Abstract

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is characterized by the expansion of fluid-filled cysts in the kidney, which impair the function of kidney and eventually leads to end-stage renal failure. It has been previously demonstrated that transgenic overexpression of prothymosin α (ProT) induces the development of PKD; however, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, we used a mouse PKD model that sustains kidney-specific low-expression of Pkd1 to illustrate that aberrant up-regulation of ProT occurs in cyst-lining epithelial cells, and we further developed an in vitro cystogenesis model to demonstrate that the suppression of ProT is sufficient to reduce cyst formation. Next, we found that the expression of ProT was accompanied with prominent augmentation of protein acetylation in PKD, which results in the activation of downstream signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3. The pathologic role of STAT3 in PKD has been previously reported. We determined that this molecular mechanism of protein acetylation is involved with the interaction between ProT and STAT3; consequently, it causes the deprivation of histone deacetylase 3 from the indicated protein. Conclusively, these results elucidate the significant role of ProT, including protein acetylation and STAT3 activation in PKD, which represent potential for ameliorating the disease progression of PKD.—Chen, Y.-C., Su, Y.-C., Shieh, G.-S., Su, B.-H., Su, W.-C., Huang, P.-H., Jiang, S.-T., Shiau, A.-L., Wu, C.-L. Prothymosin α promotes STAT3 acetylation to induce cystogenesis in Pkd1-deficient mice.

Keywords: polycystic kidney disease, HDAC3, tubulogenesis

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) has a prevalence of 1 in 500 and is one of the most common fatal genetic renal diseases. It is characterized by the formation of fluid-filled renal cysts and leads to end-stage renal disease (1). Abnormality of the polycystic kidney disease (Pkd) 1 or Pkd2 genes, which encode polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively, causes ADPKD; both polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 are transmembrane proteins and function in cell-cell/matrix interactions, tissue development, mechanical sensors, and calcium signaling (2). Cystic epithelial cells exhibit various physiologic aberrations, such as abnormal proliferation of renal epithelial cells (1), dysfunction of primary cilia (3–5), and dysregulation of extracellular matrix remodeling (6). In the molecular pathologic mechanism of cystic epithelia, several signal transduction pathways are known to be abnormal in cyst progression, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), TGF-β/Smad, and the Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway (7), and several molecules targeting these signaling pathways have been developed to decrease cyst expansion in mice PKD models. Even though tolvaptan, a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist, has been approved in clinical treatment of ADPKD, detailing the molecular pathologic mechanisms of cyst progression is essential for disease therapy.

Prothymosin α (ProT) exists from yeast to mammalian cells is a highly conserved nuclear protein, the expression of which is found in most tissue, implying its necessity in cells (8). ProT has cellular functions associated with the cell cycle, cell survival, and chromatin remodeling. Suppression of ProT decreases cell growth and increases in ProT to promote cell proliferation (8); a high expression of ProT is observed in many kinds of tumors and is associated with cancer malignancy (9). ProT also inhibits necrosis and apoptosis while neuron cells suffer from ischemia or serum-starvation stress, emphasizing its role in cell survival and neuron protection (10–12). Aside from these physiologic functions, ProT is an important regulator of histone acetylation, which is related to chromatin remodeling (13). It is known that in addition to histones, the enhanced acetylation of other proteins such as p53, NF-κB, and Smad7 are accompanied with increases in ProT, whereas more and more evidence suggests that ProT regulates various physiologic mechanisms in an acetylation-dependent manner. The interaction of ProT with histone acetyltransferases, cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB), or p300 leads to increases in activator protein 1 (AP1)-dependent and NF-κB–dependent transcription (14–16). Overexpression of ProT elicits a p53 response that involves an increase in p53 acetylation (17). The acetylation of Smad7 is up-regulated by ProT and plays a crucial role in emphysema (18, 19).

The link between ProT and PKD was first demonstrated in our group, where it was found that overexpression of ProT induces the development of PKD (20); however, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Previous studies have shown that ProT accelerates cell cycle progression, and the cyst-lining epithelial cells show a similar proliferating property. The transcription factor myc is an upstream regulator of ProT, and an increase of myc was detected in human and mouse PKD (21, 22). This evidence strongly supports the significance of ProT in PKD. Recent studies show the pivotal roles of STAT3 in cyst expansion, in which hyperactivation of STAT3 has been observed in cystic epithelial cells, and inhibition of STAT3 suppresses cyst growth in mouse PKD models (23). Here, we elucidate that ProT is involved in the polycystin-1 signaling pathway and downstream increases in protein acetylation, including STAT3, resulting in an increase of its transcriptional activity that exaggerates cyst formation. These findings demonstrate the significance of ProT and detail a novel mechanism of STAT3 activation in PKD that may provide a new concept for disease therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and clinical samples

Pkd1 low-expressing mice and ProT overexpressing mice were generated and screened as previously described by Jiang et al. (24). The experimental protocol adhered to the rules of the Animal Protection Act of Taiwan and was approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of National Cheng Kung University. Clinical samples were collected from 9 patients with a diagnosis of PKD who underwent surgery in the Urological Division, Department of Surgery of National Cheng Kung University Hospital. The samples that served as the normal controls were from the nontumor parts of the resected lobes of 4 patients who had undergone surgery for renal carcinoma, and the patient data were shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient data

| Patient no. | Sex/age (yr) | Pathologic diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Male/42 | PKD |

| P2 | Male/61 | Renal cell carcinoma, PKD |

| P3 | Male/68 | Renal transitional cell carcinoma, PKD |

| P4 | Male/69 | Renal cell carcinoma, PKD |

| P5 | Female/7 | Chronic pyelonephritis, PKD |

| P6 | Female/7 | PKD |

| P7 | Female/32 | Chronic pyelonephritis, PKD |

| P8 | Female/32 | Renal cell carcinoma, PKD |

| P9 | Female/61 | PKD |

Tubulogenesis assay

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells that had stably expressed small hairpin RNA (shRNA) were trypsinized to a single-cell suspension, and 2 × 104 cells were seeded into 1 ml of ice-cold collagen gel that was prepared as previously described by Santos et al. (25). Briefly, 10 times DMEM medium and buffer composed of 0.26 M sodium bicarbonate (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) and 0.2 M HEPES (MilliporeSigma) were mixed with type I collagen (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) that had been diluted as 1.5 mg/ml in a ratio of 1:1:8. The suspended MDCK cells were dispensed in collagen gel in a 6-well plate for 20 min at 37°C and the collagen gel was subsequently overlaid with culture medium with 10 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor. After 3 d, the morphology was observed using a light microscope. For quantification, the ability of tubulogenesis (tubulogenesis index) was indicated by the circumference length of tubes and cysts in each group; tubule phenotype may show grater length than cystic phenotype.

