term outcomes after traumatic injury have been evaluated using a number of metrics described elsewhere.9,23 Although some instruments are disease specific, others allow for evaluation of outcomes across diverse populations.9,23 Patient-reported outcome measures were designed to evaluate patients’ views of symptoms as opposed to those of physicians or other parties.19,24 Although PROMs require direct communication with the participants, 1 study of patients with trauma primarily due to blunt injuries found that a significant number could be contacted to 10 years after injury using an aggressive follow-up strategy.25 In addition, outcome measurements appear to be consistent between in-person and telephone interviews.26 In the present study, participants were evaluated with a battery of PROMIS metrics. These proprietary PROMs are simple, efficient, flexible, and precise instruments used to measure generic symptoms and function across a wide range of populations. To our knowledge, PROMIS instruments have not been used specifically in patients with GSWs, although they have been used extensively in patients with orthopedic problems and those with traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries, for which they have been shown to perform better than traditional metrics.19,20,21,22,27,28,29,30 Most participants in the present study reported worse function in the PROMIS domains of Global Physical Health (67.4%), Global Mental Health (55.7%), and Physical Function (64.5%) compared with the general population. These impairments appear to persist for several years; outcomes in the domain of Global Physical Health were worse in those more than 5 years since injury, and there were no differences in 7 of 8 PROMIS metrics when comparing participants based on time from injury. These findings are consistent with other studies evaluating long-term outcomes after injury, which have involved primarily blunt mechanisms. In a study by Gabbe et al31 of 236 patients with blunt trauma 6 months after injury, 69% of the 221 patients living in the community required continued health care services, most commonly physical therapy, medical specialist care, occupational therapy, mental health care, and home help. In another study of 2757 patients with primarily blunt trauma (94%) in Australia,11 the participants reported problems with mobility (37%), self-care (21%), usual activities (47%), pain or discomfort (50%), and anxiety or depression (41%) as long as 36 months after injury. Of interest, participants in that study injured by penetrating mechanisms were more likely to be lost to follow-up. Haider et al12 followed up 1736 participants (94% blunt mechanism) from 6 to 12 months after injury. Thirty-seven percent of patients reported physical limitations in at least 1 activity of daily living, and participants as a whole reported worse outcomes than the general population with respect to physical health. Although almost 50% reported that their injuries were “hard to deal with,” there was no difference in overall mental health. This finding differs from our results, in which most of the participants reported worse scores in Global Mental Health. With respect to patients with penetrating trauma, 1 study of 16 survivors of emergency department thoracotomy (65% with GSWs and 35% with stab wounds)18 found that 81% were freely mobile and functional at baseline and 75% had normal cognition, seemingly more favorable outcomes compared with our population. In addition, patients in our study reported better outcomes compared with their respective reference populations on the domains of Emotional Support and Pain Intensity. One possible explanation is that the PROMIS reference population for Pain Intensity includes individuals in pain support groups.

Severity of injury also appears to be associated with long-term outcomes. We analyzed injury severity by comparing participants with respect to the need for hospital and ICU admission. Patients admitted to the hospital reported worse outcomes in physical function and social roles compared with those discharged from the emergency department, and patients admitted to the ICU reported worse physical function compared with those not requiring ICU care. Although the present study focuses solely on markedly underreported patients with GSWs and more prolonged time from injury, our results are consistent with prior studies that have evaluated long-term outcomes in patients primarily with blunt trauma requiring ICU admission. In one study,32 100 participants (19% with penetrating trauma) were contacted 3 years after injuries requiring ICU admission and reported less physical activity as well as difficulties returning to work. In another study of 101 patients with trauma and new ISS of greater than 15 (3.8% with penetrating trauma),33 participants reported worse physical and social functioning 2 years after injury when compared with the general population. Holtslag et al34 followed up 335 patients with trauma (ISS, >15) with multiple outcome measures 12 to 18 months after injury and described common limitations in mobility and daily activities. Other work supports these findings in patients with isolated orthopedic injuries.35 Together, these results suggest that need for ICU admission correlates with adverse physical functioning years after injury.

Postinjury unemployment and substance use are also common in survivors of trauma. In the present study, employment rates decreased by 14.3% after injury, with overall combined alcohol and substance use increasing by 13.2%. These changes are consistent with findings in previous reports in patients with blunt and penetrating trauma.12,18 In a study of more than 1700 severely injured patients,12 41% working before injury were unable to return to work. Among 16 survivors of emergency department thoracotomy (median, 59 months after injury),18 75% remained unemployed after injury, and 50% and 38% reported daily alcohol and drug use, respectively. Unfortunately, alcohol use is common among patients with trauma, with studies using the Abbreviated Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) concluding that as many as 30% of admitted patients use alcohol within 6 hours of injury.36 Of interest, participants in the present study who use alcohol and illicit substances reported less severe habits compared with reference populations, although, as mentioned previously, these references differ slightly from the general population. Underreporting of alcohol and substance abuse is common in surveys and may also play a role in these findings.37

