Abstract

Background:

The rising costs of health care in the United States are unsustainable and gaps in physician knowledge of how to provide care at a lower cost remains a contributing factor. It has been suggested that learning about health care costs should be incorporated into existing, already overburdened medical school curricula.

Objective:

To increase the discussion of health care costs among first and second year medical students, we added a component of health care cost education to an existing problem/case-based learning (PBL/CBL) program without adding curricular time.

Design:

A total of 98 medical students participated in this study throughout the first 2 years of their educational program. Students were charged with researching and discussing health care cost topics as part of their weekly PBL/CBL case conferences. Faculty facilitators tracked each student’s participation in discussions of health care cost topics as well as how often students initiated new conversations about health care cost topics during their case conferences.

Results:

100% of students engaged in conversations about health care cost topics throughout their first and second year PBL/CBL program. In addition, students increasingly initiated new conversations about health care cost topics as they progressed through their courses from the first to the second year (R2 = 0.887, P < .01).

Conclusions:

Sensitizing medical students early during their educational program to incorporate health care cost topics into their PBL/CBL case conferences proved an effective means for having them engage in conversations related to health care costs. These results offer a new, time-efficient option for incorporating health care cost topics for schools with PBL/CBL programs.

Keywords: Health care costs, health care economics, problem-based learning, high-value care, case-based learning

Introduction

Total health care costs in the United States are much higher than those in almost all other developed countries.1 At the turn of this century, national health expenditures exceeded US$1.3 trillion and were 13.8% of gross domestic product (GDP)2; and 10 years later, the expenditures had increased to US$3.2 trillion and 17.8% of GDP.3 By 2026, it is projected that national health spending will reach US$5.7 trillion and represent 19.7% of GDP.3

Many factors have been implicated as contributors to these rising costs, including an inadequate understanding of health care costs on the part of care providers,4,5 a lack of knowledge or attention to available guidelines by physicians,6 as well as reluctance on the part of physicians to discuss medical costs with patients.7 Currently, the lack of physician knowledge of how to provide better care at a lower cost remains a significant barrier.8 Physicians also suffer from a lack of knowledge of guidelines designed to drive value-based care.6 Efforts are underway to improve knowledge and competency. The American College of Physicians has developed a high-value care curriculum that has been adopted by some internal medicine programs and is being used to educate physicians and residents on appropriate use of limited health care resources.9 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires training programs to graduate residents competent in cost-effective practice and proper resource allocation as part of the systems-based practice core competency.10

It has been suggested that value-based care should be integrated into existing medical school curricula8 and that future efforts to incorporate costs of care into curricula explore opportunities to emphasize experiential learning.11 Medical school curricula typically have little to no extra time to devote to new topics. Several programs have introduced medical students to cost of care issues through isolated pilot projects within traditional curricular pedagogies.12 Based on previous successful integration of diverse subjects into problem-based learning (PBL), Gray and Lorgelly13 proposed incorporation of health economics into a PBL program. A review of health economics in undergraduate medical education (UME) curricula at 3 medical schools in the United Kingdom found that some schools incorporated health economics learning objectives into PBL sessions.13 Their results suggest that students’ satisfaction with health economics topics was higher when incorporated as part of PBL pedagogy as compared with more traditional approaches. Building on these pilot results, we studied 2 questions: Does the introduction of health care cost topics as a required part of a PBL/case-based learning (CBL) program for all students result in (1) engagement of students in conversations about health care cost topics and (2) an increase in student-initiated discussions about health care cost topics over time?

Methodology

Existing ZSOM curriculum

This study took place during academic years 2014-2016, included 1 cohort of 98 medical students at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell (ZSOM), and was incorporated into ZSOM’s existing curriculum. The first 2 years of ZSOM’s curriculum consisted of 6 integrated, sequential courses (Courses 1-6). Each student was assigned to a small, peer group with 1 faculty facilitator for the duration of a course (Table 1) to learn basic and clinical sciences in a PBL/CBL program called PEARLS (Patient-Centered Explorations in Active Reasoning, Learning and Synthesis).14 PEARLS cases prompted students to develop biomedical, clinical, and social science learning objectives, which were explored in small group discussions as well as in complementary sessions, including large groups, labs, and multidisciplinary-practice-based clinical experiences.

