Key Points

Question

Does marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation reduce risk of colorectal cancer precursors in the US general population?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 25 871 adults, daily supplementation of marine ω-3 fatty acid, 1 g, did not reduce risk of conventional adenomas or serrated polyps. A suggestive beneficial association was observed among individuals with low plasma levels of ω-3 fatty acid at baseline and among African American persons.

Meaning

Daily supplementation with marine ω-3 fatty acids, 1 g, appears not to reduce the risk of colorectal premalignant lesions in the average-risk US population; however, individuals with low plasma levels of ω-3 or African American persons may benefit.

Abstract

Importance

Marine ω-3 fatty acid has been suggested to protect against colorectal cancer.

Objective

To assess the effect of daily marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation on the risk of colorectal cancer precursors, including conventional adenomas and serrated polyps.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was a prespecified ancillary study of the placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial VITAL (Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial). An intention-to-treat analysis was used to examine the effect of daily marine ω-3 supplements among 25 871 adults in the US general population (including 5106 African American persons) free of cancer and cardiovascular disease at enrollment. Randomization was from November 2011 to March 2014, and intervention ended as planned on December 31, 2017.

Interventions

Marine ω-3 fatty acid, 1 g daily (which included eicosapentaenoic acid, 460 mg, and docosahexaenoic acid, 380 mg) and vitamin D3 (2000 IU daily) supplements.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Risk of conventional adenomas (including tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, villous adenoma, and adenoma with high-grade dysplasia) or serrated polyps (including hyperplastic polyp, traditional serrated adenoma, and sessile serrated polyp). In a subset of participants who reported receiving a diagnosis of polyp on follow-up questionnaires, endoscopic and pathologic records were obtained to confirm the diagnosis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated using logistic regression, after adjusting for age, sex, vitamin D treatment assignment, and use of endoscopy. Secondary analyses were performed according to polyp features and participants’ characteristics.

Results

The demographic characteristics of participants at randomization were well balanced between the treatment and placebo groups; for example, 50.6% vs 50.5% were women, and 19.7% vs 19.8% were African American persons were included in each group. The mean (SD) age was 67.1 (7.1) years in the placebo group and 67.2 (7.1) in the ω-3 treatment group. During a median follow-up of 5.3 years (range, 3.8-6.1 years), 294 cases of conventional adenomas were documented in the ω-3 group and 301 in the control group (multivariable OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.83-1.15) (1:1 ratio between number of cases and number of participants). In addition, 174 cases of serrated polyps were documented in the ω-3 group and 167 in the control group (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.29). Null associations were found for polyp subgroups according to size, location, multiplicity, or histology. In secondary analyses, marine ω-3 treatment appeared to be associated with lower risk of conventional adenomas among individuals with low plasma levels of ω-3 index at baseline (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.57-1.02; P = .03 for interaction by ω-3 index). A beneficial association of supplementation was also noted in the African American population (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.35-1.00) but not in other racial/ethnic groups (P = .11 for interaction).

Conclusions and Relevance

Supplementation with marine ω-3 fatty acids, 1 g per day, was not associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer precursors. A potential benefit of this supplementation for individuals with low baseline ω-3 levels or for African American persons requires further confirmation.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01169259

This prespecified ancillary study of a randomized clinical trial compares the effects of daily marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation vs placebo on risk of colorectal cancer precursors, including conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, in an average-risk US population.

Introduction

Marine ω-3 fatty acids are a group of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids that include eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid and are rich in marine food sources. Experimental data indicate that marine ω-3 fatty acids have potent anti-inflammatory effects and may protect against colorectal cancer (CRC),1 the fourth most common cancer in the United States.2 Marine ω-3 fatty acids have been shown to block prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2–mediated production of inflammatory eicosanoids through competitive inhibition of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid. In vitro studies have shown that enrichment of ω-3 fatty acid in the plasma membrane alters the organization of membrane signaling assemblies that are associated with changes in multiple cellular processes in colonic tumorigenesis, including reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis.3

Although epidemiologic data remain inconclusive, several prospective studies have indicated that a putative chemopreventive benefit of marine ω-3 fatty acids may act in the early stage of CRC development.4,5 Colorectal cancer develops through a multistep process involving 2 major pathways that are characterized by distinct groups of premalignant lesions, including conventional adenomas and serrated polyps.6 Mixed findings have been reported in observational studies that have assessed the association of dietary intake or plasma levels of marine ω-3 fatty acids with risk of CRC precursors.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 In a randomized clinical trial, supplementation with EPA, 2 g daily for 6 months, has been shown to reduce the number and size of polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis.14 A recent phase 3 randomized clinical trial reported that EPA, 2 g per day, treatment decreases the number of colorectal adenomas detected per patient at 1-year surveillance colonoscopy among individuals with a history of adenoma removal.15 Despite these data, however, randomized clinical trial evidence in an average-risk population remains lacking.