Cells and plasmids

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells and MDCK cells were respectively obtained from National RNAi Core Facility (Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan), and the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All cells were cultured with DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and gentamycin (100 μg/ml), at 37°C in 5% CO2.

pcDNA3.1-HADC3-Flag plasmid was purchased from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). STAT3 plasmid was generously provided by Dr. T. Hirano (26). The plasmids used in this study were constructed as follows: To generate STAT3-hemagglutinin (HA) plasmid, point mutation of stop codon in STAT3 was available by PCR and subsequently ligated with HA epitope cDNA that was generated by annealing 2 oligonucleotides that encode the HA epitope. Myc epitope–tagged ProT was previously described by Su et al. (19), and HA epitope–tagged ProT was available from replacing the STAT3 cDNA in STAT3-HA plasmid with ProT cDNA. pCMV-V5 plasmid was generated by excising a flag region in pCMV-Tag 4A (StrataGen, Redmond, WA, USA) and then inserting V5 cDNA, and ProT was cloned into pCMV-V5 plasmid to generate ProT-V5 plasmid.

Lentiviral vectors

The shRNA design for the canine Pkd1 gene was obtained from G. Luca Gusella (27). The fragments were generated by annealing 2 oligonucleotides, 5′-GATCCGCCACGTGAGCAACGTCACCATTAGATCAGG TGACGTTGCTCACGTGGTTTTTTGGAAAT-3′ and 5′-CGATTTCCAAAAAACCACGTGAGCAACGTCACCTGATCTAATGGTGACGTTGCTCACGTGGCG-3′ and then inserted downstream of the H1 promoter in the pSuper vector (Oligoengine) between BglII (AGATCT) and ClaI (ATCGAT) restriction sites to generate pSuper/small hairpin PKD (shPKD) 1. The shRNA expression cassette containing the sequences for the H1 promoter and shPKD1 was recovered from the pSuper/shPKD1 plasmid through EcoRI (GAATTC) and ClaI digestion and further ligated into the same site as that of the lentiviral transfer plasmid pLVTHM (a kind gift from Dr. D. Trono; Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland), resulting in the pLVTHM/shPKD1 plasmid expressing both canine Pkd1 shRNA and green fluorescent protein (GFP). Next, the GFP was substituted for a zeocin-resistant gene, resulting in the shPkd1-zeo plasmid. The control vector, small hairpin GFP (shGFP)-zeo, arose from replacing the shPKD1 region with shGFP that came from the pLVTH-shGFP vector (a kind gift from Dr. D. Trono). pLKO.1-puro–based lentiviral vectors including stem-loop cassettes encoding shRNA for shPkd1-1 and 2 (TRCN0000062322 and 0000062321); small hairpin ProT (shProT)-1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (TRCN0000125360, 0000125359, 0000135421, 0000138750, and 0000125363); and shGFP (TRCN0000072181) were purchased from obtained from Academia Sinica. The targeting sequences of all shRNA we used were indicated as follows: shPKD1#1, 5′-GTCCGTCTTTGGCAAGACATT-3′; shPKD1#2, 5′-GCTATGGAGAGAGTTCCTCTT-3′; shPkd1#3, 5′-CCACGTGA GCAACGTCACC-3′; shProT#1, 5′-GCTGACAATGAGGTAGATGAA-3′; shProT#2, 5′-CTGTACTATAAGTAGTTG GTT-3′; shProT#3, 5′-GTAGACGAAGAAGAGGAAGAA-3′; shProT#4, 5′-GAAGTTGTGGAAGAGGCAGAA-3′; shProT#5, 5′-GAGGCAGAGAATGGAAGAGAT-3′; shGFP, 5′-ACAACAGCCACAACGTCTATA-3′. Recombinant lentiviruses expressing shRNA were individually produced by the transient transfection of HEK293T cells with the lentiviral transfer plasmid along with the psPAX2 plasmid that expressed virus packaging protein and the vesicular stomatitis virus–G protein (VSV-G) expression plasmid pMD2G (a kind gift from Dr. D. Trono), and viruses were collected from the media ∼48 h after transfection.

Immunologic assays

For the immunohistochemical studies, 5-mm–thick sections of paraffin-embedded human or mouse kidney tissue blocks were prepared, deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated with graded alcohol. The primary antibodies used included monoclonal antibodies against ProT [clone 2F11, ascites fluid (28)], phosphorylated STAT3 (Y705) (1:50; GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA), and polyclonal antibodies against acetylated lysine (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Tissue sections were placed in a citrate-buffered solution (pH 6.0) and then boiled for 30 min for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide, and nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin. Subsequently, the samples were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit IgG at room temperature for 2 h. The reactivity was visualized with aminoethyl carbazole (red color, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and counterstained with hematoxylin. The color intensity of immunostaining was analyzed by ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Immunoblotting was performed using standard methods. Total cell lysates were prepared and variant proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE. Next, the protein samples were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (MilliporeSigma); subsequently, the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 1 h. The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting included antibodies against ProT (clone 2F11) (28), polycystin-1 (sc-130554; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), β-actin (ab6276; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), acetyl-lysine (#9941s; Cell Signaling Technology), acetyl-STAT3 (Lys685) (2523; Cell Signaling Technology), myc (sc-40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), STAT3 (sc-8019; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and HA (ab9110; Abcam). Flag (F1804; MilliporeSigma, 20543-1-AP; Proteintech (Chicago, IL, USA)), V5 (66007-1-Ig; Proteintech) phosphorylated STAT3 (GTX61820; GeneTex), α-tubulin (sc-5286; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit IgG (115-035-003 and 111-035-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) were used as secondary antibodies. Protein-antibody complexes were detected using the ECL system (MilliporeSigma) and visualized with a Biospectrum AC imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA, USA).

The coimmunoprecipitation assay was performed generally using standard methods. In this study, the antibody-conjugated beads included M2-Flag beads, and monoclonal anti–HA-agarose (A2220 and A2095; MilliporeSigma) were incubated with total cell lysates to immunoprecipitate histone deacetylase (HDAC)3-flag and STAT3-HA; normal mouse IgG (sc-3877; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that has been previously incubated with protein A/G agarose beads was used in control precipitation. A Western blot was performed subsequently for the indicated proteins.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat 3.5 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). All data were expressed as means ±sem. A Student’s t test was conducted to compare the between-group differences. The multiple comparisons were assessed with 1-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