Table 1.

Programmatic demographics.

| Class of 2018 | Number of PEARLS groups | Range of students per group | Facilitator qualifications | Number of PEARLS case conference sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course 1 | 12 | 8-9 | MD: 7 DO: 0 PhD: 6 |

10 |

| Course 2 | 12 | 8-9 | MD: 5 DO: 3 PhD: 4 |

18 |

| Course 3 | 12 | 8-9 | MD: 7 DO: 1 PhD: 4 |

19 |

| Course 4 | 12 | 8-9 | MD: 4 DO: 4 PhD: 4 |

19 |

| Course 5 | 12 | 8-9 | MD: 4 DO: 2 PhD: 6 |

24 |

| Course 6 | 11a | 8-9 | MD: 3 DO: 3 PhD: 5 |

20 |

Abbreviation: PEARLS, Patient-Centered Explorations in Active Reasoning, Learning and Synthesis.

There were 11 groups in Course 6 due to an unexpected loss of a facilitator.

Students typically participated in PEARLS for three 2-hour sessions per week. The first PEARLS session of each week was dedicated to students dissecting 2 cases and developing specific learning objectives for each case. Following this session, students independently researched all learning objectives, using resources they individually identified. During the second and third PEARLS sessions of each week, students reconvened in their small groups for case conferences to discuss and synthesize their understanding of the material for each of the 2 cases. Student peer groups changed for each course. PEARLS faculty facilitators monitored the case conferences and responded to process only and did not contribute to content discussion.

Initiation of Health Care Costs Research Study

In August of the 2014-2015 academic year, the Health Care Costs Research Study was initiated with first year medical students. During Course 1, there was no explicit expectation for students to discuss health care cost topics as part of PEARLS. During the beginning of Course 2, a large group meeting was held with all first year medical students, PEARLS facilitators, and the Director of the PEARLS program. Students were instructed to identify, research, and incorporate health care cost topics into future PEARLS case conferences when appropriate, for the remainder of the year. Definitions of health care cost topics were shared, as were examples of learning objectives related to health care cost topics that could have been derived from prior PEARLS cases. Students were introduced to some potential resources for their health care cost topics research. Some examples of health care cost topics provided included direct costs of care (eg, costs of medications, diagnostic tests, procedures) as well as topics related to health economics (eg, variations in cost of care, health care expenditures, insurance coverage).

Students were told that faculty facilitators would track each student’s participation in discussions related to health care cost topics as well as each student’s initiation of new discussions of health care cost topics during subsequent PEARLS case conferences. During the beginning of Course 5, another large group meeting was held with all the now second year medical students, their PEARLS facilitators, and the Director of the PEARLS program to remind them to continue addressing health care cost topics as part of PEARLS throughout Courses 5 and 6 as they had done during the prior year.

As an example, Course 6, entitled “The Human Condition,” provides an integrated presentation of the structure and function of the neuroaxis, introducing students to core concepts in neurology and psychiatry. Each week of the course is designed with its own theme, during which all the learning sessions, including PEARLS, address topics relating to the weekly theme. During Week 8 of the course, which examines subcortical structure and function of the brain, students researched 2 PEARLS cases: Parkinson disease and cerebellar function. Included as part of each of these cases were references to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of movement disorders. For each case, students identified and researched health care cost topics related to each case, analogous to the way they do for biomedical content areas. Students then discussed their findings with one another as part of their overall case discussion with their PEARLS groups during the subsequent group meeting.

