Abstract

Background

Enrichment strategies improve therapeutic targeting and trial efficiency, but enrichment factors for sepsis trials are lacking. We determined whether concentrations of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (sTNFR1), interleukin-8 (IL8), and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2) could identify sepsis patients at higher mortality risk and serve as prognostic enrichment factors.

Methods

In a multicenter prospective cohort study of 400 critically ill septic patients, we derived and validated thresholds for each marker and expressed prognostic enrichment using risk differences (RD) of 30-day mortality as predictive values. We then used decision curve analysis to simulate the prognostic enrichment of each marker and compare different prognostic enrichment strategies.

Measurements and main results

An admission sTNFR1 concentration > 8861 pg/ml identified patients with increased mortality in both the derivation (RD 21.6%) and validation (RD 17.8%) populations. Among immunocompetent patients, an IL8 concentration > 94 pg/ml identified patients with increased mortality in both the derivation (RD 17.7%) and validation (RD 27.0%) populations. An Ang2 level > 9761 pg/ml identified patients at 21.3% and 12.3% increased risk of mortality in the derivation and validation populations, respectively. Using sTNFR1 or IL8 to select high-risk patients improved clinical trial power and efficiency compared to selecting patients with septic shock. Ang2 did not outperform septic shock as an enrichment factor.

Conclusions

Thresholds for sTNFR1 and IL8 consistently identified sepsis patients with higher mortality risk and may have utility for prognostic enrichment in sepsis trials.

Keywords: Sepsis, Tumor necrosis factor receptors, Interleukin-8, Angiopoietin-2, Biomarkers, Prognostic enrichment

Introduction

Sepsis carries a high mortality and has limited pharmacologic therapy [1]. A pipeline of therapies targeting inflammation, vascular regulation, and immune regulation are in development, often in tandem with the oncology, autoimmune, and cardiovascular spheres [2, 3]. However, these therapies may be associated with adverse effects that tip the risk-benefit scale in favor of testing the new therapy among high-risk patients first, to avoid exposing low-risk patients to a potentially risky therapy. In addition, prior sepsis trials have been hampered by imprecise estimates of baseline mortality [4], making interpretation challenging due to inadequate power.

Several fields have embraced enrichment strategies to refine patient selection for clinical trials, fostering the translation of experimental therapies [5–8]. This includes “prognostic enrichment,” selecting patients with a greater likelihood of having an outcome, and “predictive enrichment,” selecting patients with a greater likelihood of responding to a specific intervention [9–11]. Despite broad appeal, enrichment strategies have not been widely applied in critical care, partly due to a dearth of biomarkers that might serve as enrichment factors [12–15].

We sought to develop a simple biomarker-based prognostic enrichment method for selecting high-risk patients for future sepsis trials. We chose three markers, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (sTNFR1), interleukin-8 (IL8), and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2), which are easily measurable, associate with sepsis outcomes, and represent pathways that are potential targets for sepsis therapy [16–22].

To assess each marker’s prognostic enrichment potential, we derived concentration thresholds and validated whether the thresholds consistently identified subjects at higher mortality risk in two separate cohorts using risk differences as predictive values. Additionally, we used decision curve analysis to illustrate the potential benefits of using each marker to select subjects for clinical trials.

Methods

Study design

Detailed methods are provided in the supplement (Additional file 1). We performed a multicenter prospective cohort study enrolling critically ill septic patients admitted from the emergency departments at the University of Pennsylvania (PENN) and the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). Both cohorts have been described previously [23, 24]. We chose a priori to enroll 200 subjects at each site during the same period. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. We defined immunocompromise using Acute Physiology, Age, Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) criteria and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) using Berlin criteria [25–27]. We defined septic shock as the receipt of vasopressors and a lactate > 2 mmol/l on the day of intensive care unit (ICU) admission [1]. Each cohort was approved by its institution’s Institutional Review Board.

Plasma protein measurement

Plasma was obtained as close to ICU bed request as feasible and within 24 h of ICU admission. We measured sTNFR1, IL8, and Ang2 concentrations using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (R&D Systems).

Statistical methods

We first confirmed each marker’s prognostic value by determining whether the marker was independently associated with mortality and whether the marker improved model fit (likelihood-ratio test) and discrimination (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC]) when added to a clinical variable model for mortality. We chose variables that were easily available at admission and associated with mortality, including age, diabetes, cirrhosis, immunocompromise, septic shock, and mechanical ventilation. To operationalize each marker, we split the population by enrollment site and derived thresholds for each marker in the derivation population (PENN) using the Youden method [28]. We performed logistic regression adjusting for the variables above and calculated standardized risks and risk differences (RD) for mortality between marker-positive and marker-negative subjects [29]. For validation, we simulated the effect of simply applying each marker threshold in the validation population (UCSF) without clinical variables and focused on whether the unadjusted RD fell within the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the standardized RD in the derivation population, indicating the marker identified high-risk patients in a similar fashion while accounting for differences in baseline mortality [30]. We secondarily performed adjusted analyses in the validation population and tested whether each marker threshold improved model fit and discrimination when added to a clinical variable model for mortality in each population. We tested for effect modification by immunocompromised status because differences in inflammatory pathways have been reported in these patients [24].