Some members of our group recently reported the primary findings of a large-scale prevention trial, the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), that showed no reduction in the incidence of major cardiovascular events or cancer for ω-3 supplement administration although the number of cases was too small for a well-powered analysis on CRC risk.16 Therefore, to extend our knowledge about the effect of marine ω-3 fatty acid on CRC, we assessed the effect of ω-3 supplement administration on the risk of colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps, a prespecified ancillary outcome within VITAL.

Methods

Study Population

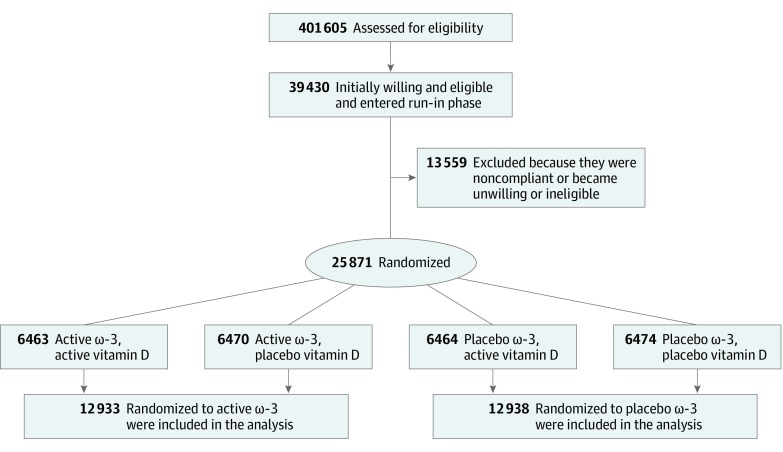

Details of the VITAL design and follow-up have been described previously.16,17,18 The study protocol is provided in Supplement 1. In brief, VITAL is a completed placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, with a 2-by-2 factorial design, that administered vitamin D3 (2000 IU per day) and marine ω-3 fatty acid (1 g per day as a fish-oil capsule containing marine ω-3 fatty acid, 840 mg, which included EPA, 460 mg, and DHA, 380 mg) to assess the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among 25 871 men 50 years or older and women 55 years or older residing in the United States (Figure). Details of the statistical power calculation for the primary and secondary end points have been described previously.18 The study had adequate power to detect risk reductions of 25% to 40% for secondary end points. The ω-3 dose was chosen based on the totality of prior evidence for both cardioprotective efficacy and safety as well as on the recommendation by the American Heart Association for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.19 The placebo capsule contained olive oil. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline for randomized clinical trials. The VITAL study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners Healthcare/Brigham and Women’s Hospital and was monitored by an external Data and Safety Monitoring Board. The study agents received Investigational New Drug Approval from the US Food and Drug Administration. All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure. Flow Diagram of VITAL (Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial).

Eligible participants had no history of cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer), myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or coronary revascularization at enrollment and were required to forgo the use of fish-oil supplements, to limit the use of vitamin D from all supplemental sources, including multivitamins, to 800 IU per day, and to complete a 3-month placebo run-in phase. Safety exclusions included renal failure or dialysis, cirrhosis, fish allergy, anticoagulant use, or other serious conditions that would preclude participation. Randomization took place from November 2011 to March 2014 and was computer generated within sex, race (African American vs not), and 5-year age groups in blocks of 8. Both study staff and participants were blinded to treatment assignment. Intervention ended as planned on December 31, 2017, yielding a median treatment period of 5.3 years (range, 3.8-6.1 years). The mean rate of adherence to the trial regimen reported by the participants (percentage taking at least two-thirds of the trial capsules) was 81.6% in the ω-3 group and 81.5% in the placebo group during 5 years of follow-up. Outside use was below 3.5% in each group throughout follow-up.16

Outcome Ascertainment

Annual questionnaires were administered to assess compliance, adverse effects, diagnoses of major illnesses, and risk-factor updates. On the fourth-year questionnaire, participants were asked whether they had received a diagnosis of any colorectal polyp in the past 4 years, and if yes, whether they had been asked by the physicians to return for a repeated colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy in 5 years or less. To confirm cases and identify high-risk cases in a cost-efficient manner (1:1 ratio between number of cases and number of participants), we acquired medical records only from participants who answered yes to both questions because they were more likely to have polyps than those who self-reported polyps alone. Similar questions and follow-up procedures were used in the fifth-year questionnaire. Details on polyp ascertainment are provided in the eFigure in Supplement 2.