Assessment of health care cost discussions

PEARLS faculty facilitators were instructed during faculty development meetings prior to each course, beginning with Course 1, throughout the 2014-2016 academic years to record freeform, on paper, whether a student engaged in discussions related to health care cost topics during PEARLS case conferences. Engagement included both participation as well as initiation of discussions of health care cost topics. “Participated” was attributed to a student who participated in case conference discussions about a health care cost topic initiated by another student. “Initiated” was attributed to a student who began a case conference discussion about a health care cost topic. In addition, facilitators were encouraged to record narrative comments excerpted from these discussions.

At the end of each course, facilitators completed a Faculty Assessment of Students form used for grading (pass/fail) student performance during PEARLS. During the 2-year study period, a closed-ended question asking if students initiated or participated in a discussion of health care costs in PEARLS case conferences during the course was added to the Faculty Assessment of Students form. This question was included for all courses (Courses 1-6) with Course 1 being used as a baseline measurement of health care cost topic discussions prior to the introduction of the Health Care Costs Research Study to students during Course 2, after which time the question was included in calculating the PEARLS student performance grade.

Statistical analysis

Faculty assessment of the medical students for each course indicated whether the student initiated, only participated, or did not participate in discussion of health care cost topics during the case conferences. Faculty assessments were summarized as frequencies and percentages within each course. The Friedman test was used because the same students were evaluated on the 3-point scale (did not participate, participated, and initiated) at the end of each course (non-independent samples). The Friedman test results were followed by paired comparisons of courses using the Wilcoxon signed rank test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple paired comparisons resulting in a cut-off of P < .003 being used to determine statistical significance. Chi-square tests for association were used to compare cohorts on the 3-point scale. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Windows Version 26; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

