Key Points

Question

Do patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have excess mortality compared with the general population?

Findings

This cohort study of 4893 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy recruited between 1980 and 2013 at 7 European referral centers comparing their survival (a composite end point of all-cause mortality, heart transplant, and aborted sudden cardiac death) with that of the general population found that patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy had excess mortality throughout life that improved with time. Female patients had higher excess mortality than male patients throughout the age spectrum, whereas mortality among male patients older than 60 years was similar to that of the general population.

Meaning

Mortality rates in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy remain higher than those of the general population but have improved in contemporary cohorts.

Abstract

Importance

It is unclear whether hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) conveys excess mortality when compared with the general population.

Objective

To compare the survival of patients with HCM with that of the general European population.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of 4893 consecutive adult patients with HCM presenting at 7 European referral centers between 1980 and 2013. The data were analyzed between April 2018 and August 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Survival was compared using standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) calculated with data from Eurostat, stratified by study period, country, sex, and age, and using a composite end point in the HCM cohort of all-cause mortality, aborted sudden cardiac death, and heart transplant.

Results

Of 4893 patients with HCM, 3126 (63.9%) were male, and the mean (SD) age at presentation was 49.2 (16.4) years. During a median follow-up of 6.2 years (interquartile range, 3.1-9.8 years), 721 patients (14.7%) reached the composite end point. Compared with the general population, patients with HCM had excess mortality throughout the age spectrum (SMR, 2.0, 95% CI, 1.48-2.63). Excess mortality was highest among patients presenting prior to the year 2000 but persisted in the cohort presenting between 2006 and 2013 (SMR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.55-2.18). Women had higher excess mortality than men (SMR, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.38-2.97; vs SMR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.52-1.85; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients referred to European specialty centers, HCM was associated with significant excess mortality through the life course. Although there have been improvements in survival with time, potentially reflecting improved treatments for HCM, these findings highlight the need for more research into the causes of excess mortality among patients with HCM and for better risk stratification.

This cohort study compares survival among the general European population with that of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who were recruited from 7 European specialty referral centers.

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common genetic heart disease with a population prevalence ratio of approximately 1:500.1 Early HCM cohort studies reported a high mortality due to sudden cardiac death (SCD) and heart failure but were limited by a significant selection bias.2 Contemporary survival studies have shown that the prognosis for most individuals with the disease may be better than described previously, particularly when it is managed in line with current clinical practice guidelines,3 but the excess mortality that HCM conveys when compared with the general population remains unclear.4,5 We sought to compare the survival of patients with HCM in a large multicenter European cohort with that observed in the general population using contemporaneous country, age-stratified, and sex-stratified European mortality data.

Methods

Study Design and Overview

The present study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.6 Data from a retrospective, multicenter, longitudinal cohort—the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcome Investigators7,8—were used for this cohort study. The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results. The study was approved by the local ethics committees in all centers with the exception of the Institute of Cardiology at the University of Bologna (Italy), where the committee was informed, but approval was not required under local research governance arrangements. Patients at A Coruña University Hospital (Spain), First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens (Greece), University Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca (Spain), and Monaldi Hospital (Italy) provided written informed consent. Patients at The Heart Hospital (UK), Hospital Universitario Puerta del Hierro (Spain) and Institute of Cardiology at the University of Bologna (Italy) did not provide written informed consent because it was not required by their ethics committees.

Study Population and Participating Centers

The study cohort consisted of all consecutive patients with HCM and follow-up evaluated between 1980 and 2013 at 7 European centers: (1) The Heart Hospital, London, United Kingdom; (2) A Coruña University Hospital, A Coruña, Spain; (3) Unit of Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Greece; (4) Institute of Cardiology, Alma Mater University of Bologna, Italy; (5) University Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia, Spain; (6) Monaldi Hospital, Università della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli,” Italy; and (7) Hospital Universitario Puerta del Hierro, Madrid, Spain. Data from the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcome Investigators cohort have been reported in other studies.7,9,10 Only adult patients (≥16 years of age) were included. We defined HCM as a maximum left ventricular (LV) wall thickness of 15 mm or more unexplained solely by loading conditions or in accordance with published criteria for the diagnosis of disease in relatives of patients with unequivocal disease.11 Patients known to have inherited metabolic diseases or syndromic causes of HCM were excluded.

