Abstract

Objective

The objective of this survey was to assess oral hygiene habits and compliance with guidelines for good oral health set forth by the Italian Ministry of Health (IMH).

Subjects and Methods

A sample of 2,200 self-administered questionnaires was sent to four dental clinics across Italy to assess sociodemographic information, oral hygiene habits, frequency of dental visits and services received at previous visits among a population of adult patients.

Results

Of the 2,200 questionnaires, 1,201 (54.6%) were returned. Findings showed that full compliance with the IMH recommendations was low (12%): a small number of patients (n = 223, 18.6%) visited a dentist every 6 months and only 256 (23.5%) brushed their teeth at least twice a day.

Conclusion

Our data showed that regular attendance (at least 1 visit/year) at dental clinics for routine check-up and brushing teeth at least twice a day were poor. Therefore, we recommend that clinicians educate and motivate their patients about the benefits of healthy oral hygiene practices.

Key Words: Compliance, Education, Oral hygiene

Introduction

Regular dental visits and daily oral hygiene are important components of oral health care, which is an integral part of general health. Poor oral health can impact the quality of life and well-being by causing suffering and pain and affect the ability to eat, drink, swallow, maintain proper nutrition, and communicate [1]. Further, the relationship between poor oral health and systemic diseases has been increasingly recognized over the past two decades [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Periodontal disease resulting from poor oral hygiene has been identified as a potential risk factor for type II diabetes [2, 3] and cardiovascular diseases [4, 5], and has also been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes [7] and respiratory disease [8]. Periodontal treatment has been shown to be useful in the prevention of systemic diseases [9].

The Italian Ministry of Health (IMH) recommended brushing at least twice a day with a fluoride toothpaste and one dental check-up per year [10]. Adherence to this oral hygiene regimen is important for maintaining a good standard of oral health and preventing oral and systemic diseases.

Several studies concentrated in Northern European countries have reported on oral hygiene habits, mainly among focused populations such as children, pregnant women or the elderly [11, 12, 13, 14]. Understanding regional oral hygiene practices can guide local public health practitioners and clinicians in targeting high-risk populations and promoting oral care. Accordingly, we decided to analyze oral hygiene practices and assess compliance with the guidelines for good oral health set forth by the IMH among a population of adults attending dental clinics across Italy.

Subjects and Methods

Study Population and Recruitment

The study methods have been described previously [15]. Briefly, questionnaires were sent to the dental departments of four Italian university hospitals (550 per hospital): University of Messina, Umberto I Hospital; University La Sapienza, San Paolo Hospital; University of Milano, and San Raffaele Hospital, University Vita e Salute. Patients were selected sequentially based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) age 18 or older and (2) ability to read, understand and answer the questionnaire. Each participant gave written consent. The IMH approved this study.

Data Collection

The self-administered questionnaire assessed sociodemographic information, oral hygiene habits, frequency of dental visits, and services received at previous visits. Oral hygiene habits such as frequency of brushing (twice a day, once a day, less than once a day), visits to a dentist (at least once every 6 months, every 1–2 years, or when in pain), flossing, and mouthwash use were assessed.

Statistical Analyses

The distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco smoking and heavy alcohol consumption (more than 2 drinks/day) was evaluated. Age was divided into tertiles. Education was measured as the highest level of education attained based on three categories: less than 10 years of school, 10–14 years of school, and having some college (14 years or more of school).

Using the variables ‘brush at least twice a day’, ‘one dental visit/year’ and ‘daily use of fluoride toothpaste’, an oral hygiene variable was created assessing full compliance and partial compliance (‘brush at least twice a day’ or ‘one dental visit/year’ or ‘daily use of fluoride toothpaste’) with the guidelines for good oral hygiene set forth by the IMH. Values 0 (no compliance), 1 (partial compliance) and 2 (full compliance) were then assigned to the oral hygiene variable.

A multinomial (polytomous) logistic regression was initially performed using the oral hygiene variable with levels 0, 1, 2 to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for exposures of interest such as gender, age, education, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption and compliance with the IMH guidelines (no compliance = 0, partial compliance = 1 or full compliance = 2). Trend tests were conducted and because no statistically significant differences (p for trend >0.05) were observed between individuals with partial compliance and full compliance, these two groups (partial compliance and full compliance) were combined, creating a new binary variable: 1 = compliance with any of the three criteria and 0 = lack of compliance with any of the three criteria. Ordinal logistic regression models were used to estimate ORs and 95% CIs to compare noncompliance with partial/full compliance and were adjusted for each hospital. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA, version 10.0 (Stata, College Station, Tex., USA).