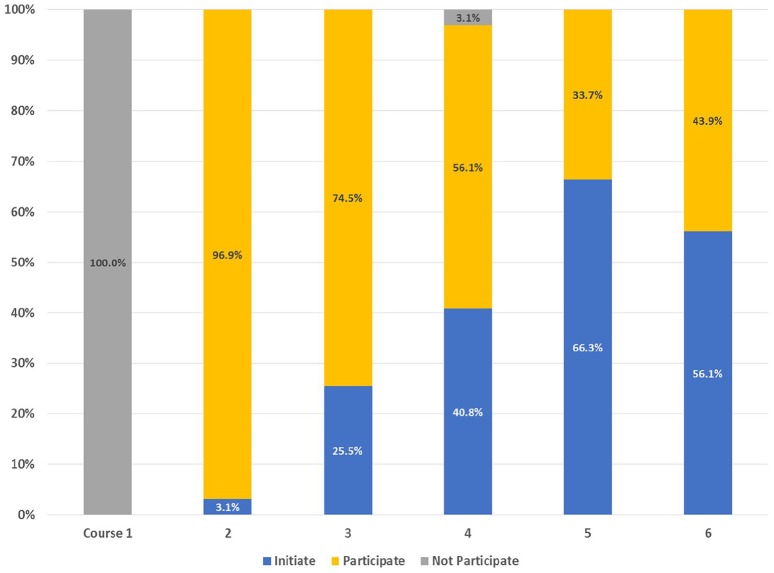

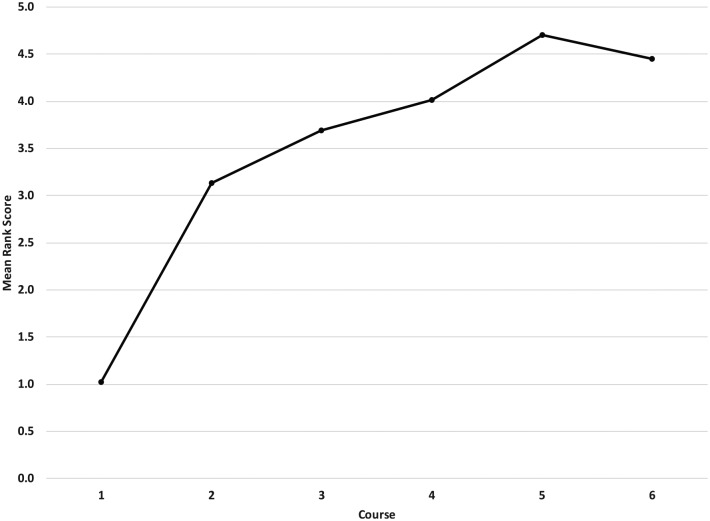

Figure 1 displays results of the medical students’ engagement in discussions of health care cost topics. The level of engagement is categorized into participation or initiation. A Friedman test was applied to determine if the medical students’ level of engagement changed throughout the research project, from Course 1 through Course 6. Course 1 was considered a baseline as the students had not been specifically instructed to include consideration of health care cost topics until Course 2. There was a significant change in engagement in discussions about health care cost topics, χ2(5) = 326.5, P < .001. A post hoc analysis with Wilcoxon signed rank test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction applied, resulting in a significance level set at P < .003. The nature of medical students’ engagement in discussing health care cost topics also changed throughout the course sequence. In Course 3, a greater percentage of students initiated discussions of health care cost topics (25.5%) than in Course 2 (3.1%) (Z = –4.1, P < .001). In Course 4, 40.8% initiated discussion (Z = –1.73, P = .083) with 3 students not participating in any health care cost discussions, and in Course 5, with all students again engaged, 66.3% initiated discussions (Z = –3.9, P < .001). Although a lower percentage of students initiated discussions during Course 6 than the previous course (56.1%), it was not a meaningful decrease (Z = 1.58, P = .114). A greater percentage of students initiated discussions of health care cost topics throughout the study, going from a low of 3% in Course 2 to a high of more than 66% in Course 5 (Z = –7.75, P < .001). Mean ranks from the Friedman test for Courses 1 to 6 were 1.02, 3.13, 3.69, 4.01, 4.70, and 4.45, respectively. A Pearson regression found that medical students increasingly initiated health care cost topic discussions in the sequence of courses (R2 = 0.887, P < .01; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Categorization of medical students’ level of engagement in discussion of health care cost topics by course. “Not Participate” indicates the percent of students who did not participate in case conference discussions about health care cost topics initiated by another student; “Participate,” the percent of students who participated in case conference discussions about health care cost topics initiated by another student but did not initiate any new case conference discussions related to health care cost topics; and “Initiate” represents the percent of students who initiated case conference discussions about health care cost topics.

Figure 2.

Mean rank scores of medical students’ level of engagement in health care cost discussions by course. Level of engagement categorization is as follows: did not participate = 1; participated = 2; initiated = 3.

Discussion

Medical students in this study responded positively when prompted to incorporate health care cost topics into their PBL/CBL discussions (PEARLS) throughout the first 2 years of medical school. During the first course of first year of medical school, students did not naturally include conversations about health care cost topics during their PEARLS discussions. Subsequently, when asked to discuss health care cost topics, all the students in our program engaged in these conversations, either through participating in discussions raised by one of their peers or by initiating a new discussion related to the patients in their PEARLS cases throughout the subsequent 2 years (except during Course 4 when we had 3 students who did not participate or initiate any discussions on health care cost topics). In addition, more students initiated new discussions of health care cost topics as part of their case conferences over time (Figure 1). Some examples of health care cost topics related to their PEARLS cases that were raised and discussed by the students in various courses include direct and indirect costs of treating schizophrenia in the United States, the costs of medications available to treat Hepatitis C, the relationship between utilization and physician law suits, the cost of supporting adequate nutrition programs in developing countries, the cost of treatment for leukemia, and patient assistance programs to support high-cost medications. For the example week from Course 6, which examined subcortical structure and function of the brain, students in different PEARLS groups discussed the annual cost of treating Parkinson disease in the United States, the cost of drug and deep brain stimulation therapy, the yearly societal costs of treating Parkinson disease, and the cost of drugs for these patients as related to potential “donut holes” in their benefits.

