This cross-sectional study examines 8 clinical practice guidelines for consistency in recommendations for diagnosis and management of hypertension.

Key Points

Question

How consistent are recommendations from clinical practice guidelines regarding the diagnosis and management of hypertension?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 8 clinical practice guidelines found notable inconsistency in recommendations. The inconsistency could not be explained by any single source, importance of recommendations, or by areas of insufficient evidence.

Meaning

These findings suggest that individual clinical practice guidelines are poor proxies for a universally accepted source of truth; instead, classifying the consistency of recommendations across guidelines may help better categorize recommendations for clinical practice, and shared decision-making support is preferred over recommendations for preference-sensitive decisions.

Abstract

Importance

Hypertension is very common, but guideline recommendations for hypertension have been controversial, are of increasing interest, and have profound implications.

Objective

To systematically assess the consistency of recommendations regarding hypertension management across clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study of hypertension management recommendations included CPGs that had been published as of April 2018. Two point-of-care resources that provided graded recommendations were included for secondary analyses. Discrete and unambiguous specifications of the population, intervention, and comparison states were used to define a series of reference recommendations. Three raters reached consensus on coding the direction and strength of each recommendation made by each CPG. Three independent raters reached consensus on the importance of each reference recommendation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were rates of consistency for direction and strength among CPGs. Sensitivity analyses testing the robustness were conducted by excluding recommendation statements that were described as insufficient evidence, excluding single recommendation sources, and stratifying by importance of recommendations.

Results

The analysis included 8 CPGs with a total of 71 reference recommendations, 68 of which had clear recommendations from 2 or more CPGs. Across CPGs, 22 recommendations (32%) were consistent in direction and strength, 18 recommendations (27%) were consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength, and 28 recommendations (41%) were inconsistent in direction. The rate of consistency was lower in secondary analyses. When insufficient evidence ratings were excluded, there was still substantial inconsistency, and a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis suggested the inconsistency could not be attributed to any single recommendation source. Inconsistency in direction was more common for recommendations deemed to be of lower importance (11 of 20 recommendations [55%]), but 17 of 48 high-importance recommendations (35%) had inconsistency in direction.

Conclusions and Relevance

Hypertension is a common chronic condition with widespread expectations surrounding guideline-based care, yet CPGs have a high rate of inconsistency. Further investigations should determine the reasons for inconsistency, the implications for recommendation development, and the role of synthesis across recommendations for optimal guidance of clinical care.

Introduction

The recommendation from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and accompanying organizations1 to lower the blood pressure threshold for the diagnosis of hypertension in their clinical practice guideline (CPG) has been controversial, especially because adhering to such guidance would result in classifying nearly half the US population as unwell and subjecting them to treatment.2 Moreover, the diagnostic classifications and blood pressure thresholds deemed to be normal vary across CPGs.1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

When independent groups have reviewed the same evidence, considered various key factors, such as values and preferences, and come to the same conclusions regarding a recommendation, the credibility of the recommendation is increased. This is comparable to research results in which the replication of findings by repeated experiments increases their credibility. However, when groups reach inconsistent conclusions about a recommendation, the inconsistency can create confusion. If combined with lack of clarity, inaccuracy, or poor alignment with the context of clinical practice, inconsistent recommendations have the potential for undesirable consequences, such as wasting resources and contributing to worse clinical outcomes.

Hypertension is the most common specific primary diagnosis for ambulatory care visits among adults in the United States,10 and more than 65 currently active CPGs are available worldwide for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension.11,12 We sought to determine the consistency of recommendations for evaluation and management of hypertension across prominent CPGs. In the absence of an existing method for such an evaluation, we developed a method to complete our study.

Research about CPGs is often conducted by CPG developers and methodologists, and interpretation may lack public and patient perspectives. We initially sought to involve patient and public representatives in our study, and their interests led to additional assessments of the CPGs for evidence of public and patient involvement, patient-facing information, and shared decision-making tools.

Methods

This study is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study did not involve any human subject testing or use of patient data and is thus exempt from institutional review board approval.

Search and Selection

In current clinical practice, many clinicians use electronic point-of-care (POC) resources to find CPGs or instead of directly reading CPGs. Two POC resources, DynaMed Plus (DMP)13 and UpToDate (UTD),14 provide lists of CPGs and explicit recommendations based on CPGs. In April 2018, we searched the full lists of CPGs from 5 sources: DMP,13 UTD,14 Guidelines International Network, National Guideline Clearinghouse, and Turning Research into Practice. Nine of us (B.S.A., A.P., E.J.v.Z., Z.F., A.F.S., P.O., G.E., A.Q., and I.K.) developed inclusion criteria by consensus to select the CPGs most likely to be informing current practice and be practical for analysis. We selected CPGs that were currently active, publicly available, produced or updated in or after 2010, published in and intended for a target audience with an official language of English, considered to be used as the primary source of guidance for clinical care by a large population of health care practitioners, and relevant to the general management of hypertension (eg, addressing blood pressure treatment thresholds or medication selections in patients with or without comorbidities and not limited solely to patients with specific comorbidities).