PKD is associated with aberrant expression of ProT

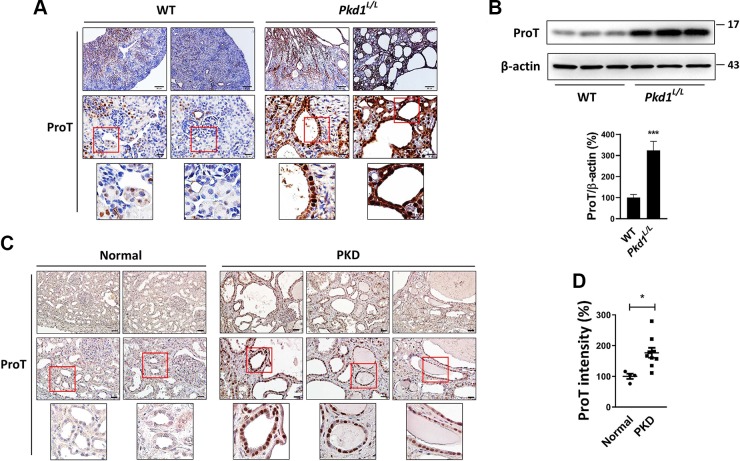

To determine whether ProT is involved in PKD, we evaluated the expression of ProT in a mouse PKD model. Mice with kidney-specific low-expression of Pkd1 gene (Pkd1L/L) develop multiple renal cysts (24), which is accompanied by an aberrant increase in ProT expression in cyst-lining epithelium compared with wild-type (WT) epithelium (Fig. 1A). Western blotting of total kidney lysate also shows higher level of ProT in Pkd1L/L kidney as compared with WT kidney (Fig. 1B). We next explored the expression of ProT in human PKD samples using an immunostaining assay. As shown in Fig. 1C, cystic epithelium showed a significant heavy staining of ProT compared with normal kidney. The immunoreactivity of ProT in normal (n = 4) and PKD (n = 9) specimens was quantified and shown in Fig. 1D.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of ProT in PKD. A) The kidneys of WT and Pkd1L/L mice were assayed for ProT expression using immunostaining. ProT shows heavy staining in Pkd1L/L kidney compared with WT kidney, and cyst-lining epithelial cells in the Pkd1L/L kidney show more intense staining. B) Western blotting for ProT expression in mice kidney samples. The total protein lysates were obtained from 3 WT and Pkd1L/L mice. Immunoblotting indicated the abundance of ProT in the Pkd1L/L kidney compared with WT kidney, whereas β-actin served as the loading control. Quantification data (means ± sem; Student’s t test) were obtained from 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001. C) The immunostaining for ProT in human samples. The kidney with PKD showed extreme ProT expression in cyst-lining epithelial cells. The photos are displayed at original magnifications, ×100 (left panel) and ×400 (middle panel). All photos are displayed at original magnifications, ×100 (left panel) and ×400 (medium panel). D) Quantification result of human samples (normal, n = 4; PKD, n = 9). Values (means ± sem; Student’s t test) shown are levels of ProT staining intensity that were measured by ImagePro Plus software. *P < 0.05.

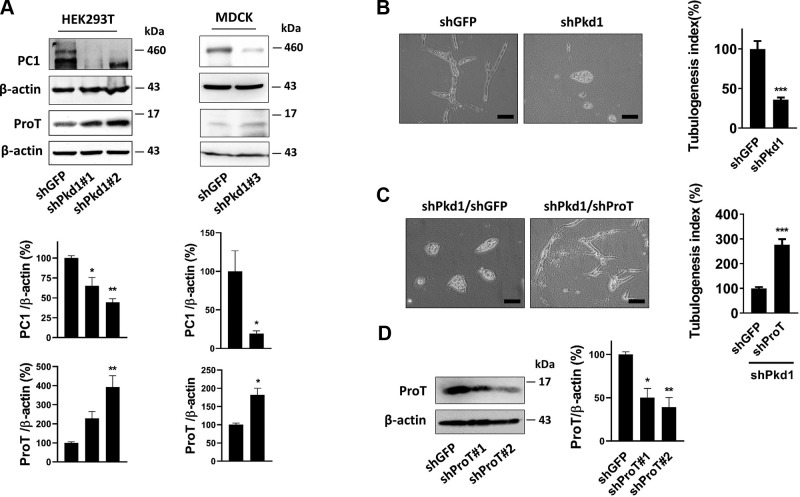

Based on the results above, we further examined the correlation between ProT and Pkd1. We generated 2 Pkd1 knockdown cell lines by lentivirus transfer of Pkd1 short-hairpin RNA (shRNA), which efficiently suppressed the expression of Pkd1 in HEK293T cells and MDCK cells, respectively. Knockdown of Pkd1 caused an apparent increase in ProT expression compared with the control groups (shGFP) (Fig. 2A). We next questioned whether overexpression of ProT plays a crucial role in cyst formation. We performed an in vitro cystogenesis model by using MDCK cells, which were cultured in a 3-dimensional collagen gel and could develop either a cystic or tubule phenotype while being treated with various substances. Knockdown of Pkd1 in MDCK has been known to cause cyst formation in vitro (27), and our experiments also confirmed this result (Fig. 2B). However, further suppression of ProT in Pkd1 knockdown cells (shPKD1/shProT) significantly reversed more cells from the cystic phenotype to the tubule phenotype compared with the control group (shPKD1/shGFP) (Fig. 2C). Taken together, our results showed that aberrant overexpression of ProT occurred in PKD and that ProT was involved in the Pkd1-signaling pathway. Additionally, cyst formation induced by defective expression of Pkd1 was restored to the tubule phenotype by inhibiting the expression of ProT, suggesting the pathologic significance of ProT in cyst formation.

Figure 2.

Suppression of ProT attenuated cyst formation. A) Lentivirus-mediated shPkd1 transfer stably reduced Pkd1 expression in the HEK293T and MDCK cell lines. Western blotting showed that knockdown of Pkd1 increased ProT expression in both cell lines, where β-actin was the loading control. shPkd1#1, 2, and 3 symbolized distinct targeting sequences for the Pkd1 gene. All immunoblotting experiments were independently performed 3 times and quantification data presented as means ± sem, 1-way ANOVA (HEK293T), and Student’s t test (MDCK). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. B) MDCK stably expressing shPkd1 or shGFP was cultured with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (20 ng/ml) in a 3-dimensional collagen gel; after 72 h, knockdown of Pkd1 in MDCK displayed a greater amount of the cystic phenotype compared with knockdown GFP. Further knockdown of ProT in shPkd1-MDCK cells revealed an increase in the tubule phenotype compared with further knockdown of GFP. C) These photos were shown at an original magnification, ×200. The experiments were independently performed at least 3 times, and the fields were randomly selected at an original magnification, ×4 to measure the circumference of each colony (cyst and tube; mean ± sem) by MetaMorph software and quantified using a Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001. D) The knockdown efficiency of shProT in MDCK cells. The experiment was independently performed 3 times and statistical results were presented as means ± sem, Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and shProT#2 was used to perform the 3-dimensional culture shown in C.

