Abstract

We recently reported that membrane potential (ΔΨ) primarily determines the relationship of complex II–supported respiration by isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria to ADP concentrations. We observed that O2 flux peaked at low ADP concentration ([ADP]) (high ΔΨ) before declining at higher [ADP] (low ΔΨ). The decline resulted from oxaloacetate (OAA) accumulation and inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase. This prompted us to question the effect of incremental [ADP] on respiration in interscapular brown adipose tissue (IBAT) mitochondria, wherein ΔΨ is intrinsically low because of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). We found that succinate-energized IBAT mitochondria, even in the absence of ADP, accumulate OAA and manifest limited respiration, similar to muscle mitochondria at high [ADP]. This could be prevented by guanosine 5′-diphosphate inhibition of UCP1. NAD+ cycling with NADH requires complex I electron flow and is needed to form OAA. Therefore, to assess the role of electron transit, we perturbed flow using a small molecule, N1-(3-acetamidophenyl)-N2-(2-(4-methyl-2-(p-tolyl)thiazol-5-yl)ethyl)oxalamide. We observed decreased OAA, increased NADH/NAD+, and increased succinate-supported mitochondrial respiration under conditions of low ΔΨ (IBAT) but not high ΔΨ (heart). In summary, complex II–energized respiration in IBAT mitochondria is tempered by complex I–derived OAA in a manner dependent on UCP1. These dynamics depend on electron transit in complex I.—Fink, B. D., Yu, L., Sivitz, W. I. Modulation of complex II–energized respiration in muscle, heart, and brown adipose mitochondria by oxaloacetate and complex I electron flow.

Keywords: mitochondrial respiratory chain, brown adipose tissue, succinate dehydrogenase, S1QEL 1.1

We recently reported a previously unrecognized mitochondrial respiratory phenomenon (1). When [ADP] was clamped at sequentially increasing concentrations in succinate-energized skeletal muscle mitochondria (in the absence of rotenone commonly added to inhibit complex I), we observed a biphasic increasing-then-decreasing respiratory response. O2 flux peaked at low [ADP] before declining at higher [ADP].

More recently, we reported that the mechanism underlying this phenomenon consisted of a sequence of events initiated by altered membrane potential (ΔΨ) and culminating in the accumulation of oxaloacetate (OAA) and OAA inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) (2). The sequence is as follows: Increments in [ADP] cause decrements in ΔΨ. These decrements decrease reverse electron transport (RET) from complex II to complex I, which is otherwise substantial in complex II–energized mitochondria. RET maintains complex I NADH in the reduced state (3, 4), but as RET is reduced, NADH cycling with NAD+ is enabled, allowing the conversion of malate to OAA in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. OAA can then inhibit SDH at complex II. So, at low [ADP] (high ΔΨ), OAA does not form, and initial increments in [ADP] (decrements in ΔΨ) increase succinate-energized respiration. However, once ΔΨ is decreased enough, OAA accumulation begins to decrease complex II–initiated respiration, accounting for the biphasic nature of succinate-energized respiration as a function of [ADP]. A point to emphasize is that only small concentrations of OAA are needed to inhibit SDH; hence, only a mild rightward shift in the kinetically leftward-directed malate dehydrogenase reaction generates sufficient OAA to inhibit SDH.

We were unable to find any prior description of this biphasic respiratory pattern. We believe the reasons for this were as follows: First, most past studies of respiration by isolated mitochondria were carried out in the presence of large amounts of ADP (state 3 respiration) or in the absence of ADP (state 4) rather than at intermediate concentrations. Mitochondria in vivo do not function at either extreme but, rather, in between (5). Second, a large portion of early studies of mitochondrial metabolism used liver mitochondria, wherein we found that this biphasic succinate-energized effect is barely evident (1). And third, it has become common practice to carry out studies of succinate-energized respiration in the presence of rotenone, which obviates RET (3, 6).

Prior studies done decades ago did show that OAA inhibits SDH (7–13). However, the phenomenon has been largely neglected. We believe this is because OAA is unstable and difficult to quantify by mass spectroscopy or other means (14, 15). In our past work (1, 2) and in this current study, we used a sensitive and highly specific NMR method to quantify OAA. Another reason the effect of OAA has not received attention again involves the use of rotenone to block electron flow through complex I. But rotenone also blocks malate conversion to OAA, thus obscuring any feedback effect of OAA to inhibit complex II.

Our results implied that the primary initiating factor responsible for the sequential effect of [ADP] to temper respiration through OAA inhibition is the progressive drop in inner mitochondrial ΔΨ, as ΔΨ is consumed to generate ATP. In support of this, the effect of ADP titration on respiration could be mimicked by titrating with the chemical uncouplers trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone or 2,4-dinitrophenol (2).

Here, we extended our studies to mouse heart and interscapular brown adipose tissue (IBAT) mitochondria. Because of the primary role of reduced ΔΨ in initiating events leading to OAA accumulation, our major interest was in IBAT mitochondria, wherein ΔΨ is intrinsically low because of abundant uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). Our major hypothesis was that succinate-energized respiration in IBAT, even at 0 or low [ADP], would be limited by UCP1-mediated low ΔΨ and consequent OAA inhibition of SDH. On the other hand, we hypothesized that succinate-energized respiration by heart mitochondria (which are not subject to uncoupling and maintain high ΔΨ at low ADP) would mirror the pattern seen in skeletal muscle. Moreover, because altered complex I electron flow is critical to the mechanism underlying the biphasic nature of succinate-energized respiration vs. [ADP] in muscle, we reasoned that alteration of complex I electron flow would change this pattern. We also reasoned that altered electron flow would perturb the effect of UCP1-mediated low ΔΨ on respiration in IBAT mitochondria. To assess these questions, we used a small molecule termed N1-(3-acetamidophenyl)-N2-(2-(4-methyl-2-(p-tolyl)thiazol-5-yl)ethyl)oxalamide (S1QEL 1.1), reasoning that its interaction with complex I would affect electron flow. S1QEL 1.1 affects events at the Iq or quinone binding site of complex I (16, 17). Moreover, the compound was recently shown to interact with the ND1 subunit apart from, but in a way that may modulate, the quinone binding site (18).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and supplies

2-Cyano-3-(1-phenylindol-3-yl)prop-2-enoic acid (UK5099), ADP, and OAA were obtained from MilliporeSigma (Burlington, MA, USA). According to the manufacturer, ADP was 99.5% pure. [13C]4-succinate was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA, USA). S1QEL 1.1 was purchased from Life Chemicals (Woodbridge, CT, USA). Otherwise, reagents, kits, and supplies were as specified or purchased from standard sources.