Recommendation Specification

We identified the recommendations regarding evaluation and management of hypertension in the selected CPGs, DMP,13 and UTD.14 Differences in population, intervention, and comparator concepts precluded direct analysis of consistency in simple forms, so we needed to create a reference standard to compare recommendations against. We generated reference recommendations using population-intervention-comparison (PIC) combinations to provide a consistent framework to disambiguate the frames of reference for expressing recommendations. We combined or separated reference recommendations (ie, PIC specifications) iteratively during consistency mapping and agreed by consensus of all coders (B.S.A., A.P., E.J.v.Z., Z.F., A.F.S., and M. Mayer) to derive the final reference recommendations.

Coding Direction and Strength of Recommendations

To minimize bias, for each reference recommendation a recommendation coder (A.P., E.J.v.Z., Z.F., or M. Mayer) independently coded the direction and strength of recommendation from each recommendation source. A recommendation code reviewer (A.P., E.J.v.Z., Z.F., A.F.S., or M. Mayer) independently checked the coding of the recommendation coder. Three investigators with clinical experience in hypertension management (A.F.S., B.S.A., and M. Mayer) reviewed the ratings from both the recommendation coder and reviewer, and we considered final codes confirmed when we had full consensus. Individuals who served in more than 1 role throughout this process (A.P., E.J.v.Z., Z.F., A.F.S., and M. Mayer) only served in 1 role for any given reference recommendation and recommendation source pair.

For each recommendation and CPG pair, the coding team assessed 3 factors. First, we assessed whether the CPG addressed the recommendation to an extent that allowed consistency mapping. If it did not, we considered the recommendation out of scope for that source and applied no further coding.

Second, the direction of recommendation was assessed as for if the source recommended the intervention over the comparison, against if the source recommended the comparison over the intervention, insufficient if the source did not recommend for or against the intervention but the PIC specification was within the scope to be addressed, or different if the source assertion could not be clearly classified as for, against, or insufficient. In the absence of a statement of insufficient evidence to recommend for or against, we coded a discussion of the relevant evidence as insufficient rather than out of scope. Ratings of different became candidates for realignment of PIC specifications as described previously.

Third, we assessed the strength of recommendation. A strong rating was coded if the source rated the recommendation as strong, rated the recommendation at the highest degree of certainty, or used definitive language implying the highest degree of obligation or expectations for following the recommendation. A weak rating was used if the source rated the recommendation at less than the highest degree of certainty or used nondefinitive language implying a lower degree of obligation or expectation for following the recommendation. A different rating was used if the recommendation could not be clearly classified as strong or weak but the intention was clear, such as strong for one subpopulation and weak for another subpopulation. Ratings of different triggered consideration of clarification of the PIC specifications and recoding across the reference recommendation. Additionally, a recommendation was rated as unclear if it was not clear enough to imply whether the assertion was strong or weak, but the direction was clear; or none for recommendations for which the direction was neither for nor against.

After we coded all reference recommendations across the CPGs, we assessed the rate of consistency for direction and strength. We did not include recommendations coded as out of scope or different in any of the analyses for consistency. We only applied consistency assessments if 2 or more CPGs provided a direction rating of for, against, or insufficient.

For assessments of consistency in direction, if all recommendations were for, all recommendations were against, or all recommendations were insufficient, we considered the reference recommendation consistent in direction. If any recommendation was for and any other recommendation was against, then we considered the reference recommendation inconsistent in direction. If 1 or more recommendations were for or against and 1 or more recommendations were insufficient, then we considered the reference recommendation consistent in direction if 80% or more of the recommendations agreed; otherwise we considered the reference recommendation inconsistent in direction. We added this criterion to modify the definition of consistency in direction in response to prepublication peer review.

For assessments of consistency in strength, we did not rate consistency in strength if the reference recommendation was inconsistent in direction. If all recommendations were strong or all recommendations were weak, then we considered the reference recommendation consistent in strength. If any recommendation was strong and any other recommendation was weak, we considered the reference recommendation inconsistent in strength. For any reference recommendations we considered consistent in direction but had any ratings of insufficient, we considered these weak for assessment of consistency of strength of recommendations.

Updates After April 2018 Search

Hypertension Canada8 published an updated guideline online in March 2018 and in print in May 2018. Compared with the previous version of the guideline, the 2018 guideline was the same for all reference recommendations, so we report Hypertension Canada’s guideline as the 2018 guideline.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Society of Hypertension (ESH) published updated guidelines online ahead of print on August 25, 2018.9 All main and sensitivity analyses used the ESH and ESC guidelines from 20137 according to our specified protocol and date limitations. However, 4 of us (B.S.A., A.P., Z.F., and M. Mayer) applied single coding for the 71 reference recommendations using the 2018 CPG from the ESC and ESH9 to determine if it would have appreciable effects on the overall analysis.