Patient Assessment and Data Collection

Patients were reviewed every 6 to 12 months or earlier if there was a change in symptoms. At presentation, all patients underwent clinical assessment, pedigree analysis, physical examination, resting and ambulatory electrocardiography, and transthoracic echocardiography. Each center collected data independently using the same methods.

Definition of Baseline Variables

Family history of SCD was defined as a history of SCD in 1 or more first-degree relatives younger than 40 years of age or SCD in a first-degree relative with confirmed HCM at any age (postmortem or antemortem diagnosis).12 Maximum LV wall thickness was defined as the greatest thickness in the anterior septum, posterior septum, lateral wall, and posterior wall of the LV, measured at the level of the mitral valve, papillary muscles, and apex in the parasternal short-axis plane using 2-dimensional echocardiography.13 The LV ejection fraction was calculated using the Teichholz method.14 The left atrial diameter was determined by M-mode or 2-dimensional echocardiography in the parasternal long axis plane.15 The maximum LV outflow gradient was determined at rest and with Valsalva provocation (irrespective of concurrent medical treatment) using pulsed and continuous wave Doppler from the apical 3- and 5-chamber views. Peak outflow tract gradients were determined using the modified Bernoulli equation (gradient = 4V2, where V is the peak aortic outflow velocity on continuous wave Doppler).12 Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia was defined as 3 or more consecutive ventricular beats at a rate of at least 120 per minute and less than 30 seconds in duration on Holter monitoring (minimum duration 24 hours) at or prior to first evaluation.16 Syncope was defined as a history of unexplained syncope at or prior to first evaluation.15

Outcomes

The cause of death was ascertained by experienced cardiologists (M.L., C.O., O.P.G., J.R.G., L.M., A.A., C.R., E.B., P.G.-P., G.L., and P.M.E.) at each center using hospital and primary health care records, death certificates, postmortem reports, and interviews with witnesses (relatives and physicians). We defined SCD as witnessed sudden death with or without documented ventricular fibrillation or death within 1 hour of new symptoms or nocturnal deaths with no antecedent history of worsening symptoms.13 Successful resuscitation from ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia during follow-up and appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) shock therapy were considered equivalent to SCD,16,17,18,19 but antitachycardia pacing was not. Data on aborted SCD or sustained ventricular tachycardia (at a rate of 120 beats or more per minute lasting more than 30 seconds) preceding the presentation were collected, but not included in the study end point. Other cardiovascular (CV) death included stroke, heart failure death, and procedure-associated death. Heart transplant was considered equivalent to death from heart failure. The follow-up time for each patient was the time from diagnosis to the primary composite end point, end of study period, or last follow-up date. Patients who were alive at the end of study period or who were lost to follow-up were treated as censored.

The main survival analysis was based on a composite end point consisting of all-cause mortality, aborted SCD, and heart transplant. Overall standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were also calculated according to time of presentation (before 2001, 2001-2005, and 2006 and onward) and referral center. A secondary survival analysis was conducted, including appropriate ICD shock therapy in the composite end point.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed from April 2018 to August 2019 with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0 (IBM Corp), and Stata, version 12, (StataCorp). For descriptive statistics, variables are expressed as mean (SD), median (interquartile range, IQR), or counts and percentages, as appropriate. The follow-up time for each patient was calculated from the date of first evaluation at participating centers to the date of the relevant end point or to the date of the most recent evaluation. For comparisons between groups, the χ2 test was used for categorical variables, and t tests or Mann-Whitney tests or 1-way analysis of variance was used for continuous variables, as appropriate. Methods for the Cox proportional hazards modeling are reported in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