Animal procedures

Animals were maintained according to National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) guidelines, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Iowa–Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Male C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were fed a normal rodent diet (13% kcal fat) (Diet 7001, Teklad; Envigo, Huntingdon, United Kingdom) until euthanasia at age 5–9 wk. Mice were euthanized by isoflurane overdose and cardiac puncture.

Preparation of mitochondria

Mitochondria were prepared by differential centrifugation with further purification on a Percoll gradient as we have previously described (19). Mitochondrial integrity was assessed by cytochrome C release using a commercial kit (Cytochrome c Oxidase Assay Kit; MilliporeSigma), indicating a mean of 96% intact mitochondria over 3 assays, well within an acceptable range compared with mitochondrial preparations from several sources (20).

Respiration and ΔΨ

All studies of mitochondrial respiration and inner ΔΨ utilized freshly isolated and purified mitochondria on the day of preparation. Respiration was determined using an Oxygraph-2k High-Resolution Respirometer (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). In experiments wherein ΔΨ was also measured, this was carried out simultaneously with respiration using a potential sensitive tetraphenylphosphonium electrode fitted into the oxygraph incubation chamber. A tetraphenylphosphonium standard curve was performed in each run by adding tetraphenylphosphonium chloride at concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 μM prior to the addition of mitochondria to the chamber. Mitochondria (0.1 mg/ml) were incubated at 37°C in 2 ml of ionic respiratory buffer [105 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 1 mM EGTA, 0.2% defatted bovine serum albumin] with 5 U/ml hexokinase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, USA) and 5 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2DOG).

In all experiments, ADP was clamped at the desired concentration. In some experiments, ADP was incrementally added to achieve desired sequential clamped concentrations, with plateaus in respiration and potential achieved after each addition. In other experiments, ADP was maintained at a constant level throughout the 20-min incubation time. Although the O2 tension in the oxygraph drops with time, respiration is not affected until levels become very low. However, because incubations were carried out for 20 min, it was necessary to open the chamber at one point to prevent marked deterioration in the oxygen content of the medium. Representative oxygraph tracings are shown in Supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

ADP recycling and generation of the 2DOG ATP energy clamp

We used a method we previously developed to carry out bioenergetic studies of isolated mitochondria under conditions of clamped ADP and ΔΨ (19, 21). Mitochondrial incubations were carried out in the presence of hexokinase, excess 2DOG, and varying amounts of added ADP. ATP generated from ADP under these conditions drives the conversion of 2DOG to 2DOG phosphate while regenerating ADP. The reaction occurs rapidly and irreversibly, thereby effectively clamping ΔΨ determined by available ADP. This was in fact the case, as we have demonstrated in the past for rat and mouse muscle (2, 21), mouse liver (22), and mouse heart (22) mitochondria.

Immunocapture and activity of SDH

SDH activity was determined using a kit designed for determining complex II activity in human, mouse, rat, or bovine samples (Complex II Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit, ab109908; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Detergent extracts were prepared from mouse hind limb muscle mitochondria previously frozen at −80°C in the presence of Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). SDH was captured in wells coated with mAb directed at complex II. Enzyme-driven production of ubiquinol coupled to the reduction of the dye 2,6-diclorophenolindophenol was monitored as the rate of decrease in absorbance at 600 nm (ΔA600) in milli–optical density units per minute over the linear range from 10 to 50 min.

Metabolite measurements

Metabolite measurements by NMR spectroscopy were carried out as previously described (1, 2) on the contents of the oxygraph chamber after mitochondrial incubation with 10 mM [13C]4-succinate as substrate, hence the same media used for measuring respiration. Immediately after mitochondrial incubations, 1.5 ml of the chamber content was placed in tubes on ice and acidified with 91 µl of 70% perchloric acid. The solutions were then thoroughly mixed, sonicated on ice for 30 s at a power setting of 4 W, and then stored at −80°C for up to 2 wk. The sample tubes were then thawed on ice and centrifuged at 50,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatants were removed from the centrifuge tube and 10 N KOH was added to bring the solution pH to 7.4, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 15 min at 4°C to remove precipitated salts. The cleared, neutralized supernatants were then stored at −80°C prior to NMR studies. For NMR sample preparations, 350 µl of the stored supernatant was added to 150 µl of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, in deuterium oxide for metabolite measurement. [13C] and [1H] NMR assignments of succinate, malate, fumarate, OAA, and citrate were obtained by using standard compounds. OAA was found to be unstable, with a half-life of about 14 h when tested at pH 7.4 and temperature at 25°C. Therefore, after mitochondrial incubation, perchloric acid extraction was carried out as quickly as possible to destroy the mitochondrial enzymes and minimize the degradation of OAA. In addition, for determination of stability, known amounts of OAA were subjected to parallel incubation, perchloric acid extraction, neutralization, and storage.

Both [13C]/[1H] heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) and heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC) spectra were collected at 25°C on a Bruker Avance II 800 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a sensitive cryoprobe for the perchloric acid–extracted samples for quantification of metabolites of the mitochondrial incubations. All NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe package (23) and analyzed using NMRView (24). Peak heights were used for quantification.

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production as hydrogen peroxide or superoxide

Mitochondria were incubated in microplate wells with shaking for 20 min in ionic respiratory buffer, mimicking the conditions utilized for our oxygraph incubation. H2O2 production was assessed as we have previously described (19) using the fluorescent probe 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (Amplex Red; Thermo Fisher Scientific), a highly sensitive and stable substrate for horseradish peroxidase and a well-established probe for isolated mitochondria (25). Fluorescence was measured, and quantification was carried out as we previously described (6).

Quantification of NADH and NAD+

The redox state of mitochondrial NAD was measured using a commercially available NAD+/NADH Assay Kit G9071 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Samples were taken directly from the oxygraph chamber after 20-min incubations to determine respiration. Duplicate 50-μl aliquots of the chamber contents were processed with either acid or base according to the instructions of the kit protocol for separate measurements of NAD+ and NADH.