Patient and Public Involvement

Four patient and public research partners (U.G., D.D.C., M. Mittelman, and C.B.-N.), along with 2 academic authors (A.P. and E.J.v.Z.), coded the 8 CPGs and 2 POC resources for evidence of patient and public involvement, patient-facing information, and shared decision-making tools. Next, they appraised and commented on the draft paper without the discussion or conclusion so their included recommendations could be informed by a fresh perspective.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis that excluded insufficient ratings from the analysis. We also conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis assessing rates of consistency with each CPG excluded one at a time. Finally, we repeated the analyses using the same methods but treating DMP13 and UTD14 functionally as additional CPGs. We conducted an additional sensitivity analysis that stratified the reference recommendations by importance. For each PIC specification, the chair and 2 members of the Finnish National Guideline Panel on Hypertension rated the importance of giving a recommendation. It was considered important to give a recommendation if the recommendation was needed for patient care to benefit patients. If it was unlikely that a recommendation about the PIC would benefit patients, then it was not considered important to give a recommendation. The raters were instructed not to consider the direction of the recommendation or their agreement with the recommendation when they completed their ratings. The raters did not know which guidelines were included in the study, and they were blinded to the results of the rating for consistency in direction and strength. The raters originally rated the importance as high, moderate, or low independently, and then discussed to reach consensus on recommendations for cases for which their independent ratings disagreed. In the final reporting, the moderate and low importance groups were combined to create a lower importance group. Analyses were conducted using Excel spreadsheet software (Microsoft Corp).

Results

Selection and Data Extraction

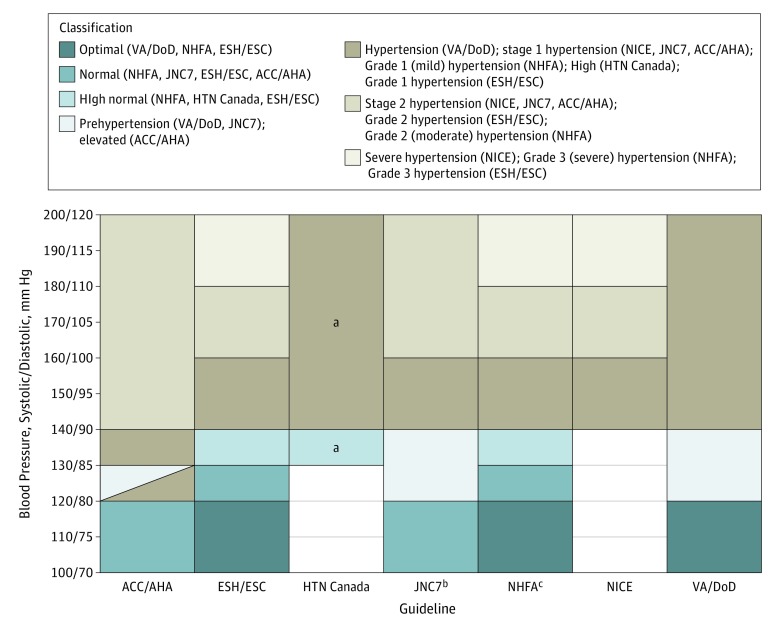

The initial search yielded 75 CPGs. We excluded 67 of these based on our selection criteria (eTable 1 in the Supplement), with the remaining 8 CPGs (Table 1) coming from the United States,1,5,15,16 Australia,6 Canada,8 Europe,7 and the United Kingdom.4 From these 8 CPGs and 2 POC resources (DMP13 and UTD14), we generated 71 reference recommendations with discrete and unambiguous specifications of the population, intervention, and comparison (Table 2) (eTable 2 in the Supplement) and completed ratings as described (eTable 3 in the Supplement). We also reported classifications stratified by blood pressure thresholds (Figure).

Table 1. Recommendation Sources Meeting Inclusion Criteriaa.

| Full Title | Represented Entity |

|---|---|

| Hypertension in Adults: Diagnosis and Management4 | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)7 | European Society of Hypertension and European Society of Cardiology |

| 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)15 | Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee |

| VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in the Primary Care Setting5 | Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense |

| Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in Adults6 | National Heart Foundation of Australia and National Heart Foundation of Australia - National Blood Pressure and Vascular Disease Advisory Committee |

| 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines1 | American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Academy of Physician Assistants, Association of Black Cardiologists, American College of Preventive Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American Pharmacists Association, American Society of Hypertension, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, National Medical Association, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association |

| Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher vs Lower Blood Pressure Targets: a Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians16 | American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians |

| Hypertension Canada’s 2018 Guidelines for Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children8b | Hypertension Canada |

Recommendation sources are listed in ascending order of date of publication or update.

These guidelines were published in print in May of 2018, after the initial search described in the Methods section; however, the online version was published in March of 2018. Therefore, we included the 2018 version in the analysis instead of the previous release.

Table 2. Reference Recommendations Considered.

| Recommendation No. | Short Description of Reference Recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1 | In all patients, BP should be measured with appropriate cuff size, with the patient calm, seated, and with arm supported at heart level vs measuring BP without specific measurement parameters |

| 2 | In all patients with suspected hypertension, diagnosis using office BP should be based on ≥2 measurements per office visit at ≥2 office visits vs a single measurement |

| 3 | In all adults with suspected hypertension, diagnosis based on nonautomated office BP should be SBP >140 mm Hg or DBP >90 mm Hg vs a different cutoff |

| 4 | In adults with suspected hypertension and without diagnostic uncertainty or BP variability, use ABPM for diagnostic confirmation vs diagnosing based on clinic BP alone |

| 5 | In adults with suspected hypertension and without diagnostic uncertainty or BP variability, use HBPM for diagnostic confirmation vs diagnosing based on clinic BP alone |