Investigators blinded to any exposure information reviewed all records and extracted data on polyp size, number, and histologic subtype at each anatomic sublocation, including the proximal colon that encompasses the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, and splenic flexure; the distal colon that encompasses the descending or sigmoid colon; and the rectum that encompasses the rectum and rectosigmoid junction. We defined 2 case groups: conventional adenomas, which included tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, villous adenoma, and adenomas with high-grade dysplasia; and serrated polyps, which included hyperplastic polyp, traditional serrated adenoma, and sessile serrated adenoma with or without cytologic dysplasia. If a participant had both conventional adenoma and serrated polyp by endoscopy, the participant was counted in both case groups. We further classified cases into low- and high-risk subgroups on the basis of the size and histologic features of their polyps. For conventional adenomas, high-risk cases were defined as those having at least 1 conventional adenoma of 10 mm or greater in diameter or with advanced histology (tubulovillous or villous histology or high-grade dysplasia). For serrated polyps, high-risk cases were defined as those located in the proximal colon or with a size of 10 mm or greater.

Assessment of Covariates and Level of Plasma Marine ω-3 Fatty Acid

Participants completed a baseline questionnaire regarding their demographic, diet, clinical, and lifestyle risk factors, including family history of CRC, history of endoscopic examination, smoking status, body weight, height, alcohol consumption, physical activity, medication use, and use of dietary supplements. Blood samples were obtained at baseline from 15 535 willing participants and assayed for plasma EPA and DHA at Quest Diagnostics, using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. We calculated the plasma ω-3 index as the sum of the EPA and DHA levels, expressed as a percentage of total fatty acids.20

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated separately for the active treatment and placebo groups. We performed intention-to-treat analyses to examine the effect of treatment with ω-3 supplements. Logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for the risk of conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, comparing the ω-3 groups with the placebo groups. In line with a prior study,16 we adjusted for age, sex, and randomization group in the vitamin D portion of the trial (vitamin D or placebo group). We further adjusted for use of colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy in the 10 years prior to randomization. In addition to overall conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, we also performed subgroup analyses according to polyp features, including risk classification (low and high risk), size (<10 mm or ≥10 mm), sublocation (proximal colon, distal colon, or rectum), multiplicity (single or multiple), and histology (for conventional adenoma only: tubular, tubulovillous, villous, or high-grade dysplasia). We assessed the difference in the treatment effects across different polyp groups and calculated the P value for heterogeneity among cases only, with the case group classification as the dependent variable and treatment assignment as the independent variable. Finally, we performed stratified analyses according to several factors, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, regular aspirin use, baseline fish intake, plasma ω-3 index, history of colorectal polyps, history of colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy in the previous 10 years, and group assignment for the vitamin D treatment. We calculated the P value for interactions using the Wald test for the product terms between the stratified variable and ω-3 treatment assignment. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and 2-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 gives the basic characteristics of participants at randomization, which were generally well balanced between the treatment groups; for example, 50.6% vs 50.5% were women, and 19.7% vs 19.8% were African American persons. The mean (SD) age was 67.1 (7.1) years in the placebo group and 67.2 (7.1) in the ω-3 treatment group. Of 25 871 participants, 2852 reported on the questionnaires a diagnosis of colorectal polyps as of December 31, 2017, of whom we collected medical records from 999 participants (35.0%). Of these participants, we confirmed the diagnosis of conventional adenomas received by 294 individuals in the ω-3 group and 301 in the placebo group, and we confirmed the diagnosis of serrated polyps received by 174 individuals in the ω-3 group and 167 in the placebo group (eFigure in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants According to Marine ω-3 Fatty Acid Supplementationa.