Next, we employed decision curve analysis (DCA) to illustrate each marker’s potential as an enrichment factor (i.e., enroll if marker-positive) [31–33]. The net benefit (percent true positives − percent false positives) was calculated across a range of threshold probabilities for mortality, where the threshold probability represents the mortality risk a trial would set for enrollment (i.e., enroll patients with ≥ 35% mortality risk). Decision curves are interpreted vertically; at each threshold probability, the strategy with the highest net benefit identifies the highest number of true positives relative to false positives and thus selects the most efficient trial population. We compared five enrichment strategies: (1) enrolling all sepsis patients (no enrichment), (2) enrolling septic shock patients, (3) enrolling patients positive for a single marker, (4) enrolling patients positive for two markers, and (5) enrolling patients whose predicted mortality using the markers as continuous variables met a certain threshold [22]. To further illustrate enrichment potential, we calculated sample sizes for a hypothetical trial testing a therapy with a 20% relative risk reduction of mortality, assuming 90% power. We chose septic shock as our primary clinical variable enrichment factor because it is often used to define a high-risk subgroup in sepsis trials [34, 35]. Secondarily, we evaluated an APACHE II score ≥ 20 and a peak lactate ≥ 4 mmol/l within the first 24 h as clinical variable prognostic enrichment factors [26, 36].

Analyses were performed using Stata 15.1; a two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

We enrolled 400 critically ill septic patients (Additional file 2: Figure S1); baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The derivation population was younger, more immunocompromised, had less septic shock, more African-American subjects, and fewer Asian subjects. Both populations had significant 30-day mortality, 41.0% and 27.0% in the derivation and validation populations, respectively. Plasma concentrations of sTNFR1 and IL8 were higher in the derivation population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population in the derivation and validation cohorts

| Variable | Derivation (n = 200) | Validation (n = 200) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60 (49.5–69) | 67 (59–78) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 110 (55.0%) | 105 (52.5%) | 0.62 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 110 (55.0%) | 106 (53%) | < 0.001 |

| African American | 82 (41.0%) | 24 (12.0%) | |

| Asian | 4 (2.0%) | 50 (25.0%) | |

| Other | 4 (2.0%) | 20 (10.0%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 59 (29.5%) | 57 (28.5%) | 0.83 |

| Cirrhosis | 20 (10.0%) | 17 (8.5%) | 0.61 |

| Immunocompromised | 95 (47.5%) | 27 (13.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 78 (39.0%) | 104 (52.5%) | 0.007 |

| APACHE II | 25 (19.5–32.5) | 25 (19–33) | 0.99 |

| Septic shock at presentation | 77 (38.5%) | 98 (49.0%) | 0.034 |

| Invasive ventilation at presentation | 82 (41.0%) | 82 (41.0%) | 1.0 |

| ARDS | 57 (28.5%) | 50 (25.3%) | 0.47 |

| 30-day mortality | 82 (41.0%) | 54 (27.0%) | 0.003 |

| sTNFR1 (pg/ml) | 8444 (4332–13,450) | 6366 (3232–11,024) | 0.004 |

| IL8 (pg/ml) | 115.7 (51.2–325.6) | 54.7 (23.5–241.0) | < 0.001 |

| Ang2 (pg/ml) | 13,933 (8747–26,865) | 13,894 (7146–24,447) | 0.24 |

Abbreviations: APACHE Acute Physiology, Age and Chronic Health Evaluation, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, sTNFR1 soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1, IL interleukin, Ang2 angiopoietin-2

Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1

The plasma sTNFR1 concentration at ICU admission independently associated with mortality (OR [95% CI] per 1-log increase 1.68 [1.23–2.28]; p = 0.001), and adding the sTNFR1 concentration to a clinical variable model for mortality improved model fit and marginally improved discrimination (Additional file 2: Table S1). The optimal sTNFR1 threshold in the derivation population was 8861 pg/ml; 46.5% of patients were sTNFR1-positive with a 21.6% (95% CI 8.1–35.2; p = 0.002) adjusted increased absolute risk of mortality. In the validation population, 33.5% were sTNFR1-positive with a 17.8% (95% CI 4.2–31.3; p = 0.010) unadjusted increased absolute risk of mortality, which was within the 95% CI of the RD in the derivation population (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, the RD in the validation population was 13.0% (95% CI 0.3–25.7; p = 0.045). The sTNFR1 threshold improved model fit and marginally improved discrimination when added to a clinical variable model for mortality in each population (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 2.