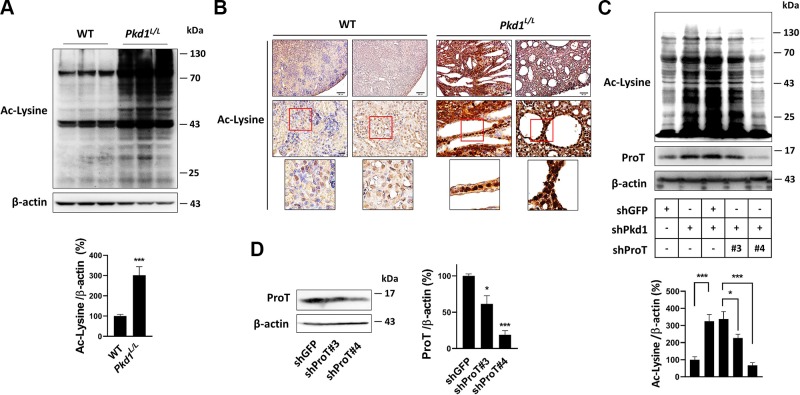

ProT increases protein acetylation in PKD

Accumulated evidence shows that ProT is involved in the regulation of protein acetylation, whereas protein acetylation in PKD is unclear. It has been shown that curcumin, a natural product, functions as an inhibitor of p300 acetyltransferase, which indicates a possible therapeutic effect for PKD (29), suggesting abundant protein acetylation may occur in PKD. According to these rationales, we accessed the amounts of protein acetylation in Pkd1L/L and WT kidneys using immunoblotting. The results showed that obvious increases in protein acetylation were detectable in Pkd1L/L kidney compared with WT kidney (Fig. 3A). Immunostaining also showed greater amounts of protein acetylation in Pkd1L/L kidney than in WT kidney (Fig. 3B). To further determine whether the increase in protein acetylation in Pkd1L/L kidney was related to the aberrant overexpression of ProT, we silenced the expression of Pkd1 in HEK293T cells, which led to an increase in protein acetylation; however, further suppression of the expression of ProT in Pkd1 knockdown cells (shPkd1/shProT) resulted in a reversed pattern of protein acetylation compared with the control group (shPkd1/shGFP) (Fig. 3C). Collectively, our results showed defective expression of Pkd1 augments broad protein acetylation both in vitro and in vivo, and we further demonstrated that ProT plays a pivotal role in the augmentation of protein acetylation, where the knockdown of ProT in Pkd1-deficient cells lowered the expression of protein acetylation.

Figure 3.

ProT induced protein acetylation in Pkd1-knockdown cells. A) The detection of protein acetylation by Western blotting. Total protein lysates of WT (n = 3) and Pkd1L/L (n = 3) kidney were probed with antibodies against the protein with acetyl-lysine residue, which indicated that the Pkd1L/L kidney showed increased protein acetylation compared with the WT kidney. B) A similar result was obtained with immunostaining, where the amounts of protein acetylation were obviously increased in the Pkd1L/L kidney. C) In the HEK293T cells, knockdown of Pkd1 enhanced protein acetylation (lanes 1 and 2), whereas further knockdown of ProT in the Pkd1-knockdown cells revealed a reversed pattern compared with the knockdown control, shGFP (lanes 3, 4, and 5). The clones of shProT used in lanes 4 and 5 were shProT#3 and shProT#4, respectively. D) The knockdown ability of shProT in HEK293T cells. β-Actin served as an internal control. All immunoblotting experiments were independently performed 3 times. The statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test (A) and 1-way ANOVA (C, D). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

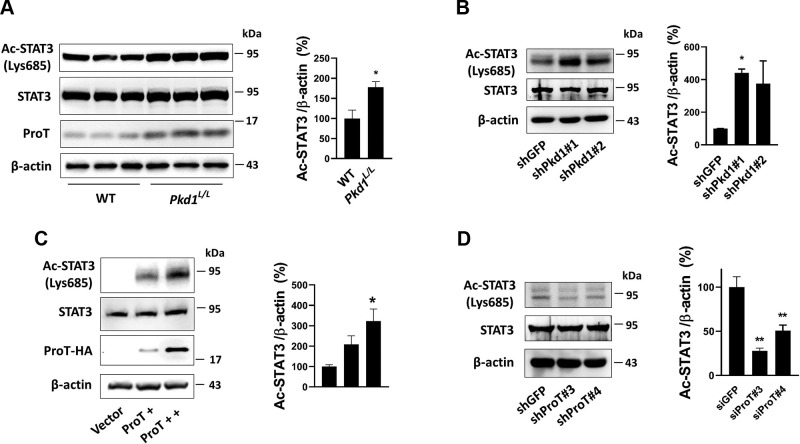

ProT increases the acetylation of STAT3 in PKD

STAT3 regulates many cellular processes, including differentiation, apoptosis, and proliferation, and we know that hyperactivation of STAT3 is associated with the acceleration of cyst progression (23, 29). Activation of STAT3 depends on its phosphorylation on tyrosine 705 residue, which causes its dimerization and translocation into the nucleus to process transcriptional regulation, whereas acetylation of STAT3 on Lys685 residue is required to stabilize the dimer form and enhance transcriptional activity (30).

To determine whether an increase of STAT3 acetylation on Lys685 residue occurs in PKD, we performed an immunoblotting assay, which showed STAT3 acetylation in Pkd1L/L kidney was significantly higher than that in WT kidney (Fig. 4A). Similarly, cell experiments also showed that knockdown of Pkd1 in HEK293T cells increased STAT3 acetylation compared with the knockdown control (shGFP) (Fig. 4B). We have determined that ProT increases protein acetylation in Pkd1 low-expressing cells both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3A–C), suggesting that an increase in STAT3 acetylation might be regulated by ProT. To further examine this issue, we transfected with ProT in HEK293T cells, which caused an increase in STAT3 acetylation; however, knockdown of ProT reduced the expression of acetyl-STAT3 (Fig. 4C, D).

Figure 4.