From Course 1 through Course 5, a higher number of students initiated new conversations related to health care cost topics with each successive course. This finding is important because it mirrors the behavior desired from trainees and physicians during clinical care—moving beyond participating in conversations about health care cost topics when they are raised by others and initiating the conversations about relevant health care cost topics with patients and other providers caring for a patient.7 Initiating discussions about health care cost topics in the context of patient care is an important leadership quality desired from physicians.9,10 Of note, Course 6 did not demonstrate a statistically significant increase in students’ initiation of health care cost topics as compared with Course 5, which suggests that the study intervention had reached its maximum effect and that other techniques should be used to further advance engagement. However, it is important to note that 100% of the students were still engaged in conversations about health care cost topics during the 2 second year courses.

The findings from this study are an important step in raising awareness of and knowledge about health care costs among future physicians and getting them accustomed to considering these topics in the context of discussing patient cases. Previous work has shown that exposure to standardized practices aids in the development of durable practice patterns15 and we hope these experiences will lay the groundwork that primes students to be ready to discuss health care cost topics with patients as well as other providers. The potential impact of this intervention is that students will be more knowledgeable about, and more likely to discuss, health care costs as part of inpatient as well as outpatient care with health care teams, patients, and providers. Whether these behaviors are transferable to other learning and care delivery environments, such as clinical rotations, will require further study. Whether or not these students will be more sensitive to the impact of health care costs in their decision making as clinicians, and ultimately become intrinsically motivated to do so, will also require much further study. The students in this study were told that they would be observed and graded on their participation in discussions of health care costs, which was likely a source of motivation for doing so.

Incorporating health care cost topics into a PBL/CBL program has the advantages of being a time-efficient option and an engaging pedagogy that students enjoy. The small group nature of the program allows students to learn from their colleagues’ personal experiences, which may include knowledge of relevant fields such as finance and health care consulting. Two major challenges with using a PBL/CBL program for this content include the opportunity cost of lost time to discuss the basic, clinical and other social science topics as well as the lack of well-established resources for students to use to research this information. The latter may result in students bringing less reliable or conflicting information to group discussions which may engender frustration and/or confusion.

Our study has several limitations. Students have a finite amount of curricular and self-directed learning time during the first 2 years of medical school. Incorporation of health care cost topics into our PBL/CBL program may take away time from students’ focus on other topics addressed during PEARLS such as biomedical science content and other forms of clinical decision making, and individual students may prioritize these topics differently—this issue should be examined in future research. The facilitators did not go through inter-rater reliability training for health care costs. Although to some extent this was mitigated through discussions at facilitator meetings about whether a topic was related to health care costs and consensus was reached, it is something we will strive for in future work. Finally, we did not examine how students applied health care cost information beyond their PEARLS case conferences and most importantly if they applied cost considerations in their patient care settings. In the future, we will explore both these questions.

Conclusions

Health care reform is focused on managing the growth of health care expenditures and improving the value of health care decision making. Physicians have some responsibility to value-based health care. We have shown that medical students in a PBL/CBL program can identify, participate in, and initiate discussions of health care cost topics based on patient cases without adding curricular time. Furthermore, we found that, over time, more students will initiate new conversations about health care cost topics related to their patient-based PBL/CBL cases. This study demonstrated that the incorporation of health care cost topics into a PBL/CBL program is feasible and well received by students. Going forward, we will follow students who have participated in the Health Care Costs Research Project to determine if their presence on resident-led inpatient teams has any impact on raising awareness of health care costs during rounds, which has the potential to directly impact and lower the cost of patient care and would be the most important outcome of this intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Krista L Paxton and Saori Wendy Herman, MLIS, AHIP, for their assistance with preparation of the manuscript as well as Lauren Block, MD, and Jeffrey Bird, MA, for their assistance thinking about measurement of future outcomes. They would also like to acknowledge Joanne M Willey, PhD, for her critical comments on the manuscript as well as the contributions of the students, faculty and staff at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell who made the work described here possible.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Categorization of medical students’ level of engagement in discussion of health care cost topics by course.

| Health care cost discussion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course | N | Not participate (%) | Participate (%) | Initiate (%) | Total (%) |

| 1 | 98 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 2 | 98 | 0.0 | 96.9 | 3.1a | 100.0 |

| 3 | 98 | 0.0 | 74.5 | 25.5a,b | 100.0 |

| 4 | 98 | 3.1 | 56.1 | 40.8a,b | 100.0 |

| 5 | 98 | 0.0 | 33.7 | 66.3a,b,c,d | 100.0 |

| 6 | 98 | 0.0 | 43.9 | 56.1a,b,c | 100.0 |

Significantly different than Course 1.