Statistics

Data were analyzed as indicated in the figure legends using Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Significance was considered at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

ADP-dependent, succinate-energized respiratory function in heart mitochondria

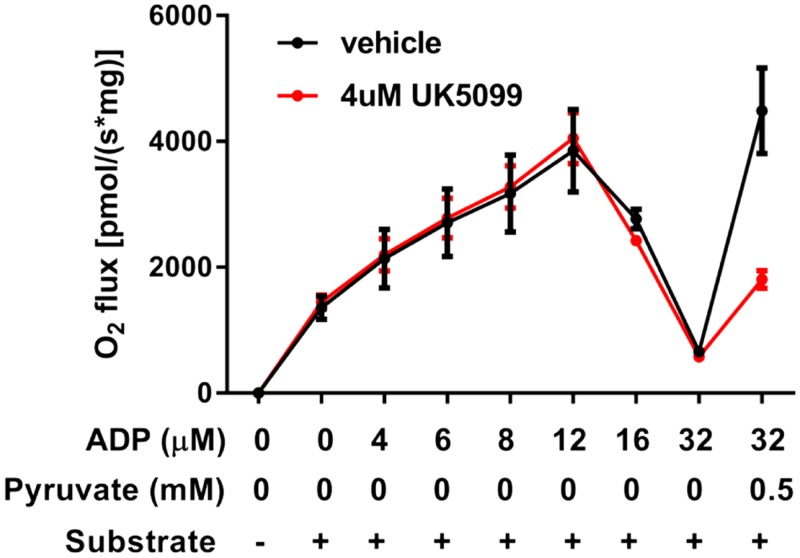

We observed a biphasic increasing-then-decreasing respiratory response to incremental clamped concentrations of ADP in succinate-energized heart mitochondria (Fig. 1), similar to what we previously reported for skeletal muscle (2). When [ADP] reached 32 µM, a low concentration of pyruvate was added to clear OAA to citrate. As expected, pyruvate markedly increased O2 flux. This effect of pyruvate was blunted in the presence of UK5099, a well-established inhibitor of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (26). Note that UK5099 had no effect on respiration prior to the addition of pyruvate. The biphasic respiratory response in Fig. 1 was not related to time of incubation or deterioration of mitochondrial function over time. As we showed in the past for muscle mitochondria (1), direct incrementation of ADP from 0 to 32 µM ADP resulted in a rapid loss of respiratory function after a very brief increase, likely because of an initial transient response to rising [ADP] before suppression at 32 μM (Supplemental Fig. S3). Moreover, the rapid response to pyruvate in Fig. 1 would not be expected had mitochondria became impaired over time.

Figure 1.

Respiratory response of heart mitochondria to incremental additions of ADP. Mitochondria were energized by succinate (10 mM) and incubated with sequentially increasing clamped concentrations of ADP. A low concentration of pyruvate (0.5 mM) was added at an ADP concentration of 32 µM. Incubations were carried out in the presence (n = 2) or absence (n = 2) of UK5099, a specific inhibitor of the pyruvate carrier. Data represent means ± sem.

ADP-dependent, succinate-energized respiratory function in IBAT mitochondria

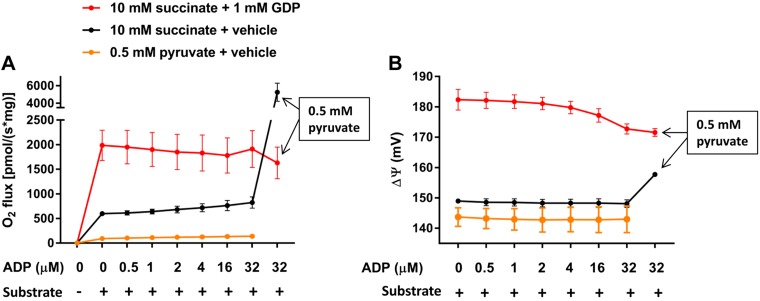

Given the primary role of ΔΨ in initiating the drop in RET and consequent OAA-inhibited respiration in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria, we questioned the effect of sequentially increasing [ADP] in IBAT mitochondria wherein inner ΔΨ is intrinsically low due to the activity of UCP1. As shown in Fig. 2A, sequential additions of ADP had little effect on succinate-driven O2 flux. However, the addition of a low-concentration pyruvate (to clear OAA to citrate) when the concentration of ADP reached 32 µM markedly increased respiration. Pyruvate alone as substrate at that concentration had almost no effect on respiration. When incubations were done in the presence of guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP) to inhibit UCP1 activity, respiration was markedly enhanced, associated with increased ΔΨ (Fig. 2B), but unaffected by adding pyruvate.

Figure 2.

Respiration and ΔΨ in IBAT mitochondria incubated with incremental additions of ADP and energized by succinate (10 mM) or pyruvate (0.5 mM) as indicated and in the presence of 1 mM GDP or vehicle (water). Substrate (succinate or pyruvate) was added prior to incremental additions of ADP. For succinate-energized incubations, pyruvate (0.5 mM) was added at an ADP concentration of 32 µM (boxed text). A) O2 flux in the presence or absence of 1 mM GDP (n = 3). B) Inner membrane ΔΨ in the presence or absence of 1 mM GDP (n = 2). Data represent means ± sem.

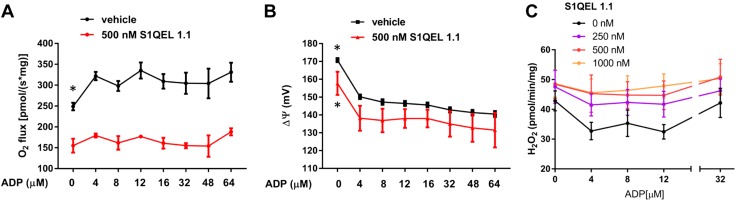

Effect of S1QEL 1.1 on ADP-dependent, succinate-energized respiratory function in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria

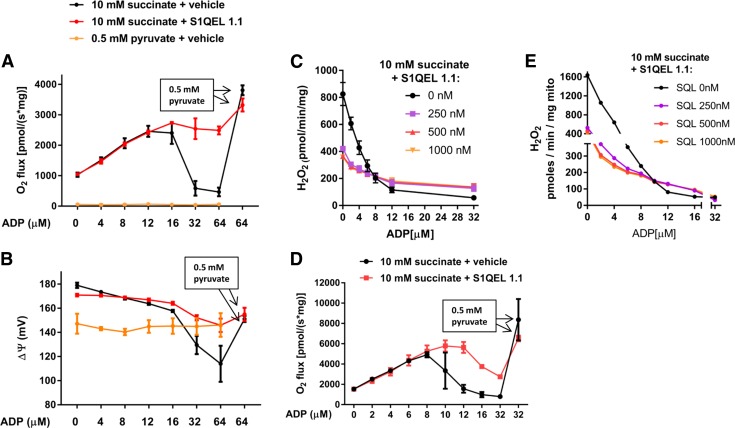

The mechanism leading to OAA accumulation in succinate-energized mitochondria incudes enabling of NADH and NAD+ cycling and, thus, involves electron flow through the flavin (IF) site of complex I. S1QEL 1.1 acts at the Iq site and impairs the transfer of electrons to molecular oxygen. Hence, we speculated that S1QEL 1.1 might generate electron back pressure to the IF site, impairing NADH/NAD+ cycling. If so, that would impair OAA accumulation and block the ADP-dependent downturn in respiration (as seen in the relationship of respiration to [ADP] in Fig. 1). Therefore, we examined O2 flux, membrane potential, and H2O2 production in succinate-energized heart and muscle mitochondria incubated at sequentially increasing [ADP] in the presence of S1QEL 1.1 or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) (Fig. 3). Indeed, S1QEL 1.1 enhanced heart and skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration, but only after ADP reached concentrations resulting in peak O2 flux (Fig. 3A, D). In other words, S1QEL 1.1 mitigated the downturn in respiration. ΔΨ, measured in heart mitochondria, dropped sharply at that point in the absence of S1QEL 1.1 (Fig. 3B). A low concentration (0.5 mM) of pyruvate, added at an ADP concentration of 64 μM, markedly increased respiration in the absence of S1QEL 1.1, consistent with clearance of OAA (Fig. 3A, D). Note that pyruvate, at that low concentration, had almost no effect on respiration when used as the only energy substrate (Fig. 3A). As expected, S1QEL 1.1 decreased H2O2 production (Fig. 3C, E) at low concentrations of ADP. However, H2O2 production at higher concentrations of ADP was greater in the presence than in the absence of S1QEL 1.1.

Figure 3.

Effect of S1QEL 1.1 on mitochondrial functional parameters in heart and hind limb skeletal muscle mitochondria energized as indicated. A) O2 flux in heart mitochondria incubated at incremental clamped concentrations of ADP in the presence or absence of S1QEL 1.1 (500 nM). A low concentration of pyruvate (0.5 mM) was added at 64 μM ADP (boxed text). B) ΔΨ determined simultaneously with O2 flux in the mitochondria of A. C) H2O2 production by heart mitochondria incubated at incremental clamped concentrations of ADP in the presence or absence of variable amounts of S1QEL 1.1. D) O2 flux in skeletal muscle mitochondria incubated at incremental clamped concentrations of ADP in the presence or absence of S1QEL 1.1 (500 nM). A low concentration of pyruvate (0.5 mM) was added at 32 μM ADP. E) H2O2 production by muscle mitochondria incubated at incremental clamped concentrations of ADP in the presence or absence of variable amounts of S1QEL 1.1. Data represent means ± sem; n = 3 for each data point (A–C), and n = 2 for each data point (D, E).

Metabolite accumulation and effect of S1QEL 1.1 in succinate-energized IBAT and heart mitochondria at low [ADP]

The data listed in Table 1 address 2 issues. First, the experiments expand on the data depicted in Fig. 2, which show that pyruvate markedly increased respiration in IBAT mitochondria (in the absence of GDP), whereas ADP had minimal, if any, effect to increase respiration. This suggests that OAA accumulates in succinate-energized IBAT mitochondria even in the absence of added ADP. On the other hand, we reasoned that OAA would not accumulate in heart mitochondria in the absence of ADP, because ΔΨ is high in heart mitochondria under these conditions, whereas ΔΨ is intrinsically low in IBAT mitochondria. Therefore, we incubated both IBAT and heart mitochondria for 20 min without ADP, allowing time for metabolite accumulation. As shown in Table 1, under these conditions, OAA accumulated in IBAT but not heart mitochondria.

TABLE 1.

Parameters measured in IBAT and heart mitochondria energized with 10 mM succinate and incubated for 20 min

| Parameter | IBAT mitochondria |

Heart mitochondria |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | S1QEL 1.1 | P | Control | S1QEL 1.1 | P | |

| O2 flux (nmol O2/mg) | 513 ± 17 | 1056 ± 39 | <0.0001 | 2007 ± 193 | 1903 ± 155 | NS |

| ΔΨ (mV) | 123 ± 6 | 135 ± 8 | NS | 184 ± 3 | 184 ± 6 | NS |

| NADH (pmol/mg) | 404 ± 155 | 2382 ± 276 | <0.001 | 1204 ± 165 | 1725 ± 118 | 0.042 |

| NAD+ (pmol/mg) | 9377 ± 364 | 7742 ± 581 | 0.05 | 5424 ± 386 | 5014 ± 321 | NS |

| NADH/NAD+ | 0.044 ± 0.018 | 0.311 ± 0.041 | <0.001 | 0.220 ± 0.018 | 0.347 ± 0.025 | <0.01 |

| OAA (µM) | 1.85 ± 0.29 | 0 ± 0 | <0.001 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | ND |

| Citrate (µM) | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | ND | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | ND |

| Succinate (mM) | 9.63 ± 0.13 | 9.44 ± 0.11 | NS | 9.22 ± 0.19 | 9.07 ± 0.13 | NS |

| Malate (µM) | 134 ± 5 | 299 ± 11 | <0.0001 | 611 ± 69 | 594 ± 44 | NS |

| Fumarate (µM) | 11.1 ± 1.5 | 18.7 ± 2.3 | 0.031 | 25.2 ± 2.1 | 23.2 ± 2.9 | NS |

Incubations were done in the presence of S1QEL 1.1 or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). Respiration represents the area under the curve for O2 flux over time, and ΔΨ represents the mean potential over time. The remaining parameters were assessed in the incubation media at the 20-min time point. n = 4 for all parameters. ADP was not present in any of these incubations. P values determined by 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t tests. ND, not done; NS, not significant.

