Key Points

Question

Is brief cognitive behavioral therapy cost-effective vs treatment as usual for preventing suicidal behaviors among at-risk US Army soldiers?

Findings

In this economic evaluation, data from a published clinical trial and multiple epidemiologic data sets were used to estimate that brief cognitive behavioral therapy may be cost saving compared with treatment as usual. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy remained cost-effective in sensitivity analyses that explored alternative scenarios.

Meaning

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy appears to be a cost-effective intervention for at-risk soldiers and should be considered for widespread implementation.

Abstract

Importance

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy (BCBT) is a clinically effective intervention for reducing risk of suicide attempts among suicidal US Army soldiers. However, because specialized treatments can be resource intensive, more information is needed on costs and benefits of BCBT compared with existing treatments.

Objective

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of BCBT compared with treatment as usual for suicidal soldiers in the US Army.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A decision analytic model compared effects and costs of BCBT vs treatment as usual from a US Department of Defense (DoD) perspective. Model input data were drawn from epidemiologic data sets and a clinical trial among suicidal soldiers conducted from January 31, 2011, to April 3, 2014. Data were analyzed from July 3, 2018, to March 25, 2019.

Interventions

The strategies compared were treatment as usual alone vs treatment as usual plus 12 individual BCBT sessions. Treatment as usual could include a range of pharmacologic and psychological treatment options.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Costs in 2017 US dollars, suicide attempts averted (self-directed behavior with intent to die, but with nonfatal outcome), suicide deaths averted, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, assuming a 2-year time horizon for treatment differences but including lifetime costs.

Results

In the base-case analysis, BCBT was expected to avert approximately 23 to 25 more suicide attempts and 1 to 3 more suicide deaths per 100 patients treated than treatment as usual. Sensitivity analyses assuming a range of treatment effects showed BCBT to be cost saving in most scenarios. Using the federal discount rate, the DoD was estimated to save from $15 000 to $16 630 per patient with BCBT vs treatment as usual. In a worst-case scenario (ie, assuming the weakest plausible BCBT effect sizes), BCBT cost an additional $1910 to $2250 per patient compared with treatment as usual.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results suggest BCBT may be a cost-saving intervention for suicidal active-duty soldiers. The costs of ensuring treatment fidelity would also need to be considered when assessing the implications of disseminating BCBT across the entire DoD.

This economic evaluation compares the use of brief cognitive behavioral therapy with the usual treatment given in suicidal US Army soldiers.

Introduction

In response to increasing suicides in the US military,1,2 the US Department of Defense (DoD) has prioritized suicide prevention,3 implementing many different preventive interventions. The cost-effectiveness of these interventions has not been systematically assessed; in most cases, the comparative efficacy of the interventions used in military service members remains unknown.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is currently the psychological treatment with the most consistent meta-analytic evidence for reducing suicide attempts.4,5 Cognitive behavioral therapy is most effective when it targets suicidal thoughts or behaviors directly as opposed to targeting mental disorders or other risk factors.6 Brief CBT (BCBT) is one such suicide-focused CBT, and its brevity and flexibility enable it to accommodate the unpredictable demands of military service. Over 12 sessions, the clinician and patient analyze precipitants of the crisis, create and practice a crisis response plan, practice emotion regulation skills, and reduce cognitions associated with suicidal behavior (eg, hopelessness). A trial that randomized 152 Army soldiers presenting with recent suicidal crises (attempt or ideation with intent to die) to receive treatment as usual or BCBT plus treatment as usual found that adding BCBT significantly reduced soldiers’ likelihood of future suicide attempts,7 which was an effect not attributable to receiving a higher psychotherapy dose.8

Despite this evidence, it remains unclear whether BCBT should be considered a standard treatment for service members after a suicidal crisis, because the most effective treatment might not be the most cost-effective treatment. New treatments typically cost more than the current standard of care, including new psychological treatments, which can be resource intensive to disseminate because of training and quality-control monitoring costs.9 Cost-effectiveness analysis assesses whether such treatments produce enough health gains to justify their costs or whether implementing the intervention could draw resources away from other treatments that produce more health per dollar spent. Cost-effectiveness modeling can also incorporate sensitivity analysis to address uncertainty in estimates of effect sizes. The magnitude of BCBT’s effect among service members remains unclear because, to our knowledge, only 1 trial among soldiers has been published, although suicide-focused CBT has consistently shown benefits among civilians4,5; sensitivity analysis can reveal whether BCBT would remain cost-effective at different effect sizes.

To assist DoD decision makers, we estimated the cost-effectiveness from the DoD perspective of providing BCBT to US Army soldiers with a recent suicidal crisis. To be clear, the aim of cost-effectiveness analysis is not to save money at the expense of lives, but rather to identify treatment strategies that optimally allocate resources to maximize health gains.

Methods

Model Overview and Inputs

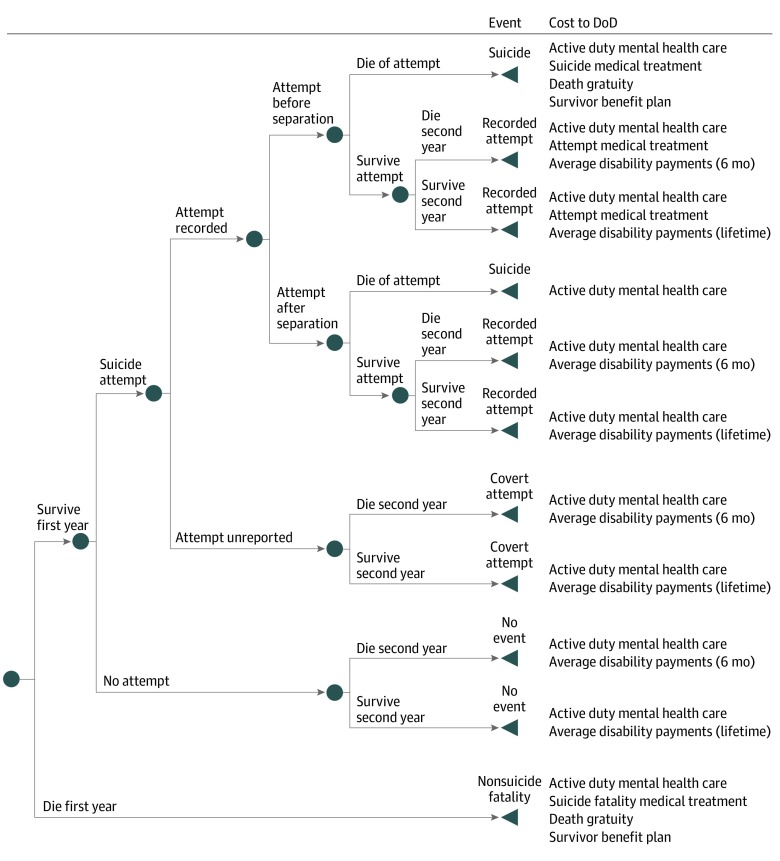

We developed a decision-analytic model (Figure 1) to compare costs, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths among patients treated with BCBT vs treatment as usual for the target population of Army soldiers presenting with a recent suicidal crisis. In this model, the probability of each event was multiplied by the event’s cost to compute total costs for each of the 2 treatments. The model assumes that all treatment effects end after 2 years. Because this duration corresponds to the follow-up length of the trial providing data, the effects of psychological treatment beyond 2 years remain understudied,10 and treatment differences typically decay.11

Figure 1. Decision Tree Structure for Each Strategy.

Terminal nodes are labeled with the event and with costs that would be paid by the Department of Defense (DoD).

We included direct costs from the DoD perspective in 2017 US dollars: medical costs and compensation provided to disabled retirees and decedents’ next of kin. Consistent with the DoD perspective, we only included health care costs accrued before separation from duty, and we included lifetime costs of disability and next-of-kin benefits. However, the DoD may have a goal of reducing suicide attempts and deaths regardless of when they occur despite the lack of direct consequences on the DoD budget. To capture the investment required from the DoD to avert these negative events for the benefit of society, we also present the incremental cost to the DoD per event averted, regardless of event timing. In other words, this cost includes what the DoD would need to pay to prevent a suicide attempt or death before or after a soldier separates from service. Input values for the base case and sensitivity analyses7,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 appear in Table 1. Model input data were drawn from epidemiologic data sets and a clinical trial among suicidal soldiers conducted from January 31, 2011, to April 3, 2014. Data were analyzed from July 3, 2018, to March 25, 2019. This study followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) reporting guideline.23 Deidentified data were provided to 2 of us (S.L.B. and K.L.Z.) via a data-sharing agreement between the National Center for Veterans Studies at the University of Utah and Harvard University. The original trial's procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Madigan Army Medical Center. The need for further study approval was waived by the institutional review boards of the University of Utah and Harvard University.

Table 1. Model Input Data.

| Parameter | Base Case | Sensitivity Analysis Value or Distributiona | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| General input | |||

| Annual discount rate, % | Federal rate | 3% | Sanders et al12; US Office of Management and Budget13 |

| Time horizon | Lifetime for costs/benefits, 2 y for treatment effects | NA | NA |

| Event probabilities | |||

| Suicide attempt probability, % | Rudd et al7 | ||

| Treatment as usual | 39.5 | 37.1 For weaker and lower-bound scenarios | |

| BCBT | 13.5 | 22.5 For weaker and 31.8 for lower-bound scenarios | |

| Attempt medical/administrative record probability, % | 64.5 | β (α = 40, β = 21) | Rudd et al7 |

| Death probability/recorded attempt, % | Army STARRS,b CDC WISQARS14 | ||

| Higher lethality (Army) | 17.2 | β (α = 279, β = 1340) | |

| Lower lethality (civilian) | 7.1 | β (α = 44 000, β = 575 000) | |

| Attempt before separation probability/attempt, % | 61.1 | β (α = 11, β = 7) | Rudd et al7 |

| Disability evaluation probability, % | Rudd et al7 | ||

| Treatment as usual | 57.6 | β (α = 38, β = 28) | |

| BCBT | 39.4 | Treatment as usual probability × e normal, mean (SD): 0.378 (0.181) | |

| Disability rating probability/disability evaluation, % | 90.0 | β (α = 45, β = 5) | Rudd et al7 |

| Background mortality probability, % | DoD OACT15; NCVAS16 | ||

| Year 1 treatment as usual and BCBT | 0.069 | NA | |

| Year 2 treatment as usual | 0.185 | Varied based on proportion disabled | |

| BCBT | 0.168 | Varied based on proportion disabled | |

| Event timing | |||

| Time to attempt, d | Rudd et al7 | ||

| Treatment as usual | 279 | 245 For weaker and lower-bound scenarios | |

| BCBT | 152 | 295 For weaker and 245 for lower-bound scenario | |

| Time to, d | |||

| Separation | 348 | NA | Rudd et al7 |

| Death from other causes | NA | ||

| Year 1 | 183 | NA | |

| Year 2 | 548 | NA | |

| Surviving spouse life expectancy, y | Arias et al17 | ||

| Male patients’ wives | 57 | NA | |

| Female patients’ husbands | 50.7 | NA | |

| Child coverage expectancy, y | 17.5 | NA | DoD OACT15 |

| Disabled retiree life expectancy, y | 48 | NA | DoD OACT15 |

| Treatment costs | |||

| Mental health care total costs, 2017 US $ | Rudd et al7; MHS M2b | ||

| Treatment as usual | 20 244 | Normal, mean (SD): 20 244 (2780) | |

| BCBT | 15 832 | Treatment as usual cost + normal, mean (SD): −4413 (3894) | |

| Suicide medical cost, 2017 US $c | |||

| Suicide death | 5031 | NA | CDC WISQARS14 |

| Suicide attempt | 3043 | NA | MHS M2b |

| Other death | 30 000 | NA | eAppendix in the Supplement |

| Benefit costs | |||

| Annual retired disability pay, 2017 US $ | 1282 | Normal, mean (SD): 1284 (353) | Defense Finance and Accounting Service18 |

| Annual survivor benefit annuity, 2017 US $ | |||

| Spouse beneficiary | 3720 | NA | 10 USC §§ 1447-1460B19; 38 USC §§ 1301-132220; 38 CFR §§ 321 |

| Child beneficiary | 12 322 | NA | 10 USC §§ 1447-1460B19; 38 USC §§ 1301-132220; 38 CFR §§ 321 |

| Death gratuity | 100 000 | NA | 20 CFR § 10, Subpart J22 |

Abbreviations: Army STARRS, Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers; BCBT, Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CDC WISQARS, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System; CFR, Code of Federal Regulations; DoD OACT, Department of Defense Office of the Actuary; MHS M2, Military Health System Management Analysis and Reporting Tool data sets; NA, not applicable; NCVAS, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; USC, United States Code.

Where appropriate, SEs of continuous values estimated from the data appear in this column as the SDs used to generate normally distributed values for probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Original analysis of unpublished data.

Medical cost refers to medical care other than mental health care.

Demographic Data and Background Mortality

Demographic data on the target population (ie, soldiers with recent suicidal crises) were drawn from 2 sources: the BCBT trial that randomized 152 Army soldiers7 and the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS), a multicomponent, epidemiologic-neurobiologic study of US Army soldiers.24 Two STARRS components contributed data: the All-Army Survey, a large representative survey of Army soldiers, and the Historical Administrative Data System, a compilation of administrative records. Suicide attempter demographic information from the All-Army Survey corresponded well to BCBT trial participant demographics, suggesting that trial participants were reasonably representative of soldiers at risk for suicide attempt.

To account for background mortality, we estimated mortality probability in the first or second year after receiving treatment for a cohort of soldiers with the same age distribution as the target population. For deaths in year 1, we used active-duty mortality rates15 because the median time to separation was the end of the first year, and for deaths in year 2, we used a weighted combination of veteran16 and disabled retiree mortality rates.15

Treatment Effects

Data on treatment effects were drawn from the BCBT trial that randomized active-duty soldiers with past-month suicide attempt or past-week ideation with intent to die to treatment as usual or treatment as usual plus 12 individual outpatient BCBT sessions.7 Treatment as usual could include medication; individual or group psychotherapy; and intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, and/or inpatient treatment. Data were collected for 2 years on suicide attempts, use of mental health care services, and separation from the Army. We had access to raw trial data and therefore report results not presented in the original publication. Based on trial results, our model assumed the existence of advantages of BCBT over treatment as usual alone on the probability of suicide attempts, probability of disability retirement, and mental health care visit counts, including the BCBT visits in the intervention. Because of the uncertainty conferred by relying on 1 trial, we tested alternative effect sizes in sensitivity analyses.

Other Probabilities and Event Times

We also used trial data to estimate values that were assumed to be the same regardless of assignment based on finding no significant or appreciable differences in the trial: probability of suicide attempt being administratively recorded vs only self-reported, time to Army separation, and proportion of suicide attempts before vs after separating.

Probability of Dying by Suicide

The trial was powered to detect differences in likelihood of suicide attempt, but not death, owing to the lower base rate of the latter. Therefore, to simulate treatment effects on suicide deaths, we assumed that a proportion of medically and/or administratively recorded2 suicide attempts would result in death—in other words, that they would actually be suicides. We applied a probability of death only to medically and/or administratively recorded suicide attempts in the model because the ratios available in the literature represent the proportion of medically and/or administratively recorded suicide attempts that are fatal and omit covert/unreported suicide attempts in the denominator. More than one-third of attempts during follow-up were reported only in clinical interviews and not medically or administratively recorded. Historical Administrative Data System 2004-2014 data suggested that approximately 17% of administratively recorded Army soldier suicide attempts ended in death. Based on this percentage, we assumed that for every 100 suicidal acts averted, 17 would be suicide deaths and the remaining 83 would be attempts. This proportion is higher than the proportions reported in civilian studies,25 implying either that a higher proportion of Army than civilian suicide attempts are underreported or that soldiers’ suicidal behaviors are more lethal than those of civilians. Because both explanations seemed plausible, we computed results with 2 lethality rates: the Historical Administrative Data System lethality rate and a rate drawn from US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System14 2010-2016 data on civilian suicides and self-harm hospital visits.

Costs

Mortality Costs

For suicide and nonsuicide deaths, we added costs of death gratuity, survivor benefit plan, and medical (ie, non–mental health) treatment. The death gratuity is a $100 000 lump sum paid to next-of-kin after any active-duty service member’s death.26 The survivor benefit plan consists of an annuity paid to spouse or children for certain active-duty deaths. The determination of beneficiary and annuity amount is complex and depends on the soldier's pay, whether the death was in the line of duty, next-of-kin demographics, and whether the soldier was retirement eligible.19,20,21 We computed the expected lifetime annuity per decedent separately for suicide and other deaths because line-of-duty determination and next-of-kin demographics were assumed to differ.

The mean medical treatment cost for Army soldiers who die by suicide was not available, so we used the cost for civilian men aged 18 to 45 years from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System database (2010 data), likely an underestimate because health care costs are higher in the DoD than in civilian health care systems,27 resulting in a more conservative analysis (ie, less favorable to BCBT). We estimated nonsuicide death medical treatment costs by obtaining costs from the civilian literature for the most common causes of death in the Army and weighting them by the percentage of deaths in each category,28 ignoring combat deaths because suicidal soldiers would likely be considered nondeployable. We expected costs of nonsuicide deaths to have little association with the results owing to their infrequency over the time horizon.

Suicide Attempt Cost

For nonfatal suicide attempts, the only cost applied was the medical treatment cost (excluding mental health because this was included separately in the model) for the proportion of suicide attempts before separation that were medically and/or administratively recorded. Cost data from 2017 were obtained for all active-duty Army soldiers in the continental United States from the Military Health System Management Analysis and Reporting Tool (M2) data sets.

Mental Health Treatment Costs

Trial data (patient report supplemented with administrative records) were used to estimate quantities of individual psychotherapy sessions, group psychotherapy sessions (including partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient), psychiatric inpatient days, and intake evaluations for patients assigned to both treatment arms. The number of BCBT sessions is included in individual psychotherapy sessions. Unit costs were drawn from the 2017 M2 data sets.

The total mental health treatment cost for each trial patient was computed by multiplying units by costs per unit. We then conducted a regression analysis, with multiple imputation to address missingness, computing the pooled mean and SE for each treatment and estimated difference between the 2 treatments and the multiple imputation–based SEs of these estimated treatment effects.

Retired Disability Pay Costs

Calculating the DoD’s portion of retired disability pay requires information on base pay, military and Department of Veterans Affairs disability percentages, and demographics. Information was not formally gathered in the trial on military and Department of Veterans Affairs disability percentages, but nevertheless, both were recorded for approximately 80% of during-trial disability retirements. We calculated disability pay for individuals using publicly available online calculators,18,29 then used multiple imputation to account for missing data when estimating the mean and SE. Lifetime disability pay for each condition was computed by multiplying the probability that a soldier would retire owing to disability by annual disability pay by disabled veteran life expectancy.

Discounting and Inflation

The US government mandates use of its own discount rates in cost-effectiveness analyses13 based on interest rates and inflation forecasts. The current rates begin at −0.8% and increase over time. Per the recommendations of the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine,12 and for comparability with other health care cost-effectiveness analyses,30 we also present results using a 3% discount rate. Health care costs from pre-2017 sources were inflated to 2017 dollars using the consumer price index25 medical care component, the standard index for inflating medical costs in DoD cost analyses.31

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using R statistical software, version 3.5 (R Foundation). We conducted analyses under 3 scenarios representing different possible effect sizes of BCBT on suicide attempts and, through attempts, on suicide deaths: (1) the base case, generated from trial data survival analysis; (2) a scenario assuming a weaker treatment effect by attenuating the hazard ratio by 1 SE; and (3) a scenario assuming a lower-bound treatment effect by attenuating the hazard ratio by 1.96 SEs (ie, the lower bound of the 95% CI). We also created a worst-case scenario in which we fixed BCBT’s effects on mental health care costs and the likelihood of receiving disability pay to the most unfavorable end of each 95% CI. We ran all analyses separately using the high-lethality (Army) and lower-lethality (civilian) probabilities of dying from a suicide attempt. Under the high-lethality scenario, a larger proportion of the suicidal behaviors averted are counted as suicides rather than attempts.

In addition, we conducted probabilistic sensitivity analysis that varied multiple uncertain parameters simultaneously. Table 1 lists parameter distributions for the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, which were for the most part derived directly from available data. For each of 10 000 simulations, each parameter’s value was randomly drawn from its distribution. When a parameter differed between treatments, we allowed the value to vary for treatment as usual and drew from a distribution of the difference between treatment as usual and BCBT to calculate the parameter for BCBT.

Results

Estimates of BCBT’s cost per patient treated, number of suicide attempts and deaths averted per patient treated, and costs per outcome under each scenario are reported in Table 2. All values are incremental relative to treatment as usual. In all but the worst-case scenario, BCBT was projected to be cost saving relative to treatment as usual. Estimated savings were greater when using the federal discount rate ($15 000-$16 630) because future costs averted (ie, disability and survivor benefit plan payments) were discounted less. In the worst-case scenario, BCBT cost the DoD an additional $1910 to $2250 per patient than treatment as usual. In the base case, we estimated that BCBT would avert approximately 23 more attempts and 3 more suicide deaths than treatment as usual per 100 patients treated in the high-attempt lethality scenario compared with 25 attempts and 1 suicide death in the lower-lethality scenario.

Table 2. Estimated Costs and Effect Sizes of BCBT vs Treatment as Usuala.

| Scenario | Incremental Cost of BCBT vs Treatment as Usual | ICER, $/Suicide Attempt Averted | ICER, $/Suicide Death Averted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Discount Rate | 3% Discount Rate | Attempts Averted | Suicides Averted | Federal Discount Rate | 3% Discount Rate | Federal Discount Rate | 3% Discount Rate | |

| Base Case | ||||||||

| High lethalityb | −16 630 | −11 920 | 0.231 | 0.029 | −72 110 | −51 680 | −576 500 | −413 190 |

| Low lethalityc | −15 000 | −10 480 | 0.248 | 0.012 | −60 570 | −42 340 | −1 260 110 | −880 990 |

| Weaker Effect Size | ||||||||

| High lethality | −15 120 | −10 630 | 0.129 | 0.016 | −116 900 | −82 190 | −934 570 | −657 080 |

| Low lethality | −14 290 | −9870 | 0.139 | 0.007 | −102 930 | −71 100 | −2 141 530 | −1 479 210 |

| Lower-Bound Effect Size | ||||||||

| High lethality | −13 870 | −9570 | 0.047 | 0.006 | −294 880 | −203 480 | −2 357 370 | −1 626 730 |

| Low lethality | −13 710 | −9370 | 0.051 | 0.002 | −271 500 | −185 530 | −5 648 760 | −3 860 110 |

| Worst-Case Scenario | ||||||||

| High lethality | 1910 | 2310 | 0.047 | 0.006 | 40 650 | 49 010 | 325 000 | 391 820 |

| Low lethality | 2250 | 2600 | 0.051 | 0.002 | 44 530 | 51 480 | 926 470 | 1 071 170 |

Abbreviations: BCBT, Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

All costs and effects are per patient treated.

Costs and effect sizes assuming higher lethality of suicide attempts based on Army data.

Costs and effect sizes assuming lower lethality of suicide attempts based on civilian data.

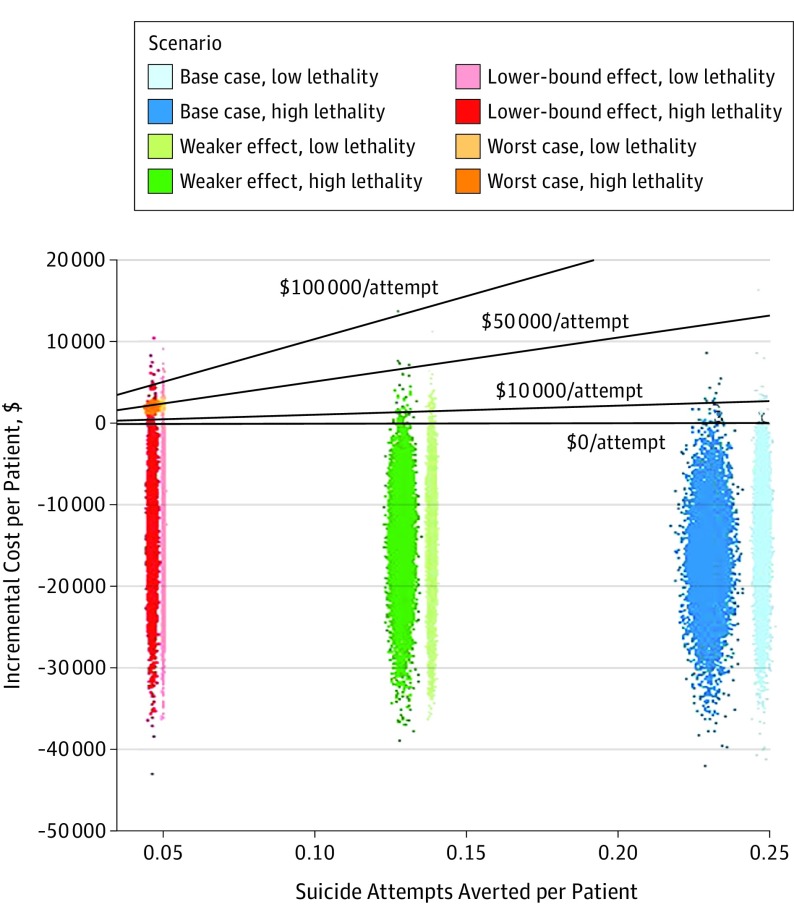

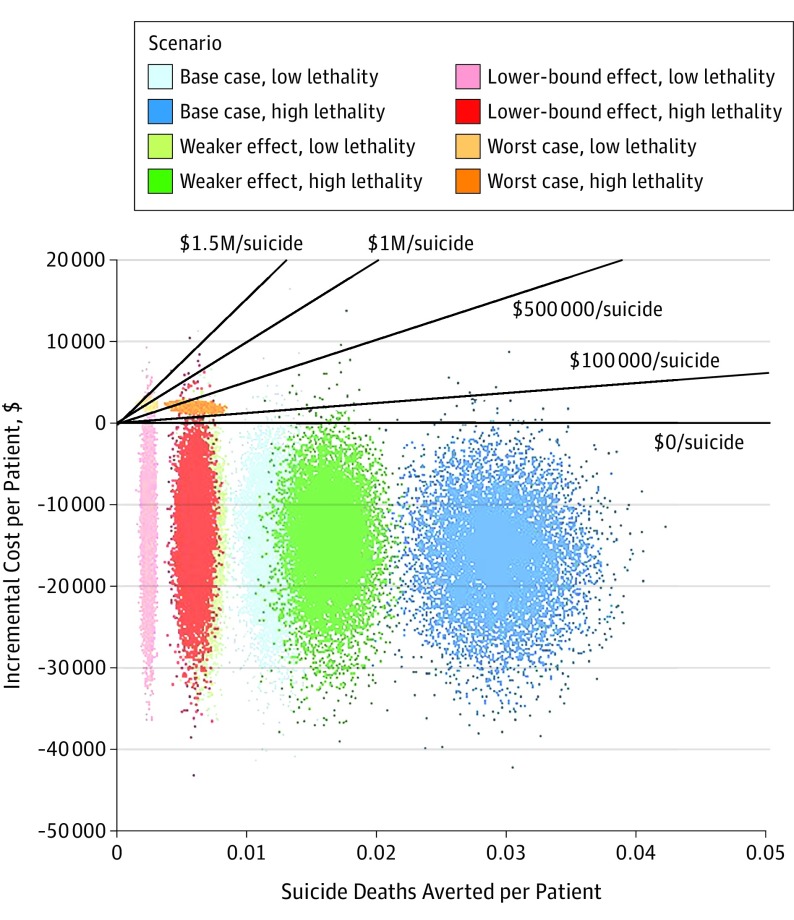

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results for the federal discount rate appear in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Each point represents the results of 1 of the 10 000 simulations for each scenario, with the incremental cost of BCBT plotted against the number of events averted per patient treated. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results for the 3% discount rate appear in eFigure 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement. To our knowledge, no official cost-effectiveness threshold exists for this perspective and these outcomes, so we plot lines for various thresholds. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy remained cost saving in most simulations.

Figure 2. Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis Results for Suicide Attempt Averted.

Incremental cost of brief cognitive behavioral therapy relative to treatment as usual per suicide attempt averted, federal discount rate.

Figure 3. Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis Results for Suicide Death Averted .

Incremental cost of brief cognitive behavioral therapy relative to treatment as usual per suicide death averted, federal discount rate.

Discussion

We found BCBT to be cost saving and to be associated with reduced adverse outcomes compared with treatment as usual in nearly all scenarios, including in sensitivity analyses that assumed BCBT to be less clinically effective. Even under our worst-case scenario, BCBT’s incremental cost per suicide attempt and death averted falls well below reasonable thresholds (eg, the value of a statistical life, approximately $9 million).32 We suggest that BCBT is a cost-effective intervention for active-duty soldiers with recent suicidal crises. Only a small proportion of suicides in the Army are attributable to the narrow subset of soldiers who present in crisis. There is no indication that BCBT would be cost-effective for all service members reporting suicidal ideation. Disseminating BCBT throughout the DoD would incur additional costs of training and quality-control monitoring,33 but even high training costs may be outweighed by the cost savings in many scenarios, leaving BCBT cost saving overall. For example, a $2000 course and 40 hours of consultation at $100/h per clinician would amount to $6000. If the clinician treated as few as 3 patients with BCBT, the per-patient cost would fall to $2000, which would be more than offset by the base-case cost savings.

These results are notable because most interventions incur increased costs to achieve health gains. However, evidence suggests that mental health care is a particularly good investment. Several reviews have found positive returns for some psychological treatments when accounting for factors such as medical cost offset and increased labor productivity.34,35,36,37 Our analysis joins other recent work38 in highlighting the utility of economic evaluations when considering expanding suicide-focused interventions. Given that few suicide prevention randomized clinical trials exist,5 including economic evaluations alongside trial results might accelerate dissemination and implementation efforts.

Limitations

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. There was uncertainty in parameter estimates: only 1 clinical trial served as the basis for most treatment effect estimates; we did not have adequate information to model associations between most parameters, requiring us to assume independence; and considerable uncertainty remains regarding the probability of death from a suicide attempt. We generally made conservative analytic choices to address these uncertainties, such as assuming that BCBT’s effects would not endure beyond 2 years. As another conservative choice, we limited our analysis to direct costs. However, providing BCBT would also reduce indirect costs through productivity changes. For example, service members’ productivity may increase; in addition, suicides require numerous investigations, and averting deaths would free the individuals conducting investigations for other productive work. Consequently, this analysis represents a lower bound estimate of BCBT’s benefit to the DoD. We also lacked information on use of psychiatric medications. Our DoD perspective and focus on the Army limits our findings’ generalizability. We took a DoD perspective to inform DoD decision makers and consequently did not consider costs and benefits to the Department of Veterans Affairs or society. We also used treatment effect estimates, costs, policies, and demographics from the Army, and these parameters may differ slightly for other military branches. In addition, some costs included in this analysis would not apply in nonmilitary settings. Given BCBT’s possibly positive effects on suicidal behavior and use of mental health care, further studies should investigate whether BCBT would be a cost-effective treatment for civilians.

Conclusions

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy is likely cost saving relative to treatment as usual in addition to being more effective, and therefore represents an opportunity for the DoD to invest in human capital. If the DoD disseminates BCBT for service members with recent suicidal crises, it will be critical to work with dissemination and implementation experts to ensure treatment fidelity through effective and efficient training. To bolster confidence in BCBT’s effectiveness, the DoD can await results of an ongoing trial,39 but sensitivity analyses suggest that BCBT will remain cost saving even if its effects are weaker than predicted.

eAppendix. Calculation of Average Lifetime Survivor Benefit Plan Annuity, Non-Suicide Death Medical Cost, Suicide Attempt Medical Cost, and Mental Health Treatment Costs

eReferences

eFigure 1. Incremental Cost of BCBT Relative to TAU per Suicide Attempt Averted, 3% Discount Rate

eFigure 2. Incremental Cost of BCBT Relative to TAU per Suicide Death Averted, 3% Discount Rate

References

- 1.Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Reger MA, Bush NE, Skopp NA, Campise RL; National Center for Telehealth and Technology (T2) Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) Calendar Year 2016. https://www.dspo.mil/Portals/113/Documents/DoDSER%20CY%202016%20Annual%20Report_For%20Public%20Release.pdf?ver=2018-07-02-104254-717. Published June 2017. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 2.US Dept of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Veteran suicide data report, 2005-2016. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide_Data_Report_2005-2016_508.pdf. Published September 2018. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 3.US Department of Defense Department of Defense Strategy for Suicide Prevention. https://www.dspo.mil/Portals/113/Documents/TAB%20B%20-%20DSSP_FINAL%20USD%20PR%20SIGNED.PDF. Published December 2015. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 4.Gøtzsche PC, Gøtzsche PK. Cognitive behavioural therapy halves the risk of repeated suicide attempts: systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2017;110(10):404-410. doi: 10.1177/0141076817731904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, et al. Psychosocial interventions for self-harm in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD012189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meerwijk EL, Parekh A, Oquendo MA, Allen IE, Franck LS, Lee KA. Direct versus indirect psychosocial and behavioural interventions to prevent suicide and suicide attempts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(6):544-554. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00064-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudd MD, Bryan CJ, Wertenberger EG, et al. Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(5):441-449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan CJ, Rudd MD. Response to Stankiewicz et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):1022-1023. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060774r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martino S, Paris M Jr, Añez L, et al. The effectiveness and cost of clinical supervision for motivational interviewing: a randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;68:11-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinert C, Hofmann M, Kruse J, Leichsenring F. Relapse rates after psychotherapy for depression—stable long-term effects? a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:107-118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conradi HJ, Bos EH, Kamphuis JH, de Jonge P. The ten-year course of depression in primary care and long-term effects of psychoeducation, psychiatric consultation and cognitive behavioral therapy. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:174-182. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093-1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Office of Management and Budget Guidelines and Discount Rates for Benefit-Cost Analysis of Federal Programs (Circular A-94). Washington, DC: US Dept of Transportation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Published February 19, 2017. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 15.Defense Human Resources Activity Office of the Actuary Valuation of the Military Retirement System September 30, 2016. Alexandria, VA: Dept of Defense; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics Mortality Rates and Life Expectancy of Veterans from 1980 to 2014, and by Education and Income. Washington, DC: Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arias E, Heron M, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2014. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retirement Disability Pay Estimator https://www.dfas.mil/militarymembers/woundedwarrior/disabledretireest.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- 19.Survivor Benefit Plan. 10 USC §§1447-1460B (2011).

- 20.Dependency and Indemnity Compensation. 38 USC §§1301-1322 (2011).

- 21.Adjudication. 38 CFR §§3 (2003).

- 22.US Department of Labor. Claims for compensation under the federal employees' compensation act, as amended: death gratuity. 20 CFR § 10, Subpart J.

- 23.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. ; ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines-CHEERS Good Reporting Practices Task Force . Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)—explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):231-250. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB; Army STARRS Collaborators . The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 2014;77(2):107-119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Medical Care [CPIMEDSL]. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIMEDSL. Accessed February 16, 2019.

- 26.House Committee on Armed Services. Death benefits. 10 USC § 1475.

- 27.Lurie P. Comparing the costs of Military Treatment Facilities With Private Sector Care. Alexandria, VA: Institute for Defense Analyses; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mancha B, Abdur-Rahman I, Mitchell T, et al. Mortality Surveillance in the US Army 2005-2014. Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD: Army Public Health Center; 2016:0034370-14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regular Military Compensation (RMC) Calculator https://militarypay.defense.gov/calculators/rmc-calculator/. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- 30.Cangelosi MJ. Health economic implications and consumer preference distortions of negative interest rate policy. Paper presented at: 22nd annual meeting of ISPOR, The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research; May 2017; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wise G, Lochbryn C, Oprisu D. Department of Defense Inflation Handbook. 2nd ed McLean, VA: MCR Federal, LLC, for Office of the Secretary of Defense, Cost Analysis and Program Evaluation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson LA, Hammitt JK. Research synthesis and the value per statistical life. Risk Anal. 2015;35(6):1086-1100. doi: 10.1111/risa.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(4):448-466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiles JA, Lambert MJ, Hatch AL. The Impact of Psychological Interventions on Medical Cost Offset: A Meta-analytic Review. Vol 6 Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 1999:204-220. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuhldreher N, Konnopka A, Wild B, et al. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in eating disorders: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(4):476-491. doi: 10.1002/eat.20977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konnopka A, Leichsenring F, Leibing E, König HH. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in anxiety disorders: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):14-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(5):415-424. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park AL, Gysin-Maillart A, Müller TJ, Exadaktylos A, Michel K. Cost-effectiveness of a brief structured intervention program aimed at preventing repeat suicide attempts among those who previously attempted suicide: a secondary analysis of the ASSIP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183680. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryan C. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy replication trial. 2018; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03769259?recrs=abdf&outc=suicide+attempt&draw=2. Accessed November 6, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Calculation of Average Lifetime Survivor Benefit Plan Annuity, Non-Suicide Death Medical Cost, Suicide Attempt Medical Cost, and Mental Health Treatment Costs

eReferences

eFigure 1. Incremental Cost of BCBT Relative to TAU per Suicide Attempt Averted, 3% Discount Rate

eFigure 2. Incremental Cost of BCBT Relative to TAU per Suicide Death Averted, 3% Discount Rate