Significantly different than Course 2.

Significantly different than Course 3.

Significantly different than Course 4.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: SBG conceived of the study, was the Director of the PEARLS program during the study, and is the primary author of the manuscript. JS assisted with editing the manuscript, organizing the components, and preparing it for submission. SD and DEE were responsible for training the facilitators and oversight of data collection during the study period. RL assisted with data collection and organization. JEH conceived of the statistical analysis, performed all the analyses, wrote the results, and prepared the figures for the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of Data and Material: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval: This study was submitted to the University’s Institutional Review Board and was determined to be exempt from review.

Informed Consent: All data utilized for this study came from students who gave their consent to have their answers used after reading and agreeing to the following statement: “I voluntarily consent to participate in the Research Registry and therefore give permission for the educational data that has been or will be collected throughout my undergraduate experience at Zucker School of Medicine to be included in the Registry.”

ORCID iD: Samara B Ginzburg  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0466-0316

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0466-0316

References

- 1. Miller Center, University of Virginia. Cracking the Code on Health Care Costs: A Report by the State Health Care Cost Containment Commission. Charlottesville, VA: Miller Center, University of Virginia; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Catlin A, Cowan C, Heffler S, Washington B. National health spending in 2005: the slowdown continues. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:142-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cuckler GA, Sisko AM, Poisal JA, et al. National health expenditure projections, 2017-26: despite uncertainty, fundamentals primarily drive spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:482-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Varkey P, Murad MH, Braun C, Grall KJ, Saoji V. A review of cost-effectiveness, cost-containment and economics curricula in graduate medical education. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:1055-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Korn LM, Reichert S, Simon T, Halm EA. Improving physicians’ knowledge of the costs of common medications and willingness to consider costs when prescribing. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:31-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinberger SE. Educating trainees about appropriate and cost-conscious diagnostic testing. Acad Med. 2011;86:1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ubel PA, Zhang CJ, Hesson A, et al. Study of physician and patient communication identifies missed opportunities to help reduce patients’ out-of-pocket spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:654-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levy AE, Shah NT, Moriates C, Arora VM. Fostering value in clinical practice among future physicians: time to consider COST. Acad Med. 2014;89:1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American College of Physicians. Newly revised: curriculum for educators and residents (version 4.0). https://www.acponline.org/clinical-information/high-value-care/medical-educators-resources/curriculum-for-educators-and-residents. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- 10. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Manual). Chicago, IL: Accredi-tation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2007. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gonzalo JD, Dekhtyar M, Starr SR, et al. Health systems science curricula in undergraduate medical education: identifying and defining a potential curricular framework. Acad Med. 2017;92:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gould BE, O’Connell MT, Russell MT, Pipas CF, McCurdy FA. Teaching quality measurement and improvement, cost-effectiveness, and patient satisfaction in undergraduate medical education: the UME-21 experience. Fam Med. 2004;36:S57-S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gray E, Lorgelly PK. Health economics education in undergraduate medical degrees: an assessment of curricula content and student knowledge. Med Teach. 2010;32:392-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ginzburg SB, Deutsch S, Bellissimo J, Elkowitz DE, Stern JN, Lucito R. Integration of leadership training into a problem/case-based learning program for first- and second-year medical students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:221-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sellers MM, Keele LJ, Sharoky CE, Wirtalla C, Bailey EA, Kelz RR. Association of surgical practice patterns and clinical outcomes with surgeon training in university- or non-university-based residency program. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:418-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]