Results

Of the 2,200 questionnaires mailed (4 hospitals, 550 questionnaires per hospital), 1,201 (54.6%) were returned. Patients (n = 1,201) ranged in age from 18 to 98 years (median age: 46) and 459 (38.4%) were male. The majority (89.7%) of the study participants were Italian; 304 (25.3%) had completed university, 624 (52.0%) high school and 273 (22.7%) less than 9 years of education. Four hundred and thirty-four (36.1%) participants reported current smoking, and 730 (60.8%) heavy alcohol consumption (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco and alcohol use and oral hygiene habits of Italian dental patients

| Total (n = 1,201) | |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 735 (61.6) |

| Male | 459 (38.4) |

| Age category | |

| 18–35 | 266 (22.1) |

| 36–49 | 475 (39.6) |

| ≥50 | 460 (38.3) |

| Median | 46 |

| Intraquartile range | 37–54 |

| Education, years | |

| <10 | 270 (22.7) |

| 10–13 | 618 (52.0) |

| ≥14 | 300 (25.3) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 594 (52.6) |

| Former | 127 (11.2) |

| Current | 408 (36.1) |

| Heavy alcohol consumption | |

| Never | 471 (39.2) |

| Ever | 730 (60.8) |

| Oral hygiene habits | |

| Daily fluoride toothpaste | |

| Yes | 900 (74.9) |

| No | 301 (25.1) |

| Daily flossing | |

| Yes | 160 (13.3) |

| No | 1,041 (86.7) |

| Toothbrushing frequency | |

| 1/day | 811 (74.4) |

| 2/day | 94 (8.6) |

| >2/day | 162 (14.9) |

| Rarely/never | 23 (2.1) |

| Mouthwash use frequency | |

| 1/day | 223 (18.6) |

| 2/day | 22 (1.8) |

| >2/day | 4 (0.3) |

| Rarely/never | 952 (79.3) |

| Dental clinic visits | |

| Frequency of dental visits | |

| 6 months | 224 (18.6) |

| Annually | 303 (25.2) |

| Biennially | 463 (38.6) |

| Paina | 211 (17.6) |

| Reason for dental visitb | |

| Check-up | 419 (53.6) |

| Ongoing treatment | 189 (24.2) |

| Pain | 174 (22.2) |

Figures in parentheses are percentages.

Patients visiting a dentist only when in pain.

More than 10% data were missing.

When oral hygiene habits were considered (table 1), the majority (n = 894, 74.4%) reported brushing daily; 94 (8.6%) and 162 (14.9%) reported brushing twice a day or more, respectively. Ninety (75%) reported brushing with fluoride toothpaste; 160 (13.3%) used dental floss regularly. Two hundred and forty-nine (20.7%) of the individuals used mouth-rinsing products. Four hundred and sixty-three (38.6%) reported going to the dentist every 2 years, 224 (18.6%) every 6 months, 303 (25.2%) annually (table 1). Among dental clinic attendees, 419 (53.6%) reported visiting dental clinics for a routine check-up and 174 (22.2%) consulted a dentist only when in pain.