Risks and risk differences of 30-day mortality categorized by marker positivity for soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (sTNFR1), interleukin-8 (IL8), and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2), in the derivation (N = 200) and validation (N = 200) cohorts. Standardized risks and risk differences are reported for the derivation cohort, adjusted for age, cirrhosis, immunocompromised state, septic shock at presentation, and mechanical ventilation at presentation. Crude risks and risk differences are reported for the validation cohort. The IL8 analysis is limited to immunocompetent patients (N = 105 in derivation cohort, N = 173 in validation cohort)

| Marker and site | Number (%) of subjects above threshold | 30-day mortality (95% CI) if below threshold | 30-day mortality (95% CI) if above threshold | Risk difference of 30-day mortality (95% CI) if above threshold | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sTNFR1 > 8861 pg/ml | |||||

| Derivation | 93 (46.5%) | 30.4% (21.6, 39.2) | 52.0% (42.3, 61.7) | 21.6% (8.1, 35.2) | 0.002 |

| Validation | 67 (33.5%) | 21.1% (14.1, 28.0) | 38.8% (27.1, 50.5) | 17.8% (4.2, 31.3) | 0.010 |

| IL8 > 94 pg/ml | |||||

| Derivation | 57 (54.3%) | 23.2% (11.8, 34.6) | 40.9% (29.8, 52.0) | 17.7% (1.6, 33.8) | 0.031 |

| Validation | 68 (39.3%) | 18.9% (11.9, 25.8) | 44.1% (32.3, 55.9) | 27.0% (13.2, 40.8) | < 0.001 |

| Ang2 > 9761 pg/ml | |||||

| Derivation | 139 (69.5%) | 25.8% (14.6, 37.1) | 47.1% (39.3, 54.9) | 21.3% (7.3, 35.3) | 0.003 |

| Validation | 127 (63.5%) | 19.2% (10.2, 28.2) | 31.5% (23.4, 39.6) | 12.3% (0.2, 24.4) | 0.046 |

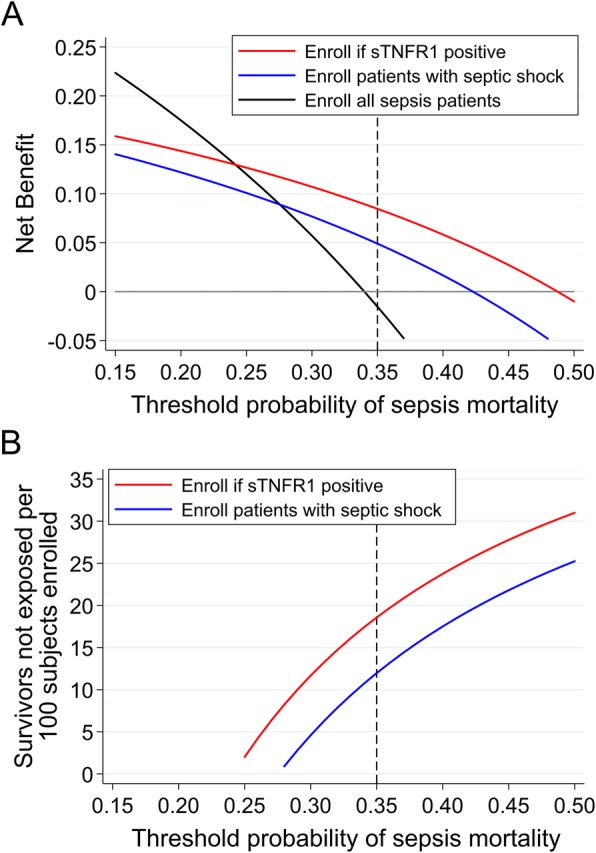

For prognostic enrichment, enrolling sTNFR1-positive patients was superior to enrolling patients with septic shock based on test characteristics (positive predictive value [PPV] 48.8% vs. 42.3%; negative predictive value [NPV] 75.8% vs. 72.4%; Additional file 2: Table S3) and DCA. As shown in Fig. 1a, if a trial sought to enroll patients with < 25% mortality risk, enrolling all sepsis patients was optimal and no enrichment was needed. However, if a trial sought patients at higher mortality risk, i.e., ≥ 35%, enrolling sTNFR1-positive patients was superior to enrolling septic shock patients or enrolling all sepsis patients. In terms of efficiency, if a trial sought to enroll patients with ≥ 35% mortality risk, enrolling sTNFR1-positive patients would result in a strategy equivalent to 18 fewer survivors exposed per 100 patients enrolled, whereas enrolling septic shock patients would result in 12 fewer survivors exposed, compared to enrolling all sepsis patients (Fig. 1b, Additional file 2: Table S5). In terms of statistical power for a trial testing a therapy with a 20% relative risk reduction of mortality, enrolling sTNFR1-positive patients would reduce the required sample size by 43.3% (N = 1126), whereas enrolling septic shock patients would reduce it by 28.1% (N = 1428), compared to enrolling all sepsis patients (N = 1986).