Second, the studies shown in Table 1 address the effect of S1QEL 1.1 in IBAT and heart mitochondria in the absence of ADP. We hypothesized, as previously mentioned, that if S1QEL 1.1 retarded electron flux through the IF site of complex I, the compound should maintain NADH in the reduced state, increasing the NADH/NAD+ ratio, lowering OAA, and enhancing respiration. As shown in Table 1, this was indeed observed for IBAT mitochondria wherein ΔΨ is intrinsically low. However, consistent with the high ΔΨ in the absence of ADP, this was not the case for heart mitochondria, except for a mild increase in NADH and in the NADH/NAD+ ratio. The changes in ΔΨ, citrate, malate, and fumarate (Table 1) are consistent with the effect of S1QEL 1.1 on respiration in IBAT mitochondria, whereas the lack of change of these parameters in heart mitochondria is consistent with the lack of change in respiration in these mitochondria.

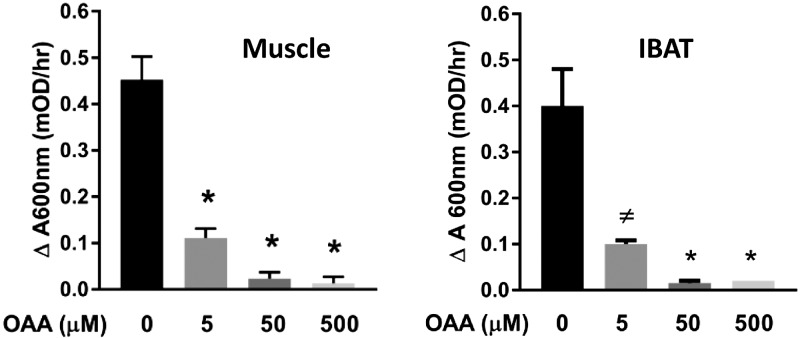

Inhibition of IBAT SDH by OAA

To verify that OAA can inhibit SDH in IBAT mitochondria, as we had previously confirmed in skeletal muscle mitochondria, we assessed the effect of OAA on SDH activity in extracts of IBAT mitochondria (Fig. 4). As expected, OAA strongly inhibited IBAT SDH.

Figure 4.

Effect of OAA on SDH activity in extracts of mouse skeletal muscle and IBAT mitochondria. The data for muscle mitochondria were previously published (2), but are shown here for comparison to IBAT activity; n = 4 for all data points, except n = 3 for IBAT at 500 µM OAA. *P < 0.001, ≠P = 0.001 compared with 0 OAA by 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to control (OAA = 0 µM).

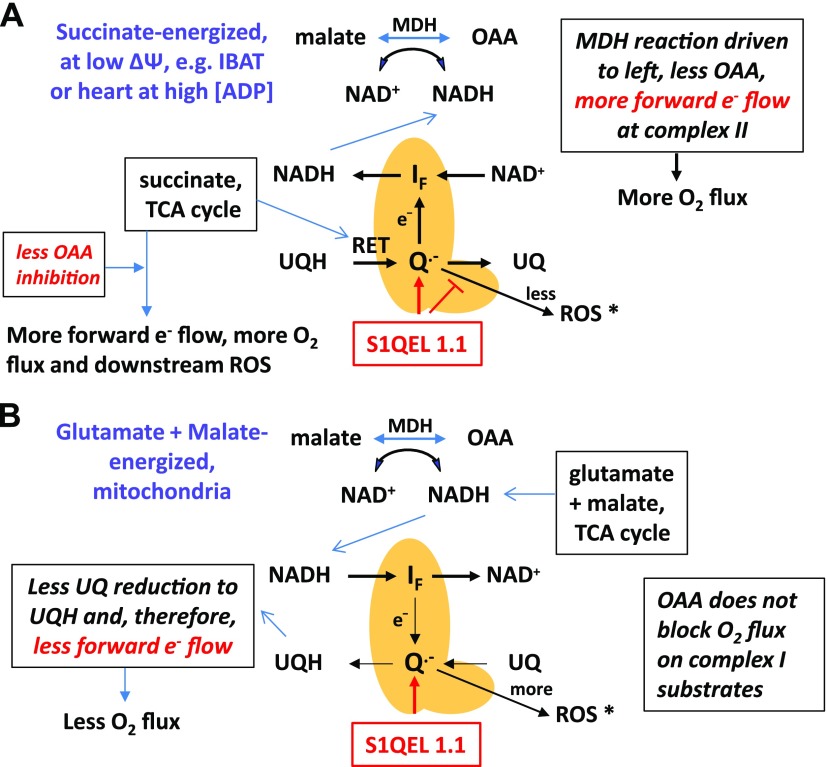

Effect of S1QEL 1.1 on ADP-dependent, glutamate plus malate–energized respiratory function in heart mitochondria

The above effects of S1QEL 1.1 on electron flow were observed under conditions of succinate-generated RET. Hence, this led us to question what might be observed under conditions of forward transport through complex I. Therefore, we also examined respiration, ΔΨ, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production at incremental clamped ADP concentrations in heart mitochondria energized by the complex I substrates, glutamate plus malate, in the presence of S1QEL 1.1 or vehicle (Fig. 5). In the presence of vehicle, respiration increased when ADP was added at 4 µM (compared with the absence of ADP) but changed little with subsequent increments in [ADP] (Fig. 5A). In contrast to what we observed for succinate-energized heart mitochondria, S1QEL 1.1 decreased respiration. ΔΨ also decreased with additions of ADP in the presence or absence of S1QEL 1.1 but was lower in the presence of the compound (Fig. 5B). Most of the drop in potential occurred by an ADP concentration of 4 µM, suggesting that near maximal (state 3 respiration) was achieved at that point. Also, in contrast to succinate-energized heart mitochondria, S1QEL 1.1 increased ROS production at all levels of ADP (Fig. 5C). Overall, at any concentration of S1QEL 1.1, ROS production in these glutamate plus malate–energized mitochondria was substantially less than in succinate-energized mitochondria (compare Figs. 5C with 3C, E).

Figure 5.

Effect of S1QEL 1.1 or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) on mitochondrial respiration, ΔΨ, and ROS in heart mitochondria energized with glutamate (10 mM) plus malate (2 mM). A) O2 flux. B) Potential. C) H2O2 production. Data represent means ± sem; n = 3 for all data points. *P < 0.05 compared with O2 flux at 4 µM ADP by 1-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons to control (0 ADP).