| 6 | In adults with suspected hypertension and without diagnostic uncertainty or BP variability, use ABPM vs HBPM for diagnostic confirmation |

| 7 | In adults with suspected hypertension with diagnostic uncertainty, use ABPM vs not using ABPM |

| 8 | In adults with suspected blood pressure variability, use ABPM vs not using ABPM |

| 9 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a baseline routine blood chemistry analysis vs not performing it |

| 10 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a fasting blood glucose test vs not performing a fasting blood glucose test |

| 11 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, obtain a fasting lipid profile vs no lipid testing |

| 12 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a urine dipstick analysis for blood a protein vs no urine testing |

| 13 | In adults with newly diagnosed with hypertension, perform an ECG vs not performing an ECG |

| 14 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a hemoglobin or hematocrit analysis vs not performing a hemoglobin or hematocrit analysis |

| 15 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a serum calcium analysis vs no calcium testing |

| 16 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a serum uric acid analysis vs no uric acid testing |

| 17 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform urine testing for albumin to creatinine ratio vs no testing for quantified urine albumin |

| 18 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform a 24-hour urine analysis for albumin content vs no testing for quantified urine albumin |

| 19 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, perform urine testing for albumin to creatinine ratio vs a 24-hour urine test for albumin content |

| 20 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension, conduct targeted screening for suspected causes of secondary hypertension vs not conducting any such testing |

| 21 | In adults with newly diagnosed hypertension with suspected structural heart disease, perform an ECG vs not performing an ECG |

| 22 | In adults with hypertension and overweight or obesity, counsel regarding weight loss vs not providing such counseling |

| 23 | In adults with hypertension, counsel regarding dietary changes (general concept), including fat restriction or increasing fruit and vegetable intake, vs not providing any such counseling |

| 24 | In adults with hypertension, counsel regarding physical activity (which may include aerobic exercise) vs not providing any such counseling |

| 25 | In adults who smoke and have hypertension, counsel patients to quit smoking vs not providing any such counseling |

| 26 | In adults with hypertension, counsel regarding salt restriction or reducing sodium intake vs not providing any such counseling |

| 27 | In adults with hypertension and heavy alcohol use, counsel to moderate alcohol consumption vs not providing any such counseling |

| 28 | In adults aged 18-60 y with hypertension, no diabetes, no coronary artery disease, and no chronic kidney disease, target a BP of ≤140/90 mm Hg vs another BP |

| 29 | In adults aged 60-80 y with hypertension, no diabetes, no coronary artery disease, and no chronic kidney disease, target a BP of ≤140/90 mm Hg vs another BP |

| 30 | In adults aged >50 y with increased cardiovascular risk, target an SBP of <120 mm Hg vs another SBP |

| 31 | In adults aged >75-80 y with hypertension, target a BP of ≤150/90 mm Hg vs a lower BP target |

| 32 | In adults with hypertension and diabetes, target a BP of <140/90 mm Hg vs another BP |

| 33 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease without proteinuria and without diabetes, target a BP of <140/90 mm Hg vs another BP |

| 34 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease with proteinuria, target a BP of <130/80 mm Hg vs another BP |

| 35 | In adults with hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes, target a BP of <130/80 mm Hg vs another BP |

| 36 | In adults aged <55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider a thiazide-type diuretic as a therapeutic option vs not considering a thiazide-type diuretic as a therapeutic option |

| 37 | In adults aged >55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider a thiazide-type diuretic as a therapeutic option vs not considering a thiazide-type diuretic as a therapeutic option |

| 38 | In adults with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, use a thiazide-type diuretic as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over a thiazide-type diuretic |

| 39 | In adults aged <55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider an ACE-I as a therapeutic option vs not considering an ACE-I as a therapeutic option |

| 40 | In adults aged >55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider an ACE-I as a therapeutic option vs not considering an ACE-I as a therapeutic option |

| 41 | In adults with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over an ACE-I |

| 42 | In adults aged <55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider an ARB as a therapeutic option vs not considering an ARB as a therapeutic option |

| 43 | In adults aged >55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider an ARB as a therapeutic option vs not considering an ARB as a therapeutic option |

| 44 | In adults with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, use an ARB as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over an ARB |

| 45 | In adults aged <55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider a CCB as a therapeutic option vs not considering a CCB as a therapeutic option |

| 46 | In adults aged >55 y with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider a CCB as a therapeutic option vs not considering a CCB as a therapeutic option |

| 47 | In adults with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, use a CCB as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over a CCB |

| 48 | In adults with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, consider a β-blocker as a therapeutic option vs not considering a β-blocker as a therapeutic option |

| 49 | In adults with hypertension and no comorbidity requiring specific initial pharmacotherapy, use a β-blocker as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over a β-blocker |

| 50 | In adults with hypertension and diabetes, consider an ACE-I or ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ACE-I or ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 51 | In adults with hypertension and diabetes, use an ACE-I or ARB as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over an ACE-I or ARB |

| 52 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease, consider an ACE-I as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ACE-I as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 53 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs an ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 54 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease without microalbuminuria, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs a medication other than an ACE-I or ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 55 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease with microalbuminuria, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs a medication other than an ACE-I or ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 56 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease who are intolerant to ACE-I, consider an ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 57 | In adults with hypertension and chronic kidney disease who are intolerant to ACE-I, use an ARB as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over an ARB |