The PC-PTSD-5 was first developed to assess the probability of PTSD in US veterans returning from combat and has since been used as a primary care screening tool.38,39,40 Eighty-nine participants (48.6%) in the present study had screening findings for probable PTSD using this instrument compared with a 6.8% lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the US general population.41 Unfortunately, survivors of trauma have been shown to have high rates of postinjury PTSD. In a study of more than 2700 patients with traumatic injury,42 21% had PTSD at 12 months after discharge, which was independently associated with significant functional impairments and inability to return to work. Holbrook et al43 evaluated outcomes in 401 adolescent (aged 12-19 years) survivors of trauma (5.7% GSWs) and found that 27% had a long-term risk of PTSD that significantly affected quality of life. Other studies12,40,44 have shown reported rates of PTSD ranging from 18% to 42% at 1 to 6 months after injury and 2% to 36% at 12 months after injury for survivors of traumatic injury and 48% of a small subgroup of patients with penetrating trauma. Investigators believe that PTSD is more common after penetrating injury.43,44,45,46 Although our follow-up duration was much longer than those of the above-mentioned reports, the rates of PTSD were greater as well, suggesting that GSW injuries are intensely traumatic and stressful to survivors. Also important, 33.3% of our study participants with seemingly minor physical injuries who were discharged from the emergency department had screen findings for probable PTSD. For comparison, in a study of survivors of emergency department thoracotomy (with obviously more critical injuries),18 only 25% of respondents had screen findings positive for PTSD. These findings have important implications for the thousands of patients with GSWs discharged from US emergency departments each year.

Limitations

We acknowledge our study limitations. Although most respondents participated when contacted, most patients with GSWs could not be contacted by telephone despite multiple attempts. Although we believe this strategy to be the best method to evaluate true long-term outcomes in this unstudied population, the possibility of selection bias should be recognized. To mitigate these concerns, study participants were compared with those survivors of GSWs who could not be contacted and those who declined participation. Owing to the volume of potential participants, multiple study personnel were involved in making telephone calls. Participants may have been influenced by subtle differences in interviewer intonation, tone, and cadence despite investigators using a standardized script and survey instruments. Our study sample consisted primarily of healthy young black men and may be dissimilar to the proprietary reference populations used in the PROMIS instruments. In addition, we did not control for variables such as educational level or socioeconomic status. Our findings may not be applicable to survivors of blunt trauma or to pediatric patients, 2 populations that merit ongoing study as well. Response bias may have influenced the survey results, especially for patients far removed from injury or those less willing to openly discuss sensitive topics. Finally, we were unable to contact patients who sustained injuries from intentional or unintentional self-harm, and our results may not be applicable to these populations.

Conclusions

Based on the results of this cohort study, we have implemented a program in our trauma clinic to prospectively identify and follow up survivors of firearm injury, thereby evaluating changes in PROMs over time and allowing for ongoing physical and mental health support. The long-term outcomes of firearm injury reach beyond mortality and economic burden. Although contacting survivors of GSWs several years after injury proved difficult, our results indicate that survivors experience long-term physical and psychological outcomes years after being shot. Furthermore, our results suggest a role for the initiation of long-term longitudinal care to improve physical, mental, and emotional recovery after firearm injury.

eFigure. Flow Diagram Detailing Study Population

eTable. Comparison of Demographic, Clinical, and PROMIS Metrics Based on ICU Admission

References

- 1.Resnick S, Smith RN, Beard JH, et al. Firearm deaths in America: can we learn from 462,000 lives lost? Ann Surg. 2017;266(3):432-440. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis AB, Gaudino JA, Soskolne CL, Al-Delaimy WK; International Network for Epidemiology in Policy (Formerly known as IJPC-SE) . The role of epidemiology in firearm violence prevention: a policy brief. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(4):1015-1019. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC WONDER: about underlying cause of death, 1999-2017. https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/saved/D76/D48F344. Published December 2018. Accessed December 01, 2018.