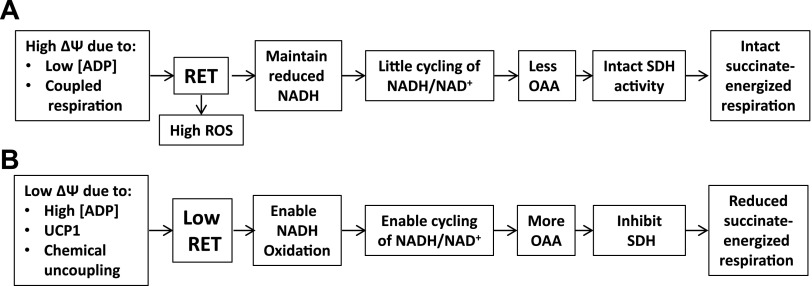

DISCUSSION

Our present and past (1, 2) data provide novel insight into the interrelations of ΔΨ, directional electron flow in complex I, and the rate of mitochondrial respiration in IBAT, muscle, and heart. In each tissue, low ΔΨ, either caused by ADP in muscle and heart or by uncoupling in IBAT, leads to OAA inhibition of complex II–supported mitochondrial respiration. Figure 6 summarizes events at high and low ΔΨ as implicated by our past (1, 2) and now current data in muscle, heart, and IBAT mitochondria.

Figure 6.

Sequence of events depicting the effect of high (A) and low (B) ΔΨ on succinate-energized (complex II) respiration.

Given metabolic commonalities between cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle myocytes, it is not surprising that we observed a similar biphasic response of respiration to [ADP] in heart mitochondria (Fig. 1), as we had reported for muscle mitochondria (1, 2). For heart, like skeletal muscle, the decrease in respiration at high [ADP] was rapidly reversed by addition of pyruvate (Fig. 1) to clear OAA to citrate.

In IBAT mitochondria, the dynamics of respiration vs. [ADP] differed from muscle and heart. For IBAT, our results (Fig. 2) show that succinate-energized respiration, even at 0 or low [ADP], resembles that for heart or muscle mitochondria at higher [ADP]. In other words, the intrinsic low ΔΨ of IBAT, even at low [ADP], due to UCP1 mimics the low potential created by high [ADP] in heart or muscle mitochondria and limits respiration. Pyruvate, at a concentration that had barely any effect on respiration when used alone as substrate, markedly enhanced succinate-energized respiration, strongly suggesting that this occurs through clearance of OAA to citrate and supporting the concept of OAA inhibition of SDH and limitation of O2 flux. We could find no prior reports describing the above dynamics. We point out that the pyruvate-induced increase in respiration (Fig. 2A) was associated with only a small increase in ΔΨ that did not reach levels in the GDP-inhibited mitochondria (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with restoration of the normal uncoupled state of IBAT mitochondria.

The effect of UCP1 to regulate respiration in these succinate-energized IBAT mitochondria was demonstrated by the effect of GDP (Fig. 2A), a well-established inhibitor of UCP1. In the presence of GDP, respiration and ΔΨ were increased substantially, even before the addition of ADP, resembling what we observed for heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria at low [ADP] (wherein ΔΨ is high). Moreover, in the presence of GDP, when a low concentration of pyruvate was added to clear OAA, respiration did not increase. This contrasts markedly to the effect of the low concentration of pyruvate in the absence of GDP. We interpret this as follows: In the absence of GDP, ΔΨ is low because of UCP1, so OAA accumulates and inhibits respiration. But when pyruvate is added to clear OAA, the classic effect of UCP1 can now take hold, and respiration increases. In the presence of GDP, ΔΨ is high, OAA is not present, and UCP1 is inactive, so there is no pyruvate effect because there is no OAA to clear.

Hence, our data imply that succinate-energized IBAT mitochondria are prone to OAA accumulation and inhibition of SDH even in the absence of ADP. This interpretation was further examined by assessing metabolic parameters in succinate-energized IBAT and heart mitochondria incubated without ADP addition. The data in Table 1 are mainly intended to show the effect of S1QEL 1.1, but it is clear from the table that OAA accumulated in succinate-energized IBAT mitochondria but not heart mitochondria.

S1QEL 1.1 is a small molecule (MW 437) that was identified through a molecular screening process designed to assess ROS production at specific sites within the mitochondrial electron transport system (16, 17, 27). The compound was found to block ROS production at the Iq or quinone binding site of complex I during RET. Because we thought that S1QEL 1.1 would alter electron flow in complex I, we hypothesized that the compound would prevent the downturn in succinate-energized respiration as [ADP] is increased. As shown in Fig. 3, the downturn in respiration was indeed prevented or mitigated in muscle and heart mitochondria once [ADP] was sufficiently incremented. As expected, S1QEL 1.1 decreased ROS production at low [ADP] when RET was very active. However, S1QEL 1.1 actually increased ROS at high [ADP] when RET was low due to reduced potential. We believe that the increase in ROS in this circumstance is simply because of the increase in complex II respiration and ROS production at sites other than the Iq site of complex I.

We then questioned what would occur in IBAT mitochondria in the absence of ADP if electron flow were perturbed by S1QEL 1.1. To do this, we monitored respiration and ΔΨ in succinate-energized mitochondria with or without S1QEL 1.1 for 20 min (enough time to allow perturbations in adenine dinucleotides and accumulation of metabolites). As shown in Table 1, OAA was undetectable in the presence of S1QEL 1.1, whereas respiration was increased. Moreover, the NADH/NAD+ redox state was substantially more reduced in the presence of S1QEL 1.1. This would drive the malate dehydrogenase reaction more to the left, thus decreasing OAA and accounting for the increase in respiration. Note that citrate was not increased by S1QEL 1.1 as occurs with pyruvate (2), because, rather than clear OAA to citrate, S1QEL 1.1 prevented the formation of OAA. Also, note that the change in the redox state of NADH/NAD+ as well as the effect of S1QEL 1.1 on OAA and malate suggest that the compound did alter electron flow in complex I.