| Variable | Participants, No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 12 938) | Marine ω-3 (n = 12 933) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 67.1 (7.1) | 67.2 (7.1) | .80 |

| Women | 6538 (50.5) | 6547 (50.6) | .89 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 9002 (69.6) | 9044 (69.9) | .75 |

| African American | 2557 (19.8) | 2549 (19.7) | |

| Others | 1092 (8.4) | 1060 (8.2) | |

| Missing | 287 (2.2) | 280 (2.2) | |

| Family history of colorectal cancerb | 1543 (11.9) | 1640 (12.7) | .08 |

| Colonoscopy in the past 10 y | 9423 (72.8) | 9492 (73.4) | .31 |

| Sigmoidoscopy in the past 10 y | 1622 (12.5) | 1577 (12.2) | .42 |

| Colonoscopy during the treatment period | 5046 (39.0) | 5116 (39.6) | .58 |

| Sigmoidoscopy during the treatment period | 458 (3.5) | 467 (3.6) | .86 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 6617 (51.1) | 6568 (50.8) | .85 |

| Past | 5213 (40.3) | 5251 (40.6) | |

| Current | 916 (7.1) | 920 (7.1) | |

| Missing | 192 (1.5) | 194 (1.5) | |

| BMI | 28.1 (5.8) | 28.1 (5.7) | .32 |

| Physical activity, MET-h/wk | 22.6 (25.5) | 22.8 (26.2) | .59 |

| Use of | |||

| Aspirin | 5799 (44.8) | 5771 (44.6) | .75 |

| Vitamin D supplementsc | 5532 (42.8) | 5498 (42.5) | .69 |

| Calcium supplementsd | 2616 (20.2) | 2550 (19.7) | .31 |

| Multivitamin supplements | 5745 (44.4) | 5661 (43.8) | .26 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Never | 4025 (31.1) | 3969 (30.7) | .67 |

| Rarely to less than once per week | 933 (7.2) | 976 (7.5) | |

| 1-6 per week | 4428 (34.2) | 4468 (34.5) | |

| Daily | 3323 (25.7) | 3315 (25.6) | |

| Missing | 229 (1.8) | 205 (1.7) | |

| Plasma fatty acid composition, mean (SD)e | |||

| EPA | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.4) | .95 |

| DHA | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) | .52 |

| ω-3 Indexf | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.9) | .52 |

| Dark meat fish intake, servings per week | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.9) | .80 |

| Other fish and seafood, servings per week | 1.1 (2.3) | 1.1 (2.4) | .95 |

| Processed meat, servings per week | 1.5 (2.4) | 1.5 (2.5) | .21 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; MET, metabolic equivalent.

Mean (SD) and percentages are presented for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Positive family history was defined as ever diagnosis of colorectal cancer among participants’ parents or siblings.

To be eligible for the trial, participants were required to limit consumption of supplemental vitamin D to no more than 800 IU per day from all supplemental sources combined.

To be eligible for the trial, participants were required to limit consumption of supplemental calcium to no more than 1200 mg per day from all supplemental sources combined.

Plasma data were available in 7782 participants in the control group (60%) and 7753 in the intervention group (60%) from those who provided a blood sample at enrollment.

Calculated as the sum of plasma EPA and DHA composition.

Marine ω-3 fatty acid treatment was not associated with risk of either conventional adenomas (multivariable OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.83-1.15) or serrated polyps (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.84-1.29) (Table 2). Similarly, no association was found for advanced adenomas or high-risk serrated polyps or other polyp subgroups according to size, location, multiplicity, or histology (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Because the participants were not screened uniformly for colorectal polyps before randomization, there is a possibility that some polyps diagnosed during the intervention period may have been prevalent at baseline. To address this, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding participants with colorectal polyps that occurred within the first 2 years after the start of the trial. Similar null results were found (for conventional adenomas: OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.79-1.13; for serrated polyps: OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.75-1.21). In another sensitivity analysis, we excluded individuals who did not report any lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy during follow-up. The results were essentially unchanged (for conventional adenomas: OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82-1.15; for serrated polyps: OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.87-1.36).

Table 2. Association of Marine ω-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation With Risk of Conventional Adenomas and Serrated Polypsa.

| Data | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Adenomas | Serrated Polyps | |||

| Placebo | Marine ω-3 | Placebo | Marine ω-3 | |

| Overall | ||||

| No. of cases | 301 | 294 | 167 | 174 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.83-1.15) | 1 [Reference] | 1.04 (0.84-1.29) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.83-1.15) | 1 [Reference] | 1.05 (0.84-1.29) |

| High riskd | ||||

| No. of cases | 67 | 74 | 84 | 95 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1.11 (0.79-1.54) | 1 [Reference] | 1.13 (0.84-1.52) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1.11 (0.80-1.55) | 1 [Reference] | 1.13 (0.84-1.52) |

| Low risk | ||||

| No. of cases | 234 | 220 | 83 | 79 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.78-1.13) | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.70-1.30) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.78-1.13) | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.70-1.30) |

There is a 1:1 ratio between number of cases and number of participants.