We calculated SMRs as the ratio of actual deaths to expected deaths using data from Eurostat20 extracted on August 18, 2017. Eurostat is the statistical office of the European Union that supplies the public and European institutions with data and statistics, with the objective of defining, implementing, and analyzing European Community policies. Expected mortality was based on the mortality rates from the appropriate period for each center and was stratified by country, sex, and age at the end of follow-up. Patient age at the end of follow-up was used for the calculation of expected mortality based on yearly mortality rates by age in the general population. For the calculation of expected deaths, each patient contributed person-years to the different age categories he or she was assigned to from presentation and throughout follow-up (eg, a patient who presented at 21 years of age and died at 32 years of age contributed 5 years of follow-up to the 21-25 age group, 5 years to the 26-30 age group, and 1 year to the 31-35 age group). The SMRs were calculated using the main and secondary composite end points; 95% CIs and comparisons were estimated by Poisson regression. Indirectly adjusted mortality rates were obtained by multiplying the crude rate of the standard population by the SMRs, and 95% CIs were calculated as previously described.21

Results

The study population consisted of 4893 patients, 3126 (63.9%) were males, the mean (SD) age at presentation was 49.2 (16.4) years, and patients were followed up for a total of 34 173.62 person-years. Table 1 reports the baseline characteristics of the study population, and eFigure 1 in the Supplement shows the distribution by age at presentation.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at presentation, mean (SD), y | 49.2 (16.4) |

| Male sex | 3126 (63.9) |

| Country | |

| Greece | 566 (11.6) |

| Spain | 1497 (30.6) |

| Italy | 733 (15.0) |

| United Kingdom | 2097 (42.9) |

| Family history of sudden death, No./total No. (%) | 1127/4752 (23.7) |

| Previous VF/sustained VT | 134 (2.7) |

| NYHA functional classification | |

| I | 2560 (54.6) |

| II | 1613 (34.4) |

| III/IV | 514 (11.0) |

| Unexplained syncope, No./total No. (%) | 725/4846 (15.0) |

| Nonsustained VT on Holter, No./total No. (%) | 924/4204 (22.0) |

| ICD at baseline or during follow-up | 816 (16.7) |

| Previous atrial fibrillation | 653 (13.3) |

| Hypertension, No./total No. (%) | 1446/4783 (30.2) |

| Maximum LV wall thickness, median (IQR), mm | 19 (16-22) |

| LV end-diastolic diameter, mean (SD), mm | 44.8 (6.5) |

| LV ejection fraction ≤50%, No./total No. (%) | 396/4428 (8.9) |

| Maximum LVOT gradient, median (IQR), mm Hg | 9 (4-50) |

| LVOT gradient, No./total No. (%) | |

| >30 mm Hg | 1372/4238 (32.4) |

| >50 mm Hg | 1087/4238 (25.6) |

| Left atrial diameter, mean (SD), mm | 44.1 (7.8) |

Abbreviations: ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range; LV, left ventricle; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Main Survival Analysis

After a median follow-up of 6.2 years (IQR, 3.1-9.8), 721 patients (14.7%) reached the composite study end point. Of these, 168 patients (3.4%) met the SCD or equivalent end point (SCD, 138 [2.8%]; aborted SCD, 30 [0.6%]); 213 patients (4.4%) met the heart failure (HF) death or equivalent end point (HF death, 129 [2.6%]; cardiac transplant, 84 [1.7%]); 106 patients (2.2%) died of other CV causes; 212 patients (4.3%) died of non-CV causes, and 22 patients (0.5%) died of unknown causes. During follow-up, 390 patients (8%) underwent septal reduction treatment (septal myectomy, 282 [5.8%]; alcohol septal ablation, 93 [1.9%]; both procedures, 15 [0.3%]).

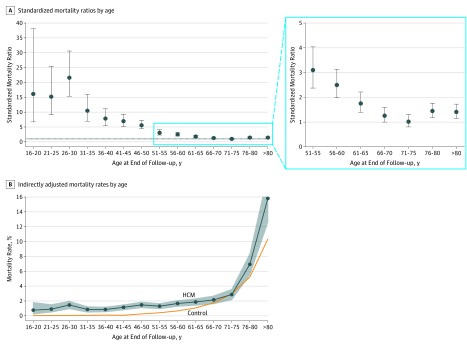

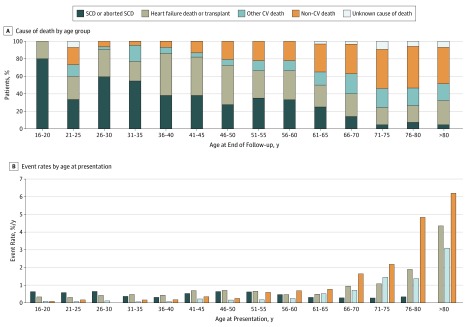

Overall, patients with HCM had excess mortality compared with the general population (SMR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.48-2.63). Figure 1A shows the calculated SMR by age, with values higher than 1 indicating excess mortality compared with the general population; Figure 1B reports the indirectly adjusted mortality rates by age in the study population. The main cause of death in younger patients was SCD (or equivalent), but this accounted for a progressively smaller percentage of total deaths with advancing age, whereas HF death or cardiac transplantation accounted for a similar proportion of events throughout the age spectrum. Other CV and non-CV causes increased progressively after 45 years of age (Figure 2A). Figure 2B shows the event rates according to age at presentation. The rate of SCD varied with age, whereas the rates of HF death or transplant, other CV, and non-CV death increased after the age of 65 years.

Figure 1. Standardized Mortality Ratios and Indirectly Adjusted Mortality Rates Reported by Age in the Study Population.

Values higher than 1 indicate excess mortality compared with the general population. B, For the group older than 80 years of age, the adjusted mortality upper 95% CI limit is 19.0%. HCM indicates hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; error bars, 95% CIs.

Figure 2. Cause of Death by Age Group and Event Rates According to Age at Presentation in the Study Population.

CV indicates cardiovascular; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

Patients who were first seen prior to 2000 were younger, had more SCD risk factors, and reported heart failure symptoms more frequently. Surgical treatment of LV outflow tract obstruction was more frequent in patients first seen from 2000 and onward, whereas ICD use at baseline or during follow-up was lower in patients first seen in the 1980s, but did not differ thereafter (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Excess mortality was greatest in patients presenting prior to 2000 but persisted in the cohort presenting between 2006 and 2013 (SMR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.55-2.18) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). A subgroup analysis by country showed some differences in baseline characteristics and management, with more frequent septal reduction treatment in the United Kingdom and higher use of ICDs in Italy and the United Kingdom (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Despite differences in event rates (eg, a higher rate of SCD or aborted SCD in Italy, and a higher rate of HF death or cardiac transplant in Italy and Spain) excess SMR was present across all centers (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Sex and Mortality

Male and female patients had different clinical profiles (Table 2) at baseline evaluation. Females were older at presentation, more symptomatic (New York Heart Association functional classification III/IV, 17.1% vs 7.5%), and more likely to have a family history of SCD and a history of syncope. The LV wall thickness and systolic function were similar in men and women, but women were more likely to have LV outflow tract obstruction. Women were more likely to have or to develop atrial fibrillation during the study and have a history of hypertension.

Table 2. Characteristics of the Study Population by Sex.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 1767) | Male (n = 3126) | ||

| Age at presentation, mean (SD), y | 52.9 (17.2) | 47.1 (15.6) | <.001 |

| Follow-up duration, median (IQR), y | 5.9 (2.8-9.6) | 6.4 (3.2-10.0) | .002 |

| Family history of sudden death, No./total No. (%) | 467/1709 (27.3) | 660/3043 (21.7) | <.001 |

| Previous VF/sustained VT | 40 (2.3) | 94 (3.0) | .13 |

| NYHA functional classification | |||

| I | 695 (41.2) | 1865 (62.1) | <.001 |

| II | 703 (41.7) | 910 (30.3) | |

| III/IV | 288 (17.1) | 226 (7.5) | |

| Unexplained syncope, No./total No. (%) | 289/1746 (16.6) | 436/3100 (14.1) | .02 |

| Nonsustained VT on Holter, No./total No. (%) | 296/1496 (19.8) | 628/2708 (23.2) | .01 |

| ICD at baseline or during follow-up | 281 (15.9) | 535 (17.1) | .28 |

| Hypertension, No./total No. (%) | 616/1732 (35.6) | 830/3051 (27.2) | <.001 |

| Maximum LV wall thickness, median (IQR), mm | 18 (16-22) | 19 (16-22) | .003 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter, mean (SD), mm | 42.5 (6.2) | 46.1 (6.3) | <.001 |

| LV ejection fraction, mean (SD), % | 66 (12) | 65 (12) | <.001 |

| LV ejection fraction ≤50%, No./total No. (%) | 132/1593 (8.3) | 264/2835 (9.3) | .27 |

| Maximum LVOT gradient, median (IQR), mm Hg | 10 (4-64) | 8 (4-44) | <.001 |

| LVOT gradient >50 mm Hg, No./total No. (%) | 463/1545 (30.0) | 624/2693 (23.2) | <.001 |

| Left atrial diameter, mean (SD), mm | 43 (7.6) | 44.8 (7.9) | <.001 |

| AF at baseline or during follow-up | 591 (33.4) | 939 (30.0) | .01 |

| Septal myectomy | 118 (6.7) | 179 (5.7) | .18 |

| Alcohol septal ablation | 47 (2.7) | 61 (2.0) | .11 |

| Any septal reduction treatment | 160 (9.1) | 230 (7.4) | .04 |

| Outcomes | |||

| SCD | 36 (2.0) | 102 (3.3) | ND |

| Aborted SCD | 10 (0.6) | 20 (0.6) | |

| Heart failure death | 71 (4.0) | 58 (1.9) | |

| Heart transplant | 38 (2.2) | 46 (1.5) | |

| Other CV death | 51 (2.9) | 55 (1.8) | |

| Non-CV death | 97 (5.5) | 115 (3.7) | |

| Unknown cause | 11 (0.6) | 11 (0.4) | |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CV, cardiovascular; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range; LV, left ventricle; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; ND, not determined; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

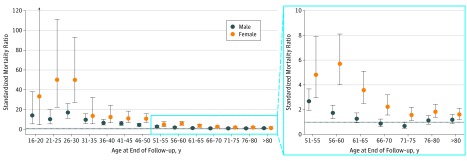

Female patients had higher excess mortality than male patients did (SMR, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.38-2.97 vs SMR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.52-1.85; P < .001). Excess mortality among female patients was present throughout the age spectrum, whereas mortality among male patients older than 60 years was similar to that of the general population (Figure 3). Female sex was independently associated with a worse prognosis after adjusting for baseline differences in a multivariate model (hazard ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.09-1.49; P = .003) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The event rates by sex and age at presentation are reported in eFigure 4 in the Supplement.

Figure 3. Standardized Mortality Ratios by Age and Sex in the Study Population.

For females aged 16 to 20 years, the upper 95% CI limit is 236.6. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Secondary Analysis

After a median follow-up of 6.1 years (IQR, 3.0-9.8 years), 796 patients (16.3%) reached the secondary composite end point. Of these patients, 263 (5.4%) met the SCD or equivalent end point (SCD, 137 [2.8%]; appropriate ICD shock, 96 [2%]; and aborted SCD, 30 [0.6%]); 200 (4.1%) met the HF death or equivalent end point (HF death, 123 [2.5%]; cardiac transplant, 77 [1.6%]), 103 (2.1%) died of other CV causes, 210 (4.3%) died of non-CV causes, and 20 (0.4%) died of unknown causes. Patients with HCM had excess mortality compared with the general population (SMR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.66-2.94), and this excess mortality was greater among female patients (SMR, 2.87; 95% CI, 2.57-3.19; vs SMR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.76-2.11; P < .001) (eFigure 5 in the Supplement). Details regarding missing data are reported in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Discussion

In a large international multicenter referral cohort, we showed that adult patients with HCM had excess mortality compared with the general population. This was highest in women, in whom excess mortality persisted throughout life, whereas men had a similar mortality to the general population beyond the sixth decade of life.

The natural history of HCM is characteristically heterogeneous, ranging from asymptomatic patients who experience no disease-associated morbidity or mortality during their lifetime to those that who die suddenly or develop severe refractory HF.22 Previous studies have reported HCM-associated mortality in specific age groups, with findings similar to those of this study4,23,24; however, to our knowledge, no study has matched patients to the general population with this degree of precision, adjusting for study period, country, age, and sex. A recent report from the Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy HCM registry (more commonly known as SHaRe)25 described lifetime disease burden in association with genotype and suggested that patients with HCM treated in the United States have worse survival than the general US population in the younger (age, 20-29 years) and older (age, 50-69 years) age groups; however, that analysis was not adjusted for factors that could be associated with mortality, such as sex and study period.

Because it is not possible to examine specific causes of cardiovascular death with Eurostat data, we can only speculate on the cause of excess mortality in the HCM population. Consistent with previous studies, we showed that SCD was the predominant cause of death in younger adults with HCM, whereas HF death occurred throughout the life course and became more prevalent in older decades.13,15,17

Overall mortality in the present study was lower than that reported in historical cohorts,2 and when survival was analyzed according to the era of first evaluation, contemporary patients had lower excess mortality compared with the normal population than patients in the earliest cohort. We can only speculate on the explanation, but therapeutic innovation—in particular, ICDs and invasive treatments for LV outflow obstruction—are likely to be important. Differences in baseline patient characteristics may also contribute to the decline in mortality. For example, patients presenting before 2000 were younger, more symptomatic, had greater LV wall thickness, and more frequently had SCD risk factors. Nevertheless, excess mortality was still present in contemporary patients (eFigure 2 in the Supplement), suggesting that more needs to be done to reduce disease-associated complications.

Although sex is considered a cofactor in many outcome studies, relatively few studies have specifically examined its influence on survival in HCM. Recent reports in Chinese and North American populations have reported higher all-cause mortality among female patients26,27 in contrast to other studies that have shown an excess of death from heart failure or stroke in women but no difference in overall survival.28 In the present study, we showed that excess mortality compared with the general population was greater among women than among men and that this excess among women persisted into the later decades of life, in contrast to men aged more than 65 years, who had mortality rates similar to that of the general population. This may well be attributable to increased rates of HF death among women (eFigure 4 in the Supplement), but dedicated studies are needed to investigate this.

Limitations

Because the recruiting centers in this study were all specialized cardiomyopathy units, it is possible that the observed excess mortality reflects a bias toward more symptomatic patients with advanced disease. The higher than expected prevalence of LV dysfunction supports this notion, but this finding could also be artifactual and associated with the use of the Teichholz method for calculating LV ejection fraction.

Determination of the natural history of what are sometimes called community disease populations is challenging owing to variations in diagnostic methods and unreliable case ascertainment. In a recent UK study of linked electronic health records, including a general practice database, a bespoke diagnostic phenotype algorithm was used to identify 1160 individuals with HCM among 3 290 455 eligible people.5 Compared with people in the general population, people with HCM had higher risk of cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. The absolute Kaplan-Meier risks at 3 years were 8.8% for the composite end point of cardiovascular death or heart failure and 8.4% for the composite of cardiovascular death, stroke, or myocardial infarction. These data suggest that the risk of disease-associated complications may actually be higher among patients treated outside referral centers, possibly owing to nonadherence with current HCM guidelines.

Because of the historic nature of the study cohort, baseline cardiac magnetic resonance data were not available. Information on genotype was not collected in the present data set. A degree of survivor bias cannot be excluded, because it is possible that some patients died prior to evaluation in a referral center. Finally, our study was designed to include only baseline phenotypic variables and did not enable us to better characterize HF deaths.

Conclusions

In European referral center cohorts, HCM was associated with excess mortality throughout the life course. Outcome has improved over time, but mortality still exceeds that of the general population in contemporary cohorts. These findings highlight the need for more research into the causes of excess mortality among patients with HCM and for better risk stratification.

eAppendix. Cox Proportional Hazards Modelling and Missing Data

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Study Population According to Era of First Evaluation

eTable 2. Characteristics, Treatment and Outcome of the Study Population by Country

eTable 3. Multivariable Cox Analysis for the Main Survival Analysis (Composite of All-Cause Mortality, Transplantation and Aborted Sudden Cardiac Death)

eFigure 1. Distribution of Study Cohort by Age at Presentation

eFigure 2. Standardized Mortality Ratios According Era of First Evaluation

eFigure 3. Standardized Mortality Ratios According to Centre

eFigure 4. Event rates in the Study Population by Sex, According to Age at Presentation

eFigure 5. Secondary Analysis Including ICD Shocks: Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR) and Indirectly Adjusted Mortality Rates in the Study Population Reported by Age

References

- 1.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Thaman R, et al. Historical trends in reported survival rates in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2006;92(6):785-791. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Rowin EJ. Perspectives on the overall risks of living with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2017;135(24):2317-2319. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, et al. Risk stratification and outcome of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy ≥60 years of age. Circulation. 2013;127(5):585-593. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.136085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pujades-Rodriguez M, Guttmann OP, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, et al. Identifying unmet clinical need in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using national electronic health records. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Pavlou M, et al. ; Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcomes Investigators . A novel clinical risk prediction model for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM risk-SCD). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(30):2010-2020. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HCMRisk.org . Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcomes Investigators. http://www.HCMRisk.org. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 9.Guttmann OP, Pavlou M, O’Mahony C, et al. ; Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcomes Investigators . Predictors of atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2017;103(9):672-678. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guttmann OP, Pavlou M, O’Mahony C, et al. ; Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcomes Investigators . Prediction of thrombo-embolic risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-CVA). Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(8):837-845. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna WJ, Spirito P, Desnos M, Dubourg O, Komajda M. Experience from clinical genetics in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: proposal for new diagnostic criteria in adult members of affected families. Heart. 1997;77(2):130-132. doi: 10.1136/hrt.77.2.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Tomé MT, et al. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(16):1933-1941. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott PM, Poloniecki J, Dickie S, et al. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: identification of high risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(7):2212-2218. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11127463. Accessed November 3, 2016. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic-angiographic correlations in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37(1):7-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1244736. Accessed April 29, 2018. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spirito P, Autore C, Rapezzi C, et al. Syncope and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2009;119(13):1703-1710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Sharma S, Penas-Lado M, McKenna WJ. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an independent marker of sudden death risk in young patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(5):873-879. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00827-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olivotto I, Gistri R, Petrone P, Pedemonte E, Vargiu D, Cecchi F. Maximum left ventricular thickness and risk of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(2):315-321. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02713-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maron MS, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, et al. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(4):295-303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Efthimiadis GK, Parcharidou DG, Giannakoulas G, et al. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction as a risk factor for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(5):695-699. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eurostat. Your key to European statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/home. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- 21.Kahn HA, Sempos CT. Statistical Methods in Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. ; Authors/Task Force members . 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733-2779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children, adolescents, and young adults associated with low cardiovascular mortality with contemporary management strategies. Circulation. 2016;133(1):62-73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in adulthood associated with low cardiovascular mortality with contemporary management strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(18):1915-1928. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho CY, Day SM, Ashley EA, et al. Genotype and lifetime burden of disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: insights from the Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry (SHaRe). Circulation. 2018;138(14):1387-1398. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geske JB, Ong KC, Siontis KC, et al. Women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have worse survival. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(46):3434-3440. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Wang J, Zou Y, et al. Female sex is associated with worse prognosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in China. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivotto I, Maron MS, Adabag AS, et al. Gender-related differences in the clinical presentation and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(3):480-487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Cox Proportional Hazards Modelling and Missing Data

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Study Population According to Era of First Evaluation

eTable 2. Characteristics, Treatment and Outcome of the Study Population by Country

eTable 3. Multivariable Cox Analysis for the Main Survival Analysis (Composite of All-Cause Mortality, Transplantation and Aborted Sudden Cardiac Death)

eFigure 1. Distribution of Study Cohort by Age at Presentation

eFigure 2. Standardized Mortality Ratios According Era of First Evaluation

eFigure 3. Standardized Mortality Ratios According to Centre

eFigure 4. Event rates in the Study Population by Sex, According to Age at Presentation

eFigure 5. Secondary Analysis Including ICD Shocks: Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR) and Indirectly Adjusted Mortality Rates in the Study Population Reported by Age