Fig. 1.

a Net benefit curves of three clinical trial enrollment strategies: enrolling all sepsis patients (black line), enrolling patients with septic shock (blue line), and enrolling sTNFR1 positive patients (red line). The x-axis represents the threshold probability, which is the probability of mortality that a hypothetical trial would require for enrollment. The y-axis is the net benefit, which represents the tradeoff between true positives and false positives, and is calculated as (true positives/n) − (false positive/n) × (pt/1 − pt), where pt is the threshold probability. The net benefit varies with the threshold probability since it reflects the relative harms of missing non-survivors (false negatives) and enrolling too many survivors (false positives). We focused on threshold probabilities between 15 and 50%, because enrichment is unnecessary at low thresholds given baseline mortality, and we reasoned that patients with > 50% mortality risk may be excluded from trials because they may be less likely to respond to therapy. Net benefit curves are interpreted vertically; at each threshold probability, the strategy with the highest net benefit is the optimal strategy for enriching a trial with high-risk subjects. For example, if a trial sought to enroll patients with at least 35% mortality risk (dotted vertical line), enrolling only sTNFR1-positive patients is the optimal strategy. b Intervention curves comparing enrolling all sepsis patients (reference, not shown), enrolling patients with septic shock (blue line), and enrolling sTNFR1 positive patients (red line). Intervention curves are an alternative representation of net benefit and are also interpreted vertically. The y-axis represents the number of survivors that avoid the intervention, which in this case is enrollment and exposure to unproven therapy. At a threshold probability of 35%, enrolling sTNFR1-positive patients would lead to a greater reduction in the number of survivors unnecessarily exposed compared to enrolling patients with septic shock

Interluekin-8

The plasma IL8 concentration at ICU admission independently associated with mortality (OR [95% CI] per 1-log increase 1.25 [1.09–1.43]; p = 0.001) and improved model fit and marginally improved discrimination when added to a clinical variable model for mortality (Additional file 2: Table S1). The optimal IL8 threshold was 94 pg/ml. We found effect modification by immunocompromised status on the IL8-mortality association (p = 0.033), with the association driven by immunocompetent patients (Additional file 2: Table S6). In the derivation population, 54.3% of immunocompetent patients were IL8-positive with a 17.7% (95% CI 1.6–33.8; p = 0.031) adjusted increased absolute risk of mortality. In the validation population, 39.3% of immunocompetent subjects were IL8-positive with a 27.0% (95% CI 13.2–40.8; p < 0.001) unadjusted absolute increased risk of mortality, which was within the 95% CI of the RD in the derivation population (Table 2). When adjusted for clinical variables, the RD in the validation population was 22.1% (95% CI 7.4–36.8; p = 0.003). The IL8 threshold improved model fit and marginally improved discrimination when added to a clinical variable model for mortality in each population (Additional file 2: Table S2).

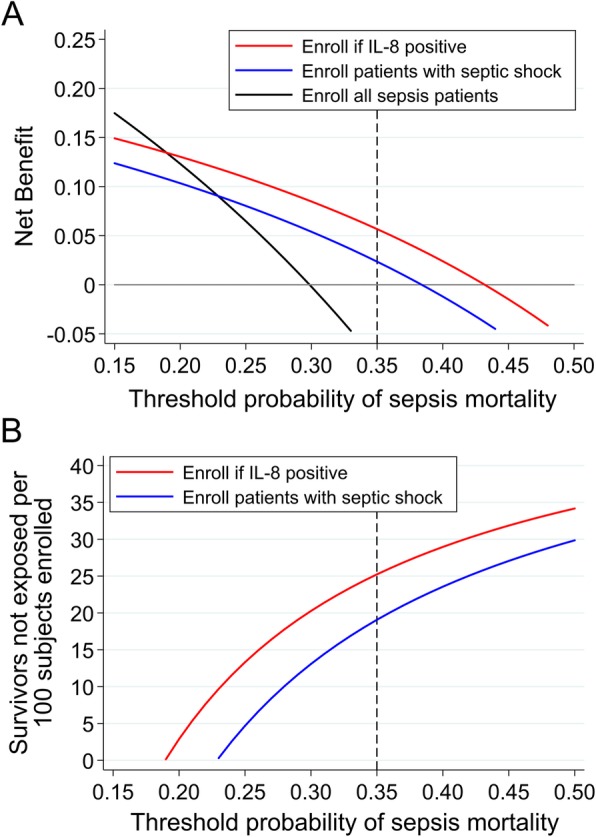

Among immunocompetent patients, the IL8 threshold was the superior prognostic enrichment factor compared to septic shock based on test characteristics (PPV 43.2% vs. 38.4%; NPV 81.7% vs. 77.1%; Additional file 2: Table S4) and DCA. As shown in Fig. 2a, if a trial sought to enroll patients with < 20% mortality risk, enrolling all sepsis patients was optimal; however, if a trial sought patients at higher mortality risk, i.e., ≥ 35%, enrolling IL8-positive patients was optimal. For example, if a trial sought to enroll patients with ≥ 35% mortality risk, enrolling IL8-positive patients would result in a strategy equivalent to 25 fewer survivors exposed per 100 patients enrolled, whereas enrolling septic shock patients would result in 19 fewer survivors exposed, compared to enrolling all sepsis patients (Fig. 2b, Additional file 2: Table S7). In terms of statistical power, enrolling IL8-positive patients would reduce the required sample size by 41.8% (N = 1380), whereas enrolling septic shock patients would reduce it by 30.0% (N = 1660), compared to enrolling all sepsis patients (N = 2372).