| 58 | In adults with hypertension and coronary artery disease (ie, ischemic heart disease) and no prior myocardial infarction, consider an ACE-I as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ACE-I as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 59 | In adults with hypertension and prior myocardial infarction, consider an ACE-I as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ACE-I as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 60 | In adults with hypertension and coronary artery disease (ie, ischemic heart disease) but no prior myocardial infarction, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs an ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 61 | In adults with hypertension and prior myocardial infarction, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs an ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 62 | In adults with hypertension and coronary artery disease (ie, ischemic heart disease) but no prior myocardial infarction, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs a medication other than an ACE-I or ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 63 | In adults with hypertension and prior myocardial infarction, use an ACE-I as the preferred therapeutic option vs a medication other than an ACE-I or ARB being considered equally or more preferred |

| 64 | In adults with hypertension and coronary artery disease (ie, ischemic heart disease) but no prior myocardial infarction who are intolerant to ACE-I, consider an ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 65 | In adults with hypertension and prior myocardial infarction who are intolerant to ACE-I, consider an ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy vs not considering an ARB as a therapeutic option for first-line therapy |

| 66 | In adults with hypertension and coronary artery disease (ie, ischemic heart disease) but no prior myocardial infarction who are intolerant to ACE-I, use an ARB as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over an ARB |

| 67 | In adults with hypertension and prior myocardial infarction who are intolerant to ACE-I, use an ARB as the preferred therapeutic option vs another medication being used in preference over an ARB |

| 68 | In adults with hypertension and recent myocardial infarction, use a β-blocker vs not using a β-blocker |

| 69 | In adults with hypertension and heart failure, use an ACE-I vs not using an ACE-I |

| 70 | In adults with hypertension and heart failure, use a β-blocker vs not using a β-blocker |

| 71 | In adults with hypertension and heart failure who are intolerant to ACE-I, use an ARB vs not using an ARB |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; ACE-I, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; HBPM, home blood pressure monitoring; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure. Classifications by Blood Pressure Thresholds in Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Thresholds displayed are based on blood pressure measured in a clinic setting. Many guidelines emphasize the importance of out-of-clinic measurements (ie, home or ambulatory measurements) to establish diagnosis of hypertension. American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians guidelines are not shown because they did not address diagnostic thresholds. ACC/AHA indicates American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Academy of Physician Assistants, Association of Black Cardiologists, American College of Preventive Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American Pharmacists Association, American Society of Hypertension, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, National Medical Association, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; ESH/ESC, European Society of Hypertension and European Society of Cardiology; HTN Canada, Hypertension Canada; JNC7, Panel Members Appointed to the Seventh Joint National Committee; NHFA, National Heart Foundation of Australia and National Heart Foundation of Australia–National Blood Pressure and Vascular Disease Advisory Committee; NICE indicates National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; and VA/DoD, Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense.

aIf measured using a nonautomated office blood pressure device; if using an automated office blood pressure device, systolic blood pressure greater than 135 mm Hg is considered high.

bThe panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee focused on management, not reaffirming or redefining thresholds; therefore, thresholds from JNC7 were used.

cNot shown is isolated systolic hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg.

Primary Analysis

Three reference recommendations were addressed clearly by only 1 CPG, so 68 reference recommendations were evaluated for our primary analysis. Considering all 8 CPGs, we found consistency in both direction and strength for 22 reference recommendations (32%) (Table 3; eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Recommendation sources consistently provided strong recommendations concerning some of the methods of measuring blood pressure (eg, the use of appropriate cuff size, patient position, and arm at heart level), having more than 1 measurement prior to diagnosing hypertension, some lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk reduction, the use of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and β-blockers in patients with heart failure, and the use of β-blockers in patients with recent myocardial infarction.

Table 3. Consistency in Direction and Direction and Strength Across Clinical Practice Guidelines.

| Analysis | Reference Recommendations, No. | Consistency, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Direction and Strength | ||

| Primary analysis | 68 | 40 (58.8) | 22 (32.4) |

| Primary analysis excluding insufficient ratings | 67 | 42 (62.7) | 28 (41.8) |

| Excluding | |||

| American College of Cardiologya | 66 | 43 (65.2) | 24 (36.4) |

| American College of Physiciansb | 68 | 40 (58.8) | 22 (32.4) |

| European Society of Hypertensionc | 65 | 41 (63.1) | 24 (36.9) |

| Hypertension Canada | 65 | 39 (60.0) | 21 (32.3) |

| Eighth Joint National Committee | 68 | 40 (58.8) | 28 (41.2) |

| National Heart Foundation of Australiad | 67 | 40 (59.7) | 22 (32.8) |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | 68 | 44 (64.7) | 22 (32.4) |

| Department of Veterans Affairse | 67 | 40 (59.7) | 28 (41.8) |

| Considering recommendations | |||

| High-importance | 48 | 31 (64.6) | 20 (41.7) |

| Lower-importance | 20 | 9 (45) | 2 (10) |

Full title, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, American Academy of Physician Assistants, Association of Black Cardiologists, American College of Preventive Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American Pharmacists Association, American Society of Hypertension, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, National Medical Association, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association.