ProT induced STAT3 acetylation. A) The detection of STAT3 acetylation in WT and Pkd1L/L kidney. The total protein lysate of kidney was assayed by probing acetyl-STAT3 onto a Lys685 residue. B) Stable knockdown of Pkd1 in HEK293T cells increased acetyl-STAT3 expression. C) Transient transfecting with exogenous ProT with HA tag on HEK293T cells and the expression of acetyl-STAT3 was detected. D) Oppositely, knockdown of ProT was performed to detect the expression of acetyl-STAT3. The results showed the expression of acetyl-STAT3 was increased/decreased during overexpression/suppression of ProT, respectively. The β-actin served as the loading control. All immunoblotting experiments were independently performed 3 times. The statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test (A) and 1-way ANOVA (B–D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

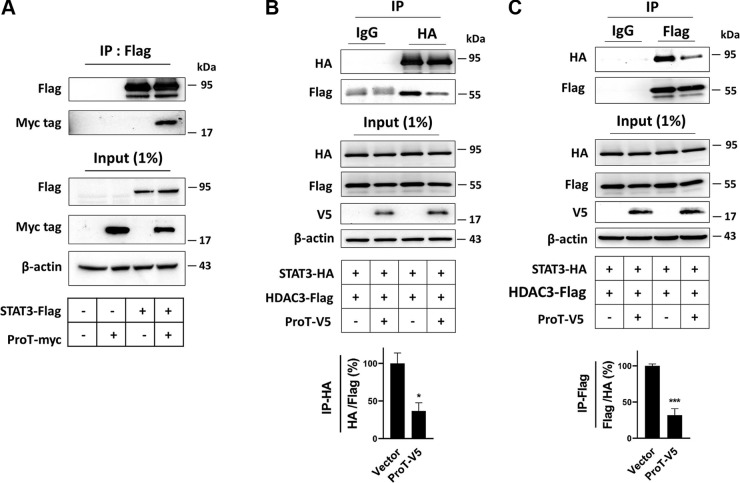

The molecular mechanism demonstrated that ProT increases protein acetylation by binding with the target protein, preventing the target protein from interaction with its correlative protein deacetylase (18, 19). ProT has been shown to interact with STAT3 using a yeast 2-hybridization assay (31), and our data also confirmed this result using immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A). The acetylation of STAT3 mediated by p300 acetyltransferase can be reduced by HDACs, and HDAC3 is very efficient with regard to decreasing STAT3 acetylation (30). We therefore used HDAC3 in our experiments to examine whether ProT-mediated enhancement of STAT3 acetylation could be ascribed to a similar mechanism. Overexpression of ProT led to a smaller amount of HDAC3 being pulled down along with STAT3 compared to the corresponding control cells (Fig. 5B). Oppositely, in reverse immunoprecipitation, a similar result was obtained, where lower amounts of STAT3 were pulled down along with HDAC3 in ProT overexpression cells than was the case in the control cells (Fig. 5C). Summarily, our findings suggest that an increase of acetyl-STAT3 could be observed in Pkd1 low-expressing cells both in vitro and in vivo, which should be a result of aberrant overexpression of ProT in those cells, whereas the overexpression of ProT thereby caused the deprivation of HDAC3 from the interaction with STAT3, and therefore resulted in an increase in STAT3 acetylation.

Figure 5.

ProT deterred the interaction between STAT3 and HDAC3, which increased STAT3 acetylation. A) Coimmunoprecipitation of STAT3 and ProT. HEK293T cells cotransfected with ProT plasmids with a myc epitope and STAT3 with a flag epitope. After 24 h, STAT3 was pulled down by anti-flag M2 beads and detected by the flag and myc antibodies. B) Coimmunoprecipitation of HDAC3, ProT, and STAT3. HEK293T cells cotransfected with the 3 plasmids, including ProT with V5, STAT3 with HA, and HDAC3 with a flag epitope. After 24 h, STAT3 was precipitated by HA antibodies that had been connected with the protein A/G agarose bead. The protein precipitates were assayed using a probing flag and HA. C) The reverse coimmunoprecipitation was shown. In contrast to the previous description, HDAC3 was precipitated using anti-flag M2 beads. The control precipitates were derived from the precipitation of a protein A/G agarose bead conjugated with control IgG. These results showed overexpression of ProT decreased the binding capacity of STAT3 and HDAC3 in HEK293T cells. All immunoblotting experiments were independently performed 3 times. The statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

ProT increases STAT3 activation in PKD

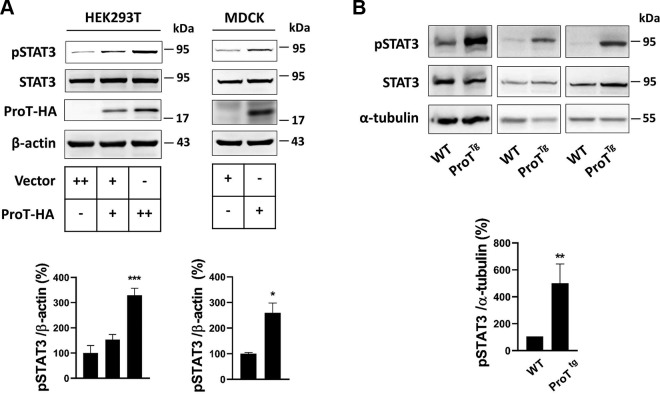

Given that ProT increases STAT3 acetylation, we suggested that ProT would inevitably increase the activation of STAT3. Immunoblotting showed that overexpression of ProT in both HEK293T and MDCK cells was accompanied with an increase in STAT3 activation (Fig. 6A), whereas a similar result could be obtained in ProT transgenic kidney (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

ProT increased STAT3 activation. A) Transient transfection with ProT in HEK293T and MDCK cell lines after 24 h showed the expression of phosphorylated STAT3 (Tyr705). B) Total protein lysates of WT (n = 3) and ProT transgenic kidney (n = 3) were extracted, and the expression of phosphorylated STAT3 was assayed. β-Actin and α-tubulin served as the internal control. All immunoblotting experiments were independently performed 3 times. The statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test [MDCK (A) and and 1-way ANOVA (B); HEK293T (A)]. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

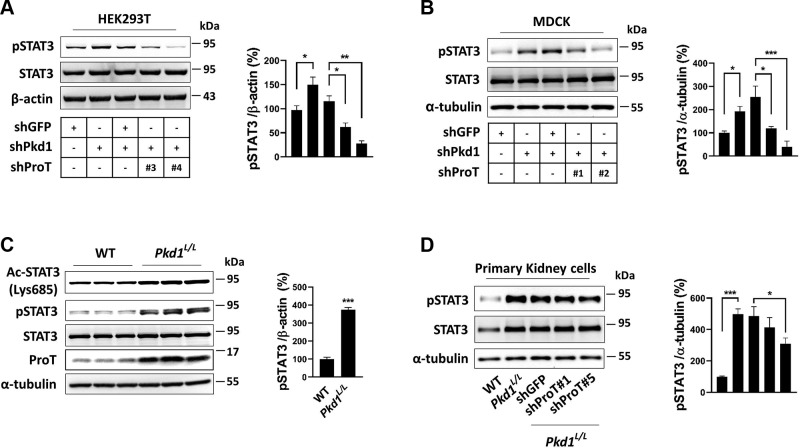

To further determine the critical role of ProT in STAT3 activation in PKD, we detected the level of activated STAT3 in Pkd1 low-expression cells in vitro and in vivo. Both MDCK and HEK293T cells with knockdown of Pkd1 showed an increase in STAT3 activation compared with the control group (shGFP) (Fig. 7A, B); additionally, Pkd1L/L kidney also displayed an increased level of STAT3 activation (Fig. 7C). We further suppressed the expression of ProT in Pkd1 knockdown cells (shPkd1/shProT), which lowered STAT3 activation compared with the suppression control (shPkd1/shGFP) in both cell lines (Fig. 7A, B). Using primary cells of Pkd1L/L kidney to further confirm, the results were consistent with those mentioned earlier; hyperactivation of STAT3 was obviously increased in Pkd1L/L cells, whereas knockdown of ProT by lentiviral transduction of shRNA in Pkd1L/L cells caused a decrease in STAT3 activation (Fig. 7D). Conclusively, our findings indicated that ProT is essential for STAT3 activation in Pkd1 low-expression cells both in vitro and in vivo; knockdown of ProT in Pkd1 low-expression cells is sufficient to suppress the activation of STAT3.