Fig. 2.

a Net benefit curves of three clinical trial enrollment strategies, enrolling all sepsis patients (black line), enrolling patients with septic shock (blue line), and enrolling IL-8-positive patients (red line), in a population restricted to immunocompetent patients. The x-axis represents the threshold probability, which is the probability of sepsis mortality that a hypothetical trial would require for enrollment. The y-axis is the net benefit, which represents the tradeoff between true positives and false positives, and is described further in the legend of Fig. 1. The net benefit curves are interpreted vertically, such that at each threshold probability, the strategy with the highest net benefit is the optimal strategy for enriching a trial with high-risk subjects. For example, if a trial sought to enroll patients with at least 35% mortality risk (dotted vertical line), enrolling only IL-8 positive patients is the optimal strategy. b Intervention curves comparing enrolling all sepsis patients (reference, not shown), enrolling patients with septic shock (blue line), and enrolling IL-8-positive patients (red line), in a population restricted to immunocompetent patients. The y-axis represents the number of survivors that avoid the intervention, which in this case is enrollment and exposure to unproven therapy. Intervention curves are also interpreted vertically. For example, at a threshold probability of 35%, enrolling only IL-8-positive patients would lead to a greater reduction in the number of survivors unnecessarily exposed compared to enrolling patients with septic shock

Angiopoietin-2

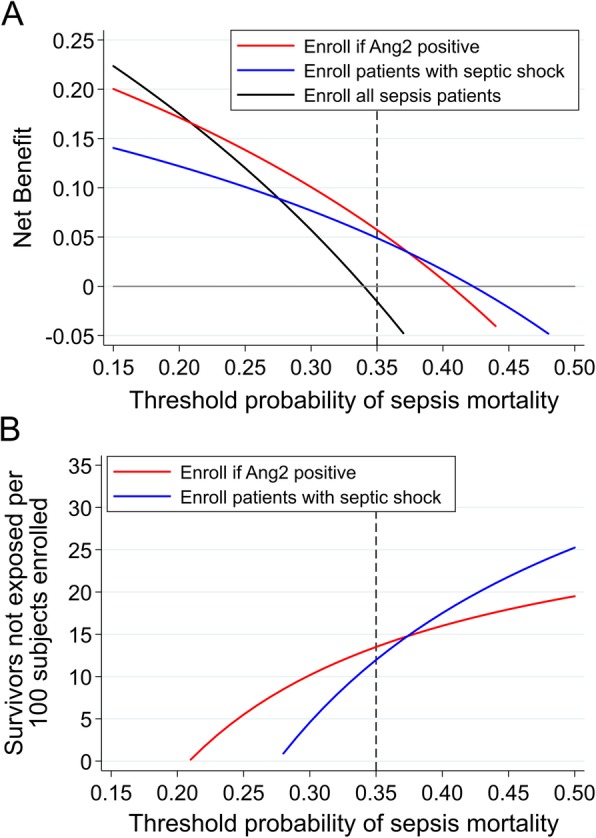

The plasma Ang2 concentration at ICU admission independently associated with mortality (OR [95% CI] per 1-log increase 1.53 [1.16–2.01]; p = 0.002) and improved model fit and marginally improved discrimination when added to a clinical variable model for mortality (Additional file 2: Table S1). The optimal Ang2 threshold was 9761 pg/ml. In the derivation population, 69.5% were Ang2-positive with a 21.3% (95% CI 7.3–35.3; p = 0.003) adjusted increased absolute risk of mortality. In the validation population, 63.5% were Ang2-positive with a 12.3% (95% CI 0.2–24.4; p = 0.046) unadjusted increased absolute risk of mortality (Table 2). In adjusted analyses, the RD in the validation population was 10.8% (95% CI − 1.1–22.6; p = 0.075). The Ang2 threshold did not consistently improve model fit and discrimination (Additional file 2: Table S2) and was not consistently superior to septic shock for prognostic enrichment (Fig. 3, Additional file 2: Tables S3 and S8).

Fig. 3.

a Net benefit curves of three clinical trial enrollment strategies: enrolling all sepsis patients (black line), enrolling patients with septic shock (blue line), and enrolling Ang-2 positive patients (red line). The x-axis represents the threshold probability, which is the probability of sepsis mortality that a hypothetical trial would require for enrollment. The y-axis is the net benefit, which represents the tradeoff between true positives and false positives, and is described further in the legend of Fig. 1. The net benefit curves are interpreted vertically, such that at each threshold probability, the strategy with the highest net benefit is the optimal strategy for enriching a trial with high-risk subjects. For example, if a trial sought to enroll patients with at least 35% mortality risk (dotted vertical line), enrolling only Ang-2 positive patients had a similar net benefit to enrolling only patients with septic shock. b Intervention curves comparing enrolling all sepsis patients (reference, not shown), enrolling patients with septic shock (blue line), and enrolling Ang-2 positive patients (red line). Intervention curves are an alternative representation of net benefit. The y-axis represents the number of survivors that avoid the intervention, which in this case is enrollment and exposure to unproven and potentially risky therapy. Intervention curves are also interpreted vertically. For example, at a threshold probability of 35%, enrolling only Ang-2-positive patients led to a similar reduction in the number of survivors exposed when compared to enrolling only patients with septic shock