- 5.Coupet E Jr, Karp D, Wiebe DJ, Kit Delgado M. Shift in US payer responsibility for the acute care of violent injuries after the Affordable Care Act: implications for prevention. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(12):2192-2196. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.03.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitzer SA, Staudenmayer KL, Tennakoon L, Spain DA, Weiser TG. Costs and financial burden of initial hospitalizations for firearm injuries in the United States, 2006-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):770-774. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulger EM, Kuhls DA, Campbell BT, et al. Proceedings from the medical summit on firearm injury prevention: a public health approach to reduce death and disability in the US. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(4):415-430.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabbe BJ, Sutherland AM, Hart MJ, Cameron PA. Population-based capture of long-term functional and quality of life outcomes after major trauma: the experiences of the Victorian State Trauma Registry. J Trauma. 2010;69(3):532-536. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e5125b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Sutherland AM, et al. Functional measures at discharge: are they useful predictors of longer term outcomes for trauma registries? Ann Surg. 2008;247(5):854-859. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656d1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Cameron PA, et al. Long-term health status and trajectories of seriously injured patients: a population-based longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(7):e1002322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haider AH, Herrera-Escobar JP, Al Rafai SS, et al. Factors associated with long-term outcomes after injury: results of the Functional Outcomes and Recovery After Trauma Emergencies (FORTE) multicenter cohort study [published online Decembe 13, 2018]. Ann Surg. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, Annest JL. Firearm injuries in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;79:5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith RN, Seamon MJ, Kumar V, et al. Lasting impression of violence: retained bullets and depressive symptoms. Injury. 2018;49(1):135-140. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maa J, Darzi A. Firearm injuries and violence prevention—the potential power of a surgeon general’s report. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(5):408-410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1803295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masiakos PT, Warshaw AL. Stopping the bleeding is not enough. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):37-38. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alcorn T. Trends in research publications about gun violence in the United States, 1960 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):124-126. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller D, Kulp H, Maher Z, Santora TA, Goldberg AJ, Seamon MJ. Life after near death: long-term outcomes of emergency department thoracotomy survivors. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(5):1315-1320. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828c3db4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisala PA, Boulton AJ, Cohen ML, et al. Interviewer- versus self-administration of PROMIS® measures for adults with traumatic injury. Health Psychol. 2019;38(5):435-444. doi: 10.1037/hea0000685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung M, Stuart AR, Higgins TF, Saltzman CL, Kubiak EN. Computerized adaptive testing using the PROMIS Physical Function item bank reduces test burden with less ceiling effects compared with the Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment in orthopaedic trauma patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(8):439-443. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brodke DJ, Saltzman CL, Brodke DS. PROMIS for orthopaedic outcomes measurement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(11):744-749. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HealthMeasures Intro to PROMIS. http://healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis. Updated 2019. Accessed June 1, 2018.

- 23.Gabbe BJ, Williamson OD, Cameron PA, Dowrick AS. Choosing outcome assessment instruments for trauma registries. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(8):751-758. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.03.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pape HC, Zelle B, Lohse R, et al. Evaluation and outcome of patients after polytrauma—can patients be recruited for long-term follow-up [published correction appears in Injury. 2008;39(1):137]? Injury. 2006;37(12):1197-1203. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Samsa GP, Landsman PB. Are health-related quality-of-life measures affected by the mode of administration? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(2):135-140. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00556-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilde EA, Whiteneck GG, Bogner J, et al. Recommendations for the use of common outcome measures in traumatic brain injury research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(11):1650-1660.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):304-314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. ; PROMIS Cooperative Group . The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179-1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fries JF, Bruce B, Cella D. The promise of PROMIS: using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5)(suppl 39):S53-S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabbe BJ, Sutherland AM, Williamson OD, Cameron PA. Use of health care services 6 months following major trauma. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31(4):628-632. doi: 10.1071/AH070628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livingston DH, Tripp T, Biggs C, Lavery RF. A fate worse than death? long-term outcome of trauma patients admitted to the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):341-348. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a5cc34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soberg HL, Bautz-Holter E, Roise O, Finset A. Long-term multidimensional functional consequences of severe multiple injuries two years after trauma: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. J Trauma. 2007;62(2):461-470. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000222916.30253.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holtslag HR, van Beeck EF, Lindeman E, Leenen LP. Determinants of long-term functional consequences after major trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):919-927. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000224124.47646.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butcher JL, MacKenzie EJ, Cushing B, et al. Long-term outcomes after lower extremity trauma. J Trauma. 1996;41(1):4-9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199607000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vitesnikova J, Dinh M, Leonard E, Boufous S, Conigrave K. Use of AUDIT-C as a tool to identify hazardous alcohol consumption in admitted trauma patients. Injury. 2014;45(9):1440-1444. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livingston M, Callinan S. Underreporting in alcohol surveys: whose drinking is underestimated? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(1):158-164. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD): developments and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9-14. doi: 10.1185/135525703125002360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1206-1211. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steel JL, Dunlavy AC, Stillman J, Pape HC. Measuring depression and PTSD after trauma: common scales and checklists. Injury. 2011;42(3):288-300. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Institutes of Health Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd.shtml. Updated November 2017. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 42.Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, et al. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):429-437. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a6b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson JP. Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: new data on risk factors and functional outcome. J Trauma. 2005;58(4):764-769. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000159247.48547.7D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Stein MB, Sieber WJ. Gender differences in long-term posttraumatic stress disorder outcomes after major trauma: women are at higher risk of adverse outcomes than men. J Trauma. 2002;53(5):882-888. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200211000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trost Z, Agtarap S, Scott W, et al. Perceived injustice after traumatic injury: associations with pain, psychological distress, and quality of life outcomes 12 months after injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2015;60(3):213-221. doi: 10.1037/rep0000043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Stein MB, Sieber WJ. Perceived threat to life predicts posttraumatic stress disorder after major trauma: risk factors and functional outcome. J Trauma. 2001;51(2):287-292. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Diagram Detailing Study Population

eTable. Comparison of Demographic, Clinical, and PROMIS Metrics Based on ICU Admission