Figure 7.

ProT increased STAT3 activation in PKD. A, B) In the HEK293T (A) and MDCK (B) cell lines, knockdown of Pkd1 increased STAT3 activation (lanes 1 and 2), whereas simultaneous knockdown of ProT in the Pkd1-knockdown cells showed a reversed pattern compared with the knockdown control, shGFP (lanes 3, 4, and 5). The clones of shProT used were shProT#1 and #2 in MDCK and shProT#3 and #4 in HEK293T. C) Western blotting of activated STAT3 in WT and Pkd1L/L kidney protein lysates. Increased STAT3 activation was detected in the Pkd1L/L kidney. D) Detection of activation in primary kidney cells of WT or Pkd1L/L kidneys. The Pkd1L/L cells exhibited a greater amount of activated STAT3 than the WT cells (lanes 1 and 2), and suppression of ProT by lentiviral transfer of shProT in Pkd1L/L cells reduced the STAT3 activation compared with shGFP (lanes 3, 4, and 5). All immunoblotting experiments were independently performed 3 times. The statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test (C) and 1-way ANOVA (A, B, D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

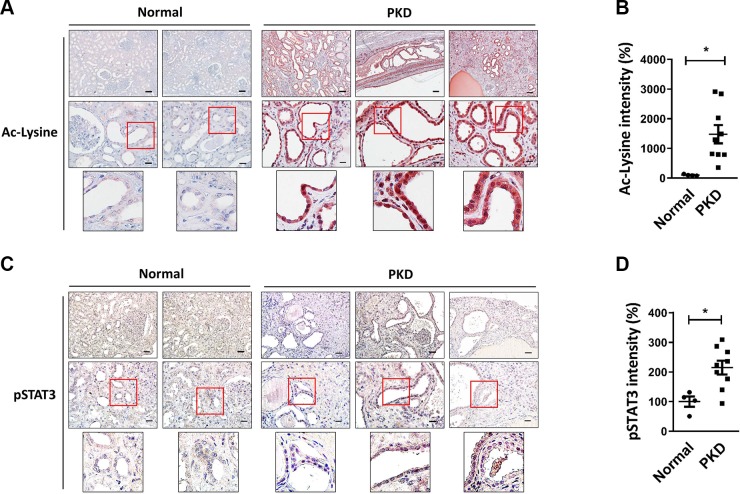

Protein acetylation and STAT3 activation in clinical samples

We dissected the molecular mechanisms of STAT3 activation in cell experiments, and finally, we further investigated the expression pattern of both acetylated protein and activated STAT3 in clinical samples. The results of the immunostaining assay showed the expression of acetylated protein to be significantly higher in PKD tissues than that in normal tissues (Fig. 8A); the statistical results were obtained by the quantification of relative color intensity (Fig. 8B). The expression of activated STAT3 also revealed a similar pattern; PKD tissues exhibited increased STAT3 activation compared with normal tissues (Fig. 8C), and the quantifying result was shown in Fig. 8D.

Figure 8.

The expression of protein acetylation and STAT3 activation in clinical samples. A, C) Immunostaining for acetyl-lysine (A) and activated STAT3 (phosphorylated Tyr705) (C). The photos are displayed at original magnifications, ×100 (left panel) and ×400 (medium panel). B, D) The quantification of staining intensity was measured by ImagePro Plus software and displayed as means ± sem. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Accumulated evidence shows that either gain-of-function or loss-of-function of polycystin-1 induces cystogenesis, and both models in kidneys indicate increased myc protein expression (22). ProT is one of the downstream myc proteins (32), supporting the importance of ProT in PKD. In this study, we demonstrate that ProT is involved in the Pkd1 signaling pathway and that it plays a pivotal role in cystogenesis. We further elucidate that ProT downstream increases protein acetylation, including STAT3 acetylation, which causes the activation of STAT3 and thus exaggerates cystogenesis.

Protein acetylation is mediated by acetyltransferase, whereas the reversed process is achieved by HDAC. The deacetylation of histone proteins leads to a condensed chromatin structure and transcriptional inactivation. Aside from altering chromatin structure, HDACs interact with various nonhistone proteins that affect a variety of cellular processes, including apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, and cell proliferation (33). Previous studies suggest that HDAC1 is responsible for p53 deacetylation and causes the p53-induced repression of Pkd1 gene transcription (34). Moreover, HDAC1 inhibitors, including trichostatin A and valproic acid, were shown to suppress kidney cyst formation in Pkd1 mutant mice (35). HDAC6, which promotes the deacetylation of α-tubulin during the normal cell cycle, is overexpressed in PKD, and suppressed HDAC6 expression increases the acetylation of α-tubulin and down-regulates EGFR expression in Pkd1 mutant renal epithelial cells (36, 37). Protein deacetylase sirtuin 1 involved in the pathophysiology of ADPKD is up-regulated in Pkd1-mutant renal epithelial cells, and inhibiting sirtuin 1 delays cyst growth in Pkd1-mutant kidneys (38). Despite the fact that HDAC inhibition leads to effective repression of cyst growth, the roles of protein acetylation in PKD still need to be investigated further.

Aberrant overexpression of ProT occurs in PKD, and it regulates a broad spectrum of protein acetylation in histone or nonhistone proteins by recruiting and stabilizing histone acetyltransferase (HAT) CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300 coactivators. In this study, we were unable to exclude the increased acetylation of other proteins that may take part in the progression of cyst development. However, disrupting STAT3 acetylation by exogenous expressing with STAT3 (K685R) mutant in ProT overexpressing MDCK cells actually improved the tubulogenesis in vitro (Supplemental Fig. S1), corroborating the pivotal role of STAT3 acetylation in cyst development. Additionally, we previously demonstrated that ProT up-regulated NF-κB acetylation and activation (19), and NF-κB is known to be activated in Pkd1-deficient kidneys (39). These results suggest ProT is also involved in NF-κB activation, thus contributing to the development of cystogenesis.

The phosphorylation in tyrosine 705 residue in STAT3 is responsible for its transactivation, whereas acetylated modification on Lys685 is also crucial for prolonging transcriptional activity (30). HDAC3 is classified as a member of the Type I HDAC family; the other members of the family are HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC4. HDAC1, HADC2, and HDAC3 are known to contribute to STAT3 deacetylation and to carry a homologous C-terminal region, which plays a regulatory role in HDAC catalytic activity. The C-terminal region of the above-mentioned HDACs has been demonstrated to interact with the N-terminal domain of STAT3 and deacetylate STAT3, resulting in a decrease in STAT3 activity (30). Our results depicted the interaction between STAT3 and HDAC3 under ProT overexpression conditions, and the expression of HDAC3 was not altered from the overexpression of ProT (19). Additionally, the result of binding between STAT3 and ProT corroborates a previous report indicating that ProT interacts with the N-terminal half of STAT3 and induces the translocation of STAT3 together with ProT from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (31). It therefore may be posited that ProT directly interacts with STAT3 and competitively inhibits its binding with HDAC3, which in turn causes STAT3 acetylation and prolonged activation.

STAT3 plays important roles in cell proliferation and differentiation. It is conceivable that cystic epithelial cells reveal undifferentiated and hyperproliferative properties that may be associated with aberrant activation of STAT3. It is uncertain whether the hyperactivation of STAT3 is the cause or effect of PKD progression despite the fact that previous studies have shown that constitutive activation of STAT3 in MDCK cells leads to a defective tubulogenesis (40). Several reports have shown that STAT3 is an effective target for amelioration of cyst growth, including curcumin, pyrimethamine, and S3I-201. All of these compounds have been found to improve cystogenesis by inhibiting STAT3 activation (23, 29, 41). Our results demonstrate that ProT up-regulates STAT3 activation both in vitro and in vivo and that cystogenesis induced by ProT overexpressing can be restored to the tubule phenotype by treating with STAT3 (K685R) mutation in vitro.

The activation of STAT3 in polycystin-1–based signaling has been mentioned in previous studies, where it was found that polycystin-1 interacts with JAK2 to induce STAT3 activation (42). Recent studies further stress its ability to induce STAT3 activation via the C-terminal tail of polycystin-1 (CTT) (43). CTT is ∼200 aa within the cytoplasmic region of polycystin-1, which goes through the proteolytic cleavage by γ-secretase and is subsequently released into cytosol (soluble CTT) (44). Similar to previous results obtained from stable transfection with full-length Pkd1 in cell experiments (42), it was found that membrane-anchored CTT is able to activate STAT3 through JAK2-dependent phosphorylation, whereas soluble CTT undergoing nuclear translocation is capable of enhancing the transcriptional activity of phosphorylated STAT3 (43). These results account for the accumulated soluble CTT contribution to the activation of STAT3 found in ADPKD kidney. In this study, we elucidate a novel mechanism suggesting that ProT increases STAT3 acetylation to promote STAT3 activation. It is unclear whether CTT in concert with ProT overexpression increases STAT3 activation, so we will further study the effect of ProT in CTT-based STAT3 activation in the future.

In summary, we obtained a molecular mechanism of ProT accelerating cyst progression, and we pointed out the augmentation of protein acetylation in PKD associated with the overexpression of ProT. These results suggest that ProT may be a potential therapeutic target for PKD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. A. B. Vartapetian (Belozersky Institute of Physico-Chemical Biology, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia) for generously providing the anti-ProT mAb (clone 2F11). The RNAi reagents were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility located at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genomic Research Center (Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan). This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) (103-2320-B-006-047-MY3 and 105-2320-B-006-038-MY3). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ADPKD

autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease

- CTT

C-terminal tail of polycystin-1

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HEK293T

human embryonic kidney 293T

- JAK

Janus kinase

- MDCK

Madin-Darby canine kidney

- PKD

polycystic kidney disease

- ProT

prothymosin α

- shGFP

small hairpin GFP

- shPKD

small hairpin PKD

- shProT

small hairpin ProT

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.-C. Chen, Y.-C. Su, B.-H. Su, and W.-C. Su performed the experiments and analyzed the data; G.-S. Shieh and P.-H. Huang collected clinical samples, performed the statistical analyses, and interpreted the data; S.-T. Jiang performed the animal study and interpreted the data; A.-L. Shiau designed the study, contributed to the discussion of the results, and edited the manuscript; Y.-C. Chen and C.-L. Wu wrote the manuscript; and C.-L. Wu is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris P. C., Torres V. E. (2009) Polycystic kidney disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 60, 321–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigro E. A., Castelli M., Boletta A. (2015) Role of the polycystins in cell migration, polarity, and tissue morphogenesis. Cells 4, 687–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma M., Gallagher A. R., Somlo S. (2017) Ciliary mechanisms of cyst formation in polycystic kidney disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avasthi P., Maser R. L., Tran P. V. (2017) Primary cilia in cystic kidney disease. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 60, 281–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko J. Y. (2016) Functional study of the primary cilia in ADPKD. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 933, 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu B., Li C., Liu Z., Dai Z., Tao Y. (2012) Increasing extracellular matrix collagen level and MMP activity induces cyst development in polycystic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 13, 109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghata J., Cowley B. D., Jr (2017) Polycystic kidney disease. Compr. Physiol. 7, 945–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Letsas K. P., Frangou-Lazaridis M. (2006) Surfing on prothymosin alpha proliferation and anti-apoptotic properties. Neoplasma 53, 92–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jou Y. C., Tsai Y. S., Hsieh H. Y., Chen S. Y., Tsai H. T., Chen K. J., Wang S. T., Shiau A. L., Wu C. L., Tzai T. S. (2013) Plasma thymosin-α1 level as a potential biomarker in urothelial and renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 31, 1806–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreira D., Díaz-Jullien C., Sarandeses C. S., Covelo G., Barbeito P., Freire M. (2013) The influence of phosphorylation of prothymosin α on its nuclear import and antiapoptotic activity. Biochem. Cell Biol. 91, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueda H., Matsunaga H., Uchida H., Ueda M. (2010) Prothymosin alpha as robustness molecule against ischemic stress to brain and retina. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1194, 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda H. (2009) Prothymosin alpha and cell death mode switch, a novel target for the prevention of cerebral ischemia-induced damage. Pharmacol. Ther. 123, 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez-Márquez J. (2007) Function of prothymosin alpha in chromatin decondensation and expression of thymosin beta-4 linked to angiogenesis and synaptic plasticity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1112, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subramanian C., Hasan S., Rowe M., Hottiger M., Orre R., Robertson E. S. (2002) Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C and prothymosin alpha interact with the p300 transcriptional coactivator at the CH1 and CH3/HAT domains and cooperate in regulation of transcription and histone acetylation. J. Virol. 76, 4699–4708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotter M. A., II Robertson E. S. (2000) Modulation of histone acetyltransferase activity through interaction of epstein-barr nuclear antigen 3C with prothymosin alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5722–5735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karetsou Z., Kretsovali A., Murphy C., Tsolas O., Papamarcaki T. (2002) Prothymosin alpha interacts with the CREB-binding protein and potentiates transcription. EMBO Rep. 3, 361–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi T., Wang T., Maezawa M., Kobayashi M., Ohnishi S., Hatanaka K., Hige S., Shimizu Y., Kato M., Asaka M., Tanaka J., Imamura M., Hasegawa K., Tanaka Y., Brachmann R. K. (2006) Overexpression of the oncoprotein prothymosin alpha triggers a p53 response that involves p53 acetylation. Cancer Res. 66, 3137–3144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su B. H., Tseng Y. L., Shieh G. S., Chen Y. C., Wu P., Shiau A. L., Wu C. L. (2016) Over-expression of prothymosin-α antagonizes TGFβ signalling to promote the development of emphysema. J. Pathol. 238, 412–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su B. H., Tseng Y. L., Shieh G. S., Chen Y. C., Shiang Y. C., Wu P., Li K. J., Yen T. H., Shiau A. L., Wu C. L. (2013) Prothymosin α overexpression contributes to the development of pulmonary emphysema. Nat. Commun. 4, 1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li K. J., Shiau A. L., Chiou Y. Y., Yo Y. T., Wu C. L. (2005) Transgenic overexpression of prothymosin alpha induces development of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 67, 1710–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trudel M., D’Agati V., Costantini F. (1991) C-myc as an inducer of polycystic kidney disease in transgenic mice. Kidney Int. 39, 665–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thivierge C., Kurbegovic A., Couillard M., Guillaume R., Coté O., Trudel M. (2006) Overexpression of PKD1 causes polycystic kidney disease. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 1538–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takakura A., Nelson E. A., Haque N., Humphreys B. D., Zandi-Nejad K., Frank D. A., Zhou J. (2011) Pyrimethamine inhibits adult polycystic kidney disease by modulating STAT signaling pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4143–4154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang S. T., Chiou Y. Y., Wang E., Lin H. K., Lin Y. T., Chi Y. C., Wang C. K., Tang M. J., Li H. (2006) Defining a link with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in mice with congenitally low expression of Pkd1. Am. J. Pathol. 168, 205–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos O. F., Moura L. A., Rosen E. M., Nigam S. K. (1993) Modulation of HGF-induced tubulogenesis and branching by multiple phosphorylation mechanisms. Dev. Biol. 159, 535–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima K., Yamanaka Y., Nakae K., Kojima H., Ichiba M., Kiuchi N., Kitaoka T., Fukada T., Hibi M., Hirano T. (1996) A central role for Stat3 in IL-6-induced regulation of growth and differentiation in M1 leukemia cells. EMBO J. 15, 3651–3658 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Battini L., Fedorova E., Macip S., Li X., Wilson P. D., Gusella G. L. (2006) Stable knockdown of polycystin-1 confers integrin-alpha2beta1-mediated anoikis resistance. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 3049–3058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sukhacheva E. A., Evstafieva A. G., Fateeva T. V., Shakulov V. R., Efimova N. A., Karapetian R. N., Rubtsov Y. P., Vartapetian A. B. (2002) Sensing prothymosin alpha origin, mutations and conformation with monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods 266, 185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonhard W. N., van der Wal A., Novalic Z., Kunnen S. J., Gansevoort R. T., Breuning M. H., de Heer E., Peters D. J. (2011) Curcumin inhibits cystogenesis by simultaneous interference of multiple signaling pathways: in vivo evidence from a Pkd1-deletion model. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 300, F1193–F1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan Z. L., Guan Y. J., Chatterjee D., Chin Y. E. (2005) Stat3 dimerization regulated by reversible acetylation of a single lysine residue. Science 307, 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C. H., Murti A., Baker S. J., Frangou-Lazaridis M., Vartapetian A. B., Murti K. G., Pfeffer L. M. (2004) Interferon induces the interaction of prothymosin-alpha with STAT3 and results in the nuclear translocation of the complex. Exp. Cell Res. 298, 197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eilers M., Schirm S., Bishop J. M. (1991) The MYC protein activates transcription of the alpha-prothymosin gene. EMBO J. 10, 133–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoo C. B., Jones P. A. (2006) Epigenetic therapy of cancer: past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 37–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Bodegom D., Saifudeen Z., Dipp S., Puri S., Magenheimer B. S., Calvet J. P., El-Dahr S. S. (2006) The polycystic kidney disease-1 gene is a target for p53-mediated transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31234–31244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y., Semanchik N., Lee S. H., Somlo S., Barbano P. E., Coifman R., Sun Z. (2009) Chemical modifier screen identifies HDAC inhibitors as suppressors of PKD models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21819–21824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pugacheva E. N., Jablonski S. A., Hartman T. R., Henske E. P., Golemis E. A. (2007) HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell 129, 1351–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu W., Fan L. X., Zhou X., Sweeney W. E., Jr., Avner E. D., Li X. (2012) HDAC6 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) endocytic trafficking and degradation in renal epithelial cells. PLoS One 7, e49418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou X., Fan L. X., Sweeney W. E., Jr., Denu J. M., Avner E. D., Li X. (2013) Sirtuin 1 inhibition delays cyst formation in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3084–3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin S., Taglienti M., Cai L., Zhou J., Kreidberg J. A. (2012) c-Met and NF-κB-dependent overexpression of Wnt7a and -7b and Pax2 promotes cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 1309–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon S. H., Nedvetsky P. I., Mostov K. E. (2011) Transcriptional profiling identifies TNS4 function in epithelial tubulogenesis. Curr. Biol. 21, 161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J., Lu D., Liu H., Williams B. O., Overbeek P. A., Lee B., Zheng L., Yang T. (2017) Sclt1 deficiency causes cystic kidney by activating ERK and STAT3 signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 2949–2960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhunia A. K., Piontek K., Boletta A., Liu L., Qian F., Xu P. N., Germino F. J., Germino G. G. (2002) PKD1 induces p21(waf1) and regulation of the cell cycle via direct activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a process requiring PKD2. Cell 109, 157–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Talbot J. J., Shillingford J. M., Vasanth S., Doerr N., Mukherjee S., Kinter M. T., Watnick T., Weimbs T. (2011) Polycystin-1 regulates STAT activity by a dual mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7985–7990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merrick D., Chapin H., Baggs J. E., Yu Z., Somlo S., Sun Z., Hogenesch J. B., Caplan M. J. (2012) The γ-secretase cleavage product of polycystin-1 regulates TCF and CHOP-mediated transcriptional activation through a p300-dependent mechanism. Dev. Cell 22, 197–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.