Combinatorial and secondary models

Secondarily, we evaluated the combined enrichment potential of sTNFR1 and IL8. Positivity for both sTNFR1 and IL8 improved discrimination to a similar degree as the individual markers (Additional file 2: Table S9), and as an enrichment factor performed similarly to sTNFR1 alone and slightly outperformed IL8 alone (Additional file 2: Figure S2). This may be due to the effect modification of immunocompromised status on the IL8-mortality association, as positivity for both sTNFR1 and IL8 was superior when restricted to immunocompetent patients (Additional file 2: Figure S3). Using the predicted mortality from sTNFR1 and IL8 concentrations as continuous variables yielded similar discrimination as the individual marker thresholds, similar enrichment as positivity for sTNFR1 alone, and slightly superior enrichment as positivity for IL8 alone (Additional file 2: Table S9, Figure S4).

For our secondary clinical variable enrichment methods, an APACHE II score ≥ 20 yielded superior enrichment compared to sTNFR1 positivity and IL8 positivity at lower mortality thresholds, whereas sTNFR1 positivity was superior to an APACHE II ≥ 20 at mortality thresholds above 33% and IL8 positivity was superior at mortality thresholds above 36% (Additional file 2: Table S3, Figure S5). Positivity for sTNFR1 outperformed peak lactate ≥ 4 mmol/l, whereas IL8 positivity performed similarly (Additional file 2: Table S3, Figure S6).

Discussion

We found that plasma sTNFR1 and IL8 thresholds consistently identified subjects at higher mortality risk in two distinct populations of critically ill septic patients. We also demonstrated that sTNFR1 and IL8 could potentially serve as prognostic enrichment factors for sepsis trials. By selecting high-risk patients, using these markers could improve trial efficiency and power and reduce the number of survivors unnecessarily exposed to potentially risky therapies even more so than using septic shock.

Our results are consistent with a study by Mikacenic et al., which found that using sTNFR1 and IL8 concentrations in a continuous fashion could risk stratify sepsis patients [22]. Our data build on these findings by demonstrating that thresholds of these markers could provide a simpler method to refine trial enrollment, that the individual markers have enrichment potential and perform similarly to combined models, that the markers are superior to using septic shock for enrichment, and that the markers have prognostic value in patients with higher illness severity and mortality. Our data also reveal potential limitations of using IL8 for enrichment in immunocompromised patients, given our findings that the IL8 threshold was associated with higher mortality in immunocompetent subjects but not immunocompromised subjects.

Although we demonstrated that the Ang2 threshold identified high-risk patients, it did not appear to have utility over using septic shock for prognostic enrichment. This may be due to the association of dysregulated Ang2 with septic shock [37], suggesting both variables identified a similar high-risk subgroup and thus provided similar enrichment.

Our data add to the growing body of literature highlighting the potential benefits of biomarker-based enrichment for critical care trials. Recent sepsis trials have demonstrated a discrepancy between the estimated mortality based on clinical criteria and observed mortality [4, 38], which could result in inadequate power to detect a benefit of a tested therapy. Despite differing baseline mortality at our two sites, sTNFR1 positivity consistently identified subjects with at least 17.8% higher mortality risk, and IL8 positivity consistently identified immunocompetent patients with at least 17.7% higher mortality risk. These markers could potentially provide a method to ensure adequate baseline mortality in future trials.

Our study has several strengths. We performed a two-center cohort study, enrolling two distinct populations with a wide distribution of ages, diverse racial makeup, and differences in illness severity. Our use of plasma thresholds simulated operationalizing the markers as simple methods for trial enrichment. The biomarkers were measured as close to admission as possible, demonstrating they have prognostic relevance in early sepsis when most trials seek to enroll patients. We used risk differences to provide easily interpretable predictive values and employed decision curves, a novel method to evaluate biomarkers [39, 40], to compare enrichment strategies.

Our study also has limitations. Although we successfully derived and validated thresholds of each marker that consistently identified patients at higher risk of mortality in both cohorts, the improvements in discrimination when the markers were added to clinical variables were relatively incremental. In addition, although the marker thresholds outperformed an APACHE-based method at higher mortality thresholds, the APACHE-based method was superior at lower mortality thresholds. This may ultimately limit each marker’s utility as simple prognostic enrichment factors, given the APACHE score can be obtained from clinical data at no additional cost, and several barriers still need to be addressed to improve the feasibility and practicality of employing biomarker enrichment strategies, such as advances in rapid testing and validation of testing for clinical use [15]. In addition, we identified that the IL8 threshold’s utility as a prognostic enrichment factor was limited to immunocompetent patients, further limiting its potential as a sole enrichment factor given the frequency of sepsis among immunocompromised patients and because immune impairment may be unrecognized at the time of ICU admission. Although we selected these markers because of their prior association with sepsis mortality and their representation of pathways for which therapies are being developed, using these markers for prognostic enrichment may inadvertently select mechanistically distinct subgroups, which could limit the generalizability of clinical trials that use these markers for prognostic enrichment. Furthermore, other plasma markers and clinical variable enrichment methods may deserve consideration as prognostic enrichment factors in future studies.