Although these data suggest that S1QEL 1.1 alters electron flow toward the IF site, more work is needed to prove how this occurs. Nonetheless, we can offer a plausible, but speculative, explanation, as depicted in Fig. 7A. We suggest that during respiration, energized by succinate, S1QEL 1.1 either directly or indirectly affects electron transit at the IQ site in a way that favors reverse flow toward the IF site. Conceivably, this might involve a shortened lifetime of the intermediate semiquinone that leaks electrons while ubiquinol and ubiquinone are intraconverted (3, 28). This scenario might induce less ROS while enabling more backflow of electrons originating in complex II, thereby inducing a more reduced NADH/NAD+ state, less OAA, and greater respiration. This scenario is compatible with the data in Table 1. Although ROS is actually greater on succinate-energized respiration at high [ADP] (Fig. 3C, E), that does not contradict the postulated events in Fig. 7A. This is because at high ADP, forward electron transport from complex II to complex III is greater, likely generating more ROS at sites apart from the Iq site, accounting for the S1QEL 1.1–induced increase in ROS production in Fig. 3C, E.

Figure 7.

Schematic depicting plausible effects of S1QEL 1.1 to increase complex II (succinate)-driven respiration and to decrease complex I (glutamate + malate)-driven respiration. A) During succinate-energized respiration, S1QEL 1.1 is posited to interact with the IQ site of complex I, favoring e− flow toward the IF site and decreasing ROS production. This would favor NADH formation and limit OAA formation when electrons from complex II enter by RET. This will increase forward electron flow at complex II and mitochondrial respiration. B) When electrons enter complex I through NADH in the forward direction, S1QEL 1.1 is posited to have opposite effects by blocking forward flow directed at UQ reduction to UQH, thereby limiting complex I electron flux and mitochondrial respiration. *Although S1QEL 1.1 decreases ROS during succinate-energized respiration and increases ROS on glutamate plus malate, the actual mounts of ROS are still much less on forward electron transport (with or without S1QEL 1.1). MDH, malate dehydrogenase; UQ, ubiquinone; UQH, ubiquinol.

Because S1QEL 1.1 acts in complex I, we reasoned that the compound might also affect respiration by glutamate plus malate–energized mitochondria; that is, on substrates that generate forward electron transport and do not induce RET. Although again speculative, we reasoned that if S1QEL 1.1 favored backflow of electrons during respiration on complex II substrates, we might expect limitation of flow in the forward direction on complex I substrates (Fig. 7B). This is compatible with our finding that S1QEL 1.1 reduced respiration in heart mitochondria respiring on glutamate and malate (Fig. 5A). This is also compatible with our observation that S1QEL 1.1 increased ROS production in these glutamate plus malate–energized mitochondria (Fig. 5C). A plausible explanation for this is that limitation of forward flow through the IQ site might prolong the lifetime of the semiquinone or otherwise increase the possibility of electron delivery to molecular oxygen.

Our findings regarding the effects of S1QEL 1.1 on respiration may seem at odds with findings suggesting that such compounds do not affect oxidative phosphorylation. Brand et al. (17) reported that respiration by succinate-energized muscle mitochondria was not affected by S1QEL 1.1, in spite of reduction in ROS production. These experiments were done at high ΔΨ and in the presence of rotenone, which maintains NADH in the reduced state (3, 4) and prevents OAA formation. In contrast, the effects we found on succinate-energized respiration were observed in the absence of rotenone and were only to prevent the downturn in respiration (Fig. 3) at high [ADP] (low ΔΨ). S1QEL 1.1 did not affect the initial rise in respiration (Fig. 3) when ΔΨ was high, which agrees with the data of Brand et al. (17). We also observed an S1QEL 1.1–mediated reduction in respiration energized by glutamate and malate, an effect that was not evident in the work by Brand et al. (17). Our respiratory studies differed in that we measured O2 flux in mitochondria suspended within an oxygraph respirometer as opposed to mitochondria centrifuged to well bottoms in a Seahorse instrument. Furthermore, we used an ionic respiratory buffer as opposed to a mannitol-sucrose buffer. Moreover, in a recent study using photoaffinity labeling, the researchers reported that S1QEL 1.1 and related compounds bound to a segment of the ND1 subunit of complex 1 in a manner that, potentially, could inhibit forward electron transport (18).

Although our findings have limitations, there are also potentially important physiologic implications. A limitation is that our results obviously pertain to isolated mitochondria. However, considering the inhibitory effect of OAA on SDH, the low amounts needed for inhibition, and the relation to ΔΨ (whether due to ADP or UCP1), it is difficult not to suspect consequences at the cellular, tissue, and even whole-body level. While future effort will be needed to sort this out, our current work does provide impetus in this direction. Such work would likely have implications toward clinical energetics given that brown fat has been identified in humans and might mitigate obesity (29–32) and that skeletal muscle is of obvious importance toward energy utilization. Another limitation is that our studies were not intended to detail the mechanism of action of S1QEL 1.1 and do not go beyond the speculative events shown in Fig. 7. However, our results might be taken to at least suggest that manipulating electron flow through complex I by compounds related to S1QEL 1.1 could eventually have therapeutic impact.

In summary, we show that O2 flux in succinate-energized IBAT mitochondria is regulated in a fashion similar to complex II–energized heart and muscle mitochondria when potential is reduced by high concentrations of ADP. This regulation in IBAT mitochondria is dependent on the action of UCP1 to lower ΔΨ. Our results are consistent with evidence that S1QEL 1.1 reduces ROS at the IQ site of complex I at high ΔΨ during RET in mitochondria energized by succinate. However, at low ΔΨ, S1QEL 1.1 appears to perturb electron transit and impair OAA formation, leading to increased succinate (complex II)-energized respiration. Overall, our findings enhance our knowledge of the dynamic interactions between ΔΨ, OAA accumulation, and inhibition of complex II–energized respiration.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Merit Review Award 2 I01 BX000285-05 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service, and by the Iowa Fraternal Order of the Eagles. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ΔΨ