Full title, American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Full title, European Society of Hypertension and European Society of Cardiology.

Full title, National Heart Foundation of Australia and National Heart Foundation of Australia–National Blood Pressure and Vascular Disease Advisory Committee.

Full title, Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense.

We found another 18 reference recommendations (26%) to be consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength (Table 3; eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). For example, sources varied in the strength of recommendation regarding the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring for diagnosis of hypertension, inclusion of serum uric acid test results in the initial evaluation of hypertension, and the use of specific medications as options for first-line pharmacotherapy in patients without comorbidities and in patients with specific comorbidities.

We found consistency in direction regardless of strength for 40 reference recommendations (59%) (Table 3; eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). This gives a 41% (28/68) rate of inconsistency in direction. These included such recommendations as specific cutoffs for the diagnosis of hypertension, blood pressure treatment goals, and the use of specific medications as options or preferred options for first-line pharmacotherapy in patients without comorbidities and in patients with specific comorbidities.

Sensitivity Analyses

Rates of inconsistency remained high when we removed insufficient ratings from consideration. Across CPGs, we found 28 reference recommendations (42%) were consistent in direction and strength, 14 reference recommendations (21%) were consistent in direction but not strength, and 25 reference recommendations (37%) were inconsistent in direction (Table 3) (eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

The results of a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis suggested that no single recommendation source could explain the inconsistency (eTables 5-13 in the Supplement). Consistency in direction rates changed by an absolute 0% to 6.4%, and consistency in direction and strength rates changed by an absolute −0.1% to 9.4% (Table 3). If also excluding insufficient ratings, the consistency in direction rates changed by an absolute 3.9% to 14.6%, and consistency in direction and strength rates changed by an absolute 9.4% to 18.3% (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

The ratings from the Finnish guideline panel yielded 48 high-importance reference recommendations and 20 lower-importance reference recommendations. Of the 48 high-importance reference recommendations, 20 (42%) were consistent in direction and strength, 11 (23%) were consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength, and 17 (35%) were inconsistent in direction. Of 20 lower-importance reference recommendations, 2 (10%) were consistent in direction and strength, 7 (35%) were consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength, and 11 (55%) were inconsistent in direction (Table 3) (eTable 14 and eTable 15 in the Supplement).

Secondary Analysis

International variation is not a substantial explanation for inconsistency. The primary analysis limited to the 4 CPGs from the United States (American College of Cardiology et al,1 American College of Pharmacists and American Academy of Family Physicians,16 Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee,15 and US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense5) found 50 recommendations addressed by 2 or more guidelines, with 15 reference recommendations (30%) consistent in direction and strength, 17 reference recommendations (34%) consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength, and 18 reference recommendations (36%) inconsistent in direction.

Repeating the analyses with DMP13 and UTD14 included as recommendation resources provided similar rates of consistency in direction but further reductions in consistency in strength of recommendations across recommendation sources (eTables 16-27 in the Supplement). Across 10 recommendation sources with 71 reference recommendations, we found consistency in both direction and strength for 12 reference recommendations (17%) (eTable 28 in the Supplement). We found 28 reference recommendations (39%) to be consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength. We found consistency in direction regardless of strength for 40 reference recommendations (56%). This means 31 reference recommendations (44%) had inconsistency in direction. With sensitivity analysis removing insufficient ratings from consideration, across all recommendation sources, we found 17 reference recommendations (24%) consistent in direction and strength, 26 reference recommendations (37%) consistent in direction but not strength, and 28 reference recommendations (39%) inconsistent in direction. The results of a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis suggested that no single recommendation source could explain the inconsistency. Consistency in direction rates changed by an absolute −0.6% to 5.7% (or 11.3% if excluding insufficient ratings), and consistency in direction and strength rates changed by an absolute 0% to 11.7% (or 21.3% if excluding insufficient ratings) (eTable 28 in the Supplement).

The results from consideration of the 2018 ESC and ESH updates are shown in eTable 29 in the Supplement. The 2018 updates resulted in 13 changes in coding from the 2013 guidelines, but none changed the consistency ratings for direction or strength in the primary analysis.

Patient and Public Involvement

Of the 10 recommendation sources, 1 source (National Institute for Health Care Excellence4) reported patient or public involvement, either directly in coproducing recommendations or indirectly by providing feedback. Six sources (American College of Cardiology et al,1 American College of Pharmacists and American Academy of Family Physicians,16 DMP,13 Hypertension Canada,8 National Heart Foundation of Australia and National Heart Foundation of Australia,6 and US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense5) included very general information about how to include patients in individual decision-making, and 3 sources (DMP,13 National Institute for Health Care Excellence,4 and UTD14) provided direct-to-patient guidance. Two sources made tools available to help patients participate in individual decision-making: Hypertension Canada suggested an existing tool, and DMP integrated the tool within the POC recommendation.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study found a substantial amount of inconsistency across prominent recommendation sources for hypertension management, and the inconsistency could not be attributed to any particular source. The best possible outcome of inconsistency is adding nuance, but in our experience, this inconsistency more commonly leads to confusion and frustration among clinicians, who already face considerable demands in their day-to-day practice.