We also recognize that the confidence intervals for the risk differences in mortality were moderately wide. However, the goal of using risk differences as predictive values was not for individual prognostication, but only to guide trial enrollment. Given the strength of the association in two distinct cohorts and the decision curve analysis demonstrating the potential value of using each marker when compared to clinical variable methods, these markers appear to have potential as prognostic enrichment factors. Larger studies may be needed to confirm our findings and refine the use of these markers as prognostic enrichment factors, which may include further refining the biomarker thresholds. It is also important to note that the mortality among marker-negative patients (false negatives) was not inconsequential. However, one benefit of DCA is that it does not make assumptions about the relative harms of false positives and false negatives, leaving it to the trialist to define their importance by choosing the threshold probability. If a trialist’s priority was minimizing the exclusion of non-survivors (i.e., minimizing false negatives), as would be the case for a trial of an inexpensive, low-risk therapy with a high likelihood of benefit, the trialist would set a low mortality threshold (i.e., enroll all patients with sepsis). Alternatively, if a trialist was concerned about potentially high-risk side effects from an experimental therapy, they might consider it necessary to exclude patients with low mortality risk and set a higher threshold even though some non-survivors would be excluded. Thus, the relative importance of false negatives and false positives varies based on the probability threshold, and the DCA provides a method for comparing enrollment strategies at each threshold.

Lastly, an important limitation of our study is that we were unable to evaluate the predictive enrichment potential of sTNFR1, IL8, and Ang2. Sepsis is a heterogeneous syndrome with myriad pathways contributing to organ dysfunction and death. Several recent studies have highlighted heterogeneity in the treatment effect of therapies in sepsis and suggest biomarkers could identify patients more likely to respond to therapy. In a prospective trial, sepsis patients with higher baseline interleukin-6 levels appeared more likely to respond to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy [41]. In retrospective analyses, biomarker-based strategies identified heterogeneity in treatment effect in sepsis trials of recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and anti-TNF-α antibody therapy [42, 43]. Similarly, studies have shown heterogeneity in treatment effect among patients with a hyperinflammatory subphenotype of ARDS [44–46]. Because sTNFR1, IL8, and Ang2 reflect pathways that are dysregulated in sepsis and for which therapies are being investigated, such as monoclonal antibodies targeting IL8 and TNF [16–18], they should be evaluated as predictive enrichment factors for their designated therapies in future trials.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that plasma levels of sTNFR1 and IL8 consistently identified sepsis patients at higher risk of mortality and might be useful as prognostic enrichment factors in future trials by improving trial efficiency and power and reducing the number of survivors unnecessarily exposed to potentially risky therapy.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Supplemental Methods.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge David Lipson, M.D., for his help in study conception, design, and obtaining funding.

Abbreviations

- sTNFR1

Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1

- IL8

Interleukin 8

- Ang2

Angiopoietin-2

- RD

Risk difference

- PENN

University of Pennsylvania

- UCSF

University of California San Francisco

- APACHE

Acute Physiology, Age, Chronic Health Evaluation

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- DCA

Decision curve analysis

- OR

Odds ratio

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- NPV

Negative predictive value

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design were done by NJM, MAM, CSC, ALL, AIB, and JDC. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data was performed by BJA, NJM, KDL, JPR, KNK, MGSS, ALL, AIB, RJG, TAM, TGD, EJ, JA, AJ, TD, KV, AB, HZ, MAM, CSC, and JDC. Drafting of the manuscript was done by BJA and NJM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was performed by KDL, JPR, KNK, MGSS, ALL, AIB, RJG, TAM, TGD, EJ, JA, AJ, TD, KV, AB, HZ, MAM, CSC, and JDC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline R&D (JDC, NJM, CSC, MAM), American Thoracic Society Foundation Award (BJA), and National Institutes of Health grants HL140482 (BJA), HL125723 (JPR), HL137006 (NJM), HL140026 (CSC), HL051856 (MAM), and HL115354 (JDC).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Molecular Epidemiology of SepsiS in the IUC (MESSI) cohort study is approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. The Early Assessment of Renal and Lung Injury (EARLI) cohort study is approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors NJM, MAM, CSC, and JDC receive grant support from GlaxoSmithKline to study biomarkers in sepsis. Authors AIB and ALL are employed by GlaxoSmithKline. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nuala J. Meyer and Jason D. Christie contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13054-019-2684-2.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gohil K. Sepsis treatment options are often lacking. Pharm Ther. 2015;40(7):466–467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perner A, Gordon AC, Angus DC, et al. The intensive care medicine research agenda on septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(9):1294–1305. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4821-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Investigators PCESS, Yealy DM, Kellum JA, et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1683–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA. 2014;311(19):1998–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoadley KA, Yau C, Wolf DM, et al. Multiplatform analysis of 12 cancer types reveals molecular classification within and across tissues of origin. Cell. 2014;158(4):929–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta C, Schafer H, Daniel H, et al. Biomarker driven population enrichment for adaptive oncology trials with time to event endpoints. Stat Med. 2014;33(26):4515–4531. doi: 10.1002/sim.6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prescott HC, Calfee CS, Thompson BT, et al. Toward smarter lumping and smarter splitting: rethinking strategies for sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome clinical trial design. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(2):147–155. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2544CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temple R. Enrichment of clinical study populations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(6):774–778. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freidlin B, Korn EL. Biomarker enrichment strategies: matching trial design to biomarker credentials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(2):81–90. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankar-Hari M, Rubenfeld GD. The use of enrichment to reduce statistically indeterminate or negative trials in critical care. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(5):560–565. doi: 10.1111/anae.13870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, et al. Sepsis: a roadmap for future research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):581–614. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opal SM, Dellinger RP, Vincent JL, et al. The next generation of sepsis clinical trial designs: what is next after the demise of recombinant human activated protein C?*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(7):1714–1721. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seymour CW, Gomez H, Chang CH, et al. Precision medicine for all? Challenges and opportunities for a precision medicine approach to critical illness. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1836-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu P, Cui X, Sun J, et al. Antitumor necrosis factor therapy is associated with improved survival in clinical sepsis trials: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(10):2419–2429. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182982add. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolgin E. BMS bets on targeting IL-8 to enhance cancer immunotherapies. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(10):1006–1007. doi: 10.1038/nbt1016-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skov L, Beurskens FJ, Zachariae CO, et al. IL-8 as antibody therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases: reduction of clinical activity in palmoplantar pustulosis. J Immunol. 2008;181(1):669–679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiehl T, Thamm K, Kaufmann J, et al. Lung-targeted RNA interference against angiopoietin-2 ameliorates multiple organ dysfunction and death in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(10):e654–e662. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.David S, Ghosh CC, Kumpers P, et al. Effects of a synthetic PEG-ylated Tie-2 agonist peptide on endotoxemic lung injury and mortality. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300(6):L851–L862. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00459.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang JA, Lee EH, Lee SD, et al. COMP-Ang1 ameliorates leukocyte adhesion and reinforces endothelial tight junctions during endotoxemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381(4):592–596. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikacenic C, Price BL, Harju-Baker S, et al. A two-biomarker model predicts mortality in the critically ill with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(8):1004–1011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201611-2307OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal A, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN, et al. Plasma angiopoietin-2 predicts the onset of acute lung injury in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(7):736–742. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1460OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly JP, Anderson BJ, Hudock KM, et al. Neutropenic sepsis is associated with distinct clinical and biological characteristics: a cohort study of severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):222. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1398-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100(6):1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norton EC, Miller MM, Kleinman LC. Computing adjusted risk ratios and risk differences in Stata. Stata J. 2013;13(3):492–509. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1301300304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, et al. Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(6):362–366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickers AJ. Decision analysis for the evaluation of diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. Am Stat. 2008;62(4):314–320. doi: 10.1198/000313008X370302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM. Traditional statistical methods for evaluating prediction models are uninformative as to clinical value: towards a decision analytic framework. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(1):31–38. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vickers AJ, Van Calster B, Steyerberg EW. Net benefit approaches to the evaluation of prediction models, molecular markers, and diagnostic tests. BMJ. 2016;352:i6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):877–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S, et al. Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1412–1421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):775–787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.David S, Mukherjee A, Ghosh CC, et al. Angiopoietin-2 may contribute to multiple organ dysfunction and death in sepsis*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(11):3034–3041. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825fdc31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opal SM, Laterre PF, Francois B, et al. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309(11):1154–1162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Localio AR, Goodman S. Beyond the usual prediction accuracy metrics: reporting results for clinical decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(4):294–295. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitzgerald M, Saville BR, Lewis RJ. Decision curve analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(4):409–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panacek EA, Marshall JC, Albertson TE, et al. Efficacy and safety of the monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody F (ab')2 fragment afelimomab in patients with severe sepsis and elevated interleukin-6 levels. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2173–2182. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000145229.59014.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer NJ, Reilly JP, Anderson BJ, et al. Mortality benefit of recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist for sepsis varies by initial interleukin-1 receptor antagonist plasma concentration. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(1):21–28. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong HR, Lindsell CJ. An enrichment strategy for sepsis clinical trials. Shock. 2016;46(6):632–634. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Famous KR, Delucchi K, Ware LB, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes respond differently to randomized fluid management strategy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(3):331–338. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0645OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calfee CS, Delucchi K, Parsons PE, et al. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(8):611–620. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calfee CS, Delucchi KL, Sinha P, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes and differential response to simvastatin: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(9):691–698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplemental Methods.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.