membrane potential

- 2DOG

2-deoxyglucose

- GDP

guanosine 5′-diphosphate

- IBAT

interscapular brown adipose tissue

- IF

flavin site of complex I

- OAA

oxaloacetate

- RET

reverse electron transport

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- S1QEL 1.1

N1-(3-acetamidophenyl)-N2-(2-(4-methyl-2-(p-tolyl)thiazol-5-yl)ethyl)oxalamide

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

- UCP1

uncoupling protein 1

- UK5099

2-cyano-3-(1-phenylindol-3-yl)prop-2-enoic acid

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L. Yu and W. I. Sivitz designed the research; B. D. Fink, L. Yu, and W. I. Sivitz analyzed data; B. D. Fink and L. Yu performed research; L. Yu contributed analytic tools; and B. D. Fink, L. Yu, and W. I. Sivitz wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bai F., Fink B. D., Yu L., Sivitz W. I. (2016) Voltage-dependent regulation of complex II energized mitochondrial oxygen flux. PLoS One 11, e0154982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink B. D., Bai F., Yu L., Sheldon R. D., Sharma A., Taylor E. B., Sivitz W. I. (2018) Oxaloacetic acid mediates ADP-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial complex II-driven respiration. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 19932–19941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert A. J., Brand M. D. (2004) Inhibitors of the quinone-binding site allow rapid superoxide production from mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39414–39420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scialò F., Sriram A., Fernández-Ayala D., Gubina N., Lõhmus M., Nelson G., Logan A., Cooper H. M., Navas P., Enríquez J. A., Murphy M. P., Sanz A. (2016) Mitochondrial ROS produced via reverse electron transport extend animal lifespan. Cell Metab. 23, 725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand M. D., Nicholls D. G. (2011) Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem. J. 435, 297–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Malley Y., Fink B. D., Ross N. C., Prisinzano T. E., Sivitz W. I. (2006) Reactive oxygen and targeted antioxidant administration in endothelial cell mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39766–39775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azzone G. F., Ernster L., Klingenberg M. (1960) Energetic aspects of the mitochondrial oxidation of succinate. Nature 188, 552–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance B., Hagihara B. (1962) Activation and inhibition of succinate oxidation following adenosine diphosphate supplements to pigeon heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 237, 3540–3545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chance B., Hollunger G. (1960) Energy-linked reduction of mitochondrial pyridine nucleotide. Nature 185, 666–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panov A. V., Kubalik N., Zinchenko N., Ridings D. M., Radoff D. A., Hemendinger R., Brooks B. R., Bonkovsky H. L. (2011) Metabolic and functional differences between brain and spinal cord mitochondria underlie different predisposition to pathology. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 300, R844–R854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panov A. V., Vavilin V. A., Lyakhovich V. V., Brooks B. R., Bonkovsky H. L. (2010) Effect of bovine serum albumin on mitochondrial respiration in the brain and liver of mice and rats. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 149, 187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schollmeyer P., Klingenberg M. (1961) Oxaloacetate and adenosinetriphosphate levels during inhibition and activation of succinate oxidation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 4, 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wojtczak A. B., Wojtczak L. (1964) The effect of oxalacetate on the oxidation of succinate in liver mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 89, 560–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Kadhi O., Melchini A., Mithen R., Saha S. (2017) Development of a LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous detection of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates in a range of biological matrices. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2017, 5391832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmermann M., Sauer U., Zamboni N. (2014) Quantification and mass isotopomer profiling of α-keto acids in central carbon metabolism. Anal. Chem. 86, 3232–3237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong H. S., Dighe P. A., Mezera V., Monternier P. A., Brand M. D. (2017) Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from specific mitochondrial sites under different bioenergetic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 16804–16809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brand M. D., Goncalves R. L., Orr A. L., Vargas L., Gerencser A. A., Borch Jensen M., Wang Y. T., Melov S., Turk C. N., Matzen J. T., Dardov V. J., Petrassi H. M., Meeusen S. L., Perevoshchikova I. V., Jasper H., Brookes P. S., Ainscow E. K. (2016) Suppressors of superoxide-H2O2 production at site IQ of mitochondrial complex I protect against stem cell hyperplasia and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Metab. 24, 582–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banba A., Tsuji A., Kimura H., Murai M., Miyoshi H. (2019) Defining the mechanism of action of S1QELs, specific suppressors of superoxide production in the quinone-reaction site in mitochondrial complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 6550–6561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu L., Fink B. D., Sivitz W. I. (2015) Simultaneous quantification of mitochondrial ATP and ROS production. Methods Mol. Biol. 1264, 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wojtczak L., Zaluska H., Wroniszewska A., Wojtczak A. B. (1972) Assay for the intactness of the outer membrane in isolated mitochondria. Acta Biochim. Pol. 19, 227–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu L., Fink B. D., Herlein J. A., Sivitz W. I. (2013) Mitochondrial function in diabetes: novel methodology and new insight. Diabetes 62, 1833–1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu L., Fink B. D., Herlein J. A., Oltman C. L., Lamping K. G., Sivitz W. I. (2014) Dietary fat, fatty acid saturation and mitochondrial bioenergetics. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 46, 33–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. (1994) NMR View: a computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee S. G., Chang T. S., Jeong W., Kang D. (2010) Methods for detection and measurement of hydrogen peroxide inside and outside of cells. Mol. Cells 29, 539–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hildyard J. C., Ammälä C., Dukes I. D., Thomson S. A., Halestrap A. P. (2005) Identification and characterisation of a new class of highly specific and potent inhibitors of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1707, 221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong H. S., Benoit B., Brand M. D. (2019) Mitochondrial and cytosolic sources of hydrogen peroxide in resting C2C12 myoblasts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 130, 140–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinlan C. L., Orr A. L., Perevoshchikova I. V., Treberg J. R., Ackrell B. A., Brand M. D. (2012) Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27255–27264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cypess A. M., Lehman S., Williams G., Tal I., Rodman D., Goldfine A. B., Kuo F. C., Palmer E. L., Tseng Y. H., Doria A., Kolodny G. M., Kahn C. R. (2009) Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1509–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito M., Okamatsu-Ogura Y., Matsushita M., Watanabe K., Yoneshiro T., Nio-Kobayashi J., Iwanaga T., Miyagawa M., Kameya T., Nakada K., Kawai Y., Tsujisaki M. (2009) High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes 58, 1526–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Marken Lichtenbelt W. D., Vanhommerig J. W., Smulders N. M., Drossaerts J. M., Kemerink G. J., Bouvy N. D., Schrauwen P., Teule G. J. (2009) Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1500–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virtanen K. A., Lidell M. E., Orava J., Heglind M., Westergren R., Niemi T., Taittonen M., Laine J., Savisto N. J., Enerbäck S., Nuutila P. (2009) Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1518–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.