Logistic regression was adjusted for age, sex, and vitamin D treatment assignment.

Logistic regression was further adjusted for use of colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy in the 10 years prior to randomization.

For conventional adenoma, high-risk cases were defined as those having at least 1 conventional adenoma of 10 mm or greater in diameter or with advanced histology (tubulovillous or villous histologic features or high-grade dysplasia). For serrated polyp, high-risk cases were defined as those located in the proximal colon or with a size of 10 mm or greater.

In the secondary analyses (eTable 2 in Supplement 2), we found that ω-3 treatment was associated with lower risk of adenomas (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.35-1.00) in African American individuals, whereas no association was found in other racial/ethnic groups (for non-Hispanic white individuals: OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.89-1.28; for others: OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.48-1.52) (P = .11 for interaction). Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, African American persons had higher baseline intake of dark meat fish, the major food source of marine ω-3 fatty acid, higher plasma levels of DHA and ω-3 index, and slightly lower EPA levels (P < .001) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). When stratified by baseline plasma ω-3 index at the median level (2.5%), we also observed that ω-3 treatment was associated with lower risk of adenomas among individuals with an ω-3 index lower than 2.5% (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.57-1.02), whereas no association was found among those with an index of 2.5% or more (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.90-1.56) (P = .03 for interaction). The inverse associations for African American individuals and those with a low ω-3 index remained unchanged when we restricted analyses to participants who received a diagnosis at least 2 years after randomization. No interaction was detected according to subgroups defined by other demographic factors, CRC risk factors, history of endoscopy, baseline fish intake, or treatment assignment for vitamin D.

Discussion

In this large-scale prevention trial, supplementation with marine ω-3 fatty acid, 1 g per day, did not appear to affect the risk of conventional adenomas or serrated polyps compared with placebo. Secondary analyses indicated a potential benefit among African American persons or individuals with a low baseline ω-3 index. These findings provide novel data on the effect of marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation on the early stage of colorectal carcinogenesis and have implications for future studies.

Despite the experimental data suggesting a beneficial effect of marine ω-3 fatty acid on CRC, epidemiologic evidence remains inconclusive. A recent meta-analysis of 14 prospective studies on dietary intake of marine ω-3 fatty acid and CRC incidence reported a null association.21 However, there is evidence suggesting a long latency effect for marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation. In analyses within 2 large US cohorts, members of our group reported that although most recent marine ω-3 fatty acid intake was not associated with CRC risk, the intake assessed 10 years or more prior to CRC diagnosis tended to be associated with lower disease risk.4 Similar results have been reported in other studies.5,22 These data provided the rationale for the present ancillary study in VITAL on the effect of ω-3 supplementation on conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, 2 major groups of CRC precursors.

Our null results contrast with several observational studies that have reported a beneficial association between higher dietary intake or plasma levels of marine ω-3 fatty acids and lower risk of colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 However, the observational design of those studies makes it difficult to exclude the possibility of confounding biases. Moreover, most of the previous studies are retrospective case-control studies, which are prone to recall bias or reverse causality.7,8,11,12 To our knowledge, the present study represents the first investigation on ω-3 supplementation and colorectal polyps in a usual-risk population. The uniformly null associations across different histopathologic subtypes and characteristics of polyps suggest that ω-3 supplementation of 1 g per day is unlikely to confer a benefit among individuals at average risk of CRC. However, our findings do not rule out a potential benefit of marine ω-3 fatty acid either at higher doses or in high-risk populations, as reported in previous studies of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis14 or with established CRC.23,24,25 Moreover, in the recent Seafood trial of 709 patients after removal of high-risk adenomas, supplementation with 2 g of EPA per day did not reduce adenoma detection rate but did decrease the number of colorectal adenomas detected per patient at 1-year colonoscopy surveillance.15 There are, however, important differences between the VITAL and the Seafood trials related to the study setting (no protocol-mandated colonoscopy vs mandated colonoscopy screening and surveillance), population (general population vs individuals with a history of high-risk adenomas), and EPA dose and duration. Thus, further studies are needed to confirm the Seafood trial results and examine the potential utility of marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation in the setting of colonoscopy surveillance for prevention of postcolonoscopy neoplasia.26

When stratified by race/ethnicity, we found that the inverse association of ω-3 treatment with risk of conventional adenomas was restricted to African American persons. This racial difference cannot be explained by the variation in ω-3 status prior to randomization because baseline plasma levels of EPA and DHA and fish intake did not show major differences across racial/ethnic groups. Similar racial differences in the effects of ω-3 have been reported in the same trial with respect to myocardial infarction.16 Although these findings may be attributable to chance, it is possible that some biological mechanisms, possibly common to CRC and cardiovascular diseases, may underlie the greater benefit of marine ω-3 fatty acid in African American individuals. Indeed, the bioavailability and metabolism of ω-3 fatty acid are known to be associated with genetic variants whose distributions vary greatly by race/ethnicity.27,28,29 Evolutionary analysis has found that a genetic signature associated with marine ω-3 fatty acid metabolism is positively selected in African populations and provides an advantage for more efficient synthesis and metabolism of marine ω-3 fatty acid when food sources are in limited supply.30,31 In addition to genetics, other racial/ethnic differences in environmental or behavioral factors may play a role, such as the higher rate of obesity and lower uptake of CRC screening among African American persons than among other racial/ethnic groups (eTable 1 in Supplement 2), although we did not find any modification by lifestyle factors or history of colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy to the ω-3–polyp association. Given the limited data, further studies on the potential racial/ethnic difference in the effects of marine ω-3 fatty acid supplementation on colorectal neoplasia are needed.

In addition to a racial difference, we found that ω-3 treatment might lower risk of adenomas among individuals with a low plasma ω-3 index at randomization. Although these findings need to be interpreted cautiously owing to multiple testing and should be confirmed in further studies, they are consistent with the notion that marine ω-3 fatty acid may confer anti-CRC benefits, through its immunomodulatory properties or alterations in cell signaling, among individuals with low internal exposures to marine ω-3 fatty acids because of limited dietary intake or inefficient absorption.32 A similar interaction between ω-3 supplementation and baseline ω-3 status (fish consumption) was found for cardiovascular events in VITAL.16

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths, including the randomized clinical trial design, large sample of average-risk individuals of racial/ethnic diversity, high adherence to the intervention regimen, assessment of baseline plasma ω-3 levels in 60% of the participants, and collection of detailed covariate data that allowed for subgroup analyses. Several limitations of the study should be noted as well. First, because regular screening endoscopy was not protocol mandated, it is likely that not all polyps were diagnosed. In addition, because of resource constraints, we were able to perform medical record reviews only for a subset of participants with reported polyps whose physicians recommended they undergo surveillance colonoscopy within 5 years. However, given the randomization design and large sample size, no difference between the treatment groups was found in the proportion of medical record review among the self-reported polyp cases (35% for both groups) and the proportion of endoscopic examination of participants during the study period (43% vs 44% for treatment vs placebo groups), making bias unlikely. Second, given the large number of secondary analyses, these findings should be interpreted cautiously. Third, because a single-dose level of marine ω-3 fatty acid was used in the trial, we were unable to assess a dose-response relationship.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that ω-3 supplementation of 1 g per day was not associated with risk of a colorectal premalignant lesion. A potential benefit of ω-3 supplementation among African American persons or individuals with low baseline ω-3 status requires further investigation.

Trial Protocol

eFigure. Flowchart of Colorectal Polyp Identification in VITAL

eTable 1. Association of Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation With Risk of Conventional Adenomas and Serrated Polyps According to Histopathological Features

eTable 2. Stratified Association of Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation With Risk of Conventional Adenoma and Serrated Polyp

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Participants According to Race/Ethnicity

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cockbain AJ, Toogood GJ, Hull MA. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2012;61(1):135-149. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.233718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turk HF, Chapkin RS. Membrane lipid raft organization is uniquely modified by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2013;88(1):43-47. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song M, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, et al. Dietary intake of fish, ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids and risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective study in U.S. men and women. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(10):2413-2423. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler LM, Wang R, Koh WP, Stern MC, Yuan JM, Yu MC. Marine n-3 and saturated fatty acids in relation to risk of colorectal cancer in Singapore Chinese: a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(3):678-686. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strum WB. Colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1065-1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1513581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghadimi R, Kuriki K, Tsuge S, et al. Serum concentrations of fatty acids and colorectal adenoma risk: a case-control study in Japan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9(1):111-118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rifkin SB, Shrubsole MJ, Cai Q, et al. PUFA levels in erythrocyte membrane phospholipids are differentially associated with colorectal adenoma risk. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(11):1615-1622. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517001490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cottet V, Collin M, Gross AS, et al. Erythrocyte membrane phospholipid fatty acid concentrations and risk of colorectal adenomas: a case-control nested in the French E3N-EPIC cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(8):1417-1427. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh K, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. Dietary marine n-3 fatty acids in relation to risk of distal colorectal adenoma in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(4):835-841. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pot GK, Geelen A, van Heijningen EM, Siezen CL, van Kranen HJ, Kampman E. Opposing associations of serum n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids with colorectal adenoma risk: an endoscopy-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(8):1974-1977. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murff HJ, Shrubsole MJ, Cai Q, et al. Dietary intake of PUFAs and colorectal polyp risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):703-712. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Wu K, Ogino S, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT, Song M Association between risk factors for colorectal cancer and risk of serrated polyps and conventional adenomas. Gastroenterology 2018;155(2):355-373. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West NJ, Clark SK, Phillips RK, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces rectal polyp number and size in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2010;59(7):918-925. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.200642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hull MA, Sprange K, Hepburn T, et al. ; seAFOod Collaborative Group . Eicosapentaenoic acid and aspirin, alone and in combination, for the prevention of colorectal adenomas (seAFOod Polyp Prevention trial): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2583-2594. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31775-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. ; VITAL Research Group . Marine n-3 fatty acids and prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassuk SS, Manson JE, Lee IM, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL). Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:235-243. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manson JE, Bassuk SS, Lee IM, et al. The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL): rationale and design of a large randomized controlled trial of vitamin D and marine omega-3 fatty acid supplements for the primary prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(1):159-171. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ; American Heart Association. Nutrition Committee . Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106(21):2747-2757. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038493.65177.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris WS, Von Schacky C. The Omega-3 Index: a new risk factor for death from coronary heart disease? Prev Med. 2004;39(1):212-220. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen GC, Qin LQ, Lu DB, et al. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids intake and risk of colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(1):133-141. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0492-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall MN, Chavarro JE, Lee IM, Willett WC, Ma J. A 22-year prospective study of fish, n-3 fatty acid intake, and colorectal cancer risk in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(5):1136-1143. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Blarigan EL, Fuchs CS, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Marine ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid and fish intake after colon cancer diagnosis and survival: CALGB 89803 (Alliance). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(4):438-445. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song M, Zhang X, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Marine ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. Gut. 2017;66(10):1790-1796. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cockbain AJ, Volpato M, Race AD, et al. Anticolorectal cancer activity of the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid. Gut. 2014;63(11):1760-1768. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dekker E, Kaminski MF. Take a pill for no more polyps: is it that simple? Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2519-2521. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hester AG, Murphy RC, Uhlson CJ, et al. Relationship between a common variant in the fatty acid desaturase (FADS) cluster and eicosanoid generation in humans. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(32):22482-22489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.579557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sergeant S, Hugenschmidt CE, Rudock ME, et al. Differences in arachidonic acid levels and fatty acid desaturase (FADS) gene variants in African Americans and European Americans with diabetes or the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(4):547-555. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chilton FH, Dutta R, Reynolds LM, Sergeant S, Mathias RA, Seeds MC. Precision nutrition and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: a case for personalized supplementation approaches for the prevention and management of human diseases. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):E1165. doi: 10.3390/nu9111165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathias RA, Fu W, Akey JM, et al. Adaptive evolution of the FADS gene cluster within Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ameur A, Enroth S, Johansson A, et al. Genetic adaptation of fatty-acid metabolism: a human-specific haplotype increasing the biosynthesis of long-chain omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(5):809-820. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song M, Nishihara R, Cao Y, et al. Marine ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and risk of colorectal cancer characterized by tumor-infiltrating T cells. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1197-1206. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure. Flowchart of Colorectal Polyp Identification in VITAL

eTable 1. Association of Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation With Risk of Conventional Adenomas and Serrated Polyps According to Histopathological Features

eTable 2. Stratified Association of Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation With Risk of Conventional Adenoma and Serrated Polyp

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Participants According to Race/Ethnicity

Data Sharing Statement