Clinical practice guidelines can influence outcomes in medical malpractice claims and can be used by plaintiffs alleging a breach of the standard of care or defendants asserting compliance with the standard of care.17 The inconsistency across CPGs suggests a problem with asserting standards of care based on a CPG, even if the CPG being used seems well referenced with substantial underlying methodology.

To our knowledge, this is the first report providing a systematic approach to assessing the consistency of recommendations across CPGs. Strengths of this approach include a reproducible method for defining reference recommendations, coding consistency, and involvement of multiple raters with clinical and methodological expertise.

Reasons for inconsistency may result from different dates of publication and timing of evidence evaluation, different methods of evidence selection and interpretation, different factors considered when formulating recommendations, different values and preferences, and different types and degrees of stakeholder involvement. Further research is needed to investigate the causes of inconsistency, but that is beyond the scope of our analysis. There may be greater inconsistency in direction for reference recommendations considered to be of lower importance (11 of 20 reference recommendations [55%]) than for those considered highly important (17 of 48 recommendations [35%]). However, we still found substantial inconsistency in areas of high importance.

We propose a simple method to classify consistency in direction and strength of recommendations (Box). Of note, only a minority of the reference recommendations (ie, those consistent in direction and strength) would be considered strong guidance. These recommendations could perhaps be considered a standard of care for hypertension management or could at least be considered strong guidance with a global perspective. Conversely, most recommendations, even those presented as strong recommendations in certain CPGs, should not be considered a true or stable standard of care, as one can easily find opposing standards from reputable sources. For reference recommendations consistent in direction but inconsistent in strength, we propose these be considered weak guidance from a global perspective with general agreement that such actions warrant consideration but no expectation or obligation for use in most patients.

Box. Criteria for Classification of Recommendations.

Strong Guidance

All recommendation sources are consistent in direction and strong in strength:

All recommendation sources provide strong recommendations (or the highest degree of certainty that desirable consequences outweigh undesirable consequences) for the action.

There is a qualified rationale (ie, systematic review, nonconflicted multidisciplinary expertise, and explicit consideration of values and preferences).

There is no discrepant opinion with a qualified rationale.

Weak Guidance

All recommendation sources are consistent in direction but consistently weak in strength or inconsistent in strength:

All recommendation sources provide recommendations for the action.

Not all recommendation sources provide a strong recommendation.

Inconsistent Guidance

≥1 Of the following is present:

≥1 Recommendation source recommends for and ≥1 recommendation source recommends against the action; or

≥1 Recommendation source recommends for the action and ≥1 recommendation source declares insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the action.

We found inconsistent guidance for a disconcertingly high proportion of reference recommendations. This suggests that clinicians evaluating and treating hypertension are often faced with impossible expectations, in that following one guideline’s recommendations would mean going against recommendations from another guideline.

Regardless of measures taken to improve CPG development, a high degree of consistency and strong guidance may be unrealistic in hypertension management. The direct evidence for precise actions is often limited, the thresholds for action are often more continuous than binary, and the relative importance of benefits and harms is sensitive to an individual patient’s values and preferences.

Patient and Public Perspectives

Our patient and public research partners also read and coded the guidelines, so they were able to see inconsistencies for themselves. They were concerned that an ideal trial population might respond very differently to an intervention than real people with comorbidities and that the recommendation sources had minimal guidance concerning adverse effects. They agreed this is an area in which clinicians and patients might need guidance the most for realistic shared decision-making.

Our patient and public research partners also had multiple recommendations, such as an international protocol for hypertension with room for clinician variance but with strict reporting for guideline variance or inconsistencies, including conflicts of interest (eg, who might benefit financially if a population that would have been considered within normal ranges the previous year population would now be recommended a given intervention because they are no longer considered within normal ranges). They recommended the guidelines link to patient-facing information and detail how the guidelines were informed by end users. To individualize the information, the benefits, risks, alternatives, and what happens if I do nothing (also known as the BRAN approach) information approach might be used, as this could form a foundation for patients needing to make decisions about an intervention. This could be accompanied by a calculator for individual risk when available, which patients could use to evaluate the tradeoffs with their values and preferences. The development of a decision tree or visual infographic using if no or yes, then what arguments could be a useful visual aid. The decision aid would provide or link to information on adverse reactions, including effects on comorbidities and the duration of adverse effects. An online decision aid could be used before an appointment, so patients could process new medical information and be better prepared for the clinical appointment.

Consideration of a patient’s values and preferences is a fundamental part of practicing evidence-based medicine.18 Therefore, public and patient involvement is encouraged in CPG development,19,20 just as shared decision-making is encouraged in clinical practice.21,22,23,24 With a substantial proportion of hypertension management guidance being weak or inconsistent, shared decision-making could replace algorithmic instructions as a primary framework for an approach to health care, but this will require development of patient decision aids and workflow support tools to make it practical.22

Limitations

This study had some limitations, including that, to our knowledge, there was no previously established method for objectively evaluating and reporting the consistency of recommendations. This is the first analysis using this method, so it may not be predictive of the rate of consistency across recommendation sources for conditions other than hypertension. Additionally, we transformed all recommendations to a dichotomous strength rating, so some inconsistency may result as an artifact of converting recommendations with 3 or more strength classifications to a dichotomous system. However, we do not believe this is a substantial or spurious contributor to the inconsistency found across recommendations.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study found that current CPGs have substantial inconsistency in recommendations for management of hypertension. No single CPG reflects a universal standard for care.