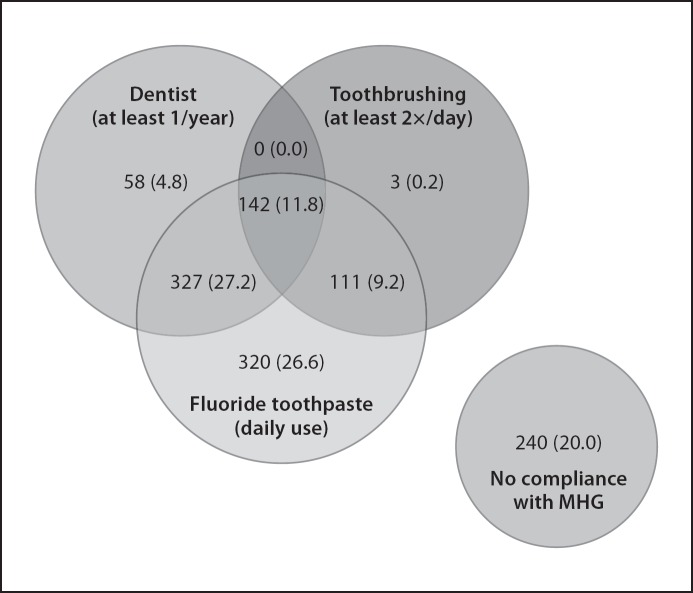

Regarding brushing, toothpaste use and dental visits, 142 (11.8%) followed the IMH guidelines exactly and 240 (20%) did not comply with any of the recommendations. However, 327 (27.2%) complied partially since they visited a dentist at least once a year and used a fluoridated toothpaste but did not satisfy the IMH criteria because they reported brushing less than twice a day. One hundred and eleven (9.2%) brushed in the recommended manner but did not attend a dental clinic as frequently as recommended (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of 1,201 patients according to the IMH Guidelines for Oral Hygiene (MHG). These guidelines recommend toothbrushing at least twice a day with a fluoride toothpaste and one dental check-up per year.

Regarding full/partial compliance compared to noncompliance for IMH guidelines, male patients were 2 times more likely to comply partially/fully with the IMH guidelines (OR 1.9; 95% CI 1.4–2.7; p < 0.01) (table 2). Compliance was similar across age groups (p = 0.90). Education did not affect oral hygiene habits (p = 0.77) and no association was found between tobacco smokers and oral hygiene habits (OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.7–1.3; p = 0.60). Heavy alcohol consumption did not change a patient's oral hygiene behavior (OR: 0.6; 95% CI 0.5–0.8; p = 0.03). Adjustment for hospital did not affect reported associations. Finally, self-reported oral hygiene habits were similar among individuals returning for ongoing treatment versus regular check-ups, and no statistically significant differences were observed between Italian and foreign individuals.

Table 2.

Logistic regression model for the associations with the IMH Guidelines for Oral Hygiene

| Total (n = 1,201) | No compliance (n = 240) | Full and partial compliancea (n = 961) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORb (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.01 | |||||

| Female | 735 (61.6%) | 176 (23.9%) | 559 (76.1%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Male | 459 (38.4%) | 63 (13.7%) | 396 (86.3%) | 1.9 (1.4–2.7) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | |

| Age category | 0.90 | |||||

| 18–35 | 266 (22.1%) | 34 (12.8%) | 232 (87.2%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 36–49 | 475 (39.6%) | 129 (27.2%) | 346 (72.8%) | 0.4 (0.1–0.9) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | |

| ≥50 | 460 (38.3%) | 77 (16.7%) | 383 (83.3%) | 0.7 (0.4–1.6) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | |

| Education, years | 0.77 | |||||

| <10 | 270 (22.7%) | 58 (21.5%) | 212 (78.5%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 10–13 | 618 (52.0%) | 121 (19.6%) | 497 (80.4%) | 1.1 (0.7–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.9) | |

| ≥14 | 300 (25.3%) | 58 (19.3%) | 242 (80.7%) | 1.1 (0.6–1.3) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | |

| Current smoker | 0.60 | |||||

| No | 721 (63.9%) | 149 (20.7%) | 572 (79.3%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 408 (36.1%) | 79 (19.4%) | 321 (80.6%) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.4) | |

| Heavy alcohol consumption | 0.03 | |||||

| Never | 471 (39.2%) | 119 (25.3%) | 352 (74.7%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Ever | 730 (60.8%) | 121 (16.6%) | 609 (83.4%) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

The IMH Guidelines for Oral Hygiene recommend brushing at least twice a day with a fluoride toothpaste and one dental checkup per year (full compliance). Partial compliance was considered when at least one of the guidelines was fulfilled.

OR adjusted for country.

Discussion

Our findings showed that full compliance with the IMH recommendations was low (12%). The majority of patients complied partially and 20% of the individuals did not follow any of the three recommendations. Poor oral hygiene is associated with dental caries, periodontal diseases and may have an impact on overall health. Good oral hygiene practices including brushing and flossing can prevent gingivitis and control advanced periodontal lesions. A recent study showed that self-reported poor oral hygiene (never/rarely brushed) was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio 1.7, 95% CI 1.3–2.3; p < 0.001, after adjustment for relevant confounders) [16]. These data underscore the importance of good oral hygiene among patients.

Regular attendance (at least 1 visit/year) at dental clinics for routine check-up was poor (44%). In the literature, reported reasons for infrequent dental visits are cost (38%), lack of perceived need (27%), and fear (17%) [17]. A lower rate (21%) of the individuals brushed at least twice a day, unlike other studies where higher rates (27.5%) [18] and 62% [19] of brushing at least twice a day were observed. In our study, males' compliance was higher compared to female patients', probably because men overestimated their oral hygiene practices. However, besides gender, no other association with compliance was observed among the factors investigated. Thus, broad educational messaging to everyone is necessary. It is important to note that our study population was comprised of patients attending dental clinics that promote oral health. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings may not extend to the general population. Also, the low response rate and use of self-reports may have introduced a systematic bias. It would have been interesting to be able to contact nonresponders and ascertain why they did not respond to the questionnaire. Finally, respondents might have provided responses that they believed were more desirable for the purpose of this study [20]. If this occurred, compliance with the IMH recommendations could be even lower than 12%. Health care professionals, business leaders, government and insurance companies all need to collaborate to improve access to dental services. Population-directed strategies for oral health promotion and education should be considered in order to further improve the oral hygiene practices of the entire population, lead to better compliance and minimize the risk of oral diseases.

Conclusion

There was self-reported low compliance with IMH recommendations among dental patients in Italy. Therefore, we recommend that oral health care professionals help their patients develop behavioral patterns that include brushing more often as well as visiting a dentist regularly for preventative measures.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported through a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ministero del Lavoro, della salute e delle politiche sociali, CCM).

References

- 1.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31((suppl 1)):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor GW, Borgnakke WS. Periodontal disease: associations with diabetes, glycemic control and complications. Oral Dis. 2008;14:191–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khader YS, Dauod AS, El-Qaderi SS, Alkafajei A, Batayha WQ. Periodontal status of diabetics compared with nondiabetics: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications. 2006;20:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, Genco R, Goldfine A, Libby P, Offenbacher S, Ridker PM, Van Dyke TE, Roberts WC. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology editors' consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1021–1032. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.097001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahekar AA, Singh S, Saha S, Molnar J, Arora R. The prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2007;154:830–837. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varon FN. Effect of periodontitis on overt nephropathy and end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes: response to Shultis et al. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:e138. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1579. author reply e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobetsis YA, Barros SP, Offenbacher S. Exploring the relationship between periodontal disease and pregnancy complications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137((suppl)):7S–13S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Zhou X, Zhang J, Zhang L, Song Y, Hu FB, Wang C. Periodontal health, oral health behaviours, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:750–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seymour RA. Does periodontal treatment improve general health? Dent Update. 2010;37:206–208. doi: 10.12968/denu.2010.37.4.206. 210–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministero del Lavoro della Salute e delle Politiche Sociali. Linee guida nazionali per la promozione della salute orale e la prevenzione delle patologie orali in età evolutiva. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bush HM, Dickens NE, Henry RG, Durham L, Sallee N, Skelton J, Stein PS, Cecil JC. Oral health status of older adults in Kentucky: results from the Kentucky Elder Oral Health Survey. Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2010.00154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronis DL, Lang WP, Farghaly MM, Ekdahl SM. Preventive oral health behaviors among Detroit-area residents. J Dent Hyg. 1994;68:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahlnacke K, Unell L, Soderfeldt B, Ekback G, Ordell S. Self-perceived oral health among 65 and 75 year olds in two Swedish counties. Swed Dent J. 2010;34:107–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hullah E, Turok Y, Nauta M, Yoong W. Self-reported oral hygiene habits, dental attendance and attitudes to dentistry during pregnancy in a sample of immigrant women in North London. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:405–409. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villa A, Kreimer AR, Pasi M, Polimeni A, Cicciù D, Strohmenger L, Gherlone E, Abati S. Oral cancer knowledge: a survey administered to patients in dental departments at large Italian hospitals. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:505–509. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0189-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Oliveira C, Watt R, Hamer M. Toothbrushing, inflammation, and risk of cardiovascular disease: results from Scottish Health Survey. BMJ. 2010;340:c2451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dionne RA, Gordon SM, McCullagh LM, Phero JC. Assessing the need for anesthesia and sedation in the general population. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:167–173. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang HY, Bian JY, Zhang BX. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of adults in China. Int Dent J. 2005;55:231–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shammari KF, Al-Ansari JM, Al-Khabbaz AK, Dashti A, Honkala EJ. Self-reported oral hygiene habits and oral health problems of Kuwaiti adults. Med Princ Pract. 2007;16:15–21. doi: 10.1159/000096134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkes KR. Social desirability, defensiveness and self-report psychiatric inventory scores. Psychol Med. 1980;10:735–742. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700055021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]