eTable 1. Excluded Clinical Practice Guidelines

eTable 2. Population-Intervention-Comparator Specifications of Reference Recommendations

eTable 3. Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines

eTable 4. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines

eTable 5. Consistency of Direction and Direction and Strength Across Clinical Practice Guidelines With Sensitivity Analysis for Excluding Insufficient Ratings

eTable 6. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding American College of Cardiology

eTable 7. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding American College of Physicians

eTable 8. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding European Society of Hypertension

eTable 9. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding Hypertension Canada

eTable 10. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding Eighth Joint National Committee

eTable 11. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding National Heart Foundation of Australia

eTable 12. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

eTable 13. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding Department of Veterans Affairs

eTable 14. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Among High Importance Recommendations

eTable 15. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Among Lower Importance Recommendations

eTable 16. Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources

eTable 17. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources

eTable 18. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding American College of Cardiology

eTable 19. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding American College of Physicians

eTable 20. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding DynaMed Plus

eTable 21. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding European Society of Hypertension

eTable 22. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding Hypertension Canada

eTable 23. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding Eighth Joint National Committee

eTable 24. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding National Heart Foundation of Australia

eTable 25. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

eTable 26. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding UpToDate

eTable 27. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding Department of Veterans Affairs

eTable 28. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings Across All Recommendation Sources, With Sensitivity Analysis for Excluding Insufficient Ratings

eTable 29. Changes from the 2013 to the 2018 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension

References

- 1.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):-. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, Qaseem A; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians . Hypertension limbo: balancing benefits, harms, and patient preferences before we lower the bar on blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):369-370. doi: 10.7326/M17-3293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. ; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee . Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127. Accessed April 15, 2018. [PubMed]

- 5.Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense . VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in the primary care setting. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/htn/VADoDCPGHTN2014.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 6.National Heart Foundation of Australia . Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults: 2016. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/PRO-167_Hypertension-guideline-2016_WEB.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 7.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34(28):2159-2219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al. ; Hypertension Canada . Hypertension Canada’s 2018 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(5):506-525. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics . National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 state and national summary tables. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 11.DynaMed Plus . Hypertension: guidelines and resources. https://www.dynamed.com/condition/hypertension#Guidelines. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 12.UpToDate . Society guideline links: hypertension in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/society-guideline-links-hypertension-in-adults?topicRef=3852&source=see_link. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 13.DynaMed Plus . https://www.dynamed.com/. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 14.UpToDate . https://www.uptodate.com. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 15.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians and the Commission on Health of the Public and Science of the American Academy of Family Physicians . Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):430-437. doi: 10.7326/M16-1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackey TK, Liang BA. The role of practice guidelines in medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2011;13(1):36-41. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2011.13.1.hlaw1-1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71-72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, Ollenschläger G, Phillips S, van der Wees P; Board of Trustees of the Guidelines International Network . Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):525-531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwyn G, Cochran N, Pignone M. Shared decision making: the importance of diagnosing preferences. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1239-1240. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alston C, Berger ZD, Brownlee S, et al. ; National Academy of Medicine . Shared decision-making strategies for best care: patient decision aids. https://nam.edu/perspectives-2014-shared-decision-making-strategies-for-best-care-patient-decision-aids/. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 23.Spatz ES, Krumholz HM, Moulton BW. Prime time for shared decision making. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1309-1310. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt G. GRADE weak or conditional recommendations mandate shared decision-making: author response. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;102:147-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Excluded Clinical Practice Guidelines

eTable 2. Population-Intervention-Comparator Specifications of Reference Recommendations

eTable 3. Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines

eTable 4. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines

eTable 5. Consistency of Direction and Direction and Strength Across Clinical Practice Guidelines With Sensitivity Analysis for Excluding Insufficient Ratings

eTable 6. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding American College of Cardiology

eTable 7. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding American College of Physicians

eTable 8. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding European Society of Hypertension

eTable 9. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding Hypertension Canada

eTable 10. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding Eighth Joint National Committee

eTable 11. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding National Heart Foundation of Australia

eTable 12. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

eTable 13. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Excluding Department of Veterans Affairs

eTable 14. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Among High Importance Recommendations

eTable 15. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across Clinical Practice Guidelines Among Lower Importance Recommendations

eTable 16. Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources

eTable 17. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources

eTable 18. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding American College of Cardiology

eTable 19. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding American College of Physicians

eTable 20. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding DynaMed Plus

eTable 21. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding European Society of Hypertension

eTable 22. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding Hypertension Canada

eTable 23. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding Eighth Joint National Committee

eTable 24. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding National Heart Foundation of Australia

eTable 25. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

eTable 26. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding UpToDate

eTable 27. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings by Recommendation Across All Recommendation Sources Excluding Department of Veterans Affairs

eTable 28. Consistency of Direction and Strength Ratings Across All Recommendation Sources, With Sensitivity Analysis for Excluding Insufficient Ratings

eTable 29. Changes from the 2013 to the 2018 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension